Synergistic Integration of ESG Across Life Essentials: A Comparative Study of Clothing, Energy, and Transportation Industries Using CEPAR® Methodology

Abstract

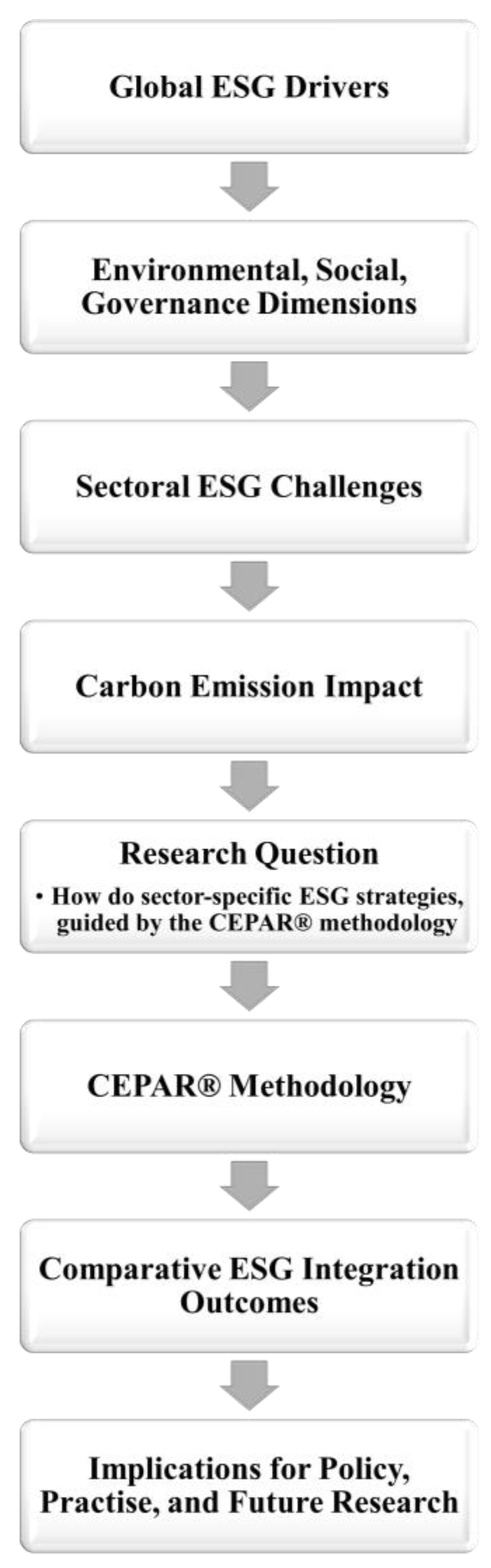

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Evolution of ESG

2.2. CEPAR® Methodology

- Challenge: identifying and defining ESG-related issues and opportunities.

- Evaluation: evaluating the materiality and impact of identified challenges.

- Planning: developing strategies and action plans to address ESG issues.

- Action: implementing planned strategies and monitoring progress.

- Review: reflecting on outcomes and identifying areas for improvement.

2.3. Theoretical Underpinnings

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection

- Company reports, including sustainability, annual, and other publicly available corporate documents;

- Corporate websites, including information from official company websites, press releases, and policy statements;

- Third-party ESG ratings based on reports from ESG rating agencies to provide an external perspective on the ESG performance of the companies under study;

- News articles and industry reports, media coverage, and industry analyses to provide context and identify any controversies or notable ESG-related events.

3.3. Data Analysis

- The ESG challenges that the company faced (Challenge phase);

- Evaluation and prioritization of the ESG challenges (Evaluation phase);

- Formulation and planning of strategies to address ESG issues (Planning phase);

- Implementation and action plans to address ESG issues (Action phase);

- Review and adjustment of the ESG approach (Review phase).

