Integrated ceRNA Network Analysis in Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Discovery of miRNA Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Silica

2.2. Establishment of a Silicosis Mouse Model

2.3. Pulmonary Function Test for Mice

2.4. Lung Tissue Collection and Treatment in Mice

2.5. Section Staining

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. Study Participants

2.8. Pulmonary Function Testing in Human Subjects

2.9. Collection and Processing of Human Peripheral Blood Samples

2.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR) Validation

2.11. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Silica Exposure Caused Pulmonary Fibrosis and Decreased Respiratory Function in Mice

3.2. Characterization of Sequencing Data in Lungs

3.3. Analysis of Differential Expression Genes

3.4. Enrichment Analysis of DEmRNAs, DEcircRNA, DElncRNAs, and DEmRNAs

3.5. Analysis of ceRNA Networks

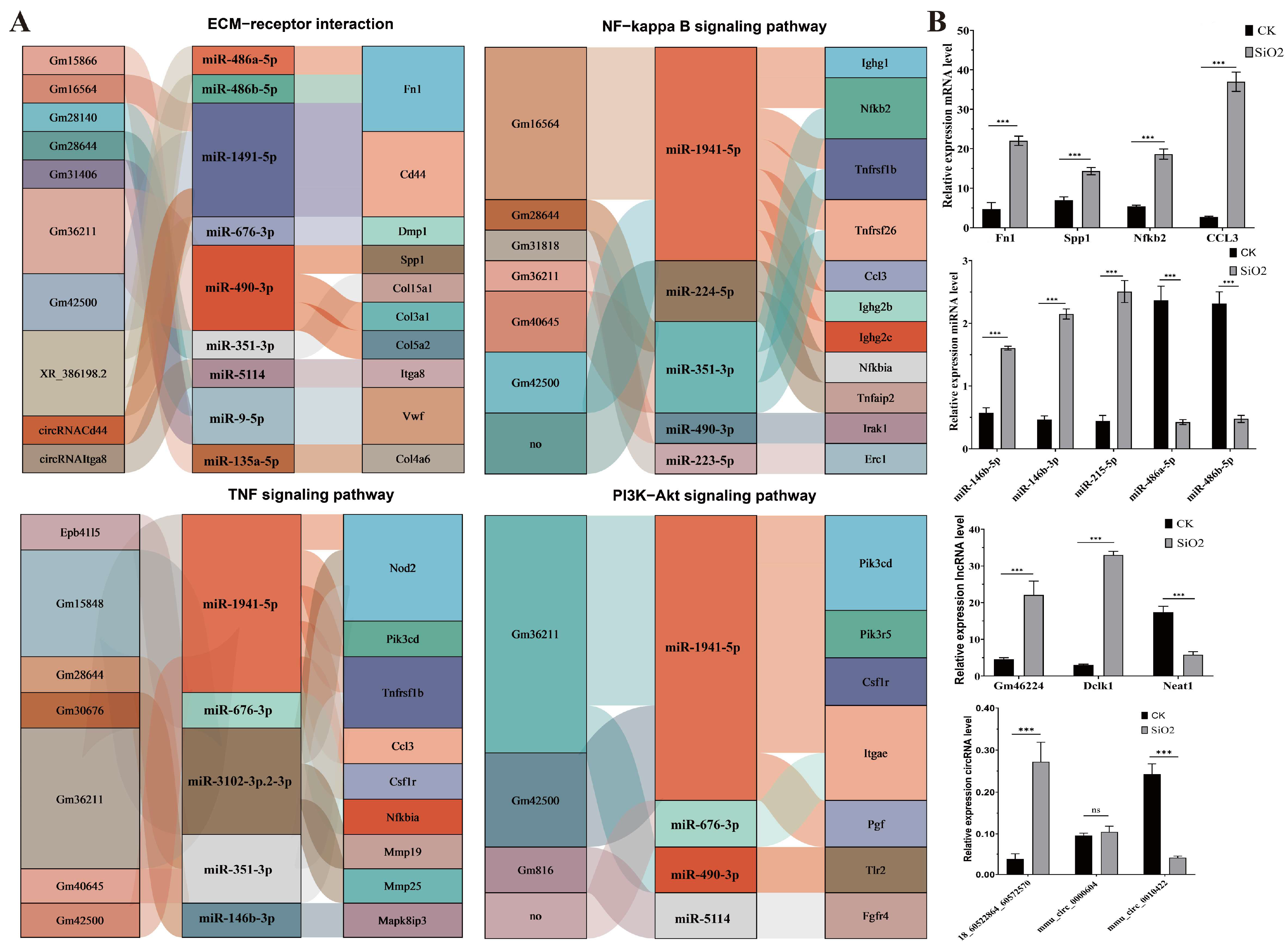

