Tackling Imbalanced Data in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis: An Ensemble Learning Approach with Synthetic Data Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

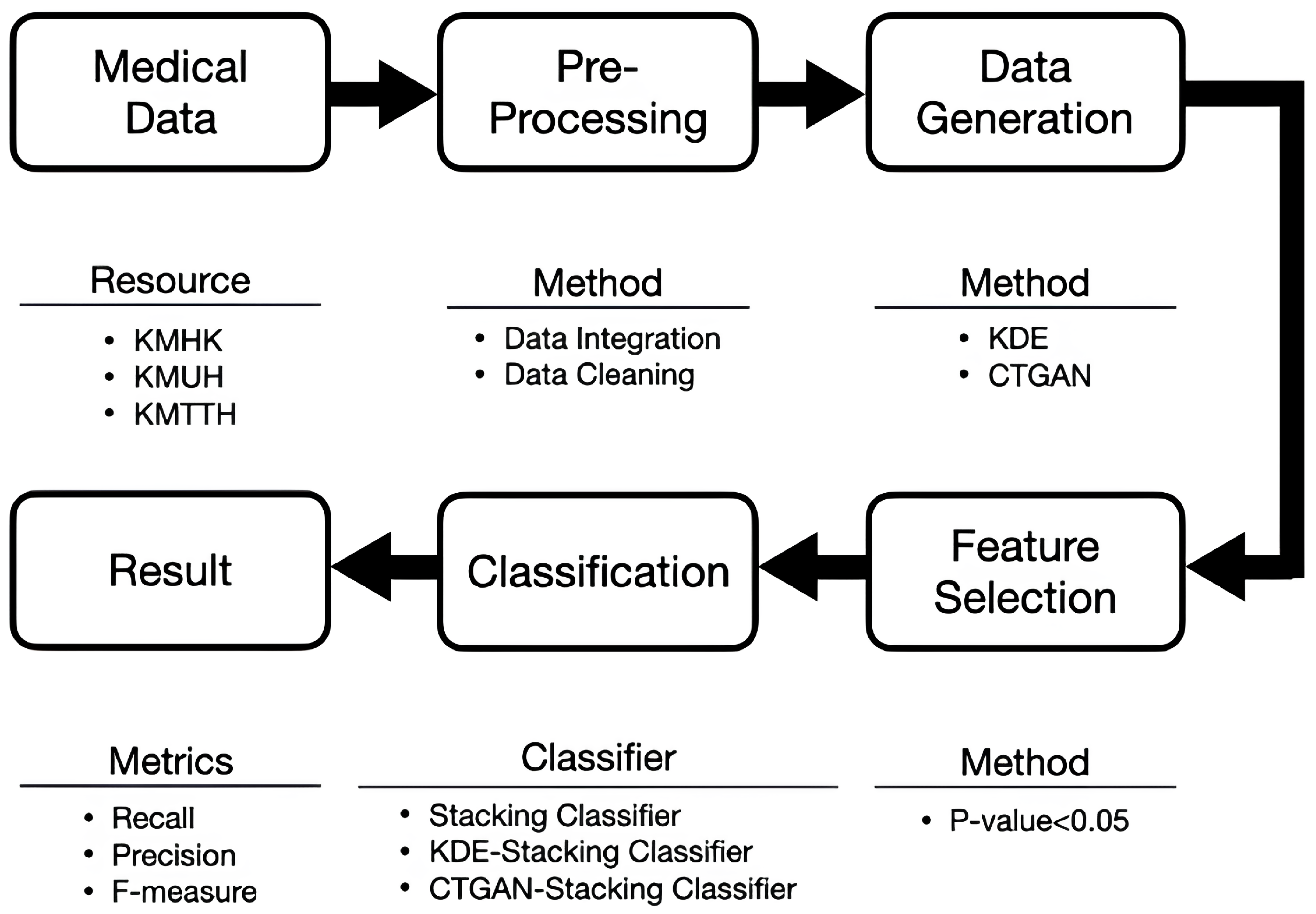

3. Architecture

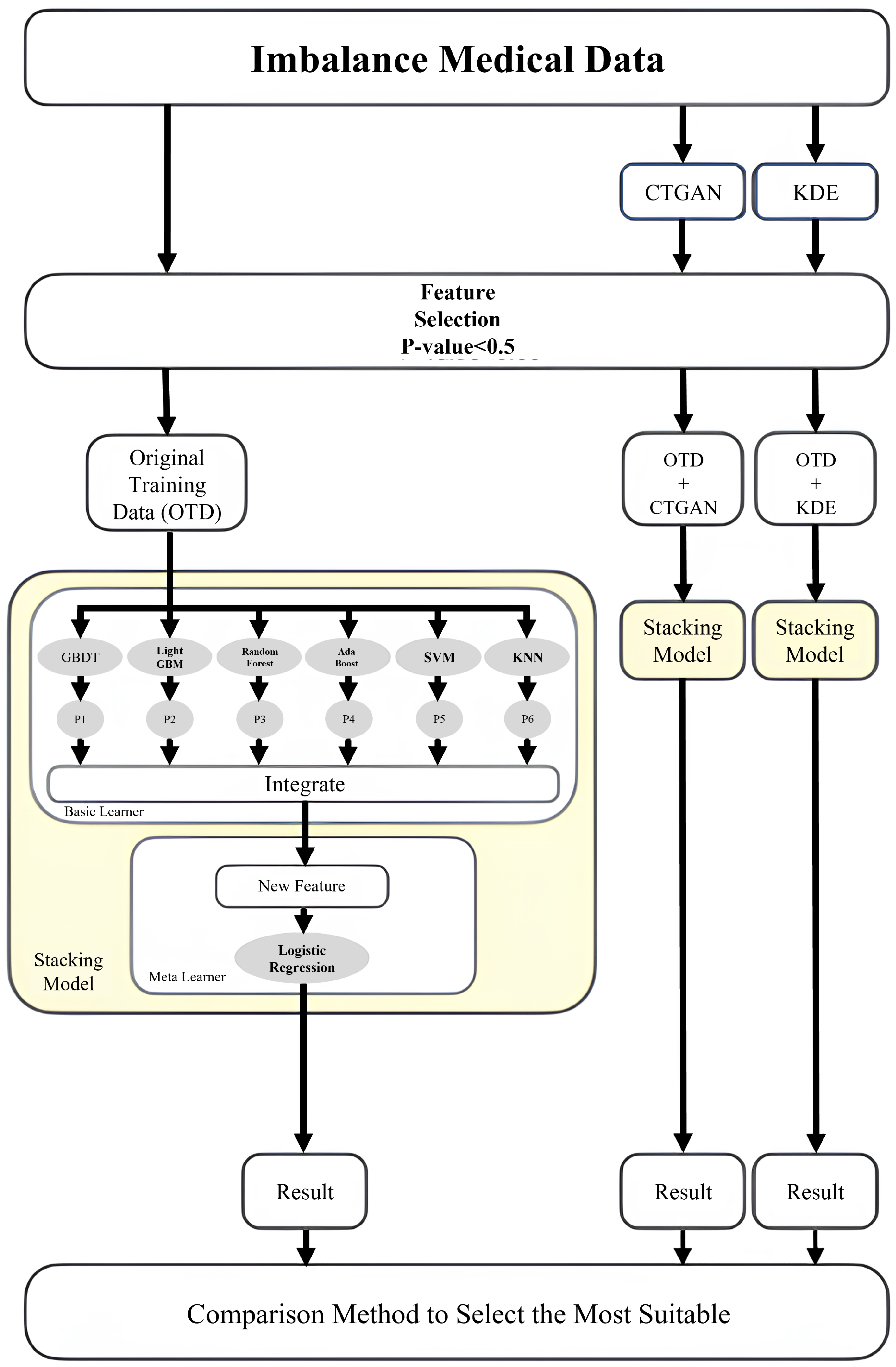

4. Method

4.1. Data Preprocessing and Data Augmentation

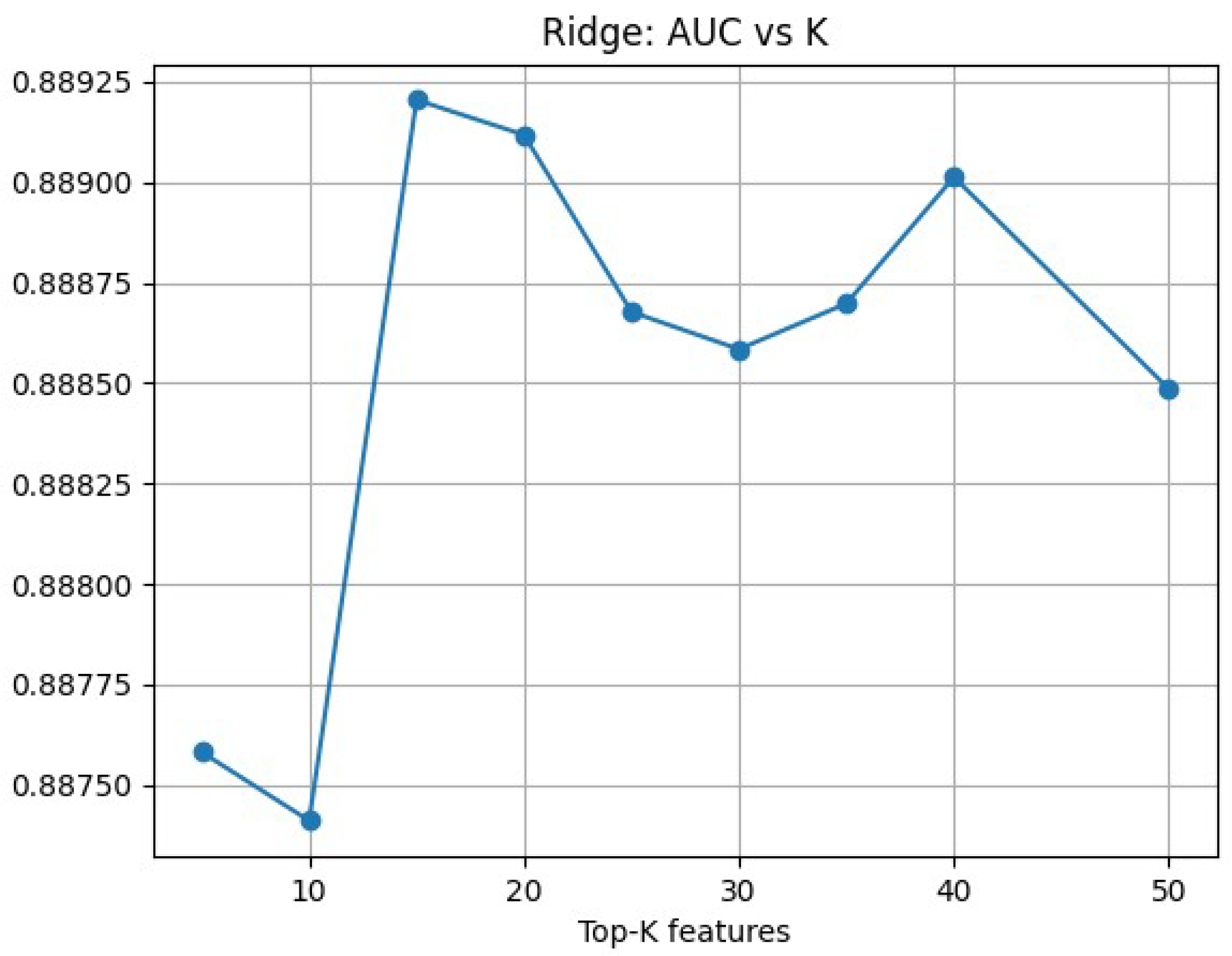

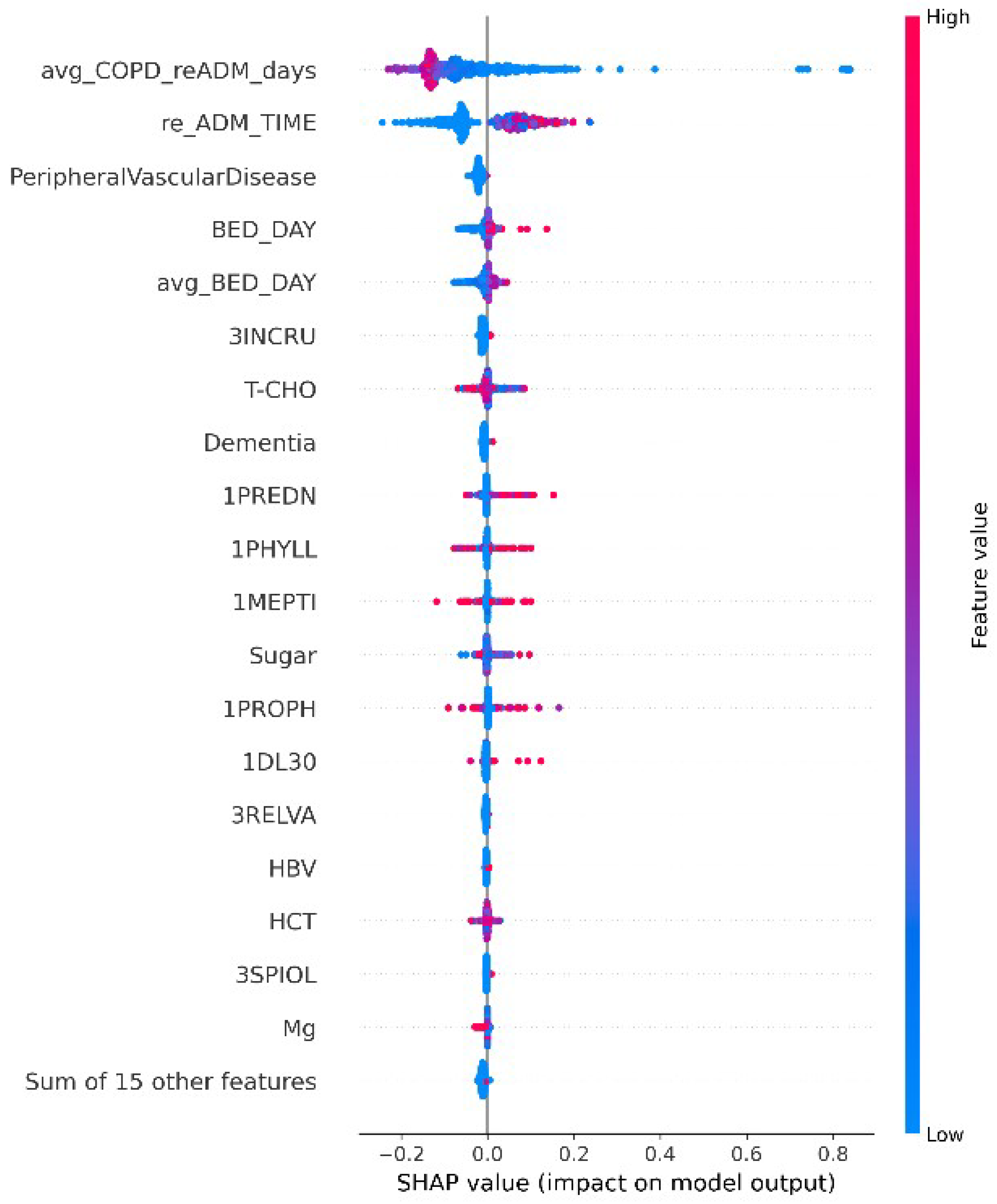

4.2. Feature Selection

4.3. Ensemble Learning Strategies

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Data Characteristics Analysis

