Protective Effects of Olea europaea L. Leaves and Equisetum arvense L. Extracts Against Testicular Toxicity Induced by Metronidazole Through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Regulating NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Signaling Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Extract Preparation

2.4. Sample Preparation for Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-ESI–QTOF-MS) Analysis

2.5. High-Resolution UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS Methodology

2.6. Mass Spectrometric Conditions

2.7. Data Processing and Metabolite Identification

2.8. Animals and Experimental Design

2.9. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.10. Sperm Evaluation

2.11. Serum Testosterone

2.12. Oxidative Stress

2.13. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis of NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Genes

2.14. Histopathological Examination

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Plant Metabolites

3.2. The Characteristic Metabolites of Olive Leaf Extract

3.3. The Characteristic Profile of Horsetail Extract

3.4. Shared Metabolites and Their Significance

3.5. Sperm Evaluation

3.6. Serum Testosterone

3.7. Oxidative Stress

3.8. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis of NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Genes

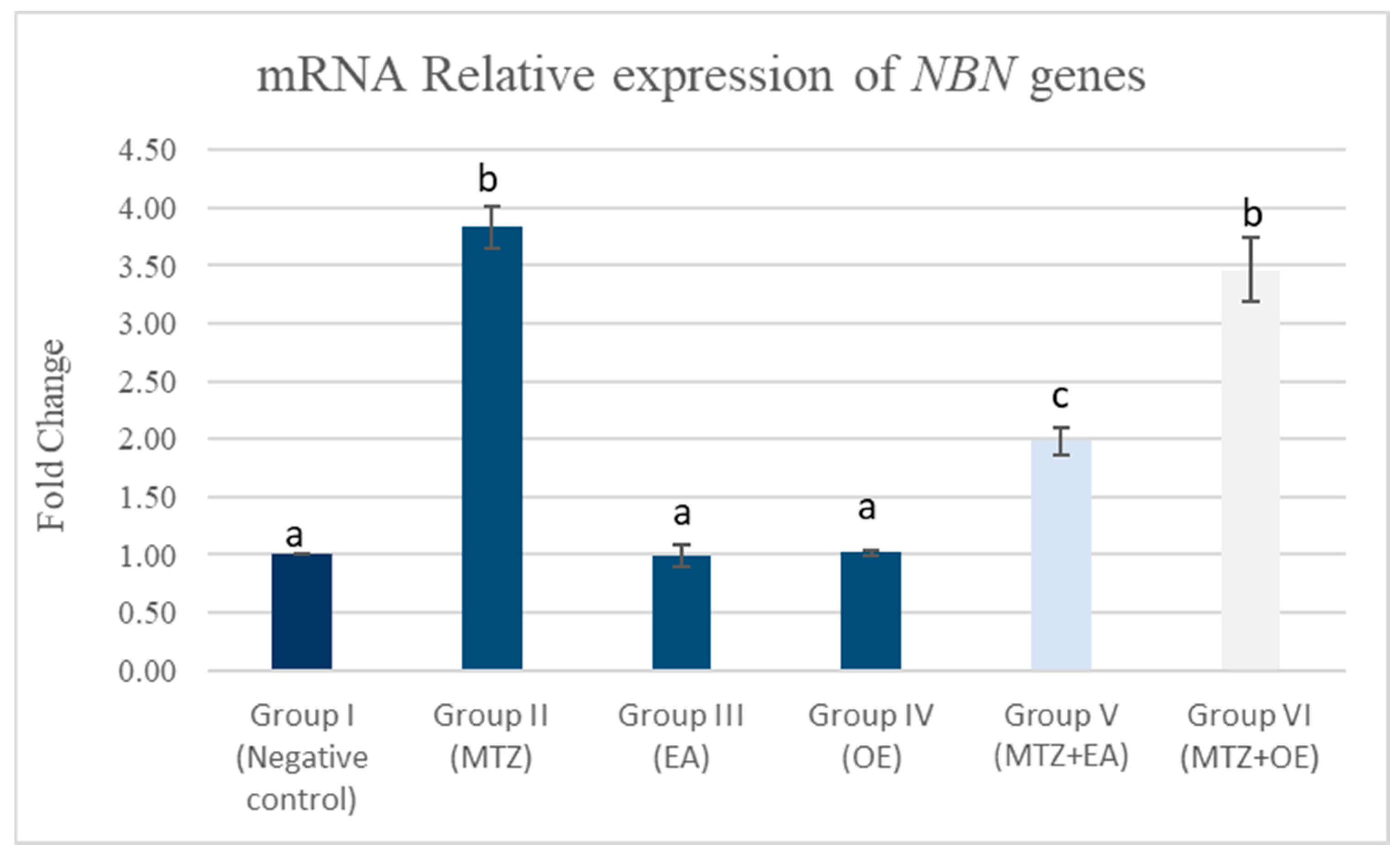

3.8.1. Testicular mRNA Relative Expression of NBN Gene

3.8.2. Testicular mRNA Relative Expression of INSL-3 Genes

3.8.3. Testicular mRNA Relative Expression of STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Genes

3.9. Histopathology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domínguez-Vías, G.; Segarra, A.B.; Ramírez-Sánchez, M.; Prieto, I. Olive oil and male fertility. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, P. Study on the reproductive organs and fertility of the male mice following administration of metronidazole. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 7, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Mudry, M.D.; Palermo, A.M.; Merani, M.S.; Carballo, M.A. Metronidazole-induced alterations in murine spermatozoa morphology. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fararjeh, M.; Mohammad, M.K.; Bustanji, Y.; AlKhatib, H.; Abdalla, S. Evaluation of immunosuppression induced by metronidazole in Balb/c mice and human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2008, 8, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, S.S. Histopathological and biochemical alterations of metronidazole-induced toxicity in male rats. Glob. Vet. 2012, 9, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Abd, H.H.; Ahmed, H.A.; Mutar, T.F. Moringa oleifera leaves extract modulates toxicity, sperms alterations, oxidative stress, and testicular damage induced by tramadol in male rats. Toxicol. Res. 2020, 9, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón-Manzano, E.; Garrido-Cardenas, J.A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Worldwide Research Trends on Medicinal Plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamagaju, L.; Morandini, R.; Bizuru, E.; Nyetera, P.; Nduwayezu, J.B.; St’evigny, C.; Ghanem, G.; Duez, P. Tyrosinase modulation by five Rwandese herbal medicines traditionally used for skin treatment. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Manual for Early Implementation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luanda, A.; Ripanda, A.; Sahini, M.G.; Makangara, J.J. Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological study of Ocimum americanum L.: A review. Phytomed. Plus 2023, 3, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luanda, A.; Ripanda, A. Recent trend on Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Codd (Lamiaceae) for management of medical conditions. Phytomed. Plus 2023, 3, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtenga, D.V.; Ripanda, A.S. A review on the potential of underutilized Blackjack (Biden pilosa) naturally occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patova, O.A.; Luanda, A.; Paderin, N.M.; Popov, S.V.; Makangara, J.J.; Kuznetsov, S.P.; Kalmykova, E.N. Xylogalacturonan-enriched pectin from the fruit pulp of Adansonia digitata: Structural characterization and antidepressant-like effect. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, B.B.L.; Ripanda, A.S.; Mwanga, H.M. Ethnomedicinal, phytochemistry and antiviral potential of turmeric (Curcuma longa). Compounds 2022, 2, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, T.A.; Al-Abbadi, H.A.; Qahwaji, D.; Al-Ghamdi, A.K.; Shelat, V.G.; Sobhy, H.M.; Abu Hilal, M. Ameliorating effect of olive oil on fertility of male rats fed on genetically modified soya bean. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 27758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakeer, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; Khalil, K. Effects of pomegranate peel and olive pomace supplementation on reproduction and oxidative status of rabbit doe. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 106, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xia, B.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, Z. Assessment of the anti-inflammatory, analgesic and sedative effects of oleuropein from Olea europaea L. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 65, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugomaa, A.; Elbadawy, M. Olive leaf extract modulates glycerolinduced kidney and liver damage in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22100–22111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbishegi, M.; Gorgich, E.A.C.; Khajavi, O. Olive leaves extract improved sperm quality and antioxidant status in the testis of rat exposed to rotenone. Nephro.