Characteristics and Key Genetic Pathway Analysis of Cr(VI)-Resistant Bacillus subtilis Isolated from Contaminated Soil in Response to Cr(VI)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

2.2. Isolation and Identification of B. subtilis from High-Cr(VI) Soils

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of B. subtilis

2.4. Establishment of B. subtilis Model to Respond to High-Cr(VI) Stress

2.4.1. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

2.4.2. RNA Isolation and Sequencing Analysis

2.5. Measurement of the Bacterium’s Safety

2.5.1. Animal Treatments

2.5.2. Tissue Preparation

2.5.3. Sample Histology

2.5.4. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

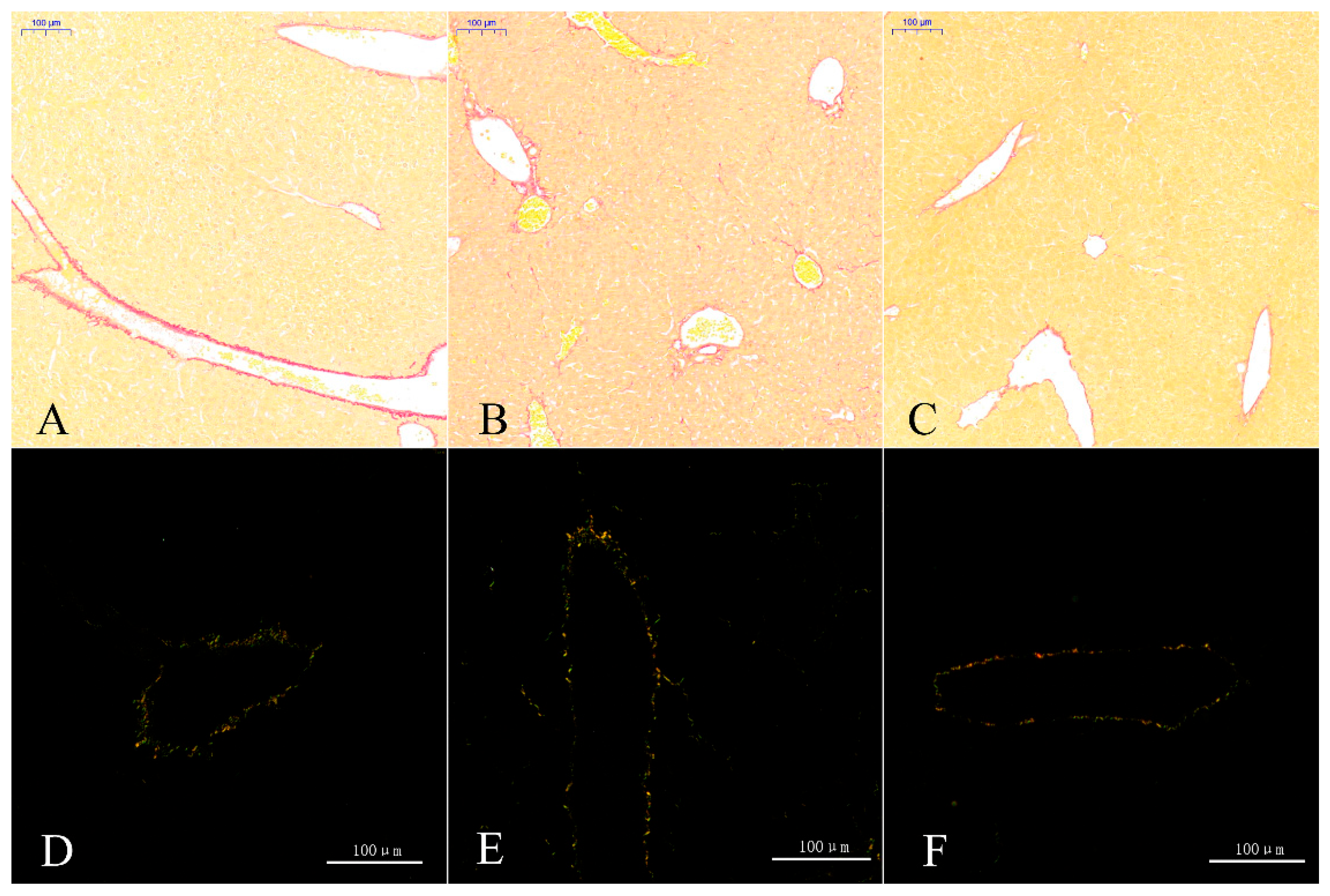

2.5.5. Sirius Scarlet Staining of Liver

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Distribution and Traits of Bacillus

