Suspension Type TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Submillimeter TiO2-Polystyrene Beads

Abstract

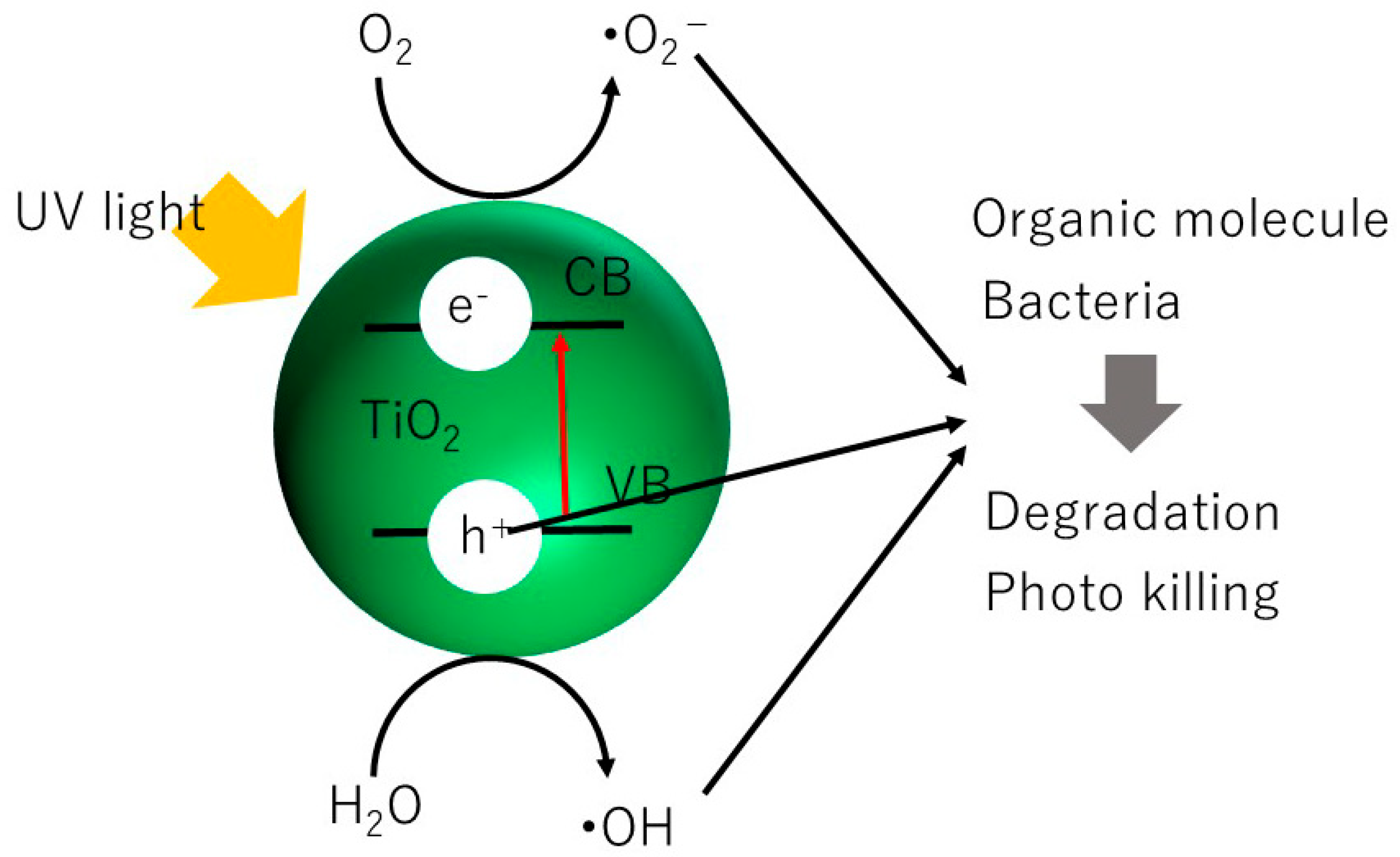

1. Introduction

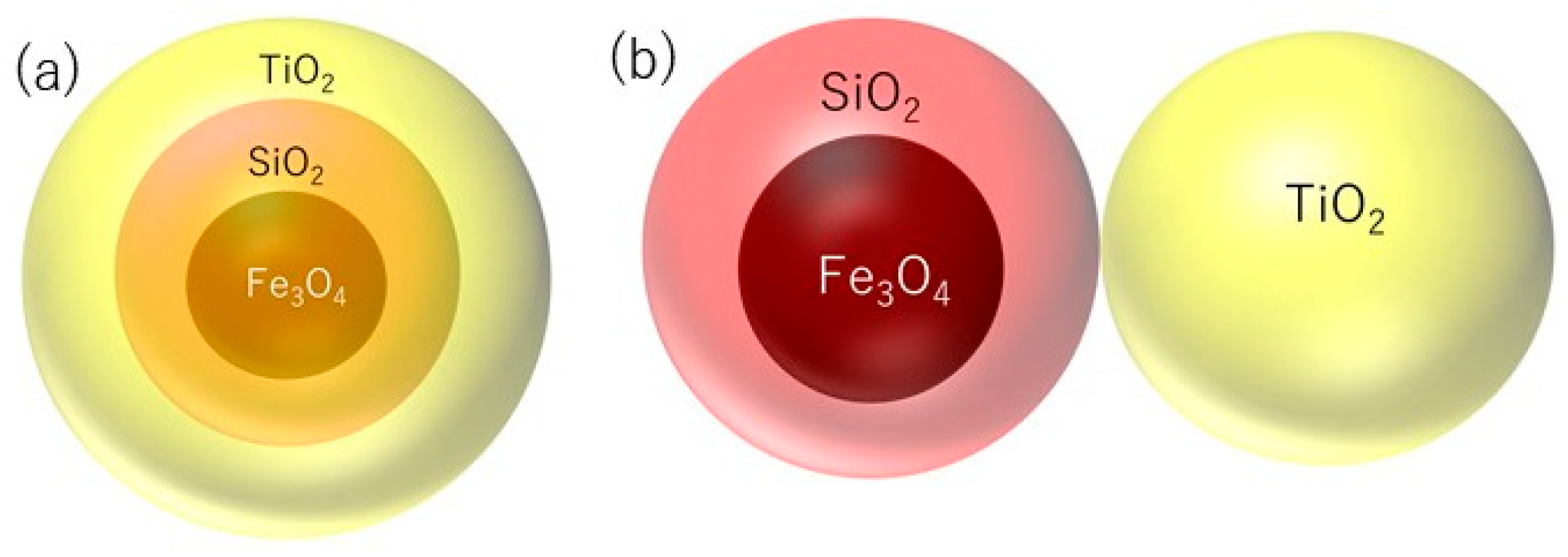

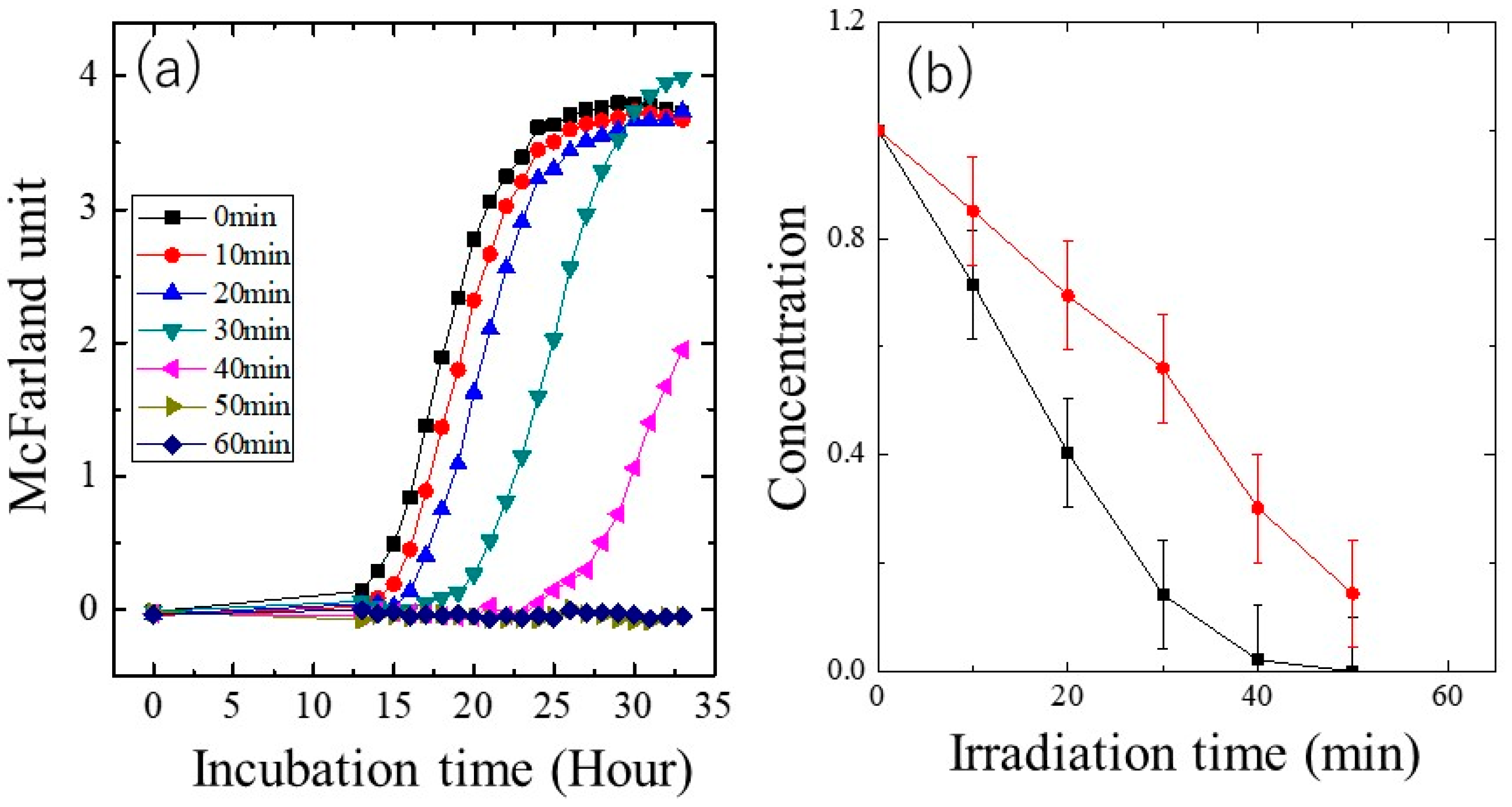

2. Nano Sized Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Photocatalysts

2.1. Preparation

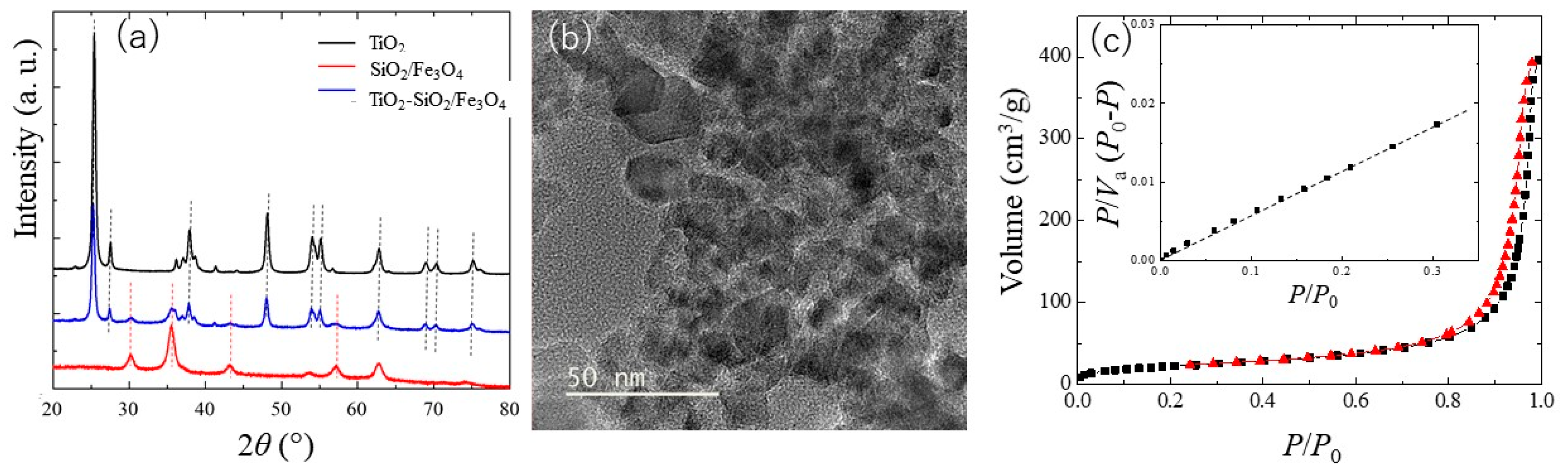

2.2. Characterization

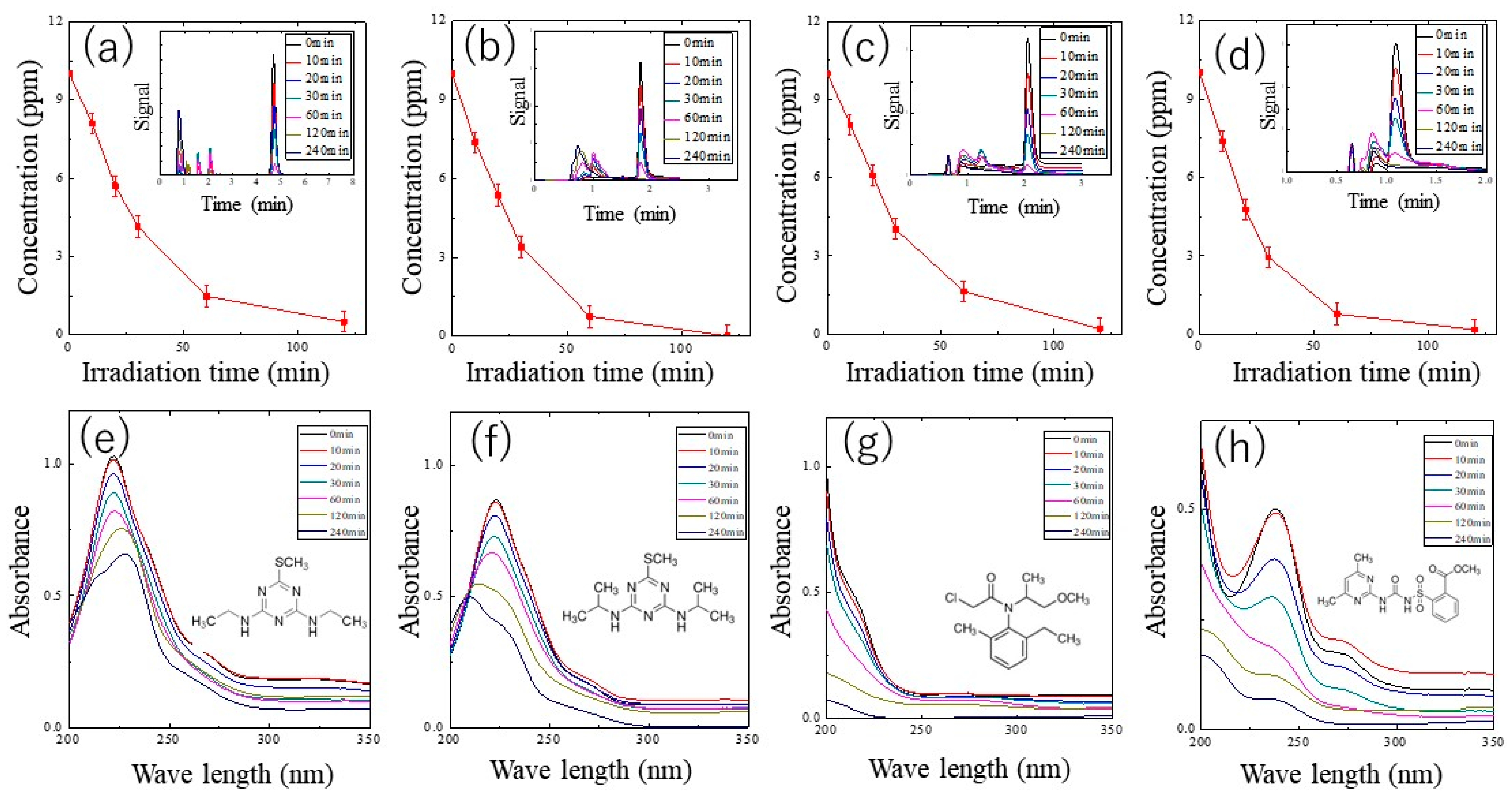

2.3. Photocatalytic Performance

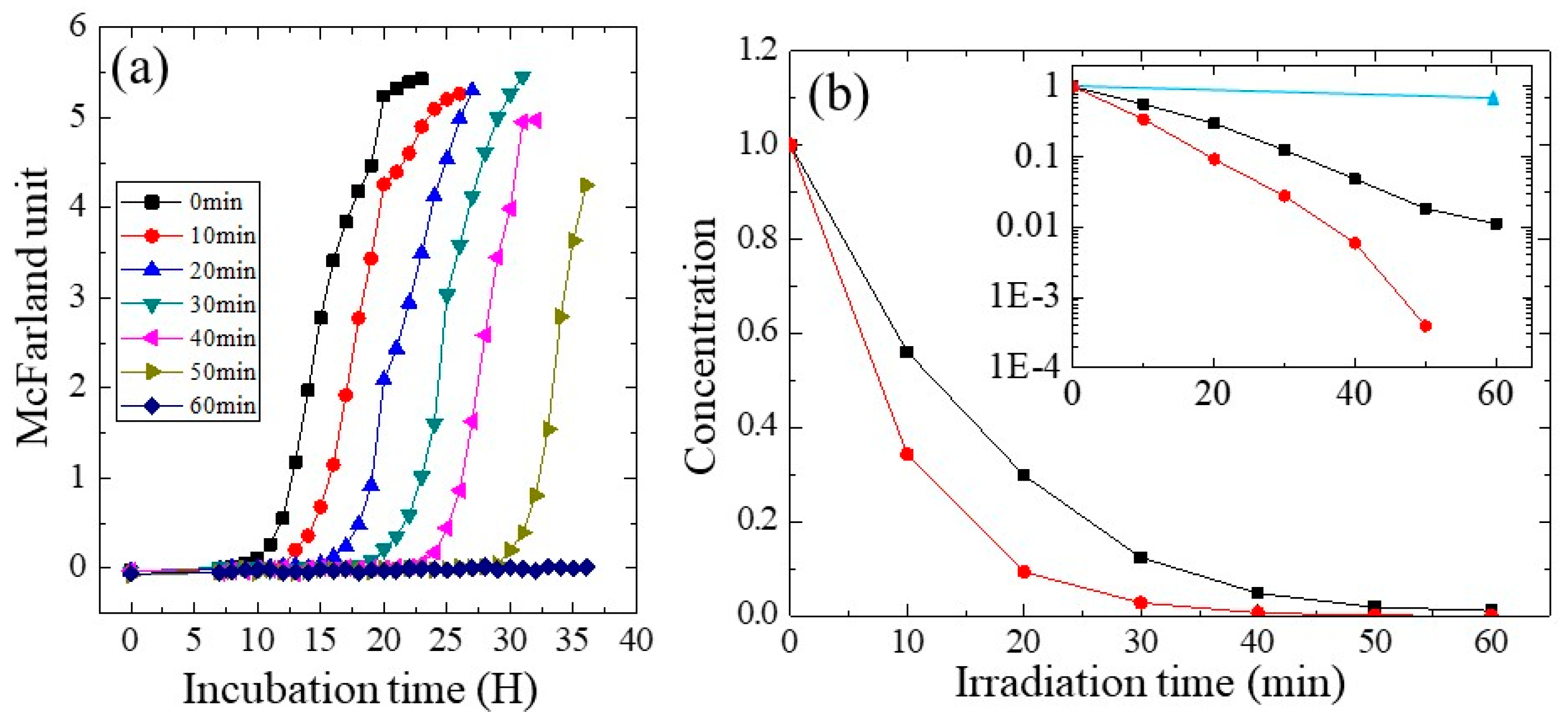

3. Submillimeter Scale TiO2-Polystyrene Beads Photocatalysts

3.1. Preparation

3.2. Photocatalytic Performance

4. Comparison Between Two Type Photocatalysts and Future Perspective

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, T.P.; Nguyen, D.L.T.; Nguyen, V.; Le, T.; Vo, D.N.; Trinh, Q.T.; Bae, S.; Chae, S.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Le, Q.V. Recent Advances in TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Reduction of CO2 to Fuels. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Gareso, P.L.; Armynah, B.; Tahir, D. A review of TiO2 photocatalyst for organic degradation and sustainable hydrogen energy production. Inter. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmy, A.V.; Anandakumar, V.M.; Biju, V. Enhancing the visible-light sensitive photocatalysis of anatase TiO2 through surface-modification. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, V.; Galatonova, T.; Braniste, T.; Urbanek, P.; Lehmann, S.; Hanulikova, B.; Nielsch, K.; Kuritka, I.; Sedlarik, V.; Tiginyanu, I. Aero-TiO2 three-dimensional nanoarchitecture for photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, O.; Maghsoodi, M.; Jang, S.S.; Snow, S.D. Unveiling