-Urol. Mon. 2017, 9, e47127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeer, R.S.; Abdel Moneim, A.E. Evaluation of the protective effect of olive leaf extract on cisplatin-induced testicular damage in rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8487248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Zahedi, S.M. Reproductive behavior and water use efficiency of olive trees (Olea europaea L. cv Konservolia) under deficit irrigation and mulching. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2019, 61, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, G.A.; Saeedan, A.S.; Abdel-Rahman, R.F.; Ogaly, H.A.; Abd-Elsalam, R.M.; Abdel-Kader, M.S. Olive leaves extract attenuates type II diabetes mellitus-induced testicular damage in rats: Molecular and biochemical study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badole, S.; Kotwal, S. Equisetum arvense: Ethanopharmacological and phytochemical review with reference to osteoporosis single enzyme nanoparticles for application in humification and carbon sequestration process view project phytotherapeutics view project. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Health Care 2014, 1, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V.; Marín, S. Effect of Equisetum arvense and Stevia rebaudiana extracts on growth and mycotoxin production by Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides in maize seeds as affected by water activity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masłowski, M.; Miedzianowska, J.; Czylkowska, A.; Strzelec, K. Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) as a functional filler for natural rubber biocomposites. Materials 2020, 13, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, C. Biology and functional ecology of equisetum with emphasis on the giant horsetails. Bot. Rev. 2013, 79, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahem, E.S.; Mohamed, G.H.; El-Gazar, A.F. Therapeutic effect of Equisetum arvense L. on bone and scale biomarkers in female rats with induced osteoporosis. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, T.; Tafarelo Moreno, K.G.; Gasparotto, A., Jr.; da Silva, L.M.; de Souza, P. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of the genus Equisetum (Equisetaceae): A narrative review of the species with therapeutic potential for kidney diseases. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6658434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.A.H.; Erzaiq, Z.S.; Khalaf, T.M.; Mustafa, M.A. Effect of Equisetum arvense phenolic extract in treatment of Entamoeba histolytica infection. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 618–620. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, R.; Pasko, P.; Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Szewczyk, A.; Szlosarczyk, M.; Isabel, S.C. Antibacterial, antioxidant and antiproliferative properties and zinc content of five south Portugal herbs. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajri, M.; Ahmadi, A.; Sadrkhanlou, R. Protective effects of Equisetum arvense methanolic extract on sperm characteristics and in vitro fertilization potential in experimental diabetic mice: An experimental study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2020, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patova, O.A.; Smirnov, V.V.; Golovchenko, V.V.; Vityazev, F.V.; Shashkov, A.S.; Popov, S.V. Structural, rheological and antioxidant properties of pectins from Equisetum arvense L. and Equisetum sylvaticum L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 1, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukric, Z.; Topali’c-Trivunovi’c, L.; Pavicic, S.; Zabic, M.; Matos, S.; Davidovic, A. Total phenolic content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Equisetum arvense L. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallag, A.; Filip, G.A.; Olteanu, D.; Clichici, S.; Baldea, I.; Jurca, T.; Micle, O.; Vicas, L.; Marian, E.; Soritau, O.; et al. Equisetum arvense L. Extract induces antibacterial activity and modulates oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in endothelial vascular cells exposed to hyperosmotic stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3060525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Monte, F.H.; dos Santos, J.G., Jr.; Russi, M.; Lanziotti, V.M.; Leal, L.K.; Cunha, G.M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of the hydroalcoholic extract of stems from Equisetum arvense L. in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 49, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, N.S.; Kaur, S.; Chopra, D. Equietum arvense: Pharmacology and phytochemistry—A review. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2010, 3, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, J.G., Jr.; Blanco, M.M.; Do Monte, F.H.; Russi, M.; Lanziotti, V.M.; Leal, L.K.; Cunha, G.M. Sedative and anticonvulsant effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetojevic-Simin, D.D.; Canadanovic-Brunet, J.M.; Bogdanovic, G.M.; Djilas, S.M.; Cetkovic, G.S.; Tumbas, V.T.; Stojiljkovic, B.T. Antioxidative and antiproliferative activities of different horsetail (Equisetum arvense L.) extracts. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashed, M.S.; Hassanen, E.I.; Issa, M.Y.; Tohamy, A.F.; Prince, A.M.; Hussien, A.M.; Soliman, M.M. The mollifying effect of Sambucus nigra extract on StAR gene expression, oxidative stress, and apoptosis induced by fenpropathrin in male rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 189, 114744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, M.M.; Nashed, M.S.; Hassanen, E.I.; YIssa, M.Y.; Prince, A.M.; Hussien, A.M.; Tohamy, A.F. Ameliorative effects of date palm kernel extract against fenpropathrin induced male reproductive toxicity. Biol. Res. 2025, 58, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, S.; Madhuri, D.; Lakshman, M.; Reddy, A.G. Epididymal semen analysis in testicular toxicity of doxorubicin in male albino Wistar rats and its amelioration with quercetin. Pharma Innov. J. 2018, 7, 555–558. [Google Scholar]