3.2. SEM and TEM of F3 and T2 Isolates

3.3. Genome Sequencing

3.4. RNA Sequencing

3.5. Safety Assessment of B. subtilis

3.5.1. HE Staining

3.5.2. FISH

3.5.3. Sirius Scarlet Staining

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of Cr(VI) and the Role of B. subtilis in Remediation

4.2. Morphological and Biochemical Characteristics of the Isolates

4.3. Genomic and RNA-Seq Results—Adaptive Mechanisms

4.4. Probiotic Potential and In Vivo Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laxmi, V.; Kaushik, G. Toxicity of Hexavalent Chromium in Environment, Health Threats, and Its Bioremediation and Detoxification from Tannery Wastewater for Environmental Safety. In Bioremediation of Industrial Waste for Environmental Safety; Saxena, G., Bharagava, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, S.P.; Parakh, S.K.; Tong, Y.W. Health hazards of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) and its microbial reduction. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 4923–4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokarram, M.; Saber, A.; Sheykhi, V. Effects of heavy metal contamination on river water quality due to release of industrial effluents. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigalenok, Y.; Tazhibayeva, A.; Kokhmetova, S.; Starodubtseva, A.; Kan, T.; Isbergenova, D.; Malchik, F. Hexavalent chromium at the crossroads of science, environment and public health. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 21439–21464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mir, R.A.; Tyagi, A.; Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S.; Mushtaq, M.; Raina, A.; Park, S.; Sharma, S.; Mir, Z.A.; et al. Chromium Toxicity in Plants: Signaling, Mitigation, and Future Perspectives. Plants 2023, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukhurebor, K.E.; Aigbe, U.O.; Onyancha, R.B.; Nwankwo, W.; Osibote, O.A.; Paumo, H.K.; Ama, O.M.; Adetunji, C.O.; Siloko, I.U. Effect of hexavalent chromium on the environment and removal techniques: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkou, A.K.; Vaclavikova, M.; Gallios, G.P. Impregnated Activated Carbons with Binary Oxides of Iron-Manganese for Efficient Cr (VI) Removal from Water. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.A.; Sattar, S.; Nawaz, R.; Al-Hussain, S.A.; Rizwan, M.; Bukhari, A.; Waseem, M.; Irfan, A.; Inam, A.; Zaki, M.E. Enhancing chromium removal and recovery from industrial wastewater using sustainable and efficient nanomaterial: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 263, 115231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, S.; Oh, S. A review on microbial-integrated techniques as promising cleaner option for removal of chromium, cadmium and lead from industrial wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Mangaiyarkarasi, M.S.; Vincent, S.; Janarthanan, S.; Subba Rao, T.; Tata, B.V. Bioreduction of Cr(VI) by alkaliphilic Bacillus subtilis and interaction of the membrane groups. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 18, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Bioreduction of hexavalent chromium via Bacillus subtilis SL-44 enhanced by humic acid: An effective strategy for detoxification and immobilization of chromium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129234. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, B.; Hao, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, H.; Lu, A. Bioremediation potential of Cr (VI) by Lysinibacillus cavernae CR-2 isolated from chromite-polluted soil: A promising approach for Cr (VI) detoxification. Geomicrobiol. J. 2023, 41, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Wu, B.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Z. Strategy for enhancing Cr (VI)-contaminated soil remediation and safe utilization by microbial-humic acid-vermiculite-alginate immobilized biocomposite. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 243, 113956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thar Annam, S.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Mahmood, R. Characterization of chromium remediating bacterium Bacillus subtilis isolated from electroplating effluent. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2012, 2, 961–966. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, W.W.; Bankston, P.W. Measurement of live bacteria by Nomarski interference microscopy and stereologic methods as tested with macroscopic rod-shaped models. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesie Taye, G.; Bule, M.; Alemayehu Gadisa, D.; Teka, F.; Abula, T. In vivo antidiabetic activity evaluation of aqueous and 80% methanolic extracts of leaves of Thymus schimperi (Lamiaceae) in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 3205–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). EUCAST Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 13.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Duan, Q.; Huang, L.; Bi, J. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from industrial and agricultural regions in China: Pollution and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I. Bioremediation techniques for polluted environment: Concept, advantages, limitations, and prospects. In Trace Metals in the Environment-New Approaches and Recent Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, M.H. Global status of tetracycline resistance among clinical isolates of Vibrio cholerae: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2021, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, M.; Lagier, J.C.; Raoult, D.; Khelaifia, S. Bacterial culture through selective and non-selective conditions: The evolution of culture media in clinical microbiology. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 34, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Lin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Deng, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Xia, Z. Biochemical and genetic basis of cadmium biosorption by Enterobacter ludwigii LY6, isolated from industrial contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Tapias, D.F.; Helmann, J.D. Roles and regulation of Spx family transcription factors in Bacillus subtilis and related species. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2019, 75, 279–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, H.; Heinz, A.; Sudzinová, P.; Voß, M.; Hantke, I.; Krásný, L.; Turgay, K. Spx, the central regulator of the heat and oxidative stress response in B. subtilis, can repress transcription of translation-related genes. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Turgay, K. Spx, a versatile regulator of the Bacillus subtilis stress response. Curr. Genet. 2019, 65, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Tapias, D.F.; Helmann, J.D. Induction of the Spx regulon by cell wall stress reveals novel regulatory mechanisms in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 107, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T.K.; Petersen, I.B.; Xu, L.; Barbuti, M.D.; Mebus, V.; Justh, A.; Alqarzaee, A.A.; Jacques, N.; Oury, C.; Thomas, V.; et al. The Spx stress regulator confers high-level β-lactam resistance and decreases susceptibility to last-line antibiotics in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e00335-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.Y.; Park, M.; Park, J.-I.; Kim, J.K.; Yum, S.; Kim, Y.-J. Transcriptomic Changes Induced by Low and High Concentrations of Heavy Metal Exposure in Ulva pertusa. Toxics 2023, 11, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamri, I.; Radloff, M.; Hohmann, K.F.; Nimbarte, V.D.; Nasiri, H.R.; Bolte, M.; Safarian, S.; Michel, H.; Schwalbe, H. Synthesis and Biological Screening of new Lawson Derivatives as selective substrate-based Inhibitors of Cytochrome bo3 Ubiquinol Oxidase from Escherichia coli. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudan, S.; Flick, R.; Nong, L.; Li, J. Potential probiotic Bacillus subtilis isolated from a novel niche exhibits broad range antibacterial activity and causes virulence and metabolic dysregulation in Enterotoxic E. coli. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S.; Husain, I.; Sharma, A. Purification and characterization of phytase from Bacillus subtilis P6: Evaluation for probiotic potential for possible application in animal feed. Food Front. 2022, 3, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur Sidhu, M.; Lyu, F.; Sharkie, T.P.; Ajlouni, S.; Ranadheera, C.S. Probiotic yogurt fortified with chickpea flour: Physico-chemical properties and probiotic survival during storage and simulated gastrointestinal transit. Foods 2020, 9, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzantini, D.; Celandroni, F.; Calvigioni, M.; Panattoni, A.; Labella, R.; Ghelardi, E. Microbiological Quality and Resistance to an Artificial Gut Environment of Two Probiotic Formulations. Foods 2021, 10, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathiriya, M.R.; Vekariya, Y.V.; Hati, S. Understanding the Probiotic Bacterial Responses Against Various Stresses in Food Matrix and Gastrointestinal Tract: A Review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2023, 15, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkhairi Amin, F.A.; Sabri, S.; Ismail, M.; Chan, K.W.; Ismail, N.; Esa, N.M.; Lila, M.A.M.; Zawawi, N. Probiotic Properties of Bacillus Strains Isolated from Stingless Bee (Heterotrigona itama) Honey Collected across Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourceau, P.; Geier, B.; Suerdieck, V.; Bien, T.; Soltwisch, J.; Dreisewerd, K.; Liebeke, M. Visualization of metabolites and microbes at high spatial resolution using MALDI mass spectrometry imaging and in situ fluorescence labeling. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 3050–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biochemical Tube Test | Isolates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | N2 | N3 | N4 | T1 | T2 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| bile | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| D-mannitol | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| propionate | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 7% NaCl | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| nitrate | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| D-xylose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| L-arabinose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| starch | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| pH 5.7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 80 °C growth | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Susceptibility to Antibiotics | Isolates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | N2 | N3 | N4 | T1 | T2 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| penicillin | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| cefotaxime | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| kanamycin | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| streptomycin | ES | ES | HS | ES | HS | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| gentamicin | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| tetracycline | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| doxycycline | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| erythromycin | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES | ES |

