Modeling Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds for Flood Early Warning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Model Concept

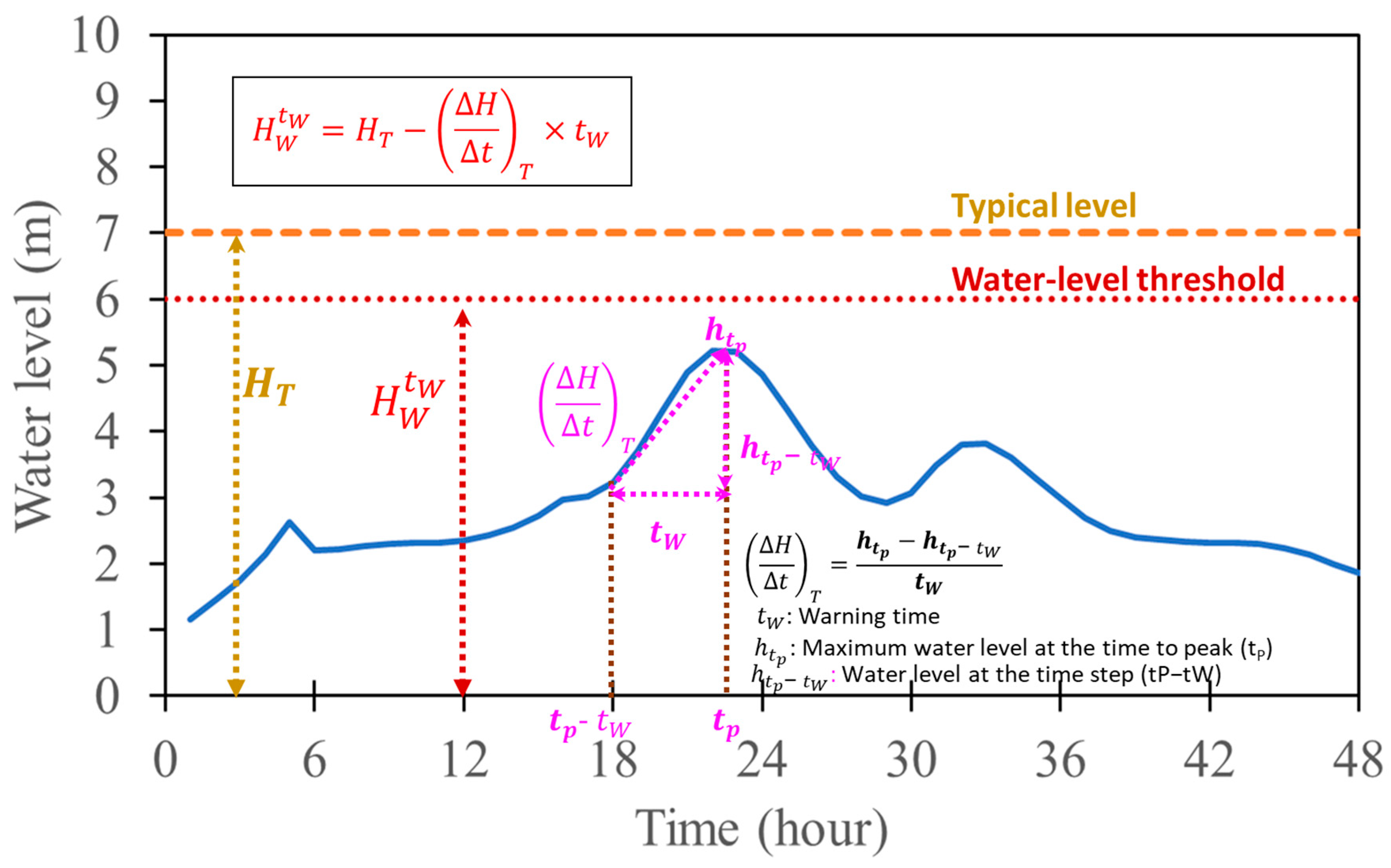

2.2. Estimation of River-Based Water-Level Thresholds

2.3. Simulation of Rainfall-Induced River Stages