- Hozyen, H.F.; Khalil, H.M.A.; Ghandour, R.A.; Al-Mokaddem, A.K.; Amer, M.S.; Azouz, R.A. Nano selenium protects against deltamethrin-induced reproductive toxicity in male rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 408, 115274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutler, E.; Duron, O.; Kelly, B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963, 61, 882–888. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, D.R.; Martinez, P.G.; Michel, X.; Narbonne, J.F.; O’hara, S.; Ribera, D.; Winston, G.W. Oxyradical production as a pollution-mediated mechanism of toxicity in the common mussel, Mytilus edulis L., and other molluscs. Funct. Ecol. 1990, 4, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, M.M.; Galal, M.K.; El-Behairy, A.M.; Gouda, E.M.; Moussa, S.Z. Maternal exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate induces alterations of c-Myc gene, some apoptotic and growth related genes in pups’ testes. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2018, 34, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.H.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Rashad, M.M.; MYoussef, A.; Galal, M.K.; Bashir, D.W. Screening for polystyrene nanoparticle toxicity on kidneys of adult male albino rats using histopathological, biochemical, and molecular examination results. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 388, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.A.E.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Ahmed, Z.S.O.; Galal, M.K.; Rashad, M.M.; Youssef, A.M.; Elleithy, E.M.M. Exposure to Polystyrene nanoparticles induces liver damage in rat via induction of oxidative stress and hepatocyte apoptosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 94, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, A.R.; Bashir, D.W.; Yasin, N.A.E.; Rashad, M.M.; El-Gharbawy, S.M. Ameliorative effect of N-acetylcysteine on the testicular tissue of adult male albino rats after glyphosate-based herbicide exposure. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e22997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuzaied, H.; Bashir, D.W.; Rashad, E.; Rashad, M.M.; El-Habback, H. Counteracting titanium dioxide nanoparticle hepatotoxicity with ginseng: Modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in a rat model. Environ. Eng. Res. 2026, 31, 250278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghafar, N.S.; Hamed, R.I.; El-Saied, E.M.; Rashad, M.M.; Yasin, N.A.; Noshy, P.A. Protective effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles against liver and kidney toxicity induced by oxymetholone, a steroid doping agent: Modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and gene expression in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 505, 117574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesham, A.; Abass, M.; Abdou, H.; Fahmy, R.; Rashad, M.M.; Abdallah, A.A.; Mossallem, W.; Rehan, I.F.; Elnagar, A.; Zigo, F.; et al. Ozonated saline intradermal injection: Promising therapy for accelerated cutaneous wound healing in diabetic rats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1283679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakeer, M.R.; Rashad, M.M.; Youssef, F.S.; Ahmed, O.; Soliman, S.S.; Ali, G.E. Ameliorative effect of curcumin loaded Nanoliposomes, A Promising bioactive formulation, against the DBP-induced testicular damage. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025, 137, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, M.A.; El-Bestawy, E.A.; El-Nakieb, F.; Hassan, S.M.; Hafez, E.E. Arsenate phytoremediation-linked genes in Egyptian rice cultivars as soil pollution DNA geno-sensor. Biosci. Res. 2018, 15, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.; Rashad, M.; Elleithy, E.; Sabry, Z.; Ali, G.; Elmosalamy, S. L-Carnitine alleviates hepatic and renal mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic progression induced by letrozole in female rats through modulation of Nrf-2, Cyt c and CASP-3 signaling. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 46, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, R.L.A.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Abdel-Razik, A.H.; Kamel, S.; Farghali, A.A.; Saleh, R.; Mahmoud, R.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Nabil, T.M.; El-Ela, F.I.A. Physiological roles of propolis and red ginseng nanoplatforms in alleviating dexamethasone-induced male reproductive challenges in a rat model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.E.; El Badawy, S.A.; Elmosalamy, S.H.; Emam, S.R.; Azouz, A.A.; Galal, M.K.; Hassan, B.B. Novel promising reproductive and metabolic effects of Cicer arietinum L. extract on letrozole induced polycystic ovary syndrome in rat model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmosalamy, S.H.; Elleithy, E.M.; Ahmed, Z.S.O.; Rashad, M.M.; Ali, G.E.; Hassan, N.H. Dysregulation of intraovarian redox status and steroidogenesis pathway in letrozole-induced PCOS rat model: A possible modulatory role of l-Carnitine. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theories and Practice of Histological Techniques; Churchil Livingstone: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 7, pp. 2768–2773. [Google Scholar]

