Spatiotemporal Variation in Land Use/Land Cover and Its Driving Causes in a Semiarid Watershed, Northeastern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

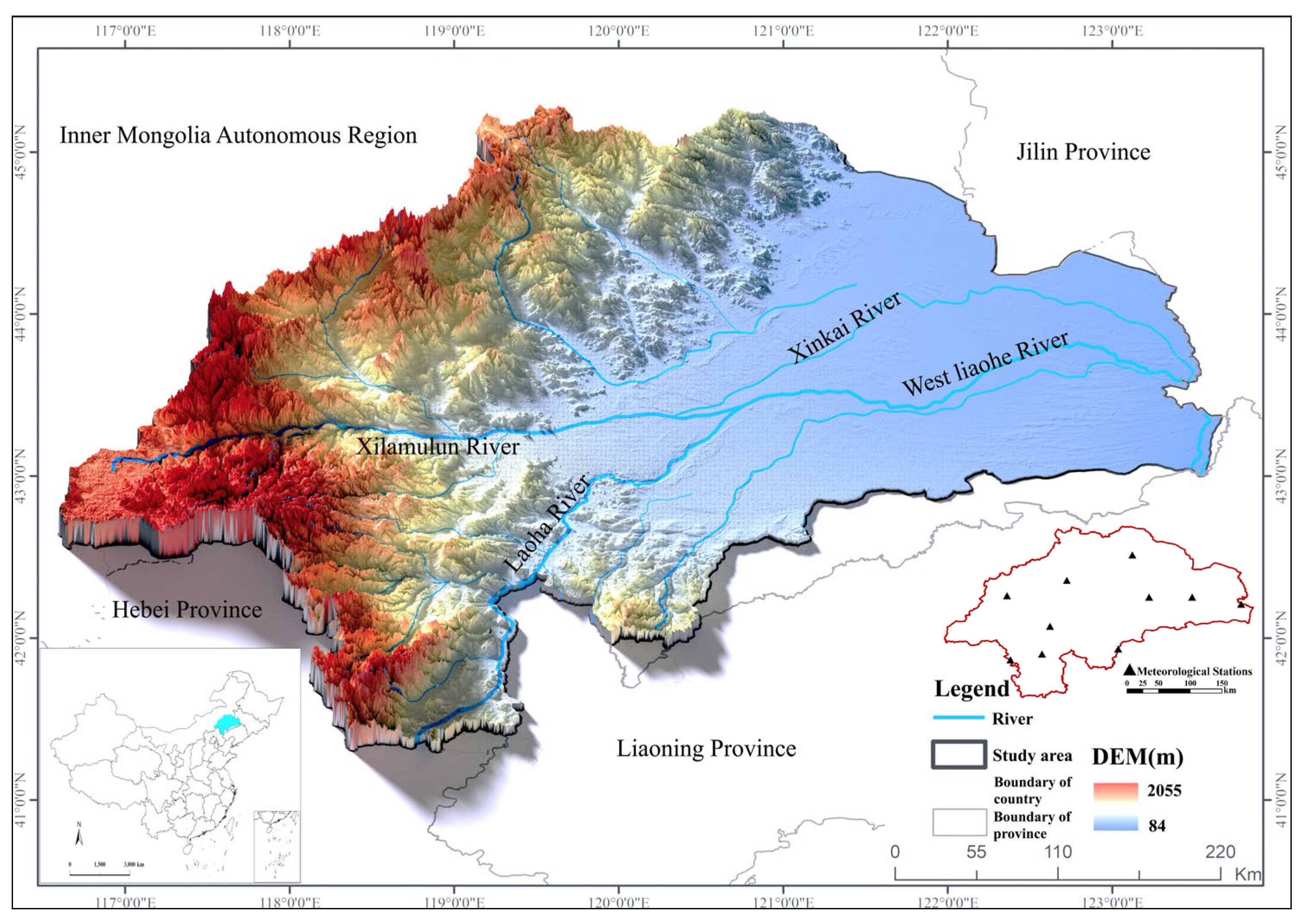

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Land Use Transition Matrix

2.3.2. Landscape Pattern Index

