Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients: Facemask vs. Functional Appliance: Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Diagnosis of Class III dento-skeletal malocclusion.

- Pre- and post-treatment radiographs X rays.

- Age between 8 and 10 years at the start of treatment.

- Adequate cooperation during the treatment.

- Lack of complete and correct radiographic documentation.

- Insufficient compliance with treatment protocols.

- Systemic or growth diseases that could influence the results.

- Previous orthodontic treatment.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Ridder, L.; Aleksieva, A.; Willems, G.; Declerck, D.; Cadenas de Llano-Pérula, M. Prevalence of Orthodontic Malocclusions in Healthy Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Wu, J.; Zhao, W.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Burrow, M.F.; Tsoi, J.K.H. Artificial intelligence in dentistry—A review. Front. Dent. Med. 2023, 4, 1085251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, S.; Li, S.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, J. Comparison of cost-effectiveness and benefits of surgery-first versus orthodontics-first orthognathic correction of skeletal class III malocclusion. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandall, N.; Aleid, W.; Cousley, R.; Curran, E.; Caldwell, S.; DiBiase, A.; Dyer, F.; Littlewood, S.; Nute, S.; Campbell, S.J.; et al. The effectiveness of bone anchored maxillary protraction (BAMP) in the management of class III skeletal malocclusion in children aged 11–14 years compared with an untreated control group: A multicentre two-arm parallel randomised controlled trial. J. Orthod. 2024, 51, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, N.E.; Dalci, O.; Dalci, K.; Altug, A.T.; Darendeliler, M.A. A retrospective comparison of two protocols for correction of skeletal Class III malocclusion in prepubertal children: Hybrid hyrax expander with mandibular miniplates and rapid maxillary expansion with face mask. Prog. Orthod. 2023, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBiase, A.T.; Seehra, J.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Cobourne, M.T. Do we get better outcomes from early treatment of Class III discrepancies? Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maspero, C.; Galbiati, G.; Giannini, L.; Farronato, G. Sagittal and vertical effects of transverse sagittal maxillary expander (TSME) in three different malocclusion groups. Prog. Orthod. 2015, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellion, M.; Lisson, J.A. Dentofacial and skeletal effects of two orthodontic maxillary protraction protocols: Bone anchors versus facemask. Head. Face Med. 2024, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Galbiati, G.; Giannini, L.; Guenza, G.; Esposito, L.; Farronato, G. Titanium TSME appliance for patients allergic to nickel. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2018, 19, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, L.; Lin, H.; Huang, H. The effect of combined maxillary pad movable appliance and FR-III functional appliance in the treatment of skeletal Class III malocclusion of deciduous teeth. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcílio Santos, E.; Kalil Bussadori, S.; Ratto Tempestini Horliana, A.C.; Moraes Moriyama, C.; Jansiski Motta, L.; Pecoraro, C.; Cabrera Martimbianco, A.L. Functional orthopedic treatment for anterior open bite in children. A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2023, 84, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, D.; Watkinson, S.; Harrison, J.E.; Turner, S.; Worthington, H.V. Orthodontic treatment for prominent lower front teeth (Class III malocclusion) in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 4, CD003451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, P.; Moon, W. Evolution of Class III treatment in orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2015, 148, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farronato, G.; Rosso, G.; Giannini, L.; Galbiati, G.; Maspero, C. Correlation between skeletal Class II and temporomandibular joint disorders: A literature review. Minerva Stomatol. 2016, 65, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maspero, C.; Galbiati, G.; Perillo, L.; Favero, L.; Giannini, L. Orthopaedic treatment efficiency in skeletal Class III malocclusions in young patients: RME-face mask versus TSME. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caruso, S.; Lisciotto, E.; Caruso, S.; Marino, A.; Fiasca, F.; Buttarazzi, M.; Sarzi Amadè, D.; Evangelisti, M.; Mattei, A.; Gatto, R. Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expander and Delaire Mask Treatment on Airway Sagittal Dimensions in Pediatric Patients Affected by Class III Malocclusion and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, C.; Bai, D.; Su, N.; Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Han, X. Treatment effectiveness of Frankel function regulator on the Class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatienė, K.; Trumpytė, K. Relationship between unilateral posterior crossbite and mandibular asymmetry during late adolescence. Stomatologija 2018, 20, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, H.; Sözen, T.; Öğretmenoğlu, O.; Ciğer, S. Evaluation of the Effects of Orthopedic Treatment on the Dentofacial Structure and Upper Airway of Subjects with Skeletal Class III Malocclusion. Turk. J. Orthod. 