Drying Methods Applied to Ionic Gelation of Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa) Pulp Microcapsules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Characterization

2.2. Preparation of Microcapsules

2.3. Drying

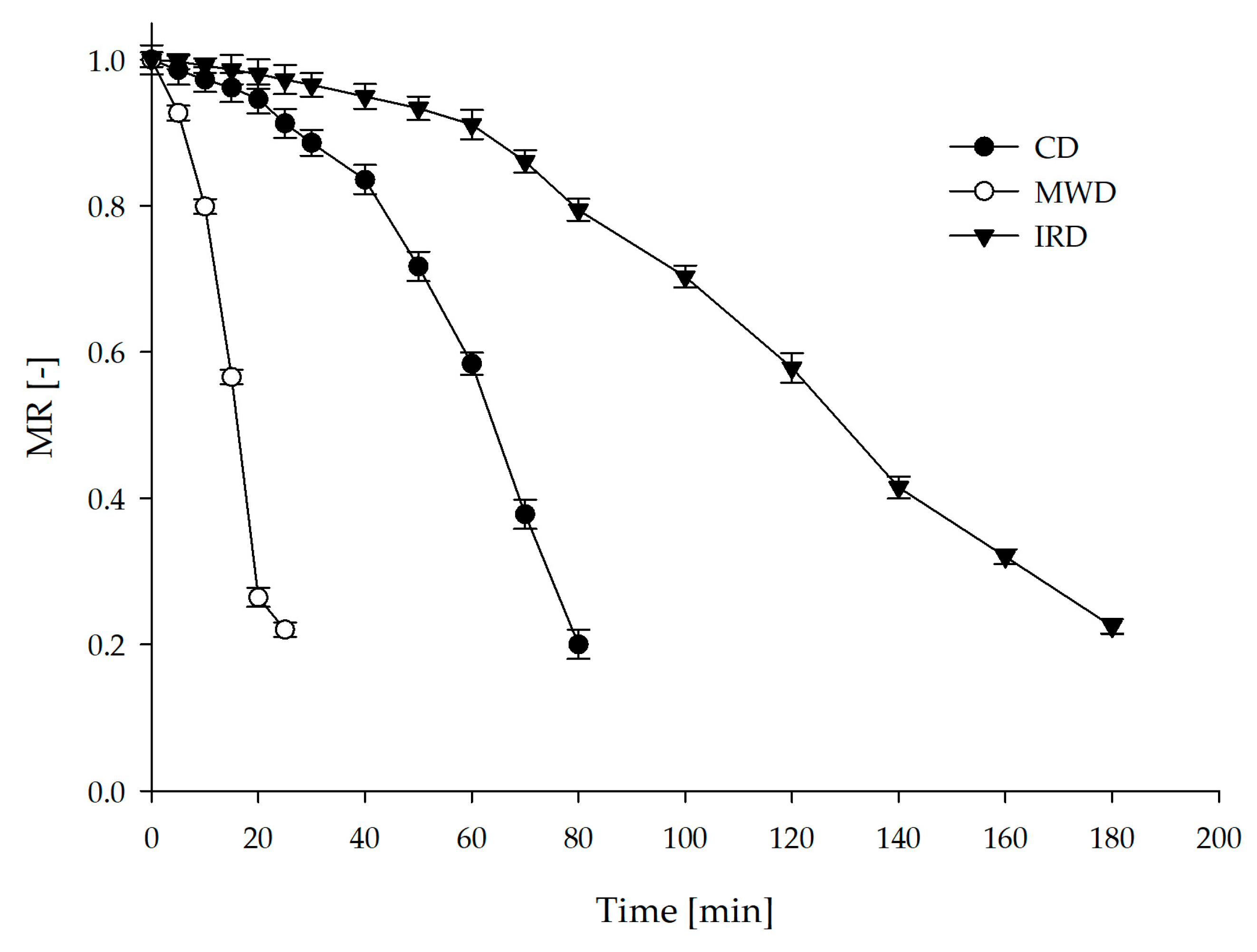

2.4. Drying Kinetics and Mathematical Modeling

| Equation Name | Equation | |

|---|---|---|

| Newton | (2) | |

| Page | (3) | |

| Page modified | (4) | |

| Henderson and Pabis | (5) | |

| Wang-Singh | (6) | |

| Diffusion Approach | (7) |

2.5. Physical Characterization

2.5.1. Dispersibility

2.5.2. Wettability

2.5.3. Hygroscopicity

2.5.4. Solubility and Water Absorption Index

2.5.5. Bulk Density, Particle Density and Porosity

2.5.6. Color Parameters

2.6. Bioactive Compounds

2.6.1. Total Phenolic and Antioxidant Activity

2.6.2. Ascorbic Acid

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fruit Characterization and Ionic Gelation

