Abstract

The beverage industry is undergoing a dynamic transition in terms of how and where consumers buy products. In an era of rapid digitalization and shifting consumer behaviors, this study investigates how Germany’s wine producers reach consumers and how the distribution landscape of German wine has transformed. A survey of more than 1000 German wine producers allowed us to explore multichannel strategies. Home-country distribution stands for 84% of the production, while export represents 16% of sales. Indirect sales via food retail safeguard a large portion of distribution, but direct sales to consumers matter in value-driven sales. The findings confirm the continued dominance of indirect retail, particularly food retail, while also highlighting a rebound in direct-to-consumer sales, value market approaches, and on-premises distribution. The results of this study contribute to closing data gaps by underlining that gastronomy has been re-established as a relevant distribution channel and that German wine has not profited from global growth in wine trading. Multichannel strategies are increasingly common, but they vary significantly in their depth and reach depending on different business models. We conducted a cluster analysis and identified three strategic groups: (1) consumer-centric, predominantly direct-to-consumer-oriented estates (63%); (2) industrial, multichannel producers with a strong presence in food retail and export (8%); and (3) hybrid operators balancing value and volume strategies (29%). This study contributes to the development of a more nuanced understanding of multichannel distribution in the wine sector and provides empirical insights into the strategic implications of firm heterogeneity.

1. Introduction

In an increasingly complex and competitive business environment, the formulation of an effective sales strategy and the design of an appropriate distribution system are critical value levers [1,2,3]. A sales strategy constitutes a fundamental element for the positioning of products or services, the identification and engagement of target markets, and subsequent revenue generation [4]. In the absence of a coherent and market-aligned strategy, even superior products may fail to fulfill their commercial potential [5].

Distribution systems, particularly those relying on multichannel sales, have gained prominence as firms seek to expand their market reach and enhance customer accessibility [6]. Multichannel distribution, which integrates direct sales, retail partnerships, e-commerce platforms, and third-party intermediaries, allows companies to address diverse consumer preferences and purchasing behaviors [7,8,9,10]. This approach can significantly increase market coverage, improve convenience for customers, and contribute to revenue diversification [11]. However, the implementation of a multichannel distribution strategy faces a range of managerial and operational challenges. These include ensuring consistency in pricing and brand messaging across channels, dealing with high costs, coordinating inventory and logistics, and mitigating channel conflict [12,13]. Moreover, the complexity of overseeing multiple distribution pathways often demands advanced technological infrastructure and increases costs [14]. Despite these challenges, multichannel distribution remains a strategically valuable approach when effectively managed [15]. Market access and potential market exploitation via superior sales and distribution strategies are contingent on industry characteristics, especially the nature of products and market structures [16].

The wine sector has undergone major transformations over the past two decades [17]. Changes in global consumption, increased competition, and the emergence of new producing as well as consuming regions have reshaped wine markets [18,19,20]. Reaching consumers is key in order to successfully compete in dynamic markets that are characterized by oversupply [21,22]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted supply chains [23,24]. Wine is supplied either for home consumption (off-premises), in which case the wine is bought from the producer (e.g., wine shop, online sales) or indirectly from intermediaries (e.g., food retail, special wine shops, e-business platforms), or via on-premises consumption (e.g., restaurants, events) [25,26]. Although home consumption dominates, on-premises wine consumption is of relevance not only for wine producers but also for the channel partners involved; the bottom line is that restaurants profit substantially from the sale of beverages, especially wine. In restaurants, wines are offered for an amount that is several times the buying price [27,28], and wine can represent one third of the restaurant bill [29]. Wine estates need to adjust their strategies and marketing efforts in order to adapt to the changing market environment, but they lack the transparency and data required to effectively steer their sales [30]. Distribution strategies for wine are shaped by institutional conditions and the maturity of the market environment, which vary significantly between established and emerging wine regions [31]. Despite the substantial academic literature on distribution systems and the transformation of global wine markets, there remains a considerable lack of knowledge concerning how wine producers, particularly across different business models, strategically sell and distribute their products. While the importance of sales and distribution strategies is well documented in the management literature [32], the producer perspective remains underrepresented in empirical research on the wine sector, especially with regard to structurally fragmented and regionally distinct markets such as Germany’s. This research thereby relied on theoretical work on the resource dependency of small businesses [33,34], dynamic capabilities [35,36] to adapt to changing environments, and strategic grouping to safeguard the fit of the business model to market needs [37] by exploring the constituencies of distribution strategies.

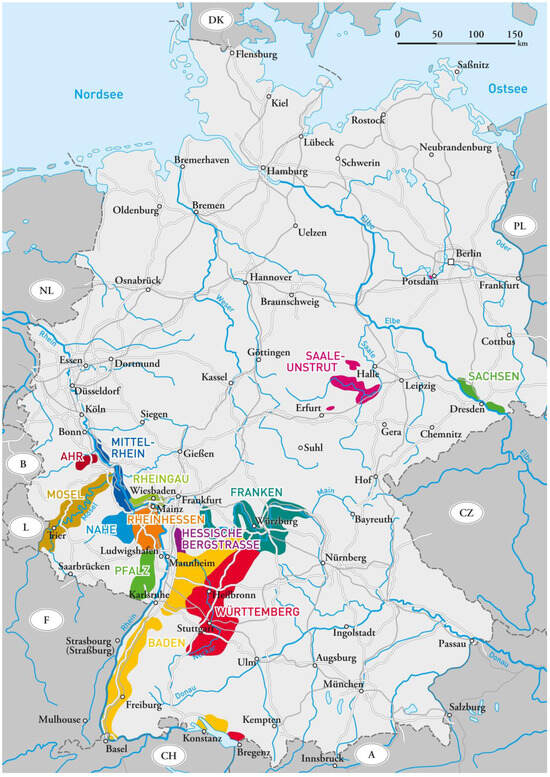

Having maintained stable per capita wine consumption of around 22 L for decades, the German wine market is mature, but it has recently suffered from a diminishing demand [38]. Despite national German wine production reaching a significant volume of about eight to ten million hectoliters annually, stemming from 13 designated wine regions (Appendix A Figure A1), international wines constitute more than 50% of the total annual wine consumption of about two billion liters. Indeed, Germany is the largest wine importer in the world [22]. Official statistics are available regarding the overall (German and international wines) supply of wine for home consumption in Germany (retail scanning data complemented by the results of a questionnaire on wine buying behavior distributed to selected households). According to these data, the majority of wine is purchased through food retail, with discounters holding a significant share of wine sales. These indirect channels meet consumer demands for convenience and low prices and offer variety. Specialty wine shops, which were originally brick-and-mortar sales outlets supplying wine predominantly in metropolitan areas and outside wine-producing regions, face competition from premiumized retail or discount offerings, as well as from online wine channels. In addition, in response to the demand for convenience, wine for home consumption can be bought online, supplied by wine producers, online retail platforms (e.g., Amazon), or special online wine retailers (e.g., Wine in Black, Geile Weine) [39]. Direct-to-consumer (DTC) wine sales have a strong tradition in Germany and allow wine producers to address niche segments, foster regional identity, and enable experiential buying [40,41]. Available market reports lack relevant information—for example, on-premises wine sales. Often, the stated market characteristics and evolution of the wine market in these reports (e.g., the prevalence of indirect sales, gains in online provision, the death of special retail, diminishing direct sales, the diminishing relevance of on-premises wine distribution, and the promising future of online wine sales) do not seem to be supported by reliable data. Furthermore, these market reports do not provide transparency from the producer’s perspective. This motivated us to investigate the distribution strategies of German wine producers from a supplier perspective, in order to provide information to address the lack of knowledge about channel strategies among wine producers and to construct a typology of strategies. While the growing adoption of multichannel approaches is widely acknowledged, data on specific channel combinations and interrelationships, such as the interplay of direct sales, specialist retail, gastronomy, online platforms, and food retail, remain scarce. This lack of data and transparency limits our understanding of strategic positioning, especially in a market where consumer preferences are becoming increasingly fragmented and distribution options are diversifying [42,43]. Larger producers are expected to supply retail and export, and smaller producers are expected to be more direct-to-consumer-centric. Although earlier segmentation studies have hinted at these patterns [44], systematic and current data confirming or challenging these assumptions could not be identified. Moreover, an omnichannel perspective, with knowledge of the number and combinations of distribution channels, helps managerial decisions in considering resource allocations, competencies, and profit impacts. Resource dependency is of relevance in an industry that is characterized by the dominance of micro or small businesses, such as the examined German wine industry [45,46,47]. Another gap in the literature concerns the misalignment between producers’ distribution strategies and actual consumer purchasing behavior. There is empirical evidence that market reports for home consumption are inaccurate, as they differ from consumer survey results on wine provisioning [48]. Although digital platforms and e-commerce are increasing in importance, there is a paucity of empirical insight into digital readiness, perceived barriers, and actual adoption patterns among wine estates [49].