5.2. Data Generation and Dimensionality Reduction

5.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

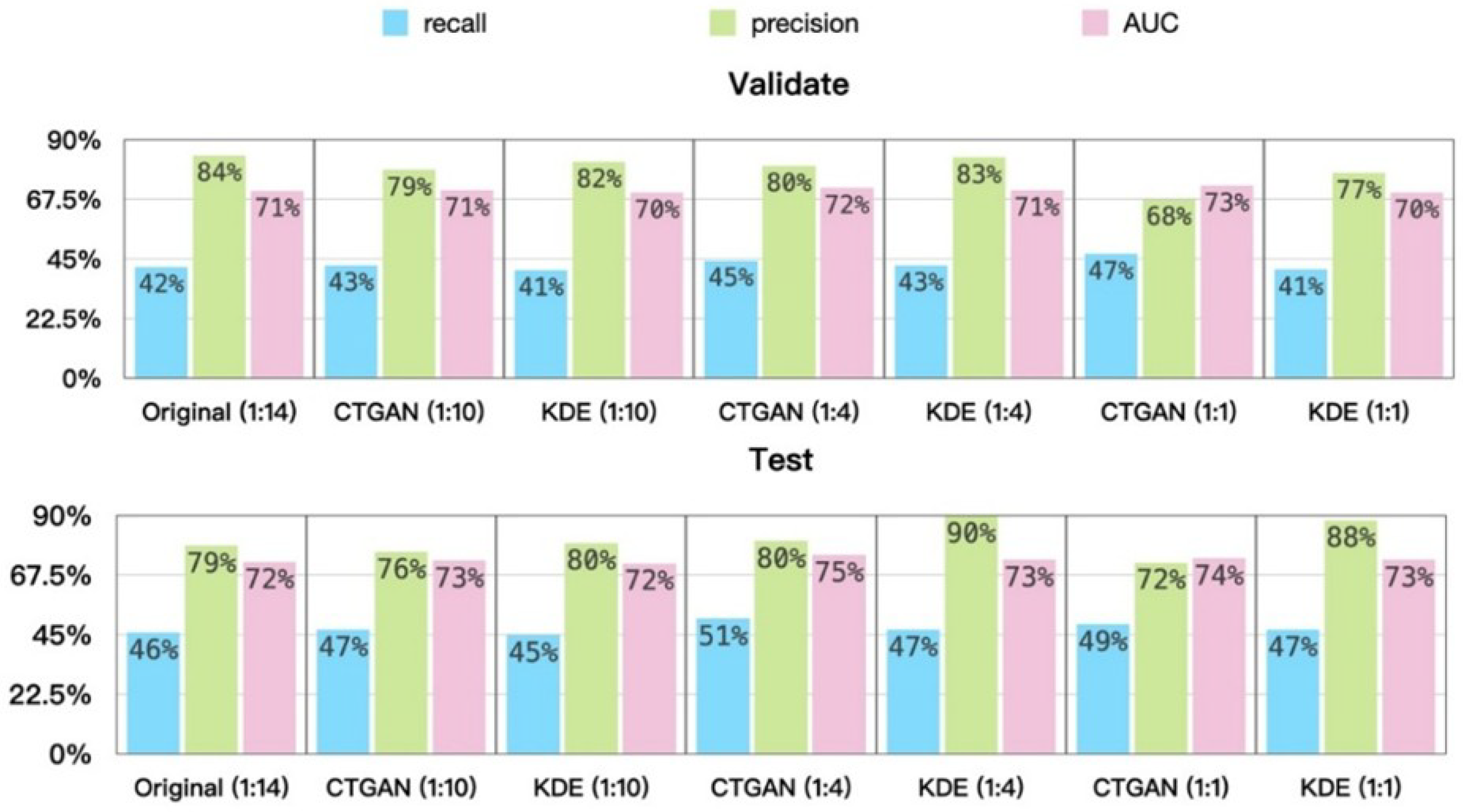

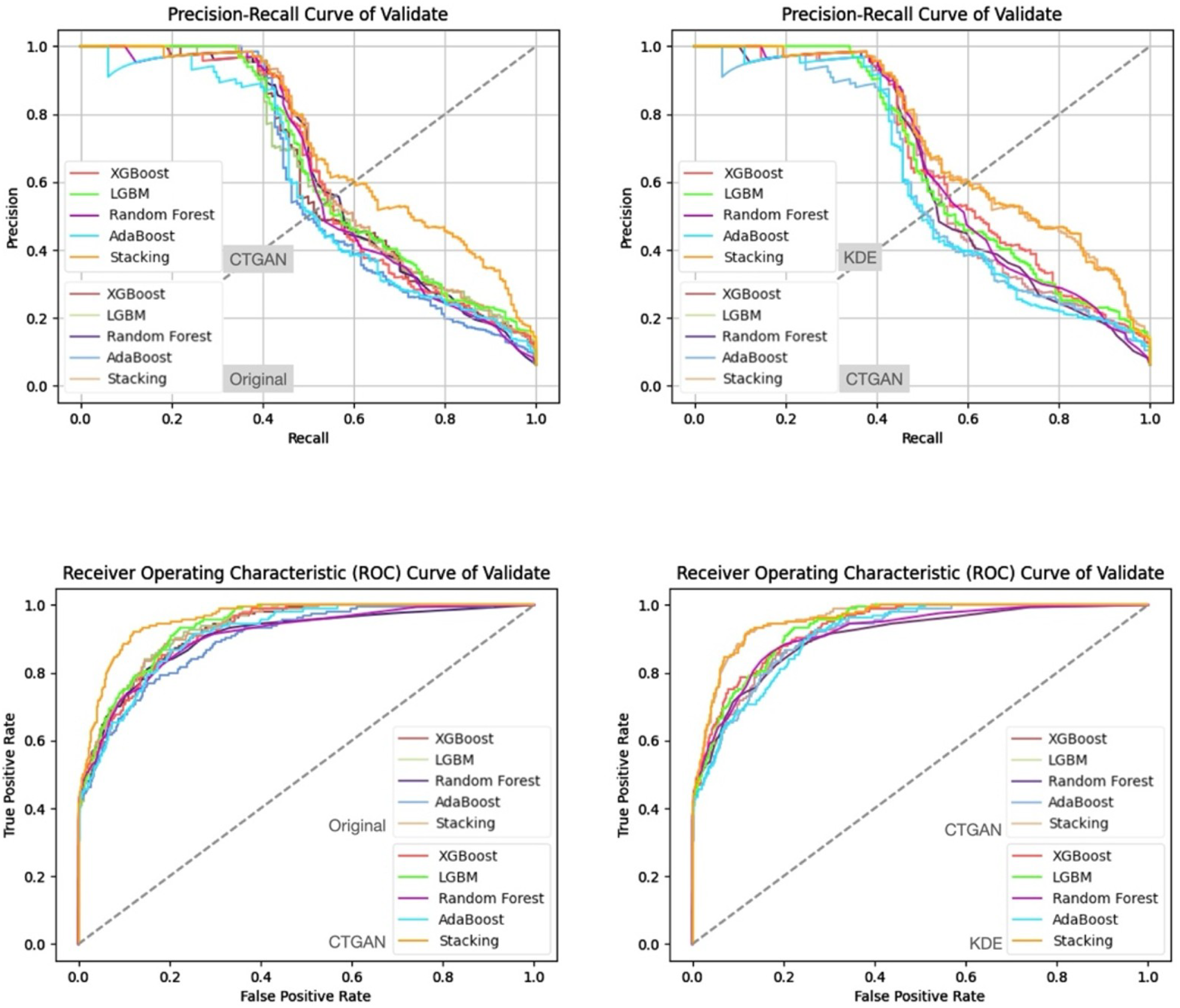

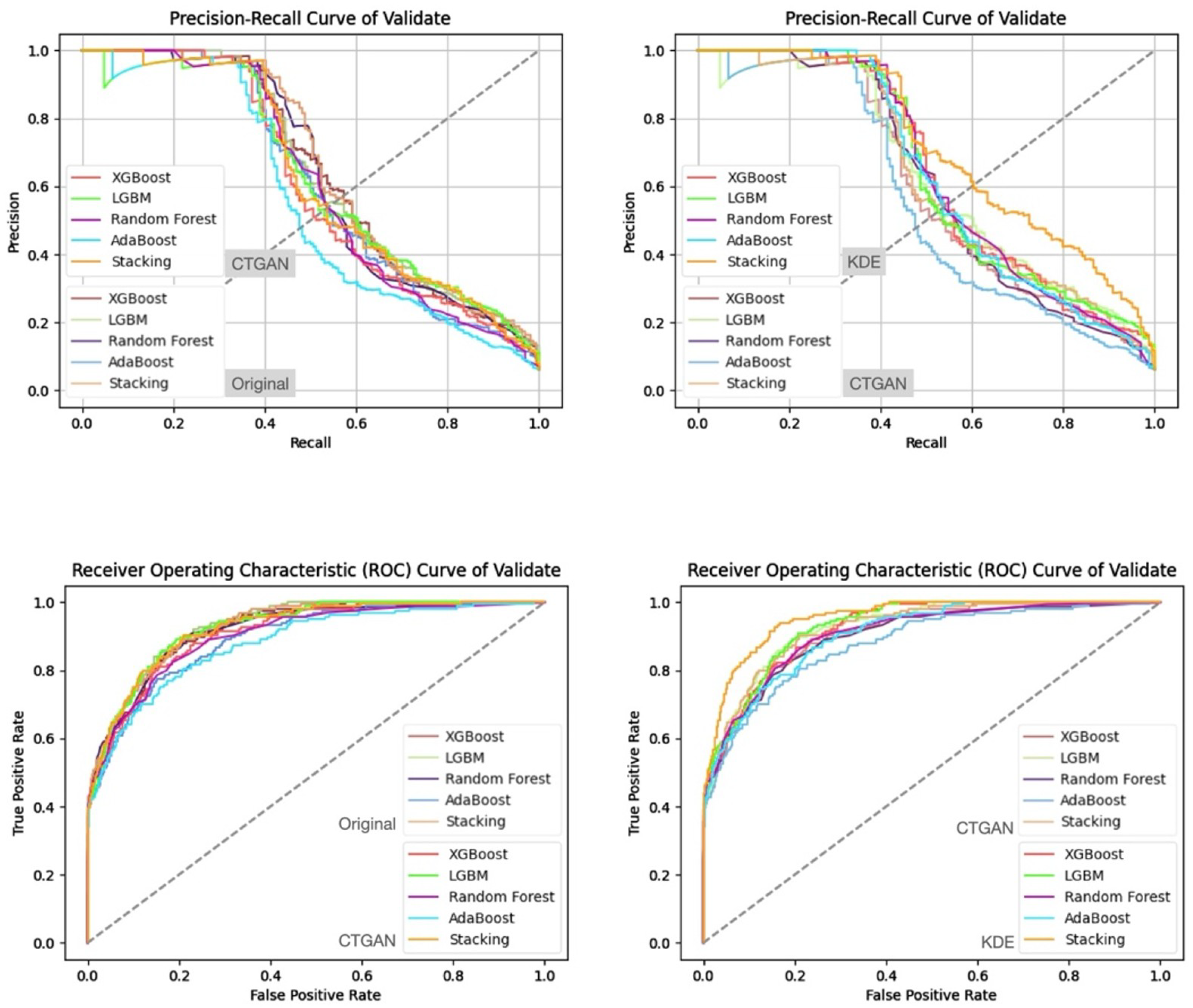

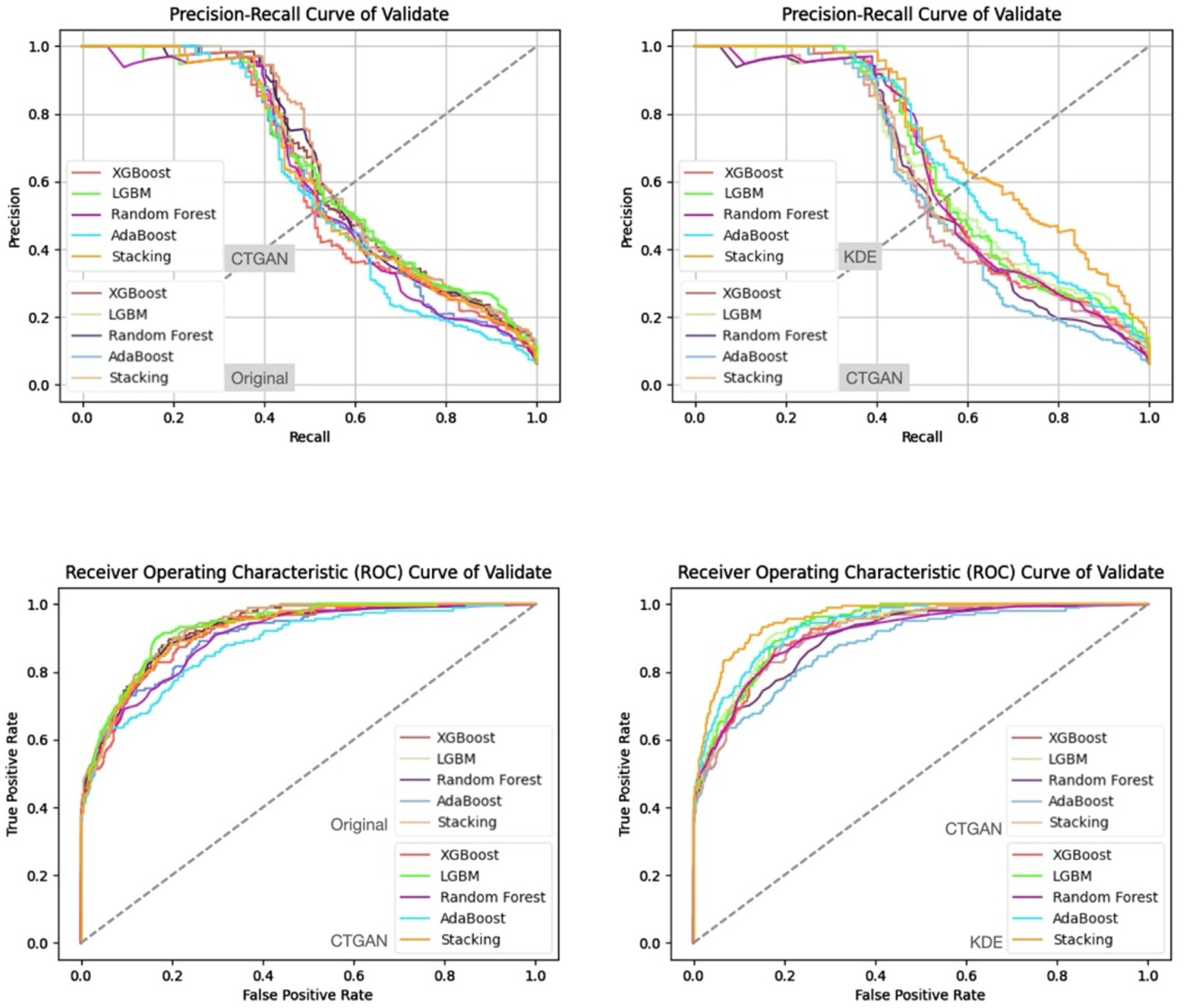

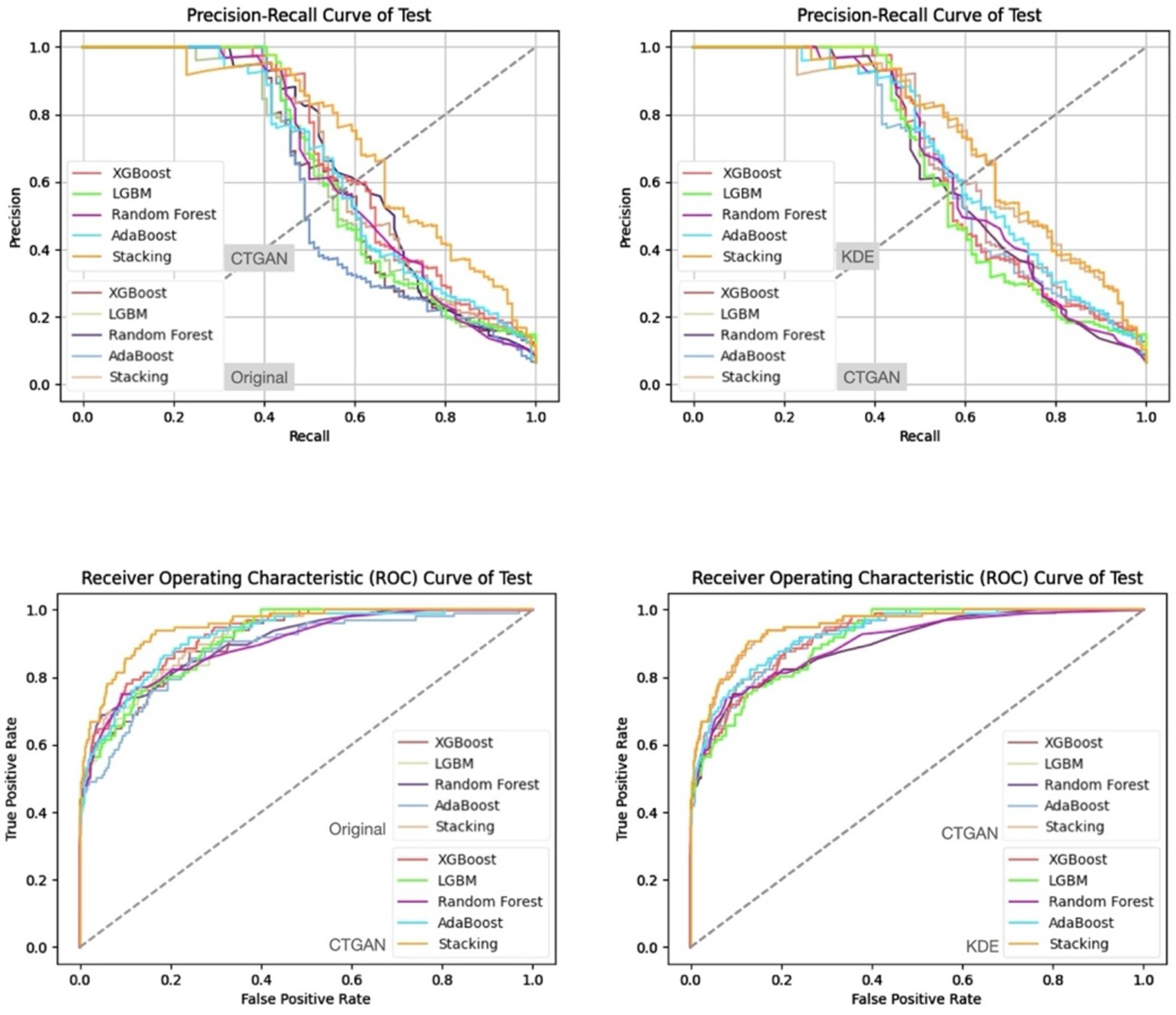

- (1)

