Abandonment Integrity Assessment Regarding Legacy Oil and Gas Wells and the Effects of Associated Stray Gas Leakage on the Adjacent Shallow Aquifer in the Karoo Basin, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Description of the Study Area

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Geological Setting

2.3. Hydrological Conditions

3. Advocacy for Well Integrity Based on Modern Industry Practices and Regulations

4. Data Collection and Analytical Procedures

4.1. Well Schematic Reconstruction

Data Collection

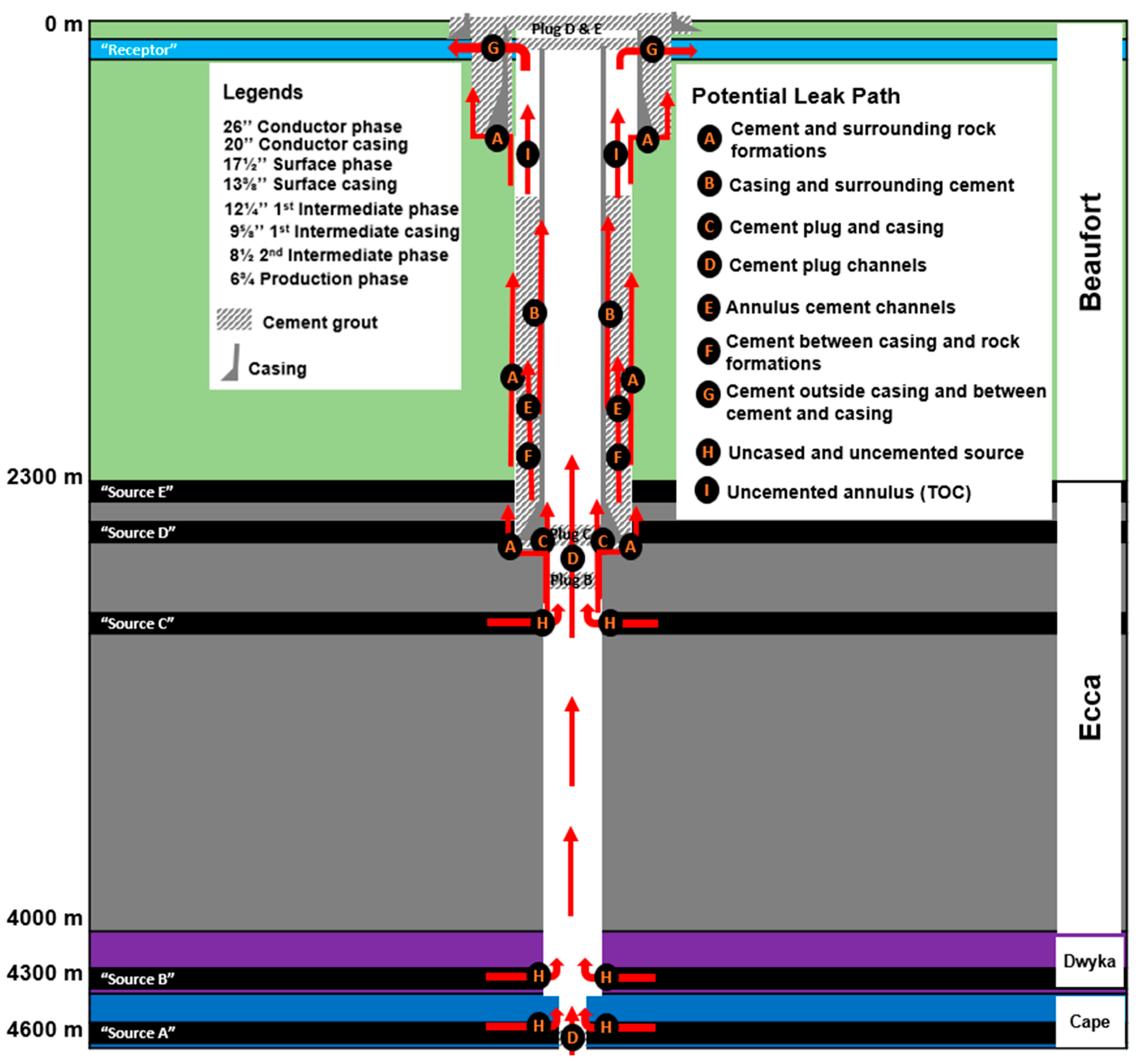

- (A)

- Cement and surrounding rock formations—poor cement and rock formation bonding due to loss of cement slurry in the surrounding rock fractures. According to [39,40] and [64] cement placement must be verified by leak of test (LOT) or cement bond log (CBL). These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (B)

- Casing and surrounding cement—poor cement and casing bonding due to loss of cement slurry in the surrounding rock fractures. According to [39,40] and [64] cement placement must be verified by leak of test (LOT) or cement bond log (CBL). These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (C)

- Cement plug and casing—poor bonding between the cement plug and the casing. According to [39,40] and [64], the placement of cement plug must be verified either by tagging or by conducting a weight test on a drill pipe or by using a wireline with coiled tubing. These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (D)

- Cement plug channels—cement channels on cement plug. According to [39,40] and [64], the placement of cement plug must be verified either by tagging or by conducting a weight test on a drill pipe or by using a wireline with coiled tubing. These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (E)

- Annulus cement channels—channel on annulus cement due to loss of cement slurry in the surrounding rock fractures. According to [39,40] and [64] cement placement must be verified by leak of test (LOT) or cement bond log (CBL). These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (F)

- Fractures in cement between casing and rock formations—fractures that develop overtime between formation–cement–casing. According to [39,40] and [64] cement placement must be verified by leak of test (LOT) or cement bond log (CBL). These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (G)

- Casing corrosion—corrosion that occurs on casing overtime. according to [39,40] and [64], free pipe has high chances to corrode and crack, which allows seepage into the wellbore and successive layers. Casing pipes must be cemented in place to prevent potential corrosion and leakage. Some casings were not cemented whereas others were not fully cemented on risky zones such as hydrocarbon bearing layers. According to these standard frameworks, such zones have high chances of leaking H2S and CO2 which have potential to corrode the pipe.

- (H)

- Un-cased and uncemented sources—hydrocarbon source rock not cased and open to the wellbore. According to [39,40] and [64], zones with potential to leak hydrocarbons must be cased and cemented to prevent leakage. These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Hydrocarbons sources not cased and cement have high chances of leaking into successive layers or wellbore.

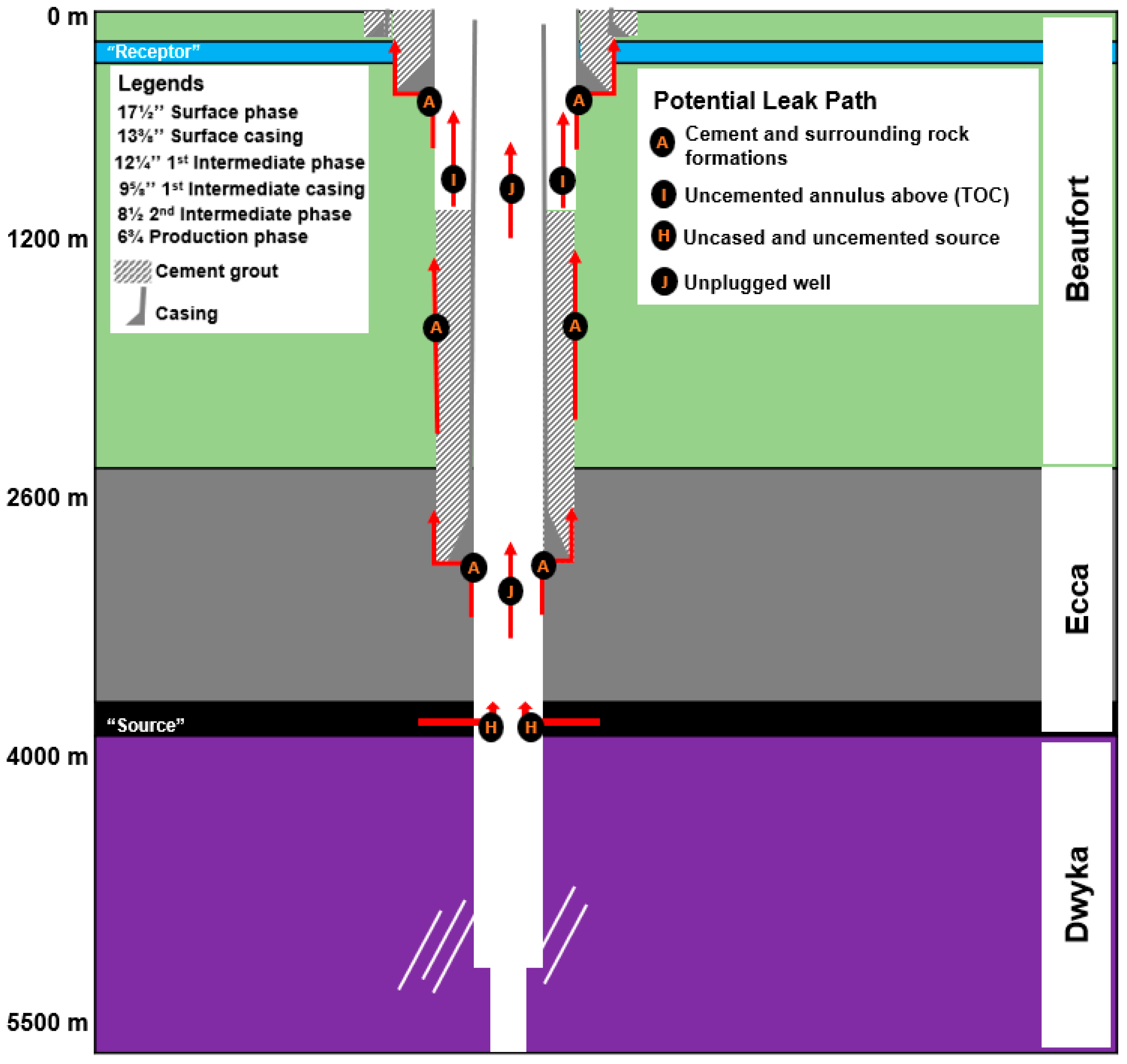

- (I)