2.4. Identification of Uncertainty Factors Subject to River-Based Water-Level Thresholds

2.5. Reliability Quantification of River-Based Water-Level Thresholds

2.5.1. Advanced First-Order and Second-Moment AFOSM

2.5.2. Logistic Regression Equation

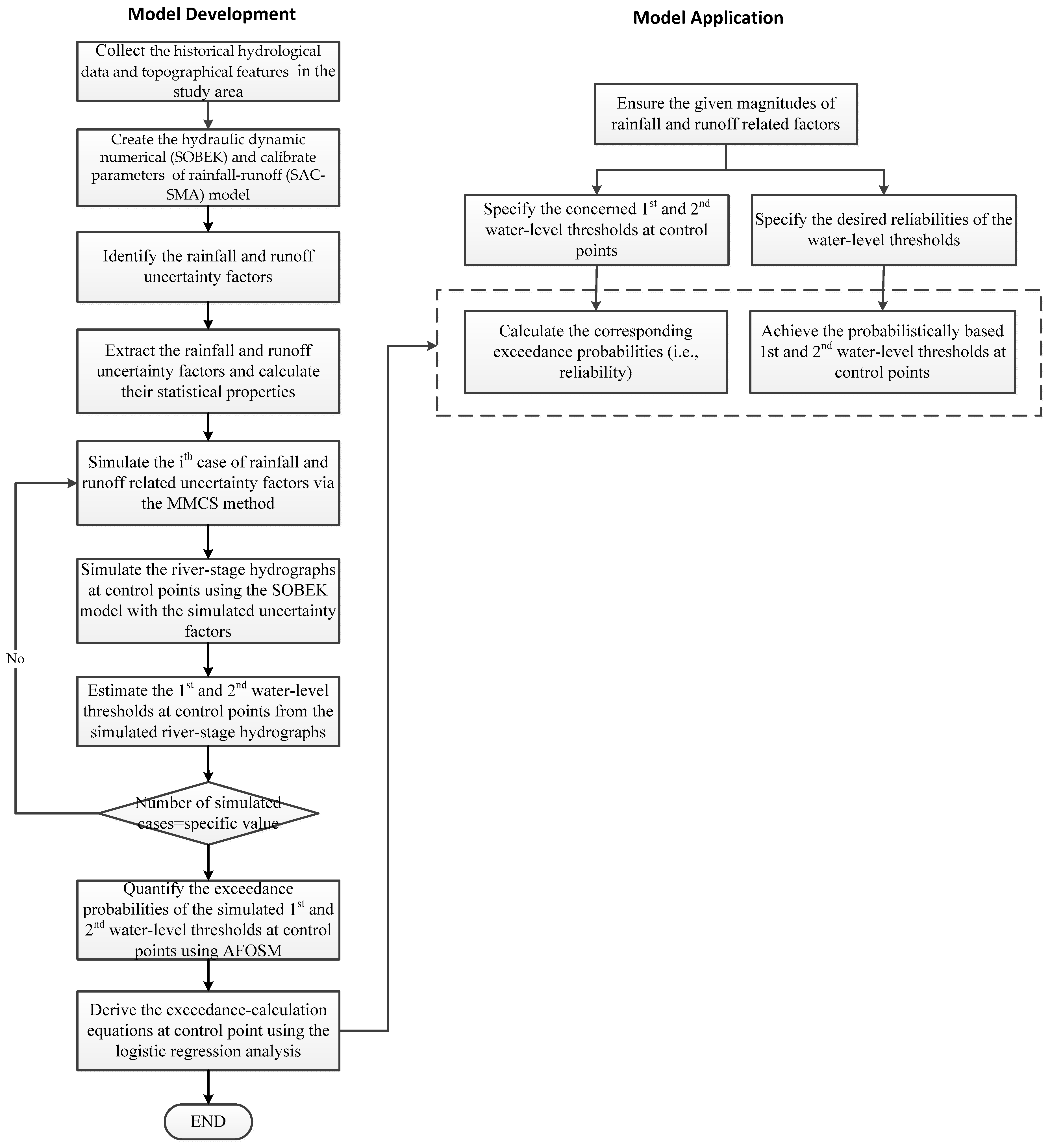

2.6. Model Framework