- Hosny, Y.; Khalifa, M.H.; Azouz, R.A.; Ismail, M.A.; Moustafa, M.; Salem, M.A.; Korany, R.M.S. Effects of Propylparaben exposure on male reproductive function and fertility in CD-1 mice. J. Basic Appl. Zool 2025, 86, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründemann, C.; Lengen, K.; Sauer, B.; Garcia-Käufer, M.; Zehl, M.; Huber, R. Equisetum arvense (common horsetail) modulates the function of inflammatory immunocompetent cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-García, I.; Olmo-García, L.; Polo-Megías, D.; Serrano, A.; León, L.; de la Rosa, R.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Fruit Phenolic and Triterpenic Composition of Progenies of Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata, an Interesting Phytochemical Source to Be Included in Olive Breeding Programs. Plants 2022, 11, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toumi, K.; Świątek, Ł.; Boguszewska, A.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Bouaziz, M. Comprehensive Metabolite Profiling of Chemlali Olive Tree Root Extracts Using LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS, Their Cytotoxicity, and Antiviral Assessment. Molecules 2023, 28, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aloy, M.; Groff, N.; Masuero, D.; Nisi, M.; Franco, A.; Battelini, F.; Vrhovsek, U.; Mattivi, F. Exploratory Analysis of Commercial Olive-Based Dietary Supplements Using Untargeted and Targeted Metabolomics. Metabolites 2020, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazafroudi, N.K.; Mailänder, L.K.; Daniels, R.; Kammerer, D.R.; Stintzing, F.C. From Stem to Spectrum: Phytochemical Characterization of Five Equisetum Species and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbattista, R.; Ventura, G.; Calvano, C.D.; Cataldi, T.R.I.; Losito, I. Bioactive Compounds in Waste By-Products from Olive Oil Production: Applications and Structural Characterization by Mass Spectrometry Techniques. Foods 2021, 10, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayek, N.M.; Farag, M.A.; Saber, F.R. Metabolome classification via GC/MS and UHPLC/MS of olive fruit varieties grown in Egypt reveal pickling process impact on their composition. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, T.; Khlif, I.; Kanakis, P.; Termentzi, A.; Allouche, N.; Halabalaki, M.; Skaltsounis, A.L. UHPLC-DAD-FLD and UHPLC-HRMS/MS based metabolic profiling and characterization of different Olea europaea organs of Koroneiki and Chetoui varieties. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, E.; Ezzat, M.I.; Sallam, I.E.; Zaafar, D.; Gawish, A.Y.; Ahmed, Y.H.; Elghandour, A.H.; Issa, M.Y. Impact of thermal processing on phytochemical profile and cardiovascular protection of Beta vulgaris L. in hyperlipidemic rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. Analysis of phenolic compounds in leaves from endemic trees from Madeira Island. A contribution to the chemotaxonomy of Laurisilva forest species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 64, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kanakis, P.; Termentzi, A.; Michel, T.; Gikas, E.; Halabalaki, M.; Skaltsounis, A.L. From olive drupes to olive oil. An HPLC-orbitrap-based qualitative and quantitative exploration of olive key metabolites. Planta Medica 2013, 79, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbash, E.M.; Abdel-Shakour, Z.T.; El-Ahmady, S.H.; Wink, M.; Ayoub, I.M. Comparative metabolic profiling of olive leaf extracts from twelve different cultivars collected in both fruiting and flowering seasons. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralbo-Molina, Á.; Priego-Capote, F.; de Castro, M.D.L. Tentative identification of phenolic compounds in olive pomace extracts using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with a quadrupole-quadrupole-time-of-flight mass detector. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11542–11550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Yu, H.S.; Ra, M.J.; Jung, S.M.; Yu, J.N.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, K.H. Phytochemical Investigation of Equisetum arvense and Evaluation of Their Anti-Inflammatory Potential in TNFα/INFγ-Stimulated Keratinocytes. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritikou, E.; Kalogiouri, N.P.; Kolyvira, L.; Thomaidis, N.S. Target and Suspect HRMS Metabolomics for the Determination of Functional Ingredients in 13 Varieties of Olive Leaves and Drupes from Greece. Molecules 2020, 25, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Męczarska, K.; Cyboran-Mikołajczyk, S.; Solarska-Ściuk, K.; Oszmiański, J.; Siejak, K.; Bonarska-Kujawa, D. Protective Effect of Field Horsetail Polyphenolic Extract on Erythrocytes and Their Membranes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, L.; Uccella, N.A.; Sivakumar, G. Soft-MS and computational mapping of oleuropein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielin, E.M.; Bresciani, L.F.; Danielski, L.; Yunes, R.A.; Ferreira, S.R. Composition profile of horsetail (Equisetum giganteum L.) oleoresin: Comparing SFE and organic solvents extraction. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2005, 33, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, R.H. Effect of metronidazole, ipronidazole, and dibromochloropropane on rabbit and human sperm motility and fertility. Reprod. Toxicol. 2002, 16, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, J.K.; Vats, V.; Srinivas, M.; Das, S.N.; Gupta, D.K.; Mitra, D.K. Effect of metronidazole on spermatogenesis and FSH, LH and testosterone levels of pre-puberal rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 39, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S.R.; Bishop, Y.; Epstein, S.S. Chemical agents affecting testicular function and male fertility. In The Testis; Johnson, W.R., Gomes, W.R., van Demark, N.H., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 605–627. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R.L.; Lee, I.P. Possible role of the blood-testis barrier in dominant lethal testing. Environ. Health Perspect. 1977, 6, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Plumb, D.C. Metronidazole. In Veterinary Drug Handbook, 3rd ed.; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1999; pp. 424–425. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ashmawy, I.M. Effect of Some Drugs on Male Fertility in the Rat. Master’s Thesis, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.J.; Rahman, M.S.; Pang, W.K.; Ryu, D.Y.; Kim, B.; Pang, M.G. Bisphenol A affects the maturation and fertilization competence of spermatozoa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkakarimi, M.H.; Solgi, E.; Hosseinzadeh Colagar, A. Subcellular partitioning of cadmium and lead in Eisenia fetida and their effects to sperm count, morphology and apoptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Yang, X.; Gong, J.; Lv, J.; Yuan, X.; Shi, M.; Fu, C.; Tan, B.; Fan, Z.; Chen, L.; et al. Patterns of alteration in boar semen quality from 9 to 37 months old and improvement by protocatechuic acid. J. Animal Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gao, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Wu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. Age-related endoplasmic reticulum stress represses testosterone synthesis via attenuation of the circadian clock in leydig cells. Theriogenology 2022, 189, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.H.; Li, X.H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sun, S.C. Exposure to PBDE47 affects mouse oocyte quality via mitochondria dysfunction-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 198, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Prabakaran, S.; Allamaneni, S. What an andrologist/urologist should know about free radicals and why. Urology 2006, 67, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Mann, T.; Sherins, R. Peroxidative breakdown of phospholipids in human spermatozoa, spermicidal properties of fatty acid peroxides, and protective action of seminal plasma. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 31, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lamirande, E.; Jiang, H.; Zini, A.; Kodama, H.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species and sperm physiology. Rev. Reprod. 1997, 2, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.H.; Chao, H.T.; Chen, H.W.; Hwang, T.I.S.; Liao, T.L.; Wei, Y.H. Increase of oxidative stress in human sperm with lower motility. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Baker, M.A.; Sawyer, D. Oxidative stress in the male germ line and its role in the aetiology of male infertility and genetic disease. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2003, 7, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, L.M.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 21, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, V.; Singh, M.; Rawat, J.K.; Devi, U.; Yadav, R.K.; Roy, S.; Gautam, S.; Saraf, S.A.; Kumar, V.; Ansari, N. Redefining the role of peripheral LPS as a neuroinflammatory agent and evaluating the role of hydrogen sulphide through metformin intervention. Inflammopharmacology 2016, 24, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.M.A.; Azouz, R.A.; Hozyen, H.F.; Aljuaydi, S.H.; AbuBakr, H.O.; Emam, S.R.; Al-Mokaddem, A.K. Selenium nanoparticles impart robust neuroprotection against deltamethrin-induced neurotoxicity in male rats by reversing behavioral alterations, oxidative damage, apoptosis, and neuronal loss. NeuroToxicology 2022, 91, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattab, M.S.; Osman, A.H.; AbuBakr, H.O.; Azouz, R.A.; Ramadan, E.S.; Farag, H.S.; Ali, A.M. Bovine papillomatosis: A serological, hematobiochemical, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical investigation in cattle. Pak. Vet. J. 2023, 43, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Azouz, R.A.; AbuBakr, H.O.; Khattab, M.S.; Abou-Zeid, S.M. Buprofezin toxication implicates health hazards in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhaoui, N.; Taamalli, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Phenolic compounds in olive leaves: Analytical determination, biotic and abiotic influence, and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudache, M.; Colon, M.; Nerín, C.; Zaidi, F. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of olive by-products and antioxidant film containing olive leaf extract. Food Chem. 2016, 212, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alirezaei, M.; Kheradmand, A.; Heydari, R.; Tanideh, N.; Neamati, S.; Rashidipour, M. Oleuropein protects against ethanol-induced oxidative stress and modulates sperm quality in the rat testis. Med. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 5, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Najafizadeh, P.; Dehghani, F.; Panjeh Shahin, M.; Hamzei Taj, S. The effect of a hydro-alcoholic extract of olive fruit on reproductive argons in male sprague-dawley rat. Iran J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 11, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alahmadi, A.A.; Abduljawad, E.A. Equisetum arvense L. Extract Ameliorates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Testicular Injury Induced by Methotrexate in Male Rats. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinborn, C.; Potterat, O.; Meyer, U.; Trittler, R.; Stadlbauer, S.; Huber, R.; Gründemann, C. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of Equisetum arvense are not solely mediated by silica. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabzadegan, N.; Moghadamnia, A.A.; Kazemi, S.; Nozari, F.; Moudi, E.; Haghanifar, S. Effect of Equisetum arvense extract on bone mineral density in Wistar rats via digital radiography. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 10, 176–218. [Google Scholar]

- Farag, M.R.; Alagawany, M.; Tufarelli, V. Testicular toxicity of metronidazole: Histopathological and biochemical evidence. Toxicol. Rep. 2012, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baligar, P.N.; Kaliwal, B.B. Reproductive toxicity of metronidazole in male rats. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5, 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.A.; Bel Hadj Salah, K.; Fahmy, E.M.; Mansour, D.A.; Mohamed, S.A.M.; Abdallah, A.A.; Ashkan, M.F.; Majrashi, K.A.; Melebary, S.J.; El-Sheikh, E.-S.A.; et al. Olive leaf extract attenuates chlorpyrifos-induced neuro-and reproductive toxicity in male albino rats. Life 2022, 12, 1500. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, M.A.; Abd-Alla, H.I.; Ahmed, H.H.; Bassem, S.M. Antioxidant potential of Equisetum arvense in mitigating reproductive toxicity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 113067. [Google Scholar]

