Forecasting Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Qingdao City Using Deep Learning and Hybrid Interpretable Models and Analysis of Driving Factors Using SHAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

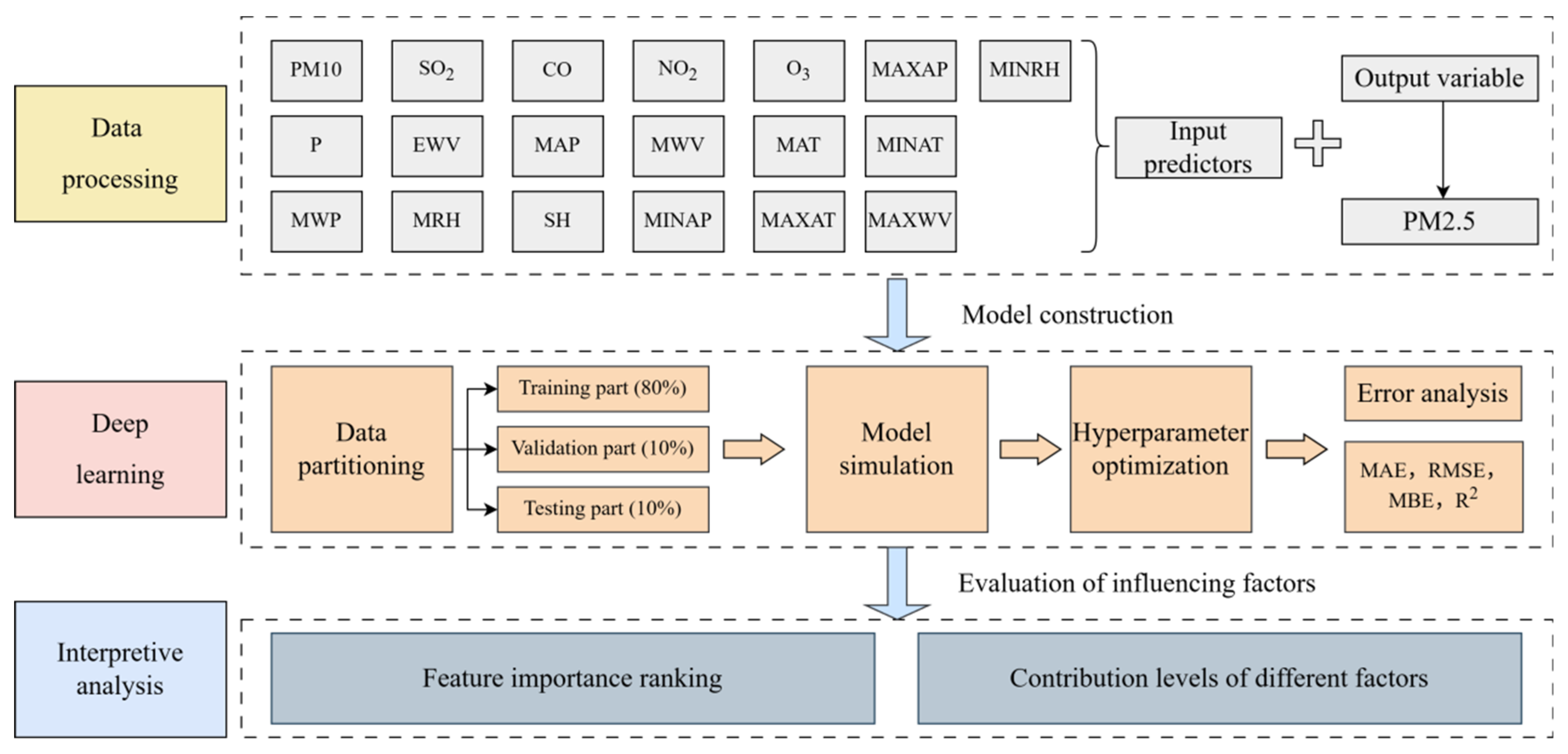

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

2.3. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

2.4. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

2.5. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)

2.6. Transformer

2.7. CNN–BiLSTM–Transformer

2.8. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

2.9. Evaluation Indices

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Between Input Variables and PM2.5

