Impact of Foliar Application of Winemaking By-Product Extracts in Tempranillo Grapes Grown Under Warm Climate: First Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

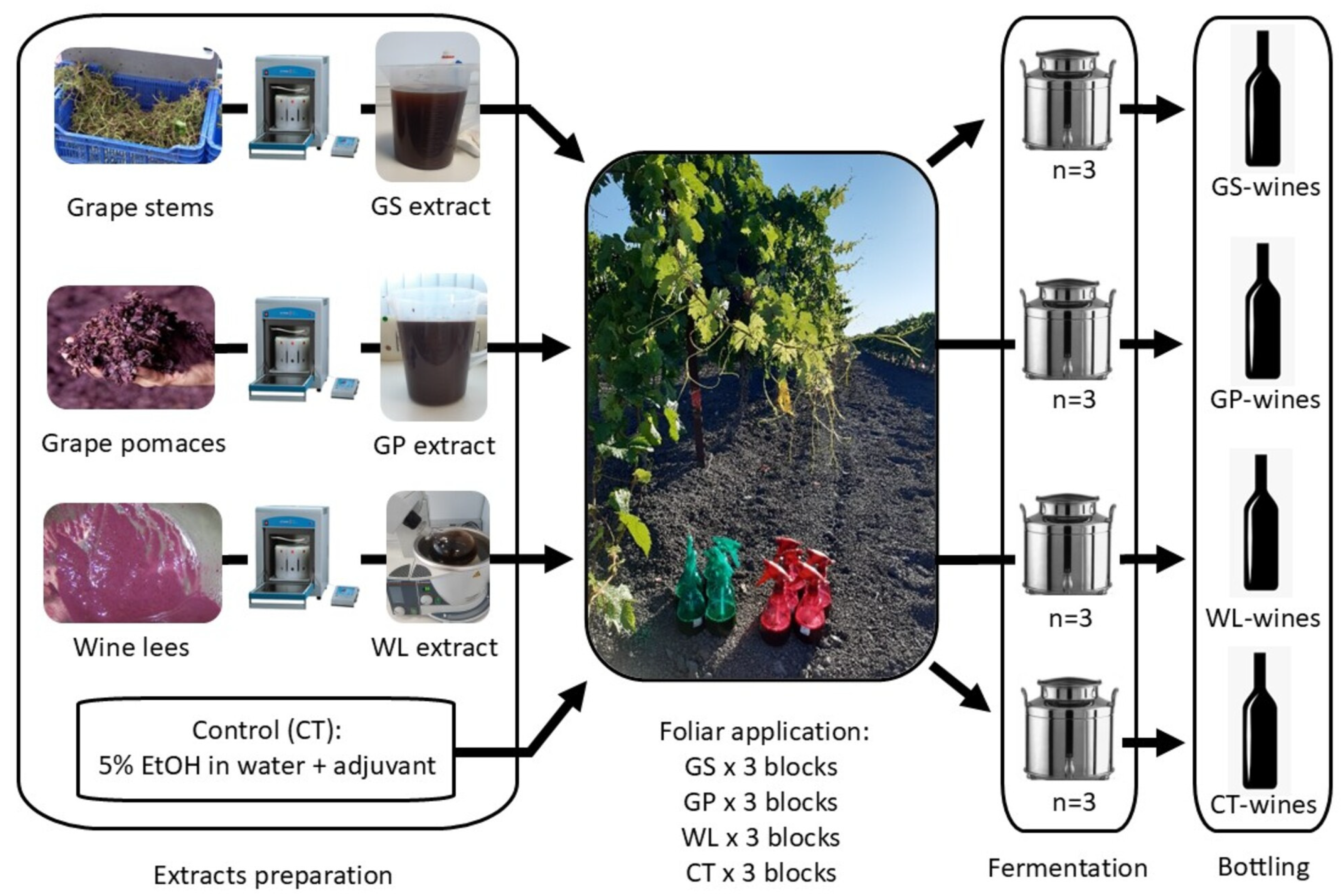

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Winemaking By-Product Samples

2.2. Grapevines

2.3. Extract Preparation

- For the extraction of grape stems, 10 g of ground sample, 80% ethanol in water as the extraction solvent, an extraction temperature of 25 °C, a system power of 750 W, and an extraction volume of 50 mL were selected. The extraction time was set to 15 min.

