4. Results

A total of 398 patients participated in this study, aged 4.11 to 29.11, and divided in three groups: patients with strabismus (PS), refractive amblyopia (PRA), and healthy controls (HCs).

HCs: There were 142 patients in total, 90 male (63.4%) and 52 female (36.6%); the mean age was 9.72 ± 4.74. Of the patients, 19 of them presented with esophoria (13.38%) and 112 had exophoria (78.87%).

Only 13 patients were myopic (9.15%), while 106 were hyperopic (74.65%) (with or without astigmatism); 22 patients did not present any refractive error (15.49%) and only one patient had pure astigmatism (0.71%). Here, 122 patients (85.9%) had right eye motor ocular dominance.

PRA: There were 109 patients in total, 58 male (53.21%) and 51 female (46.79%); the mean age was 9.13 ± 5.26. Here, 15 of them had esophoria (13.76%) and 76 presented with exophoria (69.72%).

Additionally, 17 patients had myopia (15.6%) and 87 presented with hyperopia (79.82%) (with or without astigmatism); five were pure astigmatisms (4.58%). There were 94 patients (86.2%) with right eye motor ocular dominance. All patients presented with stereopsis.

PS: There were 147 patients in total, 80 male (54.42%) and 67 female (45.58%); the mean age was 10.61 ± 6.36. Here, there were 52 patients with ET (35.37%), 89 with XT (60.54%), and six with pure HT (4.09%). Additionally, hypertropia was seen in 16 other patients as a secondary deviation (mean 5.56 ± 4.8 at far and 5.58 ± 5.34 at near, respectively). A total of 53 patients were stereoblind (36%), 94 presented with stereopsis (64%), and 66 patients had amblyopia (44.9%). A total of 111 patients (75.5%) had right eye motor ocular dominance. Furthermore, 27 patients had myopia (18.37%) and 88 presented with hyperopia (59.86%). A total of 24 patients did not present any significative refractive error (16.33%), and eight patients had pure astigmatism (5.44%). It is important to mention that the mean value for PS with stereopsis was (125.81 ± 175.83, N = 94). The mean values and SD of all variables measured in this study are presented in

Table 1.

One way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparison was used to analyze most of the variables presented in

Table 1, as (N > 30) for each group.

Kruskal–Wallis, on the other hand, was used to analyze the state of myopia.

An independent samples t-test (N > 30) was used to analyze the exophoria state at near between PRA and HCs.

The Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze the phoria state between PRA and HCs when N < 30, such as exophoria at far and esophoria (far and near, respectively).

The results were gathered in two categories:

- 1

Statistically significant differences among groups

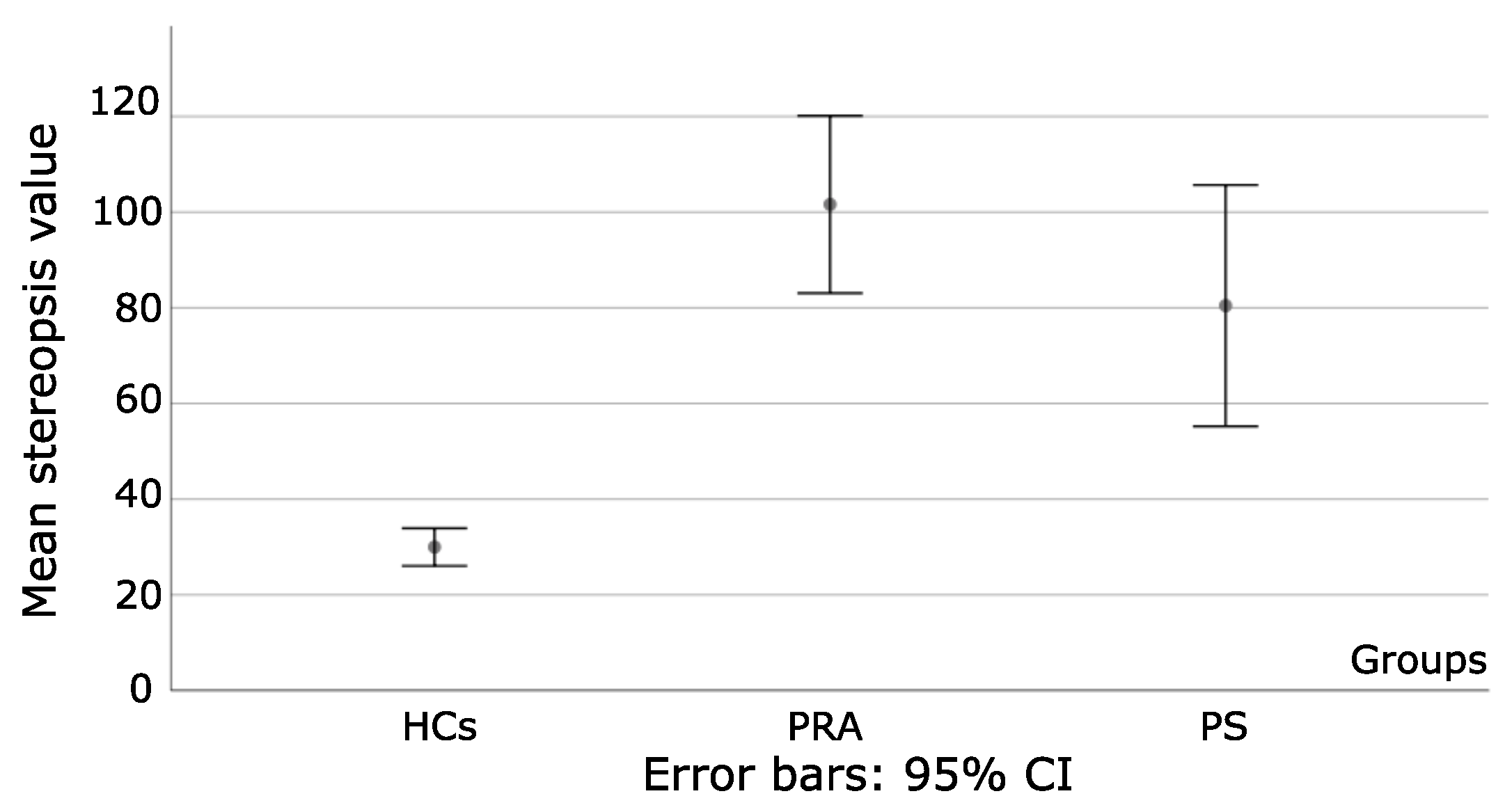

One way ANOVA was used to analyze differences on the degree of stereopsis among the three groups, where differences were statistically significant: F = 25.64 and p < 0.001.