2.3.3. Obstacle Factor Diagnosis

2.3.4. Structural Equation Modeling

3. Results

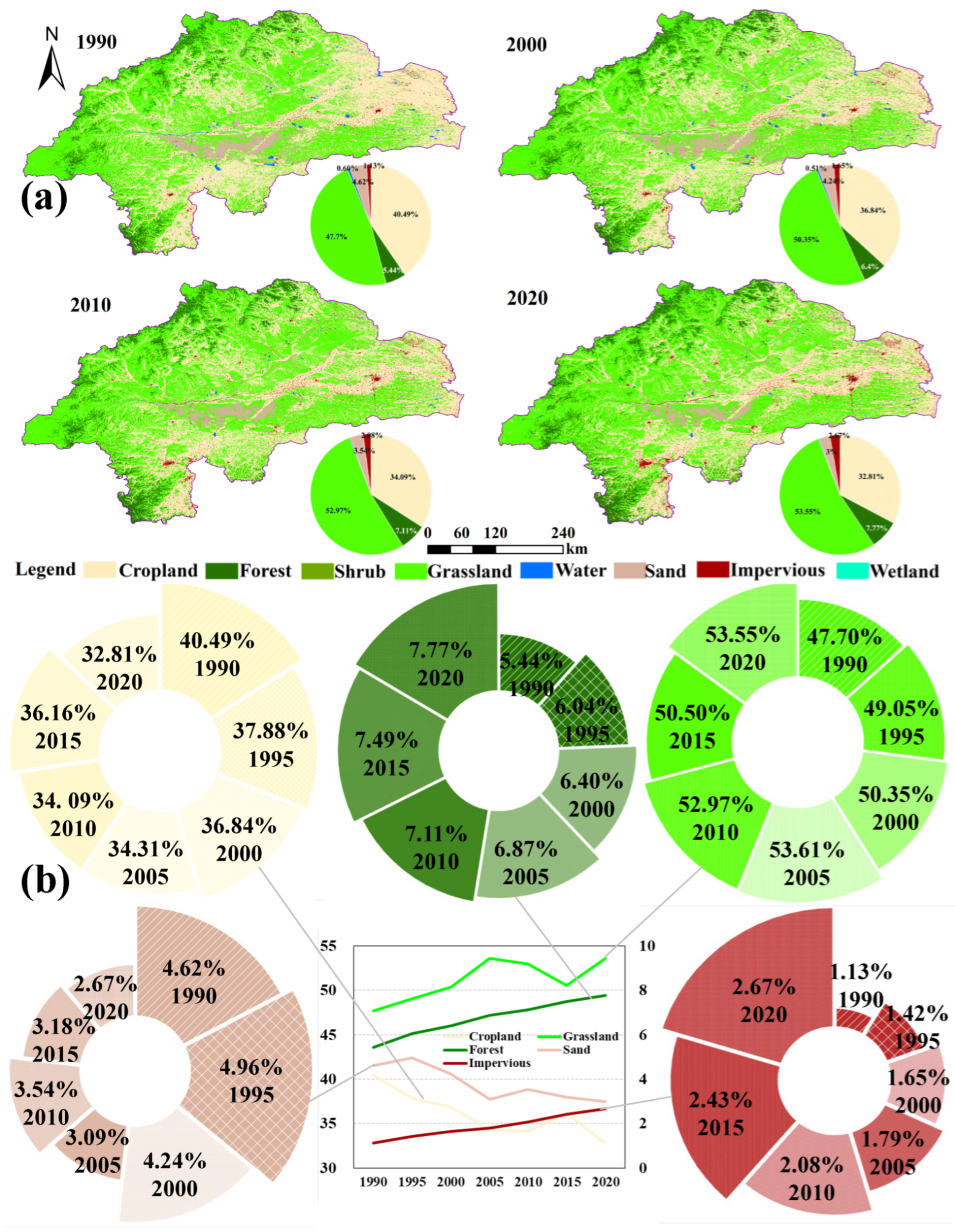

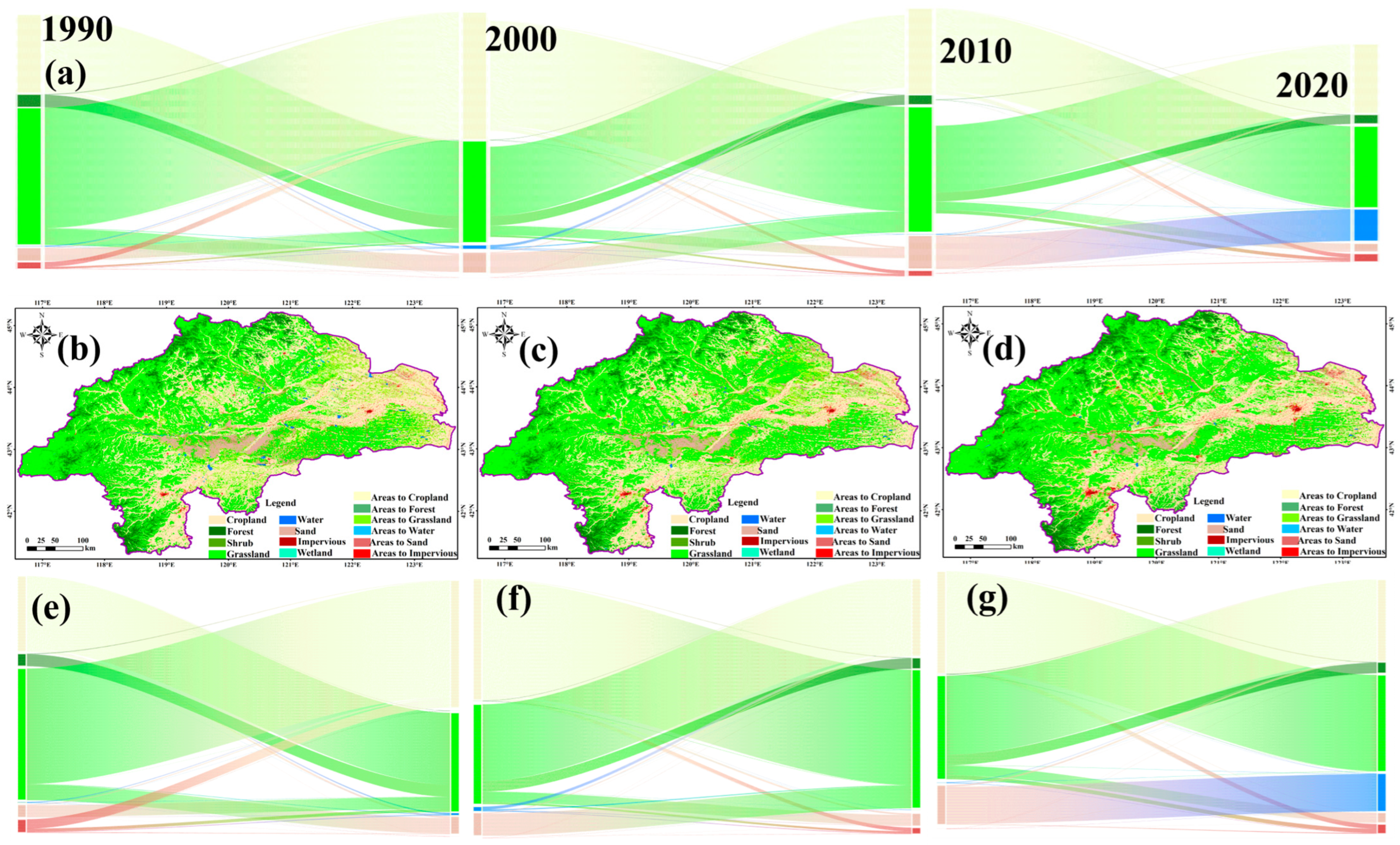

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Land Use/Land Cover in WLRB

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variation in Landscape Pattern Index

