Italian Consumers: Craft Beer or No Craft Beer, That Is the Question

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Model

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Theoretical Background

- The extended model of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [41,42]. Recently, many new constructs and theoretical approaches have been added to the TPB theory [43,44]. Among the studies on beverages, the articles by Sabina de Castillo et al. (2021) [45] and García-Barrón (2025) [46] stand out. The authors apply the extended model to the theory of planned behavior by adding other constructs to the original ones indicated by Ajzen, the first to predict the intention and behavior of local wine consumption [45], the second to determine the factors that influence the consumption of a traditional fermented beverage such as pulque to contribute to its promotion and to identify new marketing opportunities [46]. Ungureanu et al. in a very recent study on the agri-food sector in a north-eastern region of Romania, apply PLS-SEM to identify the elements that influence consumers’ purchasing decisions [47]. In their work, the authors consider sociocultural influences, product characteristics, brand trust, tradition, and lifestyle, examining the interrelationships between subjective norms, product attributes, price, consumer trust, and purchasing decisions. In this theoretical approach, in addition to the addition of new constructs, other theories were considered.

- Zhao et al. (2025), in their study on the beverage industry and sustainable marketing, use PLS-SEM, integrating the Big Five personality model (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) with the experiential marketing theory, building a chain mediation model that links personality traits, experiential dimensions and green purchase intention [50]. In their work, they consider the “Experiential Marketing Theory” (sense, sensation, thought, action and relationship) [51], with the “Trait Theory” of Tett et al. (2021) according to the latter, specific situational cues activate consumers’ personality traits, eliciting emotional and behavioral responses [52]. This theoretical integration offers insights into how intrinsic personality traits interact with experiential stimuli to shape green consumption experiences.

- The protection motivation theory (PMT), Pang et al., 2021 [53] in their study on factors influencing intention to purchase organic food, propose Roger’s (1975) protection motivation theory (PMT) [54]. PLS-SEM has also recently been used to explore the role of health-related perceptions in influencing citizens’ engagement in forest conservation using the health belief model (HBM) [55].

- Also very interesting for foods and beverages is the cognitive response theory (CRT), which examines the factors that influence the persuasion to consume a product. In the work of Goel and Garg, A., 2025, such exhortation is addressed to people by influencers and/or through promotional messages and information [56]. Due to the limitations of human influencers, companies are allocating budgets to promote marketing strategies based on virtual influencers (VIs), whose popularity is pushing companies to redesign their marketing strategies [56].

- Other studies focus on consumer acceptance of novel foods and beverages (NFBs). In this regard, Syuzanna Mosikyan et al., 2024 [57] in their systematic literature review, examine the main key theories and theoretical frameworks identified on consumer acceptance of novel foods and beverages (NFBs). They emphasize the importance of individual beliefs, attitudes, and subjective norms that shape consumer acceptance. This highlighted the importance of understanding the cognitive and psychological mechanisms underlying consumer decision-making processes and which influence when new foods and beverages (NFBs) are introduced into a market.

- Anchored in Consumer Culture Theory (CCT), this field of study examines how consumption is influenced by broader cultural and social contexts [14,18]. CCT emphasizes that consumption is not an isolated individual activity, but is profoundly influenced by the social and cultural context in which it occurs and represents an expression of identity and belonging to a group [58]. It represents a cultural practice that contributes to creating and maintaining shared meanings and values within a territory. Within the theory of consumer culture, craft beer represents an expression of identity, a lifestyle, and plays a role in social construction, identity expression, and meaning-making. In this regard, Sakdiyakorn and Chirakranont’s contribution to a case study of community craft beer consumption in Thailand is interesting [59]. Ulver et al. (2021) [60] in their work on the social ethics of craft consumption, also examine the case of craft beer in a regulated market. The authors question how an alcoholic beverage can have ethical meanings despite strong health trends in global consumer culture and find that craft beer is integrated with a consumerist imaginary of social work and community ethics, which overcomes the potential stigma of alcohol. Weber et al. (2018) [61] also explored consumer culture and behavior to test Wisconsin residents’ loyalty to local craft beer versus imported beer. The research showed not only the study participants’ ethnocentric tendencies, but also their cultural behavior as part of the system for these products in Wisconsin, USA [62].

- Agnieszka Wiśniewska et al., 2025, incorporate the Value-Believes-Norms theory (VBN) into their study on consumer engagement for a green economy [63]. This theory argues that individual values influence beliefs, personal norms, and behavior. In the context of local connection, VBN suggests that an individual’s core values regarding the protection of the local economy and food and beverage producers foster specific beliefs and concerns about socioeconomic and environmental issues, contributing to behavioral attitudes and actions that favor the local economy and environment.