More specifically,

p < 0.001 when HCs were compared to PA and PS, as seen in

Figure 2.

Differences between PRA and PS were statistically insignificant (p = 0.25). For PS, stereoblind patients were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, as reflected by the Std, the degree of stereopsis fluctuates widely within subjects in PS, which reflects a deeper imbalance in the sensory system than in PRA.

Additionally, for a second step, emphasis was given on PS and PRA. Patients who did not perceive stereopsis through the Random Test 2 were excluded. A total of 88 PS (mean 90.07 ± 92.79) and 109 PRA (101.61 ± 96.83) had stereopsis with the Random-Dot 2 test. The independent sample t-test was used to compare differences on the amount of stereopsis between groups, with no statistically significant difference between them; t = −0.85 and p = 0.39. To conclude, the degree of stereopsis measured with Random Dot 2 in PS and PRA is similar.

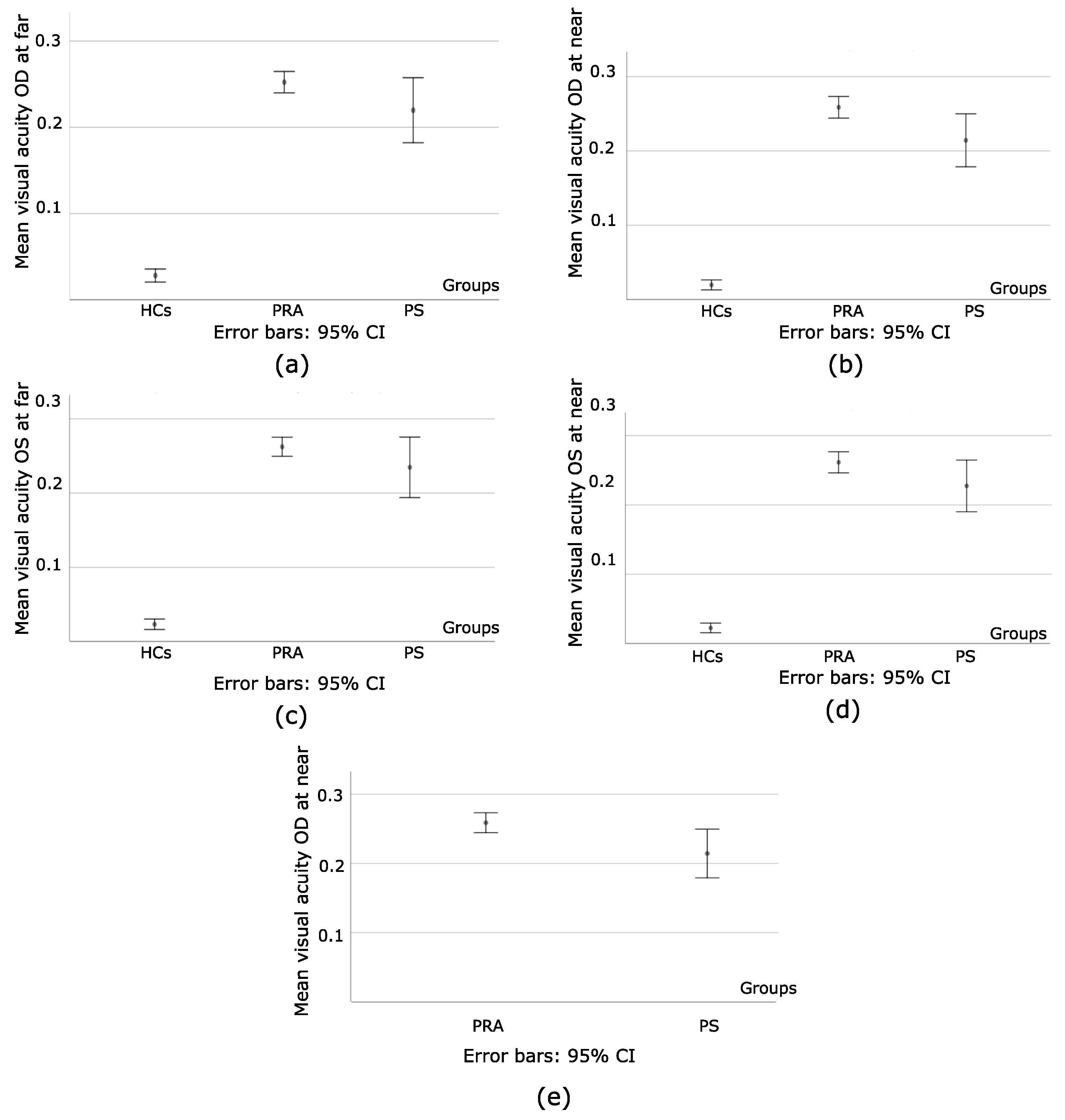

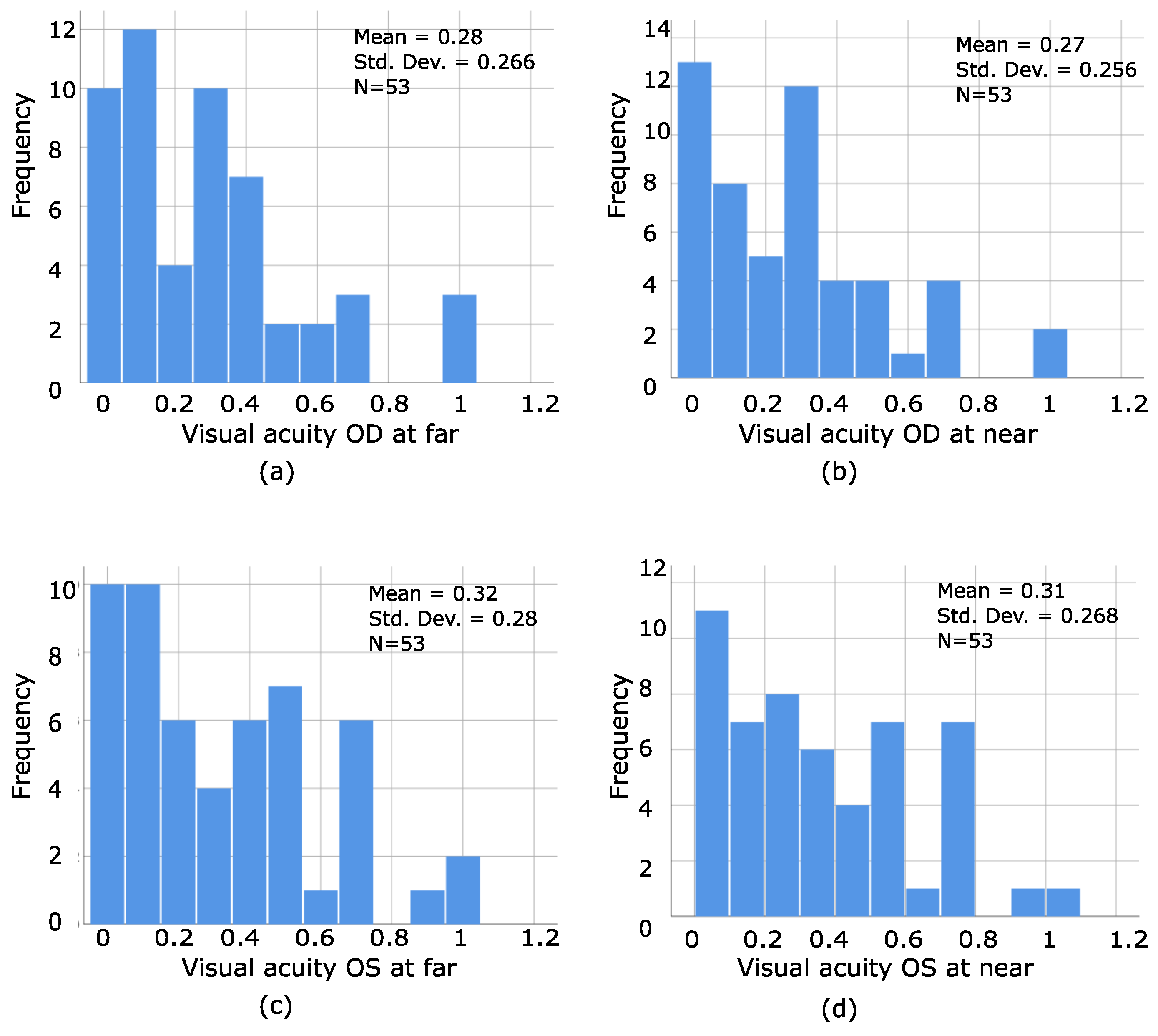

The next variable to be analyzed was visual acuity. The results of the one way ANOVA for the visual acuity of the right and left eye at far and near among the groups were as follows:

When the HCs were compared to PRA and PS, for OD, F = 92.71 at far, and F = 110.38 at near, with

p < 0.001, as seen in

Figure 3a,b. For OS, F = 91.93 at far, and F = 102.85 at near, with

p < 0.001, as seen in

Figure 3c,d. However, when PRA and PS were compared, at far,

p = 0.18 (OD) and

p = 0.35 (OS) while at near,

p = 0.03 (OD) and

p = 0.16 (OS), as seen in

Figure 3e. To summarize, HCs had a better visual acuity for both eyes at both distances, whereas statistically significant differences between PRA and PS were only found on the amount of visual acuity of the right eye at near distance.