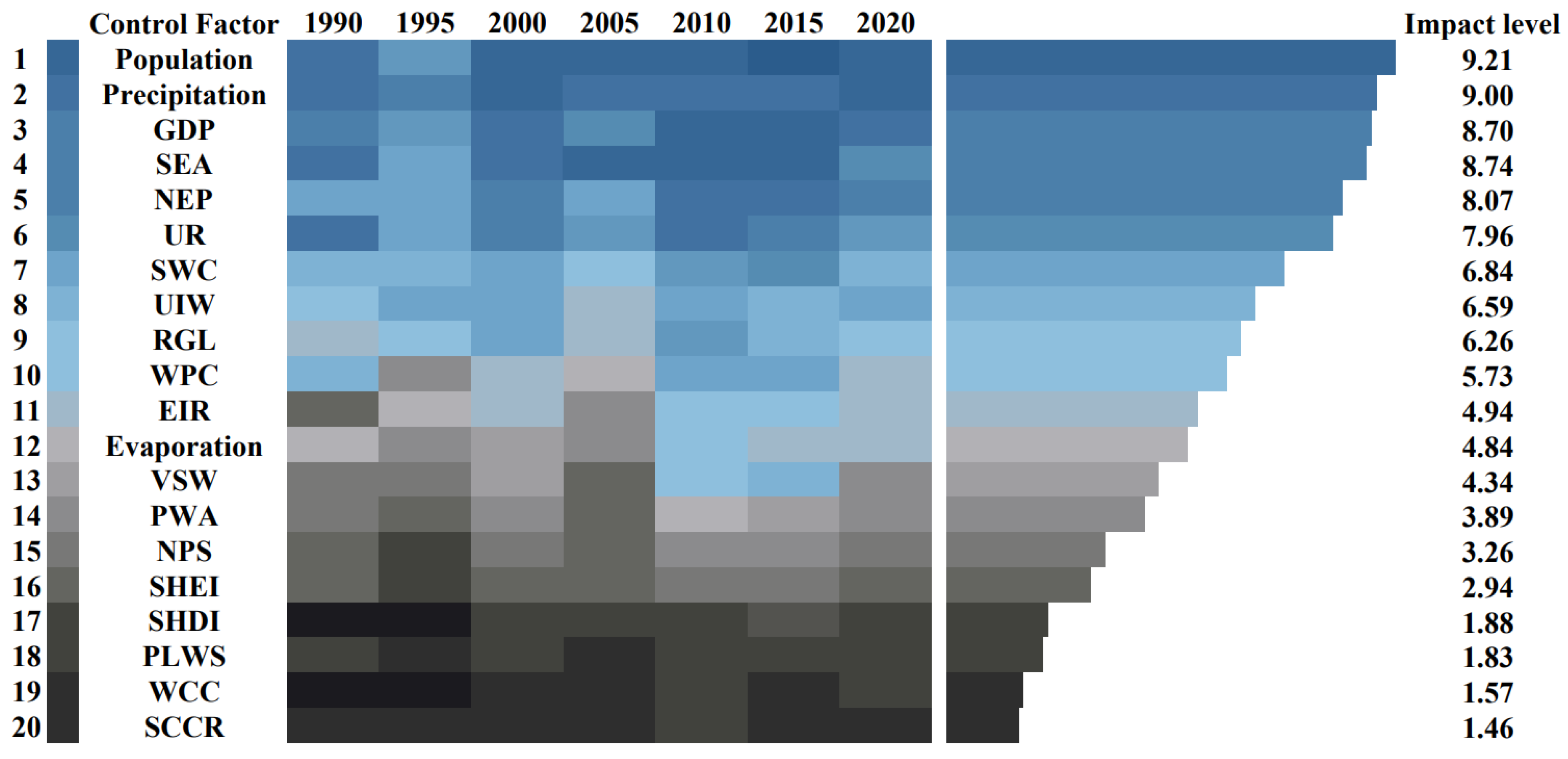

3.3. Obstacle Degree Analysis

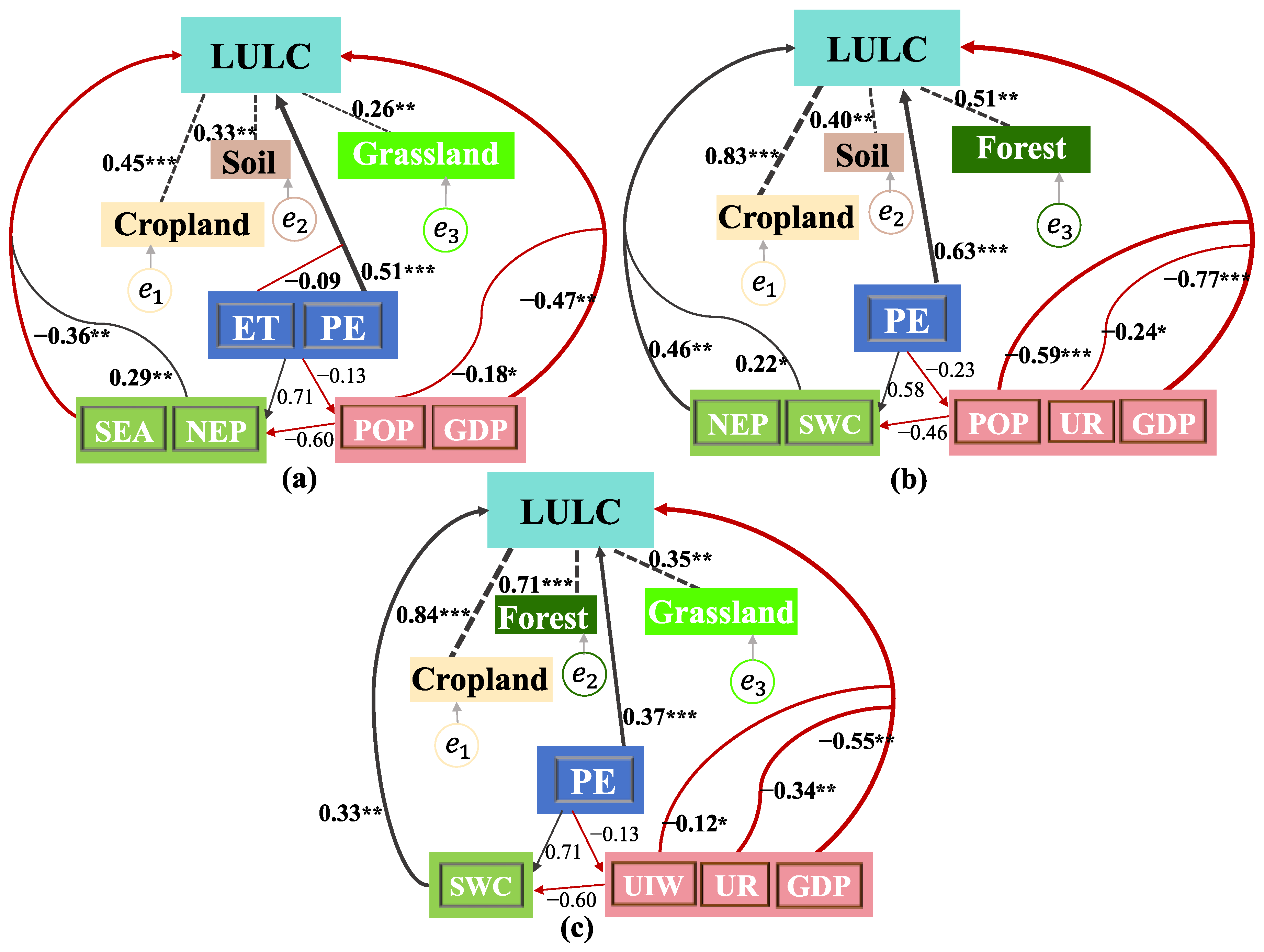

3.4. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Climate Change on Spatiotemporal Variation in LULC