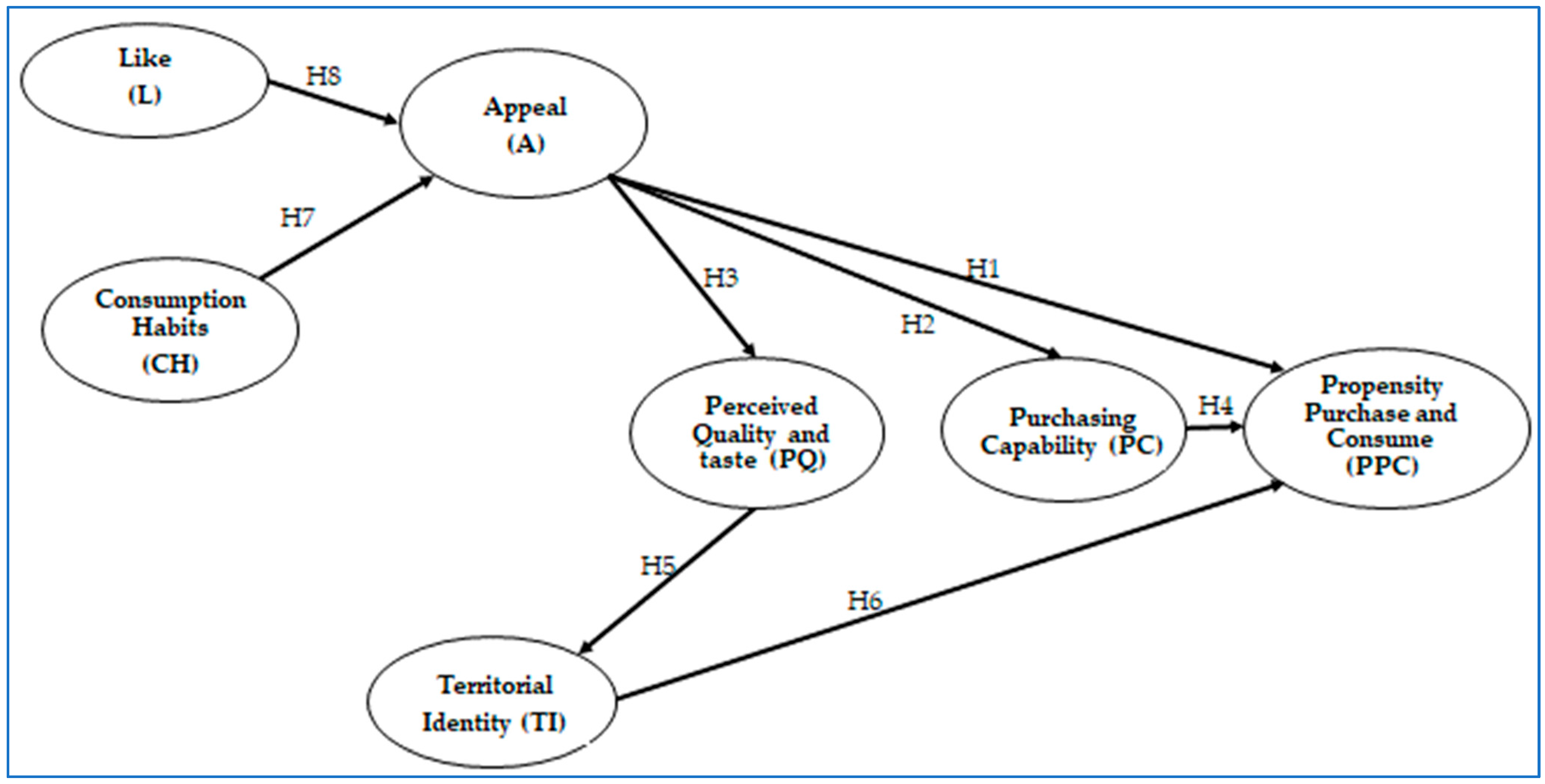

2.3. Hypothesis and Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

3.2. Data Collection and Survey Structure

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

4.2. Path Modeling Results, Validation, and Evaluation of PLS-SEM Applied to Craft Beer in Italy

- -

- H1, where Appeal exerts a marked and significant effect on the propensity to purchase and consume craft beer. In the final results, the total effect of the β coefficient increases from 0.658 to 0.702, as does the t-value, which increases from 13.284 to 18.573.

- -

- H5, where Perceived Quality exerts a marked and significant effect on Territorial Identity, β = 0.498 and t-value = 11.346, with no mediation effects.

- -

- H3, where Appeal exerts a significant effect on Perceived Quality (β = 0.497 and t-value = 11.316).

- -

- Paths H8 (β = 0.423 and t-value = 8.724) and H7 (β = 0.401 and t-value = 7.993), i.e., Like and Consumption Habits, are followed by the Appeal of Craft Beer.

- -

- Consumption habits lead to two valid and significant paths: one path leading to the propensity to consume and purchase craft beer, mediated by the Appeal construct (CH -> A -> PPC) (β = 0.282, t-value = 6.560); and another path leading, again mediated by the Appeal construct, to Perceived Quality (CH -> A -> PQ), where β = 0.200 and t-value = 6.182.

- -

- Finally, two paths are highlighted: the first, A -> PQ -> TI (β = 0.249 t-value = 6.152), where the appeal of craft beer is mediated by consumers’ emphasis on perceived quality; the second, L -> A -> PQ -> TI (β = 0.105 t-value = 5.057), in this case mediated by the Like construct, through the mediation of Appeal and Perceived Quality, highlights consumers’ appreciation for the territorial identity and local products.

- -

- The remaining paths, while valid and significant, appear less impactful, with t-values ranging from 4.531 to 2.165.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Hypothesis | β | SD | t-Value | p-Value | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||||

| A -> PPC | H1 | 0.044 | 0.016 | 2.666 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.077 |

| A -> TI | H3 -> H5 | 0.249 | 0.040 | 6.152 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.329 |

| CH -> PC | H7 -> H2 | 0.058 | 0.021 | 2.647 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.101 |

| CH -> PPC | H7 -> H1 | 0.282 | 0.042 | 6.560 | 0.000 | 0.202 | 0.366 |

| CH -> PQ | H7 -> H3 | 0.200 | 0.032 | 6.182 | 0.000 | 0.141 | 0.263 |

| CH -> TI | H7 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.100 | 0.021 | 4.531 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.145 |

| L -> PC | H8 -> H2 | 0.061 | 0.022 | 2.739 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.107 |

| L -> PPC | H8 -> H1 | 0.297 | 0.037 | 8.150 | 0.000 | 0.227 | 0.370 |

| L -> PQ | H8 -> H3 | 0.210 | 0.031 | 6.895 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.272 |

| L -> TI | H8 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.105 | 0.021 | 5.057 | 0.000 | 0.068 | 0.149 |