An independent Sample

t-Test was used to compare the means of binocular visual acuity at far (BVAF) and binocular visual acuity at near (BVAN) between PRA and PS. Statistically significant differences were found at far (t = −4.31 and

p < 0.001) and near (t = −2.2 with

p = 0.03), showing that PS had better binocular visual acuity (BVA) at both distances, as seen in

Figure 4a,b. Once more, the mean and Std values for PS indicate the heterogeneity of the values of BVAF and BVAN.

A one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was then used to analyze the refractive state (hyperopia and astigmatism) between our groups. There were statistically significant differences among the groups. For a hyperopia of OD, F = 31.46, p < 0.001, whereas for OS, F = 24.79, p < 0.001. Specifically, p < 0.001 when HCs are compared to PRA and PS for both eyes, whereas when PRA and PS are compared between them for OD, p = 0.63; for OS, p = 0.93.

When it comes to the astigmatism value, statistically significant differences among groups were found for OD, F = 4.94, p = 0.008, whereas for OS, F = 3.49, p = 0.03. More specifically, for OD, differences were found between HCs vs. PS, p = 0.01; and HCs vs. PRA, p = 0.02. When PRA was compared to PS, the analysis showed a p = 0.9. For OS, HCs vs. PRA, p = 0.03; HCs vs. PS, p = 0.14; PA vs. PS, p = 0.67. As it can be seen, the differences are more related to the right eye, being this the dominant one for most of our participants.

The Kruskal–Wallis and the Bonferroni post hoc tests for multiple comparison were used to analyze differences in the mean value of myopia, considering that N < 30 for each group, with no statistically significant differences between the groups. Specifically, H = 0.02, p = 0.9 for OD, whereas H = 0.43, p = 0.51 for OS.