2.6.1. Model Development

2.6.2. Model Application

3. Materials

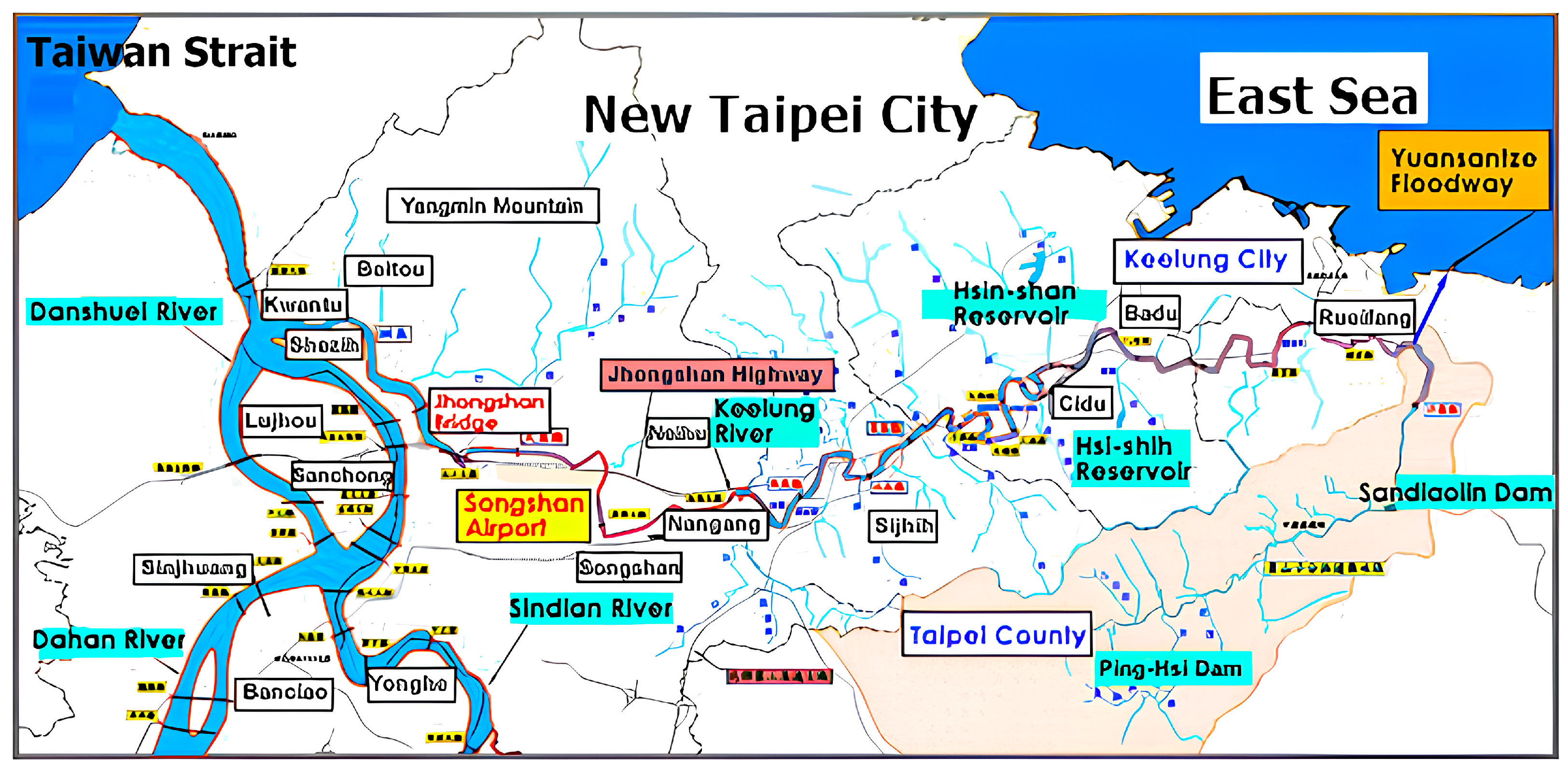

3.1. Study Area

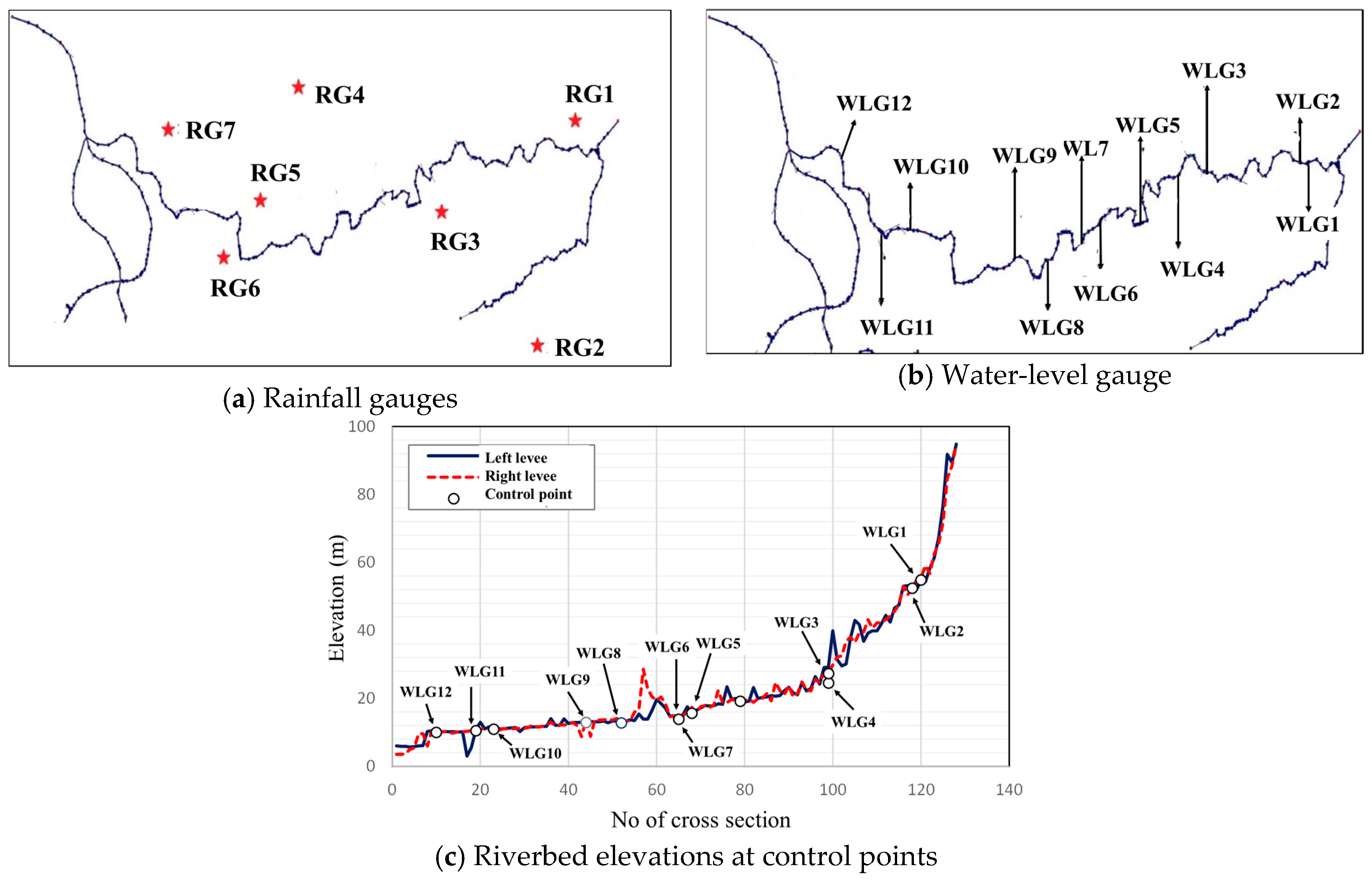

3.2. Study Data

3.2.1. Rainfall-Related Factors

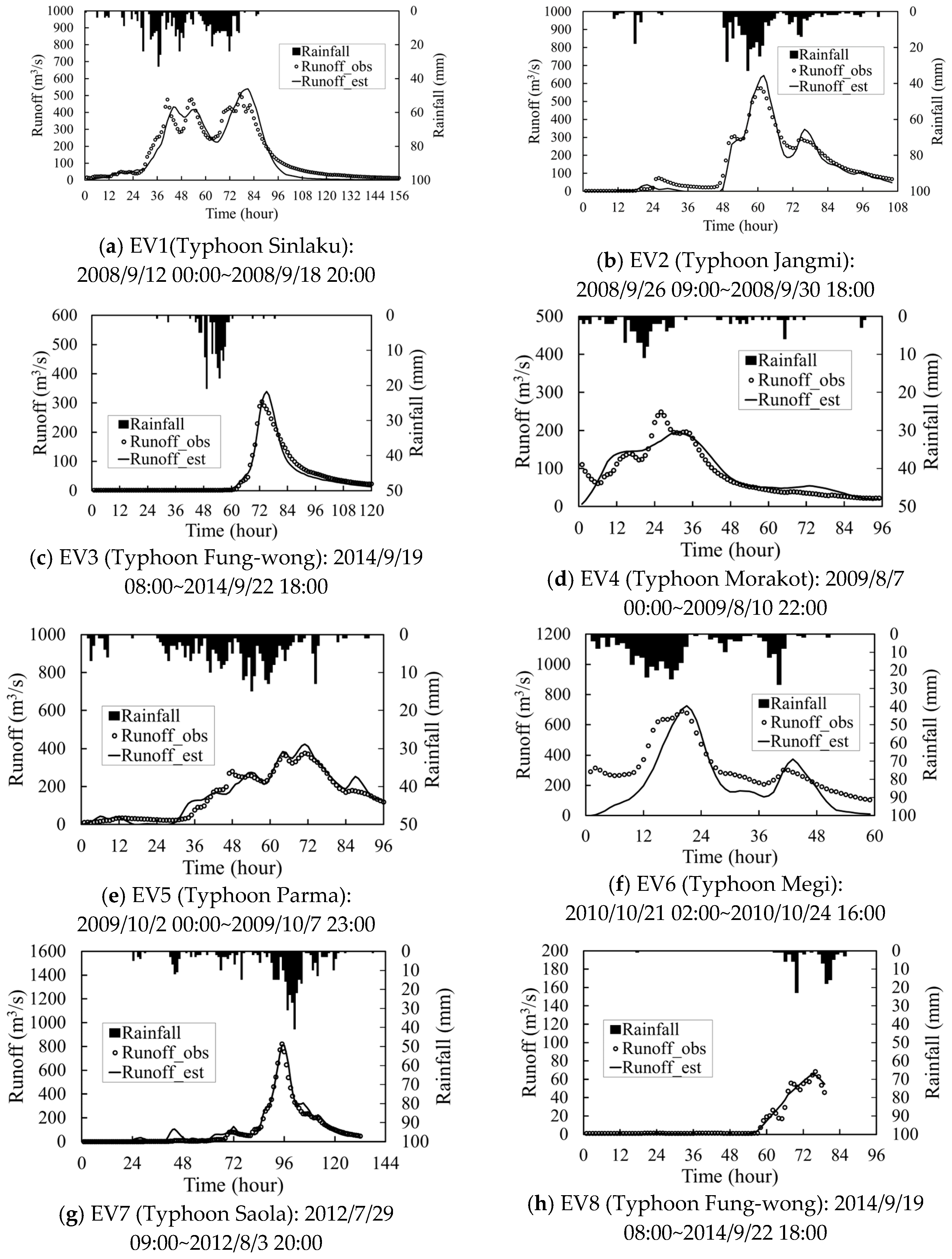

3.2.2. Runoff-Related Factors

- (1)

