Breathing-Zone Exposure to Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds in Surgical Smoke During Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Prospective Paired Monitoring Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling Layout

2.2. VOCs Thermal Desorption Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

2.3. Formaldehyde (2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH)–High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Ultraviolet (UV) Detection; DNPH–HPLC/UV)

2.4. Data Handling and Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Case Characteristics

3.2. Breathing-Zone Versus Background Concentrations

3.3. Consistency Across Procedures and Aromatic Mixture Profile

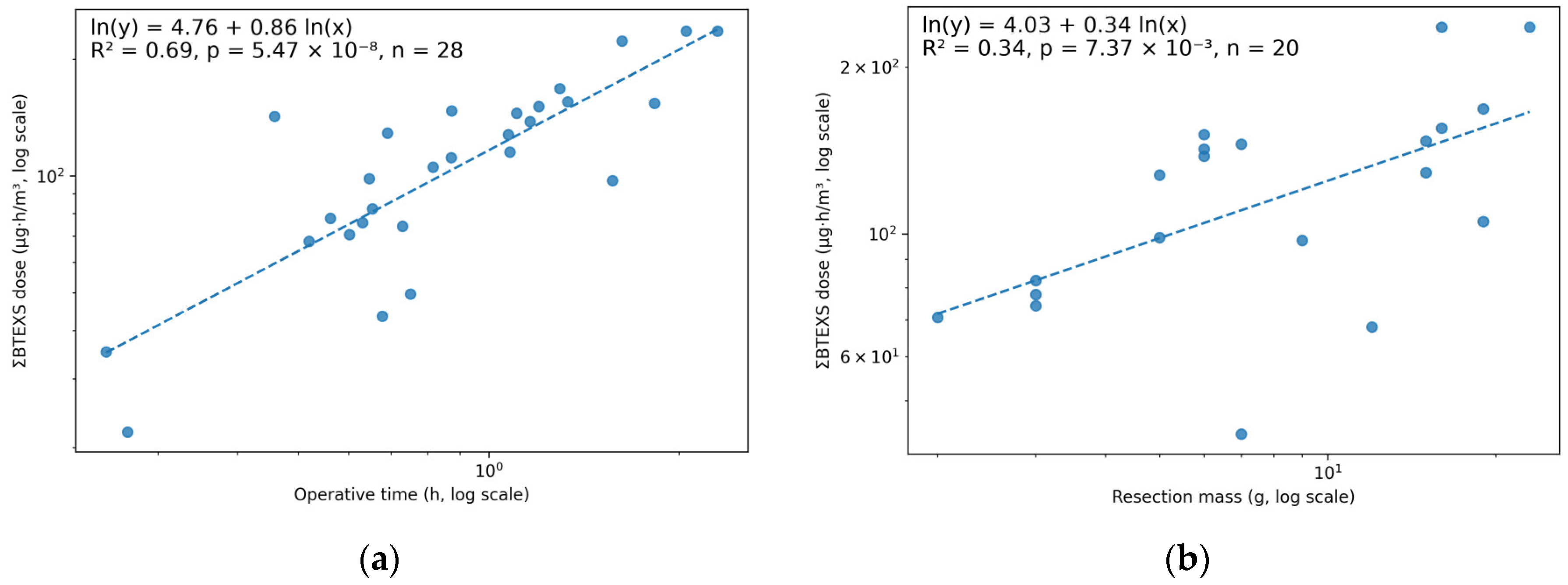

3.4. Dose Index and Associations with Operative Time and Resection Mass

3.5. Hazard Classification and Exposure Benchmarks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTEX | benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes |

| BTEXS | benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes, and styrene |

| DNPH | 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine |

| GC–MS | gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LEV | local exhaust ventilation |

| LOQ | limit of quantitation |

| TURBT | transurethral resection of bladder tumor |

| TVOC | total volatile organic compounds |

| ULPA | ultra-low particulate air |

| VOC | volatile organic compounds |

| ΣBTEXS | sum of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes, and styrene (toluene-equivalents) |