By enhancing the empirical basis regarding market supply and strategic diversity in the wine industry’s distribution landscape, this study offers practical implications for producers, policymakers, and intermediaries.

2. Materials and Methods

Drawing on reports in the literature indicating that (a) industry characteristics drive channel strategies [50] and (b) dynamic environmental changes—such as structural changes and shifting consumer expectations in the wine industry—determine channel strategies and trigger supply transformation [51], we were motivated to invite wine producers across Germany to provide us with their distribution data. Our primary objectives were to quantify the actual distribution structures and to explore channel strategies. We developed a structured, quantitative online survey intended to target a representative range of wine estates in terms of size, production model, and regional affiliation. A call for participation in the survey was communicated via national and regional winegrowers’ associations, professional newsletters, and stakeholder mailing lists to maximize outreach and encourage participation. This gathering of participants aimed to reduce selection bias and ensure the inclusion of producers differing in size, regional affiliation, and business model. The survey participants were informed about the scientific purpose and confidentiality of the data-gathering process and were offered access to more detailed information on ethical data usage.

The resulting participation of 1053 producers across all thirteen German wine-growing regions (Appendix A Figure A1), responsible for more than half of Germany’s total wine production, underlines producers’ interest in the subject matter and the high degree of representativeness of our data. The surveyed population produced 646 million bottles (more than 500 million liters) of wine in 2023, therefore representing about 60% of the German wine production [38,52,53].

The aim of the empirical data generation process was to provide empirical insights into supply structures and the adaptation of German wine producers in their search for future-proof distribution models in an evolving market landscape. Indeed, existing channel data needed to be validated, and the lack of data on German wine distribution (e.g., on-premises distribution) needed to be addressed. Valid data and transparency enable producers to adapt their channel strategies in the face of a market that is diminishing in size. Three research questions guided our study:

- How is German wine distributed?

- What channel strategies can be observed?

- How has the supply and distribution of German wine changed?

Descriptive variables (producer type, size, and region) were gathered to facilitate structural analyses and strategic assessments [54]. In addition, our analysis went beyond an assessment of the current state of the wine market, and we compared the retrieved data with historic statistical information to generate time series in order to explore claims of a transition in wine supply and demand [55,56].

Germany’s wine sector is characterized by a large number of small- and medium-sized enterprises with heterogeneous structures and various business models for value creation. The questionnaire captured the production and sales volumes of various distribution channels. In the German wine industry, wine is sold predominantly in 0.75 or 1 L bottles; nevertheless, packaging formats (e.g., bag-in-box with higher container volume) were assessed. The variable “channel sales” evaluated distribution via direct-to-consumer (DTC), specialist retail, food retail, discount retail, e-business (indirect sales), on-premises (gastronomy), and export channels. The channel survey assessed sales and distribution for 2023.

Producers were classified into three categories according to their annual bottling volumes:

- Small-sized producers (<250,000 bottles/year);

- Medium-sized producers (250,000–1,000,000 bottles/year);

- Large-scale producers (>1,000,000 bottles/year).

German wine producers vary in their business models—for example, in their value creation processes: wine estates primarily produce and market wines from their own vineyards, allowing for tight control over quality and branding; cellars purchase grapes, must, or wine from external sources and operate larger-scale production facilities; and cooperatives, by contrast, process grapes from member growers collectively, benefitting from scale effects and marketing the wines of their members with common brands [57,58].

Cross-referencing was conducted on the basis of not only publicly available consumer-side data from the German Wine Institute but also the market data reports of market research agencies (e.g., Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (GfK); Nielsen/IQ), sold to interested parties in the industry. We employed accessible reports from the last 25 years. In addition, published market research and our own prior survey on strategic sales were used for validation. This dual perspective allowed for a comparison of supply-side sales with actual purchasing patterns on the consumer side. Furthermore, the reports were employed for a longitudinal data comparison.

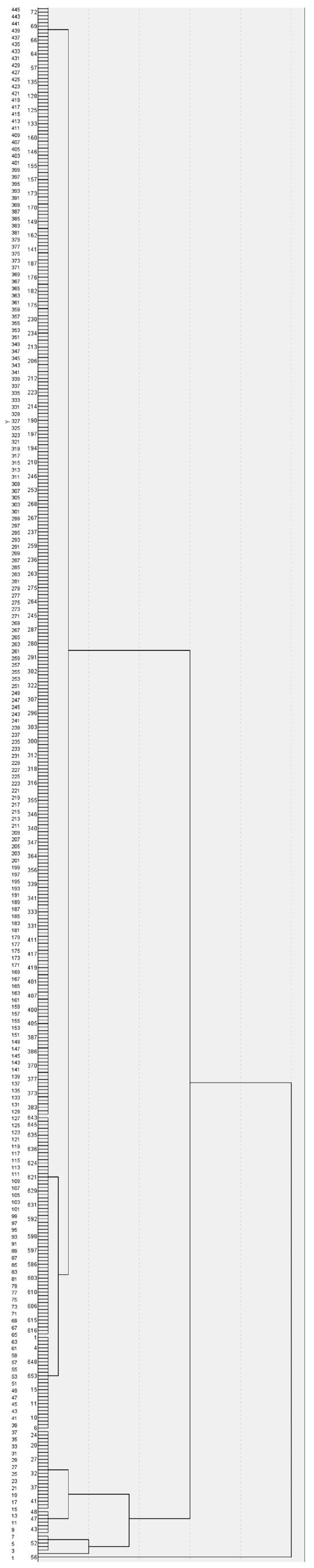

Statistical analysis was applied to assess producer-side channel relevance, complemented by comparative evaluations across winery sizes and regional affiliations. The data were cleaned to remove missing values and outliers, which improved the accuracy of the analysis. A cluster-analytical approach was applied using SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0.1.1). This approach aimed to reveal structurally distinct groups of producers based on their reported distribution channel configurations. In the first step, a hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted using Ward’s method and the squared Euclidean distance, a combination known for generating compact and interpretable clusters by minimizing within-group variance [59]. A dendrogram allowed us to visually assess clustering distances and determine an appropriate number of clusters for further analysis. To support data accuracy and reduce potential multicollinearity among the seven distribution variables (sales shares by channel), a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. PCA is commonly used in multivariate analysis to summarize interrelated variables and verify the dimensional structure underlying the clustering solution [60]. In the second step, a k-means cluster analysis was applied to assign each case to a cluster based on the results of the hierarchical procedure. This iterative partitioning method allows for the fine-tuning of group membership and increases the internal homogeneity within clusters [61]. Cluster centroids from the hierarchical analysis were used to initialize the k-means algorithm, thereby improving the convergence and interpretability. The final cluster solution yielded three distinct producer segments, each characterized by specific combinations of distribution channel usage. These empirically derived clusters formed the basis of the typology presented in Section 3 and enabled a structured interpretation of the strategic distribution profiles in the German wine sector.

The methodology was tailored to the research questions with the aim of developing strategic recommendations for producers, policymakers, and market actors interested in enhancing sustainability, market access, and consumer alignment in the German wine sector.