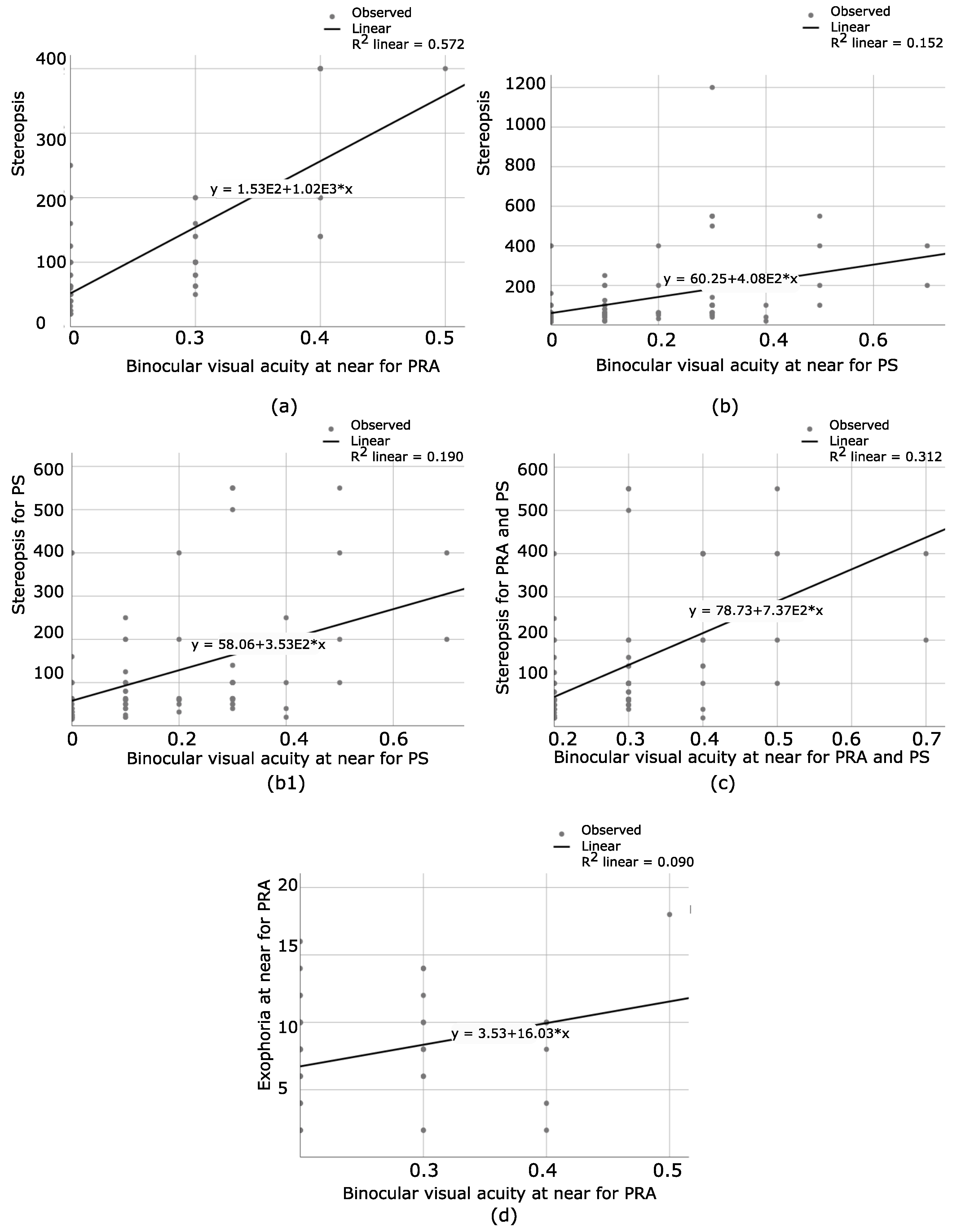

Multiple regression and correlation analysis was also used to analyze the relationship between stereopsis and the amount of binocular visual acuity at far and near for PS and PRA. Binocular visual acuity was considered for this analysis, as the stereopsis test is performed in a binocular state.

Table 2 illustrates our findings.

For PRA, a positive correlation was found between stereopsis and the binocular visual acuity (BVA) (R2 = 0.57, F (2,106) = 74.95

p < 0.001). However, BVAF was not a unique predictor (

= 208.84,

p = 0.06), but BVAN was a unique one (

= 999.28,

p < 0.001), as shown at

Figure 5a. Then, for PS, the relationship between BVA (far and near) and stereopsis (only patients with a certain degree of stereopsis were included) was analyzed. A positive correlation was found in this case, R2 = 0.15, F (2,91) = 9.49,

p < 0.001. However, visual acuity at near was the unique predictor, (

= 278.82,

p = 0.04), while visual acuity at far was not such a predictor (

= 197.64,

p = 0.14), as seen in

Figure 5b. Considering that there was only one patient with a gross stereopsis of 1200″, it was excluded from the analysis and R2 = 0.19, F (2,90) = 12.1,

p < 0.001. Once again, binocular visual acuity at near was the unique predictor for stereopsis,

= 251.4, t = 2.52,

p = 0.01, as seen in

Figure 5(b1). Additionally, only PS with amblyopia and stereopsis and PRA were gathered, and the relationship between stereopsis and BVA was analyzed. The patient with gross stereopsis of 1200″ was excluded. There was a positive correlation between amblyopia and stereopsis, R2 = 0.31, F (2,144) = 65.60,

p < 0.001. Once again, visual acuity at near was the unique predictor, (

= 737.48,

p < 0.001). BVAF was not such a predictor (

= 244.58,

p = 0.08), as seen in

Figure 5c. To conclude, only visual acuity at near is a predictor for the degree of stereopsis.

For PRA, another step was taken, and the relationship between the amount of BVAN and the amount of exophoria at near was analyzed. The results showed a positive correlation (R2 = 0.09, F (1,71) = 7.06 and

p = 0.01), as seen in

Figure 5d. There is a weak correlation in this case, where

= 16.03, t = 2.66 and

p = 0.01. Patients with EF were excluded, considering that only a small percentage of our population had EF. Likewise, exophoria at far was not considered for this analysis, as only a few patients presented with this condition.