- SAC-SMA parameters

- (2)

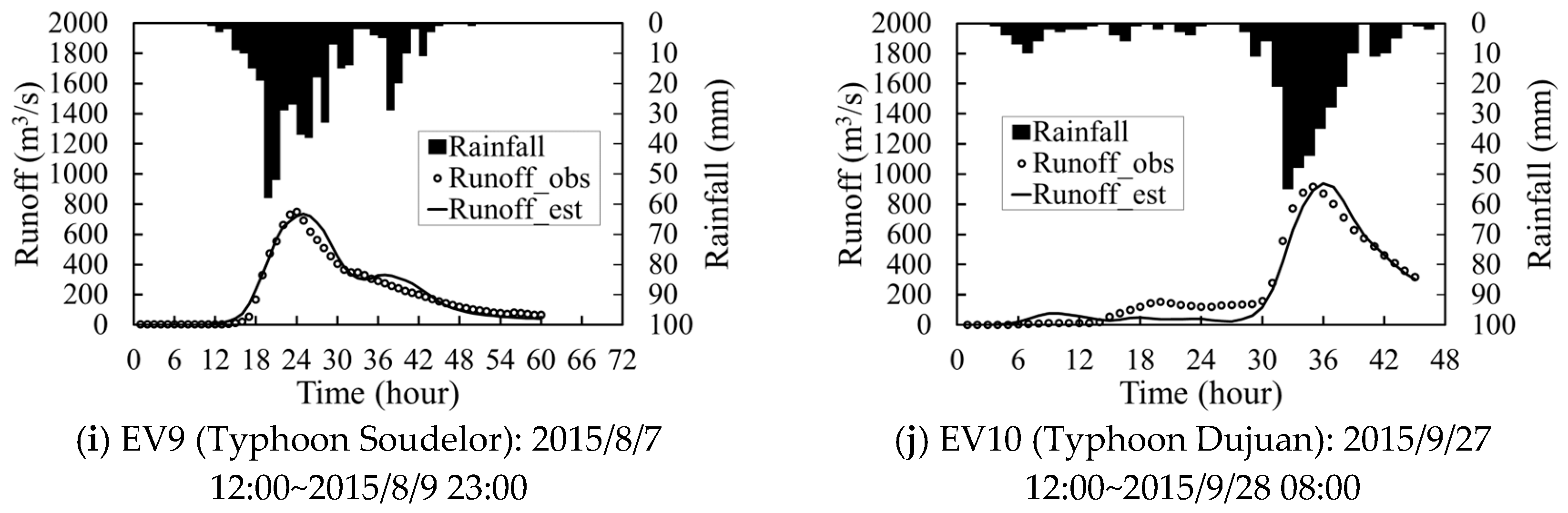

- River-channel roughness

- (3)

- Tide depth

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Simulation and Evaluation of the First and Second Water-Level Thresholds