2024, 37, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroccia, F.; Juloski, J.; Juloski, J.; Marti, P.; Lampus, F.; Vichi, A.; Giuntini, V.; Rutili, V.; Nieri, M.; Goracci, C.; et al. 3D printed customized facemask for early treatment of Class III malocclusion: A two-center case series feasibility study. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2025, 74, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, K.; Vijaykumar, N.M.; Sainath, M.C. Management of skeletal Class III malocclusion with face mask therapy and comprehensive orthodontic treatment. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahajowski, M.; Lis, J.; Sarul, M. Orthodontic Compliance Assessment: A Systematic Review. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafaie, K.; Rizk, M.Z.; Basyouni, M.E.; Daniel, B.; Mohammed, H. Tele-orthodontics and sensor-based technologies: A systematic review of interventions that monitor and improve compliance of orthodontic patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N. Compliance with removable orthodontic appliances. Evid. Based Dent. 2017, 18, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foersch, M.; Jacobs, C.; Wriedt, S.; Hechtner, M.; Wehrbein, H. Effectiveness of maxillary protraction using facemask with or without maxillary expansion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, P.; Yiu, C.; Hu, A.; Hägg, U.; Wei, S.H.; Gunel, E. Cephalometric and occlusal changes following maxillary expansion and protraction. Eur. J. Orthod. 1998, 20, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccetti, T.; McGill, J.S.; Franchi, L.; McNamara, J.J.A.; Tollaro, I. Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1998, 113, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, L.; Baccetti, T.; Tollaro, I. Predictive variables for the outcome of early functional treatment of Class III malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1997, 112, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snigdha, P.; Sumita, M. Treatment of Class III with Facemask Therapy. Case Rep. Dent. 2016, 2016, 6390637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıçoğlu, H.; Öğütlü, N.Y.; Uludağ, C.A. Evaluation of Skeletal and Dental Effects of Modified Jasper Jumper Appliance and Delaire Face Mask with Pancherz Analysis. Turk. J. Orthod. 2017, 30, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarangal, H.; Namdev, R.; Garg, S.; Saini, N.; Singhal, P. Treatment Modalities for Early Management of Class III Skeletal Malocclusion: A Case Series. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2020, 11, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farronato, G.; Giannini, L.; Galbiati, G.; Stabilini, S.A.; Maspero, C. Orthodontic-surgical treatment: Neuromuscular evaluation in open and deep skeletal bite patients. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Galbiati, G.; Giannini, L.; Guenza, G.; Farronato, M. Class II division 1 malocclusions: Comparisons between one- and two-step treatment. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2018, 19, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.K.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Son, D.W.; Choi, T.H. Comparison of treatment effects between two types of facemasks in early Class III patients. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 9, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro, V.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Malcangi, G.; Limongelli, L.; Marinelli, G.; Coloccia, G.; Laudadio, C.; Patano, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Bordea, I.R.; et al. Compliance of children with removable functional appliance with microchip integrated during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2021, 35 (Suppl. S1), 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lena, Y.; Bozkurt, A.P.; Yetkiner, E. Patients’ and Parents’ Perception of Functional Appliances: A Survey Study. Turk. J. Orthod. 2017, 30, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.F.; Lu, T.C.; Chang, C.S.; Chen, Y.A.; Chen, Y.F.; Chen, Y.R. Surgical Occlusion Setup and Skeletal Stability of Correcting Cleft-Associated Class III Deformity Using Surgery-First Bimaxillary Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 1160e–1170e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maspero, C.; Galbiati, G.; Del Rosso, E.; Farronato, M.; Giannini, L. RME: Effects on the nasal septum. A CBCT evaluation. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arqub, S.A.; Al-Zubi, K.; Iverson, M.G.; Ioannidou, E.; Uribe, F. The biological sex lens on early orthopaedic treatment duration and outcomes in Class III orthodontic patients: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakali, L.; Christopoulou, I.; Tsolakis, I.A.; Sabaziotis, D.; Alexiou, A.; Sanoudos, M.; Tsolakis, A.I. Mid-term follow up effectiveness of facemask treatment in class III malocclusion: A systematic review. Int. Orthod. 2021, 19, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