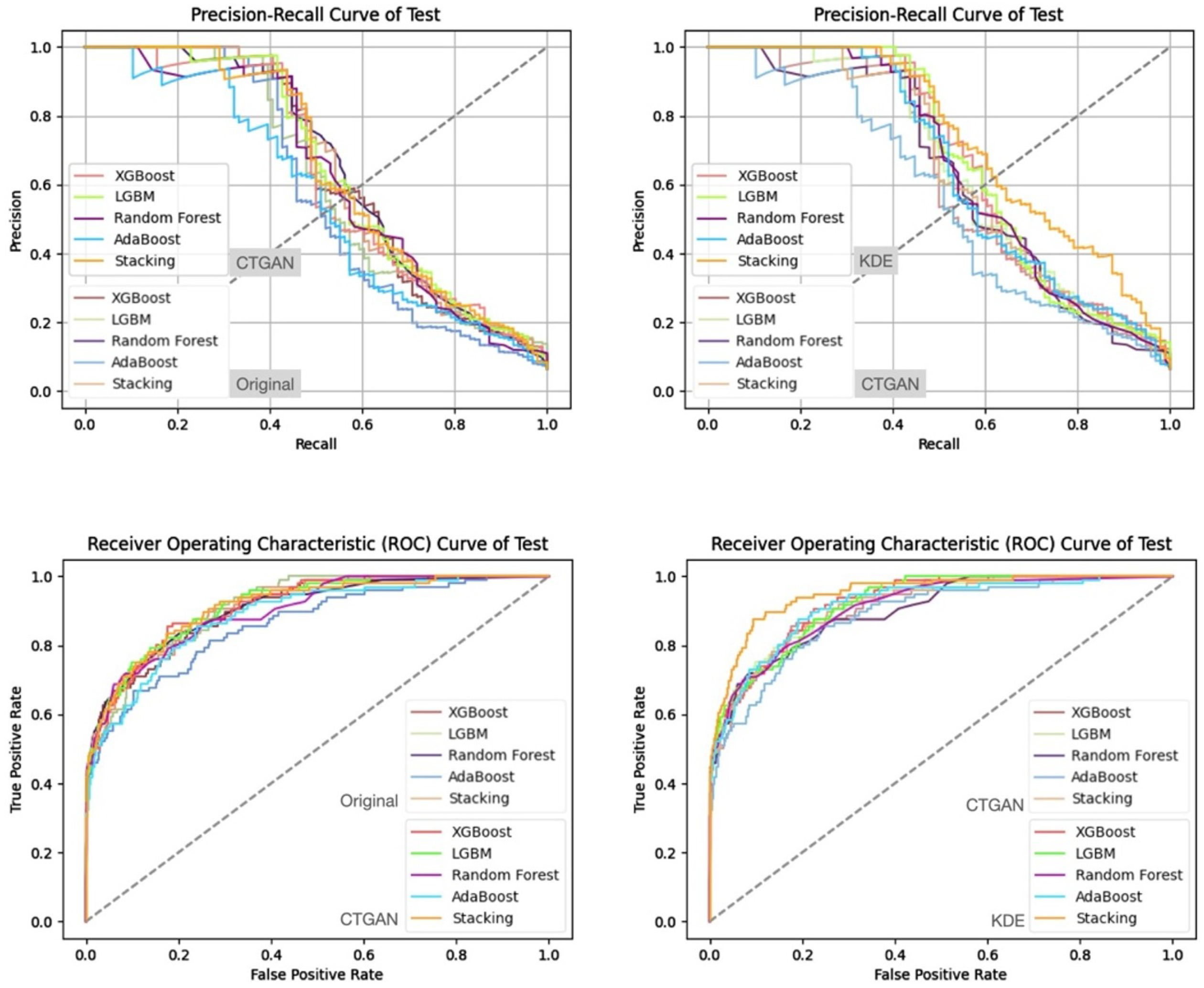

- Prediction Results on the Validation and Test Sets

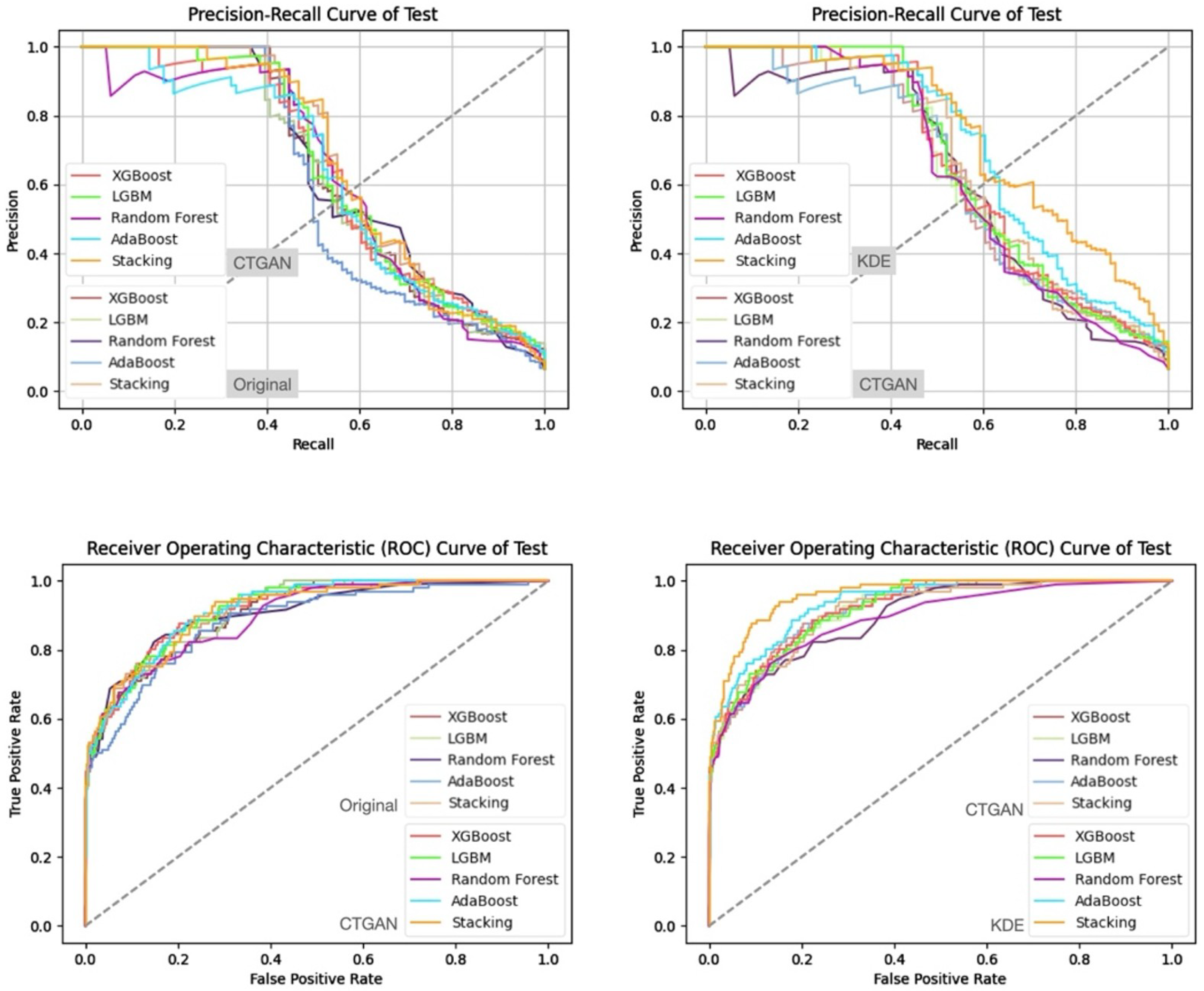

- (2)