| PQ -> PPC | H5 -> H6 | 0.059 | 0.027 | 2.165 | 0.030 | 0.008 | 0.113 |

| Hypothesis | β | SD | t-Value | p-Value | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||||

| A -> PC -> PPC | H2 -> H4 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 2.104 | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.030 |

| A -> PQ -> TI | H3 -> H5 | 0.249 | 0.040 | 6.152 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.329 |

| CH -> A -> PQ -> TI -> PPC | H7 -> H3 -> H5 -> H6 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 1.990 | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.024 |

| PQ -> TI -> PPC | H5 -> H6 | 0.059 | 0.027 | 2.165 | 0.030 | 0.008 | 0.113 |

| CH -> A -> PC | H7 -> H2 | 0.058 | 0.021 | 2.647 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.101 |

| CH -> A -> PPC | H7 -> H1 | 0.264 | 0.042 | 6.106 | 0.000 | 0.185 | 0.351 |

| L -> A -> PC | H8 -> H2 | 0.061 | 0.022 | 2.739 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.107 |

| CH -> A -> PQ | H7 -> H3 | 0.200 | 0.032 | 6.182 | 0.000 | 0.141 | 0.263 |

| L -> A -> PPC | H8 -> H1 | 0.278 | 0.037 | 7.566 | 0.000 | 0.208 | 0.353 |

| L -> A -> PQ | H8 -> H3 | 0.210 | 0.031 | 6.895 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.272 |

| A -> PQ -> TI -> PPC | H3 -> H5 -> H6 | 0.029 | 0.014 | 2.060 | 0.039 | 0.004 | 0.059 |

| CH -> A -> PC -> PPC | H7 -> H2 -> H4 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.962 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.012 |

| CH -> A -> PQ -> TI | H7 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.100 | 0.021 | 4.531 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.145 |

| L -> A -> PC -> PPC | H8 -> H2 -> H4 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 2.065 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| L -> A -> PQ -> TI | H8 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.105 | 0.021 | 5.057 | 0.000 | 0.068 | 0.149 |

| L -> A -> PQ -> TI -> PPC | H8 -> H3 -> H5 -> H6 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 1.974 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.026 |

References

- Hornsey, I.S. Beer: History and Types. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 345–354. ISBN 978-0-12-384953-3. [Google Scholar]

- Meussdoerffer, F.G. A Comprehensive History of Beer Brewing. In Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, T. Beer and Brewing. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell, S.L. The Spatial Diffusion of Beer from Its Sumerian Origins to Today. In The Geography of Beer; Patterson, M., Hoalst-Pullen, N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 23–29. ISBN 978-94-007-7786-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey, I.S. A History of Beer and Brewing; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2003; Volume 34, ISBN 0-85404-630-5. [Google Scholar]

- Esposti, R.; Fastigi, M.; Viganò, E. Italian Craft Beer Revolution: Do Spatial Factors Matter? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastigi, M.; Viganò, E.; Esposti, R. The Italian Microbrewing Experience: Features and Perspectives. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2018, 7, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, A. Dieci Anni Di Cronache Di Birra: La Storia Di Un Decennio Di Birra Artigianale Italiana; Independently published 2018.