3. Results

3.1. Producer Landscape and Production

The survey population was dominated by small wine producers and by wine estates, in accordance with the German wine producer landscape [53]. More than four fifths of the participants were classified as small-sized, 8% as medium-sized, and 9% as large-scale producers. Likewise, the population consisted of 89% wine estates, 8% cooperatives, and 3% cellars. These three business models differ in terms of production, with wine estates producing an average of only 110,000 bottles annually, cooperatives 3.5 million, and cellars 14 million. Table 1 provides information about the population and underlines that a mix of business models and sizes were identified, but no cooperatives were classified as small-sized. A chi-squared test of independence revealed a statistically significant association between the business size and business type: χ2(4, N = 655) = 437.43, p < 0.001. To assess the strength of this association, Cramér’s V was calculated, resulting in a value of 0.578 (p < 0.001). According to common interpretation guidelines, this indicates a strong effect size, suggesting that business type distributions differ systematically across size categories.

Table 1.

Survey population overview: distribution of sizes and business models.

The data reveal the predominance of a small-scale producer structure across most German wine regions, with a few exceptions in regions where large-scale operations, primarily cooperatives and commercial cellars, play a more significant role (see Table 2). Producers from the three largest wine-growing regions in Germany (Rheinhessen, Pfalz, and Baden) accounted for 75% of the survey population, reflecting their combined share of nearly two thirds of the national vineyard area. For three wine regions (Ahr, Nahe, and Franken), the number of participants was insufficient to allow for their inclusion in the comparative regional analyses. The survey population illustrates specific regional wine production structures: Württemberg, Hessische Bergstrasse, and Baden stand out as above-average producer entities with high cooperative penetration, accounting for more than 70% of cooperative production; meanwhile, small-scale producers account for the vast majority, namely more than 65%, in most regions, underlining the fragmentation of the German wine production landscape. A chi-squared test confirmed the significant association between the wine-growing region and business size: χ2 = 118.87, p < 0.001. Cramér’s V = 0.301 (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Survey population—producer size class by wine region.

The data reveal that 0.75 L bottles dominate wine production, but one fourth of wines are packaged in one-liter bottles and 2% are distributed in other formats (e.g., bag-in-box). All size classes are characterized by a mix of packaging types, with the reliance of large entities on one-liter bottles, representing one third of production on average.

3.2. Distribution of German Wine

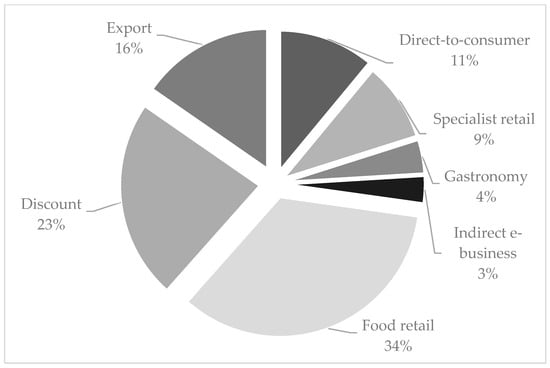

The survey results confirm the expected dominance of the national supply by German wine producers, representing 84% of German wine sales and 16% of exports (see Figure 1). Indirect sales account for 70% of the total wine sales, with a predominant reliance on food retail. Less than one fourth is supplied to discount retailers. Direct-to-consumer sales and distribution via gastronomy together represent over 15% of producers’ reported sales volumes.

Figure 1.

Distribution of German wine (survey results for 2023).

The data underline regional differences in German wine distribution for “mass market” (less than EUR 5 per liter) versus “value market” segments (on average, EUR 5 or more) (see Table 3). Direct-to-consumer sales are significantly higher in the regions of Rheinhessen, Mosel, and Franken, while Baden, Saale-Unstrut, and Württemberg exhibit a skew towards indirect sales. For the latter, cooperatives have a higher production share. Indeed, the members of one cooperative in the wine region of Saale-Unstrut (Winzervereinigung Freyburg-Unstrut) own almost half of the total regional vineyard area. The Palatinate wine producers profit significantly from on-premises sales (e.g., (wine) tourism), with an above-average distribution supplying gastronomy. Three regions were found to be more export-oriented (i.e., Mosel, Rheingau, Rheinhessen). Pearson correlations show statistically significant associations between wine-growing regions and distribution channels. A small negative correlation exists between the region and sales via gastronomy (r = −0.077, p = 0.050) and via discount retail (r = −0.154, p < 0.001). No significant correlations were found between the region and the direct-to-consumer (r = 0.072, p = 0.067), specialist retail (r = 0.021, p = 0.591), indirect e-business (r = −0.003, p = 0.931), food retail (r = −0.054, p = 0.168), or export (r = −0.013, p = 0.745) channels.

Table 3.

Wine distribution by wine region: split of value versus mass channel distribution *.

3.3. Strategically Determined Channel Approaches

The survey revealed distinct distribution patterns for wine producers of different sizes (see Table 4). Large-scale producers (≥1 million bottles), on average, primarily distribute indirectly through retailers (38%) and discount chains (26%) and have strong export engagement (16%). Direct-to-consumer sales account for only 5% of their distribution, and specialist trade, gastronomy, and indirect e-business are of even lower relevance. In contrast, small-scale producers (<250,000 bottles) show a preference for DTC sales, which account for 64% of their market supply. Specialist retail (13%) and gastronomy (12%) also constitute relevant channels, whereas food retail and indirect e-business channels are found to play a minor role (4% and 2%, respectively). Notably, none of the surveyed small-scale producers reported relevant sales via discount partners. For the distribution of medium-sized producers (250,000–1,000,000 bottles), on average, 47% was reported to occur through direct-to-consumer sales, followed by 21% through specialist retail and 13% through gastronomy. For medium-sized wine producers, food retail chains constitute about one tenth of their distribution. They are also engaged in export and indirect e-business sales, whereas discount chains are not supplied by these producers. The analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Scheffé post hoc analysis, statistically validated the significant differences in distribution channel usage by business size. DTC sales were found to be significantly more prevalent among small-sized producers compared to both medium-sized (mean difference = +23.5%, p < 0.001) and large-scale (+52.3%, p < 0.001) producers. This corroborates the descriptive data. In contrast, large wineries make significantly greater use of food retail channels (+34.1% vs. small-sized wineries, p < 0.001) and discount channels (+9.9% vs. small-sized wineries, +10.0% vs. medium-sized wineries, p < 0.001). The specialist retail channel is significantly more important for medium-sized and large-scale wineries compared to small-sized wineries (−10.0% and −9.3%, respectively; both p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were observed for gastronomy or indirect e-business channels, suggesting relatively uniform engagement across business sizes. Engagement with export exhibited a small but significant difference between medium-sized and small-sized wineries (+4.7%, p = 0.021).

Table 4.

Channel mix by producer size—survey results.

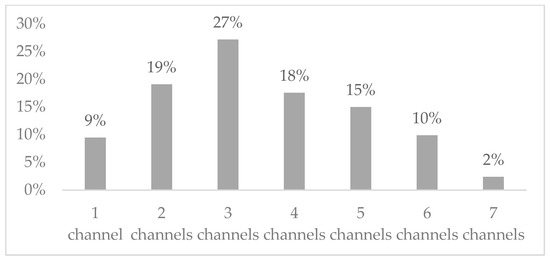

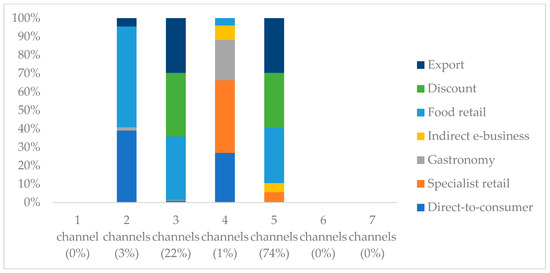

Distribution strategies further differ according to the number of channels used. Most wine producers operate with two to four channels (Figure 2). The most common configuration consists of three channels (27%), followed by two (19%) and four (18%). Only 9% of wine estates concentrate on a single channel, while only 2% distribute through seven channels. In addition to the number of channels served, the ranking of preferred distribution formats offers further insight into producers’ strategic priorities: DTC sales (28%), gastronomy (24%), and specialist retail (18%) are the most frequently cited among the top three channels.