- Uncemented section above the top of the cement—annulus sections not fully cement for shallow pressurized zones. According to [39,40] and [64] cement placement must be verified by leak of test (LOT) or cement bond log (CBL). These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

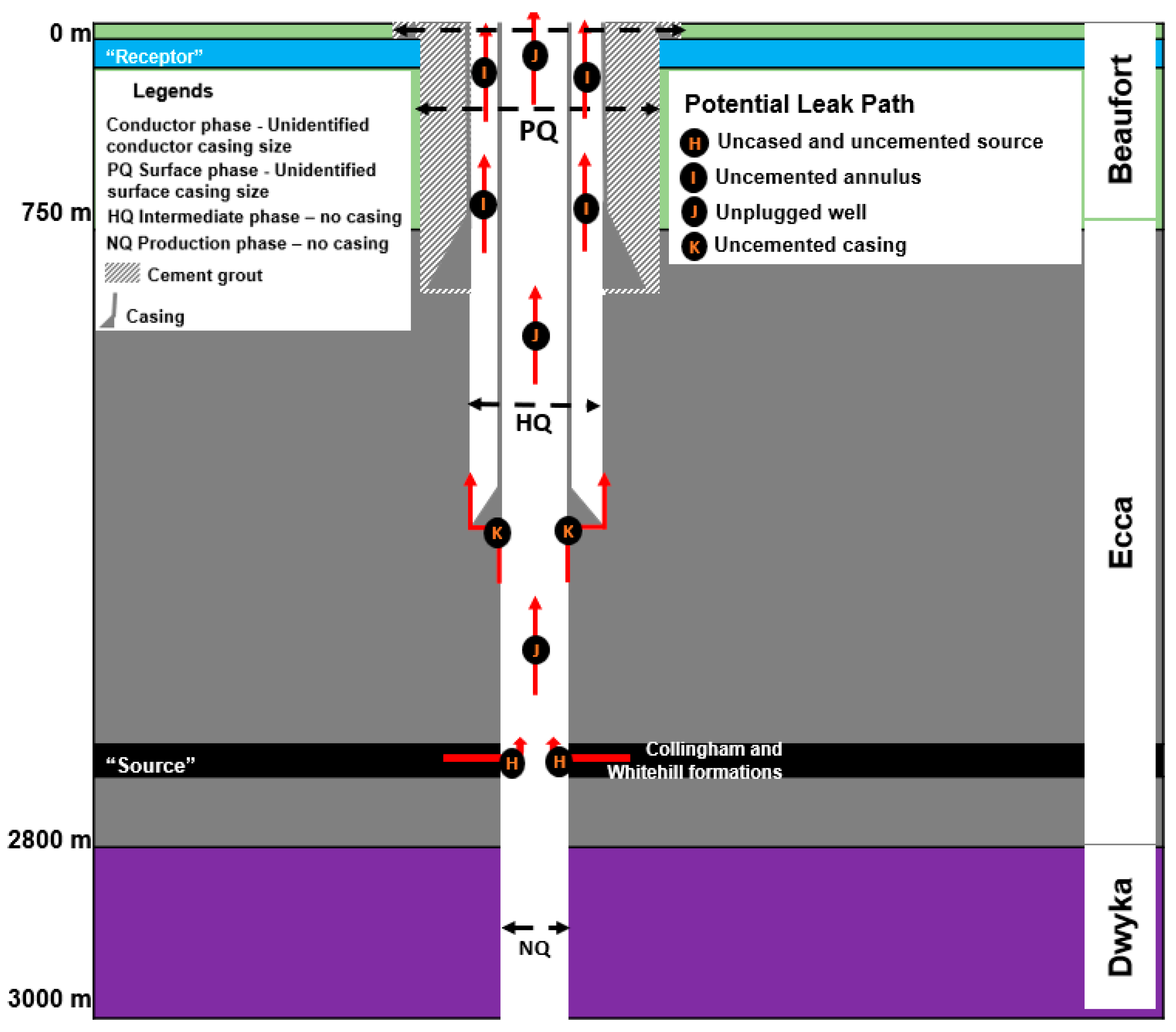

- (J)

- Unplugged well—well abandoned without plugs. According to [39,40] and [64], when wells reach end of life, they must be abandoned with cement plugs to prevent well leakage into the successive layers. The cement plugs placed must be verified either by tagging or by conducting a weight test on a drill pipe or by using a wireline with coiled tubing. These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard framework. Wells not verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

- (K)

- Uncemented casing—annulus sections not cemented at all. According to [39,40] and [64], after casing installation, the casings must be cemented in place to achieve zonal isolation and ensure integrity. Good isolation requires complete annular filling and tight cement interfaces with respect to the formations and casing. After cementing phase, the hole must be pressure-tested using a LOT and CBL to ensure there is no potential leakage. These procedures were not performed on these wells which indicate non-compliance with [39,40] and [64] standard frameworks. Wells not cemented and verified according to these standards have high chances of leaking.