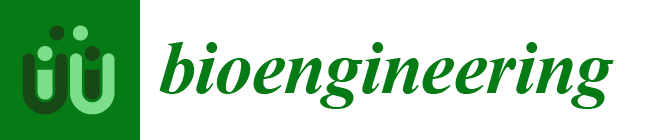

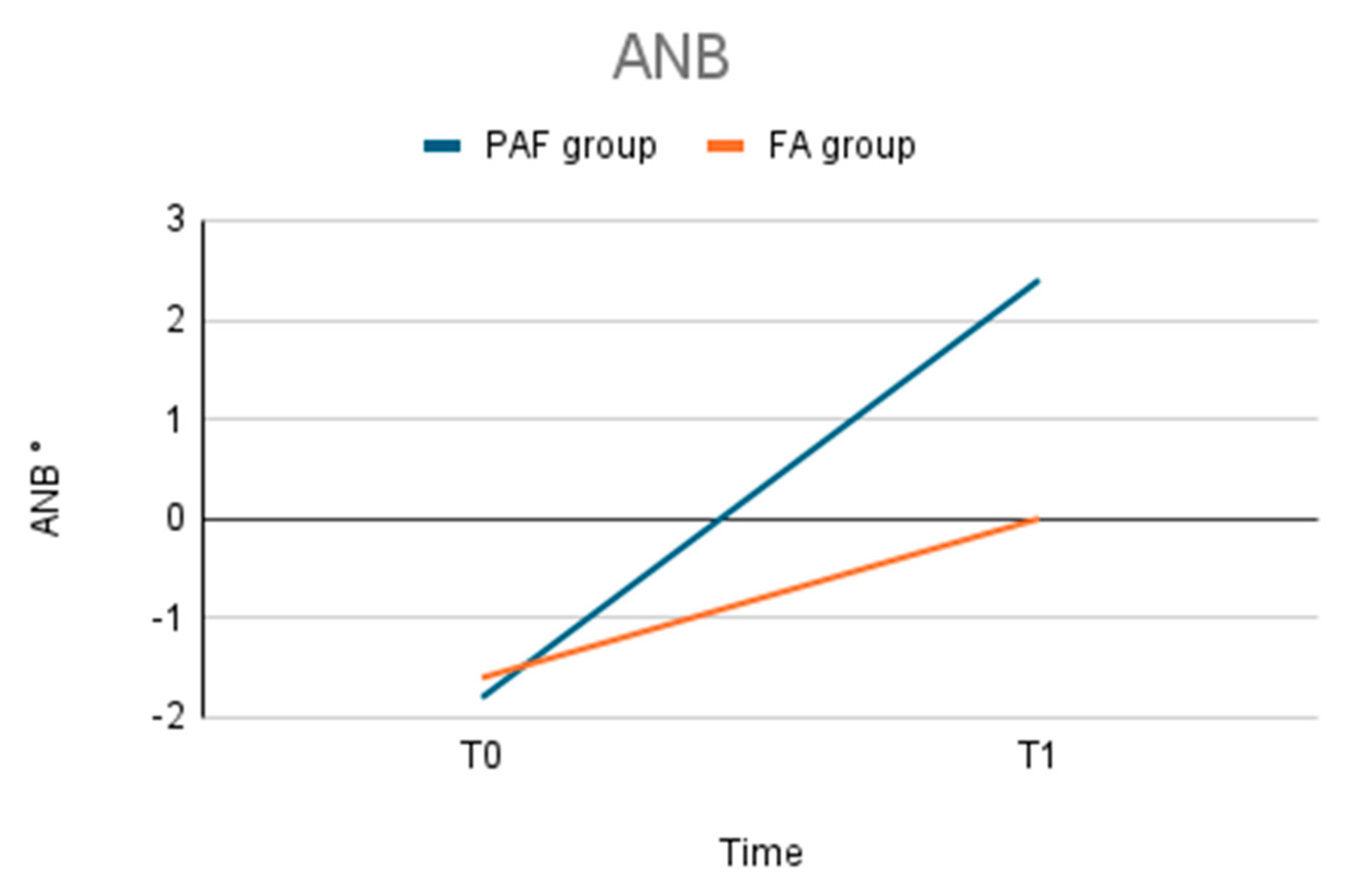

| PAF | PAF | FA | FA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |

| ANB (°) | −1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | −1.6 ± 0.4 | 0 ± 0.3 |

| SNA (°) | 77.5 ± 0.2 | 82 ± 0.3 | 77.7 ± 0.4 | 81.4 ± 0.3 |

| SNB (°) | 79.3 ± 0.4 | 79.6 ± 0.3 | 79.3 ± 0.1 | 81.3 ± 0.2 |

| WITS (mm) | 0 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | −0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| vertical facial height difference (mm) | −1.3 ± 0.7 | +0.5 ± 0.2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannini, L.; Galbiati, G.; Maspero, C.; Dipalma, G.; Biagi, R. Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients: Facemask vs. Functional Appliance: Experimental Study. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12101027

Giannini L, Galbiati G, Maspero C, Dipalma G, Biagi R. Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients: Facemask vs. Functional Appliance: Experimental Study. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(10):1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12101027

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannini, Lucia, Guido Galbiati, Cinzia Maspero, Gianna Dipalma, and Roberto Biagi. 2025. "Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients: Facemask vs. Functional Appliance: Experimental Study" Bioengineering 12, no. 10: 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12101027

APA StyleGiannini, L., Galbiati, G., Maspero, C., Dipalma, G., & Biagi, R. (2025). Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients: Facemask vs. Functional Appliance: Experimental Study. Bioengineering, 12(10), 1027. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12101027