3.4. Limitations

4. Case Study: H&M Group

4.1. Company Overview

4.2. CEPAR® Analysis: H&M

4.2.1. Challenges

4.2.2. Evaluation

4.2.3. Planning

4.2.4. Action

- Partner with renewable energy providers to achieve 100% renewable energy in its supply chain by 2030;

- Launch consumer education campaigns on garment recycling and incentivizing participation;

- Invest in research and development (R&D) for innovative materials use and the realization of waterless dyeing technologies.

- Conduct annual third-party supplier audits and publish the results;

- Implement training programs to improve labor conditions and fair wage compliance;

- Expand H&M Foundation initiatives in education and healthcare and implement employee training programs focused on renewable energy and greenhouse gas reduction;

- Ensure that employees are equipped with the skills necessary to support sustainability effort;

- Increase transparency by publicly disclosing sustainability efforts, supply chain practices, and labor standards to its stakeholders, such as publishing annual sustainability reports and sharing supplier lists to keep shareholders informed;

- Engage with worker rights organizations, NGOs, and industry associations to gain insights and co-develop solutions by participating in multi-stakeholder initiatives to address ESG risks.

- Include publishing a road map to address greenwashing allegations and improving transparency;

- Establish a stakeholder advisory board to provide ESG strategy input;

- Join industry coalitions, such as the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, to advocate for standardized reporting;

- Collaborate with suppliers to improve labor conditions and promote responsible sourcing through capacity-building programs and training initiatives;

- Establish rigorous auditing processes to evaluate the work conditions, labor standards, and environmental practices of suppliers, including regular inspections and independent third-party audits.

4.2.5. Review

- Track its progress toward the 2030 material goals and measure the impact of its circular fashion initiatives.

- Establish Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and define specific KPIs to measure its progress toward its ESG objectives, thus ensuring that these metrics are aligned with its overall sustainability goals.

- Monitor labor conditions through audits and worker feedback surveys and evaluate diversity and inclusion programs by using representation metrics and employee satisfaction data.

- Conduct biannual audits to identify areas for improvement and ensure compliance with ESG standards and regulations, thereby reinforcing its commitment to responsible practices.

- Regularly communicate its performance to its stakeholders, which facilitates transparency and keeps all parties informed of the progress and challenges.

- Evaluate its sustainability report credibility through third-party verification and stakeholder feedback;

- Review the performance of the Sustainability Committee and stakeholder advisory board by engaging both internal and external stakeholders in the review process to promote accountability and transparency. This involvement can provide diverse perspectives and insights.

- Insights gained from the review phase should guide future decision-making processes, thus enabling H&M to continuously enhance its ESG practices and adapt to evolving challenges and opportunities.

5. Case Study: Hong Kong and China Gas Company Limited (Towngas)

5.1. Energy Sector Overview

5.2. CEPAR® Analysis: Towngas

5.2.1. Challenges

5.2.2. Evaluation

5.2.3. Planning

- Lowering its carbon intensity;

- Developing hydrogen technology;

- Integrating renewable energy sources, expanding the hydrogen market, and promoting energy efficiency technologies;

- Setting KPIs;

- Integrating renewable energy sources and contributing to SDGs.

5.2.4. Action

5.2.5. Review

6. Case Study: MTR Corporation Limited

6.1. Context of ESG in Transportation Industry

6.1.1. Environmental Trends

6.1.2. Social Trends

6.1.3. Governance Trends

6.2. CEPAR® Analysis

6.2.1. Challenge

6.2.2. Evaluation

6.2.3. Planning

- Providing eco-friendly services while contributing to economic growth as per SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, based on its Environmental and Social Responsibility Policy;

- Prioritizing accessibility for all by focusing on universal mobility and diversity as per SDG 10: Reduce Inequalities, as found in its Sustainability Report, which highlights efforts to design accessible stations and promote gender diversity on the board;

- Focusing on reducing GGEs through sustainable practices, as per SDG 13: Climate Action, based on its commitment to emissions reduction as outlined in its Sustainability Report.

6.2.4. Action

- Investing in renewable energy sources to lower carbon emissions;

- Enhancing diversity and inclusion programs for employees;

- Strengthening governance practices to ensure accountability;

- Promoting transparency through regular reporting.

