Biological Stability and Microbial Recovery Responses in Vermicomposting of Chemically Intensive Tomato Residues: Defining Management Limits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Preparation

2.2. Experimental Strategy and Treatment Mixtures

2.3. Vermicomposting Setup and Process Maintenance

2.4. Experimental Design and Sampling Methodology

2.5. Chemical and Biological Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Earthworm Survival and Experimental Adjustment

3.2. Chemical Properties

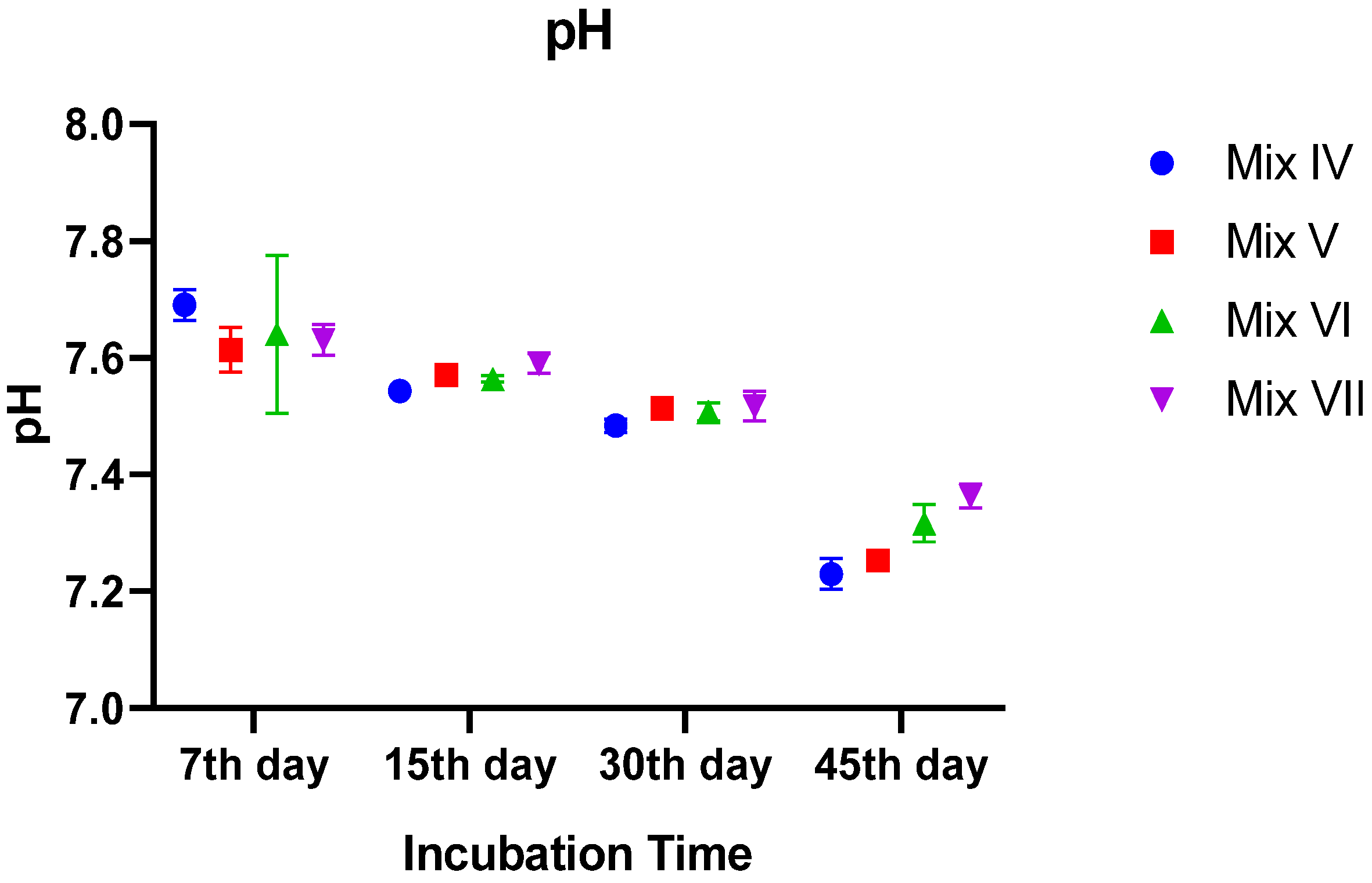

3.2.1. pH Dynamics

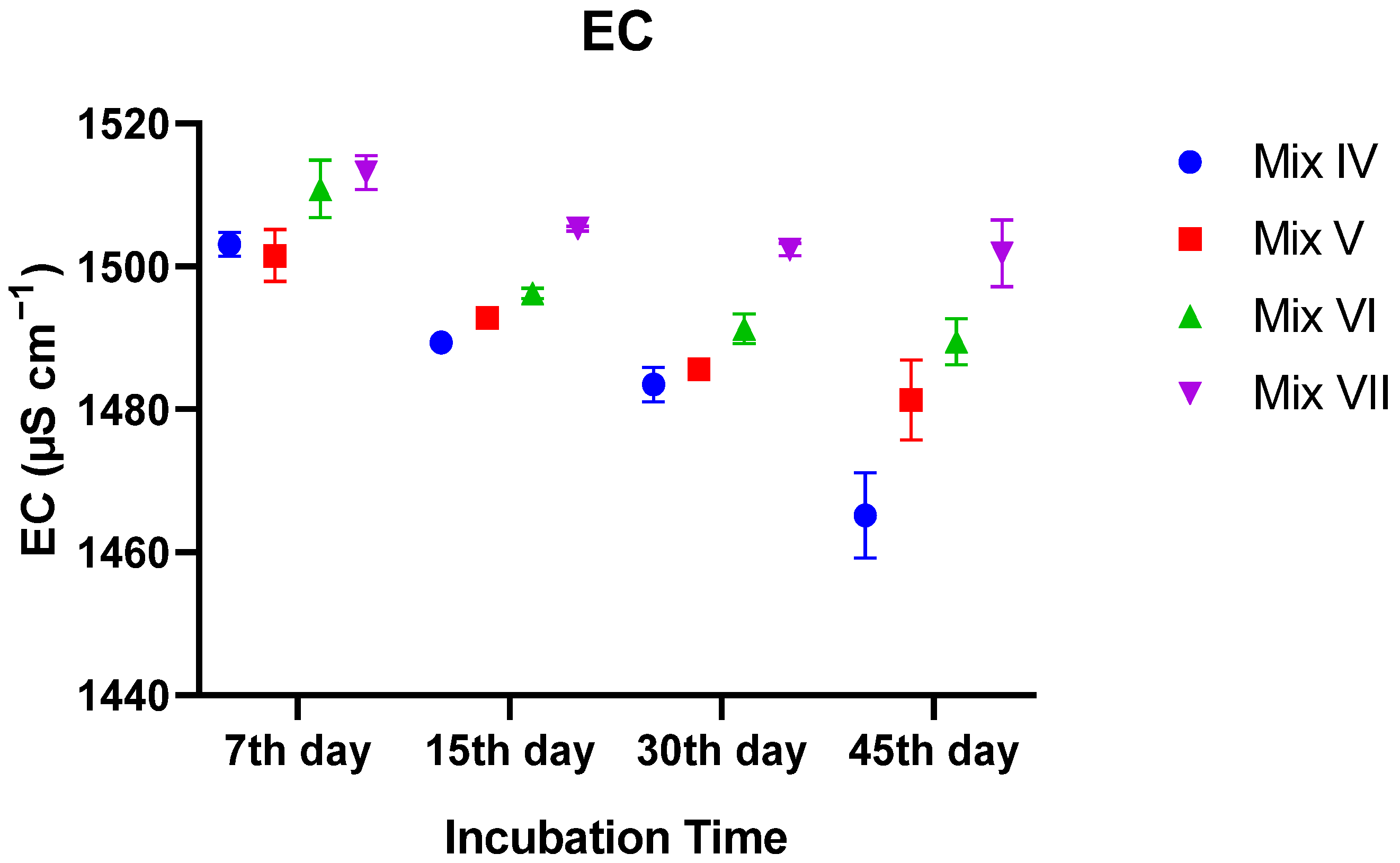

3.2.2. Electrical Conductivity (EC)

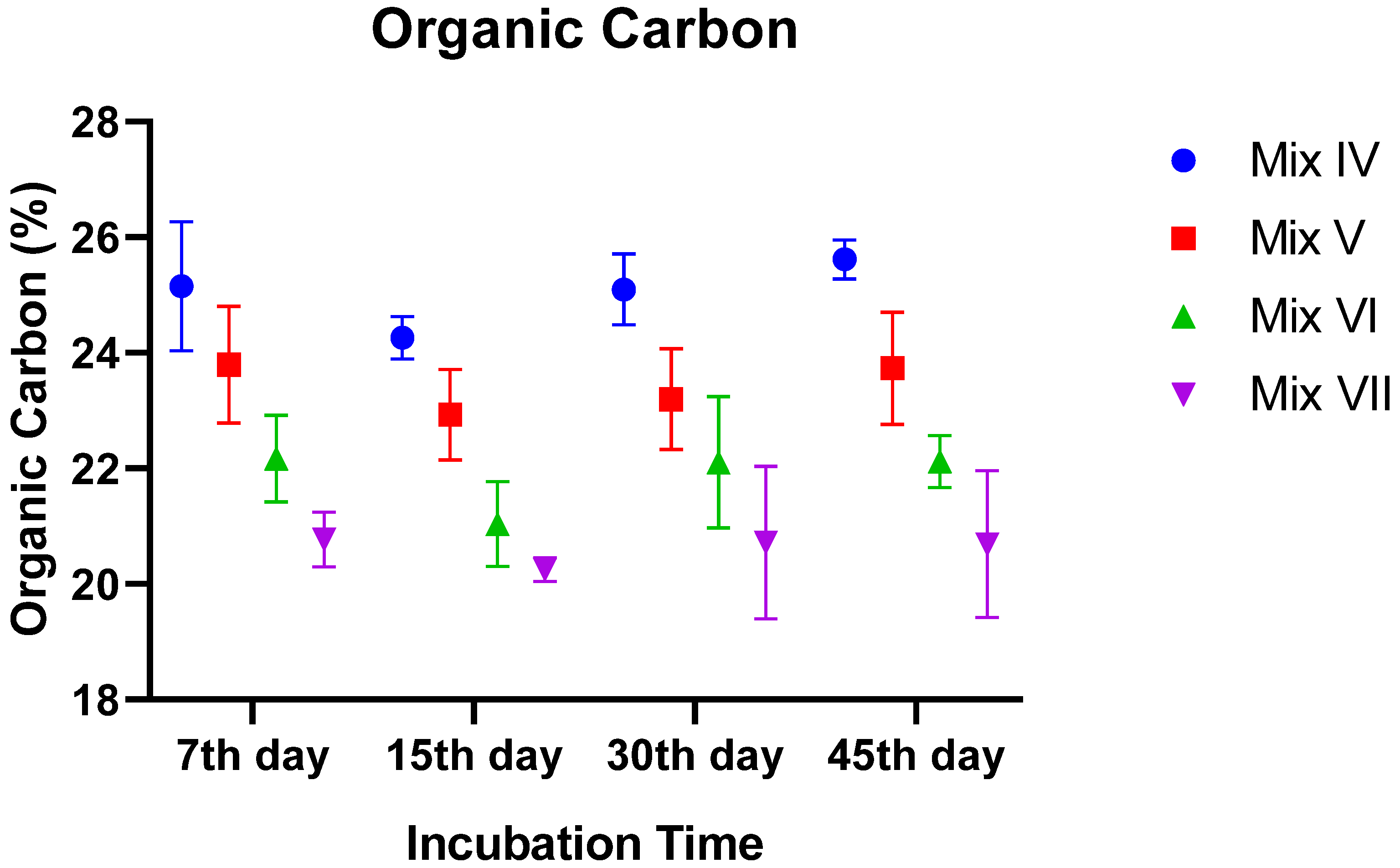

3.2.3. Organic Matter (OM) and Organic Carbon (OC)

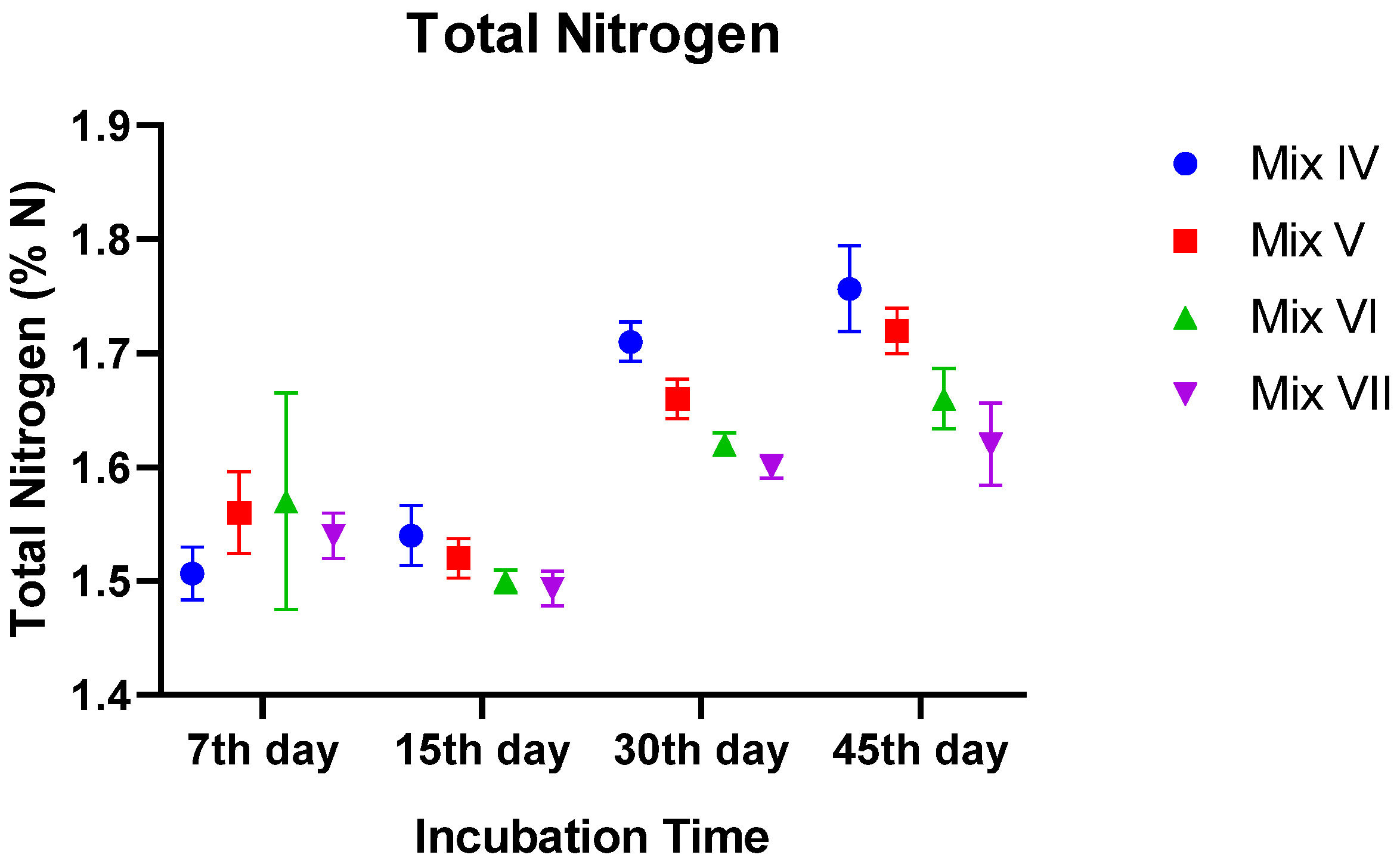

3.2.4. Total Nitrogen (TN)

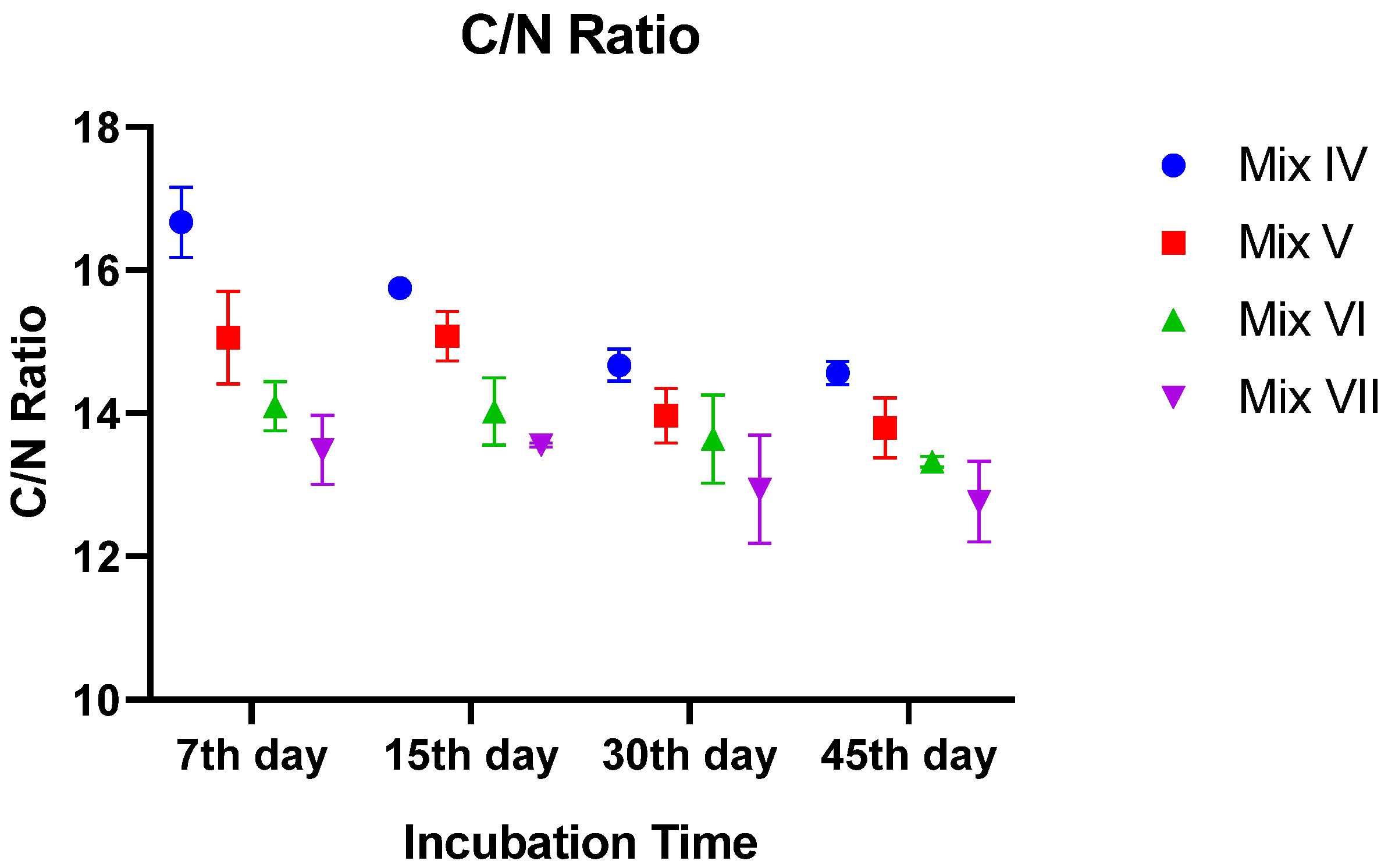

3.2.5. C/N Ratio

3.3. Biological Activity

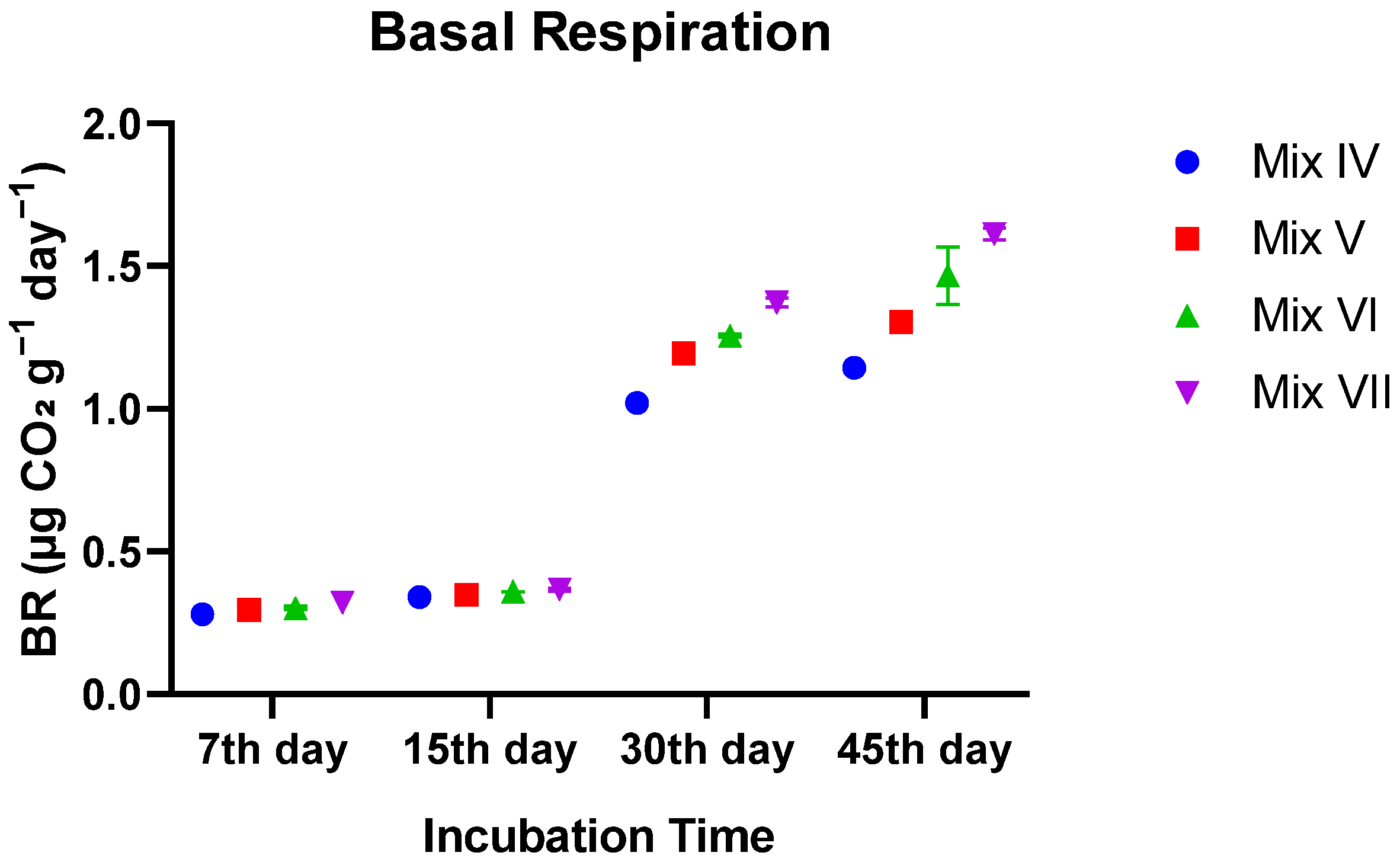

3.3.1. Basal Respiration (BR)

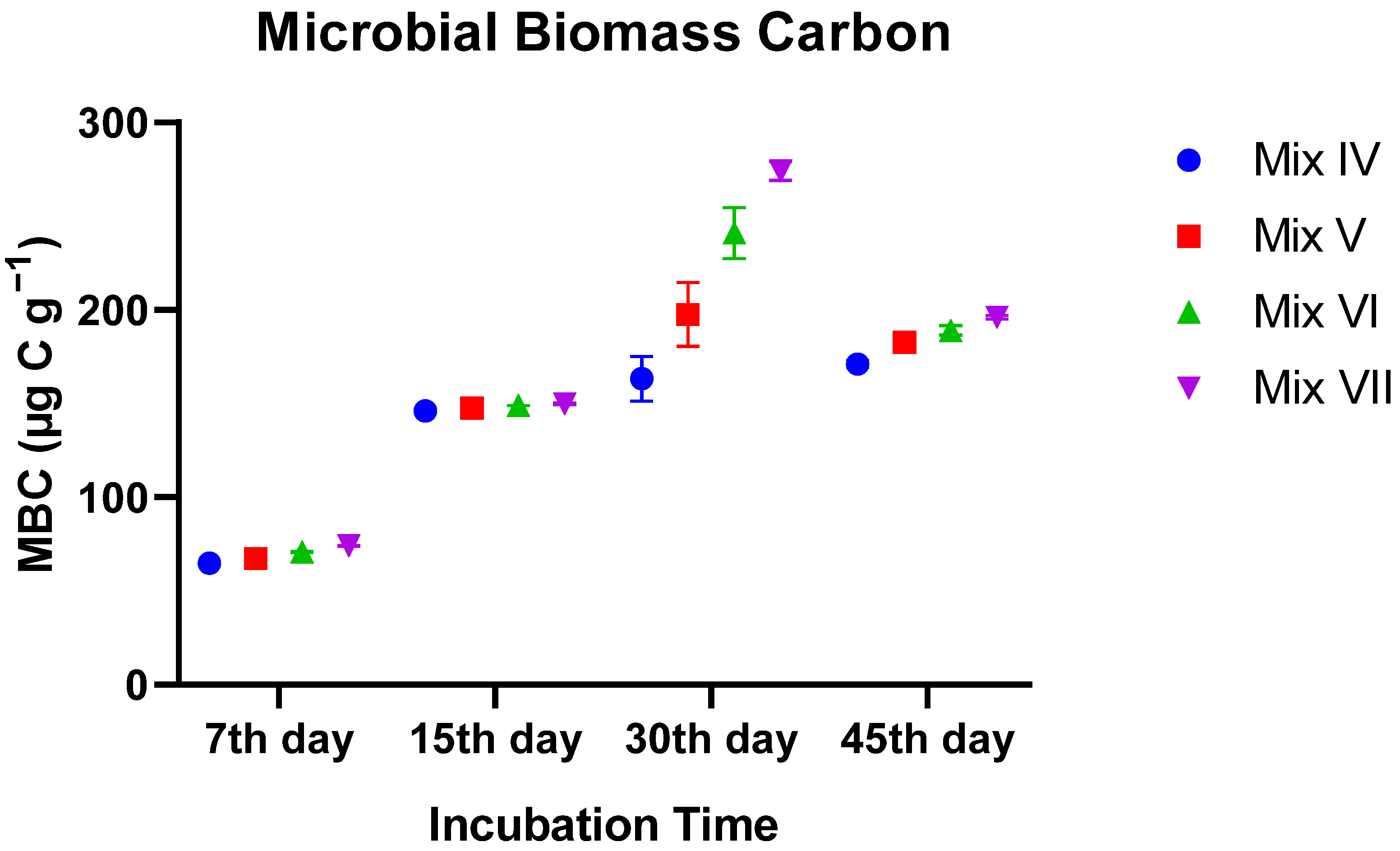

3.3.2. Microbial Biomass Carbon (MBC)

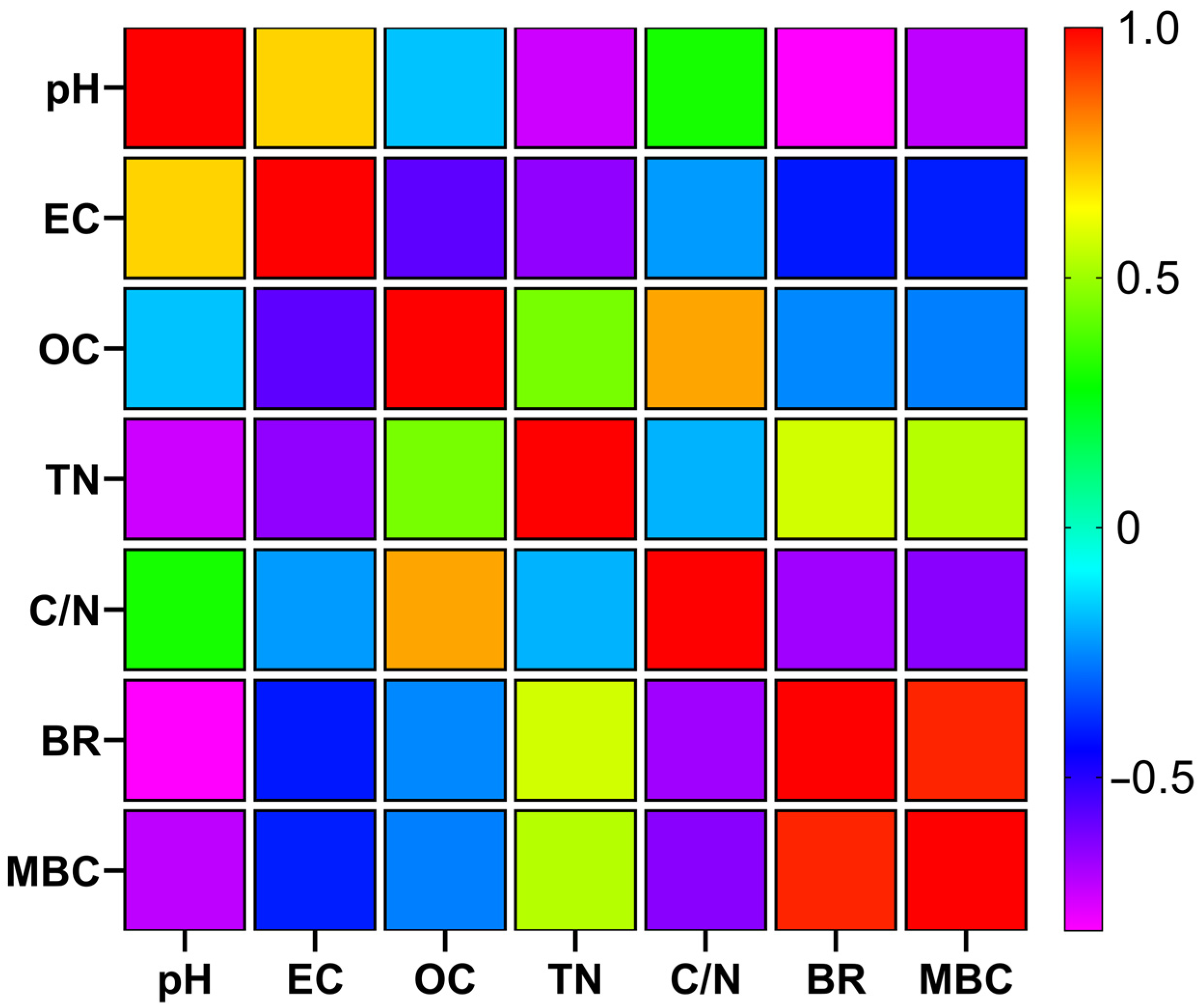

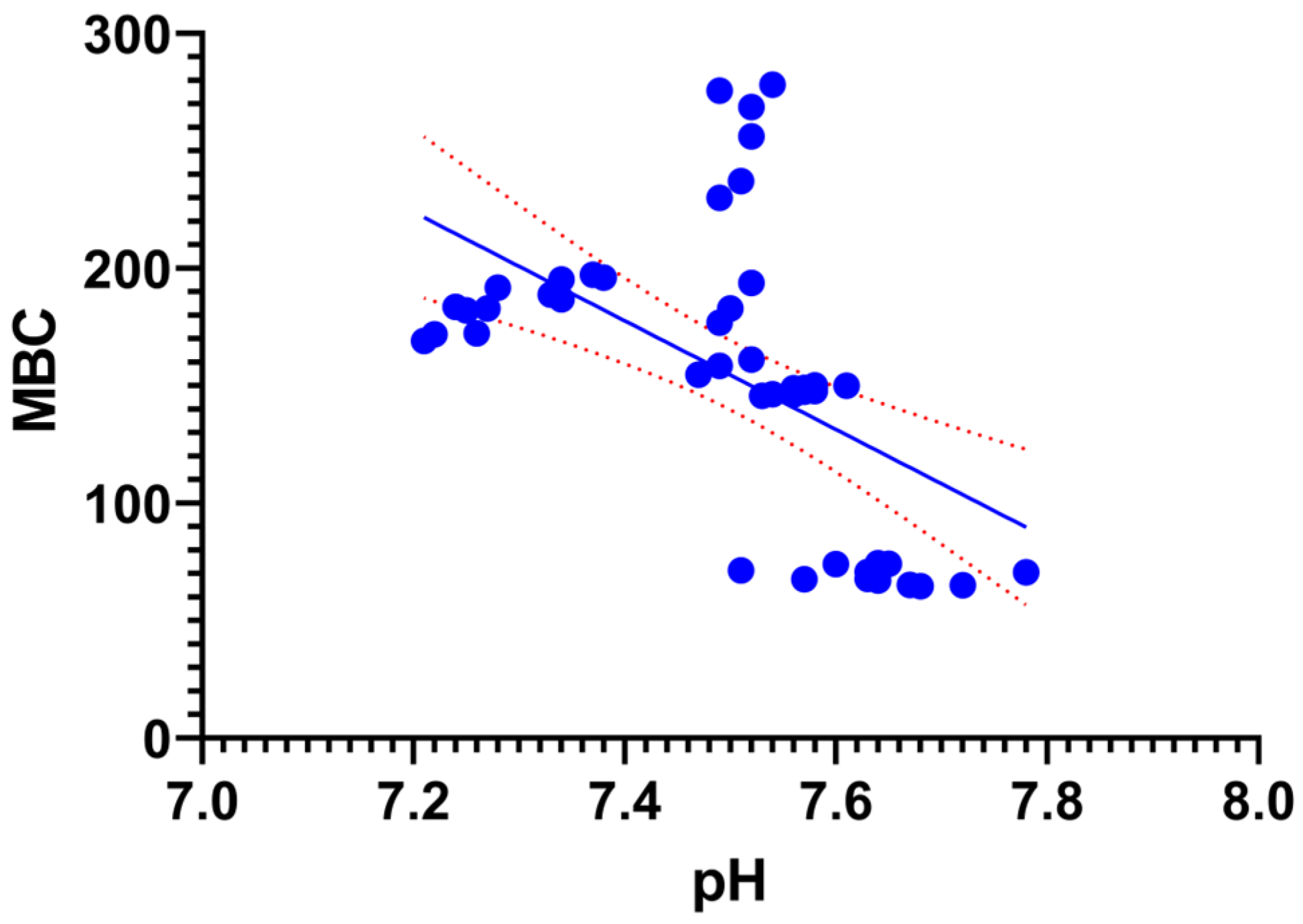

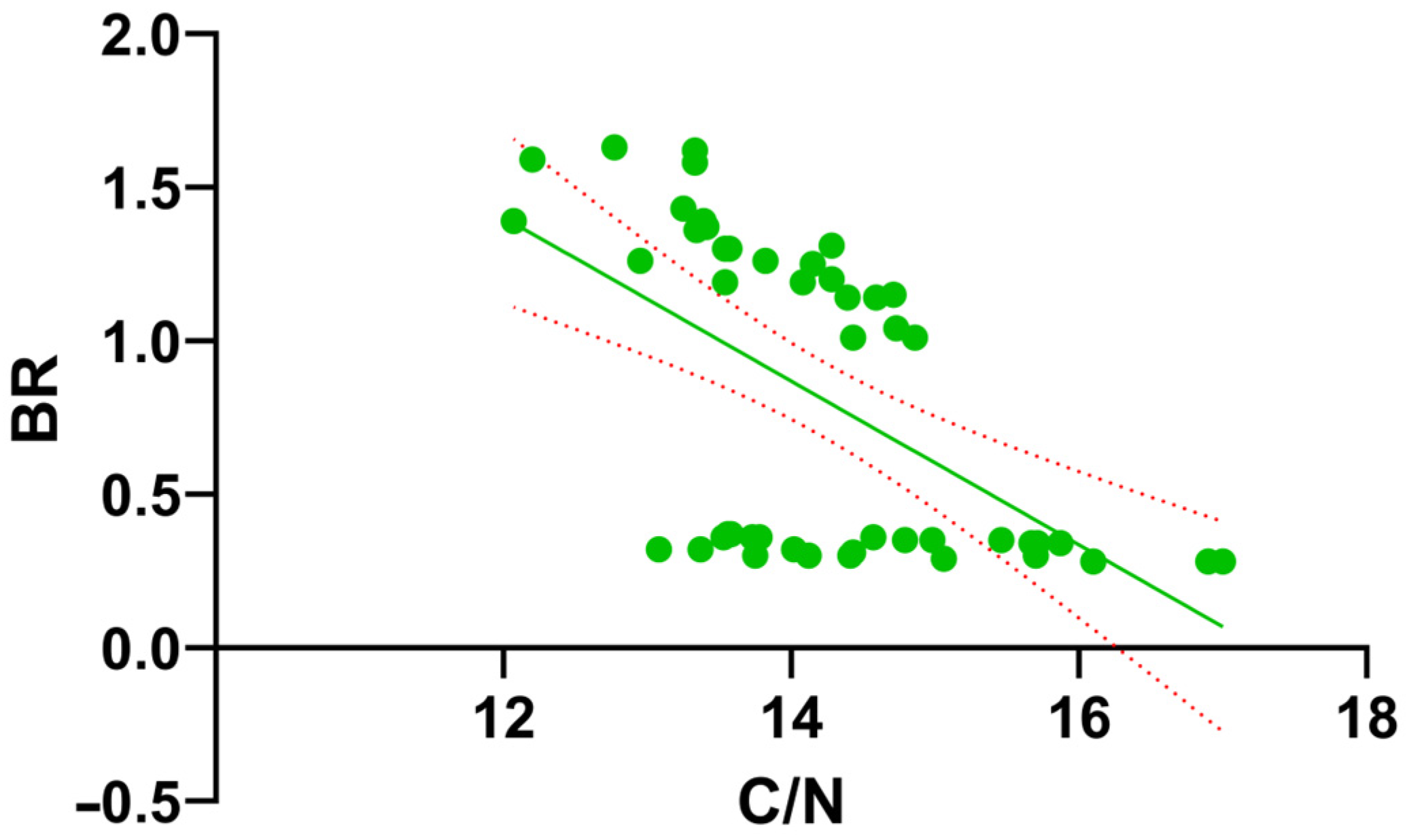

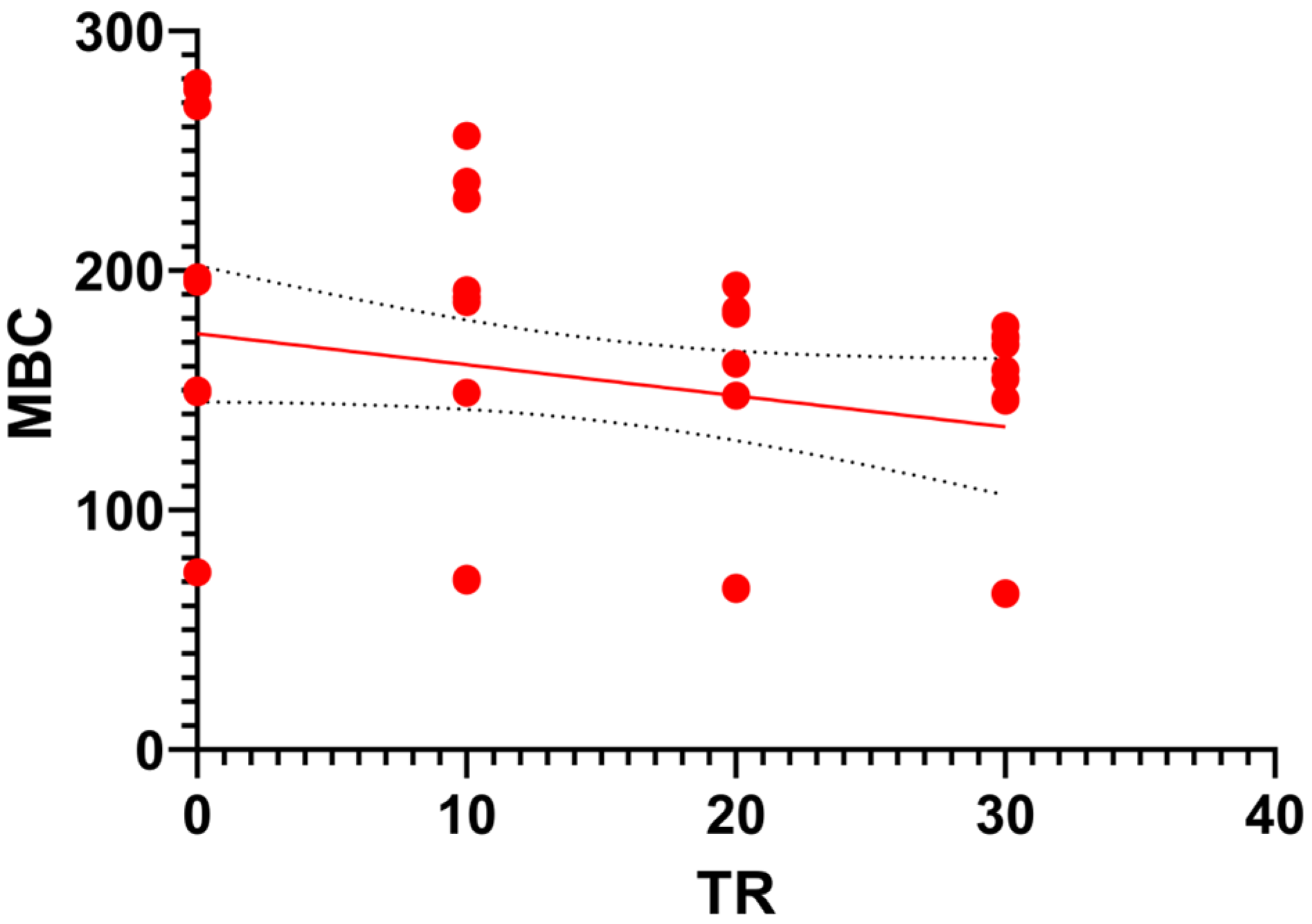

3.4. Interrelationships Between Physicochemical and Biological Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K.M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiafouli, M.A.; Thébault, E.; Sgardelis, S.P.; de Ruiter, P.C.; van der Putten, W.H.; Birkhofer, K.; Hemerik, L.; de Vries, F.T.; Bardgett, R.D.; Brady, M.V.; et al. Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, M.D.; Ay, A.; Ullah, I.; Demirkaya, S.; Kızılkaya, R.; Mihoub, A.; Zia, A.; Jamal, A.; Ghfar, A.A.; Di Serio, A.; et al. Vermicompost Rate Effects on Soil Fertility and Morpho-Physio-Biochemical Traits of Lettuce. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Managing soils for negative feedback to climate change and positive impact on food and nutritional security. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, R.M.; Lee, S.; Edwards, C.A.; Arancon, N.Q.; Metzger, J.D. The influence of humic acids derived from earthworm-processed organic wastes on plant growth. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 84, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkay, İ. From gene to green product: An integrated pipeline of biotechnology and green chemistry for sustainable phytochemical production. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2025, 30, 905–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkay, İ.; Öztürk, L. The form, dose, and method of application of vermicompost differentiate the phenylpropene biosynthesis in the peltate glandular trichomes of methylchavicol chemotype of Ocimum basilicum L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 198, 116688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkay, İ.; Öztürk, L.; Hepşen Türkay, F.Ş. Unveiling the role of vermicompost in modulating phenylpropanoid metabolism in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.): A single-cell type PGT approach. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 38, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture–Statistical Yearbook 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, P.V.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quina, M.J. Tomato Residue Management from a Biorefinery Perspective and towards a Circular Economy. Foods 2024, 13, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmuş, M.; Kızılkaya, R. The Effect of Tomato Waste Compost on Yield of Tomato and Some Biological Properties of Soil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, K.T.; Reid, B.J.; Fermor, T.R. Impact of composting strategies on the treatment of soils contaminated with organic pollutants. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 112, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupper, T.; Bucheli, T.D.; Brändli, R.C.; Ortelli, D.; Edder, P. Dissipation of pesticides during composting and anaerobic digestion of source-separated organic waste at full-scale plants. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7988–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, K.; Canonica, S.; Wackett, L.P.; Elsner, M. Evaluating Pesticide Degradation in the Environment: Blind Spots and Emerging Opportunities. Science 2013, 341, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo, E.; Villaverde, J. Advanced technologies for the remediation of pesticide-contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedo, J.; Wettstein, F.E.; Rösch, A.; Herzog, C.; Banerjee, S.; Büchi, L.; Charles, R.; Wächter, D.; Martin-Laurent, F.; Bucheli, T.D.; et al. Widespread Occurrence of Pesticides in Organically Managed Agricultural Soils—The Ghost of a Conventional Agricultural Past? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, M.; Hodson, M.E.; Delgado, E.A.; Baker, G.; Brussaard, L.; Butt, K.R.; Dai, J.; Dendooven, L.; Peres, G.; Tondoh, J.E.; et al. A review of earthworm impact on soil function and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılkaya, R.; Türkay, F.Ş.H. Vermicomposting of anaerobically digested sewage sludge with hazelnut husk and cow manure by earthworm Eisenia foetida. Compos. Sci. Util. 2014, 22, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Sauza, R.M.; Álvarez-Jiménez, M.; Delhal, A.; Reverchon, F.; Blouin, M.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Cerdán, C.R.; Guevara, R.; Villain, L.; Barois, I. Earthworms building up soil microbiota, a review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Z. Effects of Vermicompost on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. Crispa) Yield in Greenhouse under Different Soil Water Regimes. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 2151–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J.; Edwards, C.A. Biology and ecology of earthworm species used for vermicomposting. In Vermiculture Technology: Earthworms, Organic Waste and Environmental Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aira, M.; Monroy, F.; Dominguez, J. Earthworms strongly modify microbial biomass and activity triggering enzymatic activities during vermicomposting independently of the application rates of pig slurry. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 385, 252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.A.; Arancon, N.Q.; Sherman, R.L. Vermiculture Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kızılkaya, R.; Heps̨en, S. Effect of biosolid amendment on enzyme activities in earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) casts. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2004, 167, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwairakpam, M.; Bhargava, R. Vermitechnology for sewage sludge recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.K.; Kaushik, P.; Dilbaghi, N. Vermiconversion of wastewater sludge from textile mill mixed with anaerobically digested biogas plant slurry employing Eisenia foetida. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 65, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, D.; Narbonne, J.F.; Arnaud, C.; Saint-Denis, M. Biochemical responses of the earthworm Eisenia fetida andrei exposed to contaminated artificial soil, effects of carbaryl. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cang, T.; Zhao, X.; Yu, R.; Chen, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q. Comparative acute toxicity of twenty-four insecticides to earthworm, Eisenia fetida. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 79, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Estefan, G.; Rashid, A. Soil and Plant Analysis Laboratory Manual; ICARDA: Beirut, Lebanon, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen-total. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; SSSA Book Series 5; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.P. Soil respiration. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Agronomy Monograph 9; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 831–871. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.P.; Domsch, K.H. A physiological method for the quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1978, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Garg, V.K. Recycling of organic wastes by employing Eisenia fetida. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2874–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, J.C. Earthworm Biomarkers in Ecological Risk Assessment. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology: Continuation of Residue Reviews; Ware, G.W., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 85–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, P.; Ghosh, G.; Ghosal, P.; Banik, P. Changes in organic–C, N, P and K and enzyme activities in vermicompost of biodegradable organic wastes under liming and microbial inoculants. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.A.; Bohlen, P.J.; Hendrix, P.; Arancon, N. Biology and Ecology of Earthworms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaviraj; Sharma, S. Municipal solid waste management through vermicomposting employing exotic and local species of earthworms. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 90, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Domínguez, J. Comparison of the effectiveness of composting and vermicomposting for the biological stabilization of cattle manure. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira, C.; Sampedro, L.; Benitez, E.; Nogales, R. Vermicomposting of sludges from paper mill and dairy industries with Eisenia andrei: A pilot-scale study. Bioresour. Technol. 1998, 63, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Garg, V. Vermicomposting of mixed solid textile mill sludge and cow dung with the epigeic earthworm Eisenia foetida. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 90, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S. Vermicomposting of vegetable-market solid waste using Eisenia fetida: Impact of bulking material on earthworm growth and decomposition rate. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, A.; Bombach, P.; Schmidt-Brücken, B.; Kästner, M. SOM genesis: Microbial biomass as a significant source. Biogeochemistry 2012, 111, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Schimel, J.P.; Jastrow, J.D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, C.; Nogales, R.; Senesi, N.; Benitez, E.; Polo, A. Organic matter humification by vermicomposting of cattle manure alone and mixed with two-phase olive pomace. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5085–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S. Nutrient changes and biodynamics of epigeic earthworm Perionyx excavatus (Perrier) during recycling of some agriculture wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1608–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.K.; Parmelee, R.W. Earthworm secondary production and N flux in agroecosystems: A comparison of two approaches. Oecologia 2000, 124, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment. A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndegwa, P.M.; Thompson, S.A. Effects of C-to-N ratio on vermicomposting of biosolids. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 75, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.-H. Microbial eco-physiological indicators to assess soil quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 98, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Ladd, J. Microbial biomass in soil: Measurement and turnover. In Soil Biochemistry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 415–472. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.-H.; Domsch, K.H. Application of eco-physiological quotients (qCO2 and qD) on microbial biomasses from soils of different cropping histories. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1990, 22, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aira, M.; Monroy, F.; Domínguez, J. Eisenia fetida (Oligochaeta, Lumbricidae) Activates Fungal Growth, Triggering Cellulose Decomposition During Vermicomposting. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 52, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.-H.; Domsch, K.H. Soil microbial biomass: The eco-physiological approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.A.; Arancon, N.Q.; Sherman, R.L. Vermiculture Technology: Earthworms, Organic Wastes, and Environmental Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Virk, A.L.; Shakoor, A.; Ahmad, N.; Du, H.; Chang, S.X.; Cai, Y. Organic amendments restore soil biological properties under pesticides application. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 210, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, W.; Xu, W.; Yin, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L.; Duan, Y.; Lin, J.; Ferraro, D.O.; de Paula, R.; et al. Continental-scale characterization of pesticide cocktails in paddy soils: Associations with microbial community structure, function, and extracellular vesicle occurrence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Substrate Composition (w/w) |

