Assessment of Effects of Discharged Firefighting Water on the Nemunas River Based on Biomarker Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Collection of Mussels

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. PAHs Analysis in Mussels

2.3.2. Metal Analysis in Mussels

2.3.3. Preparation for Biochemical Biomarkers Analysis, Evaluation of PAH Metabolites

2.3.4. Assessment of Antioxidant Capacity

2.3.5. Measurement of AChE Activity

2.3.6. Determination of Environmental Geno- and Cytotoxicity in U. pictorum Gill Cells

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Analysis in U. pictorum

3.2. Biomarker Responses

3.2.1. Antioxidant Capacity and PAHs Metabolites

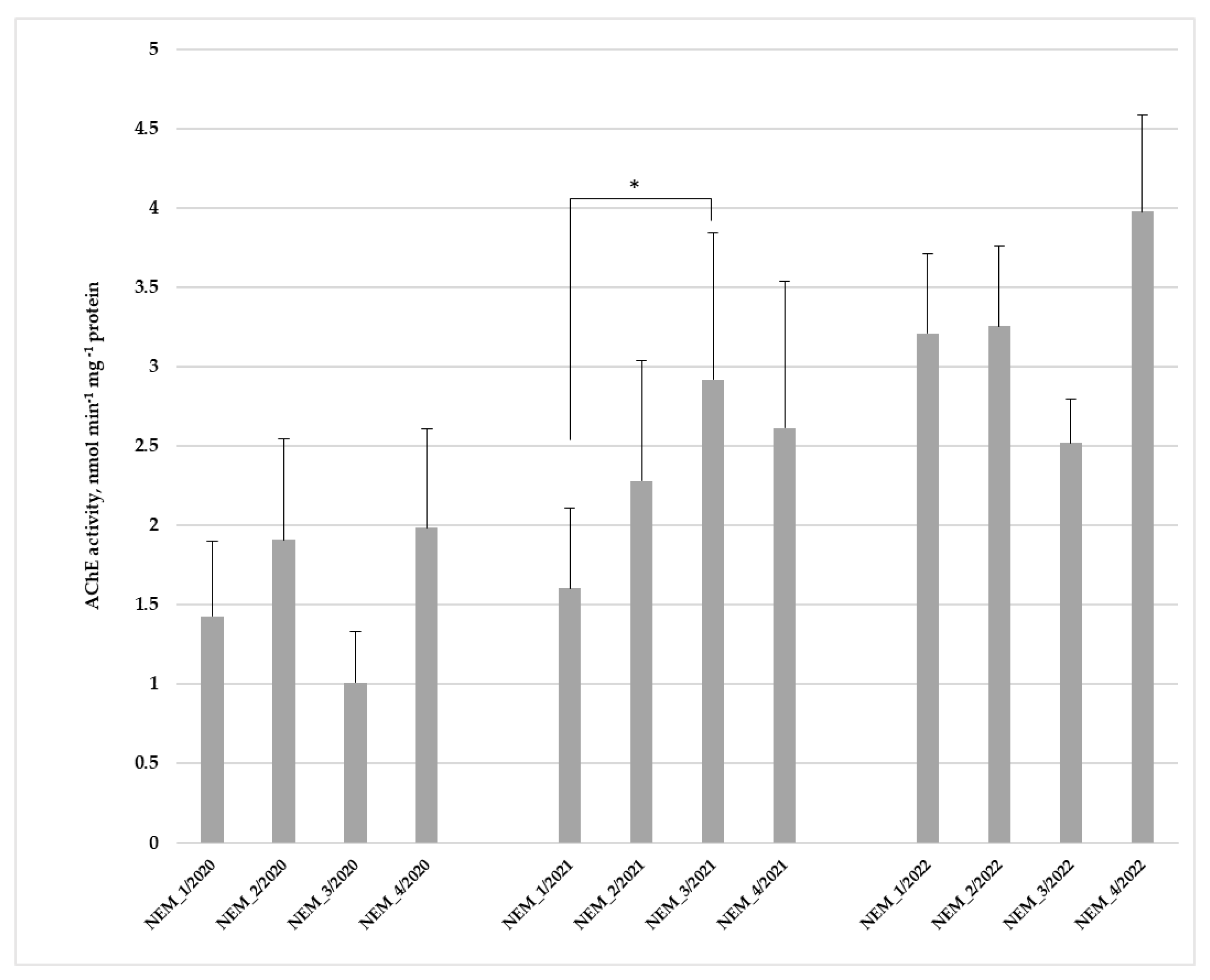

3.2.2. Acetylcholinesterase Activity

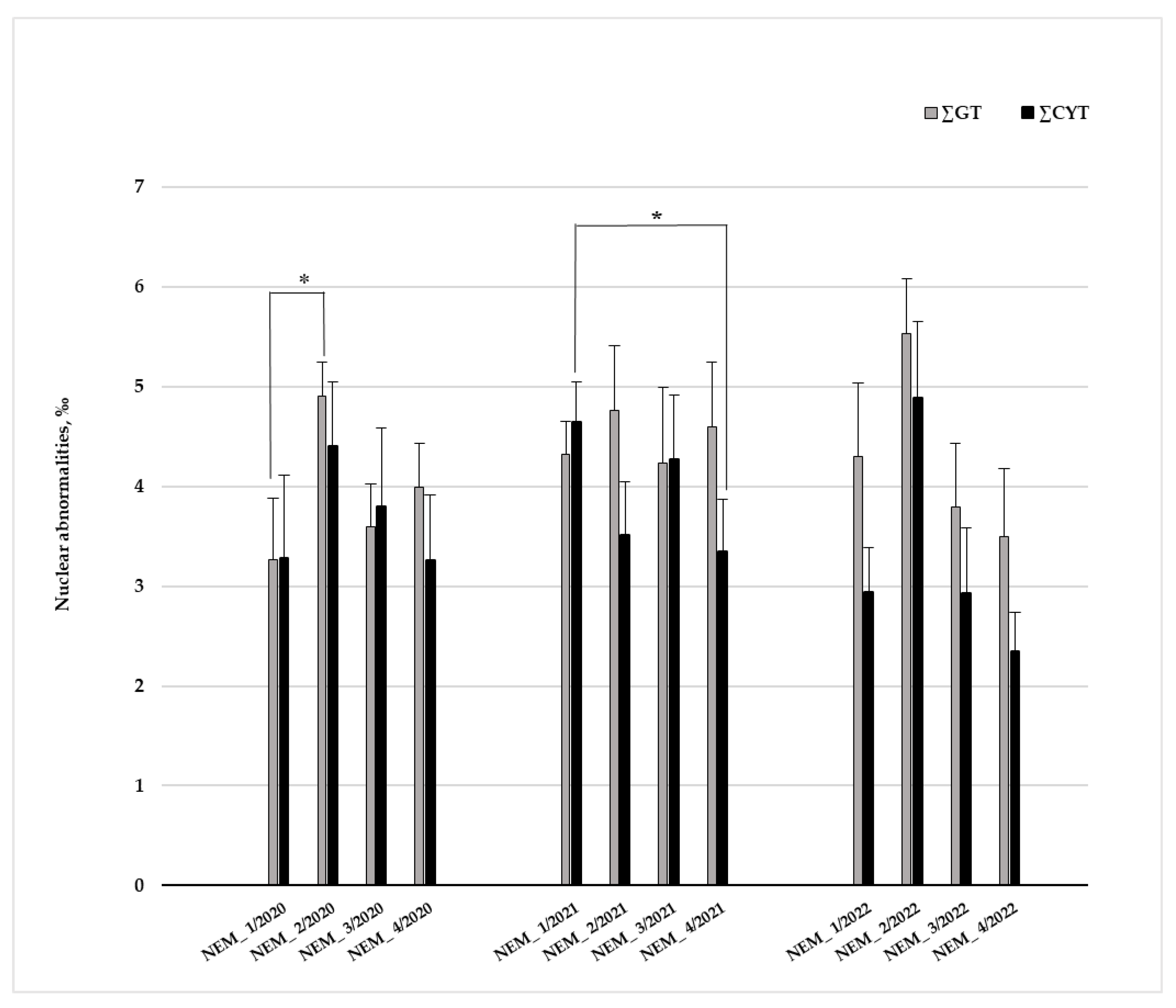

3.2.3. Environmental Geno- and Cytotoxicity

3.3. PCA Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raudonytė-Svirbutavičienė, E.; Stakėnienė, R.; Jokšas, K.; Valiulis, D.; Byčenkienė, S.; Žarkov, A. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals in soil following a large tire fire incident: A case study. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gefenienė, A.; Zubrytė, E.; Kaušpėdienė, R.; Ramanauskas, R.; Ragauskas, R. Firefighting wastewater from a tire recycling plant: Chemical characterization and simultaneous removal of multiple pollutants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.N. Genotoxicological studies in aquatic organisms: An overview. Mutat. Res. 2004, 552, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, M.J.; Svendsen, C.; Bedaux, J.J.M.; Bongers, M.; Kammenga, J.E. Significance testing of synergistic/antagonistic, dose level-dependent, or dose ratio-dependent effects in mixture dose–response analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005, 24, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondero, F.; Banni, M.; Negri, A.; Boatti, L.; Dagnino, A.; Viarengo, A. Interactions of a pesticide/heavy metal mixture in marine bivalves: A transcriptomic assessment. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, W.; Escher, B.I.; Muller, E.; Schmitt-Jansen, M.; Schulz, T.; Slobodnik, J.; Hollert, H. Towards a holistic and solution-oriented monitoring of chemical status of European water bodies: How to support the EU strategy for a non-toxic environment? Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carere, M.; Antoccia, A.; Buschini, A.; Frenzilli, G.; Marcon, F.; Andreoli, C.; Gorbi, G.; Suppa, A.; Montalbano, S.; Prota, V.; et al. An integrated approach for chemical water quality assessment of an urban river stretch through Effect-Based Methods and emerging pollutants analysis with a focus on genotoxicity. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 300, 113549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Amaral, Q.D.F.; Da Rosa, E.; Wronski, J.G.; Zuravski, L.; Querol, M.V.M.; Dos Anjos, B.; de Andrade, C.F.F.; Machado, M.M.; de Oliveira, L.F.S. Golden mussel (Limnoperna fortunei) as a bioindicator in aquatic environments contaminated with mercury: Cytotoxic and genotoxic aspects. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 675, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labieniec, M.; Biernat, M.; Gabryelak, T. Response of digestive gland cells of freshwater mussel Unio tumidus to phenolic compound exposure in vivo. Cell. Biol. Int. 2007, 31, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štambuk, A.; Pavlica, M.; Vignjević, G.; Bolarić, B.; Klobučar, G.I.V. Assessment of genotoxicity in polluted freshwaters using caged painter’s mussel, Unio pictorum. Ecotoxicology 2009, 18, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, P.; Frenzilli, G.; Benedetti, M.; Bernardeschi, M.; Falleni, A.; Fattorini, D.; Regoli, F.; Scarcelli, V.; Nigro, M. Antioxidant, genotoxic and lysosomal biomarkers in the freshwater bivalve (Unio pictorum) transplanted in a metal polluted river basin. Aquat. Toxicol. 2010, 100, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, P.; Bernardeschi, M.; Scarcelli, V.; Cantafora, E.; Benedetti, M.; Falleni, A.; Frenzilli, G. Lysosomal, genetic and chromosomal damage in haemocytes of the freshwater bivalve (Unio pictorum) exposed to polluted sediments from the River Cecina (Italy). Chem. Ecol. 2017, 33, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfushynska, H.I.; Gnatyshyna, L.L.; Stoliar, O.B. Effect of in situ exposure history on the molecular responses of freshwater bivalve Anodonta anatina (Unionidae) to trace metals. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 89, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuković-Gačić, B.; Kolarević, S.; Sunjog, K.; Tomović, J.; Knežević-Vukčević, J.; Paunović, M.; Gačić, Z. Comparative study of the genotoxic response of freshwater mussels Unio tumidus and Unio pictorum to environmental stress. Hydrobiologia 2014, 735, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Lima, M.; Hattori, A.; Kondo, T.