References

- Dixon, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Vasdev, N. A Systematic Review of the Harmful Effects of Surgical Smoke Inhalation on Operating Room Personnel. Health Sci. Rev. 2023, 6, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, W.L.; Garber, S.M. Surgical Smoke: A Review of the Literature. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüske-Hohlfeld, I.; Preissler, G.; Jauch, K.-W.; Pitz, M.; Nowak, D.; Peters, A.; Wichmann, H.-E. Surgical Smoke and Ultrafine Particles. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2008, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weld, K.J.; Dryer, S.; Ames, C.D.; Cho, K.; Hogan, C.; Lee, M.; Biswas, P.; Landman, J. Analysis of Surgical Smoke Produced by Various Energy-Based Instruments and Effect on Laparoscopic Visibility. J. Endourol. 2007, 21, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taravella, M.J.; Viega, J.; Luiszer, F.; Drexler, J.; Blackburn, P.; Hovland, P.; Repine, J.E. Respirable Particles in the Excimer Laser Plume. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2001, 27, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, R.; Stephenson, R.N.; Kutarski, P.W.; Parr, N.J. Chemical Composition of Gases Surgeons Are Exposed to During Endoscopic Urological Resections. Urology 2009, 74, 1152–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.J.; Lee, S.K.; Han, S.H.; Zhao, C.; Kim, M.K.; Park, S.C.; Park, J.K. Harmful Gases Including Carcinogens Produced during Transurethral Resection of the Prostate and Vaporization. Int. J. Urol. 2010, 17, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.K.; Chung, Y.J.; Park, J.K. Comparative Safety Analysis of Surgical Smoke from Transurethral Resection of the Bladder Tumors and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. Urology 2013, 82, 744.e9–744.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Lee, S.K.; Han, S.H.; Chung, Y.J.; Park, J.K. Comparison of Harmful Gases Produced During GreenLight High-Performance System Laser Prostatectomy and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. Urology 2012, 79, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Hazard Controls: HC-11. Control of Smoke from Laser/Electric Surgical Procedures; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- Williams, K. Guidelines in Practice: Surgical Smoke Safety. AORN J. 2022, 116, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.I.; Choi, M.C.; Jung, S.G.; Joo, W.D.; Lee, C.; Song, S.H.; Park, H. Chemicals in Surgical Smoke and the Efficiency of Built-in-Filter Ports. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2019, 23, e2019.00037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bree, K.; Barnhill, S.; Rundell, W. The Dangers of Electrosurgical Smoke to Operating Room Personnel: A Review. Workplace Health Saf. 2017, 65, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, G.E.; Ilce, A.; Lakestani, S.; Sit, M.; Avcioglu, F. Comparison of the Effects of Surgical Smoke on the Air Quality and on the Physical Symptoms of Operating Room Staff. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2023, 25, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-K.; Mo, F.; Ma, C.-G.; Dai, B.; Shi, G.-H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H.-L.; Ye, D.-W. Evaluation of Fine Particles in Surgical Smoke from an Urologist’s Operating Room by Time and by Distance. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2015, 47, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Method TO-17—Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Active Sampling onto Sorbent Tubes. In Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- ASTM D6196; Standard Practice for Selection of Sorbents, Sampling, and Thermal Desorption Analysis Procedures for Volatile Organic Compounds in Air. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d6196-03.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- ISO 16000-6:2021(En); Indoor Air—Part 6: Determination of Organic Compounds (VVOC, VOC, SVOC) in Indoor and Test Chamber Air by Active Sampling on Sorbent Tubes, Thermal Desorption and Gas Chromatography Using MS or MS FID. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:16000:-6:ed-3:v1:en (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Winberry, W.T.; Tejada, S.; Lonneman, B.; Kleindienst, T.; United States Environmental Protection Agency. Compendium Method TO-11A: Determination of Formaldehyde in Ambient Air Using Adsorbent Cartridge Followed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). In Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 16000-3; Indoor Air—Part 3: Determination of Formaldehyde and Other Carbonyl Compounds in Indoor and Test Chamber Air—Active Sampling Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Iraneta, P.; Seymour, M.J.; Kennedy, E.R. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM): Formaldehyde, Method 2016; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1998.

