Common Pool Resource Management: Assessing Water Resources Planning for Hydrologically Connected Surface and Groundwater Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Building-Blocks for a Common Pool of Water Resources

Water Resources Management and Policy in Nebraska

- Clearly defined boundaries: This principle states that managers should clearly define the boundary of the CPR and who has rights to withdraw resources. In the absence of clearly defined boundaries there is little incentive to coordinate, because of the risk that “free riders” will benefit from, and eventually destroy, the resource.

- Appropriation rules relevant to local conditions: Each CPR is unique in its conditions for water use. Incentives to cooperate depend on usage rules that are reasonable and reflect the situation. A “one-size-fits all” approach to managing water supply and use discourages cooperation at the local level.

- Participation by users: The individuals who directly interact with the CPR and with one another on a local level are in the best position to modify operations over time, and therefore they are motivated to participate in decision-making.

- Monitoring by users: Despite shared norms valuing compliance with cooperative arrangements, most cases of long-enduring common pool resources involve active investments in monitoring by the resource users themselves. Local users are bound by these arrangements to effectively monitor the common pool resource.

- Graduated sanctions: Punishment for non-compliance by actors in robust self-governing settings occurs in graduated steps, because local monitors are familiar with the individuals and circumstances of the infraction.

- Accessible conflict resolution: Conflicts are often resolved informally by local leaders in robust CPR settings.

- Recognition of local rules: External government officials recognize the authority and legitimacy of rules that are developed by local actors.

- Nested enterprises: Established rules for management of CPRs at the local level are nested within rules at higher-level governmental jurisdictions, creating a complete system of governance.