3.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

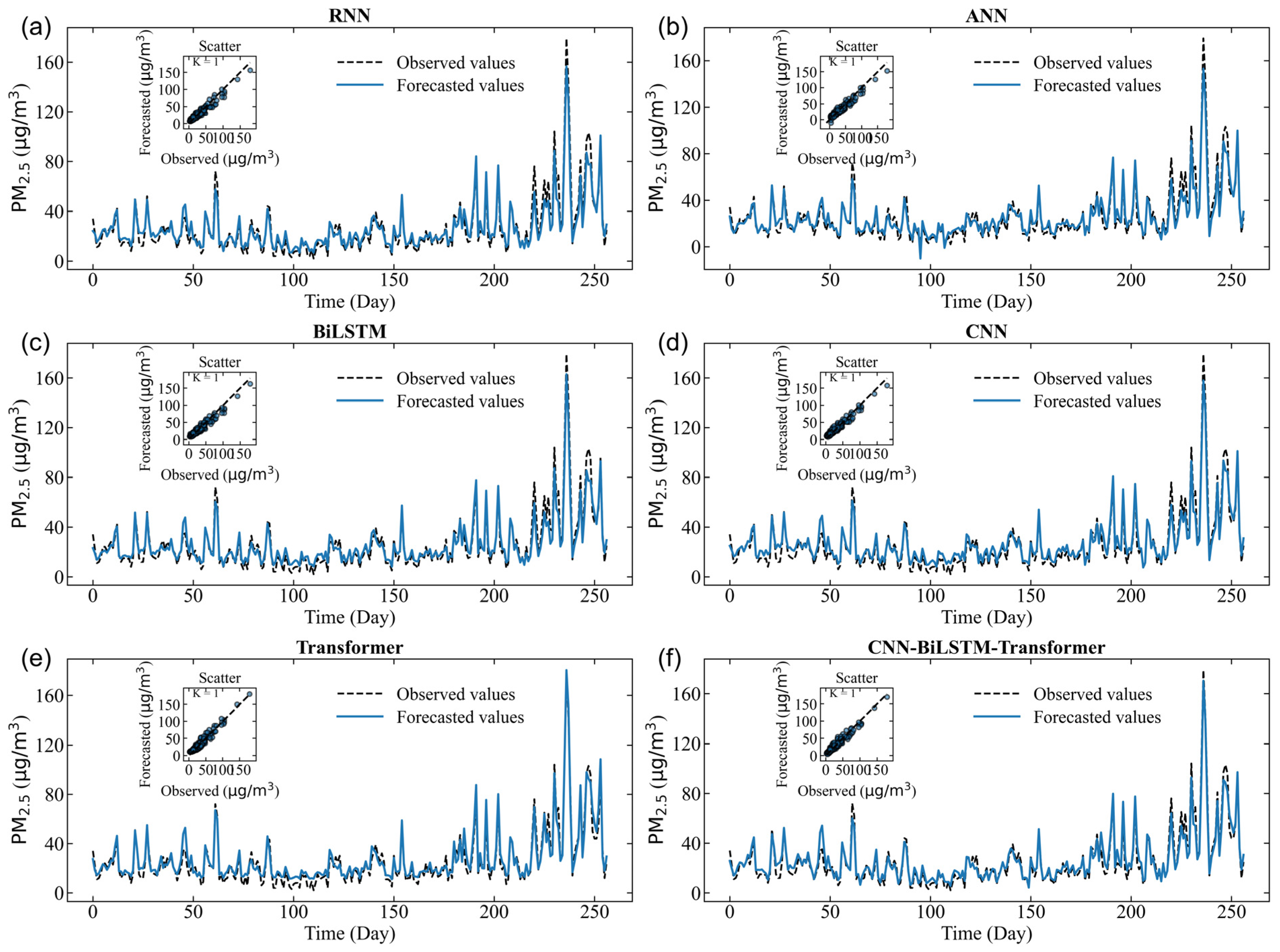

3.3. Performance Comparison of the Deep Learning and Hybrid Models

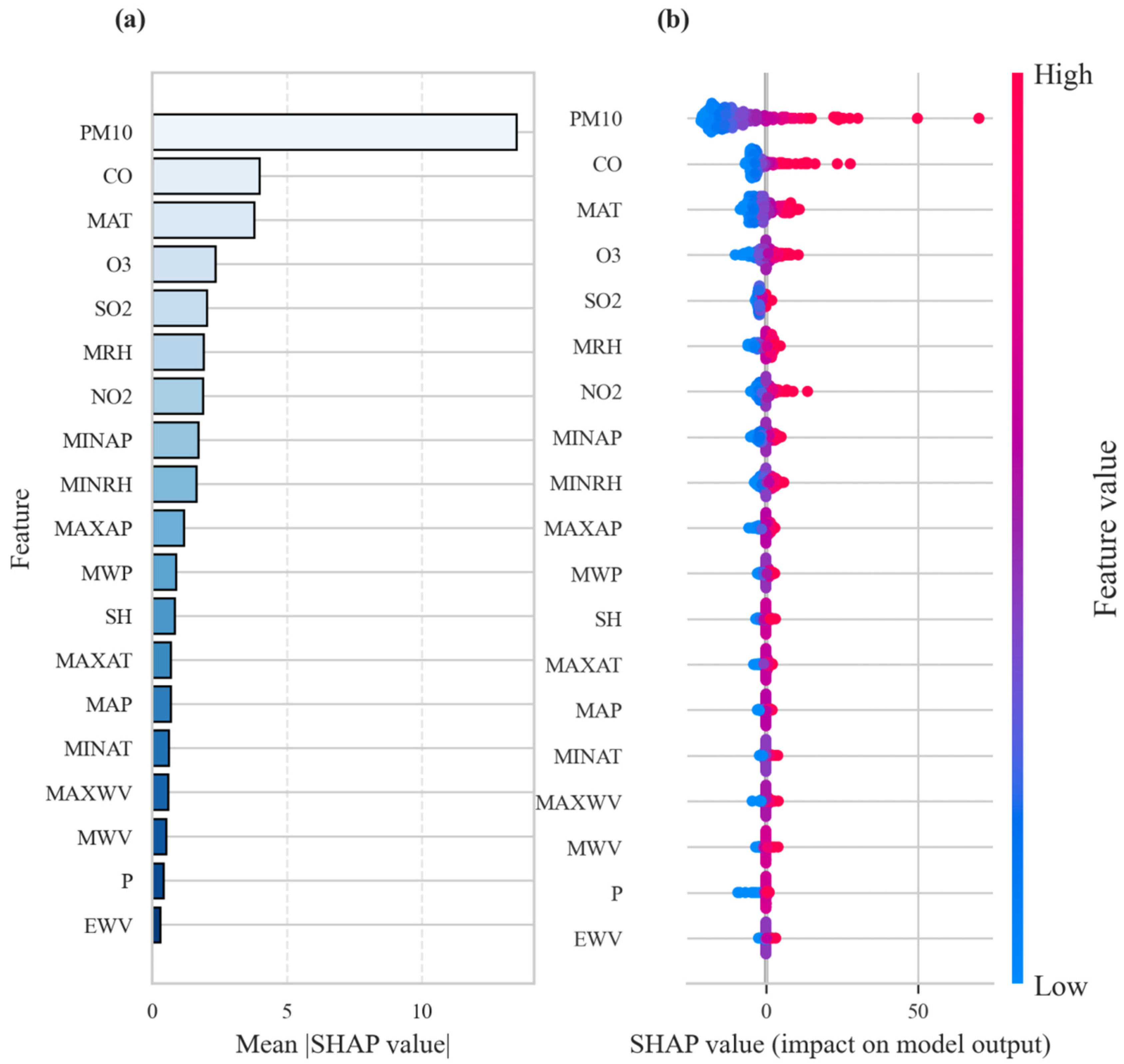

3.4. Interpretability Analysis

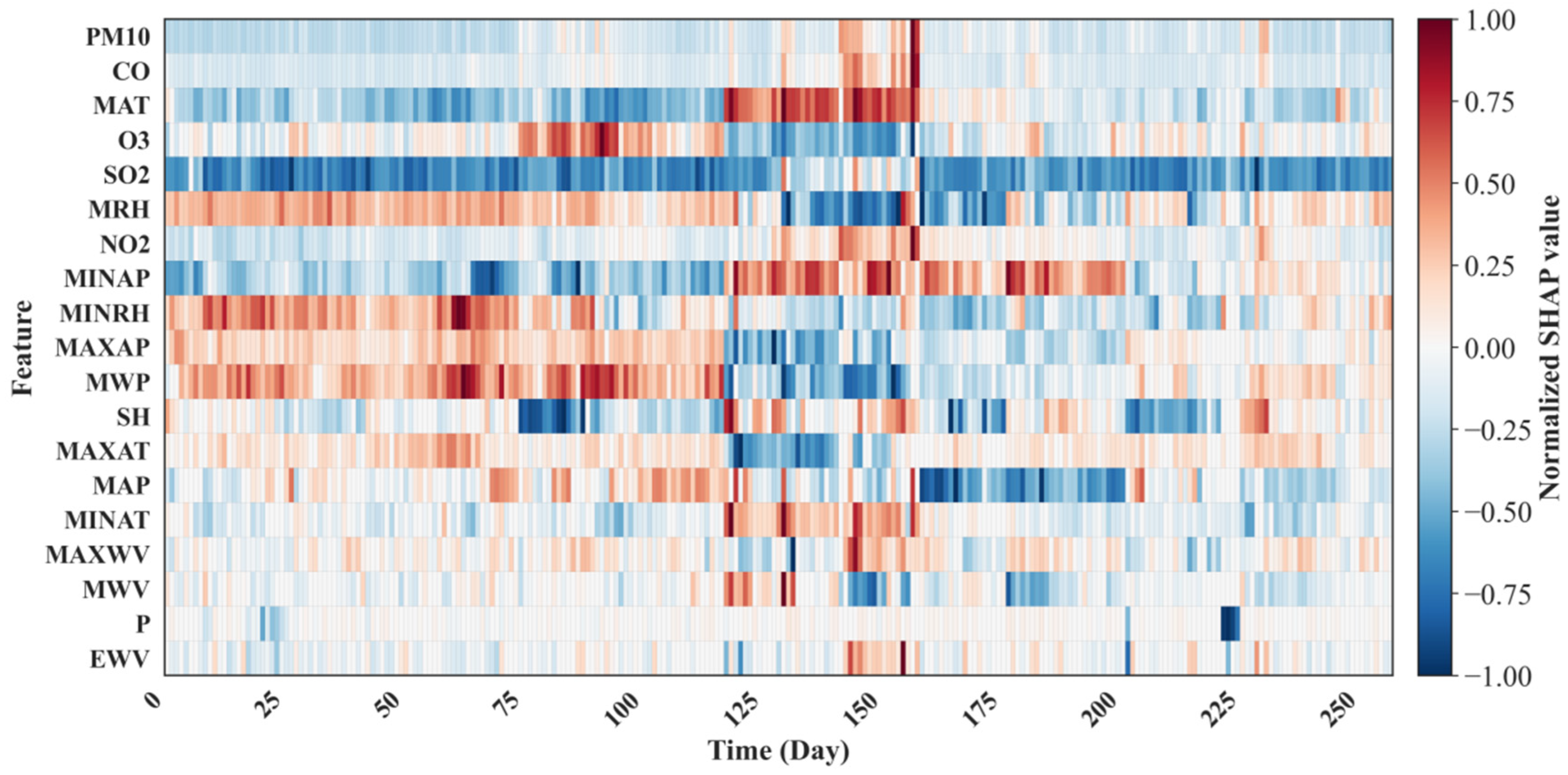

3.5. Visualizing Feature Contributions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Reis, S.; Li, Y.; Gu, B. Integrated livestock sector nitrogen pollution abatement measures could generate net benefits for human and ecosystem health in China. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Quaas, J. Nonlinearity of the cloud response postpones climate penalty of mitigating air pollution in polluted regions. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.S.; Dominici, F.; Gouveia, N.; Kelly, F.J.; Neira, M. Air pollution interventions for health. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2888–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; An, Y.; Dang, Y.; Ye, L. Research on accumulative time-delay effects between economic development and air pollution based on a novel grey relational analysis model. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 497, 145128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Chan, K.; Chen, X.; Wei, J.; Deng, F.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Hospital admissions attributable to reduced air pollution due to clean-air policies in China. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Daioglou, V.; Vreedenburgh, L.; Doelman, J.; Downward, G.; Matias de Pinho, M.G.; van Vuuren, D. Modelling PM2.5 reduction scenarios for future cardiopulmonary disease reduction. Nat. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Jin, L.N.; Zhao, B.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wu, Q.; et al. Control of toxicity of fine particulate matter emissions in China. Nature 2025, 643, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Koutrakis, P.; Michanikou, A.; Kouis, P.; Panayiotou, A.G.; Kinni, P.; Tymvios, F.; Chrysanthou, A.; Neophytou, M.; Mouzourides, P.; et al. Indoor residential and outdoor sources of PM2.5 and PM10 in Nicosia, Cyprus. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, B.; Hao, D.; Du, Z.; Wang, Q.; Song, Z.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Short-term PM2.5 exposure induces transient lung injury and repair. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; He, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Shi, P.; Moallemi, E.A.; Xu, F.; Yang, Y.; Qi, X.; Ma, Q.; et al. Substantially reducing global PM2.5-related deaths under SDG3.9 requires better air pollution control and healthcare. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, N.a.; Ean, L.W.; Ahmed, A.N.; Abdul Malek, M.; Chow, M.F. PM2.5 forecasting for an urban area based on deep learning and decomposition method. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Lang, J. Trends in Air Pollutant Concentrations and the Impact of Meteorology in Shandong Province, Coastal China, during 2013–2019. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 200545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, C.; Kwan, M.-p.; Cai, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Yang, J.; et al. Influence of meteorological conditions on PM2.5 concentrations across China: A review of methodology and mechanism. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.; Guo, Q.; He, Z.; Feng, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Spatiotemporal Trends and Drivers of PM2.5 Concentrations in Shandong Province from 2014 to 2023 Under Socioeconomic Transition. Toxics 2025, 13, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, C.H.; Portocarrero, M.N.L.; Salas, R.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, P.C.; López-Gonzales, J.L. Air quality assessment and pollution forecasting using artificial neural networks in Metropolitan Lima—Peru. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, L.; Cai, C.; Zhao, Y. Multi-step ozone concentration prediction model based on improved secondary decomposition and adaptive kernel density estimation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xun, L.; Li, T.; Yan, Q. TISE-LSTM: A LSTM model for precipitation nowcasting with temporal interactions and spatial extract blocks. Neurocomputing 2024, 590, 127700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, M.; Wang, P.; Gao, Z. A Method Based on Deep Learning for Severe Convective Weather Forecast: CNN-BiLSTM-AM (Version 1.0). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Li, M.-Z.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, R. MGAtt-LSTM: A multi-scale spatial correlation prediction model of PM2.5 concentration based on multi-graph attention. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 179, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, G.; Hopke, P.K.; Yazdani, M. Forecasting PM2.5 concentration using artificial neural network and its health effects in Ahvaz, Iran. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xiong, S.; Wang, L.; Bao, C. Improved prediction model for daily PM2.5 concentrations with particle swarm optimization and BP neural network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Hoi, H.; Park, I.; Oh, H.-R.; Gim, H.-J.; Hur, S.-K.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.-R. Development of a PM2.5 prediction model using a recurrent neural network algorithm for the Seoul metropolitan area, Republic of Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 245, 118021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulqarnain, M.; Ghazali, R.; Shah, H.; Ismail, L.H.; Alsheddy, A.; Mahmud, M. A Deep Two-State Gated Recurrent Unit for Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Concentration Forecasting. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 71, 3051–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawi, O.A.; Kamar, H.M.; Alsuwaiyan, A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Temporal trends and predictive modeling of air pollutants in Delhi: A comparative study of artificial intelligence models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaraman, S.; Pachaivannan, P.; Elamparithi, P.N.; Manimozhi, S. Application of LSTM models in predicting particulate matter (PM2.5) levels for urban area. J. Eng. Res. 2022, 10, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, S.; Yu, M.; Liang, Q.; Cao, M.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Predicting indoor PM2.5 levels in shared office using LSTM method. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Tang, S.; Ren, Y.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, K. Estimation of daily ground-level PM2.5 concentrations over the Pearl River Delta using 1 km resolution MODIS AOD based on multi-feature BiLSTM. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 290, 119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnati, H.; Soma, A.; Alam, A.; Kalaavathi, B. Comprehensive analysis of various imputation and forecasting models for predicting PM2.5 pollutant in Delhi. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 11441–11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, W. Multi-dimensional distribution prediction of PM2.5 concentration in urban residential areas based on CNN. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, K.; Bao, S.; Cui, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ge, C.; Zhang, Y. Estimating the spatiotemporal distribution of PM2.5 concentrations in Tianjin during the Chinese Spring Festival: Impact of fireworks ban. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 361, 124899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zuo, X.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Huang, B. A systematic review for transformer-based long-term series forecasting. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S. Modeling air quality PM2.5 forecasting using deep sparse attention-based transformer networks. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 13535–13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Sun, H. Prediction of PM2.5 concentration based on the weighted RF-LSTM model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 3023–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Xu, N. Daily PM2.5 concentration prediction based on variational modal decomposition and deep learning for multi-site temporal and spatial fusion of meteorological factors. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranolo, A.; Zhou, X.; Mao, Y. A novel bifold-attention-LSTM for analyzing PM2.5 concentration-based multi-station data time series. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 3337–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xie, J. Investigation of nearby monitoring station for hourly PM2.5 forecasting using parallel multi-input 1D-CNN-biLSTM. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Xing, M.; Wu, W.; Jiang, F.; Guo, X.; Han, Q.; et al. SHAP explainable PSO-CNN-BiLSTM for 6-hour prediction analysis of urban PM2.5 and O3 concentrations. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, V. Multi-view Stacked CNN-BiLSTM (MvS CNN-BiLSTM) for urban PM2.5 concentration prediction of India’s polluted cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Mai, W.; Zhang, C.; Wan, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, M. A hybrid CLSTM-GPR model for forecasting particulate matter (PM2.5). Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, T.; Rayalu, G.M. Enhanced PM2.5 prediction in Delhi using a novel optimized STL-CNN-BILSTM-AM hybrid model. Asian J. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Jin, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, X. Deep learning methods for atmospheric PM2.5 prediction: A comparative study of transformer and CNN-LSTM-attention. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, H. A new method for predicting PM2.5 concentrations in subway stations based on a multiscale adaptive noise reduction transformer -BiGRU model and an error correction method. J. Infrastruct. Intell. Resil. 2025, 4, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z.; He, H.-D.; Huang, H.-C.; Yang, J.-M.; Peng, Z.-R. High-resolution spatiotemporal prediction of PM2.5 concentration based on mobile monitoring and deep learning. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 364, 125342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakouti, S.M. From accurate to actionable: Interpretable PM2.5 forecasting with feature engineering and SHAP for the Liverpool–Wirral region. Environ. Chall. 2025, 21, 101290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Yang, J.; Niu, B. Simulation and prediction of PM2.5 concentrations and analysis of driving factors using interpretable tree-based models in Shanghai, China. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshraftar, Z. Modeling of CO2 solubility and partial pressure in blended diisopropanolamine and 2-amino-2-methylpropanol solutions via response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, M.; Okkonen, J.; Suutala, J. Snow water equivalent forecasting in sub-arctic and arctic regions: Efficient recurrent neural networks approach. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 194, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, X.; Jia, C.; Li, S.; Tian, J.; Zhou, W.; Wu, C. Unified CNN-LSTM for keyhole status prediction in PAW based on spatial-temporal features. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhao, H.; Chi, Y. A comprehensive evaluation of deep learning approaches for ground-level ozone prediction across different regions. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 86, 103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussan, U.; Wang, H.; Peng, J.; Jiang, H.; Rasheed, H. Transformer-based renewable energy forecasting: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvita, M.J.; Zulu, N.G.; Thethwayo, B. Artificial neural network integrated SHapley Additive exPlanations modeling for sodium dichromate formation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Chowdhury, I.R. Towards cleaner air in Siliguri: A comprehensive study of PM2.5 and PM10 through advance computational forecasting models for effective environmental interventions. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, J.; Petrosian, O. Long-Term Forecasting of Air Pollution Particulate Matter (PM2.5) and Analysis of Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Ahmad, K. Data-driven predictive modeling of PM2.5 concentrations using machine learning and deep learning techniques: A case study of Delhi, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 195, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Qin, C.; Li, Z.; Li, K. Spatiotemporal variations of PM2.5 pollution and its dynamic relationships with meteorological conditions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, C.; Cheng, T.; Gu, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Bao, F. Contribution of meteorological factors to particulate pollution during winters in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, G.; Wang, S.; Yim, S.H.L.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Shang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Impact of low-pressure systems on winter heavy air pollution in the northwest Sichuan Basin, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 13601–13615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Di, Z.; Chang, M.; Zheng, J.; Tanaka, T.; Kuroi, K. Study on the influencing factors on indoor PM2.5 of office buildings in beijing based on statistical and machine learning methods. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangeli, C.; Palermi, S.; Bianco, S.; Aruffo, E.; Chiacchiaretta, P.; Di Carlo, P. The Relationship between PM2.5 and PM10 in Central Italy: Application of Machine Learning Model to Segregate Anthropogenic from Natural Sources. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metya, A.; Dagupta, P.; Halder, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Tiwari, Y.K. COVID-19 Lockdowns Improve Air Quality in the South-East Asian Regions, as Seen by the Remote Sensing Satellites. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 1772–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ge, Q. The positive impact of the Omicron pandemic lockdown on air quality and human health in cities around Shanghai. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 8791–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Guan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, D.; Wang, S. Regional demarcation of synergistic control for PM2.5 and ozone pollution in China based on long-term and massive data mining. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Influence Factor | Abbreviation | R |