3.6. Identification of Core ncRNAs and Genes in Key Metabolic Pathways

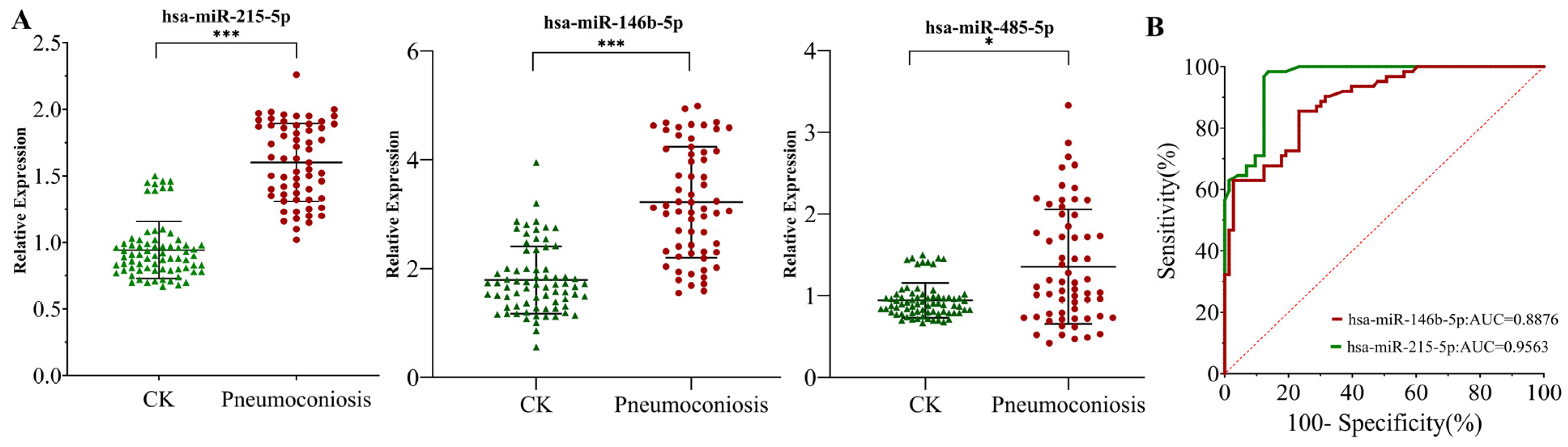

3.7. Expression Characteristics and Diagnostic Value of Candidate miRNAs in Pneumoconiosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ceRNA | competing endogenous RNA |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| CK | control group |

| SiO2 | silica-treated group |

| Ti | inspiratory time |

| Tv | tidal volume |

| Te | expiratory time |

| FVC | forced vital capacity |

| FEV1 | forced expiratory volume in one second |

| FVC% | percentage of predicted forced vital capacity |

| FEV1% | percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in one second |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin |

| RT-qPCR | quantitative real-rime PCR |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| DEmRNAs | differentially expressed genes |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| PTEN | phosphatase and yensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten |

| BMI | body mass index |

| EggNOG | evolutionary genealogy of genes: non-supervised orthologous groups |

| GO | gene ontology |

| KEGG | kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

References

- Howlett, P.; Gan, J.; Lesosky, M.; Feary, J. Relationship between cumulative silica exposure and silicosis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Thorax 2024, 79, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.C.; Yu, I.T.S.; Chen, W. Silicosis. Lancet 2012, 379, 2008–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanka, K.S.; Shukla, S.; Gomez, H.M.; James, C.; Palanisami, T.; Williams, K.; Chambers, D.C.; Britton, W.J.; Ilic, D.; Hansbro, P.M.; et al. Understanding the pathogenesis of occupational coal and silica dust-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, X.; Peng, C.; Meng, X.; Jia, Q. Silicosis: From pathogenesis to therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1516200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, R.F.; Jeebhay, M.F.; Cavalin, C.; Chen, W.; Cohen, R.A.; Fireman, E.; Go, L.H.T.; León-Jiménez, A.; Menéndez-Navarro, A.; Ribeiro, M.; et al. Current global perspectives on silicosis—Convergence of old and newly emergent hazards. Respirology 2022, 27, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, M.; Shang, B.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, D. Incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years due to silicosis worldwide, 1990–2019: Evidence from the global burden of disease study 2019. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 36910–36924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, P.; Han, L.; Zhou, P. Global incidence, prevalence and disease burden of silicosis: 30 years’ overview and forecasted trends. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Li, T. Prevention and treatment of pneumoconiosis in the context of healthy China 2030. China CDC Wkly 2023, 5, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupani, M.P. Challenges and opportunities for silicosis prevention and control: Need for a national health program on silicosis in India. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2023, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.L.; Mazurek, J.M. Trends in Pneumoconiosis Deaths—United States, 1999–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Moitra, S. Early Identification, Accurate Diagnosis, and Treatment of Silicosis. Can. Respir. J. 2022, 2022, 3769134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z. Silicon dioxide-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress of alveolar macrophages and its role on the formation of silicosis fibrosis: A review article. Toxicol. Res. 2023, 12, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.-T.; Sun, H.-F.; Han, Y.-X.; Zhan, Y.; Jiang, J.-D. The role of inflammation in silicosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1362509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamcakova, J.; Mokra, D. New Insights into Pathomechanisms and Treatment Possibilities for Lung Silicosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, H. A mechanistic review of silica-induced inhalation toxicity. Inhal. Toxicol. 2015, 27, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liang, Q.; Wang, F.; Yan, K.; Sun, M.; Lin, L.; Li, T.; Duan, J.; Sun, Z. Silica nanoparticles induce pulmonary autophagy dysfunction and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via p62/NF-κB signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 232, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DU, Y.; Huang, F.; Guan, L.; Zeng, M. Role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway-mediated macrophage autophagy in affecting the phenotype transformation of lung fibroblasts induced by silica dust exposure. J. Cent. South Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 48, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H.; Zhao, H.; Ge, D.; Liao, J.; Shao, L.; Mo, A.; Hu, L.; Xu, K.; Wu, J.; Mu, M.; et al. Necroptosis in pulmonary macrophages promotes silica-induced inflammation and interstitial fibrosis in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 355, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xie, Y.; Gu, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chen, W.; Ma, J. The emerging role of epigenetic regulation in the progression of silicosis. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Fan, H.; Hao, C.; Yao, W. Epigenetic changes and functions in pneumoconiosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2523066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, X.; Mei, L.; Zheng, M.; Yu, C.; Ye, M. Global DNA methylation and PTEN hypermethylation alterations in lung tissues from human silicosis. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 2185–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, L.; Bao, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Yue, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hao, C. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in lung fibroblasts co-cultured with silica-exposed alveolar macrophages. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, J.; Dimitrova, N. Transcription regulation by long non-coding RNAs: Mechanisms and disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, K.; Bayraktar, R.; Ferracin, M.; Calin, G.A. Non-coding RNAs in disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Xu, H.; Xiang, Q.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhan, J.-K.; He, J.-Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.-S. Roles and mechanisms of exosomal non-coding RNAs in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Mu, M.; Zhu, F.; Ye, D. Research and progress of miRNA as potential biomarkers for pneumoconiosis. Chin. J. Dis. Control. Prev. 2023, 27, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, E.; Zhou, S.; Han, R.; Wu, W.; Sun, G.; Cao, C.; Wang, R. RELA-mediated upregulation of LINC03047 promotes ferroptosis in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis via SLC39A14. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Ma, D.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Li, G.; Ni, C. circPVT1 promotes silica-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by modulating the miR-497-5p/TCF3 axis. J. Biomed. Res. 2024, 38, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, G.; Goyal, A.; Ilma, B.; Rekha, M.M.; Nayak, P.P.; Kaur, M.; Khachi, A.; Goyal, K.; Rana, M.; Rekha, A.; et al. Exosomal miRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in silicosis-related lung fibrosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Wei, Z.; Li, S.; Cai, W.; Mao, N.; Jin, F.; Li, Y.; Yi, X.; et al. Pulmonary silicosis alters microRNA expression in rat lung and miR-411-3p exerts anti-fibrotic effects by inhibiting MRTF-A/SRF signaling. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Shi, H.