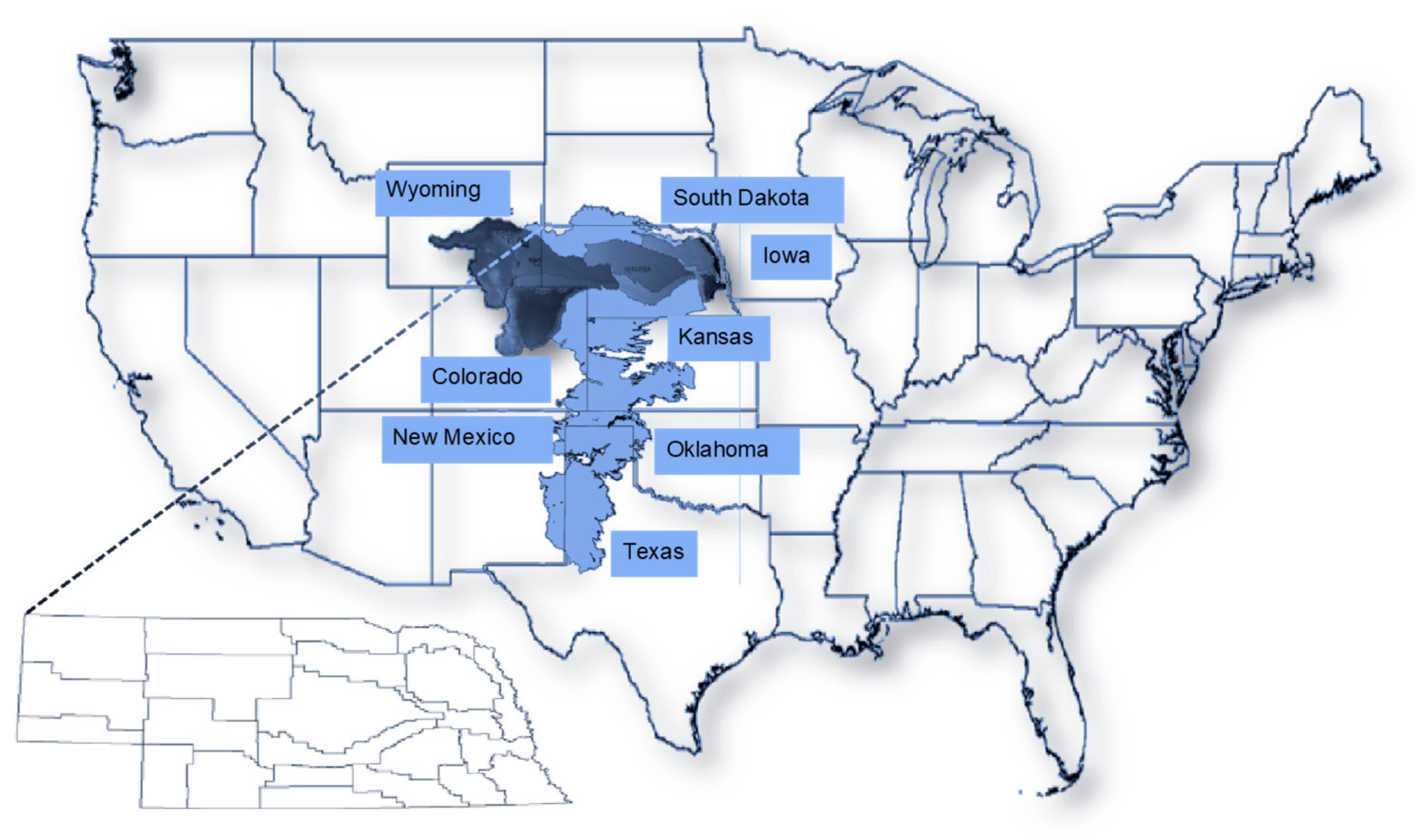

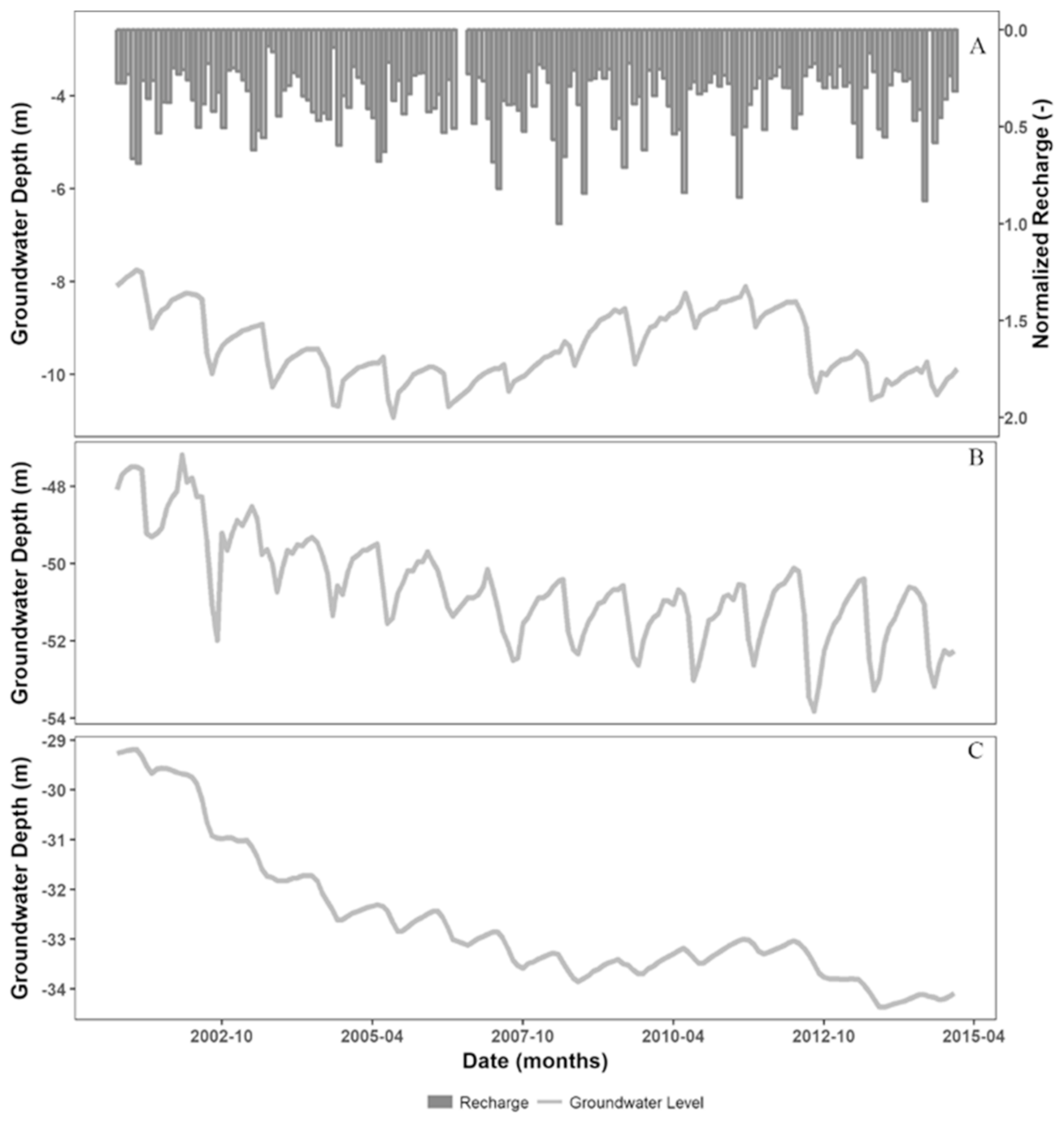

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Clearly Defined Boundaries

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #6. “The COHYST [Cooperative Hydrology Study] group, which stands for the conjunctive cooperative hydrology study group, which involved game and parks, DNR, all the NRDs, the two major irrigation districts, CNPPD and NPPD, kind of make up the COHYST study stuff. The Platte River program headwaters group is somewhat involved as well. We were developing the tools and DNR basically requested that we do the study, the COHYST group. So, we took the groundwater models to COHYST, and they ran all the models to generate the percent depletion by use”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #4. “(T)he NRD didn’t really have much control over the surface water. But then once they established the relationship in the COHYST between how groundwater pumping depletes the surface water. They became much more involved”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #5. “Every 40-acre tract out here has a designated value that they have worked out through this COHYST model that shows the returns and the length of time that…obviously closer to the river water would get back there faster obviously than it would next to the canal...”.

4.2. Appropriation Rules Relevant to Local Conditions

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #6. “Basically, we have an agreement with each of the irrigation districts…. We have a lease agreement to put together the water rights, transfer the water rights. The irrigation district signs them, and we send them in. They total up the bills (for canal repairs) and we go half and half. They pay half and we pay half”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #1. “I think the nice thing about what they are doing is that they have become partners with the surface water folks, who at the beginning of this process, when we started IMP, they were still not partners. They were still thinking everyone was out to get them”.

4.3. Participation by Users

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #8. “Collaboration in this sense was basically, “We will meet with you and take your input.” We were told many times during the (name of NRD redacted) IMP process that the NRD board would make the decisions. We sent in comments. My recollection was that the NRD drafted the IMP and presented it to the stakeholders. In many cases the department responded the same as the stakeholders did. Everyone was feeling their way. There was no set process”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #7. “The statutes say that they are to consult and collaborate with us. Those are two different words. They have two different meanings. And very often what we find is, they come and consult, and they say, “We are consulting and collaborating with you now.” And we would often ask, “Where is the collaboration? Where is the part where you are asking us to be involved with and participate in finding solutions to this? Because it seems like really what you are doing is consulting only”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #9. “And I do know that the water professionals and irrigators came. I think the process would have benefited from a much more educational bent. Because not everyone was on the same level of education on how water works and how this whole thing gets put together. There was very little if I remember it right, very little effort to bring people up to speed with all the stakeholders in fact. And I think I came at it with a fairly decent knowledge, but there was a lot of jargon and acronyms and things like that that probably limited how well people could participate”.