- For grape pomaces, 10 g of ground sample was selected, 50% ethanol in water was utilised as the extraction solvent, an extraction temperature of 100 °C, system power of 750 W, and an extraction volume of 50 mL were used. The extraction time was 30 min, with a preheating time of 5 min.

- For the extraction of wine lees, the procedure was repeated using 10 g of ground sample, 50% ethanol in water as the extraction solvent, an extraction temperature of 100 °C, system power of 750 W, and an extraction volume of 50 mL. The extraction time was reduced to 15 min, with a preheating time of 5 min.

2.4. Grapevine Treatments

2.5. Winemaking Procedure

2.6. Oenological Parameters

2.7. Colour and Colorimetric Measurements

2.8. Sensory Analysis

2.9. Statistical Software

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. By-Product Extraction

3.2. Oenological Parameters of Grapes at Harvest

3.3. Wine Composition During Winemaking and Ageing Stages

3.3.1. Oenological Parameters

3.3.2. Phenolic Content Evolution

3.3.3. Colour and CIELab Evolution

3.4. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soto-Vázquez, E.; Río-Segade, S.; Orriols-Fernández, I. Effect of the winemaking technique on phenolic composition and chromatic characteristics in young red wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, S.E.; Tarara, J.M.; Mee, D.L.; Ferguson, J.C. Separation of sunlight and temperature effects on the composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot berries. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 2002, 53, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitayama, M.; Hashizume, K. Loss of anthocyanins in red-wine grape under high temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Sugaya, S.; Gemma, H. Decreased anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berries grown under elevated night temperature condition. Sci. Hort. 2005, 105, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo Bastante, M.J.; Gordillo Arrobas, B.; Hernanz Vila, M.D.; Escudero Gilete, M.L.; González-Miret Martín, M.L.; Heredia, F.J. Effect of the time of cold maceration on the evolution of phenolic compounds and colour of Syrah wines elaborated in warm climate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse-Valverde, N.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; López-Roca, J.M.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; Bautista-Ortín, A.B. The extraction of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins from grapes to wine during fermentative maceration is affected by the enological technique. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5450–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Allamy, L.; Schüttler, A.; Rauhut, D.; Thibon, C.; Darriet, P. What is the expected impact of climate change on wine aroma compounds and their precursors in grape? OENO One 2017, 51, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hort. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Cocetta, G.; Trivellini, A.; Vernieri, P.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants and crop responses: A review. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2015, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Gonçalves, B.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I. The role of biostimulants as alleviators of biotic and abiotic stresses grapevine: A review. Plants 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portu, J.; López-Alfaro, I.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; López, R.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Changes on grape phenolic composition induced by grapevine foliar applications of phenylalanine and urea. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Sabbatini, P.; Tombesi, S.; Norrie, J.; Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Palliotti, A. Effects of a biostimulant derived from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum on ripening dynamics and fruit quality of grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 232, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.C.; Popescu, M. Yield, berry quality and physiological response of grapevine to foliar humic acid application. Bragantia 2018, 77, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portu, J.; López, R.; Baroja, E.; Santamaría, P.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Improvement of grape and wine phenolic content by foliar application to grapevine of three different elicitors: Methyl jasmonate, chitosan, and yeast extract. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladines-Quezada, D.; Fernández-Fernández, J.; Moreno-Olivares, J.; Bleda-Sánchez, J.; Gómez-Martínez, J.; Martínez-Jiménez, J.; Gil-Muñoz, R. Application of elicitors in two ripening periods of Vitis vinifera L. cv Monastrell: Influence on anthocyanin concentration of grapes and wines. Molecules 2021, 26, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Romanazzi, G.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P. A review of the use of biostimulants in the vineyard for improved grape and wine quality: Effects on prevention of grapevine diseases. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Gamboa, G.; Moreno-Simunovic, Y. Seaweeds in viticulture: A review focused on grape quality. Cienc. Tec. Vitivinic. 2021, 36, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Fucile, M.; Mattii, G.B. Biostimulants in viticulture: A sustainable approach against biotic and abiotic stresses. Plants 2022, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Geelen, D. Developing biostimulants from agro-food and industrial by-products. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-García, A.I.; Wilkinson, K.L.; Culbert, J.A.; Lloyd, N.D.R.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Accumulation of guaiacol glycoconjugates in fruit, leaves and shoots of Vitis vinifera cv. Monastrell following foliar applications of guaiacol or oak extract to grapevines. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, J.A.; Lizama, V.; Alvarez, I.; García, M.J. Impact of rutin and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) extract applications on the volatile and phenolic composition of wine. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gómez, R.; Zalacaín, A.; Pardo, F.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Moscatel vine-shoot extracts as a grapevine biostimulant to enhance wine quality. Food Res. Int. 2017, 98, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliordos, D.-E.; Alatzas, A.; Kontoudakis, N.; Unlubayir, M.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Lanoue, A.; Kotseridis, Y. Benzothiadiazole affects grape polyphenol metabolism and wine quality in two greek cultivars: Effects during ripening period over two years. Plants 2023, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Tinti, A.; Nardi, S. Biological activity of vegetal extracts containing phenols on plant metabolism. Molecules 2016, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.R.; Antoniolli, A.; Bottini, R. Extraction, characterization and utilisation of bioactive compounds from wine industry waste. In Utilisation of Bioactive Compounds from Agricultural and Food Waste; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 213–229. ISBN 9781315151540. [Google Scholar]