4.2. Geochemical Sampling and Analyses

4.2.1. Field Sampling

4.2.2. Laboratory Analyses

4.3. Data Limitations

5. Results and Interpretation

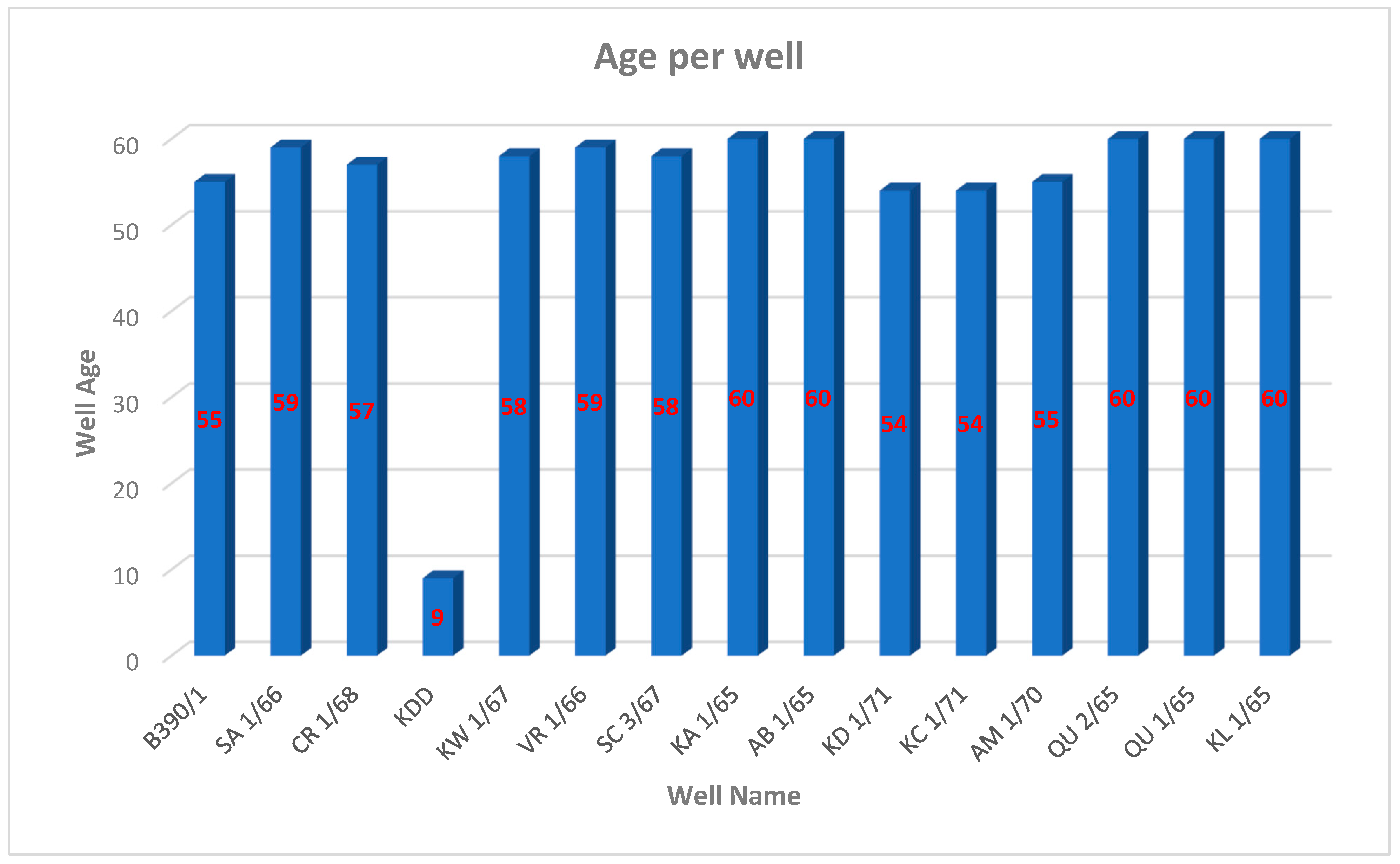

5.1. Assessing Well Schematic Diagrams and Integrity

5.1.1. Well Construction, Plugging, and Abandonment

5.1.2. Assessment of Potential Leakage and Migration

5.1.3. Extrapolation to Wells Without Completion Reports

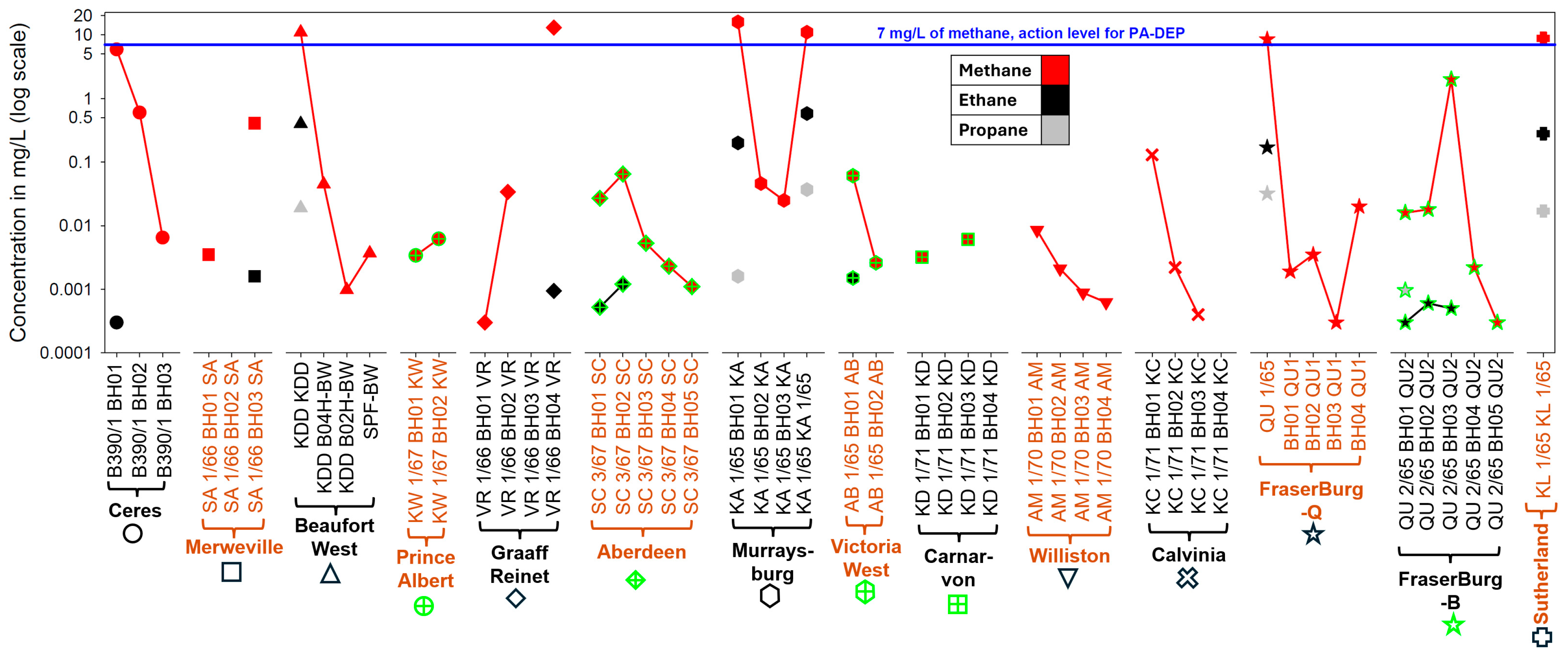

5.2. Geochemical Tracing of Stray Gas Leakage

5.2.1. Dissolved Concentrations of Methane, Ethane, and Propane

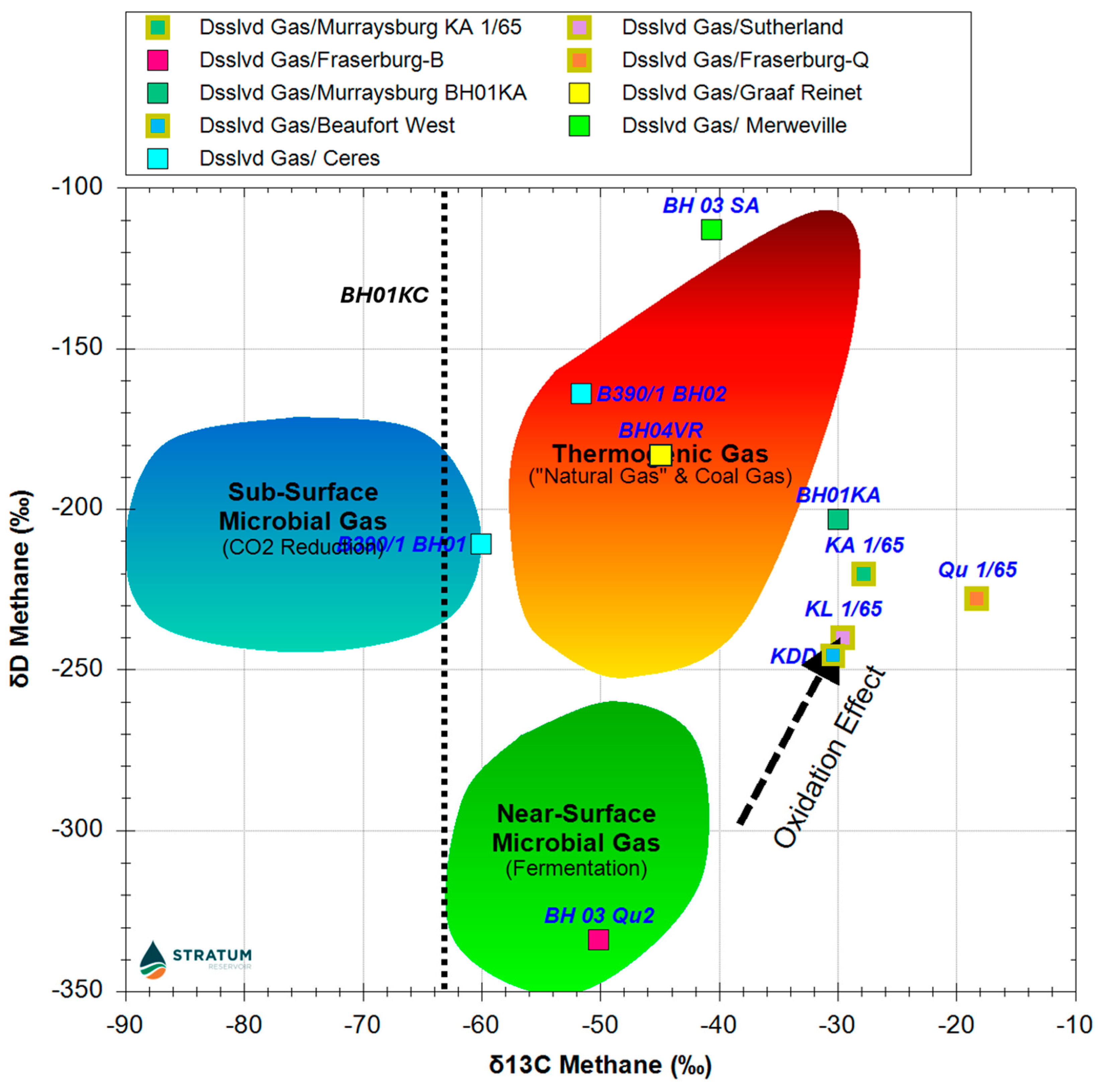

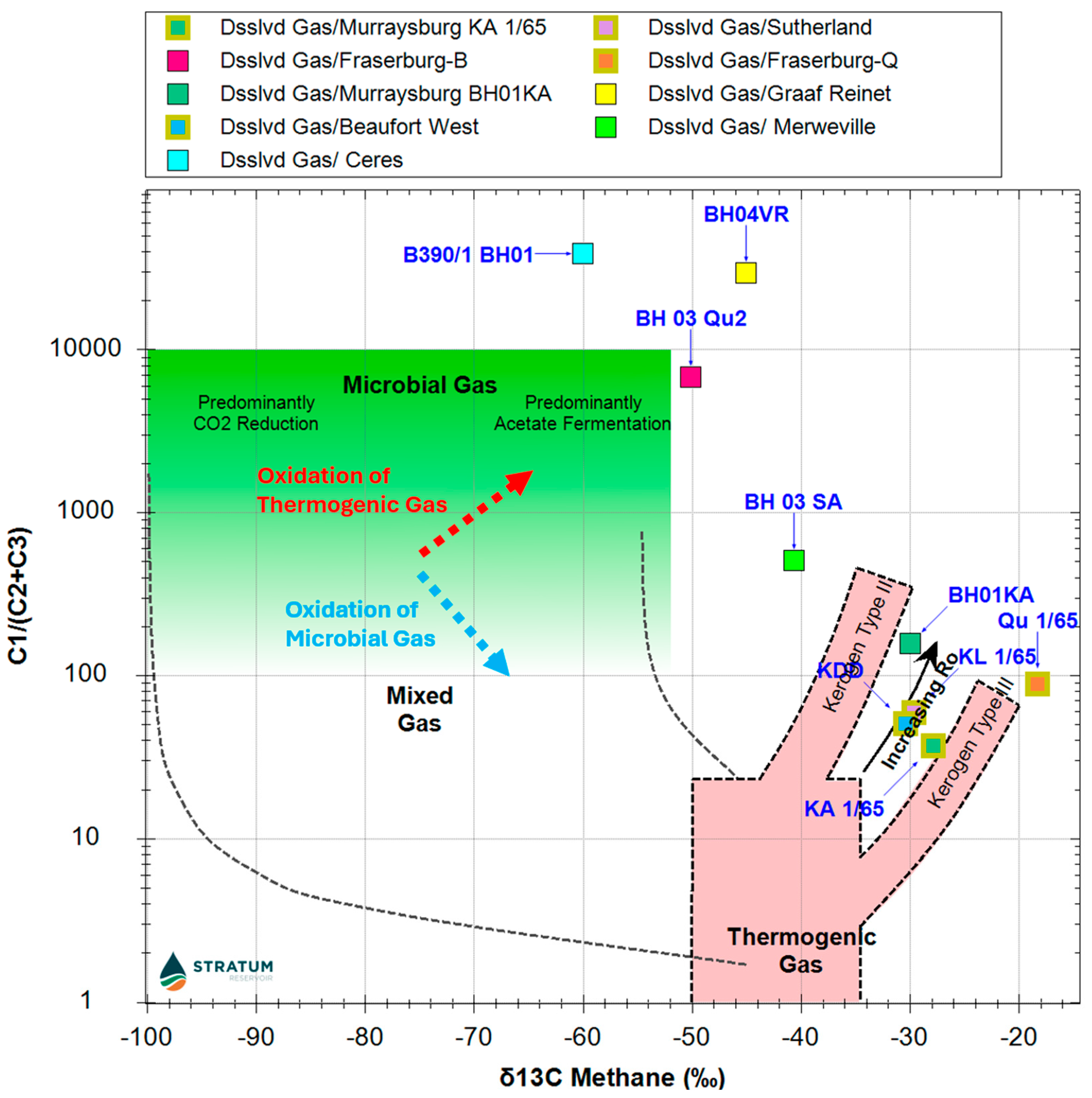

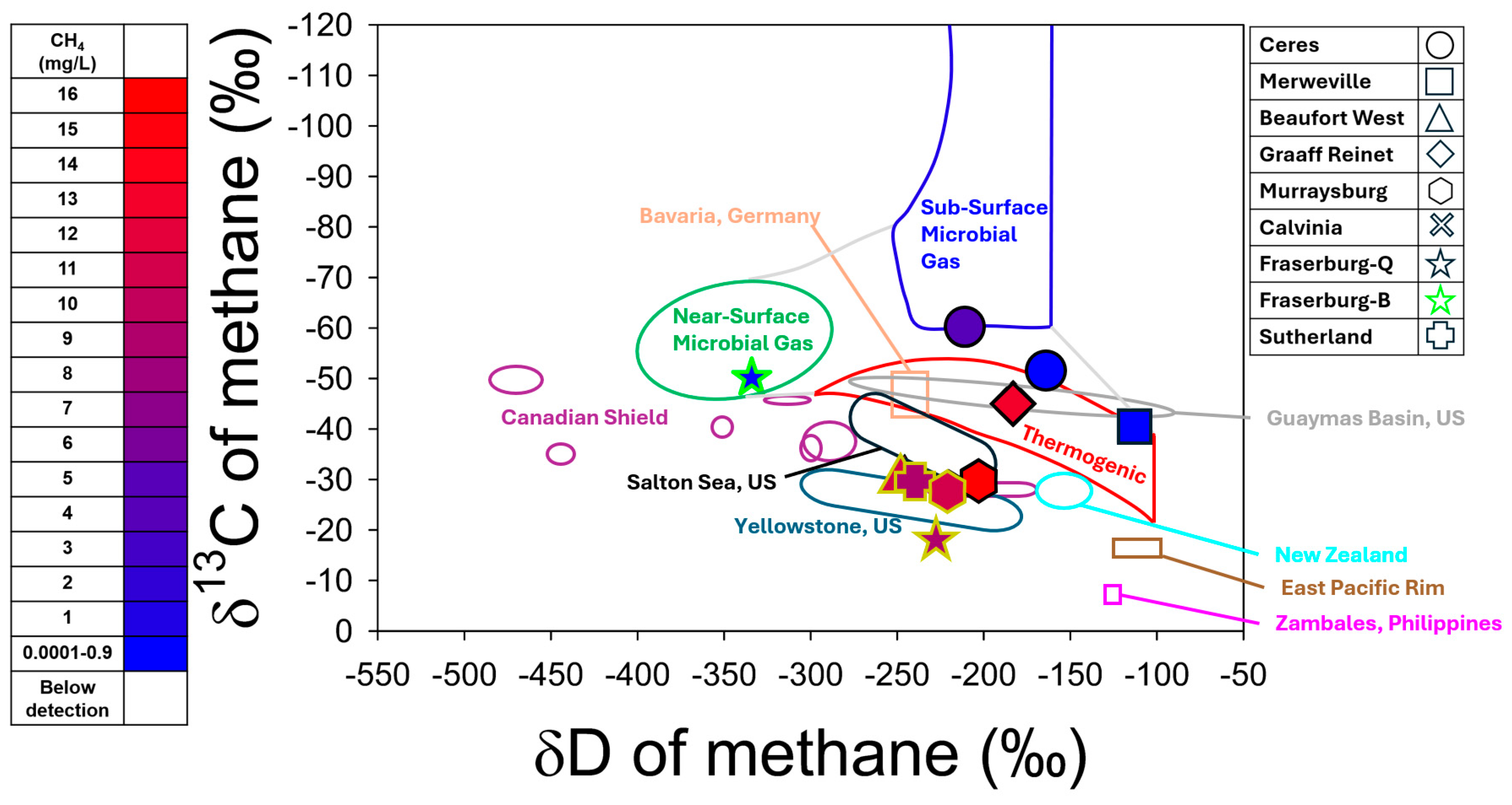

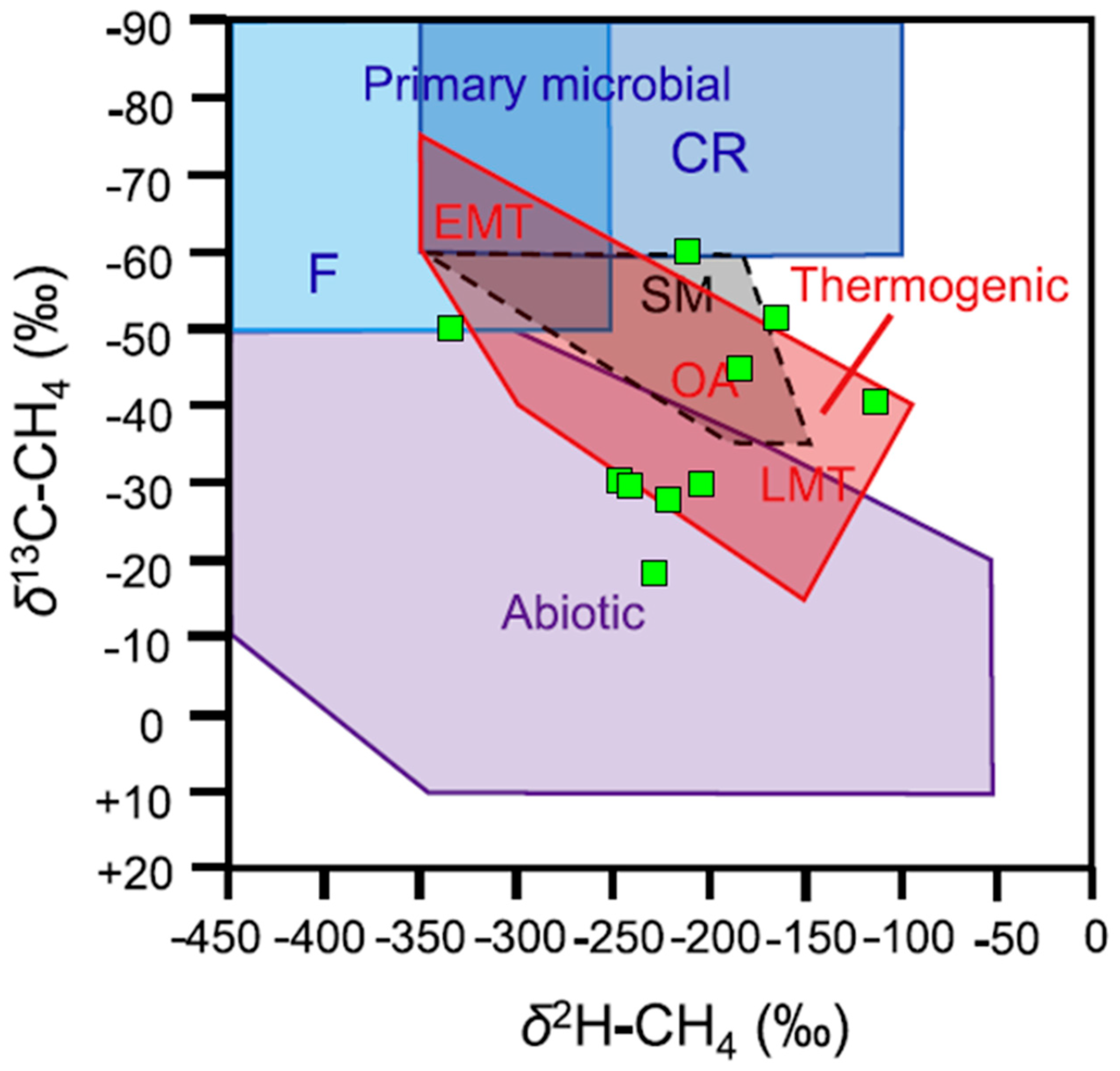

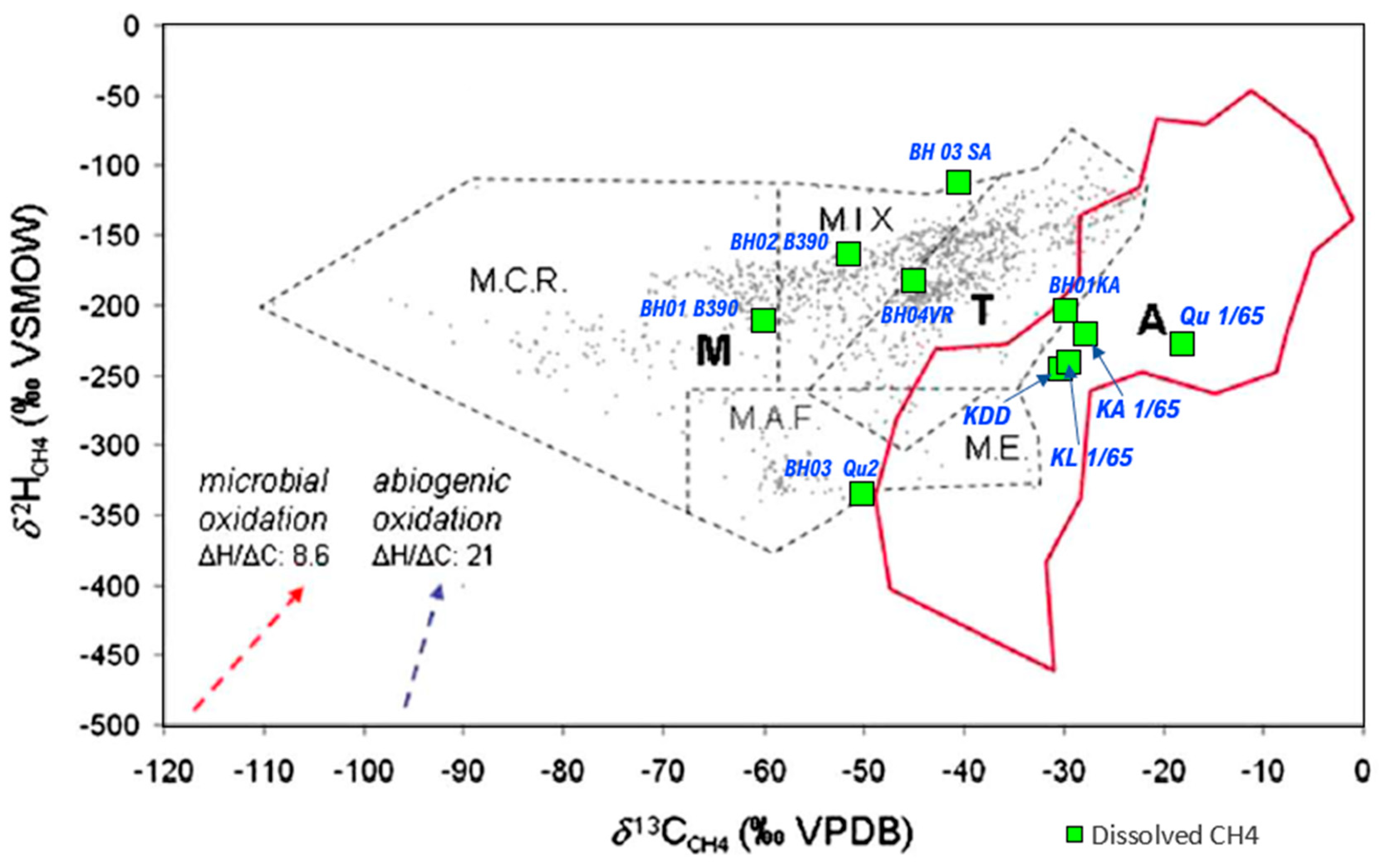

5.2.2. Dissolved Gas δ13C and δD Isotopic Analysis

Interpretation and Analysis

5.3. Integration of Well Barrier Failure and Geochemical Tracing

6. Discussions

6.1. Observations of Abandonment Integrity Assessment and Their Consequences

6.2. Dissolved Gas (δ13C and δD) Isotopic Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAF). South Africa’s Technical Readiness to Support the Shale Gas Industry; Academy of Science South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016; ISBN 978-0-9946852-7-8. Available online: https://research.assaf.org.za (accessed on 12 October 2016).

- Cooper, J.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Shale Gas: A Review of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability. Energy Technol. 2016, 4, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, S.G.; Vengosh, A.; Warner, N.R.; Jackson, R.B. Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Environ. Sci. 2011, 108, 8172–8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.T.; Mugivhi, M.; Hackley, K.C. Baseline assessment of groundwater quality in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. In Proceedings of the 2024 Goldschmidt Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 18–23 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, T.A.; Fleming, N.A.; Attalage, D.; Mayer, B.; Mayer, K.U.; Ryan, M.C. Field investigation of the transport and attenuation of fugitive methane in shallow groundwater around an oil and gas well with gas migration. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 908, 168246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, D.C.; Visser, A.; Bridge, C. Noble Gas Analyses to Distinguish Between Surface and Subsurface Brine Releases at a Legacy Oil Site. Groundwater 2024, 62, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.W.; Wen, T.; Herman, A.; Brantley, S.L. Geochemical Evidence of Potential Groundwater Contamination with Human Health Risks where Hydraulic Fracturing Overlaps with Extensive Legacy Hydrocarbon Extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10010–10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, C.J.; Vengosh, A.; Warner, N.R.; Jackson, R.B.; Muehlenbachs, K.; Schwartz, F.W.; Darrah, T.H. Geochemical evidence for fugitive gas contamination and associated water quality changes in drinking-water wells from Parker County, Texas. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 780, 146555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schout, G.; Griffioen, J.; Hassanizadeh, S.M.; de Lichtbuer, G.C.; Hartog, N. Occurrence and fate of methane leakage from cut and buried abandoned gas wells in the Netherlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, A.; Bishop, A.; Alsop, E.B.; Hull, K.; Rhodes, I.; Hendricks, R.; Head, I.M.; Tsesmetzis, N. Microbial and isotopic evidence for methane cycling in hydrocarbon-containing groundwater from the Pennsylvania region. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montcoudiol, N.; Isherwood, C.; Gunning, A.; Kelly, T.; Younger, P.L. Shale gas impacts on groundwater resources: Understanding the behavior of a shallow aquifer around a fracking site in Poland. Energy Procedia 2017, 125, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, S.T.M.; Szynkiewicz, A.; Faiia, A.M.; Mayes, M.A.; McKinney, M.L.; Dean, W.G. Chemical and isotope compositions of shallow groundwater in areas impacted by hydraulic fracturing and surface mining in the Central Appalachian Basin, Eastern United States. Appl. Geochem. 2016, 71, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, H.L.; Thoma, E.D.; Squier, W.C.; Guven, B.B.; Lyon, D. Assessment of methane emissions from oil and gas production pads using mobile measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14508–14515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassare, F.J.; McCaffrey, M.A.; Harper, J.A. A geochemical context for stray gas investigations in the northern Appalachian Basin: Implications of analyses of natural gases from Neogene-through Devonian-age strata. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2014, 98, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molofsky, L.J.; Connor, J.A.; Van De Ven, C.J.; Hemingway, M.P.; Richardson, S.D.; Strasert, B.A.; McGuire, T.M.; Paquette, S.M. A review of physical, chemical, and hydrogeologic characteristics of stray gas migration: Implications for investigation and remediation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 779, 146234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.E.; Gorody, A.W.; Mayer, B.; Roy, J.W.; Ryan, M.C.; Van Stempvoort, D.R. Groundwater protection and unconventional gas extraction: The critical need for field-based hydrogeological research. Groundwater 2013, 51, 488–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohne, D.; de Lange, F.; Esterhuyse, S.; Lollar, B.S. Case study: Methane gas in a groundwater system located in a dolerite ring structure in the Karoo Basin; South Africa. South Afr. J. Geol. 2019, 122, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebel, D.H.; Thiart, C.; De Wit, M. Towards defining a baseline status of scarce groundwater resources in anticipation of hydraulic fracturing in the eastern cape karoo, South Africa: Salinity, aquifer yields and groundwater levels. In Geological Society Special Publication; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2019; Volume 479, pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.S.; Swana, K.; Eymold, W.K.; Miller, J.; Murray, R.; Talma, S.; Whyte, C.J.; Moore, M.T.; Maletic, E.L.; Vengosh, A.; et al. Pre-drill Groundwater Geochemistry in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Groundwater 2018, 56, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eymold, W.K.; Swana, K.; Moore, M.T.; Whyte, C.J.; Harkness, J.S.; Talma, S.; Murray, R.; Moortgat, J.B.; Miller, J.; Vengosh, A.; et al. Hydrocarbon-Rich Groundwater above Shale-Gas Formations: A Karoo Basin Case Study. Groundwater 2018, 56, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Swana, K.; Talma, S.; Vengosh, A.; Tredoux, G.; Murray, R.; Butler, M. O, H, CDIC, Sr, B and 14C Isotope Fingerprinting of Deep Groundwaters in the Karoo Basin, South Africa as a Precursor to Shale Gas Exploration. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 13, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talma, A.S.; Esterhuyse, C. Isotopic clues to the origin of methane emissions in the Karoo. South Afr. J. Geol. 2015, 118, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, R.; Teodoriu, C.