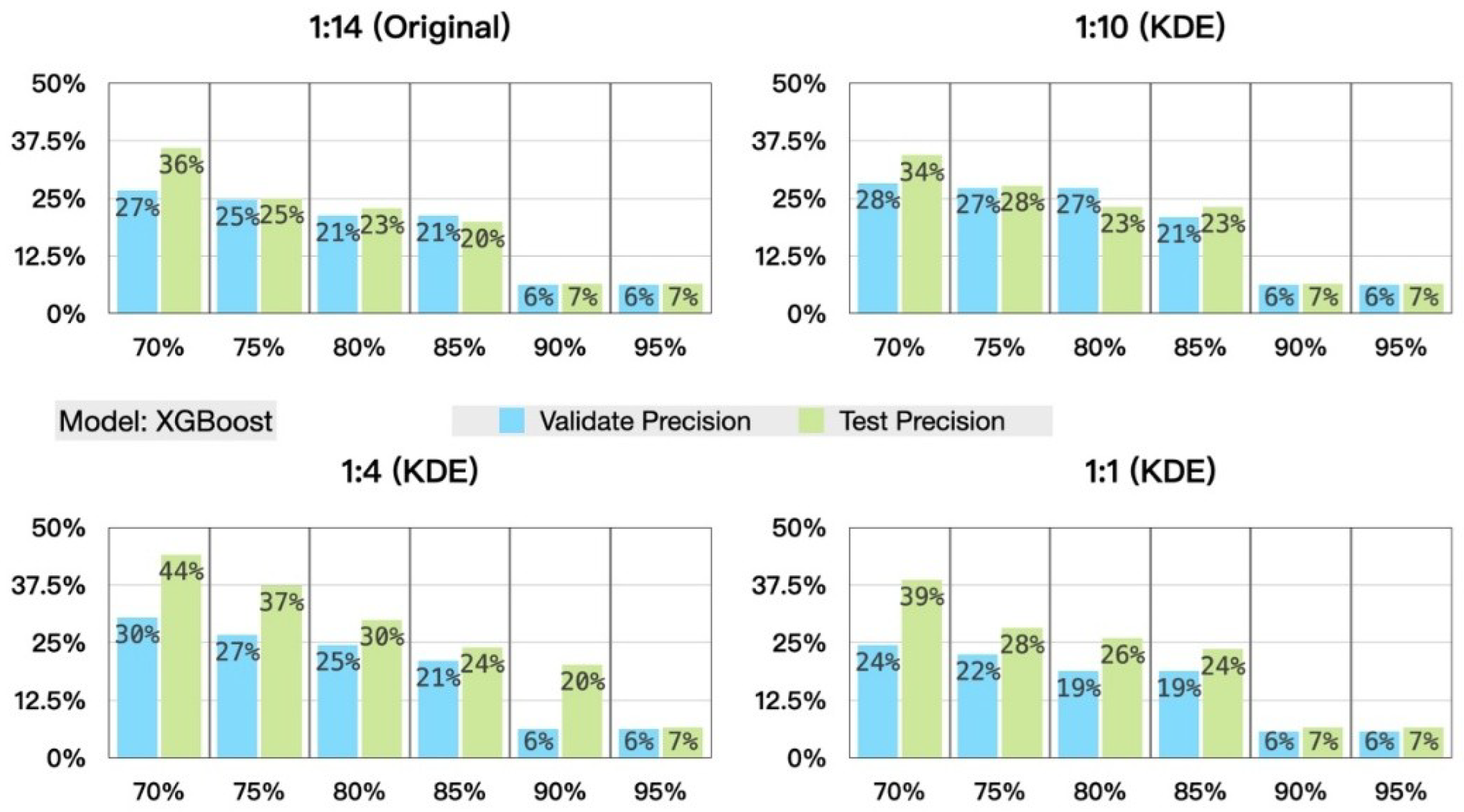

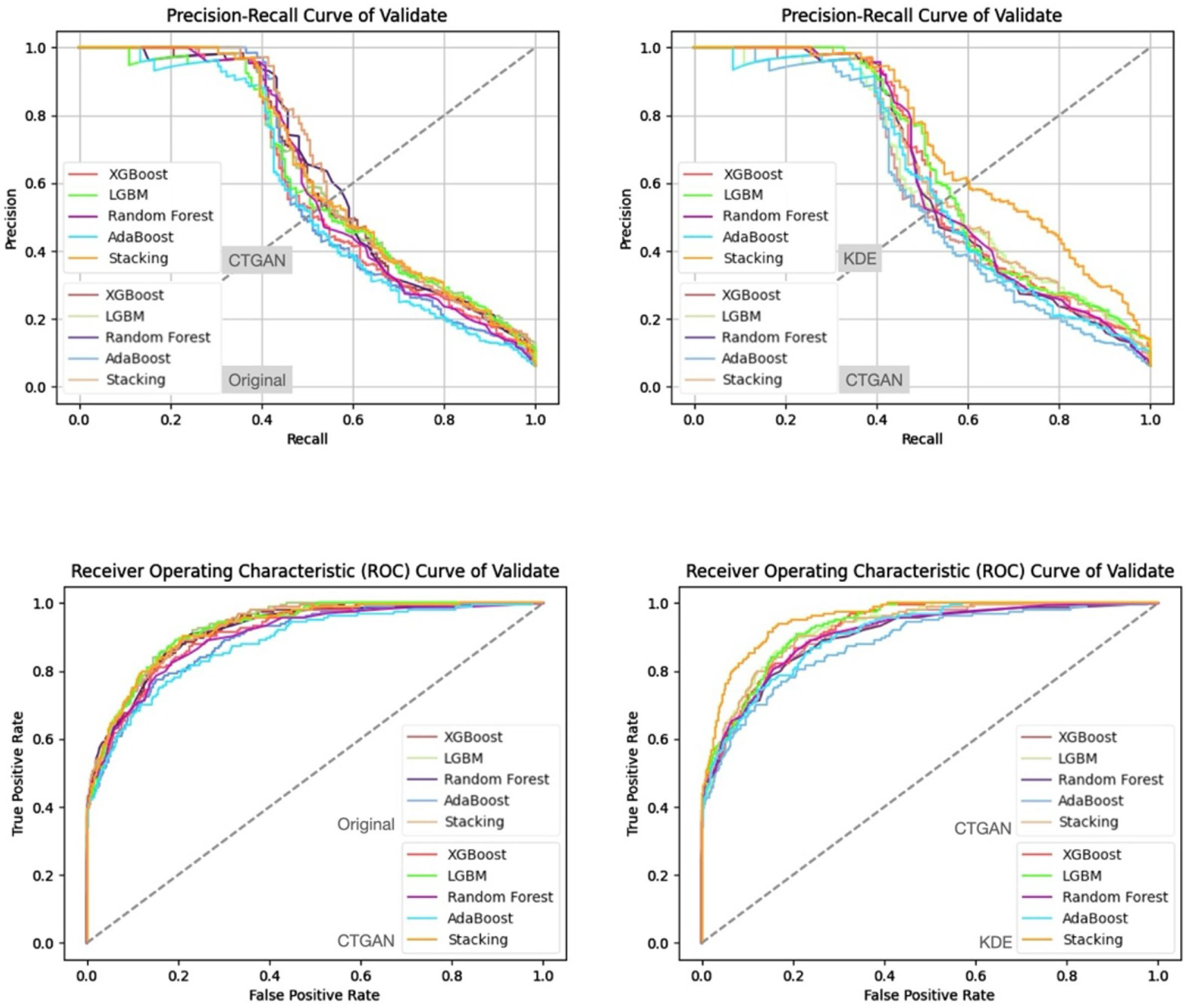

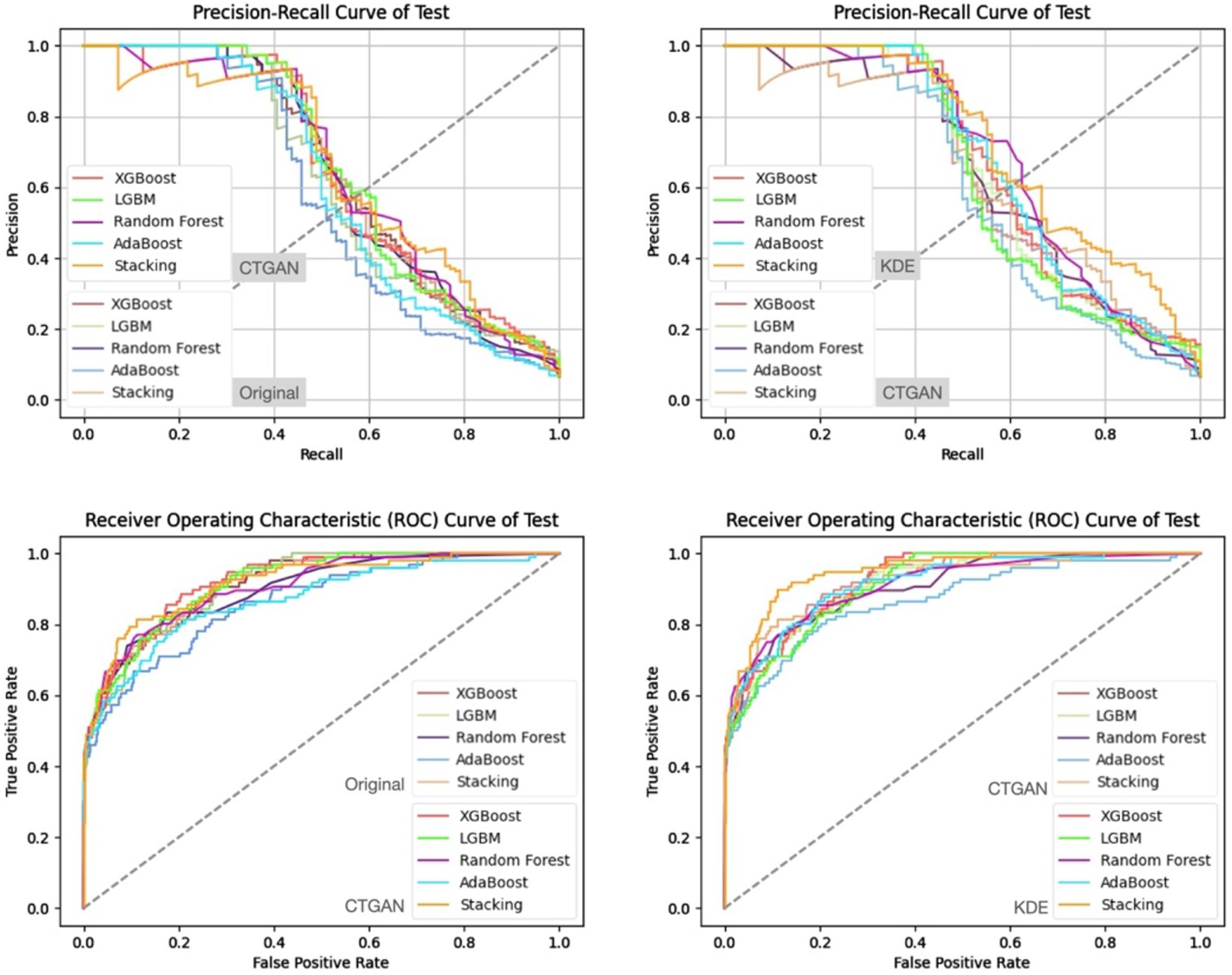

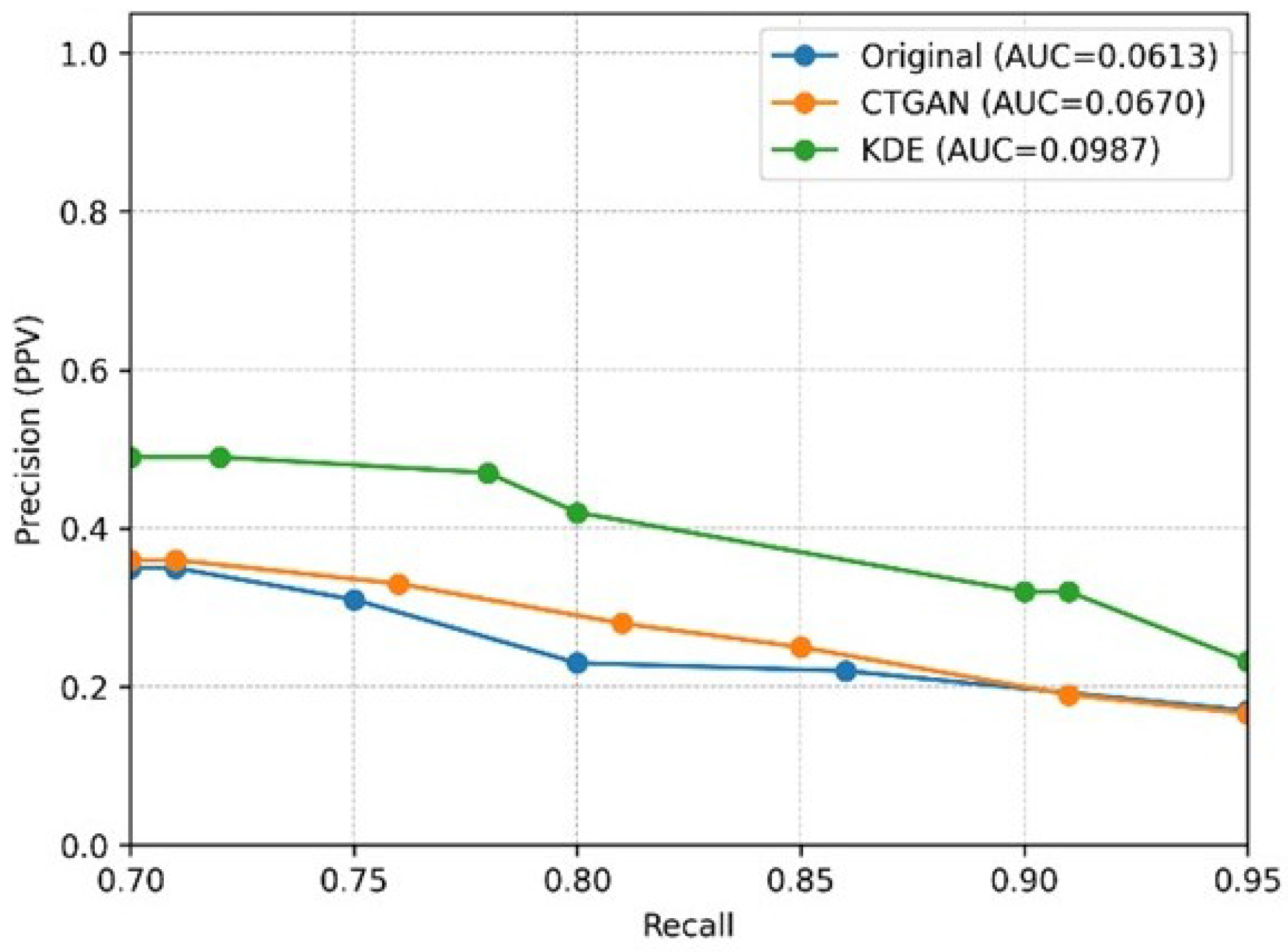

- Prediction Results of the Stratified Experiments

- (2)

- Prediction Results of the Stratified Experiments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). In Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd) (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Safiri, S.; Carson-Chahhoud, K.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Kolahi, A.-A. GBD 2019 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Collaborators. Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Its Attributable Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022, 378, e069679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global Burden of Chronic Respiratory Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-L.; Chan, M.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Hsu, J.-Y.; Hang, L.-W.; Chang, C.-J.; Perng, D.-W. COPD in Taiwan: A National Epidemiology Survey. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 2459–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.F.; Lin, K.C.; Chin, C.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Chang, H.W.; Wang, C.C.; Lin, M.C. Factors Influencing Short-Term Re-Admission and One-Year Mortality in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respirology 2007, 12, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Njoku, C.M.; Wimmer, B.C.; Alahmari, A.D.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Hurst, J.R. Risk Factors for All-Cause Hospital Readmission Following Exacerbation of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 190166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Chiara, C.; Sartori, G.; Fantin, A.; Castaldo, N.; Crisafulli, E. Reducing Hospital Readmissions in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: Current Treatments and Preventive Strategies. Medicina 2025, 61, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angra, S.; Ahuja, S. Machine Learning and Its Applications: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Big Data Analytics and Computational Intelligence (ICBDAC), Chirala, India, 23–25 March 2017; pp. 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; van Rechem, C.; Fu, T.; Wei, W. Machine Learning for Synthetic Data Generation: A Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2302.04062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhan, M.; Algarni, A.; Turki-Hadj Alouane, M. Imbalanced Data Problem in Machine Learning: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13686–13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A.; Guruswamy, G.; Smith, S.R. Synthetic Data in Health Care: A Narrative Review. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonde, B.; Traore, M.M.; Landa, P.; Côté, A.; Laberge, M. Predictive Modelling Methods of Hospital Readmission Risks: Incremental Value of Machine Learning vs. Traditional Methods. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Canay, J.; Casal-Guisande, M.; Pinheira, A.; Golpe, R.; Comesaña-Campos, A.; Fernández-García, A.; Represas-Represas, C.; Fernández-Villar, A. Predicting COPD Readmission: An Intelligent Clinical Decision Support System. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Lv, L.; Yu, X.; Cheng, X.; Liu, T.; Ji, W.; Hu, T.; Shi, Z. Development and Validation of a Nomogram for Assessing Survival in Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhu, N.T.; Kang, J.H.; Yeh, T.S.; Chang, J.H.; Tzeng, Y.T.; Chan, T.C.; Wu, C.C.; Lam, C. Predicting 14-Day Readmission in Middle-Aged and Elderly Patients with Pneumonia Using Emergency Department Data: A Multicentre Retrospective Cohort Study with a Survival Machine-Learning Approach. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, I.; Fouda, M.M.; Hosny, K.M. Machine Learning Algorithms for COPD Patients Readmission Prediction: A Data Analytics Approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15279–15287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.; Li, H.; Lipkin-Moore, Z.; Kay, S.; Rajeevan, H.; Davis, J.L.; Wilson, F.P.; Rochester, C.L.; Gomez, J.L. Deep Learning Prediction of Hospital Readmissions for Asthma and COPD. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Skoularidou, M.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Modeling Tabular Data Using Conditional GAN. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/hash/254ed7d2de3b23ab10936522dd547b78-Abstract.html (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Chen, Y.-C. A Tutorial on Kernel Density Estimation and Recent Advances. Biostat. Epidemiol. 2017, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Jung, S.; Park, S.; Hwang, E. Conditional Tabular GAN-Based Two-Stage Data Generation Scheme for Short-Term Load Forecasting. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 205327–205339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. LIII. On Lines and Planes of Closest Fit to Systems of Points in Space. Philos. Mag. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H. Stacked Generalization. Neural Netw. 1992, 5, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2699986 (accessed on 1 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.K. Random Decision Forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. Experiments with a New Boosting Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Machine Learning, Bari, Italy, 3–6 July 1996; pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hearst, M.A.; Dumais, S.T.; Osuna, E.; Platt, J.; Schölkopf, B. Support Vector Machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Appl. 1998, 13, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, Z.-H. ML-KNN: A Lazy Learning Approach to Multi-Label Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2007, 40, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.K. Introduction to Logistic Regression. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.J.; Tung, H.-Y.; Strathmann, H.; De, S.; Ramdas, A.; Smola, A.; Gretton, A. Generative Models and Model Criticism via Optimized Maximum Mean Discrepancy. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.04488. [Google Scholar]