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Shi, B.; Yeo, A.J.; Lavin, M.F.; Jia, Q.; Shao, H.; Zhang, J. miRNA-34c-5p targets Fra-1 to inhibit pulmonary fibrosis induced by silica through p53 and PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Tian, Y.; Li, C.; Xia, J.; Qi, Y.; Yao, W.; Hao, C. LncRNA UCA1 regulates silicosis-related lung epithelial cell-to-mesenchymal transition through competitive adsorption of miR-204-5p. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 441, 115977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Huang, C.; Liu, L. Circular RNAs and their roles in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Su, X.; Kong, X.; Dong, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Whole transcriptome sequencing identifies key lncRNAs, circRNAs, and mRNAs for exploring the pathogenesis and therapeutic target of mouse pneumoconiosis. Gene 2024, 901, 148169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Mu, M.; Sun, Q.; Cao, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Hu, D.; Tao, X.; et al. A suitable silicosis mouse model was constructed by repeated inhalation of silica dust via nose. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 353, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 16180-2014; Standard for Identify Work Ability—Gradation of Disability Caused by Work-Related Injuries and Occupatiaonal Diseases. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Janssen, L.M.F.; Lemaire, F.; Marain, N.F.; Ronsmans, S.; Heylen, N.; Vanstapel, A.; Velde, G.V.; Vanoirbeek, J.A.J.; Pollard, K.M.; Ghosh, M.; et al. Differential pulmonary toxicity and autoantibody formation in genetically distinct mouse strains following combined exposure to silica and diesel exhaust particles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.F.; Hessel, P.A.; Nicolich, M. Relationship between silicosis and lung function. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2004, 30, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D.N.; Tallaksen, R.J. Silicosis. In Modern Occupational Diseases: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Management and Prevention; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, S.; Toro, F.; Ashurst, J.V. Physiology, Tidal Volume; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Z.; Zhuoya, J.; Juan, W.; Lu, L. The role of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in the regulation of lipid metabolism of alveolar macrophages in a model of silicosis induced by SiO2. Chin. J. Clin. Anat. 2022, 40, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-K.; Lee, S.-G.; Lee, J.Y.; Nam, H.-Y.; Lee, W.-k.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Lim, Y. Silica Induces Human Cyclooxygenase-2 Gene Expression Through the NF-kB Signaling Pathway. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2005, 24, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.-Z.; Cao, X.-K.; Liu, H.-Y.; Zheng, G.-Y.; Qian, Q.-Q.; Shen, F.-H. TNFR/TNF-α signaling pathway regulates apoptosis of alveolar macrophages in coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Komai, M.; Mihira, K.; Shimada, A.; Miyamoto, I.; Ogihara, K.; Naya, Y.; Morita, T.; Inoue, K.; Takano, H. Pathological Study on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Silicotic Lung Lesions in Rat. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naim, M.J. Pulmonary Fibrosis: Causes, Development, Diagnosis, and Treatment with Emphasis on Murine and in vitro Models. Curr. Respir. Med. Rev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Han, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M.; Cao, W.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, M.; Cui, G.; Du, Z.; et al. CircRNA-mediated ceRNA network: Micron-sized quartz silica particles induce apoptosis in primary human airway epithelial cells. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2025, 35, 1419–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xia, J.; Yao, W.; Yang, G.; Tian, Y.; Qi, Y.; Hao, C. Mechanism of LncRNA XIST/ miR-101–3p/ZEB1 axis in EMT associated with silicosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 360, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.; Zi-ming, J.; Xue-yan, T.; Wen-xuan, H.; Fa-xuan, W. LncRNA MRAK052509 competitively adsorbs miR-204-3p to regulate silica dust-induced EMT process. Environ. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 3628–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Sun, W.; Ma, D.; Ni, C. Long noncoding RNA-SNHG20 promotes silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by miR-490-3p/TGFBR1 axis. Toxicology 2021, 451, 152683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.T.; Florez-Sampedro, L.; Tasena, H.; Faiz, A.; Noordhoek, J.A.; Timens, W.; Postma, D.S.; Hackett, T.L.; Heijink, I.H.; Brandsma, C.-A. miR-146a-5p plays an essential role in the aberrant epithelial–fibroblast cross-talk in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1602538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Yao, S.; Zhang, G.; Xue, R.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, R.; Gao, H. Down-Regulation of miR-19a as a Biomarker for Early Detection of Silicosis. Anat. Rec. 2016, 299, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, E.M.S.; Mizutani, R.F.; Terra-Filho, M.; Ubiratan de Paula, S. Biomarkers related to silicosis and pulmonary function in individuals exposed to silica. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Shao, H.; Du, Z. The value of single biomarkers in the diagnosis of silicosis: A meta-analysis. iScience 2024, 27, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Yao, L.; Hu, Z.; Wu, S.; Zou, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; et al. Serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 as a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of silicosis: A case-control study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yao, Y.; Guo, C.; Dai, P.; Huang, J.; Peng, P.; Wang, M.; Dawa, Z.; Zhu, C.; Lin, C. Trichodelphinine A alleviates pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting collagen synthesis via NOX4-ARG1/TGF-β signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boina, B.B.; Jing, Z.; Harpreet, S.; Yutong, Z. Intracellular Chloride Channels: A Rising Target in Lung Disease Research. J. Respir. Biol. Transl. Med. 2025, 2, 10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Tian, H.; Rong, H.; Ai, P.; Li, X. LncRNA PVT1 induces apoptosis and inflammatory response of bronchial epithelial cells by regulating miR-30b-5p/BCL2L11 axis in COPD. Genes Environ. 2023, 45, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, G.; Pecoraro, G.; Pane, K.; Franzese, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Vitagliano, L.; Salvatore, M. The Oncosuppressive Properties of KCTD1: Its Role in Cell Growth and Mobility. Biology 2023, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Tian, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Cheng, S.; Sun, H. MiR-146b-5p inhibits Candida albicans-induced inflammatory response through targeting HMGB1 in mouse primary peritoneal macrophages. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Pneumoconiosis (n = 62) | Control (n = 73) | t/χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 50.69 ± 3.43 | 49.86 ± 3.20 | −1.454 | 0.148 |