- Goufo, P.; Singh, R.K.; Cortez, I. A reference list of phenolic compounds (including stilbenes) in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) roots, woods, canes, stems, and leaves. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perra, M.; Bacchetta, G.; Muntoni, A.; De Gioannis, G.; Castangia, I.; Rajha, H.N.; Manca, M.L.; Manconi, M. An outlook on modern and sustainable approaches to the management of grape pomace by integrating green processes, biotechnologies and advanced biomedical approaches. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 98, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, S.; Bottini, R.; Fontana, A. Background and perspectives on the utilization of canes’ and bunch stems’ residues from the wine industry as sources of bioactive phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8699–8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralbo-Molina, A.; Luque de Castro, M.D. Potential of residues from the Mediterranean agriculture and agrifood industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 32, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souquet, J.M.; Labarbe, B.; Le Guerneve, C.; Cheynier, V.; Moutounet, M. Phenolic composition of grape stems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, Z.; Guerrero, R.F.; Fernández-Marin, M.I.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Palma, M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of stilbenoids from grape stems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12549–12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, I.; Moler, J.A.; Arteta, M.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Phenolic composition of grape stems from different spanish varieties and vintages. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, G.; Sagdic, O.; Baydar, N.G.; Kurumahmutoglu, Z. Antibacterial activities and total phenolic contents of grape pomace extracts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1807–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, C.M.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Pinho, S.P.; Ferreira, I.S.C. Grape pomace as a source of phenolic compounds and diverse bioactive properties. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordiga, M.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M. Valorisation of grape pomace: An approach that is increasingly reaching its maturity–A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Han, Y.; Tian, X.; Sajid, M.; Mehmood, S.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Phenolic composition of grape pomace and its metabolism. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 4865–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijing, Y.; Shavandi, A.; Harrison, R.; Bekhit, A.E.A. Characterization of phenolic compounds in wine lees. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Palacios, M.J. Wine lees as a source of antioxidant compounds. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, M.; Restuccia, D.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Crupi, P.; Ioele, G.; Gorelli, B.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Saponara, S.; Aiello, F. Wine lees as source of antioxidant molecules: Green extraction procedure and biological activity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Dahuja, A.; Tiwari, S.; Punia, S.; Tak, Y.; Amarowic, R.; Bhoite, A.G.; Singh, S.; Joshi, S.; Panesar, P.S.; et al. Recent trends in extraction of plant bioactives using green technologies: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 353, 129431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-García, A.I.; Martínez-Gil, A.M.; Cadahía, E.; Pardo, F.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Oak extract application to grapevines as a plant biostimulant to increase wine polyphenols. Food Res. Int. 2014, 55, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, A.M.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Martínez, L.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Effect of oak extract application to Verdejo grapevines on grape and wine aroma. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3253–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gómez, R.; Zalacain, A.; Pardo, F.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. An innovative use of vine-shoots residues and their “feedback” effect on wine quality. Inn. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glories, Y.; Agustin, M. Maturité phénolique du raisin, conséquences technologiques: Application aux millésimes 1991 et 1992. In Proceedings of the Colloque Journée Technique du CIVB, Bordeaux, France, 21 January 1993; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Puertas, B.; Guerrero, R.F.; Jurado, M.S.; Jimenez, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Evaluation of alternative winemaking processes for red wine color enhancement. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2008, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo, B.; Lopez-Infante, M.I.; Ramirez-Perez, P.; Gonzalez-Miret, M.L.; Heredia, F.J. Influence of prefermentative cold maceration on the color and anthocyanic copigmentation of organic Tempranillo wines elaborated in a warm climate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6797–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasanta, C.; Caro, I.; Gómez, J.; Pérez, L. The influence of ripeness grade on the composition of musts and wines from Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo grown in a warm climate. Food Res. 2014, 64, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis; OIV: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ribereau-Gayon, P.; Glories, Y.; Maujean, A.; Dubourdieu, D. Phenolic compounds. In Handbook of Enology 2nd Volume, The Chemistry of Wine: Stabilization and Treatments; John Willey & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006; pp. 129–186. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6564:1985; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Flavour Profile Methods. International Organisation for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985.