4.2. Effects of Human Activities on Spatiotemporal Variation in LULC

4.3. Effects of Ecological Environment on Spatiotemporal Variation in LULC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Metrics | Abbreviation | Unit | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Landscape | PLAND | Percent | the sum of the areas (m2) of all patches of a patch type | characterize the area and edge metric, with higher values indicating greater landscape integrity and structural continuity |

| Largest Patch Index | LPI | Percent | the proportion of the largest patch in total of a patch type | |

| Edge Density | ED | Meters per hectare | the sum of the lengths of all edge segments in the landscape | |

| Mean Area | AREA_MN | ha | the mean of a patch type area | |

| Fractal Dimension Index | FRAC_AM | None | area-weighted mean of fractal dimension index, quantifies the morphological complexity of patches within a landscape, wherein higher values correspond to more intricate perimeters and greater shape irregularity | |

| Number of Patches | NP | None | total number of patches in the landscape | the aggregation metric, higher NP reflects a heightened degree of fragmentation, lower AI signifies a more dispersed and isolated pattern |

| Aggregation Index | AI | Percent | the degree of aggregation among landscape patches | |

| Shannon’s Diversity Index | SHDI | None | equals minus the sum (across all patch types) of the product of each patch type’s proportional abundance and its own proportion | landscape metric, a rise value is generally considered a marker of enhanced ecosystem structural stability and resilience |

| Shannon’s Evenness Index | SHEI | None | a measurement determined by the distribution of different patch types within a landscape | |

| Data Name | Abbreviation | Year | Data Source | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| soil erosion amount | SEA | 1990–2018 | National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China (http://www.nesdc.org.cn (accessed on 21 November 2023)) | With a resolution of 30 m | t |

| net ecosystem productivity | NEP | 1990–2019 | With a resolution of 8 km | g C m−2day−1 | |

| soil and water conservation ratio | SWC | 1992–2019 | Science Data Bank (https://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.07135 (accessed on 23 November 2023)) | With a resolution of 300 m | t ha−1 a−1 |

| urbanization rate | UR | 1990–2020 | Statistical Yearbook | County and township (22 counties) | % |

| water consumption per unit of industry | UIW | 1990–2020 | m3 10,000 CNY−1 | ||

| effective irrigation rate | EIR | 1990–2020 | % | ||

| water consumption per capita | WCC | 1990–2020 | m3 | ||

| non-point source pollution | NPS | 1990–2020 | t ha−1 a−1 | ||

| water production coefficient | WPC | 1990–2020 | Water Resources Bulletin | Provincial and municipal (22 counties) | % |

| proportion of local water supply | PLWS | 1990–2020 | % | ||

| proportion of water area | PWA | 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | National Geomatics Center of China (http://www.ngcc.cn/ (accessed on 12 March 2022)) | With a resolution of 30 m | m2 |

| Shannon’s evenness index | SHEI | 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | -- | ||

| Shannon’s diversity index | SHDI | 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | -- | ||

| rate of groundwater level decline | RGL | 1990–2020 | Global Land Data Assimilation System (https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/ (accessed on 26 November 2023)) | With a resolution of 25 km (0–10 cm depth) | m a−1 |

| storage capacity change rate | SCCR | 1990–2020 | cm | ||

| volumetric soil water | VSW | 1990–2020 | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis 5 (https://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/ (accessed on 5 December 2023)) | With a resolution of 3 km | m3 m−3 |