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.K.; Shirai, A.; Hayashi, H.; Usui, T.; Sakuma, K.; Toriya, T.; et al. Freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) from the Rising Sun (Far East Asia): Phylogeny, systematics, and distribution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 146, 106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Martinez, L.; Romero, D.; Rubio, C.P.; Tecles, F.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Teles, M.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. New potential biomarkers of oxidative stress in Mytilus galloprovincialis: Analytical validation and overlap performance. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 221, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.M.; Andersen, O.K.; Galloway, T.S.; Depledge, M.H. Rapid assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposure in decapod crustaceans by fluorimetric analysis of urine and haemolymph. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 67, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayake, A.; Bamber, S.D. Monitoring PAH contamination in the field (South west Iberian Peninsula): Biomonitoring using fluorescence spectrophotometry and physiological assessments in the shore crab Carcinus maenas (L.) (Crustacea: Decapoda). Mar. Environ. Res. 2010, 70, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruczyńska, W.M.; Szlinder-Richert, J.; Malesa-Ciećwierz, M.; Warzocha, J. Assessment of PAH pollution in the southern Baltic Sea through the analysis of sediment, mussels and fish bile. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalivaikienė, R.; Kalcienė, V.; Butrimavičienė, L. Response of oxidative stress and neurotoxicity biomarkers in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) after exposure to six-metal mixtures. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Phy. 2024, 57, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P.E. Acetylcholine modulation of neural systems involved in learning and memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2003, 80, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P.E. Acetylcholine: Cognitive and brain functions. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2003, 80, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrimavičienė, L.; Baršienė, J.; Pažusienė, J.; Stankevičiūtė, M.; Valskienė, R. Environmental genotoxicity and risk assessment in the Gulf of Riga (Baltic Sea) using fish, bivalves, and crustaceans. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24818–24828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butrimavičienė, L.; Stankevičiūtė, M.; Kalcienė, V.; Jokšas, K.; Baršienė, J. Genotoxic, cytotoxic, and neurotoxic responses in Anodonta cygnea after complex metal mixture treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7627–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybakovas, A.; Arbačiauskas, K.; Markovskienė, V.; Jokšas, K. Contamination and genotoxicity biomarker responses in bivalve mussels from the major Lithuanian rivers. EMM 2020, 61, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, K.R.; Loeb, L.A. Significance of multiple mutations in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, D. The morphology, growth and reproduction of Unionidae (Bivalvia) in a Fenland Waterway. J. Molluscan Stud. 1999, 65, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalachova, K.; Pulkrabova, J.; Drabova, L.; Cajka, T.; Kocourek, V.; Hajslova, J. Simplified and rapid determination of polychlorinated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in fish and shrimps integrated into a single method. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 707, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen, M.D. Polycyclic aromatic compounds: Extraction and determination in food. Food Addit. Contam. 1994, 11, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćias-Zamora, J.V.; Mendoza-Vega, E.; Villaescusa-Celaya, J.A. PAHs composition of surface marine sediments: A comparison to potential local sources in Todos Santos Bay, B.C., Mexico. Chemosphere 2002, 46, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, I.; Shandil, A.; Shrivastava, V.S. Study for Determination of Heavy Metals in Fish Species of the River Yamuna (Delhi) by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES). AASR 2011, 2, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “Antioxidant power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V.J.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquené, G.; Galgani, F. Biological effects of contaminants: Cholinesterase inhibition by organophosphate and carbamate compounds. In ICES Techniques in Marine Environmental Science (TIMES); ICES: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.M.; Vethaak, A.D. Integrated Marine Environmental Monitoring of Chemicals and Their Effects. In ICES Cooperative Research Report; No. 315. 277; ICES: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; ISBN 978-87-7482-120-5. [Google Scholar]