4.2. Derivation of the Proposed RA_WLTE_River Model

4.2.1. Establishment of the Water-Level Threshold Relationship with Uncertainty Factors

4.2.2. Reliability Quantification and Assessment of Water-Level Thresholds

4.2.3. Derivation of the Exceedance Probability Calculation

4.3. Application of the Proposed RA_WLTE_River Model on Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds

4.3.1. Historical Data

4.3.2. Design Data

4.4. Estimation of the Probabilistically Based Water-Level Thresholds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Guan, X.; Lv, H.; Yan, D. Study on urban flood early warning system considering flood loss. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Perez, R.; García-Pintado, J.; Gómez, A.S. A real-time measurement system for long-life flood monitoring and warning applications. Sensors 2012, 12, 4213–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H. An advanced method to apply multiple rainfall thresholds for urban flood warnings. Water 2015, 7, 6056–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Hsu, C.T.; Lien, H.C.; Chang, C.H. Modeling the effect of uncertainties in rainfall characteristics on flash flood warning based on rainfall thresholds. Nat. Hazards 2015, 75, 1677–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.H.W.; Jidin, A.Z.; Aziz, S.A.C.; Rahim, N. Flood disaster indicator of water level monitoring system. Int. J. Comput. Eng. 2019, 19, 1694–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, S. Analysis of the specific water level of flood control and the threshold value of rainfall warning for small and medium rivers. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2020, 383, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufuoma, G.; Sasanya, B.F.; Abaje, P.; Awodutire, P. Efficiency of camera sensors for flood monitoring and warnings. Sci. Afr. 2021, 13, e00887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis GdCd Pereira, T.S.R.; Faria, G.S.; Formiga, K.T.M. Analysis of the Uncertainty in Estimates of Manning’s Roughness Coefficient and Bed Slope Using GLUE and DREAM. Water 2020, 12, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Briggs, M.A.; Foks, S.S.; Goodling, P.J.; Raffensperger, J.P.; Rosenberry, D.O.; Scholl, M.A.; Tiedeman, C.R.; Webb, R.M. Uncertainties in measuring and estimating water-budget components: Current state of the science. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2023, 10, e1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Zhao, Y.W.; Chau, K.W.; Xu, D.M.; Liu, C.J. Improving flood forecasting using geomorphic unit hydrograph based on spatially distributed velocity field. J. Hydroinform. 2021, 123, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Hsu, C.T.; Shen, J.C.; Chang, C.H. Modeling the 2D Inundation Simulation Based on the ANN-Derived Model with Real-Time Measurements at Roadside IoT Sensors. Water 2022, 14, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, L.; Tang, W.; Xu, W.; Tian, J.; Lyu, G. Study on Dynamic Early Warning of Flash Floods in Hubei Province. Water 2023, 15, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shi, X.; Liu, Q.; Tan, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, H. Warning water level determination and its spatial distribution in coastal areas of China. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Zhao, Y.W.; Xu, D.M.; Hong, Y.G. Error correction method based on deep learning for imporving the accuracy of conceptual rainfall runoff model. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 131992. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, D.; Alam, J.; Umeda, K.; Hayashi, M.; Hironaka, S. A two-dimensional hydrodynamic model for flood inundation simulation: A case study in the lower Mekong river basin. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.A.; Gourley, J.J.; Flamig, Z.L.; Hong, Y.; Clark, E. CONUS-wide evaluation of national weather service flash flood guidance products. Weather. Forecast. 2014, 29, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Liang, Q.; Xia, X.; Li, D.; Fowler, H.J. Real-time flood forecasting based on a high-performance 2-D hydrodynamic model and numerical weather predictions. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimisetty, S.; Singh, A.; Venkata, D.R.K.H. 1D and 2D model coupling approach for the development of operational spatial flood early warning system. Geocarto Int. 2021, 37, 4390–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg, B.; Suligowski, R.; Drewnowski, J.; De Paola, F.; Fernandez-Morales, F.J.M.; Bask, L. Simulation of the number of storm overflows considering changes in precipitation dynamics and the urbanization of the catchment area: A probabilistic approach. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulos, G.; Panagiotatou, E.; Sant, V.; Baltas, E.; Diakakis, M.; Lekkas, W.; Stamou, A. Optimizing the Performance of Coupled 1D/2D Hydrodynamic Models for Early Warning of Flash Floods. Water 2022, 14, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseiny, H. A deep learning model for predicting river flood depth and extent. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 145, 105186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xia, W.; Shoemaker, C.A. Surrogate global optimization for identifying cost-effective green infrastructure for urban flood control with a computationally expensive inundation model. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedi, M.A.A.; Smith, V.; Hosseiny, H.; Jiao, X. Unraveling the complexities of urban fuvial food hydraulics through AI. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bout, B.V.D.; Jetten, V.G.; van Westen, C.J.; Lombardo, L. A breakthrough in fast flood simulation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 168, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.D.; Chen, W.B.; Yeh, S.H.; Chang, C.H.; Chen, H. Prediction of River Stage Using Multistep-Ahead Machine Learning Techniques for a Tidal River of Taiwan. Water 2021, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isizoh, A.H.; Nwani, E.M.; Onyia, T.C.; Eze, C.E.; Okeke, N.P. Real-Time Flood Monitoring and Early Warning System Using Artificial Intelligence Technique. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2021, 3, 2287–2300. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, P.; Orellana-Alvear, J.; Bendix, J.; Feyen, J.; Celleri, R. lood Early Warning Systems Using Machine Learning Techniques: The Case of the Tomebamba Catchment at the Southern Andes of Ecuador. Hydrology 2021, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.; Li, D.; Li, W.; Fang, Z. Data-driven flood alert System (FAS) Using extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) to forecast flood stages. Water 2022, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Yoon, S.; Moon, Y. Urban flood forecasting using a hybrid modeling approach based on a deep learning technique. J. Hydroinform. 2023, 25, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adikari, K.E.; Shrestha, S.; Ratnayake, D.; Budhathoki, A.; Mohanasundaram, S.; Dailey, M.N.; Budhathoki, A.; Mohanasundaram, S.; Dailey, M.N. valuation of artificial intelligence models for flood and drought forecasting in arid and tropical regions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 144, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Hsu, C.T.; Chang, C.H. Stochastic modeling of gridded short-term rainstorms. Hydrol. Res. 2021, 52, 876–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Azamathulla, H.M.; Sharma, K.V.; Mehta, D.J.; Maharaj, K.T. The State of the Art in Deep Learning Applications, Challenges, and Future Prospects: A Comprehensive Review of Flood Forecasting and Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauswirth, S.M.; van der Wiel, K.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; Beijk, V.; Wanders, N. Simulating hydrological extremes for different warming levels–combining large scale climate ensembles with local observation based machine learning models. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Yang, J.C.; Tung, Y.K. Risk analysis for flood-control structure under consideration of uncertainties in design flood. Nat. Hazards 2011, 58, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Yang, J.C.; Tung, Y.K. Incorporate marginal distributions in point estimate methods for uncertainty analysis. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1997, 123, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Yeh, K.C. Establishment and Practical Application of Flood Warning Stage in Taiwan’s River. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2017, 19, EGU2017-8219. [Google Scholar]

- Deltares systems. SOBEK 1D/2D modelling suite for integral water solutions User Manual; Delftares: Delft, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://content.oss.deltares.nl/sobek2/SOBEK_User_Manual.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Wu, S.J.; Lien, H.C.; Chang, C.H. Calibration of Conceptual Rainfall-Runoff Model using Genetic Algorithm Integrated with Runoff Estimation sensitivity to parameters. J. Hydroinform. 2012, 14, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.K.; Yeh, K.C. Evaluation of safety of hydraulic structures affected by migrating pits. Stoch. Hydrol. Hydraulic. 1993, 7, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.K.; Yen, B.C. Hydrosystems Engineering Uncertainty Analysis; McGrqw-Hill Company: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ganji, A.; Jowkarshorijeh, L. Advance first order second moment (AFOSM) method for single reservoir operation reliability analysis: A case study. Stoch. Environ. Risk Assess. 2012, 26, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel-Martin, I.; Sordo-Ward, A.; Garrote, L.; Castillo, L.G. Influence of initial reservoir level and gate failure in dam safety analysis. Stochastic approach. J. Hydrol. 2017, 550, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.K. Uncertainty and reliability analysis in water resources engineering. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2011, 103, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, B. Scenario-based real-time flood prediction with logistic regression. Water 2021, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, C.; Yu, H.; Zhou, W.H.; Peng, S. Quantitative evaluation of life loss induced by embankment failure with the impact of riverbed deformation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 120, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.J.; Lien, H.O.; Chang, C.H. Modeling risk analysis for forecasting peak discharge during flooding prevention and warning operation. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2010, 24, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakuma, B.; Singh, V.P. Hydrologic system complexity and nonlinear dynamic concepts for a catchment classification framework. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2022, 8, 4427–4458. [Google Scholar]

- Higashino, M.; Stefan, H. Variability and change of precipitation and flood discharge in a Japanese river basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2019, 21, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; He, D.; Liu, S.; Ji, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H. Novel time-lag informed deep learning framework for enhanced streamflow prediction and flood early warning in large-scale catchments. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyaripor, F.; Faraji-Ashkavar, S.; Koohyian, F.; Tang, Q.; Noori, R. Annual flood damage influenced by El Niño in the Kan River basin, Iran. Nat. Harards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasali, F.; Tawalbeh, R.T.; Ghanem, Z.; Mohammad, F.; Alghazzawi, M. A Sustainable Early Warning System Using Rolling Forecasts Based on ANN and Golden Ratio Optimization Methods to Accurately Predict Real-Time Water Levels and Flash Flood. Sensor 2021, 21, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sušanj Cule, I.; Ožani’c, N.; Volf, G.; Karleuša, B. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Water-Level Prediction Model as a Tool for the Sustainable Management of the Vrana Lake (Croatia) Water Supply System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Description |

|---|---|

| UZTWM | Upper-zone tension water capacity (mm) |

| UZFWM | Upper-zone free water capacity (mm) |

| UZK | Upper-zone recession coefficient |

| PCTIM | Percent of impervious area |

| ADIMP | Percent of additional impervious area |

| ZPERC | Minimum percolation rate coefficient |

| REXP | Percolation equation exponent |

| LZTWM | Lower-zone tension water capacity (mm) |

| DF_L | Period of runoff distribution function |

| DF_P | Maximum ratio of the runoff distribution function |

| Hydrological Analysis Adopted | Uncertainty Factor | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Rainfall–runoff and 1D river-stage routing | Rainfall-related factor | Rainfall duration |