3.2. Drying Kinetics and Mathematical Modeling

3.3. Physical Characterization

3.3.1. Dispersibility and Wettability

3.3.2. Hygroscopicity and WAI

3.3.3. Bulk (ρb) and Particle (ρp) Densities and Porosity (ε)

3.3.4. Color Parameters

3.4. Bioactive Compounds

4. General Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Convective Drying |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| IC50 | Inhibitory Concentration 50% |

| IRD | Infrared Drying |

| MR | Moisture Reduction |

| MWD | Microwave Drying |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| WAI | Water Absorption Index |

References

- Reis, A.F.; Schmiele, M. Characteristics and Potentialities of Savanna Fruits in the Food Industry. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22, e2017150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.; dos Santos Freitas, L.; Silva Santana, J.G.; Muniz, E.N.; Rabbani, A.R.C.; da Silva, A.V.C. Genetic Diversity and the Quality of Mangabeira Tree Fruits (Hancornia speciosa Gomes—Apocynaceae), a Native Species from Brazil. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 226, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, V.H.N.S.; da Silva Mazzeti, C.M.; Rodrigues, B.M.; de Souza, H.S.; Correa, A.D.; de Almeida Mello, M.; de Oliveira, C.F.R.; de Orlandi Sardi, J.C.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; La Flor Ziegler Sanches, F.; et al. Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa): Exploring Potent Antifungal and Antioxidant Properties in Lyophilised Fruit Pulp Extract through in Vitro Analysis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 39, 6432–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.S.; Silva, L.S.; Barros, F.P.D.; Rodrigues Filho, D.P.; Barros, S.K.A.; Pinedo, A.A.; Zuniga, A.D.G.; Dantas, V.V. Avaliação Dos Parâmetros Físicos Químicos de Geleia Mix de Polpas de Cagaita (Eugenia dysenterica) e Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa). Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e581101624226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Santos, K.S.; Borges, G.R.; Muniz, A.V.C.S.; Mendonça, F.M.R.; Pinheiro, M.S.; Franceschi, E.; Dariva, C.; Padilha, F.F. Separation of Antibacterial Biocompounds from Hancornia speciosa Leaves by a Sequential Process of Pressurized Liquid Extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 222, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis VHde, O.T.; Rodrigues, B.M.; Loubet Filho, P.S.; Cazarin, C.B.B.; Rafacho, B.P.M.; Santosa, E.F.D. Biotechnological Potential of Hancornia speciosa Whole Tree: A Narrative Review from Composition to Health Applicability. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiassi, M.C.E.V.; Souza, V.R.d.e.; Lago, A.M.T.; Campos, L.G.; Queiroz, F. Fruits from the Brazilian Cerrado Region: Physico-Chemical Characterization, Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activities, and Sensory Evaluation. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Brahmia, A.; Shahbaz, A.; Sahramaneshi, H.; Alkhalifah, T.; Yang, J. A Novel Machine Learning Model for Innovative Microencapsulation Techniques and Applications in Advanced Materials, Textiles, and Food Industries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.E.; Tamer, T.M.; Valachová, K.; Šoltés, L. Microencapsulation Process: Methods, Properties, and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Silveira, M.; Lucas Chaves Almeida, F.; Dutra Alvim, I.; Silvia Prata, A. Encapsulation of Pomegranate Polyphenols by Ionic Gelation: Strategies for Improved Retention and Controlled Release. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; McClements, D.J.; Luo, S.; Ye, J.; Liu, C. Effect of Internal and External Gelation on the Physical Properties, Water Distribution, and Lycopene Encapsulation Properties of Alginate-Based Emulsion Gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Andreola, K.; Alvim, I.D.; de Moura, S.C.S.R.; Hubinger, M.D. Microencapsulation of Pitanga Extract (Eugenia uniflora L.) by Ionic Gelation: Effect of Wall Material and Fluidized Bed Drying. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Ortiz-Basurto, R.I.; Chacón-López, M.A.; Martinez-Gutierrez, F.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A.; Montalvo-González, E.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Effect of the Drying Methods on the Stabilization of Symbiotic Microbeads Produced by Ionic Gelation. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozawa, L.E.; Hubinger, M.D. Hydrophilic Food Compounds Encapsulation by Ionic Gelation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 15, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Junqueira, J.R.; Balbinoti, T.C.V.; Santos, A.A.L.; Campos, R.P.; Miyagusku, L.; Corrêa, J.L.G. Infrared Drying of Canjiqueira Fruit: A Novel Approach for Powder Production. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, M.G.; Singh, A.; Kumar, N.; Dhenge, R.V.; Rinaldi, M.; Chinchkar, A.V. Semi-Empirical Mathematical Modeling, Energy and Exergy Analysis, and Textural Characteristics of Convectively Dried Plantain Banana Slices. Foods 2022, 11, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ramos, F.; Leiva-Portilla, D.; Rodríguez-Núñez, K.; Pacheco, P.; Briones-Labarca, V. Mathematical Modeling and Quality Parameters of Salicornia fruticosa Dried by Convective Drying. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Santos, A.A.; de Souza Cruz, M.; Santos, J.C.C.; de Jesus Junqueira, J.R.; Corrêa, J.L.G. Food Drying Technologies and Their Contributions to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Food Res. Int. 2025, 222, 117651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mendonça, K.S.; Corrêa, J.L.G.; de Jesus Junqueira, J.R.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; Silveira, P.G.; Uemura, J.H.S. Peruvian Carrot Chips Obtained by Microwave and Microwave-Vacuum Drying. LWT 2023, 187, 115346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.U.; Corrêa, J.L.G.; Tanikawa, D.H.; Abrahão, F.R.; de Jesus Junqueira, J.R.; Jiménez, E.C. Hybrid Microwave-Hot Air Drying of the Osmotically Treated Carrots. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 156, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfiya, D.S.A.; Prashob, K.; Murali, S.; Alfiya, P.V.; Samuel, M.P.; Pandiselvam, R. Drying Kinetics of Food Materials in Infrared Radiation Drying: A Review. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-935584-87-5. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz. Métodos Físico-Químicos para Análise de Alimentos, 4th ed.; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, A.C.R.; Silva, L.S.; Oliveira, G.L.S.; Vieira, A.C.A.; Silvaa, G.F.; Ruzene, D.S.; Silva, D.P.; Pagani, A.A.C. Evaluation of the Viability of Probiotic Microorganisms in Microcapsules with Passion Fruit Pulp Resulting from the Ionic Gelation Process. Food Sci. Nutr. Technol. 2021, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, H.; Midilli, A.; Kilic, A.; Dincer, I. A Review on Thin-Layer Drying-Curve Equations. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, T.; Naik, H.R.; Hussain, S.Z.; Bhat, T.A.; Naseer, B.; Zargar, I.; Beigh, M.A. Impact of Spray Drying Conditions on the Reconstitution, Efficiency and Flow Properties of Spray Dried Apple Powder-Optimization, Sensorial and Rheological Assessment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinapong, N.; Suphantharika, M.; Jamnong, P. Production of Instant Soymilk Powders by Ultrafiltration, Spray Drying and Fluidized Bed Agglomeration. J. Food Eng. 2008, 84, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.L.; Sulaiman, R. Development of Beetroot (Beta Vulgaris) Powder Using Foam Mat Drying. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 88, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokapandian, S.; Venkatachalam, S.; Swamy, G.J.; Kuppusamy, K. Optimization of Foaming Properties and Foam Mat Drying of Muskmelon Using Soy Protein. J. Food Process Eng. 2016, 39, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, G.R.; Ghobadian, B. Effect of Spray-Drying Conditions on Physical Properties of Orange Juice Powder. Dry. Technol. 2005, 23, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, A. True, Particle, and Bulk Density of Shrinkable Biomaterials: Evaluation from Drying Experiments True, Particle, and Bulk Density of Shrinkable Biomaterials: Evaluation from Drying Experiments. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparino, O.A.; Tang, J.; Nindo, C.I.; Sablani, S.S.; Powers, J.R.; Fellman, J.K. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical Properties and Microstructures of Mango (Philippine “Carabao” Var.) Powder. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelen, S. Effect of Microwave Drying on the Drying Characteristics, Color, Microstructure, and Thermal Properties of Trabzon persimmon. Foods 2019, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.D.A.; Maciel, M.I.S.; De Lima, V.L.A.G.; Do Nascimento, R.J. Capacidade Antioxidante de Frutas. Rev. Bras. De Cienc. Farm. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 44, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, R.; Malta, L.G.; Carrasco, L.C.; Holanda, R.B.; Sousa, C.A.S.; Pastore, G.M. Atividade Antioxidante de Frutas Do Cerrado. Ciência E Tecnol. de Aliment. 2007, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Kunwar, M.; Kunwar, A.; Pokharel, P. Encapsulation of Extracted Oil from Mentha piperita in Alginate Beads. Biol. Med. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2025, 14, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.F.C.e.; da Silva Carvalho, A.G.; Rabelo, R.S.; Hubinger, M.D. Sacha Inchi Oil Encapsulation: Emulsion and Alginate Beads Characterization. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 116, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, M.; Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Fatemi, H.; Chen, G. Impact of Different Drying Methods on the Drying Time, Energy, and Quality of Green Peas. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Kaveh, M.; Fatemi, H.; Hernández-Hernández, J.L.; Fuentes-Penna, A.; Hernández-Hernández, M. Evaluation of the Changes in Thermal, Qualitative, and Antioxidant Properties of Terebinth (Pistacia atlantica) Fruit under Different Drying Methods. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, O.; Seyhun Kipcak, A.; Doymaz, I. Drying of Okra by Different Drying Methods: Comparison of Drying Time, Product Color Quality, Energy Consumption and Rehydration. Athens J. Sci. 2019, 6, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahbani, A.; Fakhfakh, N.; Balti, M.A.; Mabrouk, M.; El-Hatmi, H.; Zouari, N.; Kechaou, N. Microwave Drying Effects on Drying Kinetics, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Green Peas (Pisum sativum L.). Food Biosci. 2018, 25, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mesery, H.S.; Elabd, M.A. Effect of Microwave, Infrared, and Convection Hot-Air on Drying Kinetics and Quality Properties of Okra Pods. Int. J. Food Eng. 2021, 17, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, A.; Qin, L.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, Y. Comprehensive Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Activity of B. Subtilis-Fermented Polished Adlay Subjected to Different Drying Methods. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2124–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevali, A.; Minaei, S.; Khoshtagaza, M.H. Evaluation of Energy Consumption in Different Drying Methods. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelen, S.; Aktaş, T.; Karabeyoğlu, S.S.; Akyildiz, A. Drying Behavior of Prina (Crude Olive Cake) Using Different Types of Dryers. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Mesery, H.S.; Sarpong, F.; Xu, W.; Elabd, M.A. Design of Low-Energy Consumption Hybrid Dryer: A Case Study of Garlic (Allium sativum) Drying Process. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 33, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Quiroga, E.; Prosapio, V.; Fryer, P.J.; Norton, I.T.; Bakalis, S. Model Discrimination for Drying and Rehydration Kinetics of Freeze-Dried Tomatoes. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.A.; Jeremiah, O.A.; Bazambo, I.O.; Adetoro, O.B.; Mustapha, K.O.; Onyeka, C.F.; Ayorinde, T.A.; Abioye, A.O. Modelling the Influence of Hot Air on the Drying Kinetics of Turmeric Slices. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 13, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, A.H.; Hamzani, S.H.; Amirnordin, S.H.; Batcha, M.F.M.; Wahidon, R.; Wae-hayee, M. Drying Studies of Oil Palm Decanter Cake for Production of Green Fertilizer. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2022, 97, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yu, W.; Boiarkina, I.; Depree, N.; Young, B.R. Effects of Morphology on the Dispersibility of Instant Whole Milk Powder. J. Food Eng. 2020, 276, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kak, A.; Parhi, A.; Rasco, B.A.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Improving the Oxygen Barrier of Microcapsules Using Cellulose Nanofibres. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4258–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Nanda, S.K.; Yadav, D.N. Shelf-Life Study of Spray-Dried Groundnut Milk Powder. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.C.; Tan, C.P.; Nyam, K.L. Microencapsulation of Refined Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) Seed Oil by Spray Drying Using β-Cyclodextrin/Gum Arabic/Sodium Caseinate. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catelam, K.T.; Trindade, C.S.F.; Romero, J.T. Water Adsorption Isotherms and Isosteric Sorption Heat of Spray-Dried and Freeze-Dried Dehydrated Passion Fruit Pulp with Additives and Skimmed Milk [Isotermas de Adsorção e Calor Isostérico de Sorção de Polpa de Maracujá Desidratada Por Spray Dryer e Lio]. Cienc. E Agrotecnol. 2011, 35, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timaná, R.; Arango, O.; Osorio, O.; Benavides, O. Effect of Different Drying Methods on the Physicochemical Characteristics and Volatile Compound Profile of Pleurotus Ostreatus. Eng. Agric. 2024, 44, e20240026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuen, G.W.; Yi, L.Y.; Ying, T.S.; Von Yu, G.C.; Binti Yusof, Y.A.; Phing, P.L. Effects of Drying Methods on the Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Capacity of Kuini Powder. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2021, 24, e2020086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros Fernandes, R.V.; Borges, S.V.; Botrel, D.A. Influence of Spray Drying Operating Conditions on Microencapsulated Rosemary Essential Oil Properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhidajah; Pranata, B.; Yusuf, M.; Sya’di, Y.K.; Yonata, D. Microencapsulation of Umami Flavor Enhancer from Indonesian Waters Brown Seaweed. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 10, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Wagh, P.; Naik, J. Solvent Evaporation and Spray Drying Technique for Micro- and Nanospheres/Particles Preparation: A Review. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarry, I.E.; Ding, D.; Cai, T.; Wu, Z.; Huang, P.; Kan, J.; Chen, K. Inulin–Whey Protein as Efficient Vehicle Carrier System for Chlorophyll: Optimization, Characterization, and Functional Food Application. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 3445–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, W.D.R.; Nurbaya, S.R.; Murtini, E.S. Microencapsulation of Betacyanin Extract from Red Dragon Fruit Peel. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 9, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Influência Da Temperatura Do Ar de Secagem e Da Concentração de Agente Carreador Sobre as Propriedades Físico-Químicas Do Suco de Açaí Em Pó. Ciência E Tecnol. de Aliment. 2009, 29, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhalakshmy, S.; Don Bosco, S.J.; Francis, S.; Sabeena, M. Effect of Inlet Temperature on Physicochemical Properties of Spray-Dried Jamun Fruit Juice Powder. Powder Technol. 2015, 274, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajac, J.; Nikolovski, B.; Lončarević, I.; Petrović, J.; Bajac, B.; Đurović, S.; Petrović, L. Microencapsulation of Juniper Berry Essential Oil (Juniperus communis L.) by Spray Drying: Microcapsule Characterization and Release Kinetics of the Oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 125, 107430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan Dincer, E.; Temiz, H. Investigation of Physicochemical, Microstructure and Antioxidant Properties of Firethorn (Pyracantha coccinea Var. lalandi) Microcapsules Produced by Spray-Dried and Freeze-Dried Methods. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 155, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2013, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendoza Borges, P.H.; dos Reis, G.A.; de Mendoza Morais, P.H.; de Mendoza Morais, P.H.; de Moraes, B.A. Automação de Baixo Custo Na Colorimetria de Frutas/Low-Cost Automation in Fruit Colorimetry. Braz. Appl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 6, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitha, E.Z.M.; Araújo, A.B.S.; da Silva Machado, P.; de Siqueira Elias, H.H.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; de Barros Vilas Boas, E.V. Impact of Processing and Packages on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Mangaba Jelly. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e28221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.; Freitas, L.D.S.; Muniz, E.N.; Santana, J.G.S.; Da Silva, A.V.C. Phytochemical and Antioxidant Composition in Accessions of the Mangaba Active Germplasm Bank. Rev. Caatinga 2021, 34, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakulnarmrat, K.; Kittichonthawat, S. Encapsulation of Schleichera Oleosa Juice in Maltodextrin-Inulin and Maltodextrin-Gum Arabic Matrices: Drying Method Effects on Stability, Phenolic Bioaccessibility, and Antioxidant Delivery. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.S.; Chaves-Filho, A.B.; Silva, L.A.S.; Garcia, C.A.B.; Silva, A.R.S.T.; Dolabella, S.S.; da Costa, S.S.L.; Miyamoto, S.; Matos, H.R. Bioactive Compounds and Hepatoprotective Effect of Hancornia speciosa Gomes Fruit Juice on Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity In Vivo. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 2565–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriwidodo, S.; Pratama, R.; Umar, A.K.; Chaerunisa, A.Y.; Ambarwati, A.T.; Wathoni, N. Preparation of Mangosteen Peel Extract Microcapsules by Fluidized Bed Spray-Drying for Tableting: Improving the Solubility and Antioxidant Stability. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, J.P.; Azevedo, L.; de Souza, N.J.; Nunes, E.E.; de Vilas Boas, E.V.B. First Evaluation of the Antimutagenic Effect of Mangaba Fruit in Vivo and Its Phenolic Profile Identification. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Chacón, J.M.; Rodríguez-Pulido, F.J.; Heredia, F.J.; González-Miret, M.L.; Osorio, C. Characterization and Bioaccessibility Assessment of Bioactive Compounds from Camu-Camu (Myrciaria dubia) Powders and Their Food Applications. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera-Chávez, S.L.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Meza-Márquez, O.G.; Osorio-Revilla, G. Spray Drying and Spout-Fluid Bed Drying Microencapsulation of Mexican Plum Fruit (Spondias purpurea L.) Extract and Its Effect on In Vitro Gastrointestinal Bioaccessibility. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiza Koop, B.; da Silva, M.N.; da Silva, F.D.; Lima, K.T.D.S.; Soares, L.S.; de Andrade, C.J.; Valencia, G.A.; Monteiro, A.R. Flavonoids, Anthocyanins, Betalains, Curcumin, and Carotenoids: Sources, Classification and Enhanced Stabilization by Encapsulation and Adsorption. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Mean ± Standard Deviation [g/100 g] |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 85.18 ± 0.87 |