References

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, G.; Mund, J.-P. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Land Surface Temperature in Response to Land Use and Land Cover Changes: A Remote Sensing Approach. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; You, L.; Cai, W.; Li, G.; Lin, H. Land Use Projections in China under Global Socioeconomic and Emission Scenarios: Utilizing a Scenario-Based Land-Use Change Assessment Framework. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wan, Q.; Huang, W.; Niu, J. Spatial Heterogeneity Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Land Use Change in Henan Province, China. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2271442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Guhathakurta, S.; Lee, S.; Moore, A.; Yan, L. Grid-Based Land-Use Composition and Configuration Optimization for Watershed Stormwater Management. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 2867–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Tian, H. China’s Land Cover and Land Use Change from 1700 to 2005: Estimations from High-resolution Satellite Data and Historical Archives. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24, 2009GB003687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, M.; Ran, N.; Xie, D.; Wang, Q.; Teng, M.; Wang, P. China’s Key Forestry Ecological Development Programs: Implementation, Environmental Impact and Challenges. Forests 2021, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zhan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Qi, W. Assessment on Forest Carbon Sequestration in the Three-North Shelterbelt Program Region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global Consequences of Land Use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finér, L.; Ohashi, M.; Noguchi, K.; Hirano, Y. Factors Causing Variation in Fine Root Biomass in Forest Ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, W. Ecological Risk Assessment of Land Use Change in the Tarim River Basin, Xinjiang, China. Land 2024, 13, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Tourism-Driven Land Use Transitions and Rural Livelihood Resilience: A Spatial Production Approach to Sustainable Development in China’s Heritage Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Duodu, G.O.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ayoko, G.A. Influence of Land Use Configurations on River Sediment Pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Rong, G.; Han, A.; Riao, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Z. Spatial-Temporal Change of Land Use and Its Impact on Water Quality of East-Liao River Basin from 2000 to 2020. Water 2021, 13, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Hong, M.; Wang, J. Land Resources, Market-Oriented Reform and High-Quality Agricultural Development. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 4165–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kuang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Ning, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Yan, C.; et al. Spatiotemporal Characteristics, Patterns, and Causes of Land-Use Changes in China since the Late 1980s. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betru, T.; Tolera, M.; Sahle, K.; Kassa, H. Trends and Drivers of Land Use/Land Cover Change in Western Ethiopia. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 104, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fang, G.; Xu, Y.-P.; Tian, X.; Xie, J. Identifying How Future Climate and Land Use/Cover Changes Impact Streamflow in Xinanjiang Basin, East China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Deng, R.; Yang, Q. Analysis of Land Use Changes and Driving Forces in the Yanhe River Basin from 1980 to 2015. J. Sens. 2021, 2021, 6692333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, F. Land Use/Cover Change and Its Relationship with Regional Development in Xixian New Area, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Chen, X.; Yao, H.; Lin, F. SWAT Model-Based Quantification of the Impact of Land-Use Change on Forest-Regulated Water Flow. Catena 2022, 211, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, X. Methods for Cropland Reconstruction Based on Gazetteers in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911): A Case Study in Zhili Province, China. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 65, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, G.; Schumacher, M.V.; Momolli, D.R.; Viera, M. Nutrient Input via Incident Rainfall in a Eucalyptus Dunnii Stand in the Pampa Biome. Floresta E Ambiente 2018, 25, e20160559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Xiang, J.; Ling, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, E. Driving Factors of Desertification in Qaidam Basin, China: An 18-Year Analysis Using the Geographic Detector Model. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Yang, M.; Xie, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Lu, X. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving mechanisms of land use/land cover (LULC) changes in the Jinghe River Basin, China. J. Arid. Land 2024, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xin, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. Study of the Intensity and Driving Factors of Land Use/Cover Change in the Yarlung Zangbo River, Nyang Qu River, and Lhasa River Region, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. J. Arid. Land. 2022, 14, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhen, W. Relating Land-Use/Land-Cover Patterns to Water Quality in Watersheds Based on the Structural Equation Modeling. Catena 2021, 206, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Chen, K.; Yang, Y.; Liang, S.; Hu, W.; He, L. Integrative Framework for Decoding Spatial and Temporal Drivers of Land Use Change in Malaysia: Strategic Insights for Sustainable Land Management. Land 2024, 13, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, L.; Yan, Z.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Shi, Y.; Du, Y. Prediction of Ecological Security Network in Northeast China Based on Landscape Ecological Risk. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Shen, W.; Qiu, X.; Chang, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, W. Impact Evaluation of a Payments for Ecosystem Services Program on Vegetation Quantity and Quality Restoration in Inner Mongolia. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Kang, Y.; Han, G.; Sakurai, K. Effect of Climate Change over the Past Half Century on the Distribution, Extent and NPP of Ecosystems of Inner Mongolia: Effect Of Climate Change On The Ecosystem. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Dang, D.; Gong, J.; Wang, H.; Lou, A. Optimizing Landscape Patterns to Maximize Ecological-production Benefits of Water–Food Relationship: Evidence from the West Liaohe River Basin, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3388–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Meng, L.; Liu, P.; Dong, K. Use of a Modified Chloride Mass Balance Technique to Assess the Factors That Influence Groundwater Recharge Rates in a Semi-Arid Agricultural Region in China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, P.; Su, F.; Sun, B.; Liang, L.; Guo, J.; Yang, R. Assessing Ecohydrological Factors Variations and Their Relationships at Different Spatio-Temporal Scales in Semiarid Area, Northwestern China. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 67, 2368–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ren, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, D.; Jiang, S. Hydrological Response to Land Use and Land Cover Changes in a Sub-Watershed of West Liaohe River Basin, China. J. Arid. Land 2014, 6, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, X.; Lyu, X.; Dang, D.; Dou, H.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Cao, W. Optimizing the Land Use and Land Cover Pattern to Increase Its Contribution to Carbon Neutrality. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, S.; Chang, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Qin, T. Research Progress on the Evaluationof Water Resources Carrying Capacity. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Liang, X.; Zhuang, D.; Zheng, K.; Wang, T. Seasonal Variations in CDOM Characteristics and Effects of Environmental Factors in Coastal Rivers, Northeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 29052–29064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m Annual Land Cover Dataset and Its Dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wen, F.; Li, G.; Wang, Y. Coupled Development of the Urban Water-Energy-Food Nexus: A Systematic Analysis of Two Megacities in China’s Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Area. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Ding, G.; Han, Y.; Yi, J.; Guo, J.; Ou, M. Integrated Assessment and Critical Obstacle Diagnosis of Rural Resource and Environmental Carrying Capacity with a Social–Ecological Framework: A Case Study of Liyang County, Jiangsu Province. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 76026–76043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Abebe, S.A.; Dong, B.; Wang, W.; Qin, T. Response of Stream Water Quality to the Vegetation Patterns on Arid Slope: A Case Study of Huangshui River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 9167–9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.; Bocco, G.; Mendoza, M.; Duhau, E. Predicting Land-Cover and Land-Use Change in the Urban Fringe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 55, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Creed, I.F.; Blanco, J.A.; Wei, X.; Sun, G.; Asbjornsen, H.; Bishop, K. Forest Water-Use Efficiency: Effects of Climate Change and Management on the Coupling of Carbon and Water Processes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 534, 120853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A.; Neel, M.C.; Ene, E. Fragstats: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps. 2002. Available online: www.umass.edu/landeco/research/fragstats/fragstats.html (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Deng, J.S.; Wang, K.; Hong, Y.; Qi, J.G. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics and Evolution of Land Use Change and Landscape Pattern in Response to Rapid Urbanization. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2009, 92, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, M. Driving Forces behind the Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change: A Case Study of the Weihe River Basin, China. J. Arid. Land 2023, 15, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Chen, H.; Ju, W.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Fang, Y. Effects of Climate Change on Annual Streamflow Using Climate Elasticity in Poyang Lake Basin, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 112, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Pang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, D.; Li, Y.; An, Z.; Jin, L. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Land Use Change Characteristics in the Upper Watershed Area of the Qingshui River Basin from 1990 to 2020. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1388058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhao, X.; He, J.; Ji, D.; Wang, W. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Dynamic Evolution Characteristics and Driving Forces of Land Use/Cover Change in the Weihe River Basin in the Past 30 Years. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 7106–7118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Xue, P.; Gong, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Effects of Land Use Patterns on the Interannual Variations of Carbon Sinks of Terrestrial Ecosystems in China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, G.; Abera, W.; Tamene, L.; Amede, T. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Land Management Practices and Land Uses on Soil Loss in Ethiopia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Seasonally Disparate Responses of Surface Thermal Environment to Land Use/Land Cover Patterns: A Case Study of Central Urban Area of Jinan City, China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2025, 69, 2983–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, F.; Guo, J. Historical Grassland Desertification Changes in the Horqin Sandy Land, Northern China (1985–2013). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shang, Z.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Jia, B.; Liu, J.; Ren, H.; Zhu, Y. Spatiotemporal Variation of Vegetation Cover and Land Use in the Upper Xiliao River Basin and Its Impact on River Sediment Concentration. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2025, 1–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mganga, K.Z.; Musimba, N.K.R.; Nyariki, D.M.; Nyangito, M.M.; Mwang’ombe, A.W. The Choice of Grass Species to Combat Desertification in Semi-arid Kenyan Rangelands Is Greatly Influenced by Their Forage Value for Livestock. Grass Forage Sci. 2015, 70, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X. Evaluation of Soil Loss Change after Grain for Green Project in the Loss Plateau: A Case Study of Yulin, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Ouyang, Z. Responses of Landscape Structure to the Ecological Restoration Programs in the Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Song, M.; Han, F. Urban Economic Structure, Technological Externalities, and Intensive Land Use in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Yeboah, E.; Koo, H.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F.; Sieber, S.; Fürst, C. Participatory and Spatially Explicit Assessment to Envision the Future of Land-Use/Land-Cover Change Scenarios on Selected Ecosystem Services in Southwestern Ghana. Environ. Manag. 2024, 74, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung’u, G.N.; Cousseau, L.; Githiru, M.; Habel, J.C.; Kinyanjui, M.; Matheka, K.; Schmitt, C.B.; Seifert, T.; Teucher, M.; Lens, L.; et al. Anthropogenic Activities Affect Forest Structure and Arthropod Abundance in a Kenyan Biodiversity Hotspot. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 3255–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.K.; Alan Blackburn, G.; Duncan Whyatt, J. Developing the Desert: The Pace and Process of Urban Growth in Dubai. Comput. Environ. Urban 2014, 45, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droomers, M.; Jongeneel-Grimen, B.; Bruggink, J.-W.; Kunst, A.; Stronks, K. Is It Better to Invest in Place or People to Maximize Population Health? Evaluation of the General Health Impact of Urban Regeneration in Dutch Deprived Neighbourhoods. Health Place 2016, 41, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, W.; Shi, W. Progress on Quantitative Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Cropland Change. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhu, P.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, R. Dynamic Aeolian Erosion Evaluation and Ecological Service Assessment in Inner Mongolia, Northern China. Geoderma 2022, 406, 115518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. China’s Forest Carbon Sinks and Mitigation Potential from Carbon Sequestration Trading Perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogunović, I.; Kovács, P.G.; Ðekemati, I.; Kisić, I.; Balla, I.; Birkás, M. Long-Term Effect of Soil Conservation Tillage on Soil Water Content, Penetration Resistance, Crumb Ratio and Crusted Area. Plant Soil Environ. 2019, 65, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, W.; Miao, C. Hydrogeomorphic Ecosystem Responses to Natural and Anthropogenic Changes in the Loess Plateau of China. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 45, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Name | Year | Data Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | 1990–2020 | China Meteorological Data Service Center (http://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 9 August 2023)) | Daily data from 10 meteorological stations |