- Khorshidi, H.A.; Aickelin, U. A synthetic over-sampling method with minority and majority classes for imbalance problems. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 5965–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | reADM Within 14 Days (N = 919) | No reADM Within 14 Days (N = 13,607) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables, No. (%) | |||

| Male sex | 751 (81.7%) | 10563 (77.6%) | 1.014 (0.841–1.222) |

| 3INCRU | 6 (0.7%) | 103 (0.8%) | 0.967 (0.379–2.465) |

| 3RELV2 | 3 (0.3%) | 40 (0.3%) | 1.096 (0.311–3.862) |

| 3SPIOL | 31 (3.4%) | 311 (2.3%) | 1.240 (0.818–1.880) |

| 3SR160 | 2 (0.2%) | 56 (0.4%) | 0.394 (0.095–1.641) |

| 3TRELE | 13 (1.4%) | 81 (0.6%) | 2.520 (1.382–4.593) |

| TABACCO | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 0.000 (0.000 to inf) |

| PN | 477 (51.9%) | 6393 (47.0%) | 1.214 (1.059–1.392) |

| Hypertension | 95 (10.3%) | 1816 (13.3%) | 0.725 (0.579–0.907) |

| MyocardialInfraction | 13 (1.4%) | 136 (1.0%) | 1.403 (0.786–2.503) |

| CongestiveHeartFailure | 77 (8.4%) | 974 (7.2%) | 1.243 (0.972–1.590) |

| PeripheralVascularDisease | 1 (0.1%) | 38 (0.3%) | 0.391 (0.053–2.862) |

| CerebrovascularDiease | 19 (2.1%) | 340 (2.5%) | 0.913 (0.570–1.462) |

| Dementia | 4 (0.4%) | 45 (0.3%) | 1.419 (0.507–3.971) |

| DiabetesMellitus | 115 (12.5%) | 1885 (13.9%) | 0.951 (0.776–1.166) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6 (0.7%) | 153 (1.1%) | 0.662 (0.290–1.511) |

| ChronicKidneyDisease | 28 (3.0%) | 534 (3.9%) | 0.798 (0.541–1.178) |

| Cancer | 89 (9.7%) | 944 (6.9%) | 1.573 (1.245–1.985) |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 (0.1%) | 11 (0.1%) | 1.150 (0.147–9.003) |

| AlcoholLiverDisease | 24 (2.6%) | 386 (2.8%) | 0.899 (0.588–1.374) |

| TB | 19 (2.1%) | 193 (1.4%) | 1.439 (0.893–2.319) |

| HBV | 15 (1.6%) | 339 (2.5%) | 0.668 (0.395–1.130) |

| HCV | 18 (2.0%) | 203 (1.5%) | 1.393 (0.852–2.278) |

| 2PNEU0 | 23 (2.5%) | 216 (1.6%) | 1.563 (1.010–2.417) |

| 2PNEUM | 9 (1.0%) | 74 (0.5%) | 1.634 (0.806–3.312) |

| 2PRE13 | 35 (3.8%) | 354 (2.6%) | 1.408 (0.982–2.018) |

| 2PRE30 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 2SYNFL | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| COPD Level | |||

| 1 | 158.0 (17.2%) | 2120.0 (15.6%) | 1.125 (0.071–1.343) |

| 2 | 57.0 (6.2%) | 564.0 (4.1%) | 1.529 (0.071–2.025) |

| 3 | 615.0 (66.9%) | 10191.0 (74.9%) | 0.678 (0.100–0.782) |

| 4 | 89.0 (9.7%) | 732.0 (5.4%) | 1.886 (0.069–2.376) |

| Continuous variables, mean (SD) | |||

| CO | 0.44 (0.14%) | 0.44 (0.14%) | 0.042 (0.010–0.181) |

| O3 | 29.31 (7.31%) | 29.14 (7.66%) | 1.011 (0.998–1.024) |

| SO2 | 4.29 (1.57%) | 4.27 (1.58%) | 0.922 (0.869–0.978) |

| NO | 3.68 (1.81%) | 3.62 (1.79%) | 1.011 (0.860–1.188) |

| NO2 | 16.90 (6.11%) | 16.52 (6.22%) | 1.081 (0.945–1.236) |

| NOx | 20.58 (7.57%) | 20.16 (7.61%) | 1.006 (0.877–1.154) |

| PM2.5 | 29.04 (12.74%) | 28.87 (13.37%) | 1.009 (0.995–1.023) |

| PM10 | 59.46 (21.67%) | 59.33 (23.31%) | 0.994 (0.986–1.002) |

| AGE | 73.01 (11.00%) | 72.84 (12.00%) | 1.011 (1.004–1.017) |

| re_ADM_TIME | 2.96 (4.01%) | 1.53 (2.74%) | 1.032 (1.014–1.050) |

| BED_DAY | 11.80 (10.09%) | 10.08 (10.40%) | 1.008 (0.999–1.018) |

| 3SPI25 | 0.15 (0.36%) | 0.11 (0.32%) | 1.278 (1.043–1.566) |

| avg_BED_DAY | 11.12 (7.92%) | 9.80 (8.29%) | 1.015 (1.001–1.029) |

| 1DL30 | 1.25 (8.44%) | 1.10 (7.83%) | 1.001 (0.993–1.009) |

| 1MEPTI | 8.75 (19.11%) | 7.26 (17.47%) | 1.001 (0.997–1.004) |

| 1PHYLL | 14.19 (23.33%) | 10.51 (20.75%) | 1.003 (1.000–1.007) |

| 1PREDN | 10.90 (26.28%) | 6.73 (18.35%) | 1.007 (1.004–1.010) |

| 1PROPH | 9.22 (23.78%) | 10.98 (25.05%) | 0.997 (0.994–1.000) |

| 3ALVES | 0.04 (0.20%) | 0.02 (0.14%) | 1.793 (1.213–2.651) |

| 3ANORO | 0.06 (0.23%) | 0.04 (0.20%) | 1.253 (0.909–1.727) |

| 3RELVA | 0.02 (0.13%) | 0.02 (0.15%) | 0.796 (0.463–1.368) |

| avg_COPD_reADM_days | 97.41 (158.24%) | 851.34 (875.23%) | 0.992 (0.992–0.993) |

| 3VENTO | 0.13 (0.34%) | 0.12 (0.32%) | 0.865 (0.700–1.068) |

| %sO2c | 94.03 (6.33%) | 94.08 (6.36%) | 0.999 (0.988–1.010) |

| ALB | 7.11 (81.66%) | 4.63 (24.32%) | 1.001 (1.000–1.002) |

| BNP | 103.97 (82.32%) | 110.86 (180.54%) | 1.000 (0.999–1.000) |

| BUN | 17.42 (14.25) | 17.41 (13.85) | 1.001 (0.995–1.006) |

| CEA | 2.38 (4.64) | 6.64 (466.76) | 0.998 (0.991–1.005) |

| CK | 119.58 (73.66) | 120.38 (266.90) | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) |

| CK-MB | 8.96 (5.09) | 8.92 (7.77) | 1.002 (0.994–1.010) |

| CRP | 9.99 (27.21) | 10.47 (28.33) | 0.998 (0.995–1.001) |

| CRTN | 1.03 (0.29) | 1.04 (0.40) | 0.888 (0.718–1.097) |

| Ca++ | 9.22 (1.26) | 9.23 (1.23) | 0.991 (0.940–1.046) |

| Cortisol | 10.47 (3.95) | 10.55 (4.87) | 0.996 (0.980–1.012) |

| D-Dimer | 0.28 (0.30) | 0.33 (2.43) | 0.949 (0.849–1.061) |

| GLU | 88.75 (23.98) | 87.91 (24.64) | 1.002 (0.999–1.005) |

| GPT | 24.33 (15.33) | 24.59 (37.90) | 1.000 (0.997–1.002) |

| HCT | 39.66 (6.28) | 39.89 (6.17) | 1.028 (0.996–1.060) |

| HDL-C | 90.27 (23.84) | 88.51 (24.15) | 1.003 (1.000–1.006) |

| HGB | 12.90 (2.05) | 13.02 (2.01) | 0.899 (0.825–0.980) |

| HbA1C | 3.03 (1.70) | 3.04 (1.79) | 1.001 (0.963–1.039) |

| IgE | 56.59 (61.60) | 58.65 (77.82) | 0.999 (0.998–1.001) |

| K | 4.02 (0.56) | 4.06 (0.57) | 0.882 (0.777–1.000) |

| LDL-C | 76.23 (14.95) | 75.95 (16.39) | 1.002 (0.998–1.006) |

| Lactate | 1.37 (0.50) | 1.38 (0.78) | 1.020 (0.910–1.142) |

| Mg | 2.01 (0.30) | 2.00 (0.30) | 1.040 (0.797–1.356) |

| Mite DF | 25.44 (14.22) | 24.76 (14.37) | 1.003 (0.999–1.008) |

| Mite/far | 24.96 (14.54) | 24.92 (14.49) | 1.000 (0.996–1.005) |

| O2SAT | 97.14 (3.49) | 97.27 (2.74) | 0.985 (0.964–1.006) |

| SCC | 1.07 (1.11) | 1.02 (0.70) | 1.069 (0.993–1.150) |

| Sugar | 90.54 (27.64) | 93.39 (62.78) | 0.998 (0.996–1.000) |

| T-BIL | 0.71 (0.70) | 0.68 (0.63) | 1.039 (0.966–1.118) |

| T-CHO | 149.15 (29.10) | 150.42 (29.38) | 0.999 (0.994–1.003) |

| T3 | 139.48 (34.18) | 140.13 (34.97) | 1.000 (0.000 to inf) |

| T4 | 139.48 (34.18) | 140.13 (34.97) | 1.000 (0.000 to inf) |

| TCO2 | 26.60 (3.84) | 26.59 (4.69) | 0.997 (0.981–1.013) |

| TG | 79.76 (41.14) | 81.22 (43.01) | 0.999 (0.998–1.001) |

| TP | 7.34 (0.56) | 7.35 (0.56) | 0.981 (0.868–1.108) |

| TSH | 2.27 (1.13) | 2.25 (2.84) | 1.002 (0.979–1.024) |

| Theophy | 0.67 (1.39) | 0.61 (1.15) | 1.032 (0.985–1.081) |

| Tropo-I | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.06 (1.24) | 0.209 (0.023–1.867) |

| WBC | 8.98 (3.46) | 8.74 (4.30) | 1.012 (0.999–1.026) |

| hsCRP | 0.51 (0.29) | 0.50 (0.29) | 1.073 (0.863–1.334) |

| pCO2 | 41.75 (7.90) | 41.51 (8.58) | 1.003 (0.994–1.011) |

| House_dust | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.10) | 1.005 (0.436–2.318) |

| Training Data and Generated Sample Ratios | 1:14 (Original) | 1:10 | 1:4 | 1:1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real positive data/percentage | 659 (100%) | 659 (67.4%) | 659 (26.9%) | 659 (6.7%) |

| Generated positive data/percentage | 0 (0.0%) | 319 (32.6%) | 1787 (73.1%) | 9126 (93.3%) |

| Total positive cases | 659 | 978 | 2446 | 9785 |

| Total negative cases | 9785 | 9785 | 9785 | 9785 |

| Total training data | 10,444 | 10,763 | 12,231 | 19,570 |

| Proportion of generated data | 0.0% | 3.0% | 14.6% | 46.6% |

| Metric | CTGAN | KDE |

|---|---|---|

| MMD | 0.00218 | 0.00117 |

| Feature | Original (E) | KDE (E) | CTGAN (E) | Original (IG) | KDE (IG) | CTGAN (IG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 1.88 | 2.01 | 2.00 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 1.81 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| 1.57 | 1.69 | 1.62 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| NO | 1.58 | 1.62 | 1.58 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 1.99 | 2.04 | 2.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| NOx | 1.92 | 2.01 | 2.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| PM2.5 | 1.95 | 1.96 | 1.96 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| PM10 | 1.97 | 2.03 | 2.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| AGE | 1.78 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| SEX | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| re_ADM_TIME | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| BED_DAY | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| avg_COPD_reADM_days | 1.83 | 1.68 | 1.68 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| avg_BED_DAY | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| 1DL30 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| 1MEPTI | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| 1PHYLL | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.40 |

| 1PREDN | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| 1PROPH | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| 3ALVES | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| 3ANORO | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| 3INCRU | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 3RELV2 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 3RELVA | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| 3SPI25 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| 3SPIOL | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| 3SR160 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 3TRELE | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 3VENTO | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| copd_level | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| %sO2c | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| ALB | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| BNP | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| BUN | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| CEA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| CK | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| CK-MB | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| CRP | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| CRTN | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| Ca++ | 1.12 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Cortisol | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| D-Dimer | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.33 |

| GLU | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| GPT | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| HCT | 1.28 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| HDL-C | 2.03 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| HGB | 1.42 | 1.47 | 1.47 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| HbA1C | 1.33 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| IgE | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| K | 0.76 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| LDL-C | 1.06 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Lactate | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Mg | 1.15 | 1.32 | 1.48 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Mite DF | 2.30 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Mite/far | 2.30 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| O2SAT | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| SCC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| Sugar | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| T-BIL | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| T-CHO | 1.46 | 1.55 | 1.55 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| T3 | 1.37 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| T4 | 1.37 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| TCO2 | 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| TG | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| TP | 1.54 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| TSH | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Theophy | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Tropo-I | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| WBC | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| hsCRP | 1.30 | 1.35 | 1.36 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| pCO2 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| House_dust | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| COPD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| TABACCO | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| Hypertension | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| PeripheralVascularDisease | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| PN | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| MyocardialInfraction | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| CongestiveHeartFailure | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| CerebrovascularDiease | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Dementia | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| DiabetesMellitus | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| ChronicKidneyDisease | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Cancer | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| AlcoholLiverDisease | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| TB | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| HBV | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| HCV | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Feature Category | Selected Features (p-Value < 0.05) |

|---|---|

| Original | |

| Basic information | ’SEX’, ’BED_DAY’, ’avg_BED_DAY’, ’avg_COPD_reADM_days’, ’re_ADM_TIME’ |

| Drug | ’1PHYLL’, ’1PREDN’, ’3ALVES’, ’3ANORO’, ’3SPI25’, ’3TRELE’ |

| Comorbidity | ’PN’, ’Cancer’ |

| KDE | |

| Basic information | ’SEX’, ’BED_DAY’, ’avg_BED_DAY’, ’avg_COPD_reADM_days’, ’re_ADM_TIME’ |