- HELCOM. Development of a set of core indicators: Interim report of the HELCOM CORESET project. Part B: Descriptions of the indicators. In Balt. Sea Environment Proceedings; No. 129 B; HELCOM: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7.999. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/kassambara/factoextra (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Binelli, A.; Riva, C.; Cogni, C.; Provini, A. Assessment of the genotoxic potential of benzo(a)pyrene and pp′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene in Zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha). Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2008, 649, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAA Oro kokybės Alytaus Rajone Tyrimai. Available online: https://weather.com/lt-LT/forecast/air-quality/l/1dedeb960925d4986f09d3a32c32beec1aa0615e903b8279c2e9d7fd177929c3 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Česonienė, L.; Šileikienė, D.; Dapkienė, M. The effect of a fire at a tire recycling factory on the status of surface water bodies: A case study in Lithuania. In Rural Development 2023: Bioeconomy for the Green Deal, Proceedings of the 11th International Scientific Conference, Kaunas, Lithuania, 21–22 September 2023; VDU: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.; González-Santamaría, D.E.; García-Delgado, C.; Ruiz, A.; Garralón, A.; Ruiz, A.I.; Fernández, R.; Eymar, E.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R. Impact of a tire fire accident on soil pollution and the use of clay minerals as natural geo-indicators. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 2147–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, M.; Rovira, J.; Díaz-Ferrero, J.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L. Human exposure to environmental pollutants after a tire landfill fire in Spain: Health risks. Environ. Internat. 2016, 97, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovira, J.; Domínguez-Morueco, N.; Nadal, M.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L. Temporal trend in the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons emitted in a big tire landfill fire in Spain: Risk assessment for human health. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2017, 53, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Sukumaran, V.; Yeo, I.; Shim, K.; Lee, S.; Choi, H.; Ha, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Jung, J.; Lee, J.; et al. Phenotypic toxicity, oxidative response, and transcriptomic deregulation of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis exposed to a toxic cocktail of tire-wear particle leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Anthropogenic impacts on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface water: Evidence from the COVID-19 lockdown. Water Res. 2024, 262, 122143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.S.; Panthari, D.; Semwal, S.; Uniyal, T. Aftermath of industrial pollution, post COVID-19 quarantine on environment. In The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Green Societies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, J.U.; Siddique, A.B.; Islam, S.; Ali, M.M.; Tokatli, C.; Islam, A.; Pal, S.C.; Idris, A.M.; Malafaia, G.; Islam, A.R.M.T. Effects of COVID-19 era on a subtropical river basin in Bangladesh: Heavy metal(loid)s distribution, sources and probable human health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Bera, B.; Adhikary, P.P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Roy, S.; Saha, S.; Sengupta, D.; Shit, P.K. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown and unlock on the health of tropical large river with associated human health risk. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 37041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, H.; Thompson, J.R.; Li, J.; Loiselle, S.; Duan, H. COVID-19 lockdown improved river water quality in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Liu, R.; Wu, H.; Shen, M.; Yousaf, B.; Wang, X. COVID-19 lockdown measures affect polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons distribution and sources in sediments of Chaohu Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, P.T.; Norwood, W.P.; Prepas, E.E.; Pyle, G.G. Metal-PAH mixtures in the aquatic environment: A review of co-toxic mechanisms leading to more-than-additive outcomes. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 154, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, G.; Shweta, S.; Patel, P. Oxidative stress and free radicals in disease pathogenesis: A review. Discov. Med. 2025, 2, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Patnaik, L. Acetylcholinesterase, as a potential biomarker of naphthalene toxicity in different tissues of freshwater teleost, Anabas testudineus. J. Environ. Bioremediat. Toxicol. 2021, 29, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainy, A.; Medeiros, M.; Di Mascio, P.; Almeida, E. In vivo effects of metals on the acetylcholinesterase activity of the Perna perna mussel’s digestive gland. Biotemas 2006, 19, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kopecka-Pilarczyk, J. The effect of pesticides and metals on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in various tissues of blue mussel (Mytilus trossulus L.) in short-term in vivo exposures at different temperatures. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2010, 45, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Grist, S.; Nugegoda, D. The PAH body burdens and biomarkers of wild mussels in Port Phillip Bay, Australia and their food safety implications. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Dondero, F.; Moore, M.; Negri, A.; Dagnino, A.; Readman, J.; Lowe, D.; Frickers, P.; Beesley, A.; Thain, J.; et al. Integration of biochemical, histochemical and toxicogenomic indices for the assessment of health status of mussels from the Tamar Estuary, U.K. Mar. Environ. Res. 2011, 72, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaloyianni, M.; Dailianis, S.; Chrisikopoulou, E.; Zannou, A.; Koutsogiannaki, S.; Alamdari, D.; Koliakos, G.; Dimitriadis, V. Oxidative effects of inorganic and organic contaminants on haemolymph of mussels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 2009, 149, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobal, V.; Suárez, P.; Ruiz, Y.; García-Martín, O.; San Juan, F. Activity of antioxidant enzymes in Mytilus galloprovincialis exposed to tar: Integrated response of different organs as pollution biomarker in aquaculture areas. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valskys, V.; Valskienė, R.; Ignatavičius, G. Analysis and assessment of heavy metals concentrations in Nemunas river bottom sediments at Alytus city territory. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2015, 23, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station Code | Brief Description of the Station | Geographical Coordinates | Sampling Dates/Number of Mussels (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEM_1 On the figures denoted accordingly NEM_1/2020, 2021, 2022 | The station is located upstream of the Alytus WTP “Dzūkijos vandenys” | 54°25′48.9″ N 24°03′13.8″ E | 2020.06.27, (25) 2021.06.28, (25) 2022.06.28, (25) |