Competitive Adsorption in TiO2 Photocatalysis through Machine-Learning-Accelerated Molecular Dynamics, DFT, and Experimental Methods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 36215–36223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Sakata, T. Conversion of carbohydrate into hydrogen fuel by a photocatalytic process. Nature 1980, 286, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, H.; Fujishima, A. Studies on photokilling of bacteria on TiO2 thin film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 8269–8285. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Fujishima, A.; Chikuni, M.; Kojima, E.; Kitamura, A.; Shimohigoshi, M.; Watanabe, T. Light-induced amphiphilic surfaces. Nature 1997, 388, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Ochiai, T.; Hamada, K.; Tryk, D.A.; Terashima, C.; Suzuki, N.; Tsunoda, K.; Ishiguro, H.; Zhi, J.; Kim, J.; et al. The latest information in simple terms. In Photocatalysis Experimental Methods; Kitano Book: Kawasaki City, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New understanding of the difference of photocatalytic activity among anatase, rutile and brookite TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.A.; Qasim, K.F.; Alshorifi, F.T.; El-Bahy, S.M.; Salama, R.S. Role of NiO Nanoparticles in Enhancing Structure Properties of TiO2 and Its Applications in Photodegradation and Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 30386–30400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, M.; Zava, M.; Grande, T.; Prina, V.; Monticelli, D.; Roncoroni, G.; Rampazzi, L.; Hildebrand, H.; Altomare, M.; Schmuki, P.; et al. Enhanced Photocatalytic Paracetamol Degradation by NiCu-Modified TiO2 Nanotubes: Mechanistic Insights and Performance Evaluation. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, T.; Nosaka, Y. Properties of O2 and OH Formed in TiO2 Aqueous Suspensions by Photocatalytic Reaction and the Influence of H2O2 and Some Ions. Langmuir 2002, 18, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, T.; Yawata, K.; Nosaka, Y. Photocatalytic reactivity for O2 and OH radical formation in anatase and rutile TiO2 suspension as the effect of H2O2 addition. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 325, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanourakis, S.K.; Peña-Bahamonde, J.; Bandara, P.C.; Rodrigues, D.F. Nano-based adsorbent and photocatalyst use for pharmaceutical contaminant removal during indirect potable water reuse. NPJ Clean Water 2020, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Wen, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Long, T. A critical review on challenges and trend of ultrapure water production process. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 78, 147254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.; Xiao, S.; Yu, X.; Dong, C.; Ji, J.; Zhang, D.; Xing, M. Research progress of photocatalytic sterilization over semiconductors. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19278–19284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, G.; Zheng, S.; Gao, X.; Xiang, Z.; Gao, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Zhong, J. Advanced photocatalytic disinfection mechanisms and their challenges. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmao, C.; Palharim, P.H.; Diniz, L.A.; de Assis, G.C.; Souza, T.d.C.E.; Ramos, B.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C. Advances in Fluidized Bed Photocatalysis: Bridging Gaps, Standardizing Metrics, and Shaping Sustainable Solutions for Environmental Challenges. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 14967–14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, M.J.; Ferreira, L.F.; Silva, V.C. Magnetic materials for photocatalytic applications—A review. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, D.; Amal, R.; Scott, J.; Low, G.; McEvoy, S. Studies on the Mineralization and Separation Efficiencies of a Magnetic Photocatalyst. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2001, 24, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belessiotis, G.V.; Falara, P.P.; Ibrahim, I.; Kontos, A.G. Magnetic Metal Oxide-Based Photocatalysts with Integrated Silver for Water Treatment. Materials 2022, 15, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Chou, X.; Zhang, W.; Ye, H.; Cui, Z.; Dobson, P.J. High Photocatalytic Activity of Fe3O4-SiO2-TiO2 Functional Particles with Core-Shell Structure. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 62423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi, M.; Wang, J.; Yuxin, L.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Z.; Ma, M.; Fujishima, A.; Hanada, N. Nano-sized magnetic TiO2-SiO2/Fe3O4 Photocatalysts and their application to photokilling of Lactobacillus casei and photocatalytic degradation of persistent herbicides. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miądlicki, P.; Rychtowski, P.; Tryba, B. Coating of expanded polystyrene spheres by TiO2 and SiO2–TiO2 thin films. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 1473–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi, M.; Liang, Z.; Ma, M.; Fujishima, A.; Hanada, N. Polystyrene beads photocatalysts drifting in water by small perturbation and their application to photokilling of Lactobacillus casei. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2025, 467, 116417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelica, I.; Curkovic, L.; Mandic, V.; Panzic, I.; Ljubas, D.; Rapid, K. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Core-2-Layer-Shell Nanocomposite for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Kiguchi, M.; Liang, Z.; Ma, M.; Fujishima, A.; Hanada, N. Photocatalytic Degradation of Triazine Herbicides in Agricultural Water Using Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Photocatalyst: Phytotoxicity Assessment in Pak Choi. ACS Omega 2025, 40, 47471–47480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembiring, T.; Lubis, H.; Lubis, Y.R.; Sihite, T.J.; Sebayang, K.; Marlianto, E. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 using coprecipitation method. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2561, p. 020004. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama, S.; Shariati, S.; Divsar, F. Synthesis of Functionalized Magnetite Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposite for Removal of Acid Fuchsine Dye. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2018, 21, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absalan, F.; Nikazar, M. Application of Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Water Treatment by Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Core-Shell Nano-Photocatalyst. Chem. Eng. Comm. 2016, 203, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisli, A.; Ridwan; Krisnandi, Y.K.; Gunlazuardi, J. Preparation and characterization of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2composite for methylene blue removal in water. Inter. J. Tech. 2017, 1, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunlazuardi, J.; Fisli, A.; Ridwan; Krisnandi, Y.K.; Robert, D. Magnetically Separable Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Photocatalyst Composites Prepared through Hetero Agglomeration for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Paraquat. Makara J. Sci. 2021, 25, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiari, N.; Kashefi, M.; Afsharnezhad, S.; Mirjalili, M. Insight into enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of Fe3O4–SiO2–TiO2 core-multishell nanoparticles on the elimination of Escherichia coli. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2020, 244, 122633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ying, J.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, G.; Qu, X. Synthesis of 1D magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2/TiO2 nanostir bar photocatalyst for the degradation of MB under UV light. Mater. Lett. 2024, 364, 136344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziltas, H.; Tekin, T.; Tekin, D. Preparation and characterization of recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 composite photocatalyst, and investigation of the photocatalytic activity. Chem. Eng. Comm. 2021, 208, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Xi, X.; Hu, R.; Jiang, G. Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Magnetic Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Composites. Adv. Mat Sci. Eng. 2012, 2012, 409379. [Google Scholar]