6.2.5. Review

7. Comparative Discussion

7.1. Challenge Phase

- The environmental challenges of H&M are largely tied to its supply chain and product life cycle, including resource consumption in production and waste generation from fast fashion.

- Towngas focuses on the environmental impact of energy production and distribution, particularly carbon emissions and air quality.

- The environmental challenges of the MTR center on the energy efficiency of its transport operations and the sustainability of its property developments.

- H&M emphasizes worker safety and fair labor practices in its supply chain.

- Towngas focuses on customer safety in gas usage and occupational safety for its employees.

- MTR prioritizes passenger safety in its railway operations.

7.2. Evaluation Phase

- The material issues of H&M are heavily focused on supply chain management, circular economy, and ethical fashion.

- Towngas prioritizes issues related to energy transition, air quality, and community engagement.

- The material issues of the MTR center on transport safety, service reliability, and sustainable urban development.

7.3. Planning Phase

- The strategy of H&M is notably ambitious, with the aim to achieve industry leadership in sustainable fashion.

- Towngas adopts a strategy that focuses on balancing the transition to cleaner energy along with maintaining a reliable and affordable supply of energy.

- The MTR uses a strategy that emphasizes the integration of sustainable practices in both its transport and property development businesses.

7.4. Action Phase

- H&M has implemented a wide range of initiatives across its value chain, from sustainable sourcing to garment recycling programs.

- Towngas has focused on technological innovations for cleaner energy production and distribution.

- MTR has implemented actions to improve the energy efficiency of its railway operations and the sustainability of its property developments.

7.5. Review Phase

7.6. Overall ESG Integration

- H&M shows the most comprehensive integration of ESG considerations across its business model, possibly due to the high visibility and scrutiny of the environmental and social impacts of the fashion industry.

- The integration of ESG by Towngas is very much focused on the environmental aspect, particularly related to energy transition and emissions reduction.

- The integration of ESG by the MTR is well-balanced across the ESG aspects, thus reflecting its role as both a transport provider and property developer.