- Bădărău, A.S.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Gille, E.; Miron, A. Flavonoid and phenolic content of Equisetum arvense L. and their contribution to the antioxidant activity. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Park, H.M.; Han, S.H. Characterization of silica accumulation and distribution in Equisetum arvense. J. Plant Res. 2023, 136, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.H.; Awadalla, E.A.; Ali, R.A.; Fouad, S.S.; Abdel-Kahaar, E. Thiamine deficiency and oxidative stress induced by prolonged metronidazole therapy can explain its side effects of neurotoxicity and infertility in experimental animals: Effect of grapefruit co-therapy. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alami, Z.M.; Shraideh, Z.A.; Taha, M.O. Rosmarinic acid reverses the effects of metronidazole-induced infertility in male albino rats. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 1910–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligha, A.E.; Bokolo, B.; Didia, B.C. Antifertility potentials of metronidazole in male Wistar rats. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 15, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, D.; Alipour, M.; Mellati, A.A. Effect of metronidazole on spermatogenesis, plasma gonadotrophins and testosterone in rats. Iran J. Reprod. Med. 2007, 15, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Monageng, E.; Offor, U.; Takalani, N.B.; Mohlala, K.; Opuwari, C.S. A Review on the Impact of Oxidative Stress and Medicinal Plants on Leydig Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Pramanik, J.; Mahata, B. Revisiting steroidogenesis and its role in immune regulation with the advanced tools and technologies. Genes. Immun. 2021, 22, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, P.R.; Dyson, M.T.; Stocco, D.M. Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression: Present and future perspectives. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshy, P.A.; Khalaf, A.A.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Mekkawy, A.M.; Abdelrahman, R.E.; Farghali, A.; Tammam, A.A.; Zaki, A.R. Alterations in reproductive parameters and steroid biosynthesis induced by nickel oxide nanoparticles in male rats: The ameliorative eFfect of hesperidin. Toxicology 2022, 473, 153208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Mo, J.; Wang, Y.; Ni, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, Q.; Ge, R.S. Endocrine disruptors of inhibiting testicular 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 303, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligha, A.E.; Paul, C.W. Oxidative effect of metronidazole on the testis of Wistar rats. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, P. Tribulus terrestris ameliorates metronidazole-induced spermatogenic inhibition and testicular oxidative stress in the laboratory mouse. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2015, 47, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashandy, M.M.; Saeed, H.E.; Ahmed, W.M.S.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Shehata, O. Cerium oxide nanoparticles attenuate the renal injury induced by cadmium chloride via improvement of the NBN and Nrf2 gene expressions in rats. Toxicol. Res. 2022, 11, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivell, R.; Heng, K.; Anand-Ivell, R. Insulin-like factor 3 and the HPG axis in the male. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, T.; Myoda, T.; Nagashima, T. Antioxidative activities of water extract and ethanol extract from field horsetail (Tsukushi) Equisetum arvense L. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, V.; Gaspar, A.; Savin, S.; Toma, A.; Tatia, R.; Gille, E. Phenolic content, antioxidant activity and effect on collagen synthesis of a traditional wound healing polyherbal formula. Studia Univ. 2015, 25, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeer, M.R.; Rashad, M.M.; Azouz, A.A.; Azouz, R.A.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Kadasah, S.F.; Shaalan, M.; Ali, A.M.; Issa, M.Y.; El-Samanoudy, S.I. Molecular, Physiological, and Histopathological Insights into the Protective Role of Equisetum arvense and Olea europaea Extracts Against Metronidazole-Induced Pancreatic Toxicity. Life 2025, 15, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola-Rabada, A.; Rinck, J.; Belton, D.J.; Powell, A.K.; Perry, C.C. Isolation of a wide range of minerals from a thermally treated plant: Equisetum arvense, a Mare’s tale. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 21, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Symbol | Gene Description | Accession Number | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBN [52] | Nibrin | NM_138873.2 | F: 5′-CTTCAGGACAGCAGTGAGGA-3′ R: 5′-TCTTTCGAGCATGGTGACCT-3′ |

| INSL-3 [53] | Insulin-like growth factor -3 | NM_053680 | F: 5′-GTGGCTGGAGCAACGACA-3′ R: 5′-AGAAGCCTGGTGAGGAAGC-3′ |

| STAR [54] | Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory | NM_031558.3 | F: 5′-GCC TGA GCA AAG CGG TGT C-3′ R: 5′-CTG GCG AAC TCT ATC TGG GTCTGT-3′ |

| HSD-3β [55] | Hydroxy-Delta5-Steroid Dehydrogenase, 3 Beta- And Steroid Delta Isomerase 1 | NM_001007719.3 | F: 5′-CTCACATGTCCTACCCAGGC-3′ R: 5′-TATTTTTGAGGGCCGCAAGT-3′ |

| CYP11A1 [56,57] | Cytochrome P450 11A1 | NM_017286.3 | F: 5′-GCT GGAAGG TGT AGC TCA GG-3′ R: 5′-CAC TGG TGT GGA ACA TCT GG-3′ |

| ACTB [45] | Actin beta | NM_031144.3 | F: 5′-TGTCACCAACTGGGACGAT-3′ R: 5′-GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAA-3′ |

| Rt | M-H | Error | Name | Molecular Formula | Fragments | Horsetail Ethanol Extract | Olive Leaf Ethanol Extract | Reference | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.05 | 133.0142 | 0.00 | Malic acid | C4H6O5 | 115,89,73,71 | + | + | [60] | Organic acid |

| 1.07 | 173.0455 | 0.00 | Shikimic acid | C7H10O5 | 155,137,129,111,93,85 | + | − | [60] | Phenolic acid |

| 1.09 | 317.0305 | 0.66 | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | 299,225,165, 81 | − | + | [61] | Flavonoids |

| 1.10 | 195.0511 | 0.38 | Gluconic acid | C6H12O7 | 177,159,129,99,87,75 | − | + | [62] | Organic acid |

| 1.11 | 165.0404 | −0.38 | Pentose acid | C5H10O6 | 147,129,105,87 | − | + | [63] | Saccharide |

| 1.11 | 179.0352 | 1.22 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 135,113,101,89,71,59 | + | − | [60] | Phenolic acid |

| 1.11 | 191.0560 | −0.59 | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 173,127,109,93,85 | − | + | [61] | Cyclitol |

| 1.12 | 295.0460 | 0.20 | Caffeoyl-malic acid | C13H12O8 | 193,179,151,133,115 | + | + | [64] | Phenolic acids |

| 1.16 | 187.0975 | −0.44 | Azelaic acid | C9H16O4 | --- | + | − | [65] | Organic acid |

| 1.17 | 279.0539 | 10.30 | Malic acid p-coumarate | C13H12O7 | 163,99 | + | − | [64] | Phenolic acids |

| 1.18 | 509.1662 | −0.49 | Demethyl ligstroside | C24H30O12 | 463,421,347,233 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.19 | 377.0855 | −6.12 | Caffeic acid derivative | C18H18O9 | 341,215,195,179,153,129 | + | + | [66] | Phenolic acids |

| 1.21 | 305.0698 | 10.24 | (Epi)gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | 225,97,59 | − | + | [67] | Flavonoids |

| 1.21 | 343.1029 | −1.62 | Hydrocaffeic acid hexoside | C15H20O9 | 181,179,161,119 | + | + | [64] | Phenolic acids |

| 1.21 | 389.1090 | 0.17 | Oleoside/secologanoside | C16H22O12 | 345,209,183,165,121,89,69 | − | + | [61,62] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.22 | 215.0328 | −0.85 | Bergapten | C12H8O4 | 179,161,149,113,89,71 | + | − | [68] | Furanocoumarins |

| 1.23 | 181.0716 | −0.89 | Sugar alcohol | C6H14O6 | 163,149,119,101,89,71,59 | + | − | [63] | Saccharides |

| 1.24 | 179.0560 | −0.63 | Hexose | C6H12O6 | 135,89,71,59 | + | + | [63] | Saccharides |