- Marceddu, R.; Carrubba, A.; Alfeo, V.; Alessi, A.; Sarno, M. Adapting American Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Varieties to Mediterranean Sustainable Agriculture: A Trellis Height Exploration. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, T.; Drago, M. La Birra Artigianale è Tutta Colpa Di Teo; Feltrinelli: Lombardy, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baiano, A. Craft Beer: An Overview. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2021, 20, 1829–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Associazione dei Birrai e dei Maltatori AssoBirra Annual Report 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.assobirra.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/AnnualReport-2024.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Szolnoki, G.; Nelgen, S.; Pensel, E.; Sperl, A. Craft Beer in the Land of the Purity Law—The German Beer Industry and the Purity Requirement in the Course of Time. In Case Studies in the Beer Sector; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 267–279. ISBN 978-0-12-817734-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rivaroli, S.; Lindenmeier, J.; Spadoni, R. Attitudes and Motivations Toward Craft Beer Consumption: An Explanatory Study in Two Different Countries. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronache di Birra. Whatabeer Italian Craft Beer Trend 2024. 2025. Available online: https://cdn1.cronachedibirra.it/wp-content/uploads/20250512122220/Italian-Craft-Beer-Trends-2024.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- OBIArt & Unionbirrai Birra Artigianale Filiere e Mercati Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.unionbirrai.it/admin/public/pagina_traduzione/c6292735b605b52c8f19f8f7b41a34a8/Report_UBOBIART_2022.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Pilone, V.; Di Pasquale, A.; Stasi, A. Consumer Preferences for Craft Beer by Means of Artificial Intelligence: Are Italian Producers Doing Well? Beverages 2023, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaroli, S.; Lindenmeier, J.; Spadoni, R. Is Craft Beer Consumption Genderless? Exploratory Evidence from Italy and Germany. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.B.; Minim, L.A.; Nascimento, M.; Ferreira, G.H.D.C.; Minim, V.P.R. Characterization of the Consumer Market and Motivations for the Consumption of Craft Beer. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Kordialik-Bogacka, E.; Maggi, L.; Lambri, M.; Sckokai, P. Consumer Interest in Specialty Beers in Three European Markets. Food Res. Int. 2016, 85, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, B.; Laureti, T.; Poponi, S.; Secondi, L. Beer Choice and Consumption Determinants When Craft Beers Are Tasted: An Exploratory Study of Consumer Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Corona, C.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Chollet, S.; Valentin, D. The Building Blocks of Drinking Experience across Men and Women: A Case Study with Craft and Industrial Beers. Appetite 2017, 116, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, A.; Quici, L. Craft Beer Mon Amour: An Exploration of Italian Craft Consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2671–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.S.; Bazzani, C.; Ha, K.A.; Nayga, R.M. Does the Origin of Inputs and Processing Matter? Evidence from Consumers’ Valuation for Craft Beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 89, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Kulieva, V.A.; Hernández-Martínez, E.; Minchán-Velayarce, H.H.; Pasapera-Campos, S.E.; Luque-Vilca, O.M. A Comprehensive Review of the Benefits of Drinking Craft Beer: Role of Phenolic Content in Health and Possible Potential of the Alcoholic Fraction. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cela, N.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Torri, L. Fruitful Brewing: Exploring Consumers’ and Producers’ Attitudes towards Beer Produced with Local Fruit and Agroindustrial By-Products. Foods 2024, 13, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Merlino, V.M.; Blanc, S.; Bargetto, A.; Borra, D. Latent Class Analysis and Individuals’ Preferences Mapping: The New Consumption Orientations and Perspectives for Craft Beer in North-West Italy. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, C.; Mussini, M. What Is Craft?—An Empirical Analysis of Consumer Preferences for Craft Beer in Italy. Mod. Econ. 2020, 11, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Measuring Consumers’ Preferences for Craft Beer Attributes through Best-Worst Scaling. Agric. Econ. 2020, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongwat, A.; Talawanich, S. What Makes People Attend a Craft Beer Event? Investigating Influential Factors Driving Attitude and Behavioral Intention. ABAC J. 2024, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T. Hypotheses for the Reasons behind Beer Consumer’s Willingness to Purchase Beer: An Expanded Theory from a Planned Behavior Perspective. Foods 2020, 9, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, R.; Guo, L.; Zhao, D.; Sun, B. Development and Validation of a Consumer-Oriented Sensory Evaluation Scale for Pale Lager Beer. Foods 2025, 14, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Corona, C.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; García, M.; Chollet, S.; Valentin, D. Craft vs. Industrial: Habits, Attitudes and Motivations towards Beer Consumption in Mexico. Appetite 2016, 96, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadini, G.; Bertuzzi, T.; Rossi, F.; Spigno, G.; Porretta, S. Uncovering Patterns of Italian Consumers’ Interest for Gluten-Free Beers. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2021, 79, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggah, E.M.; McSweeney, M.B. Females’ Attitude and Preference for Beer: A Conjoint Analysis Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, L.; Stanković, M.; Ruggeri, M.; Savastano, M. Craft Beer in Food Science: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Beverages 2024, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sánchez, A.; De La Cruz Del Río-Rama, M.; Álvarez-García, J.; Oliveira, C. Analysis of Worldwide Research on Craft Beer. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221108154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mora, Y.N.; Verde-Calvo, J.R.; Malpica-Sánchez, F.P.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B. Consumer Studies: Beyond Acceptability—A Case Study with Beer. Beverages 2022, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellano, F.; Rizzo, A.; Makkonen, T.; Anversa, I.G.; Cantafio, G. Exploring Senses of Place and Belonging in the Finnish, Italian and U.S. Craft Beer Industry: A Multiple Case Study. J. Cult. Geogr. 2023, 40, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ualema, N.J.M.; Dos Santos, L.N.; Bogusz, S.; Ferreira, N.R. From Conventional to Craft Beer: Perception, Source, and Production of Beer Color—A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer Attitudes and Behavior: The Theory of Planned Behavior Applied to Food Consumption Decisions. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 70, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.S.; Oliver, M.; Simnadis, T.; Beck, E.J.; Coltman, T.; Iverson, D.; Caputi, P.; Sharma, R. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and Dietary Patterns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, H.; Knappstein, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P.; Kabst, R. How Effective Are Behavior Change Interventions Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior? A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Z. Für Psychol. 2016, 224, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina Del Castillo, E.J.; Díaz Armas, R.J.; Gutiérrez Taño, D. An Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Local Wine Consumption Intention and Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Barrón, S.E.; Gonzalez-Hemon, G.; Herrera López, E.J.; Carmona-Escutia, R.P.; Leyva-Trinidad, D.A.; Gschaedler, A.C. Prediction of the Consumption of a Traditional Fermented Beverage via an Expanded Model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 2381–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, B.A.; Jităreanu, A.F.; Ungureanu, G.; Costuleanu, C.L.; Ignat, G.; Prigoreanu, I.; Leonte, E. Analysis of Food Purchasing Behavior and Sustainable Consumption in the North-East Region of Romania: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Zhang, J.; Paul, J.; Gilal, N.G. The Role of Self-Determination Theory in Marketing Science: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Research. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Magno, F. The Value of Self-Determination Theory in Marketing Studies: Insights from the Application of PLS-SEM and NCA to Anti-Food Waste Apps. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Hashim, N.M.H.N.; Kakuda, N.; Si, S. Crafting Global Green Consumption: The Role of Personality Traits and Experiential Marketing in the Beverage Industry. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2025, 33, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Toich, M.J.; Ozkum, S.B. Trait Activation Theory: A Review of the Literature and Applications to Five Lines of Personality Dynamics Research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2021, 8, 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.M.; Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C. Antecedents of Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Organic Food: Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Protection Motivation Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W.; Deckner, C.W. Effects of Fear Appeals and Physiological Arousal upon Emotion, Attitudes, and Cigarette Smoking. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 32, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleknia, R. Urban Forests and Public Health: Analyzing the Role of Citizen Perceptions in Their Conservation Intentions. City Environ. Interact. 2025, 26, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Garg, A. Virtual Personalities, Real Bonds: Anthropomorphised Virtual Influencers’ Impact on Trust and Engagement. J. Consum. Mark. 2025, 42, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosikyan, S.; Dolan, R.; Corsi, A.M.; Bastian, S. A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda to Study Consumer Acceptance of Novel Foods and Beverages. Appetite 2024, 203, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Thompson, C.J. Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdiyakorn, M.; Chirakranont, R. Brewing Social Capital: A Case Study of Thailand’s Craft Beer Consumption Community. J. Consum. Cult. 2024, 24, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulver, S.; Huntzinger, A.; Lindblom, K.; Olsson, E.B.; Paus, M. The Social Ethics of Craft Consumption. The Case of Craft Beer in a Regulated Market. In Case Studies in the Beer Sector; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 281–298. ISBN 978-0-12-817734-1. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.J.; Lambert, J.T.; Conrad, K.A.; Jennings, S.S.; Mastal Adams, J.R. Discovering a Cultural System Using Consumer Ethnocentrism Theory. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2018, 31, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Firbasová, Z. The Role of Consumer Ethnocentrism in Food Product Evaluation. Agribusiness 2003, 19, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, A.; Liczmańska-Kopcewicz, K.; Żemigała, M. Cognitive and Affective Antecedents of Consumer Engagement in Green Innovation Processes. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Corona, C.; Valentin, D.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Chollet, S. The Role of Gender and Product Consumption in the Mental Representation of Industrial and Craft Beers: An Exploratory Study with Mexican Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 60, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Worch, T.; Phelps, T.; Jin, D.; Cardello, A.V. Preference Segments among Declared Craft Beer Drinkers: Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Responses Underlying Craft-Style vs. Traditional-Style Flavor Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaroli, S.; Hingley, M.K.; Spadoni, R. The Motivation behind Drinking Craft Beer in Italian Brew Pubs: A Case Study. Econ. AGRO-Aliment. 2019, 20, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F.; Ringle, C.M. Guest Editorial: Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in Quality Management. TQM J. 2024, 36, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, W.; Selander, J. The Swedish Alcohol Monopoly: A Bottleneck for Microbrewers in Sweden? Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1953769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.F.; Ribeiro, A.P.L.; Vieira, K.C.; Pereira, R.C.; Carneiro, J.D.D.S. Specialty Beers Market: A Comparative Study of Producers and Consumers Behavior. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, G.; Tuccio, G.; Timpanaro, G. Analysis of Italian Craft Beer Consumers: Preferences and Purchasing Behaviour. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Skoglund, W.; Laven, D. Craft beer—Building social terroir through connecting people, place and business. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2020, 13, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, C. The Emergence of Italian Craft Breweries and the Development of Their Local Identity. In The Geography of Beer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, S.M.; Reese, J.F. Microbreweries as Tools of Local Identity. J. Cult. Geogr. 2003, 21, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, N. Heading down to the Local? Australian Rural Development and the Evolving Spatiality of the Craft Beer Sector. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Porretta, S. Uncovering Patterns of Consumers’ Interest for Beer: A Case Study with Craft Beers. Food Res. Int. 2017, 91, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleban, J.; Nickerson, I. To Brew, or Not to Brew-That Is the Question: An Analysis of Competitive Forces in the Craft Brew Industry. J. Int. Acad. Case Stud. 2012, 18, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Colton, D.; Covert, R.W. Designing and Constructing Instruments for Social Research and Evaluation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-7879-9808-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton, Mifflin and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; p. 623. ISBN 978-0-395-61556-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K.; Kwak, H.S. Influence of Functional Information on Consumer Liking and Consumer Perception Related to Health Claims for Blueberry Functional Beverages. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Terry, D.J.; Manstead, A.S.R.; Louis, W.R.; Kotterman, D.; Wolfs, J. The Attitude–Behavior Relationship in Consumer Conduct: The Role of Norms, Past Behavior, and Self-Identity. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 148, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-T.; Pham, T.-N. Consumer Attitudinal Dispositions: A Missing Link between Socio-Cultural Phenomenon and Purchase Intention of Foreign Products: An Empirical Research on Young Vietnamese Consumers. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1884345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.-T. Greenwash and Green Brand Equity: The Mediating Role of Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust, and the Moderating Role of Green Concern. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. ISBN 978-3-540-32825-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM Methods for Research in Social Sciences and Technology Forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Esposito, V.; Chatelin, Y.; Lauro, C. PLS Path Modelling’. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; ISBN 978-3-642-52514-8. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, S. PLS and Success Factor Studies in Marketing. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications in Marketing and Related Fields; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 409–425. ISBN 978-3-540-32825-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–56. ISBN 978-3-319-05542-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Use in Marketing Research in the Last Decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Becker, J.-M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEMs Most Wanted Guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 321–346. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, W.V.; Mouret, M.; Blackmore, S.; Pelquest-Hunt, T.; Urdapilleta, I. Representation of Complexity in Wine: Influence of Expertise. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cela, N.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Torri, L. Predicting Consumers’ Attitude towards and Willingness to Buy Beer Brewed with Agroindustrial by-Products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 126, 105414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, C.; Shelton, T.; Daly, G.; Hiner, C.C.; Hagelman, R.R. Assessing Neolocalism in Microbreweries. Pap. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 2, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, L.; Arru, B.; Camanzi, L.; Furesi, R.; Malorgio, G.; Pulina, P.; Madau, F.A. Factors Influencing Consumption Intention of Insect-Fed Fish among Italian Respondents. Foods 2023, 12, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, W. Microbreweries and Finance in the Rural North of Sweden—A Case Study of Funding and Bootstrapping in the Craft Beer Sector. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 9, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D.; Cameron, C.J. Network Sampling: From Snowball and Multiplicity to Respondent-Driven Sampling. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2017, 43, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewers, F.L.; Ferreira, G.R.; Arruda, H.F.D.; Silva, F.N.; Comin, C.H.; Amancio, D.R.; Costa, L.D.F. Principal Component Analysis: A Natural Approach to Data Exploration. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Wu, Q. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Practical Considerations. Educ. Meas. 2007, 26, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Kline, C. Rural Tourism and the Craft Beer Experience: Factors Influencing Brand Loyalty in Rural North Carolina, USA. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, M.I.; Motoki, K.; Spence, C.; Velasco, C. Factors Influencing the Choice of Beer: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollaro, M.; Fabbrizzi, S.; Sottini, V.A.; Fabbri, B.; Menghini, S. Linking Sustainability, Embeddedness and Marketing Strategies: A Study on the Craft Beer Sector in Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, R.N.; Rutigliano, C.A.C.; Rizzo, V.; Muratore, G. Exploring Beer Culture Dissemination and Quality Perception through Different Media: The Craft Beer Experience. Food Humanit. 2025, 4, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Sarstedt, M.; Fuchs, C.; Wilczynski, P.; Kaiser, S. Guidelines for Choosing between Multi-Item and Single-Item Scales for Construct Measurement: A Predictive Validity Perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.R.A.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.H.M. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker Criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Stol, K.-J. PLS-SEM for Software Engineering Research: An Introduction and Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to Perform and Report an Impactful Analysis Using Partial Least Squares: Guidelines for Confirmatory and Explanatory IS Research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Krey, N. Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and Recommendations. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schuberth, F.; Rademaker, M.E.; Henseler, J. Assessing the Overall Fit of Composite Models Estimated by Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 1678–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A Step-by-Step Guide to Get More out of Your Bootstrap Results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Koppius Predictive Analytics in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); ResearchGate: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Rönkkö, M. Statistical Inference with PLSC Using Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Singapore, 1997; ISBN 978-0-521-57391-7. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, A. The Beer’s Journey from Grain to the Table, from the View of the Economic and Food Safety of the Value Chain, through Indepth Interviews. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 17, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Juhl, H.J. Consumer Wants and Use of Ingredient and Nutrition Information for Alcoholic Drinks: A Cross-Cultural Study in Six EU Countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, A.J. Consumer Perceptions of Nutrition Labeling on Alcoholic Beverages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 133, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Survey Question | Main Reference Literature |