|---|---|---|

| PM10 | PM10 | 0.8995 |

| SO2 | SO2 | 0.6110 |

| CO | CO | 0.7074 |

| NO2 | NO2 | 0.6692 |

| O3 | O3 | −0.1478 |

| precipitation | P | −0.1423 |

| mean atmospheric pressure | MAP | 0.2893 |

| extreme wind velocity | EWV | −0.1459 |

| mean atmospheric temperature | MAT | −0.3860 |

| mean wind velocity | MWV | −0.0963 |

| mean relative humidity | MRH | −0.0597 |

| mean water pressure | MWP | −0.3591 |

| minimum AP | MINAP | 0.2909 |

| sunshine hours | SH | −0.1180 |

| maximum AP | MAXAP | 0.2927 |

| minimum AT | MINAT | −0.3934 |

| maximum WV | MAXWV | −0.0953 |

| maximum AT | MAXAT | −0.3672 |

| minimum RH | MINRH | −0.1139 |

| Hyperparameters | ANN | RNN | BiLSTM | CNN | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units in HL | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| Activation function | Logsig-purelin | Tanh-sigmoid | Tanh-sigmoid | Relu | Gelu |

| Learning rate | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Epochs | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Optimizer | Trainbr | Adam | Adam | Adam | Adam |

| Kernel size | 3 | ||||

| Max-pooling | 2 | ||||

| Convolution filters | 64-96 |

| Models | R | RMSE (μg/m3) | MAE (μg/m3) | MAPE (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| RNN | 0.9612 | 0.9544 | 0.9674 | 11.9428 | 10.8593 | 6.3036 | 8.1027 | 7.5617 | 4.6586 | 25.4569 | 21.8824 | 34.2459 |

| ANN | 0.9617 | 0.9629 | 0.9680 | 11.8627 | 10.2998 | 6.2723 | 8.0425 | 7.3455 | 4.6529 | 24.7668 | 21.5320 | 33.4613 |

| BiLSTM | 0.9627 | 0.9661 | 0.9709 | 11.3422 | 9.8537 | 6.1696 | 7.6274 | 7.0621 | 4.6414 | 23.6251 | 20.9814 | 32.3479 |

| CNN | 0.9638 | 0.9677 | 0.9711 | 10.8414 | 9.0371 | 5.9106 | 7.4928 | 6.4172 | 4.5856 | 22.8975 | 20.9579 | 31.5879 |

| Transformer | 0.9655 | 0.9684 | 0.9712 | 10.4600 | 8.1992 | 5.6769 | 7.0681 | 5.6803 | 4.4915 | 21.1830 | 19.1756 | 31.3887 |

| CNN–BiLSTM–Transformer | 0.9832 | 0.9687 | 0.9743 | 6.5734 | 8.1896 | 5.4236 | 4.6801 | 5.6748 | 4.0220 | 20.2955 | 18.1750 | 22.7791 |