| lincomycin | ES | ES | ES | MS | MS | ES | MS | ES | ES |

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Chromosome number | 1 |

| Genome size (bp) | 4,054,239 |

| GC content (%) | 43.60 |

| Protein coding genes (CDSs) | 4160 |

| rRNA | 30 |

| tRNA | 86 |

| Sample | Total Reads | Clean Reads | Percentage of Clean Reads | Clean Bases | GC Content | % > Q20 | % > Q30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr-1 | 9,099,616 | 9,066,906 | 99.64% | 1,360,035,900 | 44.53% | 98.05% | 93.94% |

| Cr-2 | 10,259,728 | 10,226,208 | 99.67% | 1,533,923,748 | 44.42% | 98.12% | 94.05% |

| Cr-3 | 10,661,038 | 10,622,664 | 99.64% | 1,593,392,448 | 44.25% | 98.12% | 94.09% |

| F-1 | 9,565,790 | 9,537,602 | 99.71% | 1,430,640,300 | 45.51% | 98.27% | 94.38% |

| F-2 | 8,621,352 | 8,595,512 | 99.70% | 1,289,326,800 | 45.29% | 98.20% | 94.23% |

| F-3 | 8,911,376 | 8,863,334 | 99.46% | 1,329,494,046 | 45.54% | 97.98% | 93.79% |

| Gene Category | Gene Name | Gene ID | Expression Pattern Under Cr(VI) Stress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold shock protein gene | Csp | CPEAOFNH_02613 | Up-regulated |

| Transcriptional regulatory protein gene | Spx, SenS | CPEAOFNH_00606, CPEAOFNH_00312 | Up-regulated |

| Beta-lactam resistance gene | - | CPEAOFNH_00182 | Up-regulated |

| Cysteine transmembrane transporter gene | - | CPEAOFNH_00345, CPEAOFNH_00942, CPEAOFNH_04023 | Up-regulated |

| Metal ion binding and phosphopantothenate-cysteine ligase gene | CoaBC | CPEAOFNH_01085 | Up-regulated |

| Cysteine anabolic gene | Prp, - (hydrolase), - (synthase), - (biosynthesis of L-cysteine from sulfate), - (cystathionine), - (selenocysteine) | CPEAOFNH_02135, CPEAOFNH_03592, CPEAOFNH_02063/CPEAOFNH_03655, CPEAOFNH_02062, CPEAOFNH_03655, CPEAOFNH_03587 | Up-regulated |

| Bacterial regulatory protein gene | - (gntR family), - (tetR family) | CPEAOFNH_00338/CPEAOFNH_03465, CPEAOFNH_02787 | Up-regulated |

| Anaerobic regulatory protein gene | - | CPEAOFNH_03180 | Up-regulated |

| Beta-lactam resistance gene | - | CPEAOFNH_00476, CPEAOFNH_03819 | Down-regulated |

| Transcriptional regulator protein gene | CtsR, YvrH, LevR, NatR, DegU, YhcZ, YxjL, CitT, YvfU, DesR, Hpr, AlsR | CPEAOFNH_03680, CPEAOFNH_02747, CPEAOFNH_02044, CPEAOFNH_03935, CPEAOFNH_02977, CPEAOFNH_00390, CPEAOFNH_03341, CPEAOFNH_00179, CPEAOFNH_02833, CPEAOFNH_01472, CPEAOFNH_00452, CPEAOFNH_03042 | Down-regulated |