- Yang, J.; Martinson, T.E.; Liu, R.H. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activities of wine grapes. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutter, D. Chemical-reaction detection of catechins and proanthocyanidins with 4 dimethylaminocinnamaldehyde. J. Chrom. A 1989, 467, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.J.; Papageorgiou, A.E.; Setati, M.E.; Blancquaert, E.H. Effects of Ecklonia maxima seaweed extract on the fruit, wine—Quality and microbiota in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. S. Afr. J. Bot 2024, 172, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasanta, C.; Cejudo, C.; Gómez, J.; Caro, I. Influence of prefermentative cold maceration on the chemical and sensory properties of red wines produced in warm climates. Processes 2023, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comuzzo, P.; Battistutta, F. Chapter 2—Acidification and pH control in red wines. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 17–34. ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Bibbins, B.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Salgado, J.M.; Pinheiro de Souza Oliveira, R.; Domínguez, J.M. Potential of lees from wine, beer and cider manufacturing as a source of economic nutrients: An overview. Waste Manag. 2015, 40, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Baran, Y.; Navascués, E.; Santos, A.; Calderón, F.; Marquina, D.; Rauhut, D.; Benito, S. Biological management of acidity in wine industry: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 375, 109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasanta, C.; Gómez, J. Tartrate stabilization of wines. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 28, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerm, E.; Engelbrecht, L.; du Toit, M. Malolactic fermentation: The ABC’s of MLF. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 31, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, B.; Jimenez, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E.; Piñeiro, Z. Effect of the dry ice maceration and oak cask fermentation on colour parameters and sensorial evaluation of Tempranillo wines. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portu, J.; Rosa Gutiérrez-Viguera, A.; González-Arenzana, L.; Santamaría, P. Characterization of the color parameters and monomeric phenolic composition of ‘Tempranillo’ and ‘Graciano’ wines made by carbonic maceration. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 134327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Sánchez, M.; Castro, R.; Rodríguez-Dodero, M.C.; Durán-Guerrero, E. The impact of ultrasound, micro-oxygenation and oak wood type on the phenolic and volatile composition of a Tempranillo red wine. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol. 2022, 163, 113618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; García-Estévez, I. Chapter 13—Wine color evolution and stability. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 195–204. ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.; de Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. Chapter 14—Polymeric pigments in red wines. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 207–218. ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5. [Google Scholar]