7.7. ESG Strategy Limitations in China’s Institutional Context

7.8. ESG and Financial Outcomes: Connecting Strategy with Results

8. Conclusions

8.1. Key Findings

8.2. Implications for Practice

8.3. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Global Compact. Who Cares Wins. Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World; United Nations Global Compact: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Eccles, R.G.; Lee, L.-E.; Stroehle, J.C. The Social Origins of ESG: An Analysis of Innovest and KLD. Organ. Environ. 2019, 33, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. The Use of ESG Scores in Academic Literature: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Enterprise. Communities 2023, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.P.Y.; Hui, M.S.F.; Yip, A.W.H. The New Cepar® Model: A Five-Step Methodology to Tackle Corporate ESG Challenges. Public Adm. Policy 2024, 27, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, B.O.; Adebisi, A.O. Strategic Environmental Scanning and Organization Performance in a Competitive Business Environment. Econom. Insights-Trends Chall. 2012, LXIV, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. Strategic Planning. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1993, 36, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, P.; Brahmi, M.; Pallayil, B.; Mishra, B.R. Mediating Effects of Foreign Direct Investment Inflows on Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Economies 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ao, X.; Zhang, M.; Pu, M. ESG Performance and Carbon Emission Intensity: Examining The Role of Climate Policy Uncertainty and the Digital Economy in China’s Dual-Carbon Era. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 1526681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textile Exchange. Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report; Textile Exchange: Lamesa, TX, USA, 2023; Available online: https://textileexchange.org/knowledge-center/reports/materials-market-report-2023/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Drew, D.; Yehounme, G. The Apparel Industry’s Environmental Impact in 6 Graphics; World Resource Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pechacek, W. Unfair Labor Practices: Impact on Employees, Employers, and Society. J. Int. Acad. Case Stud. 2023, 29, 1–2. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/Unfair-labor-practices-impact-on-employees-employers-and-society-1532-5822-29-1-102.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustineri—The Role of Textile and Fashion Industries to Achieve SDG 12 & 15; United Nations—Department of Ecnomic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/sustineri-role-textile-and-fashion-industries-achieve-sdg-12-15 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Manohar, M. Track and Trace: Blockchain’s Supply Chain Superpower; Fobes Technology Council: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Consolidated Set of the GRI Standards; GRI Standards: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/download-the-standards (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Commission. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Tonti, L. Fashion Brands Grapple with Greenwashing: ‘It’s Not a Human Right to Say Something Is Sustainable’; The Guardian: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2022/nov/19/fashion-brands-grapple-with-greenwashing-its-not-a-human-right-to-say-something-is-sustainable (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Kering. 2020–2023 Progress Report; Kering: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.kering.com/en/sustainability/crafting-tomorrow-s-luxury/2017-2025-roadmap/2020-2023-progress-report (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Stella McCartney. Impact Report; Stella McCartney: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.stellamccartney.com/gb/en/sustainability/measuring-our-impact.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Nike, Inc. Sustainability. Move to Zero. Nike. Available online: https://www.nike.com/sustainability (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Rejda, G.E. Principles of Risk Management and Insurance, 6th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peliu, S.-A. Exploring the Impact of ESG Factors on Corporate Risk: Empirical Evidence for New York Stock Exchange Listed Companies. Futur. Bus. J. 2024, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffo, R.; Patalano, R. ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimsbach, D.; Hahn, R.; Gürtürk, A. Integrated Reporting and Assurance of Sustainability Information: An Experimental Study on Professional Investors’ Information Processing. Eur. Account. Rev. 2017, 27, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department. ESG Investing—Statistics & Facts; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7463/esg-and-impact-investing/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Key ESG. 50 Sustainability Statistics You Need to Know in 2025; Key ESG: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.keyesg.com/article/50-esg-statistics-you-need-to-know-in-2024 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- World Bank. Sovereign ESG Data Portal; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/esg (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Morningstar Sustainalytics. Sustainalytics—Company ESG Risk Ratings and Scores; Morningstar Sustainalytics: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.sustainalytics.com/esg-ratings (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- MSCI ESG Research LLC. MSCI ESG Ratings: Methodology and Definitions; MSCI ESG Research LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/34424357/MSCI+ESG+Ratings+Methodology.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Licari, J.; Loiseau-Aslanidi, O.; Piscaglia, S.; Solis Gonzalez, B. Moody’s Analytics. ESG Score Predictor: Applying Quantitative Approach for Expanding Company Coverage; Moody’s Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- H&M Group. H&M Group Annual & Sustainability Report 2024; H&M Group: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://hmgroup.com/investors/annual-and-sustainability-report (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Sustainability Resource Directory—Circular Fashion Initiatives; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/fashion/overview (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- H&M Group. Climate Transition Plan; H&M Group: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Climate-Transition-Plan.