| Lipid | 1.05 ± 0.01 |

| Protein | 1.81 ± 0.02 |

| Ash | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| Crude Fiber | 5.10 ± 0.32 |

| Carbohydrate | 6.45 ± 0.45 |

| Model | Drying Treatment | k | a | b | R2 | χ2 | RMSE | SSE | MPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newton | CD | 1.98 × 10−4 | - | - | 0.7160 | 3.52 × 10−2 | 1.83 × 10−1 | 6.69 × 10−1 | 68.14 |

| MWD | 8.64 × 10−4 | - | - | 0.8017 | 3.04 × 10−2 | 1.59 × 10−1 | 1.52 × 10−1 | 14.75 | |

| IRD | 8.11 × 10−5 | - | - | 0.7140 | 2.82 × 10−2 | 1.66 × 10−1 | 1.21 × 10−0 | 112.99 | |

| Page | CD | 0.0 | 1.8781 | - | 0.9054 | 1.64 × 10−4 | 1.64 × 10−4 | 2.23 × 10−1 | 42.36 |

| MWD | 0.0 | 2.3503 | - | 0.9802 | 1.64 × 10−4 | 1.06 × 10−1 | 1.52 × 10−2 | 3.10 | |

| IRD | 0.0 | 3.5274 | - | 0.9851 | 1.64 × 10−4 | 5.03 × 10−2 | 6.88 × 10−2 | 21.83 | |

| Page modified | CD | 1.03 × 10−4 | 3.6400 | - | 0.9885 | 1.50 × 10−3 | 3.95 × 10−2 | 2.70 × 10−2 | 8.81 |

| MWD | 9.41 × 10−4 | 2.8392 | - | 0.9869 | 2.49 × 10−3 | 3.68 × 10−2 | 9.98 × 10−3 | 4.22 | |

| IRD | 2.42 × 10−4 | 3.5268 | - | 0.9851 | 1.64 × 10−3 | 4.08 × 10−2 | 6.88 × 10−2 | 21.84 | |

| Henderson and Pabis | CD | 1.06 × 10−4 | 1.2015 | - | 0.7791 | 2.89 × 10−2 | 1.61 × 10−1 | 5.21 × 10−1 | 59.80 |

| MWD | 9.86 × 10−4 | 1.1210 | - | 0.8291 | 3.28 × 10−2 | 1.48 × 10−1 | 1.31 × 10−1 | 14.38 | |

| IRD | 2.53 × 10−4 | 1.2086 | - | 0.7829 | 2.38 × 10−2 | 1.51 × 10−1 | 1.00 × 10−0 | 98.22 | |

| Wang-Singh | CD | - | 3.12 × 10−5 | 0.0 | 0.9870 | 4.16 × 10−4 | 1.67 × 10−2 | 3.06 × 10−2 | 10.57 |