- Echave, J.; Barral, M.; Fraga-Corra, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gándara, J. Bottle aging and storage of wines: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chira, K.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.L. Cabernet sauvignon red wine astringency quality control by tannin characterization and polymerization during storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 234, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Pueyo, E.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Potential of phenolic compounds for controlling lactic acid bacteria growth in wine. Food Control 2008, 19, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcrand, H.; Duenas, M.; Salas, E.; Cheynier, V. Phenolic reactions during winemaking and aging. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagas, M.; Núñez, V.; Bartolomé, B.; Gómez-Cordovés, C. Anthocyanin-derived pigments in Graciano, Tempranillo, and Cabernet Sauvignon wines produced in Spain. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagas, M.; Gómez-Cordovés, C.; Bartolomé, B. Evolution of the phenolic content of red wines from Vitis vinifera L. during ageing in bottle. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Xie, K.; Liao, X.; Tan, J. Factors affecting the stability of anthocyanins and strategies for improving their stability: A review. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monagas, M.; Martin-Alvarez, P.J.; Bartolome, B.; Gomez-Cordoves, C. Statistical interpretation of the color parameters of red wines in function of their phenolic composition during ageing in bottle. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, R. The copigmentation of anthocyanins and its role in the color of red wine: A critical review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2001, 52, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine polyphenol content and its influence on wine quality and properties: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casassa, L.F.; Harbertson, J.F. Extraction, evolution, and sensory impact of phenolic compounds during red wine maceration. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.A.; Melgosa, M.; Pérez, M.M.; Hita, E.; Negueruela, A.I. Visual and instrumental color evaluation in red wines. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2001, 7, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | GS | GP | WL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic content * | 50.0 ± 5.7 b | 315.6 ± 14.9 a | 23.2 ± 2.0 b |

| Total flavanols ** | 37.1 ± 4.2 b | 131.8 ± 12.6 a | 14.3 ± 1.1 b |

| Total flavonoids ** | 46.2 ± 5.9 b | 165.3 ± 9.6 a | 18.7 ± 0.9 c |

| Total anthocyanins *** | 0.9 ± 0.2 b | 65.4 ± 7.7 a | 2.0 ± 0.4 b |

| Parameter | CT | GS | GP | WL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (kg/plant) | 6.05 ± 0.72 | 5.92 ± 1.02 | 5.82 ± 1.01 | 5.89 ± 1.02 |

| Baumé degree | 12.6 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.3 | 12.5 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 0.3 |

| Total acidity (g/L tartaric acid) | 4.20 a ± 0.09 | 3.91 b ± 0.11 | 4.19 a ± 0.10 | 4.30 a ± 0.13 |

| pH | 3.38 ± 0.02 | 3.40 ± 0.07 | 3.36 ± 0.03 | 3.40 ± 0.07 |

| Sugar/total acidity index | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2 |

| CT | GS | GP | WL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressing stage | ||||

| Total acidity (g/L tartaric acid) | 6.29 a ± 0.10 | 5.89 b ± 0.02 | 6.01 ab ± 0.03 | 5.90 b ± 0.02 |

| pH | 3.77 ± 0.03 | 3.83 ± 0.02 | 3.76 ± 0.02 | 3.83 ± 0.04 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 2.34 ± 0.21 | 2.31 ± 0.14 | 2.25 ± 0.29 | 2.21 ± 0.17 |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 2.71 ± 0.23 | 2.53 ± 0.12 | 2.63 ± 0.08 | 2.65 ± 0.05 |

| Potassium (mg/L) | 1561 a ± 15 | 1470 b ± 52 | 1586 a ± 29 | 1761 c ± 52 |

| Bottling stage | ||||

| Ethanol (% v/v) | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 13.0 ± 0.3 |

| Total acidity (g/L tartaric acid) | 5.44 ± 0.08 | 5.43 ± 0.03 | 5.37 ± 0.05 | 5.49 ± 0.11 |