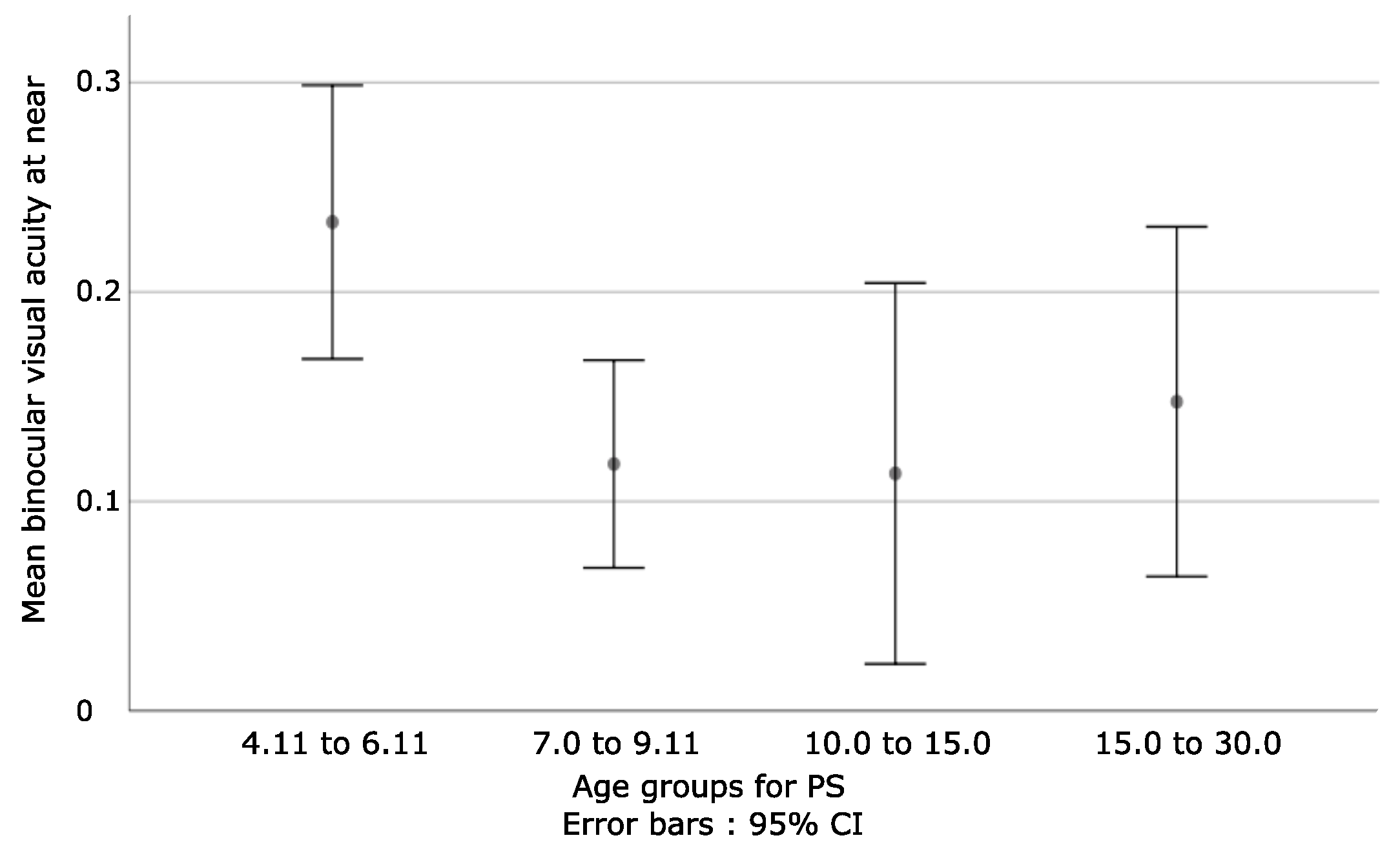

Additionally, the amount of visual acuity at far and near was analyzed based on age.

When PRA and PS with amblyopia were gathered (N = 197), the one way ANOVA analysis showed no statistically differences between groups, F = 1.23/0.34 and p = 0.3/0.8 at far and near, respectively. Then, PS and PRA were analyzed separately.

For PRA, the Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant changes between age groups, with H = 0.29 and p = 0.96 at far, while H = 3.46 and p = 0.33 at near.

For PS (N = 147), a one way ANOVA analysis showed insignificant statistical differences between age groups; F = 2.5 and p = 0.06 at far, while F = 1.17 and p = 0.32 at near.

For PS with stereopsis (N = 94), the Kruskal–Wallis test showed statistically significant differences between groups only at near, where H = 9.22 and

p = 0.03, while at far, H = 5.23 and

p = 0.16. Refer to

Table 3 for more details. A negative relationship was found when the first group was compared to the other three.

In detail, when the visual acuity at near distance was analyzed for PS and stereopsis, the Mann–Whitney test (N < 30 for each group) showed the below results:

Z = −2.65 and p = 0.008 when the first and second groups were compared.

Z = −2.25 and p = 0.02 when the first and third groups were compared.

Z = −1.95 and p = 0.05 when the first and fourth groups were compared.

Additionally:

Z = −0.65 and p = 0.52 for second and third.

Z = −0.19 and p = 0.85 for second and fourth.

Z = −0.61 and p = 0.54 for third and fourth.

To summarize these results, it can be concluded that for PS with stereopsis, BVAN obtains lower values in younger children, as seen in

Figure 6.

- 2

Statistically insignificant but clinically important findings:

A one way ANOVA showed no age differences between groups, F = 2.35 and p = 0.1.

An independent T-sample test showed no age differences between male and female participants, t = −1.51 and p = 0.13.

In PS, the magnitude of deviation (ET and XT) was correlated with the amount of visual acuity at far and near, respectively. For patients with ET, multiple regression analysis showed no such correlation; F = 0.19, p = 0.83 (both distances). Same results were seen for patients with XT, F = 0.37, p = 0.69 at far, and F = 0.1, p = 0.9 at near, respectively. Summarizing, visual acuity is not related to the phoria state or the magnitude of deviation.

An independent samples t-test was used to analyze the degree of stereopsis based on gender for each group, with no statistically significant difference between male and female (HCs, t = 0.16, p = 0.87; PRA, t = 0.21, p = 0.98; PS, t = −0.72, p = 0.47). To summarize, gender does not relate to the degree of stereopsis.