4.4. Monitoring by Users

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #1. “So, there is a reporting and monitoring section in the plan. So basically, the NRD and my department come together and say, “OK here are all the activities that have taken place in the last year” just in a checklist fashion, have we caused more depletions? Are there more accretions? Where are we in the permitting process? And that is telling us on an annual basis are we getting where we want to be”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #2. “What is fully appropriated? Is it where your development is affecting streamflow? These are measures of degree. In our mind, what is that difference? The fact that it wasn’t (fully defined) when all these plans were done was disappointing, and of major concern to us. The difference between fully and over. We still don’t agree with the way the department is proposing to do that. Basically, we are not really allowed to participate any more”.

4.5. Graduated Sanctions

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #1. “The way the law is set up, this first increment, which is 10 years, is that we will get back to 97. So the triggers you see are built to get back to 1997. But there are still shortages in the system just because we are still…well you have drought anyway, and you have wells that have existed before 1997 that are impacting the system as well, and those are not at this point being addressed. The interests in the part of the surface water parties is that those should all be addressed right away. But the plan isn’t set up that way, its set up to do it in incremental fashion, so there is conflict and tension going on there. So it’s not that there isn’t a shortage, it’s that we don’t have to address all the shortage right now”.

4.6. Accessible Conflict Resolution

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #1. “I think it’s going very well. It’s nice to see everyone being very conscientious about what the plan says, and how to be in compliance with that plan. (Name of NRD redacted) has been making great strides to get all those conjunctive management pieces in place. When they started the process, they purchased a lot of easements and buying out groundwater and surface water rights and retiring them. So, they have been a leader in Platte NRDs in implementing various types of practices in getting us to where we need to be”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #7. “Often, we are in disagreement in terms of whether they have actually set something that will actually meet their objective. But it sounds like their objective, their intent, in areas that are not yet fully appropriated…try and identify where they will occur, try and head them off. That’s good. But that’s not really our area. Our concern is they are not really directly trying to resolve the conflict that was already created. We think that there is an obligation to try to do that”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #2. “What is the best way to achieve results then? Is it to get things out there, or just wait 10 years until they get new plans done and then hope we potentially see some change? Then you see lower lake levels. Do you just have to say, ‘I will keep quiet and wait my ten years because that is the only option that is out there?’ We are disappointed in those options”.

Mandatory IMP Interviewee #1. “Well there is the Interrelated Water Review Board. Yeah, that is not if the stakeholders can’t agree, but if the department and the NRD can’t agree what the plan should be. As we go through the stakeholder process even with the consultation and collaboration the statutes clearly say that DNR and NRD can go back and say, ‘OK you guys couldn’t agree, so we are going to see if we are going to agree,’ and so that is where we ended up. We could agree, so we could move forward with that plan even though not all the stakeholders were on board with it”.

4.7. Recognition of Local Rules

4.8. Nested Enterprises

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leuenberger, D.; Reed, C. Social capital, collective action and collaboration. In Advancing Collaboration Theory: Models, Typologies and Evidence; Morris, J., Miller-Stevens, K., Eds.; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleed, A.; Babbitt, C. Nebraska’s Natural Resources Districts: An Assessment of a Large-Scale Locally Controlled Water Governance Framework; Robert, B., Ed.; Daugherty Water for Food Institute: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Ruddell, B.L.; Reed, P.M.; Hook, R.I.; Zheng, C.; Tidwell, V.C.; Siebert, S. The food-energy-water nexus: Transforming science for society. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 3550–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaranto, A.; Munoz-Arriola, F.; Solomatine, D.P.; Corzo, G. A Spatially Enhanced Data-Driven Multimodel to Improve Semiseasonal Groundwater Forecasts in the High Plains Aquifer, USA. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 5941–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaranto, A.; Pianosi, F.; Solomatine, D.; Corzo, G.; Muñoz-Arriola, F. Sensitivity analysis of data-driven groundwater forecasts to hydroclimatic controls in irrigated croplands. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 124957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Munoz-Arriola, F.; Uden, D.R.; Martin, D.; Allen, C.R.; Shank, N. Climate change implications for irrigation and groundwater in the Republican River Basin, USA. Clim. Chang. 2018, 151, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, T.J.; Pavaozuckerman, M.A.; Evans, T.P. Debates-Perspectives on socio-hydrology: Socio-hydrologic modeling: Tradeoffs, hypothesis testing, and validation. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 4806–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cselenyi, M.N. Policy and Management of Water as a Common-Pool Resource in Spain: The Case of the Aquifer’ Carbonatado de la Loma de Úbeda’. Master’s Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; 70p. [Google Scholar]