- Yeganeh, A.; Hajializade, M.; Sabagh, A.P.; Athari, B.; Jamshidi, M.; Moghtadaei, M. Analysis of Electrocautery Smoke Released from the Tissues Frequently Cut in Orthopedic Surgeries. World J. Orthop. 2020, 11, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maafa, I.M. Pyrolysis of Polystyrene Waste: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Shao, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhu, X. Chemical Composition of Surgical Smoke Produced during the Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure When Treating Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, M.-S.; Park, J.K.; Kim, K.-H.; Cho, S.-S.; Lee, K.-Y.; Shon, Z.-H. Emission and Cytotoxicity of Surgical Smoke: Cholesta-3,5-Diene Released from Pyrolysis of Prostate Tissue. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson-More, C.; Wu, T. A Knowledge Gap Unmasked: Viral Transmission in Surgical Smoke: A Systematic Review. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 2428–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. Benzene; International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2019.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-Tert-Butoxypropan-2-Ol; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 88; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2006.

- IARC. Styrene, Styrene-7,8-Oxide, and Quinoline; International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2019.

- IARC. Some Industrial Chemicals; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Ed.; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 2001.

- CDC. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards—Formaldehyde. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0293.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- 1910.1048-Formaldehyde; Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1048 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). IRIS Toxicological Review of Formaldehyde (Inhalation) CASRN 50-00-0—Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK612569/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Benzene Hazard Summary. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/benzene.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Kocher, G.J.; Koss, A.R.; Groessl, M.; Schefold, J.C.; Luedi, M.M.; Quapp, C.; Dorn, P.; Lutz, J.; Cappellin, L.; Hutterli, M.; et al. Electrocautery Smoke Exposure and Efficacy of Smoke Evacuation Systems in Minimally Invasive and Open Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Yoshizaki, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Hayakawa, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Sawa, Y.; Ito, K.; Kashiwabara, K.; Akamatsu, N.; et al. Effect of Smoke Evacuator on Reduction of Volatile Organic Compounds and Particles in Surgical Smoke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2024, 238, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, S.; Miller, A.; Eimer, B.C.; Shaffer, R.E. Filtration Performance of FDA-Cleared Surgical Masks. J. Int. Soc. Respir. Prot. 2009, 26, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A.; Willeke, K.; Marchloni, R.; Myojo, T.; Mckay, R.; Donnelly, J.; Liebhaber, F. Aerosol Penetration and Leakage Characteristics of Masks Used in the Health Care Industry. Am. J. Infect. Control 1993, 21, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhode Island Senate. SB 2237. 2018. Available online: https://open.pluralpolicy.com/ri/bills/2018/SB2237/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Benaim, E.H.; Jaspers, I. Surgical Smoke and Its Components, Effects, and Mitigation: A Contemporary Review. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 198, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| TURBT procedures (n) | 28 |

| Sampling days | 10 |

| Operative time (min) | 51 [IQR 39–73] (median [IQR]); 59.2 ± 31.0 (mean ± SD); range 15–138 |

| Resection mass (g) | 7.0 [IQR 5.0–15.2] (median [IQR]); 9.85 ± 6.43 (mean ± SD); range 2.0–23.0 |

| Analyte | Surgeon GM (GSD), µg/m3 | Background GM (GSD), µg/m3 | GMR (95% CI) | p (Paired t-Test on ln Ratios) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TVOC | 1201.11 (2.03) | 278.51 (2.09) | 4.31 (2.92–6.38) | <0.0001 |

| ΣBTEXS (Benzene + Toluene + Ethylbenzene + Xylenes + Styrene) | 118.85 (1.39) | 56.64 (1.69) | 2.10 (1.69–2.60) | <0.0001 |