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- van Daalen, E.; Mabillard, N. Human Rights in Translation: Bolivia’s Law 548, Working Children’s Movements, and the Global Child Labour Regime. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2018, 23, 596–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Matin, S.; Mahmud, A.; Kibria, B.G. A Study on Present Scenario of Child Labour in Bangladesh. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man Hin, E.C.; Hiu, F.C.; Yui Yip, J.L.; Wai Ying, L.L.; Chi Kuen, D.H. Rebuilding a More Sustainable Fashion Industry After COVID-19. HSUHK Bus. Rev. 2022, 4, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, S.A.; Moore, C.M. Diversity, Inclusivity and Equality in the Fashion Industry. In Pioneering New Perspectives in the Fashion Industry: Disruption, Diversity and Sustainable Innovation; Ritch, E.L., Canning, C., McColl, J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Business of Fashion. The Best of BoF 2023: Diversity’s Litmus Test; Business of Fashion: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.businessoffashion.com/tags/tag/best-of-bof (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Queensborough Community College. Definition for Diversity; Queensborough Community College: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dreska, H. The Impact of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Fashion Industry. Bachelor’s Thesis, Bryant University, Smithfield, RI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA); PVH Corp. State of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion in Fashion; PVH Corp.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pvh.com/news/press-releases/cfda-and-pvh-corp-release-state-of-diversity-equity--inclusion-in-fashion-report (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Ayala, J. Can Community Engagement Enhance Sustainable Fashion? The Fashion Connection: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- H&M Group. Community Engagement; H&M Group: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025; Available online: https://hmgroup.com/sustainability/fair-and-equal/community-engagement (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Sáenz, J.; Seuring, S. Traceability and Transparency for Sustainable Fashion-Apparel Supply Chains. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 26, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. Sustainability Reporting Standards; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Clifford Chance. Sustainability & ESG Trends 2025; Clifford Chance LLP: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.cliffordchance.com/content/dam/cliffordchance/briefings/2025/02/sustainability-and-esg-trends-2025-publication.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- ESG News. H&M Introduce Their Team of Sustainability Experts; ESG News: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://esgnews.com/hm-introduce-their-team-of-sustainability-experts (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Ho, D.C.K. A Case Study of H&M’s Strategy and Practices of Corporate Environmental Sustainability. In Logistics Operations, Supply Chain Management and Sustainability; Golinska, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Mahtab, K.; Joseph, S.; Shen, L. Blockchain Technology and its Relationships to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhizadeh, M.; Saberi, S.; Sarkis, J. Blockchain Technology and the Sustainable Supply Chain: Theoretically Exploring Adoption Barriers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VelaZquez, A. Questionpro. H&M Customer Experience: The Role of a CX Strategy; H&M Group: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khitous, F.; Urbinati, A.; Verleye, K. Product-Service Systems: A customer engagement perspective in the fashion industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokessa, M.; Marette, S. A Review of Eco-Labels and Their Economic Impact. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 13, 119–163. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dee9/451538398bcddefba9322d4ddc0119274daf.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- H&M Group. Materials; H&M Group: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Apparel Coalition. Collaborative Efforts in ESG; Sustainable Apparel Coalition: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://slconvergence.org/updates/sac-slcp-collaborative-work-to-transform-global-supply-chains (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Suen, D.W.-S.; Chan, E.M.-H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Lee, R.H.-P.; Tsang, P.W.-K.; Ouyang, S.; Tsang, C.-W. Sustainable Textile Raw Materials: Review on Bioprocessing of Textile Waste via Electrospinning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M. H&M Case Shows How Greenwashing Breaks Brand Promise; Forbes: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, M. H&M to Remove Sustainability Labels from Products Following Investigation by Regulator; ESG Today: Modi’in, Israel, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fashion Revolution. Fashion Transparency Index 2023; Fashion Revolution: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/fashion-transparency-index-2023 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Jestratijevic, I.; Uanhoro, J.O.; Creighton, R. To Disclose or not to Disclose? Fashion Brands’ Strategies for Transparency in Sustainability Reporting. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 26, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonti, L. Fashion Greenwashing Glossary: What Do ‘Circular’, ‘Sustainable’ and ‘Zero Waste’ Really Mean? The Guardian: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/apr/17/fashion-greenwashing-glossary-what-do-circular-sustainable-and-zero-waste-really-mean (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Lau, Y.