|---|---|---|

| PPC | PPC_1 For me, craft beer tastes better than industrial beer PPC_2 For me, craft beer is very good. PPC_3 Buying craft beer is my preference. | [17,29,64] |

| PC | PC_1 The availability and possibility of purchasing craft beer influences my choices | [17,19,23,24,29,33,70,71] |

| A | A_1 I’m interested and attracted by the craft beer phenomenon. A_2 Buying and consuming craft beer is in line with my lifestyle. A_3 I buy and consume craft beer because I’m interested in new alternatives and new flavors. | [14,21,24,57,64,69,97] |

| PQ | PQ_1 When I buy and consume craft beer, I consider the label. PQ_2 When I buy and/or consume craft beer, I pay close attention to safety and quality. PQ_3 When I buy and consume craft beer, I pay close attention to safety and quality. | [19,24,27,29,33,53,70] |

| TI | TI_1 I like to buy and/or drink craft beer to pair with food. TI_2 I prefer to buy and drink craft beer from my local area. TI_3 I buy and drink craft beer because I want to support local breweries. | [21,45,75,76,77,79,98,99,100,101] |

| CH | CH_1 I usually drink craft beer when I’m away from home CH_2 I like to drink craft beer at home CH_3 When I drink craft beer, I choose the type CH_4 I drink craft beer because it satisfies me | [19,33,69,76] |

| L | L_1 I follow craft beer influencers L_2 I have a positive attitude toward local craft beers and/or beers from other areas and countries | [21,45,74,77] |

| Indication | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age class | 18–29 | 64 | 17.6 |

| 30–39 | 97 | 26.7 | |

| 40–49 | 113 | 31.1 | |

| 50 or older | 89 | 24.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 234 | 64.5 |

| Female | 129 | 35.5 | |

| Education | primary schools | 11 | 3.0 |

| High School | 146 | 40.2 | |

| 3 year university | 59 | 16.3 | |

| Master’s degree | 102 | 28.1 | |

| post degree | 45 | 12.4 | |

| Income | not answer/no income | 27 | 7.4 |

| Up to 15,000 €/year | 66 | 18.2 | |

| 15,000–29,000 €/year | 157 | 43.3 | |

| 30,000–50,000 €/year | 86 | 23.7 | |

| 50,000 €/year or more | 27 | 7.4 | |

| Working status | Employed | 281 | 77.4 |

| Student | 36 | 9.9 | |

| Retired | 22 | 6.1 | |

| Other | 24 | 6.7 | |

| No. of family members | I live alone | 52 | 14.3 |

| 2 members | 107 | 29.5 | |

| 3 members | 80 | 22.0 | |

| 4 members | 102 | 28.1 | |

| 5 or more members | 22 | 6.1 |

| n. | % | n. | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - I drink craft beer more often | 187 | 51.5 | - I drink industrial beer more often | 105 | 28.9 |

| Craft beer consumption | Industrial beer consumption | ||||

| - Never | 22 | 6.1 | - Never | 83 | 22.9 |

| - On some occasions | 159 | 43.8 | - On some occasions | 177 | 48.8 |

| - Once a week | 50 | 13.8 | - Once a week | 58 | 16.0 |

| - 2–3 times a week | 66 | 18.2 | - 2–3 times a week | 28 | 7.7 |

| - More than 2–3 times a week | 66 | 18.2 | - More than 2–3 times a week | 17 | 4.7 |

| Do you prefer blonde, red, dark, or white beers? | Preferred alcohol content of the beers consumed | ||||