| 1.26 | 341.1089 | 3.50 | Caffeic acid hexoside | C15H18O9 | 179,161,119,89,59 | + | + | [61] | Phenolic acids |

| 1.26 | 387.1144 | Caffeic acid derivative | --- | 341,179,161,119,89 | + | + | [66] | Phenolic acids | |

| 1.26 | 731.2211 | 2.58 | Oleoside/secologanoside derivative | C35H40O17 | 389,343,227 | − | + | [69] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.28 | 181.0718 | 0.21 | Sugar alcohol isomer | C6H14O6 | 163,149,119,101,89,71,59 | + | − | [63] | Saccharides |

| 1.28 | 375.1294 | −0.72 | Loganic acid | C16H24O10 | 331,317,213,195,165 | − | + | [62] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.28 | 401.1238 | −0.97 | Hexamethoxyflavone | C21H22O8 | 355,341,193,179,161 | + | − | Flavonoids | |

| 1.28 | 407.1552 | −1.68 | Acyclodihydroelenolic acid hexoside | C17H28O11 | 389,377,363,345,233,151 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.28 | 447.1140 | −0.30 | Dihyroxybenzoic acid hexoside pentoside | C18H24O13 | 349,265,195,152 | − | + | [65] | Phenolics |

| 1.28 | 537.1825 | −0.98 | Loganic acid hexoside | C22H34O15 | 537,375 | − | + | [67] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.28 | 731.2236 | 5.92 | Oleoside/secologanoside derivative | C35H40O17 | 389,345,343,227 | − | + | [69] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.30 | 685.2342 | −1.06 | (Iso)Nuzhenide | C31H42O17 | 523,453,421,403,387 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 1.39 | 213.0769 | 0.25 | Decarboxy-hydroxy-elenolic acid | C10H14O5 | 183,169,151,139,107 | − | + | [63] | Phenol ethers |

| 1.76 | 151.0400 | −0.45 | Oxidized hydroxytyrosol | C8H8O3 | 123,109,95,81,77 | − | + | [61] | Phenylalcohols & derivatives |

| 1.99 | 403.1242 | −0.96 | Elenolic acid hexoside/Oleoside methylester | C17H24O11 | 371,333,223,179,119,89 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 2.02 | 197.0820 | 0.35 | Decarboxymethyl elenolic acid dialdehyde | C10H14O4 | 153,137,123 | − | + | [63] | Secoiridoids |

| 2.22 | 435.1295 | −0.39 | Phlorizin | C21H24O10 | 273,255,229,123 | + | − | [64] | Others |

| 2.35 | 315.1086 | 0.19 | Hydroxytyrosol hexoside | C14H20O8 | 153,135,123 | − | + | [62] | Secoiridoids |

| 2.38 | 403.1969 | −1.13 | 2-(2-ethyl-3-hydroxy-6-propionylcyclohexyl) acetic acid glucoside | C19H32O9 | 223 | − | + | [65] | Others |

| 2.39 | 339.0720 | −0.46 | Esculin | C15H16O9 | 177,133 | + | + | [70] | Coumarins |

| 2.41 | 353.0876 | −0.58 | Caffeoylquinic acid | C16H18O9 | 315,191,173,153,124 | − | + | [61] | Phenolic acids |

| 2.57 | 193.0507 | 0.35 | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 149,121,77 | + | − | [60] | Phenolic acid |

| 2.64 | 313.0927 | −0.61 | Vanillin hexoside | C14H18O8 | 151,123 | − | + | [61] | Phenolic aldehyde |

| 3.19 | 153.0558 | 0.00 | Hydroxytyrosol | C8H10O3 | 123,95,77 | − | + | [61] | Phenylalcohols & derivatives |

| 3.29 | 551.1408 | 0.31 | Caffeoyl secologanoside (Cafselogoside) | C25H28O14 | 507,389,341,281,251,161 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 3.94 | 525.1601 | −2.28 | Demethyl-oleuropein | C24H30O13 | 389,363,319,249,209,165 | − | + | [61] | secoiridoids |

| 4.19 | 601.1534 | −4.79 | Elenolic acid glucoside derivative | C29H29O15 | 445, 403,223,179 | − | + | [63] | Secoiridoids |

| 4.20 | 565.1773 | −0.19 | Elenolic acid dihexoside | C23H34O16 | 505,445,403,371,265,223,179, 89 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 4.44 | 625.1409 | −0.19 | Quercetin-O-dihexoside | C27H30O17 | 463,301 | + | − | [71] | Flavonoids |

| 4.46 | 289.0717 | −0.21 | (Epi)catechin | C15H14O6 | 245,203 | + | − | [39] | Flavonoids |

| 4.49 | 489.1605 | −1.77 | Caffeic acid dihexoside | C21H30O13 | 265,163,145 | − | + | [67] | Phenolic acid |

| 4.59 | 403.1230 | −1.48 | Elenolic acid hexoside/Oleoside methylester | C18H26O13 | 371,269,223,179,89 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 4.80 | 755.2042 | 0.24 | Kaempferol coumaroyl diglucoside | C33H40O20 | 593,446,285 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 4.83 | 609.1456 | −0.83 | Kaempferol-di-O-hexoside | C27H30O16 | 489,447,327,285 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 4.96 | 401.1448 | −1.30 | Secologanic acid | C18H26O10 | 269,233,161,101 | − | + | [72] | Irridoid precursor |

| 4.97 | 335.1136 | 0.00 | Hydroxy-oleacin | C17H20O7 | 199,181,155,111,85 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.15 | 389.1446 | −1.85 | Loganin | C17H26O10 | 357,313,253,151,101 | − | + | [62] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.29 | 385.1864 | −1.02 | Icariside B2 | C19H30O8 | 223,205,153 | + | + | [73] | Flavonoids |

| 5.29 | 431.1918 (385 + 46) | 3.84 | Sinapoyl-hexoside | C17H22O10 | 385,223,205,161,153 | + | + | [64] | Hydroxycinnamic acids |

| 5.36 | 609.1456 | −0.83 | Quercetin hexoside deoxyhexoside | C27H30O16 | 447,301 | − | + | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 5.48 | 361.0927 | >10 | Ligstrosideaglycone | C19H22O7 | 317,225,165,137,95 | − | + | [63] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.48 | 535.1471 | 2.59 | Comselogoside | C25H28O13 | 489,389,265,205 | − | + | [65] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.50 | 349.1289 | −1.08 | Decarboxy-hydroxy-elenolic acid linked to hydroxytyrosol | C18H22O7 | 331,300,271,213,181,111 | − | + | [63] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.50 | 687.2131 | −1.58 | Demethyl-oleuropein hexoside | C30H40O18 | 525,389,319,195 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.62 | 651.1563 | −0.57 | Quercetin-acetyl-di-hexoside | C29H32O17 | 531,489, 446,327,285 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 5.64 | 391.1403 | 1.17 | Methyl oleuropein aglycone | C20H24O8 | 345,265,235,229,193,134 | − | + | [62] | Secoiridoids |

| 5.77 | 423.0923 | −2.33 | Maclurin-O-hexoside | C19H20O11 | 287,261,219 | + | − | [64] | Benzophenones |

| 5.89 | 739.2440 | −2.01 | Oleuropein derivative | C34H44O18 | 701,539,377,307 | − | + | Secoiridoids | |