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Nygaard, R.; Wood, D.; Mokhtari, M.; Salehi, S. Identification and evaluation of well integrity and causes of failure of well integrity barriers (A review). J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 45, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Brandt, A.R.; Zheng, Z.; Boutot, J.; Yung, C.; Peltz, A.S.; Jackson, R.B. Orphaned oil and gas well stimulus-maximizing economic and environmental benefits. Elementa 2021, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianoutsos, N.J.; Haase, K.B.; Birdwell, J.E. Geologic sources and well integrity impact methane emissions from orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 912, 169584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, P.B.; Thomas, J.C.; Crawford, J.T.; Dornblaser, M.M.; Hunt, A.G. Methane in groundwater from a leaking gas well, Piceance Basin, Colorado, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.J.; Almond, S.; Ward, R.S.; Jackson, R.B.; Adams, C.; Worrall, F.; Herringshaw, L.G.; Gluyas, J.G.; Whitehead, M.A. Oil and gas wells and their integrity: Implications for shale and unconventional resource exploitation. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2014, 56, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Boutot, J.; McVay, R.C.; A Roberts, K.; Jasechko, S.; Perrone, D.; Wen, T.; Lackey, G.; Raimi, D.; Digiulio, D.C.; et al. Environmental risks and opportunities of orphaned oil and gas wells in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 074012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.D. Gas Well Integrity and Associated Gas Migration Investigations in the Marcellus Shale. J. Natl. Acad. Forensic Eng. 2016, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Xun, Y.; Liu, H.; Qi, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. An investigation of hydraulic fracturing initiation and location of hydraulic fracture in preforated oil shale formations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, M.A.; Kornacki, A.S.; Laughrey, C.D.; Patterson, B.A. Stray gas source determination using forensic geochemical data. Interpretation 2023, 11, SC11–SC26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Turhan, C.; Wang, N.; Wu, C.; Ashok, P.; Van Oort, E. Prioritizing Wells for Repurposing or Permanent Abandonment Based on Generalized Well Integrity Risk Analysis. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5001633 (accessed on 16 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Doble, R.; Mallants, D.; Huddlestone-Holmes, C.; Peeters, L.J.; Kear, J.; Turnadge, C.; Wu, B.; Noorduijn, S.; Arjomand, E. A multi-stage screening approach to evaluate risks from inter-aquifer leakage associated with gas well and water bore integrity failure. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, K.; Kang, M. Reducing oil and gas well leakage: A review of leakage drivers, methane detection and repair options. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2023, 3, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraffe, A.R.; Wells, M.T.; Santoro, R.L.; Shonkoff, S.B.C. Assessment and risk analysis of casing and cement impairment in oil and gas wells in Pennsylvania, 2000–2012. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10955–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuzer, R.L.; Darrah, T.H.; Grove, B.S.; Moore, M.T.; Warner, N.R.; Eymold, W.K.; Whyte, C.J.; Mitra, G.; Jackson, R.B.; Vengosh, A.; et al. Structural and Hydrogeological Controls on Hydrocarbon and Brine Migration into Drinking Water Aquifers in Southern New York. Groundwater 2018, 56, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.; Darrah, T.H.; Warner, N.R.; Whyte, C.J.; Moore, M.T.; Millot, R.; Kloppmann, W.; Jackson, R.B.; Vengosh, A. The geochemistry of naturally occurring methane and saline groundwater in an area of unconventional shale gas development. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 208, 302–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, M.; Saasen, A. Introduction to Permanent Plug and Abandonment of Wells; Ocean Engineering & Oceanography, Vol. 12; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oil and Gas UK. Guidelines for Suspension and Abandonment of Wells; Oil and Gas UK: Aberdeen, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NORSOK Standard D.-010; Well Integrity in Drilling and Well Operations. Standard Norge: Oslo, Norway, 2013. Available online: www.standard.no/petroleum (accessed on 12 October 2016).