| - Golden ale | 140 | 38.6 | - Low alcohol content (less than 5°) | 66 | 18.2 |

| - Red ale | 40 | 11.0 | - 5° | 73 | 20.1 |

| - Stout | 36 | 9.9 | - 6–7° | 53 | 14.6 |

| - White | 11 | 3.0 | - Over 7° | 16 | 4.4 |

| - Indifferent | 136 | 37.5 | - I choose based on the type of beer | 155 | 42.7 |

| Where do you buy beer? (both industrial and craft) | Monthly expenditure declared for the purchase of beer (industrial and/or craft) | ||||

| - Beer shop only or in combination with other outlets (supermarket and liquor store) | 79 | 21.8 | - Around 20 euros | 128 | 35.3 |

| - Online only or in combination with other outlets (beer shop, supermarket, and retailer) | 81 | 22.3 | - Between 20 and 40 | 101 | 27.8 |

| - Supermarket only | 144 | 39.7 | - Between 41 and 60 | 49 | 13.5 |

| - Retailer only or in combination with supermarket | 30 | 8.3 | - Between 61 and 80 euros | 29 | 8.0 |

| - Liquor store only or in combination with another unspecified outlet | 29 | 8.0 | - More than 80 euros | 56 | 15.4 |

| Measurement | Constructs and Items | Standardized Variable Loadings | Kaiser–Meyer-Olkin KMO | Mean | Std. Deviation | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective | Appeal (A) | ||||||

| A_1 | I drink craft beer because I’m interested and attracted by the craft beer phenomenon. | 0.847 | 0.911 | 2.826 | 1.492 | 2.098 | |

| A_2 | Drinking craft beer is in line with my lifestyle. | 0.906 | 0.930 | 2.972 | 1.431 | 2.483 | |

| A_3 | When I drink craft beer, I like to experiment with new flavors. | 0.825 | 0.936 | 3.672 | 1.249 | 1.600 | |

| Reflective | Purchasing Capability (PC) | ||||||

| PC | My income and the price of craft beer influence my choices. | 1.000 | 0.785 | 3.063 | 1.009 | 1.000 | |

| Reflective | Propensity to Purchase and Consume (PPC) | ||||||

| PPC_1 | For me, craft beer tastes better than industrial beer. | 0.874 | 0.942 | 3.152 | 1.413 | 2.081 | |

| PPC_2 | For me, craft beer is very good. | 0.895 | 0.931 | 3.835 | 1.317 | 1.974 | |

| PPC_3 | Buying craft beer is a habit of mine. | 0.822 | 0.938 | 3.934 | 1.111 | 1.779 | |

| Reflective | Perceived Quality and Taste (PQ) | ||||||

| PQ_1 | When I buy and consume craft beer, I consider the label. | 0.800 | 0.856 | 3.179 | 1.400 | 1.618 | |

| PQ_2 | When I buy and consume craft beer, I pay close attention to quality and taste. | 0.904 | 0.888 | 3.554 | 1.215 | 1.957 | |

| PQ_3 | I’m interested in learning about craft beer production technology. | 0.809 | 0.881 | 3.132 | 1.283 | 1.599 | |

| Reflective | Territorial Identity (TI) | ||||||

| TI_1 | I enjoy purchasing and/or consuming craft beer to pair with food. | 0.817 | 0.940 | 2.983 | 1.273 | 1.429 | |

| TI_2 | I prefer purchasing and consuming local craft beer. | 0.741 | 0.871 | 3.011 | 1.251 | 1.462 | |

| TI_3 | I purchase and consume craft beer because I want to support local breweries. | 0.873 | 0.926 | 3.146 | 1.321 | 1.694 | |

| Formative | Consumption Habits (CH) | ||||||

| CH_1 | I usually drink craft beer when I’m away from home. | 0.736 | 0.926 | 2.559 | 1.103 | 1.940 | |

| CH_2 | I like to drink craft beer at home. | 0.710 | 0.927 | 2.592 | 1.057 | 1.920 | |

| CH_3 | When I drink craft beer, I choose the type. | 0.822 | 0.940 | 3.780 | 1.227 | 1.245 | |

| CH_4 | I drink craft beer because it satisfies me. | 0.789 | 0.889 | 2.986 | 1.261 | 2.896 | |

| Formative | Like (L) | ||||||

| L_1 | I follow craft beer influencers | 0.864 | 0.931 | 3.317 | 1.280 | 1.092 | |

| L_2 | I have a positive attitude toward craft beers, both local and from other areas and countries. | 0.734 | 0.972 | 2.163 | 1.298 | 1.092 | |

| Indication | A | PQ | PPC | PC | TI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct reliability and validity | |||||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.823 | 0.790 | 0.832 | 0.745 | |

| Composite Reliability (rho_a) | 0.828 | 0.827 | 0.859 | 0.775 | |

| Composite Reliability (rho_c) | 0.895 | 0.876 | 0.898 | 0.853 | |

| Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | 0.739 | 0.703 | 0.747 | 0.660 | |

| Discriminant validity—Heterotrait—Monotrait HTMT | |||||

| Appeal (A) | |||||

| Perceived Quality_ (PQ) | 0.600 | ||||

| Propensity of Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.892 | 0.503 | |||

| Purchasing Capability (PC) | 0.156 | 0.037 | 0.229 | ||

| Territorial Identity (TI) | 0.868 | 0.619 | 0.711 | 0.139 | |

| R2 | Q2 Predict * | |

|---|---|---|

| Appeal (A) | 0.561 | 0.550 |

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | 0.245 | 0.198 |

| Propensity Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.587 | 0.588 |

| Purchasing and Consumption (PC) | 0.021 | 0.039 |

| Territorial Identity (TI) | 0.246 | 0.170 |

| f2 | VIF | |

|---|---|---|

| Appeal (A) -> Perceived Quality and Taste (PQ) | 0.324 | 1.000 |

| Appeal (A) -> Propensity to Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.531 | 1.975 |