| 5.95 | 415.1602 | −1.86 | Phenylethyl primeveroside | C19H28O10 | 149,251,221,191,89 | − | + | [61] | Simple phenols |

| 5.99 | 739.2091 | 0.00 | Kaempferol-O-deoxyhexose-O-hexose-deoxyhexoside | C33H40O19 | 593,431,285 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 6.00 | 393.1193 | 0.49 | Hydroxy oleuropein aglycone | C19H22O9 | 361,345,317,289,257,181,137 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.00 | 491.0830 | −0.23 | Isorhamnetin-O-glucuronide | C22H20O13 | 315,300 | + | + | [63] | Flavonoids |

| 6.01 | 741.2488 | 3.94 | Oleoside dimethylester diglucoside | C30H46O22 | 579, 417 | − | + | [72] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.10 | 481.1917 | −2.01 | Hydroxytyrosol rhamnoside | C20H34O13 | 417,213,153 | − | + | [70] | Hydroxycinnamic acids |

| 6.14 | 303.0509 | −0.42 | Taxifolin | C15H12O7 | 285,259,177,151,125 | − | + | [67] | Flavonoids |

| 6.16 | 583.2014 | −3.14 | Lucidumoside C | C27H36O14 | 537,461,389,375,313 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.46 | 555.1711 | −1.49 | Hydroxy-oleuropein/Secologanoside | C25H32O14 | 537,403,393,323,291,223,151 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.49 | 593.1497 | −2.52 | Kaempferol hexoside deoxyhexoside | C27H30O15 | 447,285 | + | + | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 6.67 | 557.2248 | 1.50 | Oleoside-O-(hydroxy-dimethyl-octenoyl) | C26H38O13 | 539,511,405,395,343,325,227,185,151 | − | + | [66] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.68 | 449.1071 | −4.09 | Eriodictyol-O-hexoside | C21H22O11 | 287 | + | + | [39] | Flavonoids |

| 6.72 | 375.1429 | −5.40 | Olivil | C20H23O7 | 327,195,179 | − | + | [62] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.75 | 421.1702 | −3.17 | Dihydro Oleoside dimethylester | C18H30O11 | 359,239,165,119 | − | + | [66] | Secoiridoids |

| 6.84 | 635.1613 | −0.72 | Kaempferol-O-(acetyl-hexoside)-O-deoxyhexoside | C29H32O16 | 489,431,285 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 6.89 | 447.0927 | −1.31 | Luteolin-O-hexoside | C21H20O11 | 285,255,227,151 | + | + | [61] | Flavonoids |

| 6.92 | 287.0557 | −1.43 | Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 | 259,243,177,151,125 | − | + | [74] | Flavonoids |

| 7.03 | 311.0402 | −2.11 | Caftaric acid | C13H12O9 | 243,179,161,135 | − | + | [39] | Phenolic acid |

| 7.06 | 327.2174 | −0.91 | Trihydroxy octadecadienoic acid | C18H32O5 | 283,229,211,171 | + | + | [63] | Fatty acids |

| 7.08 | 623.1972 | −1.51 | Verbascoside | C29H36O15 | 461,161 | + | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.10 | 543.2076 | −1.31 | Dihydro oleuropein | C25H36O13 | 525,513,407,389,377,357,313,197,151,119 | − | + | [70] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.17 | 701.2292 | −0.91 | Oleuropein hexoside | C31H42O18 | 539,437,377,307,275,223,179,149,89 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.17 | 723.2123 | −2.61 | Ligustroflavone | C33H40O18 | 561,543,491,459,437,329,297 | − | + | [71] | Flavonoids |

| 7.25 | 463.0876 | −1.26 | Myrecetin-O-deoxyhexoside | C21H20O12 | 316,301,287,271,257 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 7.25 | 535.1813 | −1.49 | Hydroxypinoresinol -O-hexoside | C26H32O12 | 355,295,179 | − | + | [67] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.28 | 419.1344 | −0.85 | Deoxyphlorizin | C21H24O9 | 257,239 | + | − | [64] | Others |

| 7.33 | 477.1399 | −0.70 | Calceolarioside A | C23H26O11 | 323,314,161 | − | + | [65] | Pentacyclic triterpenes |

| 7.40 | 447.0918 | −3.32 | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer | C21H20O11 | 285,347 | − | + | [61] | Flavonoids |

| 7.40 | 607.1639 | −4.85 | Diosmin | C28H32O15 | 461,299,145 | − | + | [67] | Flavonoids |

| 7.49 | 431.0978 | 0.95 | Apigenin-O-hexoside | C21H20O10 | 269,268 | + | + | [61] | Flavonoids |

| 7.52 | 539.2127 | threo-7,9,9′-Trihydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxy-8-O-4′-neolignan-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | C26H36O12 | 493,361 | + | − | [73] | Lignans | |

| 7.53 | 593.1501 | −1.84 | Luteolin-O-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | 447,285 | − | + | [63] | Flavonoids |

| 7.56 | 433.1131 | −2.12 | Naringenin hexoside | C21H22O10 | 271 | + | − | [75] | Flavonoids |

| 7.57 | 505.0945 | −8.44 | Trihydroxy dimethoxyflavone glucuronide | C23H22O13 | 341,329,300,271 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 7.61 | 325.0928 | −0.28 | Coumaroylhexose | C15H18O8 | 163 | + | − | [66] | Phenolics |

| 7.61 | 329.1392 | Trihydroxy dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O7 | 314,299,269,229,211 | + | − | [60] | Flavonoids | |

| 7.62 | 671.2190 | −0.41 | Oleuropein pentoside | C30H40O17 | 539,377,307,275,149 | − | + | [71] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.64 | 195.0660 | −1.03 | Hydroxytyrosol acetate | C10H12O4 | 177,159,151,135,107 | − | + | [70] | Phenylalcohols & derivatives |

| 7.68 | 329.2329 | −1.36 | Trihydroxy octadecenoic acid | C18H34O5 | 314,299,269,229,211,193,171,139 | + | + | [63] | Fatty acids |

| 7.69 | 463.0881 | −0.21 | Quercetin-O-hexoside | C21H20O12 | 301 | − | + | [67] | Flavonoids |

| 7.71 | 461.1084 | −1.16 | Diosmetin-O-hexoside | C22H22O11 | 299,285,255,145 | − | + | [67] | Flavonoids |

| 7.72 | 287.2226 | −0.63 | Dihydroxypalmitic acid | C16H32O4 | 269 | + | + | [66] | Fatty acids |

| 7.81 | 593.1534 | 3.72 | Vicenin 2 | C27H30O15 | 547,473,383,353,325,297 | − | + | [69] | Flavonoids |

| 7.83 | 489.1034 | −0.92 | Kaempferol-O-acetyl-hexoside | C23H22O12 | 327,284,285,255,227 | + | − | [39] | Flavonoids |

| 7.88 | 377.1238 | −1.04 | Eriodictyol derivative | C19H22O8 | 287,269,257,229,163 | + | − | [39] | Flavonoid |

| 7.89 | 541.1911 | −2.89 | Hydro oleuropein | C25H34O13 | 361,329,225,193,181,149,121,89 | − | + | [70] | Secoiridoids |

| 7.93 | 577.1608 | 7.83 | Apigenin-O-hexosyl rhamnoside | C27H30O14 | 415,269 | − | + | [70] | Flavonoids |