- Gulliford, A.R.; Flint, S.S.; Hodgson, D.M. Crevasse splay processes and deposits in an ancient distributive fluvial system: The lower Beaufort Group, South Africa. Sediment. Geol. 2017, 358, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankard, A.; Welsink, H.; Aukes, P.; Newton, R.; Stettler, E. Tectonic evolution of the Cape and Karoo basins of South Africa. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2009, 26, 1379–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, B.; Durrheim, R.J. An Integrated Geophysical and Geological Interpretation of the Southern African Lithosphere. In Geology of Southwest Gondwana; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 19–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, M.P. Integrated Geochronology and Petrogenesis of Volcanic Suites for Integrated Geochronology and Petrogenesis of Volcanic Suites for Tectonic Sedimentary Studies: Karoo Basin, South Africa. 2015. [Online]. Available online: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd (accessed on 12 October 2016).

- López-Gamundí, O. Permian plate margin volcanism and tuffs in adjacent basins of west Gondwana: Age constraints and common characteristics. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2006, 22, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, A.C.; Chevallier, L. Hydrogeology of the Karoo Basin: Current Knowledge and Future Needs, Pretoria; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, J.N.J.; Van Niekerk, B.N.; Van Der Merwe, S.W. Sediment transport of the Late Palaeozoic glacial Dwyka Group in the southwestern Karoo Basin. South Afr. J. Geol. 1997, 100, 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, H.-M.; Chere, N.; Geel, C.; Booth, P.; de Wit, M.J. Is the Postglacial History of the Baltic Sea an Appropriate Analogue for the Formation of Black Shales in the Lower Ecca Group (Early Permian) of the Karoo Basin, South Africa? In Origin and Evolution of the Cape Mountains and Karoo Basin; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, M.O.; Beukes, N.J.; Adeniyi, E.O.; Cole, D.; Götz, A.E.; Geel, C.; Ossa, F.-G. Deflating the shale gas potential of South Africa’s Main Karoo basin. South Afr. J. Sci. 2017, 113, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, K.; Tsikos, H.; Horsfield, B.; Schulz, H.M.; Harris, N.B.; Frazenburg, M. The effects of Jurassic igneous intrusions on the generation and retention of gas shale in the Lower Permian source-reservoir shales of Karoo Basin, South Africa. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 269, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, S.; Geel, C.; Amann-Hildenbrand, A.; Krooss, B.M.; Littke, R. Petrophysical and geochemical characterization of potential unconventional gas shale reservoirs in the southern Karoo Basin, South Africa. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 212, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nengovhela, V.; Linol, B.; Bezuidenhout, L.; Dhansay, T.; Muedi, T.; de Wit, M.J. Shale gas leakage in lower ecca shales during contact metamorphism by dolerite sill intrusions in the Karoo basin, South Africa. South Afr. J. Geol. 2021, 124, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.R.; Van Vuuren, C.J.; Hegenberger, W.F.; Key, R.; Show, U. Stratigraphy of the Karoo Supergroup in southern Africa: An overview. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1996, 23, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vargas, M.R.; da Silveira, A.S.; Bressane, A.; D’Avila, R.S.F.; Faccion, J.E.; Paim, P.S.G. The Devonian of the Paraná Basin, Brazil: Sequence stratigraphy, paleogeography, and SW Gondwana interregional correlations. Sediment. Geol. 2020, 408, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnes, I.; Svensen, H.; Polteau, S.; Planke, S. Contact metamorphic devolatilization of shales in the Karoo Basin, South Africa, and the effects of multiple sill intrusions. Chem. Geol. 2011, 281, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithard, T.; Bordy, E.M.; Reid, D. The effect of dolerite intrusions on the hydrocarbon potential of the Lower Permian Whitehill Formation (Karoo Supergroup) in South Africa and southern Namibia: A preliminary study. South Afr. J. Geol. 2015, 118, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F.; Panichi, C.; Gonfiantini, R.; Magro, G.; Scandiffio, G. Isotope systematics of C-bearing gas compounds in the geothermal fluids of Larderello, Italy. Geothermics 2005, 34, 442–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldbusch, E.; Wiersberg, T.; Zimmer, M.; Regenspurg, S. Origin of gases from the geothermal reservoir Groß Schönebeck (North German Basin). Geothermics 2018, 71, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughrey, C.D. Produced Gas and Condensate Geochemistry of the Marcellus Formation in the Appalachian Basin: Insights into Petroleum Maturity, Migration, and Alteration in an Unconventional Shale Reservoir. Minerals 2022, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, F.; Allwright, A.; Esterhuyse, S.; Govender, N.; Makiwane, N. Characterisation and Protection of Potential Deep Aquifers in South Africa; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020; WRC Report 2434/1: 19; Available online: www.wrc.org.za (accessed on 12 October 2016).

- Mahed, G. Development of a conceptual geohydrological model for a fractured rock aquifer in the Karoo, near Sutherland, South Africa. South Afr. J. Geol. 2016, 119, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Titus, R.; Pietersen, K.; Tredoux, G.; Harris, C. Hydrochemical characteristics of aquifers near Sutherland in the Western Karoo, South Africa. J. Hydrol. 2001, 241, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, K.; Buckley, S.J.; Chevallier, L.; Fagereng, Å.; Galland, O.; Kurz, T.H.; Ogata, K.; Planke, S.; Tveranger, J. Fracturing of doleritic intrusions and associated contact zones: Implications for fluid flow in volcanic basins. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2015, 102, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16530-2:2017; N.N. (ISO), Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—Well Integrity Part 2: Well Integrity for the Operational Phase. CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Bruxelles, Brussels, 2017.