Figure 2.

Multichannel distribution strategies: number of channels served (survey results).

The results of the statistical analyses provide support for the dependence of channel diversity on the producer size and business model. Small-sized producers primarily use up to three channels (>60%, see Table 5). Medium-sized producers operate with between two and six channels. Large-scale producers predominantly manage five or more channels (88%). Phi (φ = 0.661, p < 0.001) and Cramér’s V (V = 0.468, p < 0.001) indicate a clear, moderate-to-strong association between channel choice and company size. The negative Pearson (r = −0.166, p < 0.001) and Spearman (ρ = −0.132, p < 0.001) correlation coefficients reveal a weak but statistically significant negative linear relationship, suggesting that larger companies tend to utilize higher numbers of channels.

Table 5.

Multichannel mix by size—survey results.

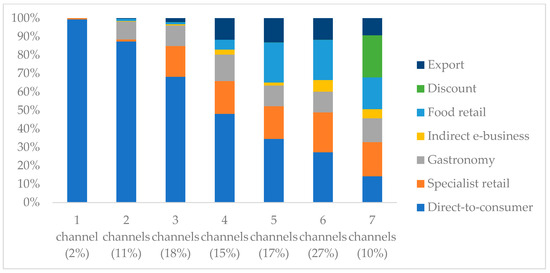

Figure 3 illustrates a changing pattern of sales channel usage among wine estates as they adopt more sales channels, highlighting that channel diversification is realized via both indirect e-business and retail partners. Estates concentrating on a maximum of two channels distribute directly and predominantly combine direct-to-consumer sales with supplying gastronomy. Less than 15% of the wine estates’ overall production is distributed via one or two channels only. As the number of channels increases, the share of direct-to-consumer sales declines, reaching just one fourth when six channels are served and only 14% in the case of distribution via seven channels, while other channels, especially specialist retail, food retail, and export, gain in relevance. Export and discount channels appear primarily in highly diversified portfolios.

Figure 3.

Channel-specific share of bottle sales per number of channels used (wine estates).

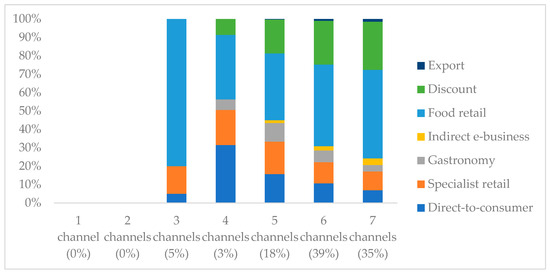

In contrast, cooperatives reported using a minimum of three channels, and the majority of the volume is generated by cooperatives utilizing six or seven channels, demonstrating a strong reliance on multichannel combinations (Figure 4). Indirect sales represent the core in cooperatives’ distribution. Cooperative sales with three to five channels cumulatively account for one quarter of cooperative production. They are key partners for the German food retail sector. With increasing channel numbers, the distribution becomes more balanced, but food retail sales play a dominant role for producers. Export activities are found to be very limited, even in the case of omnichannel strategies.

Figure 4.

Channel-specific share of bottle sales per number of channels used (cooperatives).

Cellars exhibit a distribution profile (see Figure 5) where the majority operate with five channels (74%). This dominant group is complemented by a smaller subgroup (22%) operating with three channels. In both cases, sales are concentrated in food retail, discount, and export, with each accounting for 30% of the reported sales—the basis of the predominantly mass-producing cellars. No cellars reported using either one or more than five channels.

Figure 5.

Channel-specific share of bottle sales per number of channels used (cellars).

The statistical analyses confirmed that cooperatives operate, on average, across 5.7 channels (SD = 1.05), which is a higher number than that observed for both wine estates and cellars. Wineries and cellars each use an average of 3.3 channels (SD = 1.44 and SD = 1.18, respectively). These differences are also reflected in the 95% confidence intervals: 5.4–6.0 for cooperatives, 3.2–3.5 for wineries, and 2.7–4.0 for bottling companies.

3.4. Typologies and Profiles

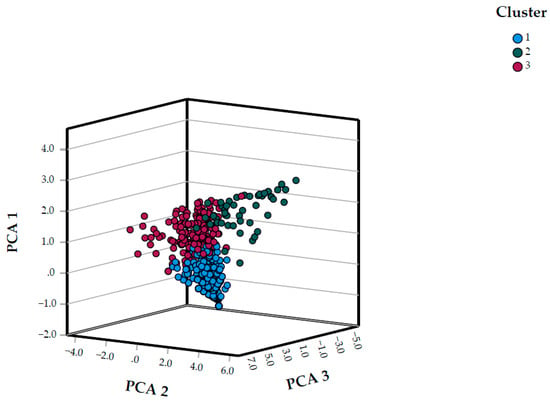

To investigate latent structures in wine producers’ distribution strategies and reduce the dimensional complexity, a PCA was conducted. Three components with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, collectively explaining 57% of the total variance. Varimax rotation was applied to enhance the interpretability, and standardized factor scores were calculated using the regression method. The first component captured a contrast between DTC distribution and retail-based multichannel models. It loaded positively on food retail and discount sales but negatively on DTC and business type. The second component reflected structural business attributes, including the business size, export activity, and specialist retail. The third component was associated with regional and traditional distribution patterns, contrasting gastronomy with the wine region and specialist retail. These three components served as input for the subsequent cluster analysis. A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method and the squared Euclidean distance was conducted to identify the number of clusters. The resulting dendrogram (Appendix B Figure A2) revealed a marked increase in linkage distances between the third and second cluster levels. Based on this, a three-cluster solution was selected and refined through a k-means cluster analysis, initialized using the centroids derived from the hierarchical approach. The final solution converged after nine iterations and yielded three well-separated clusters. Inter-cluster distances further confirmed the robustness of the solution, with distances of 85.5 between Clusters 1 and 2, 58.7 between Clusters 1 and 3, and 51.7 between Clusters 2 and 3. To validate the distinctiveness of the clusters, an ANOVA was conducted across the variables. Significant differences were observed for nearly all variables (p < 0.001), with particularly high F-values for DTC (F = 1313.72), food retail (F = 885.85), and specialist retail (F = 233.05). Only the variable “wine region” approached significance, although it did not ultimately reach significance (F = 2.99, p = 0.051). These results indicate substantial variance between clusters in terms of both structural characteristics and distribution behavior. However, it is important to note that the F-values serve descriptive purposes only, since cluster membership was determined precisely to maximize between-group differences, and the p-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The resulting cluster solution reveals three distinct producer profiles (Figure 6). Cluster 1 (63% of population) consists of small-sized wine estates that rely heavily on direct-to-consumer sales. These producers operate with an average of three distribution channels, with DTC accounting for 84% of sales. In this cluster, gastronomy and specialist retail are supplied to a limited extent, while food retail, discount, and export are largely absent. Cluster 2 (8% of population) comprises large-scale producers employing a retail-focused distribution strategy. These producers operate with an average of five channels and prioritize food retail (48%), DTC (14%), specialist retail (14%), discount (11%), and export (4%). Cluster 3 (29% of the population) represents hybrid-oriented strategies with an average of four channels and a more balanced distribution mix: DTC remains relevant (33%), but significant shares are also generated through specialist retail (28%), gastronomy (16%), and export (13%).

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional scatterplot of cluster assignment based on factor scores from PCA (each point represents a wine producer; colors indicate cluster membership (k-means)).

3.5. Transformation Perspective

The stated export share of 16% of the German wine production in the survey supports the officially stated export volume of 1.2 million hectoliters of German wine [38]. In 1990, German wine exports amounted to 2.6 hectoliters, and, in 2000, they totaled two million hectoliters [62,63], accounting for 20% of the year’s production. Clearly, German wine was not able to profit from increasing global wine trade, but it did rebound from the negative export trend, which caused a low in 2017 of less than one million hectoliters, representing just 10% of the German wine production [64].