| 8.15 | 579.1692 | −4.71 | Naringin | C27H32O14 | 543,525,513,389,377,271 | − | + | [39] | Flavonoids |

| 8.17 | 539.1762 | −0.77 | Oleuropein | C25H32O13 | 539,377,307,275,223,179,149,89 | − | + | [76] | Secoiridoids |

| 8.24 | 597.1349 | Oleuropein derivative | 539,507,377,307,275,223,149 | − | + | [69] | Secoiridoids | ||

| 8.43 | 753.2250 | 0.33 | Trihydroxy-methoxyflavone-O-deoxyhexose-deoxhexose-hexoside | C34H42O19 | 299 | + | − | [64] | Flavonoids |

| 8.51 | 307.1915 | Catechin hydrate | C15H16O7 | 289,235,211,185,169,121,97 | + | − | [39] | Flavonoids | |

| 8.85 | 537.1601 | −2.35 | Fraxamoside | C25H30O13 | 403,223,151 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 9.00 | 523.1812 | −1.72 | Ligstroside | C25H32O12 | 361,291,259 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 9.03 | 293.1756 | −0.79 | Gingerol | C17H26O4 | 236,221,205,177 | − | + | [65] | Phenolic |

| 9.12 | 925.2980 | −0.33 | Jaspolyoside | C42H54O23 | 749,701,539,377,307,149 | − | + | [71] | Flavonoids |

| 9.21 | 847.2677 | 1.28 | Oleuropein derivative | C40H48O20 | 685, 583,539, 377,307 | − | + | [69] | Secoiridoids |

| 9.36 | 877.2771 | −0.09 | Oleuropein derivative | C41H50O21 | 715,539 | − | + | [69] | Secoiridoids |

| 9.94 | 377.1237 | −1.30 | Oleuropeine aglycone | C19H22O8 | 241,327,307,199,153 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 10.81 | 357.1338 | −1.57 | Pinoresinol | C20H22O6 | 295, 221,189,122,83 | + | − | [65] | Lignan |

| 11.29 | 375.1079 | −1.70 | Dehyro-Oleuropein aglycone | C19H20O8 | 375,343,207,195,189, 177,163,135 | − | + | [61] | Secoiridoids |

| 11.34 | 285.0402 | −0.70 | Kampferol (tetrahydroxyflavone) | C15H10O6 | 257,239,229,185,151,131 | + | − | [74] | Flavonoids |

| 12.19 | 373.1287 | −1.55 | Hydroxy pinoresinol/Africanal | C20H22O7 | 311,289,237,163,119 | − | + | [66] | Lignan |

| 12.29 | 315.0480 | −9.60 | (Iso)rhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 300,163,145 | − | + | [61] | Flavonoids |

| 12.32 | 293.2120 | −0.74 | Hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid | C18H30O3 | 275,235,223,183,171 | + | − | [39] | Fatty acids |

| 12.68 | 271.2277 | −0.62 | Hydroxyhexadecanoic acid | C16H32O3 | --- | + | − | [39] | Fatty acids |

| 12.76 | 313.0712 | −1.80 | Cirsimaritin | C17H14O6 | 298,283,253,225, 197,163,143,119 | + | − | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Cirsimaritin#section = MS-MS (accessed on 1 September 2025) | Flavonoids |

| 13.47 | 345.1705 | −0.72 | Epi(rosmanol) | C20H26O5 | 301,283,257,177,133 | + | − | [60] | Phenolic terpenes |

| 13.61 | 295.2274 | −1.59 | Hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid | C18H32O3 | 277,195,171 | + | − | [39] | Fatty acids |

| 17.87 | 471.3471 | −1.88 | Maslinic acid | C30H47O4 | 423,405,393,249 | − | + | [61] | Pentacyclic triterpenes |

| 18.10 | 299.0586 | 8.32 | Kaempferide | C16H12O6 | 284,227 | + | − | [39] | Flavonoids |

| 19.33 | 277.2170 | −1.08 | Linolenic acid (C18:3) | C18H30O2 | --- | + | − | [66] | Fatty acids |

| 20.75 | 301.2171 | −0.68 | Methenolone | C20H30O2 | 220,205 | + | − | [77] | Steroids |

| 22.16 | 455.3522 | −1.91 | Betulinic acid | C30H48O3 | --- | − | + | [61] | Pentacyclic triterpenes |

| 23.09 | 255.2329 | 0.00 | Palmitic acid (C16:1) | C16H32O2 | --- | + | + | [39] | Fatty acids |

| 23.81 | 281.2485 | −0.37 | Oleic acid (C18:1) | C18H34O2 | --- | + | + | [66] | Fatty acids |

| Groups | Viability% | Abnormalities% | Concentrations (×106/mL) | Motility% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI (control) | 75 ± 2.1 b | 10 ± 0.8 b | 29 ± 0.8 b | 76 ± 0.8 b |

| GII (MTZ) | 37 ± 1.1 a | 40 ± 2.1 a | 9.1 ± 1.1 a | 29 ± 1.8 a |

| GIII (EA) | 75 ± 0.8 b | 9 ± 0.5 b | 27.4 ± 1.2 b | 74 ± 0.9 b |

| GIV (OE) | 75 ± 0.5 b | 12.6 ± 1.7 b | 28.6 ± 0.8 b | 75 ± 2.8 b |

| GV (MTZ + EA) | 57 ± 2.1 ab | 22.6 ± 1.1 ab | 28.2 ± 1.1 b | 75± 1.5 b |

| GVI (MTZ + OE) | 42 ± 1.4 ab | 28 ± 1.5 ab | 21.6 ± 1.2 ab | 50 ± 1.8 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Azouz, A.A.; Ali, A.M.; Shaalan, M.; Rashad, M.M.; Bakeer, M.R.; Issa, M.Y.; Kadasah, S.F.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Azouz, R.A. Protective Effects of Olea europaea L. Leaves and Equisetum arvense L. Extracts Against Testicular Toxicity Induced by Metronidazole Through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Regulating NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Signaling Pathways. Toxics 2026, 14, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010042

Azouz AA, Ali AM, Shaalan M, Rashad MM, Bakeer MR, Issa MY, Kadasah SF, Alrefaei AF, Azouz RA. Protective Effects of Olea europaea L. Leaves and Equisetum arvense L. Extracts Against Testicular Toxicity Induced by Metronidazole Through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Regulating NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Signaling Pathways. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzouz, Asmaa A., Alaa M. Ali, Mohamed Shaalan, Maha M. Rashad, Manal R. Bakeer, Marwa Y. Issa, Sultan F. Kadasah, Abdulmajeed Fahad Alrefaei, and Rehab A. Azouz. 2026. "Protective Effects of Olea europaea L. Leaves and Equisetum arvense L. Extracts Against Testicular Toxicity Induced by Metronidazole Through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Regulating NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Signaling Pathways" Toxics 14, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010042

APA StyleAzouz, A. A., Ali, A. M., Shaalan, M., Rashad, M. M., Bakeer, M. R., Issa, M. Y., Kadasah, S. F., Alrefaei, A. F., & Azouz, R. A. (2026). Protective Effects of Olea europaea L. Leaves and Equisetum arvense L. Extracts Against Testicular Toxicity Induced by Metronidazole Through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Regulating NBN, INSL-3, STAR, HSD-3β, and CYP11A1 Signaling Pathways. Toxics, 14(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010042