- Wu, B.; Doble, R.; Turnadge, C.; Mallants, D. Well failure mechanisms and conceptualisation of reservoir-aquifer failure pathways. In Proceedings of the Society of Petroleum Engineers—SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Perth, Australia, 25–27 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.R.; Khalifeh, M.; Nordam, T.; Saasen, A. The fate of hydrocarbon leaks from plugged and abandoned wells by means of natural seepages. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.D.; Liu, C.-L.; Hackley, K.C.; Pelphrey, S.R. Isotopic Identification of Landfill Methane. 1995. Available online: https://archives.datapages.com/data/deg/1995/002002/95_deg020095.htm (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Taylor, S.W.; Lollar, B.S.; Wassenaar, L.I. Bacteriogenic ethane in near-surface aquifers: Implications for leaking hydrocarbon well bores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 4727–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claypool, G.E.; Kvenvolden, K.A. Methane and other hydrocarbon gases in marine sediment. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1983, 11, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, B.B.; Brooks, J.M.; Sackett, W.M. Natural gas seepage in the Gulf of Mexico. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1976, 31, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.T.; Vinson, D.S.; Whyte, C.J.; Eymold, W.K.; Walsh, T.B.; Darrah, T.H. Differentiating between biogenic and thermogenic sources of natural gas in coalbed methane reservoirs from the Illinois Basin using noble gas and hydrocarbon geochemistry. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2018, 468, 151–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burruss, R.C.; Laughrey, C.D. Carbon and hydrogen isotopic reversals in deep basin gas: Evidence for limits to the stability of hydrocarbons. Org. Geochem. 2010, 41, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.D.; Meents, W.F.; Liu, C.-L.; Keogh, R.A. Isotopic Identification of Leakage Gas from Underground Storage Reservoirs—A Progress Report; Illinois Petroleum Series 111; Illinois State Geological Survey: Champaign, IL, USA, 1977; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Whiticar, M.J. A geochemical perspective of natural gas and atmospheric methane. Org. Geochem. 1990, 16, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.M.; Gormly, J.R.; Squires, R.M. “Origin of gaseous hydrocarbons in subsurface environments” theoretical considerations of carbon isotope distribution. Chem. Geol. 1988, 71, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.D. Identifying Methane Emissions with Isotopic and Hydrochemical Clues to Their Origin Across Selected Areas of the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, South Africa.

- Linol, B.; Chere, N.; Muedi, T.; Nengovhela, V.; de Wit, M.J. Deep Borehole Lithostratigraphy and Basin Structure of the Southern Karoo Basin Re-Visited. In Origin and Evolution of the Cape Mountains and Karoo Basin; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chere, N.; Linol, B.; de Wit, M.; Schulz, H.M. Lateral and temporal variations of black shales across the southern karoo basin—Implications for shale gas exploration. South Afr. J. Geol. 2017, 120, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, B.; Fritz, P.; Frape, S.K.; Macko, S.A.; Weise, S.M.; Welhan, J.A. Methane occurrences in the Canadian Shield. Chem. Geol. 1988, 71, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welhan, J.A. Origins of methane in hydrothermal systems. Chem. Geol. 1988, 71, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, P.; Weise, S.M.; Althaus, E.; Bach, W.; Behr, H.J.; Borchardt, R.; Bräuer, K.; Drescher, J.; Erzinger, J.; Faber, E.; et al. Paleofluids and recent fluids in the upper continental crust: Results from the German Continental Deep Drilling Program (KTB). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1997, 102, 18233–18254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welhan, J.A.; Lupton, J.E. Light Hydrocarbon Gases in Guaymas Basin Hydrothermal Fluids: Thermogenic Versus Abiogenic Origin. AAPG Bull. 1987, 71, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, G.L.; Hulston, J.R. Carbon and hydrogen isotopic compositions of New Zealand geothermal gases. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrajano, T.A.; Sturchio, N.C.; Bohlke, J.K.; Lyon, G.L.; Poreda, R.J.; Stevens, C.M. Methane-hydrogen gas seeps, Zambales Ophiolite, Philippines: Deep or shallow origin? Chem. Geol. 1988, 71, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkov, A.V.; Faiz, M.; Etiope, G. Geochemistry of shale gases from around the world: Composition, origins, isotope reversals and rollovers, and implications for the exploration of shale plays. Org. Geochem. 2020, 143, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazaz, A.M.; Bebout, B.M.; Kelley, C.A.; Poole, J.; Chanton, J.P. Redefining the isotopic boundaries of biogenic methane: Methane from endoevaporites. Icarus 2013, 224, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etiope, G.; Lollar, B.S. Abiotic methane on earth. Rev. Geophys. 2013, 51, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Legacy Wells | Boreholes | Farm | Town | Borehole Depth (mbgl) | Proximity to Deep Well |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B390/1 | BH 01 B390/1 | Blaauwbosch Kalk | Ceres | 100.0 | 0.5 km |

| BH 02 B390/1 | Blaauwbosch Kalk | Ceres | 132.2 | 1.2 km | |

| BH 03 B390/1 | Blaauwbosch Kalk | Ceres | 83.5 | 1.3 km | |

| SA 1/66 | BH 01 SA | Sambokraal | Merweville | 85.0 | 1.0 km |

| BH 02 SA | Sambokraal | Merweville | 50.0 | 2.0 km | |

| BH 03 SA | Sambokraal | Merweville | 73.4 | 3.0 km | |

| KDD | KDD | Commonage Land | Beaufort West | 2978 | 0 |

| B 02 H–BW KDD | Commonage Land | Beaufort West | 169.0 | 0.5 km | |

| B 04 H–BW KDD | Commonage Land | Beaufort West | 169.0 | 1.0 km | |

| SPF-BW KDD | Commonage Land | Beaufort West | 144.5 | 1.5 km | |

| KW 1/67 | BH 01 KW | Klein Waterval | Prince Albert | 24.0 | 0.1 km |

| BH 02 KW | Klein Waterval | Prince Albert | 34.0 | 0.2 km | |

| VR 1/66 | BH 01 VR | Vrede | Graaff-Reinet | 10.0 | 0.4 km |

| BH 02 VR | Vrede | Graaff-Reinet | 12.0 | 0.75 km | |

| BH 03 VR | Vrede | Graaff-Reinet | 12.0 | 1.0 km | |

| BH 04 VR | Vrede | Graaff-Reinet | 23.0 | 3.0 km | |

| SC 3/67 | BH 01 SC | Skietfontein | Aberdeen | 50.0 | 0.75 km |

| BH 02 SC | Skietfontein | Aberdeen | 50.0 | 1.5 km | |

| BH 03 SC | Skietfontein | Aberdeen | 50.0 | 4.0 km | |

| BH 04 SC | Skietfontein | Aberdeen | 50.0 | 1.75 km | |

| BH 05 SC | Skietfontein | Aberdeen | 50.0 | 1.0 km | |

| KA 1/65 | KA 1/65 | Karee Bosch | Murraysburg | 2600.0 | 0 |

| BH 01 KA | Karee Bosch | Murraysburg | 100.0 | 6.5 km | |

| BH 02 KA | Karee Bosch | Murraysburg | 50.0 | 2.0 km | |

| BH 03 KA | Karee Bosch | Murraysburg | 25.0 | 3.0 km | |

| AB 1/65 | BH 01 AB | Abrahamskraal | Victoria West | 65.0 | 1.5 km |

| BH 02 AB | Abrahamskraal | Victoria West | 85.0 | 3.75 km | |

| KD 1/71 | BH 01 KD | Heuwels | Carnarvon | 132.0 | 0.25 km |

| BH 02 KD | Heuwels | Carnarvon | 100.0 | 1.5 km | |

| BH 03 KD | Heuwels | Carnarvon | 78.0 | 4.0 km | |

| BH 04 KD | Heuwels | Carnarvon | 55.0 | 6.0 km | |

| KC 1/71 | BH 01 KC | Kwaggasfontein | Calvinia | 72.0 | 0.75 km |

| BH 02 KC | Kwaggasfontein | Calvinia | 60.0 | 1.0 km | |

| BH 03 KC | Kwaggasfontein | Calvinia | 55.0 | 9.0 km | |

| BH 04 KC | Kwaggasfontein | Calvinia | 45.0 | 10.5 km | |

| AM 1/70 | BH 01 AM | Amersfontein | Williston | 25.0 | 0.6 km |

| BH 02 AM | Amersfontein | Williston | 25.0 | 0.75 km | |

| BH 03 AM | Amersfontein | Williston | 20.0 | 1.8 km | |

| BH 04 AM | Amersfontein | Williston | 22.0 | 1.0 km | |

| CR 1/68 | Not sampled due land access issues | ||||

| QU 2/65 | BH 01 QU2 | Beeswater | Fraserburg | 53.0 | 1.0 km |

| BH 02 QU2 | Beeswater | Fraserburg | 60.9 | 500 m | |

| BH 03 QU2 | Beeswater | Fraserburg | 74.4 | 200 m | |

| BH 04 QU2 | Beeswater | Fraserburg | 95.0 | 16.0 km | |

| BH 05 QU2 | Beeswater | Fraserburg | 25.0 | 8.0 km | |

| QU 1/65 | QU1/65 | Quaggasfontein | Fraserburg | 2490.0 | 0 |

| BH 01 QU1 | Quaggasfontein | Fraserburg | 70.0 | 1.5 km | |

| BH 02 QU1 | Quaggasfontein | Fraserburg | 35.0 | 2.0 km | |

| BH 03 QU1 | Quaggasfontein | Fraserburg | 5.0 | 1.8 km | |

| BH 04 QU1 | Quaggasfontein | Fraserburg | 30.0 | 1.9 km | |

| KL 1/65 | KL 1/65 | Klipdrift | Sutherlands | 3500.0 | 0 |

| Well | TD, Driller | Well Phase | Hole Sizes | Drilled Depth | Casing Size | Cased Depth | Grouting Depth | Plugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA 1/65 | 2600.6 m | Conductor | 26″ | 9.7 m | Open hole | - | - | No plug |

| Surface | 17½″ | 187.4 m | 13⅜″ | 186.8 m | To surface | No plug | ||

| Intermediate | 12¼″ | 2327.7 m | 9⅝″ | 2302.4 m | To 2071.1 m | 792.4 m | ||

| 1865.3 m | ||||||||

| Production | 8½″ | 2600.5 m | Open hole | - | - | No plug | ||

| CR 1/68 | 4657.9 m | Conductor | 26″ | 19.8 m | 20″ | 19.5 m | To surface | No plug |