|---|---|

| Mix I | 60% Tomato Residue + 40% Cattle Manure (60% TR + 40% CM) |

| Mix II | 50% Tomato Residue + 50% Cattle Manure (50% TR + 50% CM) |

| Mix III | 40% Tomato Residue + 60% Cattle Manure (40% TR + 60% CM) |

| Mix IV | 30% Tomato Residue + 70% Cattle Manure (30% TR + 70% CM) |

| Mix V | 20% Tomato Residue + 80% Cattle Manure (20% TR + 80% CM) |

| Mix VI | 10% Tomato Residue + 90% Cattle Manure (10% TR + 90% CM) |

| Mix VII | 0% Tomato Residue + 100% Cattle Manure (0% TR + 100% CM) |

| Analysis | Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Matter (OM) | Loss on ignition (550 °C) after H2SO4 pretreatment | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | Modified Kjeldahl method (Velp Scientifica) | Bremner [30] |

| C/N Ratio | Calculated as (OM/1.724)/TN | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| pH | Measured in a 1:10 (w/v) solid:distilled water suspension | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| EC (Electrical Conductivity) | Measured in a 1:10 (w/v) solid:distilled water suspension | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| Basal Respiration | CO2 evolution (Titrimetric measurement) | Anderson [31] |

| Microbial Biomass C | Substrate-induced respiration (SIR)—(glucose-induced respiration rate) | Anderson and Domsch [32] |

| Total Phosphorus (P) | Spectrophotometrically (yellow color method) | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| Total Potassium (K) | Flame photometer | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| Total Ca and trace elements (Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn) | Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) | Ryan, Estefan [29] |

| Analysis | Cattle Manure | Tomato Residue |

|---|---|---|

| pH 1:1 | 7.65 | 6.25 |

| EC 1:1 (µS cm−1) | 1523.56 | 2381.36 |

| Organic Matter, % | 35.866 | 88.743 |

| Organic Carbon (C), % | 20.734 | 51.470 |

| Total Nitrogen, % | 1.562 | 1.35 |

| Available Phosphorus, % | 2.533 | 0.96 |

| Potassium, me 100 g−1 | 3.747 | 0.42 |

| Ca + Mg, me 100 g−1 | 41.6 | 2.58 |

| Calcium, % | 1.895 | 1.92 |

| Iron, ppm | 4.62 | 447 |

| Copper, ppm | 3.72 | 381 |

| Zinc, ppm | 1.5361 | 153.25 |

| Manganese, ppm | 1.583 | 344 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hepşen Türkay, F.Ş. Biological Stability and Microbial Recovery Responses in Vermicomposting of Chemically Intensive Tomato Residues: Defining Management Limits. Toxics 2026, 14, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020129

Hepşen Türkay FŞ. Biological Stability and Microbial Recovery Responses in Vermicomposting of Chemically Intensive Tomato Residues: Defining Management Limits. Toxics. 2026; 14(2):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020129

Chicago/Turabian StyleHepşen Türkay, Fevziye Şüheda. 2026. "Biological Stability and Microbial Recovery Responses in Vermicomposting of Chemically Intensive Tomato Residues: Defining Management Limits" Toxics 14, no. 2: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020129

APA StyleHepşen Türkay, F. Ş. (2026). Biological Stability and Microbial Recovery Responses in Vermicomposting of Chemically Intensive Tomato Residues: Defining Management Limits. Toxics, 14(2), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020129