Our efforts to conduct an analysis of evolutionary trends in the on-premises consumption of German wine suffered from a lack of reliable historic data in the literature for comparison. In addition, the closure of restaurants and on-premises wine consumption events during the pandemic certainly disrupted trends. Our empirically derived data stating that about 5% of production was distributed via on-premises partners emphasize the relevance of on-premises sales for German wine producers and fill a gap in quantification.

For home consumption, we compared the survey results with published market reports built upon scanned retail sales data and selective household inquiries, which were required to adjust the survey data by extracting export and on-premises distribution information, as well as weighting to account for the total German wine supply population and structure (see Appendix C Table A1). Since 2008, indirect retail channels (including food retail, discount, and wine shops) have gained in their shares of German wine distribution (see Table 6). Direct-to-consumer sales, which declined from almost one third of German wine distribution in 2008 to less than one fourth in 2018, experienced a rebound in the period leading up to 2023. This development suggests the partial revitalization of direct marketing strategies among producers, potentially linked to regional identity, tourism, or renewed efforts in relationship-based marketing, especially in the aftermath of COVID-19. E-commerce (indirect e-business), for which data were not recorded in 2008, emerged as a measurable channel, reaching and maintaining a level of about 5%, reflecting digital transformation and changing consumer preferences towards convenience and online availability.

Table 6.

Distribution of German wine (home consumption).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide empirically backed transparency regarding the key distributional patterns of German wine suppliers, particularly with respect to the winery size, channel diversity, digital adoption, and market alignment. Collectively, the findings point to a fragmented and structurally constrained distribution environment. Small-sized wine estates predominantly serve direct-to-consumer channels, often exceeding 60% of their total sales volume. These patterns confirm literature-based assumptions regarding structural segmentation [44] and reflect broader industry trends in which scale enables access to infrastructure, branding, and logistics advantages [49]. Smaller producers face barriers to accessing dominant consumer channels, while larger firms benefit from economies of scale, technological infrastructure, and retail negotiation power. Indeed, they are limited in extending their reach by resource dependency. The cross-tabulation of business type and production volume reveals a strong and statistically significant association, with cooperatives and large cellars clearly dominating higher production brackets, while estates account for the majority of small-scale production. This confirms the structural polarization of the sector in terms of output volume and channel access potential. Furthermore, wine-growing regions differ significantly in their producer structures, as evidenced by the statistically significant relationship between the region and business model. Württemberg and Baden show high cooperative density, while Mosel, Pfalz, and Rheinhessen are more estate-driven.

To further explore the latent distribution logics and business model variation, the cluster analysis went beyond descriptive classification to enable a more nuanced understanding of distributional behavior by capturing multivariate patterns in strategy and structure. The resulting three-cluster solution provides an empirically grounded typology that contributes to the deeper comprehension of the German wine sector’s internal heterogeneity and supports more targeted strategic decision making and policy development. Cluster 1 represents traditional, relationship-based estates with a narrow channel focus, high reliance on DTC sales, and deep local market integration. The producers in this cluster are structurally constrained in scaling their operations and face significant barriers to entering dominant retail channels. Cluster 2, by contrast, includes industrially structured entities—primarily large-scale producers—that exhibit multichannel breadth and efficiency-driven strategies. Their distribution profiles are defined by strong integration into national food retail, discount formats, and international export, suggesting high market power and logistical capacity. Cluster 3 comprises hybrid-oriented producers pursuing a distribution strategy that maintains relevance across the DTC, specialist retail, gastronomy, and export markets. This segment combines value-driven positioning with moderate volume ambitions and may reflect an adaptive response to increasingly fragmented consumer preferences. Together, the clusters reveal not only the structural diversity of the German wine sector but also the strategic orientations that shape producers’ market behavior. By uncovering the latent logic in channel usage and aligning this with business characteristics, the cluster analysis offers a valuable lens through which to understand operational constraints, market positioning, and strategic flexibility across the industry. The clusters illustrate that business model design and distribution strategies need to fit and thereby form levers to overcome resource dependency by building a profound dynamic capability. A recent market analysis [65] outlines a framework comprising six components—comprising search engine optimization (SEO), social media engagement, pay-per-click advertising, content marketing, email automation, and data analytics—which are considered essential elements in order for breweries to effectively compete online. For the wine industry, recommendations should recognize the distribution strategies, such as those used by the wine producers in Clusters 1 and 3. The typology reported here provides a solid foundation for tailored policy support and targeted managerial action, as it recognizes that sustainable competitiveness in the wine sector depends on both structural conditions and the strategic capacity of producers to navigate an increasingly complex distribution environment.

German wine is predominantly distributed in Germany. German wine producers did not profit from the strong increase in cross-border global wine trade that exceeded 100 million hectoliters, with a value of more than EUR 38 billion, in 2022, up from less than 50 million hectoliters, worth about EUR 10 billion, in 1990 [66,67,68,69].

The buying behavior of German wine consumers has changed markedly. There is increasing polarization between buyers that are price-driven and those that seek quality and sustainability [70,71,72,73,74]. While the average price of wine in Germany remains low by international and European standards, experiential value and authenticity are appreciated [75,76]. Reduced alcohol consumption is driven by both health concerns and broader societal shifts [77,78,79,80]. Multichannel buying reflects relevant trends [81]. The high prevalence of multichannel strategies reflects an adaptive response to increasingly fragmented consumer behavior. Meanwhile, the rise of online platforms has democratized access to wine knowledge, enabling consumers to make informed choices based on peer reviews and algorithmic recommendations [44]. These dynamic changes illustrate a transformation in the global—and, certainly, the German—wine market, with implications regarding how to reach consumers [81]. Research by the German Wine Institute shows that regional preferences and consumer segmentation are becoming more influential, requiring producers to adapt their sales strategies accordingly. In addition, analyses of consumer behavior patterns in East and West Germany have revealed differing sensitivities to price, brand loyalty, and product expectations—insights that have since shaped differentiated regional marketing approaches [82]. These developments force producers to adopt individualized, value-oriented strategies while managing fragmented segments and operational complexity. This fragmentation represents both an opportunity and a challenge. Multichannel readiness, psychographic alignment, and flexibility in pricing and communication are increasingly vital. Indeed, Cluster 3 illustrates the hybrid-oriented wineries that strategically combine value-oriented DTC approaches with broader retail access, indicating that such flexibility is not just conceptually relevant but empirically observable in the German wine landscape. While price and convenience remain the most important factors driving the majority of sales, a growing share of volume and revenue is driven by consumers who are willing to pay more for wines that align with their ethical, environmental, or taste-related preferences. Strategic distribution models must therefore account for both structural diversity and evolving behavioral expectations in a rapidly transforming market landscape [37].

Contrary to literature-based assumptions, the data reaffirm the continued relevance of DTC in Germany. Direct distribution plays a significant role in the wine sector in Germany compared to other wine-producing countries, other food and beverage sectors, or consumer product sectors, where direct sales typically represent only a marginal contribution or serve the purpose of brand building in flagship stores [83,84]. For Cluster 1 populations, direct-to-consumer distribution builds the core of their business and their DNA. They need to be customer-centric and orchestrate all touchpoints of the customer journey accordingly. Direct wine sales benefit from consumers’ desire to purchase regional products in an effort to act sustainably [85,86,87,88]. Our findings highlight the structural characteristics of the German wine industry, marked by a high number of small- and medium-sized producers, strong regional identities, and long-standing customer relationships, which continue to sustain and legitimize DTC as a key pillar in wine distribution [89,90]. In light of the trends of intensifying competition and drive-out in the German wine market [91], DTC access is becoming a promising anchor, in line with predictions for the US wine industry [92]. Whereas beer, for example, predominantly relies on mass-market distribution channels and centralized marketing campaigns, with breweries typically possessing advanced technological and logistical capabilities, enabling the efficient implementation of sales and marketing strategies, advertising, and digital platforms [93], wine can profit from a personalized, consultative sales approach. Still, to ensure the sustainability of sales in the wine sector, there is a growing need to accelerate the integration of digital tools and strategies across all business models and distribution channels. This includes not only improving technological infrastructure but also rethinking how value is communicated and how consumers are engaged across digital and physical touchpoints [94]. Addressing these gaps is particularly crucial in order for smaller producers to remain competitive in a rapidly evolving market landscape.