| Rainfall depth | ||

| Storm pattern | ||

| Runoff-related factor | Parameters of the rainfall–runoff (SAC-SAM) model | |

| Tide depth | ||

| Riverbed roughness coefficient |

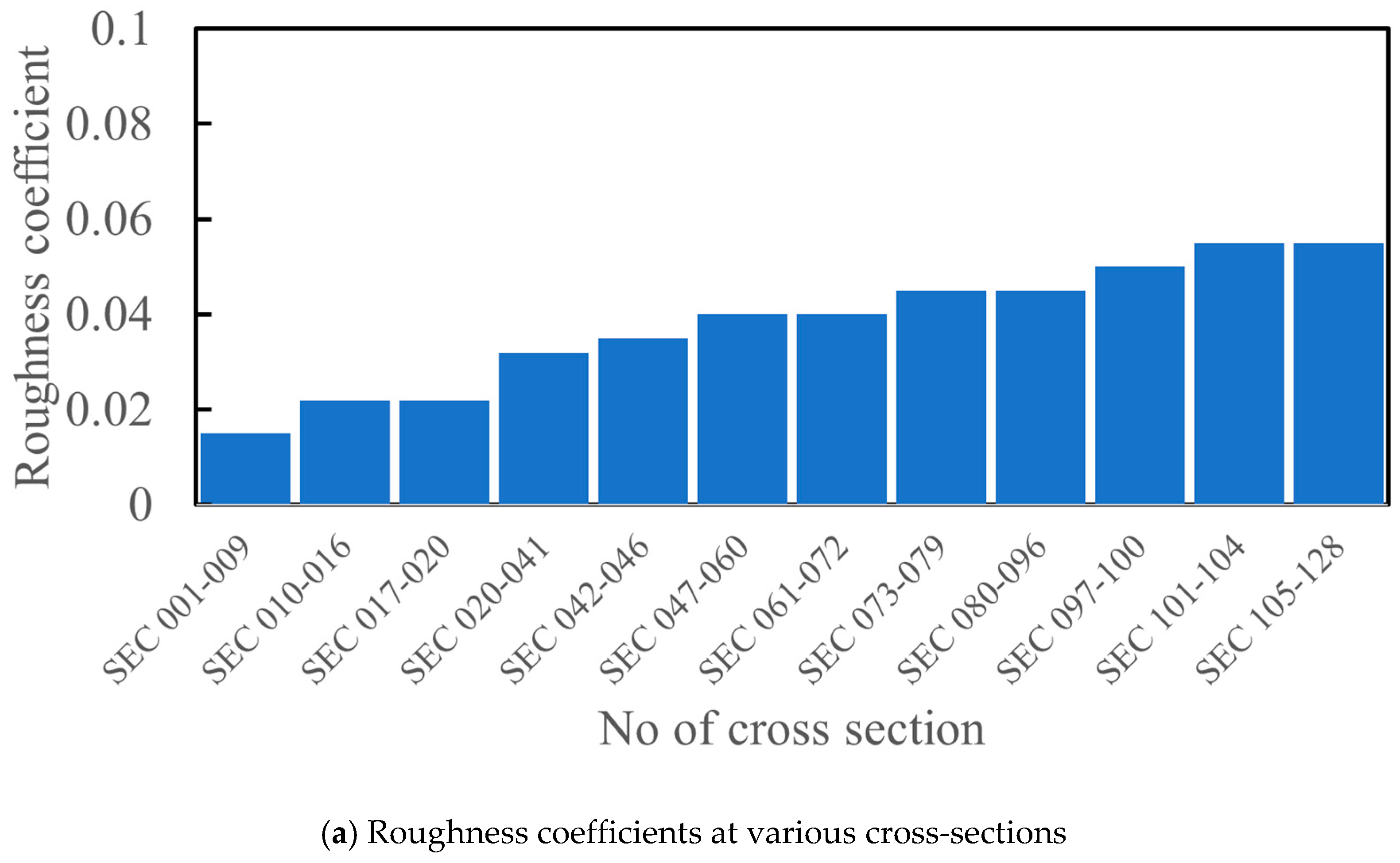

| Event | SAC-SMA Parameters | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UZTWM | UZFWM | UZK | PCTIM | ADIMP | ZPERC | LZTWM | LZFSM | LZSK | DF_L | DF_P | |

| EV1 | 73.55 | 138.71 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 49.52 | 553.65 | 88.79 | 0.17 | 19.00 | 0.11 |

| EV2 | 151.62 | 136.86 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 40.48 | 225.73 | 172.83 | 0.18 | 9.00 | 0.22 |

| EV3 | 152.32 | 357.82 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 55.32 | 104.02 | 112.70 | 0.14 | 11.00 | 0.18 |

| EV4 | 61.90 | 284.41 | 0.96 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 97.79 | 75.61 | 306.53 | 0.15 | 26.00 | 0.08 |

| EV5 | 128.19 | 252.18 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 19.79 | 79.47 | 297.79 | 0.07 | 7.00 | 0.29 |

| EV6 | 41.48 | 80.45 | 0.64 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 14.27 | 151.70 | 445.03 | 0.15 | 8.00 | 0.25 |

| EV7 | 190.57 | 93.23 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 35.60 | 263.63 | 188.17 | 0.17 | 9.00 | 0.22 |

| EV8 | 248.88 | 99.20 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 35.17 | 1077.26 | 104.38 | 0.18 | 30.00 | 0.07 |

| EV9 | 372.60 | 99.11 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 61.92 | 204.29 | 55.07 | 0.20 | 13.00 | 0.15 |

| EV10 | 263.15 | 226.99 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 33.03 | 154.76 | 375.92 | 0.16 | 8.00 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 168.43 | 176.90 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 44.29 | 289.01 | 214.72 | 0.16 | 14.00 | 0.18 |

| Standard | 103.41 | 96.56 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 23.86 | 309.79 | 133.64 | 0.04 | 8.21 | 0.08 |

| Coefficient of variance | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 1.07 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.43 |