| MWD | - | −1.87 × 10−4 | 0.0 | 0.9954 | 1.70 × 10−3 | 3.91 × 10−2 | 1.66 × 10−3 | 2.52 | |

| IRD | - | 7.06 × 10−5 | 0.0 | 0.9978 | 5.01 × 10−4 | 2.19 × 10−2 | 2.10 × 10−2 | 9.38 | |

| Diffusion Approach | CD | 0.0003 | −20.7729 | 0.9316 | 0.9008 | 1.15 × 10−2 | 1.03 × 10−1 | 2.34 × 10−1 | 40.02 |

| MWD | 0.0025 | −21.0037 | 0.9340 | 0.9416 | 1.49 × 10−2 | 8.64 × 10−2 | 4.47 × 10−2 | 5.93 | |

| IRD | 0.0006 | −10.4817 | 0.8747 | 0.8990 | 1.14 × 10−2 | 1.08 × 10−1 | 4.67 × 10−1 | 69.22 |

| Treatment | Dispersibility [%] | Wettability [s] | Hygroscopicity [% d.b.] | WAI [-] | Bulk Density [g/cm3] | Particle Density [g/cm3] | Porosity [-] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 248.4 ± 7.2 a | 87.0 ± 6.5 b | 398.7 ± 16.3 a | 2.57 ± 0.04 a | 0.296 ± 0.01 b | 0.927 ± 0.15 b | 0.674 ± 0.01 b |

| MWD | 121.7 ± 6.7 c | 115.3 ± 6.3 a | 380.8 ± 2.3 a | 1.78 ± 0.03 c | 0.303 ± 0.01 b | 0.945 ± 0.05 b | 0.677 ± 0.01 b |

| IRD | 163.7 ± 5.5 b | 43.3 ± 3.8 c | 203.1 ± 6.3 b | 2.01 ± 0.01 b | 0.382 ± 0.01 a | 1.339 ± 0.21 a | 0.732 ± 0.01 a |

| L* | a* | b* | ΔE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 42.27 ± 0.78 a | 6.64 ± 0.90 a | 9.08 ± 0.24 a | 11.27 |

| MWD | 41.45 ± 1.63 a | 4.79 ± 1.01 ab | 6.22 ± 0.88 b | 13.92 |

| IRD | 40.72 ± 2.46 a | 3.91 ± 0.04 b | 5.30 ± 0.19 b | 15.08 |

| Phenolic Compounds (mg EAG/100 g) | Antioxidant Activity (IC50) (μg/mL) | Ascorbic Acid (mg/100 g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh pulp | 4.62 ± 0.16 a | 225.30 ± 41.55 b | 1.16 ± 0.23 a |

| CD | 1.80 ± 0.06 c | 489.36 ± 78.29 a | 1.40 ± 0.40 a |

| MWD | 2.69 ± 0.64 b | 623.41 ± 55.87 a | 1.96 ± 0.35 a |

| IRD | 1.67 ± 0.05 c | 701.16 ± 152.72 a | 1.64 ± 0.23 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Uemura, J.H.S.; Junqueira, J.R.d.J.; Theodoro, Â.C.C.; Corrêa, J.L.G.; Balbinoti, T.C.V.; Carmo, J.R.d. Drying Methods Applied to Ionic Gelation of Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa) Pulp Microcapsules. ChemEngineering 2026, 10, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010012

Uemura JHS, Junqueira JRdJ, Theodoro ÂCC, Corrêa JLG, Balbinoti TCV, Carmo JRd. Drying Methods Applied to Ionic Gelation of Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa) Pulp Microcapsules. ChemEngineering. 2026; 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleUemura, Jordan Heiki Santos, João Renato de Jesus Junqueira, Ângela Christina Conte Theodoro, Jefferson Luiz Gomes Corrêa, Thaisa Carvalho Volpe Balbinoti, and Juliana Rodrigues do Carmo. 2026. "Drying Methods Applied to Ionic Gelation of Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa) Pulp Microcapsules" ChemEngineering 10, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010012

APA StyleUemura, J. H. S., Junqueira, J. R. d. J., Theodoro, Â. C. C., Corrêa, J. L. G., Balbinoti, T. C. V., & Carmo, J. R. d. (2026). Drying Methods Applied to Ionic Gelation of Mangaba (Hancornia speciosa) Pulp Microcapsules. ChemEngineering, 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering10010012