| pH | 3.67 ± 0.02 | 3.65 ± 0.01 | 3.64 ± 0.02 | 3.66 ± 0.01 |

| Volatile acidity (g/L acetic acid) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.39 ± 0.11 |

| Glycerine (g/L) | 8.26 ± 0.17 | 8.51 ± 0.23 | 8.11 ± 0.19 | 7.72 ± 0.29 |

| Reducing sugars (g/L) | 2.04 ± 0.252 | 2.04 ± 0.17 | 1.90 ± 0.16 | 2.38 ± 0.15 |

| Acetic acid (g/L) | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 1.21 ± 0.08 | 1.24 ± 0.14 | 1.24 ± 0.17 | 1.11 ± 0.19 |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| Lactic acid (g/L) | 2.02 ± 0.11 | 1.83 ± 0.07 | 1.99 ± 0.14 | 1.88 ± 0.16 |

| Succinic acid (g/L) | 1.46 ± 0.09 | 1.43 ± 0.13 | 1.41 ± 0.11 | 1.21 ± 0.15 |

| CT | GS | GP | WL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholic fermentation onset | ||||

| TPI | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 11.3 ± 0.1 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 34 ± 2 | 35 ± 2 | 28 ± 3 | 39 ± 4 |

| Tannins (g/L) | 0.68 a ± 0.09 | 0.88 b ± 0.04 | 0.76 b ± 0.11 | 0.96 b ± 0.15 |

| Pressing | ||||

| TPI | 47.1 ± 3.7 | 48.4 ± 2.9 | 46.2 ± 2.5 | 53.4 ± 3.8 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 413 ab ± 3 | 454 a ± 7 | 388 b ± 4 | 449 a ± 6 |

| Tannins (g/L) | 3.84 ± 0.18 | 4.09 ± 0.25 | 3.86 ± 0.39 | 4.36 ± 0.47 |

| After malolactic fermentation | ||||

| TPI | 42.8 a ± 2.4 | 49.4 b ± 2.1 | 43.9 a ± 1.2 | 49.7 b ± 1.6 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 375 ab ± 5 | 417 b ± 4 | 340 a ± 5 | 389 b ± 7 |

| Tannins (g/L) | 3.85 ab ± 0.10 | 4.17 b ± 0.19 | 3.72 a ± 0.11 | 4.21 b ± 0.13 |

| Bottling | ||||

| TPI | 42.9 a ± 1.1 | 51.2 b ± 2.8 | 42.0 a ± 1.0 | 48.9 b ± 1.3 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 339 a ± 7 | 397 b ± 6 | 311 a ± 8 | 370 b ± 9 |

| Tannins (g/L) | 3.78 a ± 0.09 | 4.34 b ± 0.21 | 3.45 a ± 0.03 | 4.09 b ± 0.21 |

| 12-month ageing | ||||

| TPI | 40.1 a ± 1.2 | 48.6 b ± 2.5 | 41.8 a ± 1.4 | 47.2 b ± 2.0 |

| Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 175 a ± 5 | 201 b ± 3 | 154 c ± 5 | 185 a ± 2 |

| Tannins (g/L) | 3.44 a ± 0.10 | 4.11 b ± 0.19 | 3.53 a ± 0.06 | 3.97 b ± 0.09 |

| Stage | Assay | Parameter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour Intensity | Hue | L* | a* | b* | C*ab | h*ab | ΔE*ab | ||

| Pressing | CT | 11.17 ± 0.72 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 57.96 ± 2.28 | 49.92 ± 2.00 | −2.57 ± 1.23 | 49.99 ± 1.22 | 357.37 ± 0.55 | - |

| GS | 11.42 ± 1.43 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 60.21 ± 1.25 | 49.22 ± 1.86 | −1.81 ± 0.88 | 50.51 ± 3.11 | 358.33 ± 1.57 | 2.48 | |

| GP | 10.75 ± 1.14 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 60.17 ± 2.01 | 47.42 ± 2.24 | −2.58 ± 1.03 | 45.96 ± 3.28 | 356.52 ± 0.99 | 3.34 | |