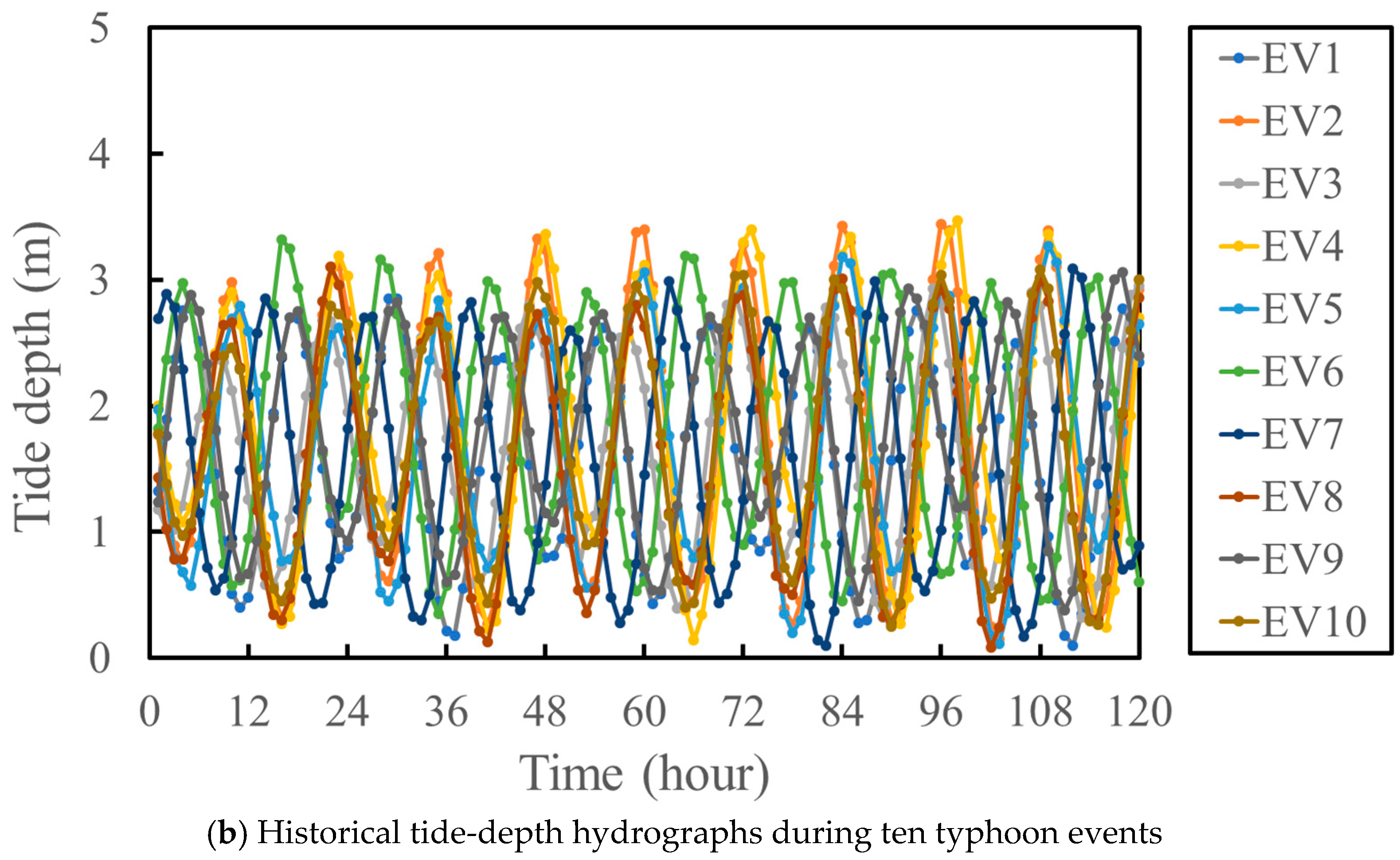

| Control Point | Threshold Number | β0 | β1 | β2 | β3 | β4 | β5 | β6 | β7 | β8 | β9 | β10 | β11 | β12 | β13 | β14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLG1 | First | 45.912 | −0.002 | −0.006 | 0 | −0.013 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 | −0.015 | −0.012 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.006 | −0.005 | −0.001 |

| Second | 35.731 | 0.005 | −0.012 | 0.001 | −0.018 | 0.011 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.028 | −0.029 | 0.011 | 0.038 | 0.019 | −0.005 | −0.006 | |

| WLG2 | First | 43.943 | −0.003 | −0.005 | 0 | −0.012 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | −0.015 | −0.012 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.005 | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| Second | 33.326 | 0.002 | −0.011 | 0.001 | −0.019 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.01 | −0.031 | −0.03 | 0.011 | 0.041 | 0.018 | −0.005 | −0.002 | |

| WLG3 | First | 21.159 | −0.012 | −0.005 | −0.001 | −0.037 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.023 | −0.017 | 0.005 | 0.022 | −0.007 | −0.008 | 0.009 |

| Second | 12.361 | 0.007 | −0.042 | 0.001 | −0.034 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.011 | −0.088 | −0.058 | 0.032 | 0.094 | −0.035 | −0.057 | 0.106 | |

| WLG4 | First | 18.65 | 0.001 | −0.024 | 0.003 | −0.006 | 0.004 | −0.005 | 0.005 | −0.022 | −0.014 | 0 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.004 |

| Second | 11.204 | 0.053 | −0.091 | 0 | −0.09 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.023 | −0.078 | −0.062 | 0.042 | 0.094 | −0.01 | −0.053 | 0.048 | |

| WLG5 | First | 18.104 | 0.009 | −0.03 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.003 | −0.004 | 0.011 | −0.003 | −0.013 | −0.007 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.008 | −0.013 |

| Second | 10.424 | 0.064 | −0.118 | 0 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.023 | −0.054 | −0.056 | −0.002 | 0.07 | 0.032 | 0.001 | −0.012 | |

| WLG6 | First | 13.251 | 0.01 | −0.043 | 0.004 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | 0.008 | 0 | −0.015 | −0.012 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.023 | −0.012 |

| Second | 7.788 | 0.087 | −0.179 | −0.001 | −0.084 | −0.037 | 0.011 | 0.02 | −0.031 | −0.038 | −0.032 | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.047 | −0.051 | |

| WLG7 | First | 11.715 | 0.014 | −0.047 | 0.007 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.001 | 0.006 | −0.01 | −0.017 | −0.009 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.021 | −0.005 |

| Second | 7.518 | 0.112 | −0.211 | −0.003 | −0.078 | −0.028 | 0.017 | 0.025 | −0.038 | −0.049 | −0.024 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.036 | −0.044 | |

| WLG8 | First | 12.661 | 0.01 | −0.046 | 0.004 | 0.008 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.007 | −0.007 | −0.016 | −0.007 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.014 | −0.014 |

| Second | 7.61 | 0.106 | −0.22 | −0.001 | −0.021 | −0.038 | 0.017 | 0.022 | −0.053 | −0.051 | −0.021 | 0.061 | 0.058 | 0.038 | −0.038 | |