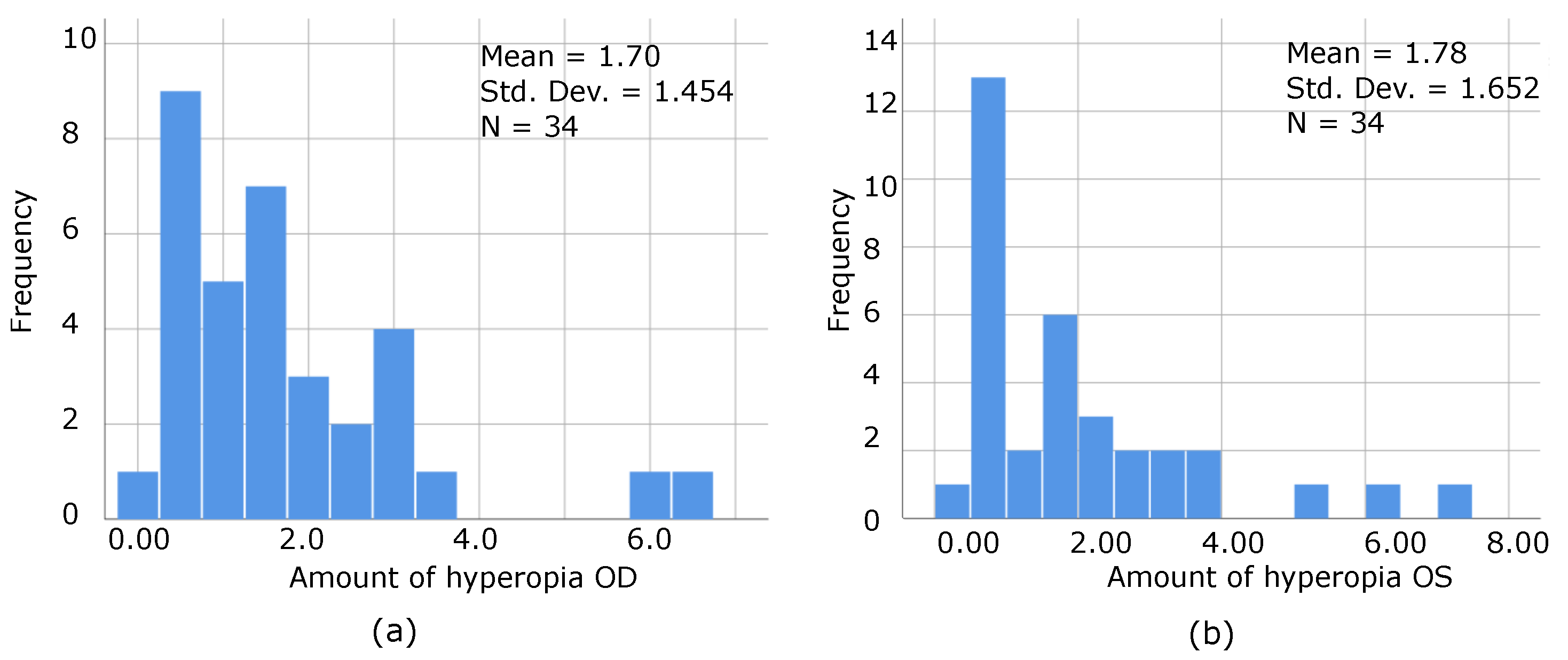

On another level, the relationship between the amount of hyperopia and stereopsis was analyzed. Considering that only a small percentage of our population was myopic, they were excluded from this analysis. From a total of 398 participants, 281 were hyperopic (70.6%) and only 57 presented myopia (14.3%). Multiple regression and correlation analysis showed no relationship between hyperopia and stereopsis for HCs (F = 0.11, p = 0.89), PS (F = 2.7, p = 0.07), and PRA (F = 1.13, p = 0.33). The amount of hyperopia does not affect the degree of stereopsis.

The relationship between hyperopia and exophoria at near PRA and HCs, and the magnitude/type of deviation (ET and XT) were now analyzed. Considering that few patients presented exophoria at far for HCs and PRA, they were excluded from this analysis. For HCs, hyperopia was not related to the amount of exophoria at near (F = 0.91, p = 0.4), while for PRA, F = 0.09, p = 0.92. For PS, F = 0.68, p = 0.51 for hyperopia-ET at near distance; F = 1.57, p = 0.22 for hyperopia-XT at near; F = 1.78, p = 0.18 for hyperopia-ET at far and F = 0.83, p = 0.44 for hyperopia-XT at far distance. As revealed by the statistical analysis, the amount of hyperopia does not affect the phoria state or the magnitude of deviation.

Finally, for PRA and PS (separately), the degree of stereopsis was analyzed based on age. Four groups were created; 4.11 to 6.11 (first group); 7.0 to 9.11 (second group); 10.0 to 15.0 (third group) and 15.0 to 30.0 (fourth group). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the means between groups (N = 30 only for the 4.11 to 6.11 group. N < 30 for the rest of the groups). For PRA, H = 5.72 and p = 0.13. For PS patients with stereopsis (N = 94), H = 5.99 and p = 0.11. Then, PRA (N = 109) and PS with stereopsis (N = 94) were grouped all together. Considering that N > 30 for each group, a one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc was used in this case, with F = 0.85 and p = 0.47. Age does not predict the degree of stereopsis.

The relationship between the amount of hyperopia and age groups was analyzed. No relationship was found between age and the refractive state when all patients were analyzed all together (F = 1.1, p = 0.29 for hyperopia OD; F = 2.54, p = 0.11 hyperopia OS). Refractive state does not depend on age.

The phoria states of PRA and HCs were compared. The amount of exophoria at near was compared using an independent samples t-test (N > 30), where t = −1.45 and p = 0.15.

A Mann–Whitney Test was used to analyze the phoria state between PRA and HCs when N < 30. Such was the case for exophoria at far and esophoria at far/near, respectively.

For exophoria at far, Z = −0.36 and p = 0.72.

For esophoria at far, Z = −0.45 and p = 0.65.

For esophoria at near, Z = −0.65 and p = 0.51.

The differences between the phoria states of PRA and HCs were statistically insignificant.