| Cysteine anabolic gene | - (homocysteine S-methyltransferase), MetC (cysteine lyase), - (biosynthesis of L-cysteine from sulfate) | CPEAOFNH_00554, CPEAOFNH_00646, CPEAOFNH_02771 | Down-regulated |

| Cytochrome ubiquinol oxidase subunit | - (cytochrome c), - (cytochrome c oxidase subunit I/II/III/IV) | CPEAOFNH_00791, CPEAOFNH_01002/CPEAOFNH_01001/CPEAOFNH_01003/CPEAOFNH_01905/CPEAOFNH_01004 | Down-regulated |

| Cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor gene | CtaG, - | CPEAOFNH_01005, CPEAOFNH_02213 | Down-regulated |

| Ubiquinol–cytochrome c reductase complex gene | - | CPEAOFNH_01628, CPEAOFNH_01629, CPEAOFNH_01630 | Down-regulated |

| Cytochrome bd terminal oxidase subunit I gene | CPEAOFNH_02456 | Down-regulated |

| GO.ID | Term | Annotated | Significant | Expected | KS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0006200 | ATP catabolic process | 188 | 17 | 11.2 | 1.2 × 10−17 |

| GO:0006468 | protein phosphorylation | 1416 | 79 | 84.38 | 8.2 × 10−15 |

| GO:0050665 | hydrogen peroxide biosynthetic process | 96 | 9 | 5.72 | 1.90 × 10−12 |

| GO:0007169 | transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway | 136 | 14 | 8.1 | 2.5 × 10−12 |

| GO:0045010 | actin nucleation | 182 | 6 | 10.85 | 2.80 × 10−12 |

| GO:0007062 | sister chromatid cohesion | 140 | 4 | 8.34 | 1.70 × 10−11 |

| GO:0019344 | cysteine biosynthetic process | 337 | 58 | 20.08 | 4.40 × 10−11 |

| GO:0016926 | protein deSUMOylation | 89 | 4 | 5.3 | 4.80 × 10−11 |

| GO:0006364 | rRNA processing | 328 | 57 | 19.55 | 9.50 × 10−11 |

| No. | Term | ID | Input Number | Background Number | p-Value | Corrected p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ribosome | ko03010 | 40 | 57 | 0.0011 | 0.1176 |

| 2 | Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis | ko00290 | 13 | 13 | 0.0090 | 0.4880 |

| 3 | Fatty acid metabolism | ko01212 | 20 | 29 | 0.0210 | 0.7570 |

| 4 | C5-branched dibasic acid metabolism | ko00660 | 9 | 9 | 0.0287 | 0.7762 |

| 5 | Fatty acid biosynthesis | ko00061 | 16 | 24 | 0.0447 | 0.8671 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, M.; Zheng, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, P.; Liu, J. Characteristics and Key Genetic Pathway Analysis of Cr(VI)-Resistant Bacillus subtilis Isolated from Contaminated Soil in Response to Cr(VI). Toxics 2026, 14, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010053

Zhu Y, Chen P, Li M, Zheng Q, Li J, Zhang F, Zheng P, Liu J. Characteristics and Key Genetic Pathway Analysis of Cr(VI)-Resistant Bacillus subtilis Isolated from Contaminated Soil in Response to Cr(VI). Toxics. 2026; 14(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yiran, Peng Chen, Muzi Li, Qi Zheng, Jianing Li, Fuliang Zhang, Pimiao Zheng, and Jianzhu Liu. 2026. "Characteristics and Key Genetic Pathway Analysis of Cr(VI)-Resistant Bacillus subtilis Isolated from Contaminated Soil in Response to Cr(VI)" Toxics 14, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010053

APA StyleZhu, Y., Chen, P., Li, M., Zheng, Q., Li, J., Zhang, F., Zheng, P., & Liu, J. (2026). Characteristics and Key Genetic Pathway Analysis of Cr(VI)-Resistant Bacillus subtilis Isolated from Contaminated Soil in Response to Cr(VI). Toxics, 14(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010053