The presented survey responses provide empirical evidence that on-premises wine consumption has recovered from the pandemic lockdowns and the subsequent loss of sales partners. The survey allowed us to determine that 40 million liters of German wine were destined to be sold on-premises, thereby underlining the relevance that restaurants and other on-premises partners have for German wine. The empirically derived data are of paramount importance, since consumers pay more for on-premises wine consumption than for home consumption. The rebound from zero sales (during the first lockdown in Germany, which started on 22 March 2020) offered the opportunity for wine producers to establish new distribution and sales relationships, but not without risks, since the hospitality industry faces difficulties in attracting and retaining staff (exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and changing work expectations), inflation, supply chain disruptions, and rising food costs [95]. Hence, distributing products via on-premises channels requires appropriate strategies and risk management, illustrated by the channel combination of Cluster 3 producers. These patterns mirror business capabilities and resource availability [96].

Wine estates need to improve their direct and digital customer engagement and reposition their offerings in a value-oriented manner [97]. Online sales, which were once a marginal phenomenon, have become a fundamental distribution pillar—not as a substitution for other channels but, rather, as a complementary building block in the design of direct-to-consumer business models [42]. This transformation has been fueled by both supply-side innovation (improved logistics, professionalized winery webshops, and curated online portfolios) and demand-side drivers (including convenience, accessibility, and the growing importance of peer recommendations and digital wine communities) [43]. The survey results provide quantifiable evidence that the shift towards indirect distribution via food retail, discount, and e-business retailers represents an evolutionary transformation rather than a caesural one, contrasting with common statements in the literature [98]. Online and hybrid formats account for a notable share of the total wine sales in Germany, highlighting the need for strengthened multichannel strategies and platform-based consumer engagement models [99]. However, in contrast to claims of substitution and dominance [100], online sales remain a complementary support in wine distribution.

The transformation of distribution channels in the German wine sector is closely linked to shifts in consumer behavior and the competitive positioning of retail formats. Traditional DTC channels extend cellar door sales to also include wine festivals, and tasting events play a vital role in the business models of many wine estates [101]. Still, it is unclear and remains to be explored whether younger consumers, who increasingly value convenience and digital access, will be attracted by on-site experiences [102,103]. In response, many wine estates have reoriented their strategies, selling online or serving e-commerce platforms and investing in wine tourism to maintain a level of experiential value. Such business model extension can be costly and time-consuming, placing strain on small producers [104]. The notion of the “cellar door” has evolved into a digital interface, often complemented by storytelling, virtual tastings, and social media engagement [105,106,107,108]. Winery webshops allow the producer to keep the customer within their realm, but wine-specific e-retailers (e.g., wirwinzer.de, geileweine.de) and large platforms (e.g., www.amazon.de/wein-angebote/s?k=wein+angebote (accessed on 28 August 2025)) are highly professional in their customer care and logistics. The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst, accelerating digital adoption across all consumer groups and pushing even conservative producers towards online solutions. Recent studies have highlighted the role of digital engagement and consumer knowledge in shaping online wine purchasing behavior [109], supporting our observations for indirect e-business. These dynamics illustrate the complex reconfiguration of distribution structures in response to both consumer-driven and systemic changes in the market. Multichannel strategies combining physical and digital access points are increasingly seen as a prerequisite for market success [110]. Larger wine estates display particularly strong reliance on sales via third-party e-business platforms [43]. This pattern supports claims in the literature that digital maturity in the wine sector is strongly associated with scale and institutional capacity [42].

Our results provide less support for suggestions in the literature that production and marketing should be divided [111]. Indeed, an increase in dependency on indirect sales via retail and discount chains bears substantial risks. The market power of these channels is high and continues to increase [51]. Retail distribution has experienced consolidation, with discounters such as Aldi and Lidl dominating the mass market. Their market power prevents producers from achieving high margins, eventually not even covering the full costs of suppliers [112,113]. In an aim to keep and win customers, retailers and supermarkets have upgraded their wine assortments, store presentation, and advisory services, narrowing the distinction between general food retail and traditional wine specialists [114]. While the food retail sector offers unparalleled reach to German consumers, its increasing consolidation presents challenges for small- and medium-sized wine producers. Although listing products in food retail channels allows wine producers to sell high quantities with few activities and to access distant customers, producers face substantial difficulties in negotiating favorable prices and conditions. Price pressure, rigid contract terms, and the risk of being replaced by private labels or promotional items undermine the long-term stability of these business relationships. Indeed, our data point to eventual bandwaggoning effects [115,116] as there are smaller producers that show a rich omnichannel distribution: in light of limited resources, producers need to reflect on the costs of serving multiple channels and eventual limitations in degrees of freedom that bind them to serving larger customers with often lower price levels or margins in years of smaller yields. Consequently, producers profit from direct-to-consumer sales and niche distribution, where greater autonomy over pricing and brand positioning can be maintained [117,118]. Our typology can provide orientation for business model fitting to distribution strategies.

To address the identified structural disparities, sectoral strategies and policy instruments could support collaborative logistics, shared digital infrastructure, and cooperative marketing frameworks [110]. Policymakers should prioritize support for the digital transformation of small- and medium-sized wineries by establishing dedicated funding instruments and advisory programs. Such initiatives allow producers to implement DTC e-commerce models, professionalize their web presence, and utilize customer relationship management systems, thus enhancing their digital visibility and market access. In parallel, collaborative logistics and shared infrastructure platforms should be promoted to enable smaller producers to pool resources for warehousing, packaging, and last-mile delivery. In support of experiential formats, which continue to play a central role in value market segments such as DTC business models, wine tourism infrastructure and cross-sector partnerships should be reinforced [119,120]. Regional governments can contribute by investing in visitor experiences and digital platforms for wine tourism and by fostering collaboration between wineries, gastronomy, and cultural actors to enhance consumer engagement and regional value creation. Furthermore, regulatory bodies should closely monitor consolidation trends and power asymmetries in the retail sector. Guidelines on fair trading are essential to protect wine producers from exploitative listing practices, rigid contract conditions, and pricing strategies that will erode their margins and long-term viability. To foster export sales, targeted export promotion is also recommended [121,122]. Trade missions, joint international marketing campaigns, and the provision of strategic market intelligence could help producers, particularly those in the premium and sustainability segments, to gain access to new and emerging markets. These measures would also support the restoration of Germany’s international wine reputation and unlock its underutilized export potential.

5. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study include its one-industry and one-country survey and its focus on supply-side data, which were only partially triangulated with consumer research. Future studies should deepen consumer insights, explore longitudinal trends in greater statistical depth, and examine international comparability. The data collection process reflects the state of the market in 2023, and, despite a high response rate and market coverage, the fragmentation of the industry must be taken into account when interpreting the data. Similarly, some German wine regions with low participation may need further assessment. Finally, all of the findings rely on standardized self-reporting by producers; the possibility of response bias, including socially desirable answers or strategic reporting, cannot be ruled out.

This study fills a gap in data in this area and explores strategic configurations; therefore, it can serve as a basis for conducting further research to foster market transparency and strategic implications. Future researchers are invited to examine how wine estates of different sizes adapt their distribution strategies over time, especially in response to external shocks such as COVID-19. Economic performance analyses of distribution strategies and cluster belonging would also be valuable. Additionally, longitudinal studies could be carried out to assess the durability and success of international digital transitions in the sector. More detailed consumer-side data, especially concerning psychographic profiles, digital engagement, and value orientation, would also allow for improved producer–consumer alignment. An assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of different channels, along with international comparisons, would allow practitioners to configure their strategies to increase value creation. Finally, business model innovations such as wine platforms and e-marketplaces deserve closer examination as potential enablers of equitable access and resilience in a structurally diverse production landscape.