- Vahidian, H.R.; Zarei, A.R.; Soleymani, A.R. Degradation of nitro-aromatic explosives using recyclable magnetic photocatalyst: Catalyst synthesis and process optimization. J. Hazard Mat. 2016, 325, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Tsai, P.; Chen, Y. Functional Fe3O4/TiO2 Core/Shell Magnetic Nanoparticles as Photokilling Agents for Pathogenic Bacteria. Small 2008, 4, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanda, Y.; Nuryono, N.; Kunarti, E.S. Synthesis and Application of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanocomposite as a Photocatalyst in CO2 Indirect Reduction to Produce Methanol. Indones. J. Chem. 2019, 19, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, T.A.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Byrne, J.A. The photocatalytic degradation of atrazine on nanoparticulate TiO2 films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2006, 182, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmeier, W.; Ohrbach, K.H.; Kuhn, P.; Kettrup, A. Investigations into the thermal decomposition of selected pesticides. J. Anal. Appl. Pyroijsis 1989, 16, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, V.A.; Arabatzis, I.M.; Konstantinou, I.K.; Dimou, A.D.; Albanis, T.A.; Falaras, P. Metolachlor photocatalytic degradation using TiO2 photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B 2004, 49, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, D.O.; Mendes, K.F.; Tosi, M.; de Souza, L.F.; Cedano, J.C.C.; Falcão, N.P.d.S.; Dunfield, K.; Tsai, S.M.; Tornisielo, V.L. Sorption-desorption and biodegradation of sulfometuron-methyl and its effects on the bacterial communities in Amazonian soils amended with aged biochar. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varnagiris, S.; Urbonavicius, M.; Sakalauskaite, S.; Daugelavicius, R.; Pranevicius, L.; Lelis, M.; Milcius, D. Floating TiO2 photocatalyst for efficient inactivation of E. coli and decomposition of methylene blue solution. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, F.; Lago, R.M. Floating photocatalysts based on TiO2 grafted on expanded polystyrene beads for the solar degradation of dyes. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 1521–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altın, I.; Sökmen, M. Preparation of TiO2-polystyrene photocatalyst from waste material and its usability for removal of various pollutants. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2014, 144, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandova, G.M.H.; Baez-Angarita, D.B.; Torres, S.N.C.; Pedrozo, O.M.P.; Rivera, S.P.H. Novel EPS/TiO2 Nanocomposite Prepared from Recycled Polystyrene. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2013, 4, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, N.; Takahashi, T.; Terui, N.; Furukawa, S. Synthesis of Polystyrene@TiO2 Core–Shell Particles and Their Photocatalytic Activity for the Decomposition of Methylene Blue. Inorganics 2023, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiyi, M.E.; Skelton, R.L. Photocatalytic mineralisation of methylene blue using buoyant TiO2-coated polystyrene beads. J. Photochem. Photobio. A 2000, 132, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chaki, A.; Chand, D.P.; Raghuwanshi, A.; Singh, P.K.; Mahalingam, H. A novel polystyrene-supported titanium dioxide photocatalyst for degradation of methyl orange and methylene blue dyes under UV irradiation. J. Chem. Eng. IEB 2013, 28, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mahalingam, H. An Effective and Low-Cost TiO2/Polystyrene Floating Photocatalyst for Environmental Remediation. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Rincon, G.J.; La Motta, E.J. A fluidized-bed reactor for the photocatalytic mineralization of phenol on TiO2-coated silica gel. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.P.; Yang, T.H.; Wang, J.C.; Chuang, H.S. Recent trends and innovations in bead-based biosensors for cancer detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinero-Fernández, Á.; Moreno-Guzmán, M.; López, M.Á.; Escarpa, A. Magnetic bead-based electrochemical immunoassays on-drop and on-chip for procalcitonin determination: Disposable tools for clinical sepsis diagnosis. Biosensors 2020, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenea-Robin, M.; Marchalot, J. Basic principles and recent advances in magnetic cell separation. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begines, B.; Ortiz, T.; Pérez-Aranda, M.; Martínez, G.; Merinero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Alcudia, A. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery: Recent developments and future prospects. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandayuthapani, B.; Yoshida, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Kumar, D.S. Polymeric scaffolds in tissue engineering application: A review. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2011, 19, 290602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, M.; Mahalingam, H. Upcycling of waste EPS beads to immobilized codoped TiO2 photocatalysts for ciprofloxacin degradation and E. coli disinfection under sunlight. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boochakiat, S.; Inceesungvorn, B.; Nattestad, A.; Chen, J. Bismuth-Based Oxide Photocatalysts for Selective Oxidation Trans formations of Organic Compounds. ChemNanoMat 2023, 9, e202300140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Jiang, W.; Huang, M.; He, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y. Progress in Preparation, Identification and Photocatalytic Application of Defective g-C3N4 Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 510, 215849. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Ou, X.; Xiang, Q.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Fan, J.; Lv, K. Research Progress in Metal Sulfides for Photocatalysis: From Activity to Stability. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yu, X.Y.; Lou, X.W. The Design and Synthesis of Hollow Micro-/Nanostructures: Present and Future Trends. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Arunachalam, P.; Ramachandran, K.; Al Mayouf, A.M.; Karuppuchamy, S. Recent Advances in Semiconductor Metal Oxides with Enhanced Methods for Solar Photocatalytic Applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 828, 154281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Cattarin, S.; Loglio, F.; Cecconi, T.; Seravalli, G.; Foresti, M.L. Ternary Cadmium and Zinc Sulfides: Composition, Morphology and Photoelectrochemistry. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 49, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Taga, Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, W.; Park, H.; Tachikawa, T.; Majima, T.; Choi, W. Carbon-doped TiO2 photocatalyst synthesized without using an external carbon precursor and the visible light activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 91, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.K.; Nam, I.-S.; Park, J.M. (Eds.) New Developments and Application in Chemical Reaction Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anpo, M.; Takeuchi, M. Design and development of second-generation titanium oxide photocatalysts to better our environment—Approaches in realizing the use of visible light. Int. J. Photoenergy 2001, 3, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, G. Magnetic photocatalysts of cenospheres coated with Fe3O4/TiO2 core/shell nanoparticles decorated with Ag nanopartilces. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 8547–8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, P.Y.; Mao, S.S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science 2011, 331, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Dua, G.; Kalam, A.; Sun, D.; Yu, Y.; Su, Q.; Xu, B.; Al-Sehemi, A.G. Tuning oxygen vacancy content in TiO2 nanoparticles to enhance the photocatalytic performance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 234, 116440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Du, T.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Wang, J. Recent advances on heterojunction-based photocatalysts for the degradation of persistent organic pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 130617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tan, Q.; Liu, T.; He, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, K.; Han, D.; Qinb, D.; Niu, L. Fabrication of water-floating litchi-like polystyrene-sphere-supported TiO2/Bi2O3 S-scheme heterojunction for efficient photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Khan, M.; Fang, L.; Lo, I.M.C. Visible-light-driven N-TiO2@SiO2@Fe3O4magneticnanophotocatalysts: Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalyticdegradation of PPCPs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 370, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osanloo, M.; Khorasheh, F.; Larimi, A. Fabrication of nano-dandelion magnetic TiO2/CuFe2O4 doped with silver as a highly visible-light-responsive photocatalyst for degradation of Naproxen and Rhodamine B. J. Mol. Liquids 2024, 407, 125242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Guan, W.; Zhang, G.; Ye, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X. TiO2/Fe2O3/CNTs magnetic photocatalyst: A fast and convenient synthesis and visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. Micro Nano Lett. 2013, 8, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Shape | Synthesis Method | Particle Size | Surface Area (BET) | Saturation Magnetization | Target Pollutants | Light Source | Apparent Rate Constants or Degradation Percentage/Time | Recyclability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core-shell | Sol-gel | 200 nm | 446.87 m2/g | MB, MO | UV lamp 20 W Energy intensity 200 mW/cm2 | 0.129/min | 5 times 95% | [37] | |