- Skurray, J.H. The scope for collective action in a large groundwater basin: An institutional analysis of aquifer governance in Western Australia. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickin, S.; Bisung, E.; Savadogo, K. Sanitation and the commons: The role of collective action in sanitation use. Geoforum 2017, 86, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.H.; Edmunds, M.; Lora-Wainwright, A.; Thomas, D. Governance of the irrigation commons under integrated water resources management—A comparative study in contemporary rural China. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, L.A.; Fernandez-Bou, A.S.; Viers, J.H.; Valero-Fandino, J.; Medellín-Azuara, J. A glass half empty: Limited voices, limited groundwater security for California. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 738, 139529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, L.; Cleaver, F.; Mwathunga, E. Flesh and bones: Working with the grain to improve community management of water. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebraska Legislature. Second Regular Session Journal for the 98th Legislature; Nebraska Legislature: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nebraska Water Policy Task Force. Report of the Nebraska Water Policy Task Force to the 2003 Nebraska Legislature; Nebraska Water Policy Task Force: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.; Taylor, J. Water Laws and Policies for a Sustainable Future: A Western States’ Perspective; Western Governors’ Association: Murray, UT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.K.; DuMars, C.T. A survey of the evolution of western water law in response to changing economic and public interest demands. Nat. Resour. J. 1989, 29, 347–387. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.; Weible, C.; Ficker, J. Eras of water management in the United States: Implications for collaborative water-shed approaches. In Swimming Up-Stream: Collaborative Approaches to Watershed Management; Sabatier, P., Focht, W., Lubell, M., Trachtenberg, Z., Vedlitz, A., Matlock, M., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, B.L.; Johnson, P.N.; Segarra, E. Ogallala aquifer depletion: Economic impact on the Texas high plains. Hydrol. Res. 2002, 4, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.; Gupta, D.; Mudliar, P.; Ranjan, P. Adaptive institutions in socio-ecological systems governance: A synthesis framework. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 53, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbitt, C.H.; Burbach, M.; Pennisi, L. A mixed-methods approach to assessing success in transitioning water manage-ment institutions: A case study of the Platte River Basin, Nebraska. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. National Water Information System: USGS Groundwater Data for the Nation. 2015. Available online: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/gw (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Rodell, M.; Houser, P.R.; Jambor, U.E.A.; Gottschalck, J.; Mitchell, K.; Meng, C.-J.; Arsenault, K.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.; Mu, Q.; Zhao, M. MOD16A2 MODIS/Terra Net Evapotranspiration 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V006; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steins, N.A.; Röling, N.; Edwards, V.M. Re-‘Designing’ the Principles: An Interactive Perspective to CPR Theory. Presented at Constituting the Commons: Crafting Sustainable Commons in the New Millenium, the Eighth Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Bloomington, IN, USA, 31 May–4 June 2000; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Amaranto, A.; Munoz-Arriola, F.; Corzo, G.; Solomatine, D.P.; Meyer, G. Semi-Seasonal Groundwater Forecast Using Multiple Data-Driven Models in an Irrigated Cropland. J. Hydroinformatics 2018, 20, 1227–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerling, M.P.; Eischeid, J.K.; Kumar, A.J.; Leung, R.; Mariotti, A.W.A.; Mo, K.; Schubert, S.D.; Seager, R. Causes and Predictability of the 2012 Great Plains Drought. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. A Framework to Analyze the Robustness of Social-ecological Systems from an Institutional Perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkila, T.; Schlager, E.; Davis, M. The role of cross-scale linkages in common pool resource management: Assessing inter-state river compacts. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.; Abdel-Monem, T. Integrated Surface and Groundwater Management in Nebraska: Reconciling Systems of Prior Appropriation and Correlative Rights. Am. Bar Assoc. Sect. Environ. Energy Resour. Water Resour. Comm. Newsl. 2015, 18, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