| WL | 11.49 ± 0.82 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 60.23 ± 1.68 | 49.64 ± 1.75 | −1.43 ± 1.11 | 50.12 ± 3.10 | 357.82 ± 0.94 | 2.54 | |

| Bottling | CT | 6.47 ab ± 0.17 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 63.86 ab ± 2.27 | 40.62 ab ± 1.19 | 0.89 ab ± 0.13 | 40.63 ab ± 1.22 | 1.26 ab ± 0.28 | - |

| GS | 8.02 a ± 0.25 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 56.33 a ± 1.16 | 48.54 a ± 1.91 | 2.03 a ± 0.65 | 48.58 a ± 2.56 | 2.39 b ± 0.55 | 10.99 | |

| GP | 5.52 b ± 0.13 | 0.67 ± 0.09 | 68.64 b ± 2.91 | 36.01 b ± 1.82 | 0.11 b ± 0.09 | 36.02 b ± 1.79 | 0.77 a ± 0.16 | 6.69 | |

| WL | 7.55 a ± 0.16 | 0.63 ± 0.15 | 56.51 a ± 1.02 | 48.45 a ± 2.31 | 2.06 a ± 0.50 | 48.49 a ± 2.06 | 2.43 b ± 0.67 | 10.80 | |

| 12 months ageing | CT | 8.45 ab ± 0.11 | 0.67 a ± 0.01 | 57.19 ab ± 1.38 | 40.27 ab ± 0.46 | 4.35 a ± 0.33 | 40.50 ab ± 0.35 | 6.19 a ± 1.02 | - |

| GS | 9.75 b ± 0.19 | 0.68 a ± 0.00 | 54.40 a ± 1.77 | 41.67 b ± 0.31 | 7.40 b ± 0.65 | 42.32 b ± 0.88 | 10.11 b ± 0.65 | 7.62 | |

| GP | 7.58 a ± 0.14 | 0.71 b ± 0.00 | 61.60 b ± 1.30 | 36.41 a ± 0.64 | 5.35 a ± 0.58 | 36.81 a ± 0.40 | 8.38 ab ± 0.53 | 4.23 | |

| WL | 8.77 ab ± 0.10 | 0.72 b ± 0.01 | 56.90 ab ± 2.55 | 39.79 ab ± 0.42 | 6.94 b ± 0.25 | 40.39 ab ± 0.27 | 9.88 b ± 0.55 | 7.39 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piñeiro, Z.; Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Fernández-Marín, M.I.; Jiménez-Hierro, M.J.; Cretazzo, E.; Rodríguez-Torres, I.C. Impact of Foliar Application of Winemaking By-Product Extracts in Tempranillo Grapes Grown Under Warm Climate: First Results. Beverages 2025, 11, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11030060

Piñeiro Z, Gutiérrez-Escobar R, Aliaño-González MJ, Fernández-Marín MI, Jiménez-Hierro MJ, Cretazzo E, Rodríguez-Torres IC. Impact of Foliar Application of Winemaking By-Product Extracts in Tempranillo Grapes Grown Under Warm Climate: First Results. Beverages. 2025; 11(3):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11030060

Chicago/Turabian StylePiñeiro, Zulema, Rocío Gutiérrez-Escobar, María Jose Aliaño-González, María Isabel Fernández-Marín, María Jesús Jiménez-Hierro, Enrico Cretazzo, and Inmaculada Concepción Rodríguez-Torres. 2025. "Impact of Foliar Application of Winemaking By-Product Extracts in Tempranillo Grapes Grown Under Warm Climate: First Results" Beverages 11, no. 3: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11030060

APA StylePiñeiro, Z., Gutiérrez-Escobar, R., Aliaño-González, M. J., Fernández-Marín, M. I., Jiménez-Hierro, M. J., Cretazzo, E., & Rodríguez-Torres, I. C. (2025). Impact of Foliar Application of Winemaking By-Product Extracts in Tempranillo Grapes Grown Under Warm Climate: First Results. Beverages, 11(3), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11030060