| Core-shell | Solvothermal | 240 nm | 44 emu/g | Acid Blue | UV lamp | 91% 180 min | [38] | ||

| Core-shell | Sol-gel | Pomegranate like structure | MB | High-pressure mercury lamp 100 W Wavelength 290–450 nm | 78% 5 min | [39] | |||

| Core-shell | Sol-gel | 22 nm | 12 emu/g | Nitrophenol | UV-C light 150 W Wavelength 254 nm | 0.032/min | 4 cycle 92% | [40] | |

| Core–shell | Microwave assisted sol-gel | Porous microstructure | 17 emu/g | Ciprofloxacin | UVA lamp Wavelength 365 nm | 0.0158/min | 3 cycle 97% | [29] | |

| Core-shell | Sol-gel | JRS4 S. Saprophyticus S. pyogenes M9022434 S. pyogenes M9141204 S. aureus | UVB lamp Main wavelength 306 nm Energy intensity 0.412 mW/cm2 | 20 min Survival ratio JRS4 6% S. saprophyticus 0.5% S. pyogenes M9022434 4% S. pyogenes M9141204 26% S. aureus 7% | [41] | ||||

| Peanut | Hetero Agglomeration P25 | 20 nm | 79 m2/g | MB | LED lamp: 365 nm (40 mW/cm2) | 0.055/min | 5 cycles | [26] | |

| Peanut | Hetero Agglomeration P25 | 25 nm | 86.1 m2/g | 17.43 emu/g | Paraquat | UV lamp 2 × 18 W Main wavelength 254 nm | [35] |

| Floating vs. Suspended | Bead Size and Density | TiO2 Loading | Target Pollutants | Light Source | Stirring or no Stirring | Degradation Performance | Recyclability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floating EPS | 5–12 nm | MB | UV light wave length 254 nm | stirring | 9.05 × 10−3/min | [50] | ||

| Suspended | 290 nm | MB | UV lamp (365 nm) with (150 mW cm−2) | stirring | 3.67%/min | [51] | ||

| Suspended | 615 μm Density 0.62 gm/cm3 | 10:1 volume ratio of TiO2 to polystyrene | MB | Low-pressure mercury lamp 30 W Main wavelength 254 nm | stirring | 0.3 μmol/min | 10 | [52] |

| Floating | 2–4 mm | 18% | MB | Hg lamp Main wavelength 254 nm 15 W | no stirring | 10 × 10−5 g/L min | 5 | [48] |

| Suspended | 500–800 μm | 3% | Escherichia coli | UV-A lamp Wave length 365 nm | stirring | 89% of E. coli after 60 min exposure | 5 | [49] |

| Suspended | 200 nm | MB | LED light 216 W Wave length 365 nm | stirring | 0.11/min | 3 | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kiguchi, M.; Hanada, N. Suspension Type TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Submillimeter TiO2-Polystyrene Beads. ChemEngineering 2026, 10, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010003

Kiguchi M, Hanada N. Suspension Type TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Submillimeter TiO2-Polystyrene Beads. ChemEngineering. 2026; 10(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiguchi, Manabu, and Nobuhiro Hanada. 2026. "Suspension Type TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Submillimeter TiO2-Polystyrene Beads" ChemEngineering 10, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010003

APA StyleKiguchi, M., & Hanada, N. (2026). Suspension Type TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: Magnetic TiO2/SiO2/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Submillimeter TiO2-Polystyrene Beads. ChemEngineering, 10(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010003