| Waistline, cm, mean ± SD | 88.59 ± 10.43 | 90.34 ± 7.68 | −1.092 | 0.277 |

| Hipline, cm, mean ± SD | 98.70 ± 6.53 | 99.08 ± 6.12 | −0.348 | 0.728 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 24.17 ± 4.13 | 25.35 ± 3.64 | −1.737 | 0.085 |

| Education level | 43.317 | <0.001 | ||

| College degree and above | 17 (27.42%) | 61 (83.56%) | ||

| High school and below | 45 (72.58%) | 12 (16.44%) | ||

| Shift work | 8.11 | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 47 (75.8%) | 38 (52.1%) | ||

| No | 15 (24.2%) | 35 (47.9%) | ||

| Annual household income | 0.202 | 0.653 | ||

| <CNY 200,000 | 27 (43.54%) | 29 (39.73%) | ||

| ≥CNY 200,000 | 35 (56.45%) | 44 (60.27%) | ||

| Hypertension | 5.454 | 0.020 | ||

| Yes | 22 (35.5%) | 13 (17.8%) | ||

| No | 40 (64.5%) | 60 (82.2%) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 7.992 | 0.005 | ||

| Yes | 15 (24.2%) | 5 (6.8%) | ||

| No | 47 (75.8%) | 68 (93.2%) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.791 | 0.374 | ||

| Yes | 8 (12.90%) | 6 (8.22%) | ||

| No | 54 (87.10%) | 67 (91.78%) | ||

| Smoking | 3.638 | 0.056 | ||

| Yes | 52 (83.87%) | 51 (69.86%) | ||

| No | 10 (16.13%) | 22 (30.14%) | ||

| Drinking | 3.479 | 0.062 | ||

| Yes | 24 (38.71%) | 40 (54.80%) | ||

| No | 38 (61.29%) | 33 (45.20%) | ||

| FEV1% | 70.90 ± 16.98 | 81.12 ± 19.74 | 3.194 | 0.002 |

| FEV1/FVC% | 88.06 ± 11.43 | 91.45 ± 11.75 | 1.688 | 0.094 |

| FVC% | 81.36 ± 19.39 | 89.33 ± 20.20 | 2.328 | 0.021 |

| ID | OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-215-5p | 1.966 (1.6938,2.2796) | <0.001 |

| hsa-miR-485-5p | 1.028 (0.9138,1.2585) | 0.640 |

| hsa-miR-146b-5p | 1.9367 (1.697–2.201) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Jin, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, F.; Mu, M. Integrated ceRNA Network Analysis in Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Discovery of miRNA Biomarkers. Toxics 2026, 14, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010063

Wang J, Jin Y, Chen Q, Zhu F, Mu M. Integrated ceRNA Network Analysis in Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Discovery of miRNA Biomarkers. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jia, Yuting Jin, Qianwei Chen, Fenglin Zhu, and Min Mu. 2026. "Integrated ceRNA Network Analysis in Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Discovery of miRNA Biomarkers" Toxics 14, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010063

APA StyleWang, J., Jin, Y., Chen, Q., Zhu, F., & Mu, M. (2026). Integrated ceRNA Network Analysis in Silica-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Discovery of miRNA Biomarkers. Toxics, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010063