-Y.; Ranjith, P.V.; Man Hin, C.E.; Kanrak, M.; Varma, A.J. A New Shape of The Supply Chain During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Foresight 2022, 25, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business of Fashion. Diversity and Inclusion in Fashion; Business of Fashion: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.businessoffashion.com/topics/workplace-talent/diversity-inclusion (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Commission. The EU’S New Digital Product Passport (DPP): Everything You Need to Know; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/en/news-events/news/eus-digital-product-passport-advancing-transparency-and-sustainability (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- ESG News. Ellen MacArthur Foundation Initiates Drive for Circular Business Models in Fashion Industry; ESG News: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Gaur, V.; Liu, J. Supply chain transparency and blockchain design. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 3245–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fang, Y.; Su, N. Shein: Ultra-Fast Fashion’s Esg Challenges; Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Labor Association. Annual Report on Fair Labor Practices; Fair Labor Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.fairlabor.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/FLA-annual-report.2023-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- The Hong Kong and China Gas Company Limited. Annual Report; The Hong Kong and China Gas Company Limited: Hong Kong, China, 2023; Available online: https://annualreports.ai/company/hong-kong/utility/hong-kong-china-gas (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Hawken, P.; Lovins, A.B.; Lovins, L.H. Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution, 1st ed.; Little, Brown and Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, H. The Rise in Investors’ Awareness of Climate Risks after The Paris Agreement and the Clean Energy-Oil-Technology Prices Nexus. Energy Econ. 2022, 106, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinks, A.; Scholtens, B.; Mulder, M.; Dam, L. Fossil Fuel Divestment and Portfolio Performance. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, E.; Kruit, K.; Teng, M.; Hesselink, F. The Natural Gas Phase-Out in the Netherlands; CE Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://cedelft.eu/publications/the-natural-gas-phase-out-in-the-netherlands (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- OECD. Revised Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/media-advisories/2024/10/revised-guidelines-on-corporate-governance-of-state-owned-enterprises-and-new-report-on-soe-ownership-and-governance.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- McKerracher, C. Electric Vehicle Outlook 2023; BloombergNEF: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://about.bnef.com/insights/clean-transport/electric-vehicle-outlook (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Peloton Technology. Platooning Technology White Paper; Peloton Technology: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.freightwaves.com/news/peloton-unveils-level-4-platooning-technology-with-autonomous-following-truck (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Wilson, A.; Mason, B. The coming disruption—The rise of mobility as a service and the implications for government. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS Foundation. IFRS S2 Climate-Related Disclosures; IFRS: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/ifrs-sustainability-standards-navigator/ifrs-s2-climate-related-disclosures (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- S&P Global Ratings. ESG in Credit Ratings; S&P Global: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research-insights/special-reports/esg-in-credit-ratings (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- MTR Corporation Limited. Sustainability Report 2024; MTR Corporation Limited: Hong Kong, China, 2023; Available online: https://www.mtr.com.hk/sustainability/en/home.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Yui, D.; Melim-McLeod, C. Environmental, Social and Governance in China: 2024 in Retrospect; University of Edinburgh—Business School: Edinburgh, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, K.; Ling, Y.; Cao, M. The Impacts of China’s Sustainable Financing Policy on Environmental, Social And Corporate Governance (ESG) Performance. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG International. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Unlock the Power of ESG to Transform Your Business; KPMG International: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/what-we-do/ESG.html (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Loew, E.; Endres, L.; Xu, Y. How ESG Performance Impacts a Company’s Profitability and Financial Performance. European Banking Institute Working Paper Series no. 162. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-S. The Impact of ESG Performance on the Financial Performance of Companies: Evidence From China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-Share Listed Companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1507151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Timo, B.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from more than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. A Comparative Study of Cultural Differences in ESG Reports of Sino-American Multinational Corporations. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.R. ESG’s Global Dissemination and Impact: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 120, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Saini, N.; Shri, C.; Bhatia, S. Cross-Country Comparative Trend Analysis In ESG Regulatory Framework Across Developed and Developing Nations. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2024, 35, 61–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Issue | Nature | Shareholders | Customers | Govt/NGO | Local Businesses | Local Community |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term goals | Reduce greenhouse gas emissions (climate impact) | Invest in renewable energy/low -carbon technology (financial) | Reduce greenhouse gas emissions (financial) | Reduce carbon emission (climate impact) | Renewable technology that would lower costs (financial) | Cleaner environment, fewer negative climate issues (climate/environmental impact) |