The degree of stereopsis was further analyzed based on the amount of exophoria at near for HCs and PRA, and the magnitude of deviation (ET and XT) for PS. Considering that very few patients presented esophoria at near, they were excluded from this analysis. Likewise, only the phoria state at near was considered, as the stereopsis test is performed at 40 cm. Pearson correlation and multiple regression analysis was used in SPSS. The Pearson correlation showed no relationship between the amount of exophoria at near and the degree of stereopsis: HCs (p = 0.16) and PRA (p = 0.84). For PS, multiple regression analysis for the far and near tropia states showed (F = 1.84, p = 0.17 for XT and F = 1.43, p = 0.27 for ET). To conclude, the amount of stereopsis was not related to the phoria state or the magnitude/type of deviation of a patient.

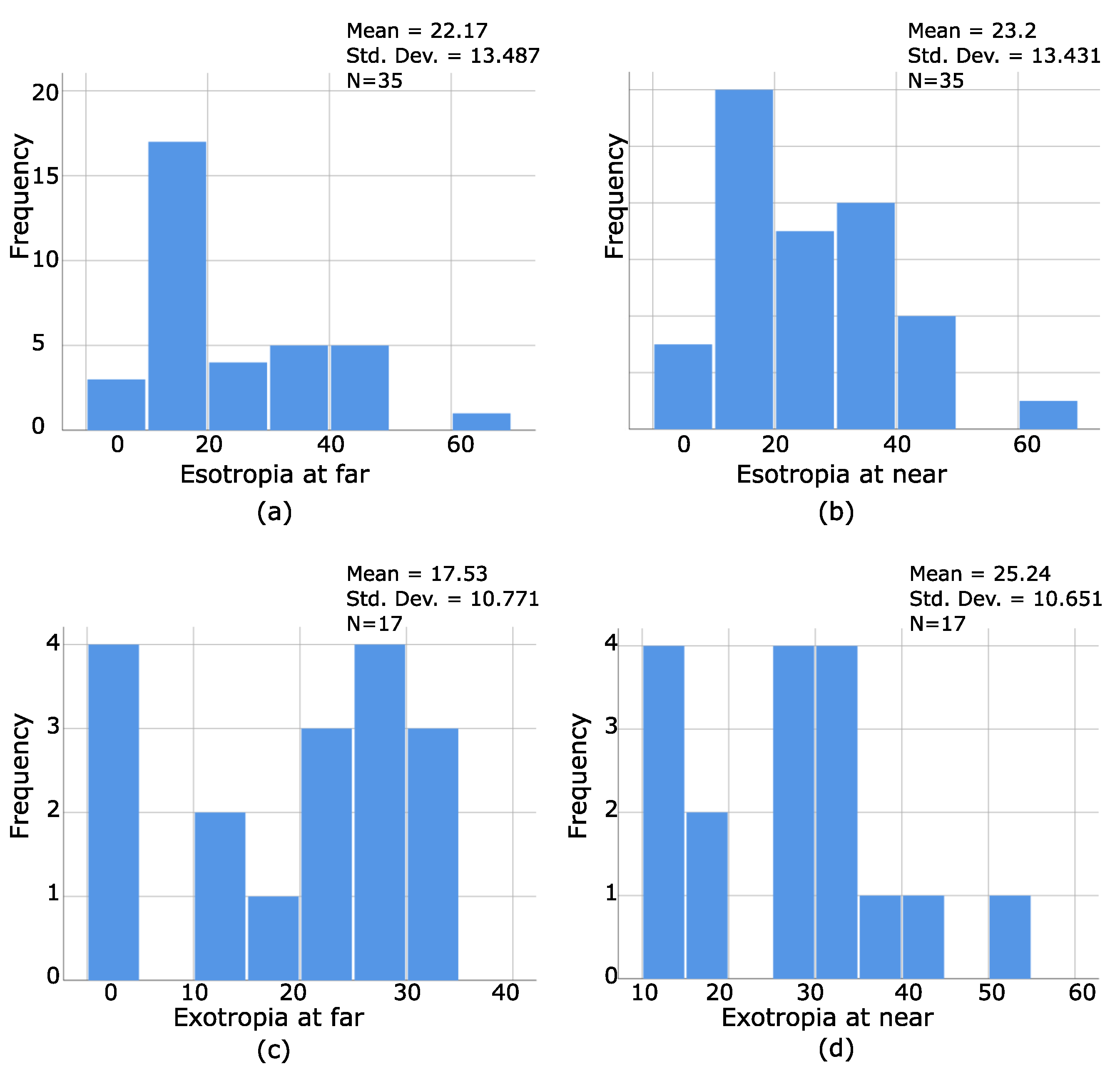

To understand the characteristics of stereoblind patients, the distribution of frequencies of the magnitudes and types of strabismus were analyzed. They were 53 stereoblind patients, 35 with ET (far and/or near), and 17 XT (far and/or near). Additionally, six patients had hypertropia as a secondary deviation, and only one had pure HT.

Figure 6a–d illustrates the results of such a distribution. As seen from

Figure 7a,b, 35 patients with ET were stereoblind, which means that ET patients have a greater tendency of being stereoblind. On the contrary, only 17 patients with XT were stereoblind, and a greater amount of deviation is necessary for patients with exotropia to be stereoblind (

Figure 7c,d). HT was not graphed as being a secondary deviation.

The distribution of the amount of visual acuity for each eye at both distances for our stereoblind population was graphically presented as well, as seen by

Figure 8a–d, where even strabismic patients without amblyopia (VA of 0.0 and 0.1 logMar) can be stereoblind, which confirms that the amount of visual acuity does not predict the presence or absence of stereopsis.

For the same group, a Pearson correlation was used to analyze the relationship between the amount of hyperopia and visual acuity at far/near, where the results were statistically insignificant. For OD, p = 0.08/0.1 while for OI, p = 0.83/0.6, respectively.

The frequency distribution of the amount of hyperopia for each eye was graphed as well, as illustrated by

Figure 9a,b, where even patients with a low degree of hyperopia can be stereoblind, as confirmed by the following graphs.

To conclude, in this research, a thorough statistical analysis was performed to see differences in the visual performances among HCs, PRA, and PS, based on the interactions among selected variables related to their best functionalities.

Table 4 represents the statistically significant differences found among them.