6. Conclusions

Distribution determines how products move from producers to consumers. It affects product availability, customer satisfaction, producers’ and partners’ incomes, and overall market penetration. Choosing the right distribution channels—whether direct, through commercial partners, or online—can significantly impact sales performance and brand perception. Distribution plays a central role in the wine sector, where product accessibility, regional identity, and consumer experience are closely intertwined. The findings confirm the continued dominance of indirect retail, particularly food retail, while also highlighting a rebound in direct-to-consumer sales, value market approaches, and on-premises distribution. The results of this study contribute to closing data gaps by underlining that gastronomy has been re-established as a relevant distribution channel and that German wine has not profited from global growth in wine trading. Multichannel distribution is becoming increasingly relevant as wineries seek to diversify their sales outlets and reduce the dependency on traditional intermediaries. This includes DTC sales through winery tasting rooms and online platforms, partnerships with on-trade (e.g., restaurants and wine bars) and off-trade (e.g., retail and supermarkets) channels, and exports through specialized distributors. Multichannel strategies vary significantly in their depth and reach depending on different business models.

A sales strategy can provide a framework indicating how wineries should position their offerings, differentiate themselves in a highly fragmented market, and engage both trade partners and end consumers. Particularly for small and medium-sized producers, strategic sales planning is critical in building a brand identity and accessing profitable market segments. The findings of this study reveal that channel selection strongly depends on the size and the business model employed. Multichannel strategies are increasingly adopted across the sector, yet their implementation varies significantly. By documenting the distributional realities of a structurally fragmented market, this study contributes to closing a critical data gap from the producer side and offers a robust empirical foundation for strategic, sector-wide development. It lays the groundwork for future longitudinal, international, and comparative research on digital transformation and market alignment in the wine industry. As the market continues to evolve, ongoing data collection will be essential to maintain transparency and inform both policy and strategy.

Author Contributions

M.D. and K.K. conceived and designed the study and market research; M.D. and K.K. performed the market research; M.D. and K.K. analyzed the data; M.D. and K.K. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EIP-AGRI “Wein-Mehrweg”, grant number [2014DE06RDRP003].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The thirteen German wine regions [123], Reproduced with permission from Deutsches Weininstitut (DWI). Werbemittelkatalog 2025, published by DWI, 2025.

Appendix B

Figure A2.

Dendrogram of the hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method and the squared Euclidean distance.

Appendix C

Weights were calculated using the following scheme.

Table A1.

Weighting scheme of sample versus overall population.

Table A1.

Weighting scheme of sample versus overall population.

| Business Type | Sample (N) | Population (N) | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winery | 591 | 7200 | 4.36 |

| Cooperative | 49 | 140 | 1.02 |

| Cellar | 15 | 50 | 1.19 |

| Total | 655 | 7390 | – |

References

- Piercy, N.F. The strategic sales organization. Mark. Rev. 2006, 6, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.; Beeler, L. The state of selling & sales management research: A review and future research agenda. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Day, G.S.; Rangan, V.K. Strategic channel design. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1997, 38, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf, A.; Cravens, D.W.; Piercy, N.F. Examining business strategy, sales management, and salesperson antecedents of sales organization effectiveness. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2001, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, M.; Kunisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Collis, D.J.; Foss, N.J.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Prescott, J.E. Corporate strategy and the theory of the firm in the digital age. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1695–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.W.; Ahmed, W. Understanding dynamic distribution capabilities to enhance supply chain performance: A dynamic capability view. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 2822–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmare, A.; Zewdie, S. Omnichannel retailing strategy: A systematic review. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2022, 32, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikbal, M.; Saragi, S.; Sitanggang, M.L. The effect of sales distribution channels and promotion policies on consumer buying behavior and its impact on sales volume. Int. J. Bus. Rev. (Jobs Rev.) 2021, 4, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Acquila-Natale, E. The future of e-commerce: Overview and prospects of multichannel and omnichannel retail. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicea, C.; Marinescu, C.; Banacu, C.S. Multi-channel and omni-channel retailing in the scientific literature: A text mining approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 18, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalamäki, M.J.; Joensuu-Salo, S. Digitalization and strategic flexibility–a recipe for business growth. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2022, 29, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahirov, N.; Glock, C.H. Manufacturer encroachment and channel conflicts: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 302, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Competitors or frenemies? Strategic investment between competing channels. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantù, C.; Martinelli, E.M.; Tunisini, A. Marketing channel transformation in Italian SMEs. Int. J. Glob. Small Bus. 2022, 13, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W. Design of the Multichannel System. In Multichannel Marketing: Strategy–Design–Digital Technology; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024; pp. 433–468. [Google Scholar]

- Kabadayi, S. Adding direct or independent channels to multiple channel mix. Direct Mark. Int. J. 2008, 2, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Consumers’ preferences for wine attributes: A best-worst scaling analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Netzer, Y. Long-term trends of global wine market. Agriculture 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhut Kompaniets, O. Sustainable competitive advantages for a nascent wine country: An example from southern Sweden. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2022, 32, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Garcia, E.; Martinez-Falco, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Georgantzis, N. Value creation in the wine industry—A bibliometric analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R.; Loose, S. State of the International Wine Market in 2022: New market trends for wines require new strategies. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2024; OIV: Dijon, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, B.; Cardebat, J.M.; Back, R.M.; Gaeta, D.; Pinilla, V.; Rebelo, J.; Jara-Rojas, R.; Schamel, G. Wine industry perceptions and reactions to the COVID-19 crisis in the Old and New Worlds: Do business models make a difference? Agribusiness 2022, 38, 810–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; Canales, E.; Low, S.A.; Boys, K. Local food supply chain dynamics and resilience during COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. A comparison of the importance of wine supplier quality attributes for on-premise and off-premise wine retail establishments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 2795–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, S.; Wilkinson, C.; Thornton, L.; Feng, X.; Richmond, R. Online alcohol sales and home delivery: An international policy review and systematic literature review. Health Policy 2021, 125, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.J. A model for wine list and wine inventory yield management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livat, F.; Remaud, H.; McHale, A. The puzzle of wine price in restaurants. Wine Bus. J. 2023. Available online: https://wbj.scholasticahq.com/article/74106 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Gil, I.; Berenguer, G.; Ruiz, M.E. Wine list engineering: Categorization of food and beverage outlets. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Luongo, S.; Reinhard, K. Marketing metrics in the wine retailing industry. Symphonya. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2023, 2, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Zhang, W. Wine distribution channel systems in mature and newly growing markets: Germany versus China. In Proceedings of the Academy of Wine Business Research Conference, St. Catharines, ON, Canada, 12–15 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, R. From sales force automation to digital transformation: How social media, social CRM, and artificial intelligence technologies are influencing the sales process. In A Research Agenda for Sales; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- van Burg, E.; Podoynitsyna, K.; Beck, L.; Lommelen, T. Directive Deficiencies: How Resource Constraints Direct Opportunity Identification in SMEs. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kump, B.; Schweiger, C. Mere adaptability or dynamic capabilities? A qualitative multi-case study on how SMEs renew their resource bases. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2022, 14, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; Kellermanns, F.W.; López-Fernández, M.C. Dynamic capabilities and SME performance: The moderating effect of market orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 162–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Londoño, G.; Ruiz-Moreno, F.; Sellers-Rubio, R. Modelling the group dynamics in the wine industry. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2023, 35, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2024/2025; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Habann, F.; Zerres, C.; Zaworski, L. Investigating the segment specific preferences for hedonic and utilitarian online-shop characteristics: The case of German online wine shops. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2018, 12, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Selvaggi, R.; Pecorino, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Nayga, R.M. Assessing experiential augmentation of the environment in the valuation of wine: Evidence from an economic experiment in Mt. Etna, Italy. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Thach, L. Wine tourists’ use of sources of information when visiting a USA wine region. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Seegebarth, B.; Kissling, M.; Sippel, T. Social cues and the online purchase intentions of organic wine. Foods 2020, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, M.; Sparacino, A.; Merlino, V.M.; Brun, F.; Massaglia, S.; Blanc, S. Exploring consumer sentiments and opinions in wine E-commerce: A cross-country comparative study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Hoffmann, D. Online wine purchasing: Influencing factors and consumer segments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Amadieu, P.; Maurel, C.; Viviani, J.-L. Intangible expenses, export intensity and company performance in the French wine industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, Bordeaux, France, 9–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R.; Zemsky, P. A demand-based perspective on sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G. Geisenheimer Weinkundenanalyse—Repräsentativbefragung zu Kauf-und Konsumverhalten bei Wein; Hochschule Geisenheim University: Geisenheim, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.; Thach, E. Analyzing German winery adoption of Web 2.0 and social media. J. Wine Res. 2016, 27, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.; Lee, D.-J.; Han, K.; Hwang, M.; Ahn, J.-H. Channel capabilities, product characteristics, and the impacts of mobile channel introduction. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 30, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilia, R.D. History of Channels of Distribution and Their Evolution in Marketing Thought. In Proceedings of the Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 16–19 May 2019; pp. 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Weinbauverband, D. Trinkweinbilanz 22/23; DWV: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BMEL. Agrarpolitischer Bericht der Bundesregierung; Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (BMEL), Referat 721: Berlin, Germany, 2023.