| Embedding Dimension | Number of Heads | Encoder Layers | R | RMSE (μg/m3) | MAE (μg/m3) | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 4 | 2 | 0.9684 | 8.7654 | 6.2082 | 24.3989 |

| 64 | 4 | 3 | 0.9633 | 9.3897 | 6.4147 | 24.1623 |

| 64 | 4 | 4 | 0.9629 | 9.3456 | 6.3296 | 24.3151 |

| 64 | 8 | 2 | 0.9680 | 8.6745 | 6.1392 | 24.4983 |

| 64 | 8 | 3 | 0.9670 | 9.5390 | 6.7693 | 24.2755 |

| 64 | 8 | 4 | 0.9640 | 9.1835 | 6.6503 | 24.9770 |

| 64 | 16 | 2 | 0.9662 | 8.8925 | 6.2809 | 24.7377 |

| 64 | 16 | 3 | 0.9620 | 9.1232 | 6.2082 | 24.8126 |

| 64 | 16 | 4 | 0.9682 | 8.8714 | 6.3670 | 24.9837 |

| 128 | 4 | 2 | 0.9704 | 8.4533 | 5.7435 | 23.7833 |

| 128 | 4 | 3 | 0.9730 | 7.8222 | 5.4710 | 23.7285 |

| 128 | 4 | 4 | 0.9656 | 8.8593 | 6.1632 | 23.8092 |

| 128 | 8 | 2 | 0.9681 | 8.4701 | 6.0639 | 23.3543 |

| 128 | 8 | 3 | 0.9743 | 5.4236 | 4.0220 | 22.7791 |

| 128 | 8 | 4 | 0.9665 | 8.4009 | 5.4240 | 23.3543 |

| 128 | 16 | 2 | 0.9689 | 8.4177 | 6.0283 | 23.6519 |

| 128 | 16 | 3 | 0.9725 | 7.9030 | 5.5623 | 23.9408 |

| 128 | 16 | 4 | 0.9705 | 8.1568 | 5.6960 | 23.0055 |

| 256 | 4 | 2 | 0.9677 | 8.2928 | 5.9024 | 23.6324 |

| 256 | 4 | 3 | 0.9740 | 7.5075 | 5.2639 | 23.1160 |

| 256 | 4 | 4 | 0.9742 | 7.8369 | 5.7447 | 23.8093 |

| 256 | 8 | 2 | 0.9700 | 8.4563 | 6.1401 | 23.8292 |

| 256 | 8 | 3 | 0.9710 | 8.4114 | 5.8592 | 23.8874 |

| 256 | 8 | 4 | 0.9703 | 8.1029 | 5.7008 | 23.7381 |

| 256 | 16 | 2 | 0.9730 | 8.3425 | 5.9998 | 23.6920 |

| 256 | 16 | 3 | 0.9677 | 8.2103 | 5.4124 | 23.0151 |

| 256 | 16 | 4 | 0.9709 | 8.1570 | 5.7105 | 23.7410 |

| Subset | R | RMSE (μg/m3) | MAE (μg/m3) | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall test set | 0.9743 | 5.4236 | 4.0220 | 22.7791 |

| High PM2.5 events | 0.9621 | 9.8215 | 8.5923 | 11.5314 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, G.; Qiao, S.; Wang, Z. Forecasting Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Qingdao City Using Deep Learning and Hybrid Interpretable Models and Analysis of Driving Factors Using SHAP. Toxics 2026, 14, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010044

He Z, Guo Q, Zhang Z, Feng G, Qiao S, Wang Z. Forecasting Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Qingdao City Using Deep Learning and Hybrid Interpretable Models and Analysis of Driving Factors Using SHAP. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhenfang, Qingchun Guo, Zuhan Zhang, Genyue Feng, Shuaisen Qiao, and Zhaosheng Wang. 2026. "Forecasting Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Qingdao City Using Deep Learning and Hybrid Interpretable Models and Analysis of Driving Factors Using SHAP" Toxics 14, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010044

APA StyleHe, Z., Guo, Q., Zhang, Z., Feng, G., Qiao, S., & Wang, Z. (2026). Forecasting Daily Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Qingdao City Using Deep Learning and Hybrid Interpretable Models and Analysis of Driving Factors Using SHAP. Toxics, 14(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010044