| Long-term goals | Eliminate carbon intensity (net-zero emission) technology (financial) | Invest in renewable energy/zero-carbon | Eliminate carbon intensity (net-zero emission) | Support H&M to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045 (net-zero emission) | Successful business (financial) | Investing in large-scale wind farm to enable the transformation of renewable energy market (climate/environmental impact and financial) |

| Positive impact | Meet carbon neutrality by 2045 (climate/environmental impact) | Enhance ESG performances of H&M (both climate/environmental impact and financial) | Enhance ESG performance (climate/environmental impact and financial) | Government devises policy to support companies to meet carbon neutrality by 2045 (financial) | Attract more customers who care about sustainability (financial) | Provides more job opportunities and economic growth: Investing in renewable energy/low-carbon technologies can stimulate local economic growth and create more new job opportunities (financial). |

| Negative impact | Carbon reduction technology may increase environmental burden, e.g., solar panel disposal, raw material depletion, wildlife interactions, land use, and habitat disruption, etc. (environmental impact) | Technological obsolescence: technology may become outdated or replaced in the future (financial) | Renewable energy /Greenhouse gas emission reduction technology imposes cost to customers (financial) | Enforce policy for companies to invest more to eliminate greenhouse gas emission, when companies may be struggling financially to completely eliminate their reliance on traditional energy/fuel use (environmental impact and financial) | Technological/ renewable energy innovation and competition: may result in pricing pressure, market share reduction, and need for companies to continuously innovate to stay ahead (financial) | Large-scale renewable energy projects may lead to opposition from local community due to concerns over land use (social) |

| Indicator | Value/Target | Source/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| % of sustainable or recycled materials | 85% in 2023; target: 100% by 2030 | H&M Sustainability Report 2024 |

| GHG emissions reduction (Scopes 1–3) | 22% reduction since 2019; target: 56% by 2030 | H&M Climate Transition Plan 2024 |

| Renewable energy use in operations | 95% in 2023; target: 100% by 2030 | H&M Group Annual Report 2024 |

| Water consumption reduction | 14% reduction from 2022 baseline | H&M Sustainability Metrics 2024 |

| Circular fashion participation (garment collection) | 20,000 tons collected globally in 2023 | Ellen MacArthur Foundation Circularity Report |

| Material Issue | Nature | Shareholders | Customers | Govt/NGO | Local Businesses | Local Community |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term goals | Reduce carbon intensity (environmental impact) | Invest in low-carbon technology (financial) | Reduce carbon intensity and more energy efficient (financial) | Reduce carbon intensity (environmental impact) | More energy-efficient technology to lower cost (financial) | Better environment, fewer adverse climate issues (environmental impact) |

| Long-term goals | Eliminate carbon intensity (net-zero emission) | Invest in zero-carbon technology (financial) | Eliminate carbon intensity (net-zero emission) | Support the company to reach carbon neutrality by 2050 (net-zero emission) | Successful business (financial) | Energy independence: enhanced by reducing reliance on fossil fuel imports, such as investing in large-scale solar panels to produce hydrogen (environmental impact and financial) |

| Positive impact | Meet carbon neutrality by 2050 (environmental impact) | Enhance ESG performances of companies (both environmental impact and financial) | Enhance ESG performances of themselves (both environmental impact and financial) | Govt may devise policy to help companies meet carbon neutrality by 2050 (financial) | Attract more customers (financial) | Job creation and economic growth: Investing in low-carbon technologies often stimulates local economic growth and creates new job opportunities (financial). |

| Negative impact | Carbon reduction technology may increase environmental burden, such as raw material depletion, solar panel disposal, wildlife interaction, land use, and habitat disruption, etc. (environmental impact) | Technological obsolescence: technology may become outdated or be replaced in the future (financial) | Carbon reduction technology may impose costs on customers (financial) | Force companies to invest more to eliminate carbon, while the companies may struggle financially to completely eliminate reliance on fossil fuels (environmental impact and financial). | Technological competition leads to pricing pressure, reduced market share, or the need for continuous innovations to stay ahead (financial). | Large-scale renewable energy projects may face opposition from local communities due to concerns over land use (social). |

| Indicator | Value/Target | Source/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Scope 1 emissions (customer combustion) | 1.49 million tonnes CO2 (2023) | Towngas Annual Report 2024 |

| Scope 1 emissions (production) | 0.34 million tonnes CO2 (2023) | Towngas Sustainability Report |

| Hydrogen content in gas mix | ~50% H2 in distributed gas | Towngas Technical Disclosure |