5. Discussion

During the past few decades, neuroimage and clinical studies have made essential progress on understanding the underlying causes of visual conditions such as amblyopia and strabismus [

22,

23], with amblyopia being an ideal model for understanding brain plasticity and its critical periods for the recovery of function [

22]. As already mentioned, there is a connection between strabismus, amblyopia, and the refractive state (such as anisometropia), and for years, researchers have been focusing on finding differences between strabismic and anisometropic amblyopes [

3,

8,

20]. However, until today, the distinctive patterns of visual loss among groups remain unclear, without any consistent functional pattern [

7]. Taking into consideration that the visual system becomes the dominant sensory modality once the child starts to explore the world around him, understanding its development and deficits becomes essential. In this paper, the new definition of amblyopia was considered [

21], as it includes all these patients with acceptable visual acuity but with symptoms of discomfort during visual performance.

In this paper, a total of 398 patients participated, divided in three groups: HCs, PRA, and PS. The visual states of patients at far and near were analyzed, and data were compared within subjects and among groups. Visual acuity, stereopsis, phoria state, magnitude, and type of strabismus, age, and gender were our variables of interests. Special interest was given to the visual performance at near, considering the visual problems associated with near work [

18].

A thorough statistical analysis was carried out for the purpose of this research. Our goal was to give live to our variables, make them interact, and find the predominate ones that can influence the visual efficacies of the participants. Therefore, the relationship between phoria state and stereopsis, magnitude/type of deviation and stereopsis, visual acuity and stereopsis, refractive state and stereopsis, age, gender and stereopsis, phoria and refractive state, and age and refractive state were explored. In the era of digital work and high technology development, the visual system becomes the main system, and its performance in different aspects of the everyday depend on its efficacity. In this paper, by analyzing the interaction among the chosen variables, we defined which ones are related to each other and we can impact on the visual performances of participants using the new definition of amblyopia for PS and PRA. This research allows us to break an old paradigm and create a new one.

The most interesting finding of this research is that binocular visual acuity at near is the unique predictor of the degree of stereopsis, in both groups, PS and PRA. This result is coherent with the way in which the degree of stereopsis with Random Dot-2 test is measured; at 40 cm and with both eyes opened. In the field of optometry, stereoacuity is an important variable that is associated with the visual performances of our patients, moreso than monocular visual acuity itself [

24,

25]. Our results confirm the theory that binocular visual acuity at near should be an important variable to be considered for the best achieved stereoacuity of a patient as one of the most essential visual skills [

26,

27], and the prescription of refractive errors should take into consideration the visual performance at near [

28], as visual acuity at far does not relate to stereoacuity. What should be highlighted here is that most visual health professionals prescribe based on the amount of visual acuity at far. As a result, patients with good visual acuity at far present discomfort at near working distance. Based on the results obtained through this research, the old way of evaluating the functionality of the visual system should be reconsidered to make the best of it.

Additionally, the heterogeneity among values obtained by PS patients confirms what the literature highlights, which is that patients with strabismus adopt to their condition as they can, making it difficult to find a common pattern among them [

6,

7,

15], a reason for why analyzing and trying to understand their visual abilities is a challenge for health professionals who are linked to the diagnosis and treatment processes of these patients. However, what makes a difference here is that stereoblind patients were only found among patients with strabismus, whereas patients with refractive amblyopia maintained a certain degree of stereopsis. Additionally, our results are consistent with what other authors have shown, which is that the type and magnitude of deviation, and the amount of visual acuity could not predict the presence or absence of stereopsis [

2].

However, what makes a difference here is that stereoblind patients were only found among patients with strabismus, whereas patients with refractive amblyopia maintained a certain degree of stereopsis. Additionally, the type and magnitude of deviation, and the amount of visual acuity could not predict the presence or absence of stereopsis, as reported in previous studies [

2].

When it comes to age groups, the only important finding of the statistical analysis was the correlation found for patients with strabismus and stereopsis. Age division was based on previous studies [

29,

30], and showed that younger children had worse visual acuity at near than older ones. It is known that the 0.0 logMar visual acuity response is not always expected in a patient younger than age 6 [

21], which could explain why younger patients do not perform the same as older ones. However, this is not the case for HCs and PRA patients, which reflects differences in the way in which the brain of PS becomes organized to adapt to the motor and sensory difficulties that are associated with strabismus.

The phoria state at near and BVAN in PRA are related to each other. This means that they can affect one another. The importance of this finding is that the amount of visual acuity and the degree of phoria at near should be considered when a patient is treated in visual therapy. Focusing on improving these two variables would improve the overall patients’ visual performance [

27].

An expected finding was the excellent visual performance of HCs when compared to PS and PRA. Specifically, they had better visual acuity for each eye at both distances, a higher degree of stereopsis, and less refractive error, without differences in the phoria state when compared to PRA, considering that an exo/esophoria is commonly found in children [

31].

In this paper, a consistent functional pattern between PS and PRA was established. BVA at near affects the degree of stereopsis, and PS had better visual acuity at both distances when compared to PRA, with more heterogeneity among the obtained values as they make personal adaptations based on their necessities to compensate for the sensorimotor imbalance of the visual system. However, we could not establish a relationship between the amount of visual acuity at far and stereoacuity [

2]. Despite all this, PS and PRA behave differently to HCs, which allow us to visualize that there is an important impact on the functionality of the visual system because of strabismus and amblyopia. We highlight here that the new definition of amblyopia was used in this research, which encompasses a larger population affected by this visual condition, a reason for why our results differ at some points from other studies. In previous papers [

7,

8,

15], the most classic and old definition of amblyopia was considered (≤20/40). However, this definition cannot explain why patients with better visual acuities than 20/40 experience a considerable number of difficulties during visual performance. Additionally, it only represents the visual acuity, as a static concept, but not the whole concept of vision, as a dynamic brain process [

21,

25,

32].

Therefore, using the new definition of amblyopia allows us to overcome these limitations and provide new data on the functionality of the visual system of patients with strabismus and amblyopia. In this paper, we focused on the interaction between selected variables and how they affect the visual performance of the participants, which makes this paper different, as literature offers few information on the interrelationship between visual skills [

25]. Likewise, for the first time, the impact of the change in the specific concept of amblyopia on the visual performance was analyzed, which open paths to more research on this topic and create new paradigms in the field of visual health care.