| Surface | 17½″ | 158.4 m | 13⅜″ | 157.2 m | To surface | No plug | ||

| 1st Intermediate | 12¼ | 2531.6 m | 9⅝″ | 2489.2 m | To 447.1 m | Surface | ||

| 243.8 | ||||||||

| 2nd Intermediate | 8½ | 4388.8 m | Open hole | - | - | 2488.9 | ||

| 2743.2 m | ||||||||

| Production | 6¾ | 4657.9 m | Open hole | - | - | 4593.9 m | ||

| KW 1/67 | 5554.6 m | Conductor | 26″ | 19.8 m | 20″ | 19.5 m | To surface | No plug |

| Surface | 17½″ | 305.7 m | 13⅜″ | 304.7 m | To surface | No plug | ||

| 1st Intermediate | 12¼″ | 3049.5 m | 9⅝″ | 3048.6 m | Not mentioned | No plug | ||

| 2nd Intermediate | 8½″ | 5216 m | Open hole | - | - | No plug | ||

| Production | 6¾″ | 5554 m | Open hole | - | - | No plug | ||

| KDD | 2978.82 m | Conductor | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Surface | PQ | 950 m | Unidentified | 950 m | To surface | No plug | ||

| Intermediate | HQ | 1750 m | Unidentified | 1750 m | - | No plug | ||

| Production | NQ | 2978.82 m | Open hole | - | - | No plug |

| Isotech | Sample | Field | Location | Sampling | δ13C1 | δDC1 | δ13C2 | Dissolved CH4 | Dissolved C2H6 | Dissolved C3H8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab No. | Name | Name | Point | ‰ | ‰ | ‰ | cc/L | mg/L | cc/L | mg/L | cc/L | mg/L | |

| 872238 | BH01 B390 | B390/1 | Ceres | Blaawbosch Kalk | −60.05 | −210.9 | 8.8 | 5.9 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |

| 872239 | BH02 B390 | B390/1 | Ceres | Blaawbosch Kalk | −51.6 | −164 | 0.89 | 0.60 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |

| 872240 | BH03 B390 | B390/1 | Ceres | Blaawbosch Kalk | 0.0098 | 0.0065 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0006 | |||

| 872241 | BH 01 SA | SA 1/66 | Merweville | Sambokraal | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872242 | BH 02 SA | SA 1/66 | Merweville | Sambokraal | <0.0006 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872243 | BH 03 SA | SA 1/66 | Merweville | Sambokraal | −40.6 | −113 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.0013 | 0.0016 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |

| 872244 | KDD | KDD | Beaufort West | Beaufort West | −30.39 | −245.7 | −36.7 | 16 | 11 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.010 | 0.019 |

| 872245 | BO4H-BW | KDD | Beaufort West | Beaufort West | 0.067 | 0.045 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872246 | BO2H-BW | KDD | Beaufort West | Beaufort West | 0.0015 | 0.00098 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872247 | SPF-BW | KDD | Beaufort West | Beaufort West | 0.0056 | 0.0037 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872248 | BH01KW | KW 1/67 | Prince Albert | Klein Waterval | 0.0052 | 0.0034 | <0.0002 | <0.0002 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | |||

| 872249 | BH02KW | KW 1/67 | Prince Albert | Klein Waterval | 0.0093 | 0.0062 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872250 | BH01VR | VR 1/66 | Graaff Reinet | Vrede | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872251 | BH02VR | VR 1/66 | Graaff Reinet | Vrede | 0.050 | 0.034 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872252 | BH03VR | VR 1/66 | Graaff Reinet | Vrede | <0.0005 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872253 | BH04VR | VR 1/66 | Graaff Reinet | Vrede | −45.02 | −183.0 | 19 | 13 | 0.00075 | 0.00094 | <0.0004 | <0.0007 | |

| 872254 | BH01SC | SC 3/67 | Aberdeen | Skietfontein | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.00042 | 0.00052 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872255 | BH02SC | SC 3/67 | Aberdeen | Skietfontein | 0.097 | 0.065 | 0.00100 | 0.0012 | <0.0003 | <0.0006 | |||

| 872256 | BH03SC | SC 3/67 | Aberdeen | Skietfontein | 0.0080 | 0.0053 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872257 | BH04SC | SC 3/67 | Aberdeen | Skietfontein | 0.0034 | 0.0023 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872258 | BH05SC | SC 3/67 | Aberdeen | Skietfontein | 0.0016 | 0.0011 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872259 | BH01KA | KA 1/65 | Murraysburg | Karee Bosch | −29.96 | −203.3 | −25.3 | 24 | 16 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.00085 | 0.0016 |

| 872260 | BH02KA | KA 1/65 | Murraysburg | Karee Bosch | 0.068 | 0.046 | <0.0005 | <0.0006 | <0.0005 | <0.0008 | |||

| 872261 | BH03KA | KA 1/65 | Murraysburg | Karee Bosch | 0.037 | 0.025 | <0.0004 | <0.0005 | <0.0004 | <0.0007 | |||

| 872262 | KA 1/65 | KA 1/65 | Murraysburg | Karee Bosch | −27.85 | −220.3 | −35.1 | 17 | 11 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.020 | 0.037 |

| 872263 | BH01AB | AB 1/65 | Victoria West | Abrahamskraal | 0.091 | 0.061 | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872264 | BH02AB | AB 1/65 | Victoria West | Abrahamskraal | 0.0039 | 0.0026 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872265 | BH 01 KD | KD 1/71 | Carnarvon | Heuwels | 0.0048 | 0.0032 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872266 | BH 02 KD | KD 1/71 | Carnarvon | Heuwels | <0.0006 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872267 | BH 03 KD | KD 1/71 | Carnarvon | Heuwels | 0.0091 | 0.0061 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872268 | BH 04 KD | KD 1/71 | Carnarvon | Heuwels | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872269 | BH01AM | AM1/70 | Williston | Amersfontein | 0.013 | 0.0085 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872270 | BH02AM | AM1/70 | Williston | Amersfontein | 0.0031 | 0.0021 | <0.0005 | <0.0006 | <0.0004 | <0.0008 | |||

| 872271 | BH03AM | AM1/70 | Williston | Amersfontein | 0.0013 | 0.00088 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872272 | BH04AM | AM1/70 | Williston | Amersfontein | 0.00093 | 0.00062 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872273 | BH01KC | KC 1/71 | Calvinia | Kwaggasfontein | −63.4 | 0.19 | 0.13 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | ||

| 872274 | BH02KC | KC 1/71 | Calvinia | Kwaggasfontein | 0.0033 | 0.0022 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0006 | |||

| 872275 | BH03KC | KC 1/71 | Calvinia | Kwaggasfontein | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872276 | BH04KC | KC 1/71 | Calvinia | Kwaggasfontein | <0.0006 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0006 | |||

| 872277 | Qu 1/65 | Qu 1/65 | Frasersburg | Quaggasfontein | −18.27 | −227.9 | −22.3 | 13 | 8.5 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.018 | 0.032 |

| 872278 | BH01Qu1 | Qu 1/65 | Frasersburg | Quaggasfontein | 0.0029 | 0.0019 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872279 | BH02Qu1 | Qu 1/65 | Frasersburg | Quaggasfontein | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872280 | BH03Qu1 | Qu 1/65 | Frasersburg | Quaggasfontein | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | |||

| 872281 | BH04Qu1 | Qu 1/65 | Frasersburg | Quaggasfontein | 0.030 | 0.020 | <0.0003 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872282 | BH 01 Qu2 | Qu 2/65 | Frasersburg | Beeswater | 0.024 | 0.016 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.00052 | 0.00096 | |||

| 872283 | BH 02 Qu2 | Qu 2/65 | Frasersburg | Beeswater | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | <0.0005 | <0.0009 | |||

| 872284 | BH 03 Qu2 | Qu 2/65 | Frasersburg | Beeswater | −50.14 | −334 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | <0.0004 | <0.0008 | |

| 872285 | BH 04 Qu2 | Qu 2/65 | Frasersburg | Beeswater | 0.0032 | 0.0022 | <0.0003 | <0.0004 | <0.0003 | <0.0006 | |||

| 872286 | BH 05 Qu2 | Qu 2/65 | Frasersburg | Beeswater | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0003 | <0.0002 | <0.0004 | |||

| 872287 | KL 1/65 | KL 1/65 | Sutherland | Klip Drift | −29.60 | −240.0 | −31.3 | 13 | 8.8 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.0094 | 0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mugivhi, M.; Kanyerere, T.; Xu, Y.; Moore, M.T.; Hackley, K.; Mabidi, T.; Baloyi, L. Abandonment Integrity Assessment Regarding Legacy Oil and Gas Wells and the Effects of Associated Stray Gas Leakage on the Adjacent Shallow Aquifer in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Hydrology 2026, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010014

Mugivhi M, Kanyerere T, Xu Y, Moore MT, Hackley K, Mabidi T, Baloyi L. Abandonment Integrity Assessment Regarding Legacy Oil and Gas Wells and the Effects of Associated Stray Gas Leakage on the Adjacent Shallow Aquifer in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleMugivhi, Murendeni, Thokozani Kanyerere, Yongxin Xu, Myles T. Moore, Keith Hackley, Tshifhiwa Mabidi, and Lucky Baloyi. 2026. "Abandonment Integrity Assessment Regarding Legacy Oil and Gas Wells and the Effects of Associated Stray Gas Leakage on the Adjacent Shallow Aquifer in the Karoo Basin, South Africa" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010014

APA StyleMugivhi, M., Kanyerere, T., Xu, Y., Moore, M. T., Hackley, K., Mabidi, T., & Baloyi, L. (2026). Abandonment Integrity Assessment Regarding Legacy Oil and Gas Wells and the Effects of Associated Stray Gas Leakage on the Adjacent Shallow Aquifer in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Hydrology, 13(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010014