|

| Boundaries | §46-715(1)(a), §46-715(1)(b), §46-715(2)(b), §46-718(2) | IMPs are mandated in over appropriated or fully appropriated areas as agreed-upon by NeDNR and impacted NRDs. |

| Appropriations | §46-715(2)(c), §46-715(2)(d), §46-715(4), §46-715(5)(c), §46-716(1)(b), §46-716(1)(c), §46 716(1)(d), §46-716(2), §46-718(2), §46-739 | IMP must include one or more controls on both surface and ground water appropriation or use to sustain a balance between hydrologically connected water uses and supplies so that the economic viability, social and environmental health, safety, and welfare of the basin be achieved and maintained. Further, IMPs in over-appropriated basins must identify the amount of water necessary to offset the impact of stream flow depletions initiated after 1997 1. |

| Participation | §46-715(3)(f), §46-715(5)(b), §46-715(5)(d)(ii), §46-717(2), §46-719(3), §46-719(4) | Stakeholder groups must be consulted with during development of the IMP. NeDNR and the NRDs may amend an IMP at annual review, for which there are no provisions for involving stakeholder groups. |

| Monitoring | §46-715(2)(e), §46-715(3)(d), §46-715(5)(d)(ii), §46-715(5)(d)(iii), §46-715(5)(d)(v), §46-715(6) | NeDNR and NRDs jointly progress toward meeting IMP goals and objectives. NeDNR forecasts the maximum water volume from stream flow for beneficial use in both the short and long term. |

| Sanctions | §46-707(1–3), §46-708(3), §46-745(1), §46-745(2)(a), §46-746 (1–2) | NRDs may require reporting, metering or decommission of wells, issue cease and desist orders, initiate lawsuits, and take other forms of action. |

| Conflict Resolution | §46-715(5)(b), §46-718(3), §46-719(2), §46-719(3), §46-719(4) | If the parties reach agreement on the plan, then the NeDNR and the NRD adopt it. NeDNR and NRDs develop and adopt the plan if participating parties disagree. If NeDNR and NRDs are in dispute, the matter may be taken to the Interrelated Water Review Board. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Arriola, F.; Abdel-Monem, T.; Amaranto, A. Common Pool Resource Management: Assessing Water Resources Planning for Hydrologically Connected Surface and Groundwater Systems. Hydrology 2021, 8, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology8010051

Muñoz-Arriola F, Abdel-Monem T, Amaranto A. Common Pool Resource Management: Assessing Water Resources Planning for Hydrologically Connected Surface and Groundwater Systems. Hydrology. 2021; 8(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology8010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Arriola, Francisco, Tarik Abdel-Monem, and Alessandro Amaranto. 2021. "Common Pool Resource Management: Assessing Water Resources Planning for Hydrologically Connected Surface and Groundwater Systems" Hydrology 8, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology8010051

APA StyleMuñoz-Arriola, F., Abdel-Monem, T., & Amaranto, A. (2021). Common Pool Resource Management: Assessing Water Resources Planning for Hydrologically Connected Surface and Groundwater Systems. Hydrology, 8(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology8010051