- Coelho, F.; Easingwood, C.; Coelho, A. Exploratory evidence of channel performance in single vs multiple channel strategies. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E.; Cohen, A.H.; Christ, P.F.; Mehta, R.; Dubinsky, A.J. Provenance, evolution, and transition of personal selling and sales management to strategic marketing channel management. J. Mark. Channels 2020, 26, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dominguez, L.V. Channel evolution: A framework for analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loose, S.; Pabst, E. Current State of the German and International Wine Markets. Oceania 2018, 67, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Guide to Strategic Business Management for for Small Entrepreneurs in the Wine Industry and Beyond; UVK Verlag: München, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Gensler, S.; Weiber, R.; Weiber, T. Multivariate analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 10, pp. 973–978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Sabol, M.A. Overview of Multivariate Data Analysis, An. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1853–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Crum, M.; Nelson, T.; de Borst, J.; Byrnes, P. The use of cluster analysis in entrepreneurship research: Review of past research and future directions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 60, 961–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2004/2005; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2007/2008; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2018/2019; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, B. Digital Marketing Strategy for Breweries: A Customer Growth Playbook. Emulent Insights. 2025. Available online: https://emulent.com/blog/digital-marketing-strategy-for-breweries/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Roca, P. State of the vitivinicultural world in 2022. In OIV Press Conference; International Organisation of Vine and Wine: Dijon, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Vitiviniculture Situation 2016; OIV: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Vitiviniculture Situation 2013; OIV: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. World Statistics 2010; OIV: Porto, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, M.; Spry, A. Gen Z supports sustainability—And fuels ultra-fast fashion. How does that work? J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2024, 28, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kasem, M.S.; Hamada, M.; Taj-Eddin, I. Customer profiling, segmentation, and sales prediction using AI in direct marketing. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 4995–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Feinberg, R.A. The LOHAS (lifestyle of health and sustainability) scale development and validation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesano, G.; Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Gioacchino, P.; D’Amico, M. What’s in organic wine consumer mind? A review on purchasing drivers of organic wines. Wine Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Thrassou, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Schifani, G.; Galati, A. Factors affecting consumer preferences for “natural wine” An exploratory study in the Italian market. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2463–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Donate, M.C.; Romero-Rodríguez, M.E.; Cano-Fernández, V.J. Wine consumption preferences among generations X and Y: An analysis of variability. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3557–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions, preferences and willingness-to-pay for wine with sustainability characteristics: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, H.; Rossow, I.; Brunborg, G.S. Adolescents drink less: How, who and why? A review of the recent research literature. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018, 37, S98–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, S.; Gajos, G. Alcohol, health loss, and mortality: Can wine really save the good name of moderate alcohol consumption? Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghvanidze, S.; Franco Lucas, B.; Brunner, T.A.; Hanf, J.H. Unveiling wine and cannabis consumption motivations: A segmentation study of wine consumers in Germany. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2025, 37, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, E.; Agnoli, L.; Charters, S.; Georgantzis, N. Feelings and alcohol consumption. J. Econ. Psychol. 2024, 104, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Hoffmann, D. Neue Weinkunden-Segmentierung in Deutschland. In Proceedings of the 37th World Congress of Vine and Wine and 12th General Assembly of the OIV, Mendoza, Argentina, 9–14 November 2014; p. 07002. [Google Scholar]

- DWI. Deutscher Wein Statistik 2022/2023; DWI: Mainz, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Ko, E.; Kim, E.Y.; Mattila, P. The Role of Fashion Brand Authenticity in Product Management: A Holistic Marketing Approach. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J. Wine Industry Report Offers Insight Into DTC Sales In 2023. Forbes. 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jillbarth/2023/01/25/wine-industry-report-offers-insight-into-dtc-sales-in-2023/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Schenk, T.A. Windeln und Badreiniger vom Biobauern? Neue Strategien der Direktvermarktung. Aktuelle Trends 2010, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Climate Sentiment—Klimasorgen Beeinflussen das Verbraucherverhalten in Deutschland; Deloitte: Tirana, Albania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DPA. Lebensmittelherkunft Ist Für Deutsche Wichtiger Als Preis; Yumda Food & Drinks Business: Nürnberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nestlé. So is(s)t Deutschland—Ein Spiegel der Gesellschaft; Nestlé: Frankfurt Main, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M. The German Wine Market: A Comprehensive Strategic and Economic Analysis. Beverages 2018, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, G.L.; Perano, M.; Presenza, A.; Abbate, T. Does innovation propensity influence wineries’ distribution channel decisions? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, B. Deutscher Weinbau vor dem Aus? Getränke News. 2025. Available online: https://getraenke-news.de/deutscher-weinbau-vor-dem-aus/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Morris, R. Smaller Wineries Lead Economic Turnaround in the US. 2025. Available online: https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2025/06/smaller-wineries-lead-economic-turnaround-in-the-us/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Dunne, A.; Malec, P.; Shank, A.; Foral, E.; Rethmeier, H. A Strategic Audit of a Company in the Alcoholic Beverages Industry: Anheuser-Busch InBev. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Holl, A.; Rama, R.; Hammond, H. COVID-19 and Business Digitalization: Unveiling the Effects of Concurrent Strategies. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpitz, K. Gastrosterben—Fast jeder vierte Gastronom überlegt aufzugeben. HB Online. 2024. Available online: https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/handel-konsumgueter/insolvenzen-fast-jeder-vierte-gastronom-ueberlegt-aufzugeben/100053205.html (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter. Bericht zur Lage der VDP.Prädikatsweingüter 2024; VDP: Mainz, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- VDP. Bericht zur Lage der VDP Prädikatsweingüter 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.vdp.de/de/bericht-zur-lage-der-vdppraedikatsweingueter-2024-1 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Hirche, M.; Loose, S.; Lockshin, L.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. Distribution velocity in wine retailing. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Hajizada, S.; Kovalyova, I.; Sakhbieva, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanska, I.; Hrytsyna, L.; Kharun, O.; Matviiets, O. E-commerce and M-commerce as Global Trends of International Trade Caused by the Covid-19 Pandemic. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafel, M.C. Investigating the Characteristics and the Economic Impact of Tourism in German Wine Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, Hochschule Geisenheim, Geisenheim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Janšto, E.; Chebeň, J.; Šedík, P.; Savov, R. Influence of labelling features on purchase decisions: Exploratory study into the Generation Z beverage consumption patterns. Amfiteatru Econ. 2024, 26, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]