| Benzene | 4.64 (1.52) | 2.92 (1.50) | 1.59 (1.39–1.82) | <0.0001 |

| Toluene | 60.82 (1.54) | 32.53 (1.88) | 1.87 (1.46–2.40) | <0.0001 |

| Ethylbenzene | 10.38 (1.38) | 6.52 (1.59) | 1.59 (1.32–1.92) | <0.0001 |

| Xylenes (Total) | 31.01 (1.64) | 12.65 (1.54) | 2.45 (1.91–3.15) | <0.0001 |

| Styrene | 6.77 (1.77) | 0.80 (1.95) | 8.51 (6.25–11.60) | <0.0001 |

| Formaldehyde | 11.02 (1.32) | 9.16 (1.59) | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 0.0023 |

| Dose Metric (µg·h/m3) | n (Time) | Spearman ρ vs. Operative Time | p (Time) | n (Mass) | Spearman ρ vs. Resection Mass | p (Mass) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΣBTEXS dose | 28 | 0.80 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.62 | 0.0038 |

| TVOC dose | 28 | 0.52 | 0.0047 | 20 | 0.39 | 0.09 |

| Benzene dose | 28 | 0.50 | 0.0066 | 20 | 0.35 | 0.134 |

| Toluene dose | 28 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.42 | 0.067 |

| Ethylbenzene dose | 28 | 0.81 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.59 | 0.0063 |

| Xylenes dose | 28 | 0.71 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.56 | 0.0098 |

| Styrene dose | 28 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.59 | 0.0061 |

| Formaldehyde dose | 28 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 20 | 0.48 | 0.032 |

| Substance | IARC Group | NIOSH REL | OSHA PEL | Key Hazards (Inhalation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans) | 0.1 ppm TWA; 1 ppm STEL | 1 ppm TWA; 5 ppm STEL | Hematotoxicity (bone marrow); leukemia risk; CNS symptoms |

| Formaldehyde | Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans) | Carcinogen: 0.016 ppm TWA; 0.1 ppm (15 min ceiling) | 0.75 ppm TWA; 2 ppm STEL | Strong mucosal/respiratory irritant; asthma-like symptoms; nasal cancer risk |

| Styrene | Group 2A (probably carcinogenic to humans) | 50 ppm TWA; 100 ppm STEL | 100 ppm TWA (also ceiling/peak in Table Z-2) | Eye/respiratory irritation; CNS depression; possible liver/reproductive effects |

| Ethylbenzene | Group 2B | 100 ppm TWA; 125 ppm STEL | 100 ppm TWA | Eye/respiratory irritation; CNS symptoms |

| Toluene | Group 3 (not classifiable as to carcinogenicity to humans) | 100 ppm TWA; 150 ppm STEL | 200 ppm TWA (also ceiling/peak in Table Z-2) | CNS effects (headache, dizziness); irritation; liver/kidney effects |

| Xylenes (o/m/p) | Group 3 (not classifiable as to carcinogenicity to humans) | 100 ppm TWA; 150 ppm STEL | 100 ppm TWA | Eye/respiratory irritation; CNS depression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jo, S.B.; Ahn, S.T.; Oh, M.M.; Shim, S.H.; Ahn, C.M.; Oh, S.G.; Kim, J.W. Breathing-Zone Exposure to Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds in Surgical Smoke During Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Prospective Paired Monitoring Study. Toxics 2026, 14, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020130

Jo SB, Ahn ST, Oh MM, Shim SH, Ahn CM, Oh SG, Kim JW. Breathing-Zone Exposure to Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds in Surgical Smoke During Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Prospective Paired Monitoring Study. Toxics. 2026; 14(2):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020130

Chicago/Turabian StyleJo, Seon Beom, Sun Tae Ahn, Mi Mi Oh, Soo Ho Shim, Cheong Mo Ahn, Seul Gi Oh, and Jong Wook Kim. 2026. "Breathing-Zone Exposure to Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds in Surgical Smoke During Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Prospective Paired Monitoring Study" Toxics 14, no. 2: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020130

APA StyleJo, S. B., Ahn, S. T., Oh, M. M., Shim, S. H., Ahn, C. M., Oh, S. G., & Kim, J. W. (2026). Breathing-Zone Exposure to Aromatic Volatile Organic Compounds in Surgical Smoke During Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor: A Prospective Paired Monitoring Study. Toxics, 14(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020130