| WLG9 | First | 11.973 | −0.005 | −0.03 | 0.002 | 0.009 | −0.007 | −0.007 | 0.007 | −0.01 | −0.014 | −0.002 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.01 | −0.012 |

| Second | 6.549 | 0.068 | −0.139 | 0 | −0.023 | −0.026 | −0.004 | 0.027 | −0.04 | −0.048 | −0.025 | 0.055 | 0.064 | 0.049 | −0.068 | |

| WLG10 | First | 11.588 | −0.011 | −0.011 | 0.002 | 0.028 | −0.055 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.019 | −0.008 | 0.012 | 0.012 | −0.009 | −0.011 | 0.017 |

| Second | 10.863 | 0.008 | −0.072 | 0 | 0.031 | −0.095 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.04 | −0.044 | 0.047 | 0.067 | −0.023 | −0.055 | 0.046 | |

| WLG11 | First | 13.189 | −0.004 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.038 | −0.068 | −0.028 | −0.003 | −0.002 | 0 | 0.006 | 0.003 | −0.006 | −0.012 | 0.012 |

| Second | 19.959 | 0 | −0.03 | −0.001 | 0.087 | −0.116 | −0.01 | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.012 | 0.044 | 0.029 | −0.04 | −0.062 | 0.037 | |

| WLG12 | First | 10.712 | −0.014 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.034 | −0.066 | −0.024 | −0.004 | −0.013 | −0.002 | 0.009 | 0.005 | −0.006 | −0.005 | 0.02 |

| Second | 15.108 | −0.02 | −0.031 | 0 | 0.076 | −0.106 | −0.017 | −0.008 | −0.018 | −0.015 | 0.051 | 0.032 | −0.044 | −0.055 | 0.053 | |

| Mean | First | 19.405 | −0.001 | −0.022 | 0.002 | 0.004 | −0.016 | −0.005 | 0.004 | −0.012 | −0.012 | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Second | 14.870 | 0.041 | −0.096 | 0.000 | −0.017 | −0.034 | 0.004 | 0.014 | −0.041 | −0.041 | 0.011 | 0.057 | 0.013 | −0.010 | 0.006 | |

| Stdev | First | 12.370 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| Second | 9.925 | 0.046 | 0.076 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.047 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.052 |

| Control Point | Threshold Number | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLG1 | First | 125.483 | 0.022 | −0.026 | −19.800 | 0.001 | −2.313 |

| Second | 51.523 | 0.065 | −0.007 | −10.800 | −0.051 | −0.968 | |

| WLG2 | First | 117.074 | −0.074 | −0.022 | −17.900 | 0.009 | −2.235 |

| Second | 50.015 | −0.040 | −0.011 | −31.630 | 0.104 | −0.946 | |

| WLG3 | First | 50.800 | −0.105 | −0.014 | −31.500 | −0.037 | −1.805 |

| Second | 28.503 | −0.028 | −0.042 | 2.700 | 0.029 | −1.090 | |

| WLG4 | First | 39.868 | 0.093 | −0.024 | 5.400 | 0.032 | −1.818 |

| Second | 30.302 | 0.066 | −0.058 | −71.600 | 0.087 | −1.228 | |

| WLG5 | First | 96.818 | 0.061 | −0.062 | 6.200 | 0.064 | −5.145 |

| Second | 31.678 | 0.133 | −0.069 | −19.500 | −0.069 | −1.771 | |

| WLG6 | First | 40.464 | 0.017 | −0.025 | 6.400 | 0.035 | −2.579 |

| Second | 32.813 | 0.251 | −0.120 | −35.100 | −0.256 | −2.212 | |

| WLG7 | First | 42.445 | 0.025 | −0.040 | 5.500 | 0.098 | −2.967 |

| Second | 25.119 | 0.178 | −0.119 | −20.300 | −0.131 | −1.761 | |

| WLG8 | First | 62.669 | 0.011 | −0.067 | 13.400 | −0.001 | −4.715 |

| Second | 24.533 | 0.021 | −0.115 | −18.000 | −0.150 | −1.906 | |

| WLG9 | First | 82.945 | −0.072 | −0.081 | 44.600 | −0.077 | −6.680 |

| Second | 33.176 | 0.170 | −0.094 | −19.800 | −0.089 | −2.819 | |

| WLG10 | First | 98.547 | −0.089 | −0.022 | 75.600 | −1.058 | −9.453 |

| Second | 33.242 | −0.025 | −0.057 | 44.657 | −0.511 | −3.449 | |

| WLG11 | First | 113.398 | −0.060 | −0.016 | 119.100 | −1.886 | −11.414 |

| Second | 35.613 | −0.031 | −0.014 | 90.500 | −4.712 | −2.794 | |

| WLG12 | First | 104.536 | −0.208 | −0.016 | 37.000 | −1.601 | −10.826 |

| Second | 45.712 | −0.059 | −0.023 | 89.400 | −0.938 | −5.355 |

| Control Point | Typhoon in 2016 | Average Rainfall Intensity (mm/h) | Maximum Rainfall Intensity (mm/h) | Roughness Coefficient | Maximum Tide Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGL2 | Megi | 2 | 35.5 | 0.05 | 1.7 |

| Area | 1.5 | 7.5 | 0.05 | 1.4 | |

| WGL5 | Megi | 2.7 | 35 | 0.04 | 1.7 |

| Area | 1 | 10 | 0.04 | 1.4 | |

| WGL10 | Megi | 2.7 | 35 | 0.035 | 1.7 |

| Area | 1 | 10 | 0.035 | 2.9 |

| Control Point | Average Rainfall Intensity (mm/h) | Maximum Rainfall Intensity (mm/h) | Roughness Coefficient | Maximum Tide Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGL2 | 5 | 52 | 0.035 | 1 |

| 0.035 | 2 | |||

| 0.035 | 3 | |||

| WGL5 | 5 | 52 | 0.04 | 1 |

| 0.04 | 2 | |||

| 0.04 | 3 | |||

| WGL10 | 5 | 62 | 0.035 | 1 |

| 0.035 | 2 | |||

| 0.035 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, S.-J.; Yang, H.-W.; Yang, S.-H.; Yeh, K.-C. Modeling Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds for Flood Early Warning. Hydrology 2026, 13, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010030

Wu S-J, Yang H-W, Yang S-H, Yeh K-C. Modeling Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds for Flood Early Warning. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Shiang-Jen, Hao-Wen Yang, Sheng-Hsueh Yang, and Keh-Chia Yeh. 2026. "Modeling Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds for Flood Early Warning" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010030

APA StyleWu, S.-J., Yang, H.-W., Yang, S.-H., & Yeh, K.-C. (2026). Modeling Reliability Quantification of Water-Level Thresholds for Flood Early Warning. Hydrology, 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010030