| Renewable energy integration (pilot) | Solar-powered hydrogen refueling stations | EcoCeres/Towngas Pilot Projects |

| Biofuel production (via EcoCeres) | 100,000+ tonnes of HVO/SAF annually | EcoCeres ESG Disclosure 2024 |

| Stakeholder | Customers | Employees | Investors | Regulators | Suppliers | Community | Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term goals | Reliable and efficient transportation services | Job security | Profitability | Compliance with regulations | Timely payments | Noise reduction | Biodiversity conservation |

| Comfortable and safe travel | Safe work conditions | Dividends | Safety standards | Fair procurement practices | Community engagement | Carbon reduction | |

| Long-term goals | Sustainable and resilient transport infrastructure | Career growth and development | Sustainable financial performance | Environmental stewardship | Long-term partnerships | Sustainable urban development | Ecological balance |

| Reduced environmental impact | Work–life balance | Long-term value creation | Community engagement | Sustainable supply chain | Reduced pollution | Climate resilience | |

| How company contributes to goals | MTR invests in energy-efficient trains and stations | MTR promotes employee well-being and safety | MTR’s commitment to ESG principles enhances investor confidence | MTR adheres to safety and environmental regulations | MTR supports local suppliers | MTR invests in noise barriers and green spaces. | MTR invests in green infrastructure |

| Provides reliable and timely services | Offers training and advancement opportunities | Strategic investments in sustainable projects | Participates in community consultations | Encourages ecofriendly sourcing | Participates in community events | Reduces carbon emissions through energy-efficient operations | |

| How company negatively impacts goals | Service disruptions due to maintenance or system failures | High-stress work environment | Financial losses due to operational inefficiencies | Regulatory fines for non-compliance | Unfair procurement practices affecting supplier viability | Construction disruptions affecting residents | Land use changes affecting natural habitats |

| Overcrowding during peak hours | Labor disputes affecting operations | Negative impact on reputation affecting stock value | Legal disputes affecting reputation | Supply chain disruptions | Environmental impact during expansion projects | Energy consumption during operations |

| Indicator | Value/Target | Source/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| GHG emissions per passenger-km | 28.5 g CO2/passenger-km (2023) | MTR Sustainability Report 2024 |

| Renewable electricity usage | 42% of total electricity (2023); target: 60% by 2030 | MTR Climate Strategy 2024 |

| Energy efficiency improvement | 12% reduction in energy use per train-km since 2018 | MTR Energy Audit 2024 |

| Accessibility compliance (stations) | 100% of stations barrier-free | MTR Annual Report 2024 |

| ESG risk rating (Sustainalytics) | 19.8 (Low Risk) | Sustainalytics ESG Risk Ratings 2024 |

| Company | Environmental Limitations | Social Limitations | Governance Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| H&M Group |

|

|

|

| Towngas |

|

|

|

| MTR Corporation |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, E.M.H.; Hui, F.W.-C.; Suen, D.W.-S.; Tsang, C.-W. Synergistic Integration of ESG Across Life Essentials: A Comparative Study of Clothing, Energy, and Transportation Industries Using CEPAR® Methodology. Standards 2025, 5, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030017

Chan EMH, Hui FW-C, Suen DW-S, Tsang C-W. Synergistic Integration of ESG Across Life Essentials: A Comparative Study of Clothing, Energy, and Transportation Industries Using CEPAR® Methodology. Standards. 2025; 5(3):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030017

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Eve Man Hin, Fanucci Wan-Ching Hui, Dawson Wai-Shun Suen, and Chi-Wing Tsang. 2025. "Synergistic Integration of ESG Across Life Essentials: A Comparative Study of Clothing, Energy, and Transportation Industries Using CEPAR® Methodology" Standards 5, no. 3: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030017

APA StyleChan, E. M. H., Hui, F. W.-C., Suen, D. W.-S., & Tsang, C.-W. (2025). Synergistic Integration of ESG Across Life Essentials: A Comparative Study of Clothing, Energy, and Transportation Industries Using CEPAR® Methodology. Standards, 5(3), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030017