| Evaporation | |||

| Population | 1990–2020 | Statistical Yearbook | County and township (22 counties) |

| GDP | |||

| Industry structures | |||

| Land use | 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | National Geomatics Center of China (http://www.ngcc.cn/ (accessed on 12 March 2022)) | With a resolution of 30 m |

| Water Resources | 1990–2020 | Water Resources Bulletin | Provincial and municipal (22 counties) |

| Soil Moisture | 1990–2020 | Global Land Data Assimilation System (https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/ (accessed on 20 November 2023)) | With a resolution of 25 km (0–10 cm depth) |

| Types | Year | PLAND | LPI | ED | AREA_MN | FRAC_AM | NP | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropland | 1990 | 33.83 | 16.18 | 17.12 | 201.10 | 1.3182 | 9071 | 92.41 |

| 2010 | 31.98 | 15.02 | 17.40 | 161.51 | 1.3105 | 10,676 | 91.84 | |

| 2020 | 29.89 | 13.00 | 17.53 | 137.91 | 1.3045 | 11,685 | 91.21 | |

| Forest | 1990 | 22.82 | 0.73 | 41.16 | 10.59 | 1.299 | 116,239 | 72.92 |

| 2010 | 23.19 | 1.13 | 40.84 | 10.27 | 1.2974 | 121,798 | 73.56 | |

| 2020 | 24.00 | 1.40 | 40.25 | 10.92 | 1.2968 | 118,523 | 74.82 | |

| Grassland | 1990 | 38.21 | 15.05 | 49.95 | 21.94 | 1.3598 | 93,883 | 80.36 |

| 2010 | 38.79 | 15.44 | 49.51 | 22.26 | 1.3669 | 93,955 | 80.83 | |

| 2020 | 37.83 | 14.44 | 48.41 | 22.23 | 1.3617 | 91,758 | 80.77 | |

| Water | 1990 | 1.917 | 1.10 | 1.32 | 14.33 | 1.1674 | 7215 | 89.39 |

| 2010 | 2.09 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 26.72 | 1.1754 | 4213 | 91.84 | |

| 2020 | 1.96 | 0.55 | 1.12 | 44.40 | 1.1637 | 2382 | 91.19 | |

| Impervious | 1990 | 2.89 | 0.11 | 3.24 | 25.68 | 1.1064 | 6077 | 83.23 |

| 2010 | 3.65 | 0.24 | 3.65 | 26.34 | 1.1112 | 7472 | 85.02 | |

| 2020 | 5.80 | 0.29 | 5.53 | 33.91 | 1.1363 | 9227 | 85.69 | |

| Sandy land | 1990 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 2.20 | 1.1305 | 8034 | 56.02 |

| 2010 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 1.98 | 1.1241 | 8381 | 53.33 | |

| 2020 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 3.91 | 1.1247 | 7193 | 71.50 |

| Year | NP | LPI | ED | AREA_MN | CONTAG | SHDI | SHEI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 240,519 | 16.1849 | 56.8831 | 22.4185 | 53.7181 | 1.2685 | 0.7080 |

| 2010 | 246,495 | 15.4432 | 56.7293 | 21.8757 | 53.042 | 1.2902 | 0.7201 |

| 2020 | 240,768 | 14.4353 | 56.9253 | 22.3957 | 47.2524 | 1.3409 | 0.7484 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Li, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, H.; Qin, T. Spatiotemporal Variation in Land Use/Land Cover and Its Driving Causes in a Semiarid Watershed, Northeastern China. Hydrology 2026, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010042

Li J, Li W, Gao H, Liu H, Qin T. Spatiotemporal Variation in Land Use/Land Cover and Its Driving Causes in a Semiarid Watershed, Northeastern China. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jian, Weizhi Li, Haoyue Gao, Hanxiao Liu, and Tianling Qin. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Variation in Land Use/Land Cover and Its Driving Causes in a Semiarid Watershed, Northeastern China" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010042

APA StyleLi, J., Li, W., Gao, H., Liu, H., & Qin, T. (2026). Spatiotemporal Variation in Land Use/Land Cover and Its Driving Causes in a Semiarid Watershed, Northeastern China. Hydrology, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010042