| Drug | ’1DL30’, ’1MEPTI’, ’1PHYLL’, ’1PREDN’, ’1PROPH’, ’3ALVES’, ’3ANORO’, ’3INCRU’, ’3RELVA’, ’3SPI25’, ’3SPIOL’, ’copd_level’ |

| Blood | ’HCT’, ’HGB’, ’K’, ’Mg’, ’Sugar’, ’T-CHO’ |

| Comorbidity | ’PN’, ’Hypertension’, ’CongestiveHeartFailure’, ’PeripheralVascularDisease’, ’CerebrovascularDiease’, ’Dementia’, ’DiabetesMellitus’, ’Hyperlipidemia’, ’ChronicKidneyDisease’, ’HBV’, ’Cancer’ |

| CTGAN | |

| Air quality | ’No2’ |

| Basic information | ’SEX’, ’BED_DAY’, ’avg_BED_DAY’, ’avg_COPD_reADM_days’, ’re_ADM_TIME’ |

| Drug | ’1DL30’, ’1MEPTI’, ’1PHYLL’, ’1PREDN’, ’1PROPH’, ’3ALVES’, ’3ANORO’, ’3RELV2’, ’3SPI25’, ’3TRELE’, ’3VENTO’, ’copd_level’ |

| Blood | ’CRTN’, ’GLU’, ’HCT’, ’HDL-C’, ’HGB’, ’SCC’, ’WBC’, ’hsCRP’, ’House_dust’ |

| Comorbidity | ’PN’, ’MyocardialInfraction’, ’CongestiveHeartFailure’, ’Dementia’, ’ChronicKidneyDisease’, ’Cancer’, ’HIV/AIDS’, ’HCV’ |

| Feature Set | Split | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ROC-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDE | Test | 0.94 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.948894 |

| Ridge | Test | 0.93 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.947984 |

| Validate | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| RF | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.57 |

| SC | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| Original—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.55 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| RF | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.49 | 0.60 |

| Original—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.57 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| SC | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.49 | 0.60 |

| Original—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.60 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.57 |

| RF | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| CTGAN-generated data—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.58 |

| Ada | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.50 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.58 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| SC | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.57 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.61 |

| Ada | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.32 | 0.48 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.55 |

| SC | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| LGBM | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| KDE-generated data—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| LGBM | 0.74 | 0.90 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.60 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| RF | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| SC | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.60 | 0.68 |

| KDE-generated data—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| LGBM | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.57 |

| Ada | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| SC | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.55 | 0.98 | 0.64 | 0.70 |

| KDE-generated data—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.60 |

| Ada | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| RF | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| SC | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.60 | 0.67 |

| KDE-generated data—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.55 |

| LGBM | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| RF | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| SC | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 0.98 | 0.60 | 0.67 |

| Validate | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | ||||||

| XGB | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | NaN | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| LGBM | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| Ada | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.46 |

| RF | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.20 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.53 |

| CTGAN-generated data | ||||||

| XGB | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 0.49 |

| LGBM | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| Ada | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.39 |

| RF | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.47 |

| SC | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 0.50 |

| KDE-generated data | ||||||

| XGB | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | NaN | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| LGBM | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.56 |

| Ada | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| RF | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 0.46 |

| SC | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.49 | 0.68 |

| Test | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.55 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| Original—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| RF | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.58 |

| SC | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.55 |

| Original—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.47 |

| RF | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.48 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| Original—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.50 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.47 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.59 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| CTGAN-generated data—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.57 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| RF | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.48 |

| SC | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.50 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| Ada | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.28 | 0.47 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.58 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.57 |

| LGBM | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| Ada | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.50 |

| RF | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 0.52 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.57 |

| CTGAN-generated data—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| LGBM | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.59 |

| Ada | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.34 | 0.52 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.41 | 0.58 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 0.61 |

| KDE-generated data—All features | ||||||

| XGB | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 0.56 |

| LGBM | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| Ada | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| RF | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.35 | 0.54 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 0.99 | 0.55 | 0.68 |

| KDE-generated data—Without vaccination | ||||||

| XGB | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.60 |

| LGBM | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.55 |

| Ada | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 0.43 | 0.61 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| SC | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.66 |

| KDE-generated data—Without comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.53 |

| LGBM | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.57 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.39 | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

| KDE-generated data—Without vaccination and comorbidities | ||||||

| XGB | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.58 |

| LGBM | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| Ada | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.56 |

| RF | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.56 |

| SC | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| Comparison | AUC (Stacking) | AUC (XGBoost) | DeLong p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking (AUC) vs. XGBoost | 0.9495 | 0.9178 | 0.00135 |

| Group | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | 0.20 | 0.91 | 0.33 | 0.833 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.746 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 0.838 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.27 | 0.84 | 0.41 | 0.839 |

| Validate | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall ≥ 70 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.76/0.72 | 0.96/0.95 | 0.55/0.51 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.64/0.60 | 0.70/0.67 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.75/0.71 | 0.96/0.94 | 0.53/0.42 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.63/0.52 | 0.70/0.62 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.74/0.72 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.71/0.70 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.72/0.71 | 0.73/0.72 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.80/0.78 | 0.94/0.94 | 0.53/0.52 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.64/0.62 | 0.73/0.71 |

| Recall ≥ 75 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.76/0.76 | 0.96/0.94 | 0.55/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.64/0.59 | 0.70/0.68 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.75/0.76 | 0.96/0.92 | 0.53/0.36 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.63/0.49 | 0.70/0.63 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.75/0.75 | 0.98/0.97 | 0.69/0.63 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.72/0.68 | 0.74/0.72 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.80/0.78 | 0.94/0.94 | 0.53/0.52 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.64/0.62 | 0.73/0.71 |

| Recall ≥ 80 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.80/0.82 | 0.94/0.93 | 0.47/0.44 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.59/0.57 | 0.70/0.70 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.81/0.81 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.36/0.34 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.49/0.48 | 0.64/0.64 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.87/0.81 | 0.96/0.95 | 0.59/0.52 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.71/0.64 | 0.80/0.73 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.80/0.80 | 0.94/0.93 | 0.53/0.49 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.64/0.61 | 0.73/0.71 |

| Recall ≥ 85 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.85/0.86 | 0.92/0.91 | 0.40/0.38 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.55/0.53 | 0.70/0.69 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.86/0.87 | 0.89/0.86 | 0.32/0.27 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.47/0.41 | 0.64/0.60 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.87/0.86 | 0.96/0.94 | 0.59/0.47 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.71/0.61 | 0.80/0.73 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.85/0.85 | 0.92/0.91 | 0.47/0.44 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.61/0.58 | 0.74/0.72 |

| Recall ≥ 90 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.90/0.90 | 0.87/0.84 | 0.31/0.27 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.46/0.42 | 0.65/0.62 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.91/0.90 | 0.83/0.80 | 0.24/0.21 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.38/0.35 | 0.58/0.55 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.94/0.92 | 0.48/0.43 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.63/0.58 | 0.77/0.74 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.90/0.86 | 0.44/0.36 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.59/0.51 | 0.74/0.69 |

| Recall ≥ 95 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.95/0.96 | 0.80/0.75 | 0.24/0.21 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.38/0.34 | 0.60/0.55 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.96/0.96 | 0.76/0.74 | 0.19/0.18 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.32/0.30 | 0.53/0.51 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.96/0.96 | 0.90/0.71 | 0.38/0.17 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.54/0.29 | 0.73/0.50 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.95/0.95 | 0.71/0.73 | 0.22/0.23 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.36/0.37 | 0.57/0.58 |

| Test | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall ≥ 70 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.73/0.71 | 0.97/0.97 | 0.64/0.60 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.68/0.65 | 0.71/0.68 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.71/0.71 | 0.93/0.90 | 0.37/0.30 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.49/0.42 | 0.60/0.56 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.71/0.71 | 0.97/0.97 | 0.66/0.63 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.68/0.67 | 0.70/0.69 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.70/0.70 | 0.88/0.88 | 0.40/0.38 | 0.96/0.96 | 0.51/0.49 | 0.61/0.60 |

| Recall ≥ 75 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.75/0.76 | 0.97/0.95 | 0.61/0.52 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.67/0.62 | 0.72/0.70 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.75/0.75 | 0.89/0.88 | 0.30/0.28 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.43/0.40 | 0.58/0.56 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.79/0.78 | 0.95/0.95 | 0.55/0.54 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.65/0.64 | 0.73/0.72 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.77/0.77 | 0.78/0.84 | 0.27/0.35 | 0.97/0.97 | 0.40/0.48 | 0.56/0.62 |

| Recall ≥ 80 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.81/0.80 | 0.91/0.90 | 0.38/0.37 | 0.99/0.98 | 0.51/0.50 | 0.66/0.65 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.80/0.80 | 0.83/0.85 | 0.23/0.25 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.36/0.38 | 0.54/0.55 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.81/0.86 | 0.95/0.93 | 0.54/0.47 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.64/0.60 | 0.73/0.73 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.80/0.87 | 0.74/0.80 | 0.25/0.32 | 0.97/0.98 | 0.38/0.47 | 0.56/0.65 |

| Recall ≥ 85 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.85/0.85 | 0.89/0.87 | 0.35/0.31 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.50/0.46 | 0.66/0.63 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.86/0.86 | 0.80/0.80 | 0.21/0.22 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.34/0.35 | 0.54/0.54 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.88/0.86 | 0.93/0.93 | 0.46/0.47 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.60/0.60 | 0.74/0.73 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.90/0.87 | 0.56/0.80 | 0.18/0.32 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.31/0.47 | 0.51/0.65 |

| Recall ≥ 90 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.92/0.91 | 0.80/0.83 | 0.24/0.28 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.39/0.42 | 0.59/0.62 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.74/0.74 | 0.18/0.18 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.30/0.30 | 0.50/0.50 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.93/0.91 | 0.89/0.90 | 0.37/0.40 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.53/0.55 | 0.72/0.72 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.56/0.69 | 0.18/0.25 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.31/0.39 | 0.51/0.59 |

| Recall ≥ 95 | No vaccine/No vaccine & comorbs | |||||

| ALL | 0.96/0.96 | 0.76/0.73 | 0.22/0.20 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.35/0.33 | 0.57/0.54 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.95/0.95 | 0.69/0.60 | 0.16/0.13 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.28/0.23 | 0.48/0.42 |

| Severity ≥ 3 | 0.96/0.96 | 0.82/0.78 | 0.28/0.24 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.43/0.38 | 0.64/0.60 |

| Severity ≤ 2 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.19/0.25 | 0.12/0.13 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.22/0.23 | 0.41/0.42 |

| Validate | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall ≥ 70 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.70/0.76 | 0.92/0.96 | 0.37/0.55 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.64 | 0.59/0.70 |

| n_Ada | 0.70/0.70 | 0.91/0.95 | 0.35/0.50 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.59 | 0.58/0.65 |

| n_GBDT | 0.73/0.74 | 0.90/0.95 | 0.34/0.49 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.59 | 0.59/0.67 |

| n_KNN | 0.73/0.73 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.36/0.36 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.48 | 0.60/0.60 |

| n_LGBM | 0.71/0.70 | 0.90/0.95 | 0.32/0.50 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.44/0.58 | 0.57/0.65 |

| n_RF | 0.75/0.76 | 0.90/0.94 | 0.34/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.59 | 0.60/0.68 |

| n_SVM | 0.76/0.76 | 0.90/0.94 | 0.35/0.46 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.58 | 0.61/0.67 |

| Recall ≥ 75 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.79/0.76 | 0.88/0.96 | 0.30/0.55 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.44/0.64 | 0.60/0.70 |

| n_Ada | 0.76/0.78 | 0.88/0.93 | 0.30/0.43 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.43/0.55 | 0.58/0.67 |

| n_GBDT | 0.76/0.76 | 0.90/0.94 | 0.33/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.59 | 0.60/0.68 |

| n_KNN | 0.77/0.76 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.33/0.34 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.47 | 0.61/0.61 |

| n_LGBM | 0.76/0.83 | 0.87/0.92 | 0.27/0.42 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.40/0.56 | 0.56/0.70 |

| n_RF | 0.75/0.76 | 0.90/0.94 | 0.34/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.59 | 0.60/0.68 |

| n_SVM | 0.76/0.76 | 0.90/0.94 | 0.35/0.46 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.58 | 0.61/0.67 |

| Recall ≥ 80 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.84/0.80 | 0.86/0.94 | 0.28/0.47 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.42/0.59 | 0.60/0.70 |