| NEM_2 On the figures denoted accordingly NEM_2/2020, 2021, 2022 | The station is situated about 2.5 km downstream from the outlet of the Alytus City WTP and NEM_1 station | 54°26′58.3″ N 24°03′56.1″ E | 2020.06.27, (25) 2021.06.28, (25) 2022.06.28, (25) |

| NEM_3 On the figures denoted accordingly NEM_3/2020, 2021, 2022 | The station is located on the territory of Nemunas Loop regional park, about 38 km downstream from the outlet and the NEM_1 station | 54°34′01.9″ N 23°58′01.2″ E | 2020.06.28, (25) 2021.06.29, (25) 2022.06.29, (25) |

| NEM_4 On the figures denoted accordingly NEM_4/2020, 2021, 2022 | The station is located about 66–68 km downstream from the Alytus City WTP outlet and the NEM_1 station | 54°39′05.8″ N 24°04′53.2″ E | 2020.06.27, (25) 2021.06.28, (25) 2022.06.28, (25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Butrimavičienė, L.; Kalcienė, V.; Nalivaikienė, R.; Arbačiauskas, K.; Jokšas, K.; Rybakovas, A. Assessment of Effects of Discharged Firefighting Water on the Nemunas River Based on Biomarker Responses. Toxics 2026, 14, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010041

Butrimavičienė L, Kalcienė V, Nalivaikienė R, Arbačiauskas K, Jokšas K, Rybakovas A. Assessment of Effects of Discharged Firefighting Water on the Nemunas River Based on Biomarker Responses. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleButrimavičienė, Laura, Virginija Kalcienė, Reda Nalivaikienė, Kęstutis Arbačiauskas, Kęstutis Jokšas, and Aleksandras Rybakovas. 2026. "Assessment of Effects of Discharged Firefighting Water on the Nemunas River Based on Biomarker Responses" Toxics 14, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010041

APA StyleButrimavičienė, L., Kalcienė, V., Nalivaikienė, R., Arbačiauskas, K., Jokšas, K., & Rybakovas, A. (2026). Assessment of Effects of Discharged Firefighting Water on the Nemunas River Based on Biomarker Responses. Toxics, 14(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010041