| Appeal (A) -> Purchasing Capability (PC) | 0.021 | 1.000 |

| Consumption Habits (CH) -> Appeal (A) | 0.196 | 1.807 |

| Like (L) -> Appeal (A) | 0.229 | 1.807 |

| Perceived Quality and Taste (PQ) -> Territorial Identity (TI) | 0.326 | 1.000 |

| Purchasing Capability (PC) -> Propensity to Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.024 | 1.023 |

| Territorial Identity (TI) -> Propensity to Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.017 | 1.969 |

| A | CH | L | PQ | PPC | PC | TI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appeal (A) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Consumption Habits (CH) | 0.679 | 1.000 | |||||

| Like (L) | 0.689 | 0.668 | 1.000 | ||||

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | 0.495 | 0.439 | 0.402 | 1.000 | |||

| Propensity to Purchase and Consume (PPC) | 0.755 | 0.826 | 0.687 | 0.429 | 1.000 | ||

| Purchasing Capability (PC) | 0.144 | 0.260 | 0.192 | 0.037 | 0.211 | 1.000 | |

| Territorial Identity (TI) | 0.701 | 0.501 | 0.527 | 0.496 | 0.592 | 0.134 | 1.000 |

| Path Coefficients | Hypothesis | β | Stdev. | t-Values | p-Values | 97.5% Confidence Intervals | Are the Hypotheses Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A -> PPC | H1 | 0.658 | 0.050 | 13.284 | 0.000 | [0.559; 0.753] | YES |

| A -> PC | H2 | 0.145 | 0.049 | 2.922 | 0.003 | [0.045; 0.236] | YES |

| A -> PQ | H3 | 0.497 | 0.044 | 11.316 | 0.000 | [0.403; 0.575] | YES |

| PC -> PPC | H4 | 0.101 | 0.033 | 3.061 | 0.002 | [0.036; 0.166] | YES |

| PQ -> TI | H5 | 0.498 | 0.044 | 11.346 | 0.000 | [0.399; 0.574] | YES |

| TI -> PPC | H6 | 0.118 | 0.052 | 2.275 | 0.023 | [0.015; 0.216] | YES |

| CH -> A | H7 | 0.401 | 0.049 | 7.993 | 0.000 | [0.290; 0.484] | YES |

| L -> A | H8 | 0.423 | 0.049 | 8.724 | 0.000 | [0.332; 0.522] | YES |

| Total Effects | Hypothesis | β | Stdev. | t-Values | p-Values * | 97.5% Confidence Intervals | Are the Hypotheses Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A -> PC | H2 | 0.145 | 0.049 | 2.922 | 0.003 | [0.048; 0.239] | YES |

| A -> PPC | H1 | 0.702 | 0.038 | 18.573 | 0.000 | [0.627; 0.776] | YES |

| A -> PQ | H3 | 0.497 | 0.044 | 11.316 | 0.000 | [0.410; 0.580] | YES |

| A -> TI | H3 -> H5 | 0.249 | 0.040 | 6.152 | 0.000 | [0.172; 0.329] | YES |

| CH -> A | H7 | 0.401 | 0.049 | 7.993 | 0.000 | [0.304; 0.497] | YES |

| CH -> PC | H7 -> H2 | 0.058 | 0.021 | 2.647 | 0.008 | [0.019; 0.101] | YES |

| CH -> PPC | H7 -> H1 | 0.282 | 0.042 | 6.560 | 0.000 | [0.202; 0.366] | YES |

| CH -> PQ | H7 -> H3 | 0.200 | 0.032 | 6.182 | 0.000 | [0.141; 0.263] | YES |

| CH -> TI | H7 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.100 | 0.021 | 4.531 | 0.000 | [0.062; 0.145] | YES |

| L -> A | H8 | 0.423 | 0.049 | 8.724 | 0.000 | [0.326; 0.517] | YES |

| L -> PC | H8 -> H2 | 0.061 | 0.022 | 2.739 | 0.006 | [0.020; 0.107] | YES |

| L -> PPC | H8 -> H1 | 0.297 | 0.037 | 8.150 | 0.000 | [0.227; 0.370] | YES |

| L -> PQ | H8 -> H3 | 0.210 | 0.031 | 6.895 | 0.000 | [0.153; 0.272] | YES |

| L -> TI | H8 -> H3 -> H5 | 0.105 | 0.021 | 5.057 | 0.000 | [0.068; 0.149] | YES |

| PC -> PPC | H4 | 0.101 | 0.033 | 3.061 | 0.002 | [0.037; 0.167] | YES |

| PQ -> PPC | H5 -> H6 | 0.059 | 0.027 | 2.165 | 0.030 | [0.008; 0.113] | YES |

| PQ -> TI | H5 | 0.498 | 0.044 | 11.346 | 0.000 | [0.408; 0.581] | YES |

| TI -> PPC | H6 | 0.118 | 0.052 | 2.275 | 0.023 | [0.016; 0.218] | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicolosi, A.; Di Gregorio, D.; Laganà, V.R.; Marcianò, C. Italian Consumers: Craft Beer or No Craft Beer, That Is the Question. Beverages 2025, 11, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060157

Nicolosi A, Di Gregorio D, Laganà VR, Marcianò C. Italian Consumers: Craft Beer or No Craft Beer, That Is the Question. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060157

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicolosi, Agata, Donatella Di Gregorio, Valentina Rosa Laganà, and Claudio Marcianò. 2025. "Italian Consumers: Craft Beer or No Craft Beer, That Is the Question" Beverages 11, no. 6: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060157

APA StyleNicolosi, A., Di Gregorio, D., Laganà, V. R., & Marcianò, C. (2025). Italian Consumers: Craft Beer or No Craft Beer, That Is the Question. Beverages, 11(6), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060157