| n_Ada | 0.80/0.82 | 0.87/0.92 | 0.29/0.41 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.43/0.55 | 0.59/0.69 |

| n_GBDT | 0.80/0.80 | 0.85/0.93 | 0.26/0.45 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.39/0.58 | 0.57/0.69 |

| n_KNN | 0.80/0.82 | 0.87/0.87 | 0.29/0.30 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.43/0.44 | 0.59/0.61 |

| n_LGBM | 0.85/0.83 | 0.82/0.92 | 0.24/0.42 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.38/0.56 | 0.57/0.70 |

| n_RF | 0.82/0.80 | 0.87/0.93 | 0.30/0.43 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.44/0.56 | 0.61/0.69 |

| n_SVM | 0.81/0.81 | 0.87/0.93 | 0.29/0.44 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.42/0.57 | 0.59/0.69 |

| Recall ≥ 85 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.85/0.85 | 0.83/0.92 | 0.25/0.40 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.39/0.55 | 0.57/0.70 |

| n_Ada | 0.85/0.85 | 0.83/0.89 | 0.25/0.34 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.38/0.49 | 0.57/0.66 |

| n_GBDT | 0.85/0.85 | 0.82/0.91 | 0.24/0.39 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.37/0.53 | 0.56/0.69 |

| n_KNN | 0.86/0.85 | 0.81/0.84 | 0.23/0.26 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.37/0.40 | 0.56/0.59 |

| n_LGBM | 0.85/0.85 | 0.82/0.91 | 0.24/0.38 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.38/0.53 | 0.57/0.68 |

| n_RF | 0.87/0.85 | 0.84/0.91 | 0.26/0.40 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.40/0.54 | 0.59/0.69 |

| n_SVM | 0.85/0.85 | 0.84/0.91 | 0.27/0.38 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.41/0.52 | 0.59/0.68 |

| Recall ≥ 90 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.91/0.90 | 0.76/0.87 | 0.20/0.31 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.33/0.46 | 0.53/0.65 |

| n_Ada | 0.91/0.91 | 0.77/0.85 | 0.21/0.29 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.34/0.44 | 0.54/0.64 |

| n_GBDT | 0.91/0.91 | 0.74/0.87 | 0.19/0.31 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.32/0.47 | 0.52/0.66 |

| n_KNN | 0.91/0.90 | 0.76/0.76 | 0.21/0.20 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.33/0.33 | 0.54/0.53 |

| n_LGBM | 0.90/0.91 | 0.73/0.87 | 0.19/0.32 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.48 | 0.51/0.67 |

| n_RF | 0.90/0.91 | 0.75/0.88 | 0.19/0.34 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.32/0.49 | 0.52/0.68 |

| n_SVM | 0.91/0.91 | 0.76/0.88 | 0.20/0.33 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.33/0.48 | 0.54/0.67 |

| Recall ≥ 95 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.95/0.95 | 0.60/0.80 | 0.14/0.24 | 0.99/1.00 | 0.24/0.38 | 0.44/0.60 |

| n_Ada | 0.98/0.95 | 0.52/0.82 | 0.12/0.26 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.21/0.41 | 0.40/0.62 |

| n_GBDT | 0.95/0.95 | 0.60/0.83 | 0.14/0.27 | 0.99/1.00 | 0.24/0.42 | 0.44/0.63 |

| n_KNN | 0.96/0.96 | 0.66/0.65 | 0.16/0.16 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.27/0.27 | 0.47/0.47 |

| n_LGBM | 0.95/0.95 | 0.63/0.78 | 0.15/0.23 | 0.99/1.00 | 0.25/0.37 | 0.45/0.58 |

| n_RF | 0.95/0.95 | 0.62/0.83 | 0.15/0.28 | 0.99/1.00 | 0.25/0.43 | 0.45/0.64 |

| n_SVM | 0.95/0.96 | 0.62/0.82 | 0.14/0.27 | 0.99/1.00 | 0.25/0.42 | 0.45/0.63 |

| Test | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall ≥ 70 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.71/0.73 | 0.91/0.97 | 0.36/0.64 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.68 | 0.59/0.71 |

| n_Ada | 0.71/0.71 | 0.91/0.93 | 0.35/0.43 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.47/0.53 | 0.59/0.63 |

| n_GBDT | 0.71/0.71 | 0.92/0.94 | 0.39/0.47 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.50/0.56 | 0.61/0.64 |

| n_KNN | 0.71/0.71 | 0.92/0.94 | 0.39/0.47 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.50/0.56 | 0.61/0.64 |

| n_LGBM | 0.71/0.73 | 0.91/0.94 | 0.37/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.58 | 0.60/0.66 |

| n_RF | 0.71/0.72 | 0.92/0.96 | 0.38/0.53 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.49/0.61 | 0.60/0.67 |

| n_SVM | 0.71/0.72 | 0.92/0.95 | 0.37/0.52 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.49/0.60 | 0.60/0.67 |

| Recall ≥ 75 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.75/0.75 | 0.88/0.97 | 0.31/0.61 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.43/0.67 | 0.58/0.72 |

| n_Ada | 0.75/0.81 | 0.89/0.90 | 0.33/0.37 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.46/0.51 | 0.60/0.66 |

| n_GBDT | 0.75/0.79 | 0.90/0.93 | 0.33/0.42 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.55 | 0.60/0.67 |

| n_KNN | 0.75/0.76 | 0.91/0.92 | 0.36/0.41 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.48/0.53 | 0.62/0.65 |

| n_LGBM | 0.75/0.75 | 0.89/0.93 | 0.33/0.43 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.45/0.55 | 0.60/0.65 |

| n_RF | 0.78/0.75 | 0.85/0.94 | 0.27/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.40/0.59 | 0.57/0.67 |

| n_SVM | 0.75/0.75 | 0.91/0.94 | 0.36/0.48 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.49/0.58 | 0.62/0.67 |

| Recall ≥ 80 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.80/0.81 | 0.85/0.91 | 0.27/0.38 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.40/0.51 | 0.58/0.66 |

| n_Ada | 0.80/0.81 | 0.84/0.90 | 0.25/0.37 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.39/0.51 | 0.56/0.66 |

| n_GBDT | 0.80/0.82 | 0.83/0.92 | 0.25/0.41 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.38/0.55 | 0.56/0.69 |

| n_KNN | 0.80/0.81 | 0.84/0.88 | 0.26/0.32 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.39/0.46 | 0.56/0.62 |

| n_LGBM | 0.80/0.80 | 0.84/0.91 | 0.26/0.39 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.39/0.52 | 0.57/0.66 |

| n_RF | 0.81/0.81 | 0.83/0.92 | 0.25/0.41 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.39/0.54 | 0.56/0.68 |

| n_SVM | 0.80/0.81 | 0.83/0.92 | 0.24/0.42 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.37/0.55 | 0.55/0.68 |

| Recall ≥ 85 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.85/0.85 | 0.75/0.89 | 0.19/0.35 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.50 | 0.50/0.66 |

| n_Ada | 0.85/0.85 | 0.76/0.87 | 0.20/0.32 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.32/0.46 | 0.52/0.64 |

| n_GBDT | 0.85/0.86 | 0.75/0.89 | 0.19/0.35 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.50 | 0.51/0.67 |

| n_KNN | 0.91/0.85 | 0.72/0.84 | 0.19/0.27 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.42 | 0.51/0.60 |

| n_LGBM | 0.85/0.86 | 0.76/0.89 | 0.20/0.36 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.32/0.51 | 0.51/0.67 |

| n_RF | 0.86/0.86 | 0.79/0.90 | 0.22/0.38 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.36/0.53 | 0.55/0.69 |

| n_SVM | 0.86/0.86 | 0.76/0.90 | 0.20/0.37 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.33/0.52 | 0.52/0.68 |

| Recall ≥ 90 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.91/0.92 | 0.71/0.80 | 0.18/0.24 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.30/0.39 | 0.50/0.59 |

| n_Ada | 0.92/0.91 | 0.64/0.85 | 0.15/0.29 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.26/0.44 | 0.46/0.64 |

| n_GBDT | 0.91/0.91 | 0.70/0.87 | 0.17/0.32 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.29/0.47 | 0.49/0.66 |

| n_KNN | 0.91/0.92 | 0.72/0.79 | 0.19/0.23 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.37 | 0.51/0.58 |

| n_LGBM | 0.91/0.91 | 0.71/0.85 | 0.18/0.30 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.30/0.45 | 0.50/0.65 |

| n_RF | 0.91/0.92 | 0.72/0.86 | 0.19/0.31 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.47 | 0.51/0.66 |

| n_SVM | 0.91/0.91 | 0.72/0.86 | 0.18/0.31 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.31/0.46 | 0.51/0.65 |

| Recall ≥ 95 | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| Stacking | 0.97/0.96 | 0.61/0.76 | 0.15/0.22 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.26/0.35 | 0.46/0.57 |

| n_Ada | 0.97/0.96 | 0.50/0.75 | 0.12/0.21 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.21/0.34 | 0.40/0.56 |

| n_GBDT | 0.96/0.96 | 0.62/0.72 | 0.15/0.19 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.26/0.32 | 0.46/0.53 |

| n_KNN | 0.98/0.96 | 0.63/0.72 | 0.16/0.19 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.27/0.32 | 0.48/0.53 |

| n_LGBM | 0.96/0.97 | 0.64/0.69 | 0.16/0.18 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.27/0.30 | 0.47/0.51 |

| n_RF | 0.96/0.96 | 0.62/0.80 | 0.15/0.25 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.26/0.40 | 0.46/0.61 |

| n_SVM | 0.96/0.97 | 0.63/0.77 | 0.15/0.23 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.26/0.37 | 0.47/0.58 |

| Valid | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| n_Ada | 0.71/0.71 | 0.87/0.88 | 0.28/0.29 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.40/0.41 | 0.54/0.55 |

| n_GBDT | 0.73/0.72 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.34/0.34 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.47/0.47 | 0.59/0.59 |

| n_KNN | 0.76/0.70 | 0.78/0.92 | 0.19/0.38 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.30/0.49 | 0.47/0.60 |

| n_LGBM | 0.71/0.71 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.33/0.33 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.45/0.45 | 0.58/0.57 |

| n_RF | 0.71/0.71 | 0.88/0.90 | 0.27/0.33 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.40/0.45 | 0.54/0.58 |

| SVM | 1.00/0.98 | 0.00/0.39 | 0.06/0.10 | -/1.00 | 0.12/0.18 | 0.25/0.35 |

| Test | Recall | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F1 Score | F2 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model | CTGAN/KDE | |||||

| n_Ada | 0.73/0.72 | 0.83/0.92 | 0.23/0.39 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.35/0.51 | 0.51/0.62 |

| n_GBDT | 0.72/0.72 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.34/0.34 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.46/0.46 | 0.59/0.59 |

| n_KNN | 0.72/0.88 | 0.77/0.85 | 0.18/0.28 | 0.98/0.99 | 0.29/0.43 | 0.45/0.62 |

| n_LGBM | 0.73/0.72 | 0.91/0.90 | 0.35/0.34 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.47/0.46 | 0.60/0.59 |

| n_RF | 0.72/0.71 | 0.88/0.92 | 0.30/0.39 | 0.98/0.98 | 0.42/0.50 | 0.56/0.61 |

| n_SVM | 1.00/0.98 | 0.00/0.38 | 0.07/0.10 | -/1.00 | 0.12/0.18 | 0.26/0.35 |

| Method | ROC-AUC | Precision | Recall | F1 | Specificity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOMM | 0.9346 | 0.35 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 0.899 | 0.89 |

| KDE | 0.9491 | 0.42 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.923 | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ko, Y.-H.; Hung, C.-S.; Lin, C.-H.R.; Wu, D.-W.; Huang, C.-H.; Lin, C.-T.; Tsai, J.-H. Tackling Imbalanced Data in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis: An Ensemble Learning Approach with Synthetic Data Generation. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010105

Ko Y-H, Hung C-S, Lin C-HR, Wu D-W, Huang C-H, Lin C-T, Tsai J-H. Tackling Imbalanced Data in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis: An Ensemble Learning Approach with Synthetic Data Generation. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleKo, Yi-Hsin, Chuan-Sheng Hung, Chun-Hung Richard Lin, Da-Wei Wu, Chung-Hsuan Huang, Chang-Ting Lin, and Jui-Hsiu Tsai. 2026. "Tackling Imbalanced Data in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis: An Ensemble Learning Approach with Synthetic Data Generation" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010105

APA StyleKo, Y.-H., Hung, C.-S., Lin, C.-H. R., Wu, D.-W., Huang, C.-H., Lin, C.-T., & Tsai, J.-H. (2026). Tackling Imbalanced Data in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis: An Ensemble Learning Approach with Synthetic Data Generation. Bioengineering, 13(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010105