Potentially Toxic Elements Accumulation and Health Risk Evaluation in Different Parts of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Sample Processing and Analysis

2.3. Analysis of PTEs Pollution Sources in Different Types of TCMMs

2.4. Assessment of PTEs Contamination Levels in Different Types of TCMMs

2.4.1. The Single-Factor Pollution Index

2.4.2. The Nemerow Pollution Index

2.5. Health Risk Assessment

2.5.1. Non-Carcinogenic Risks

2.5.2. Carcinogenic Risk

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

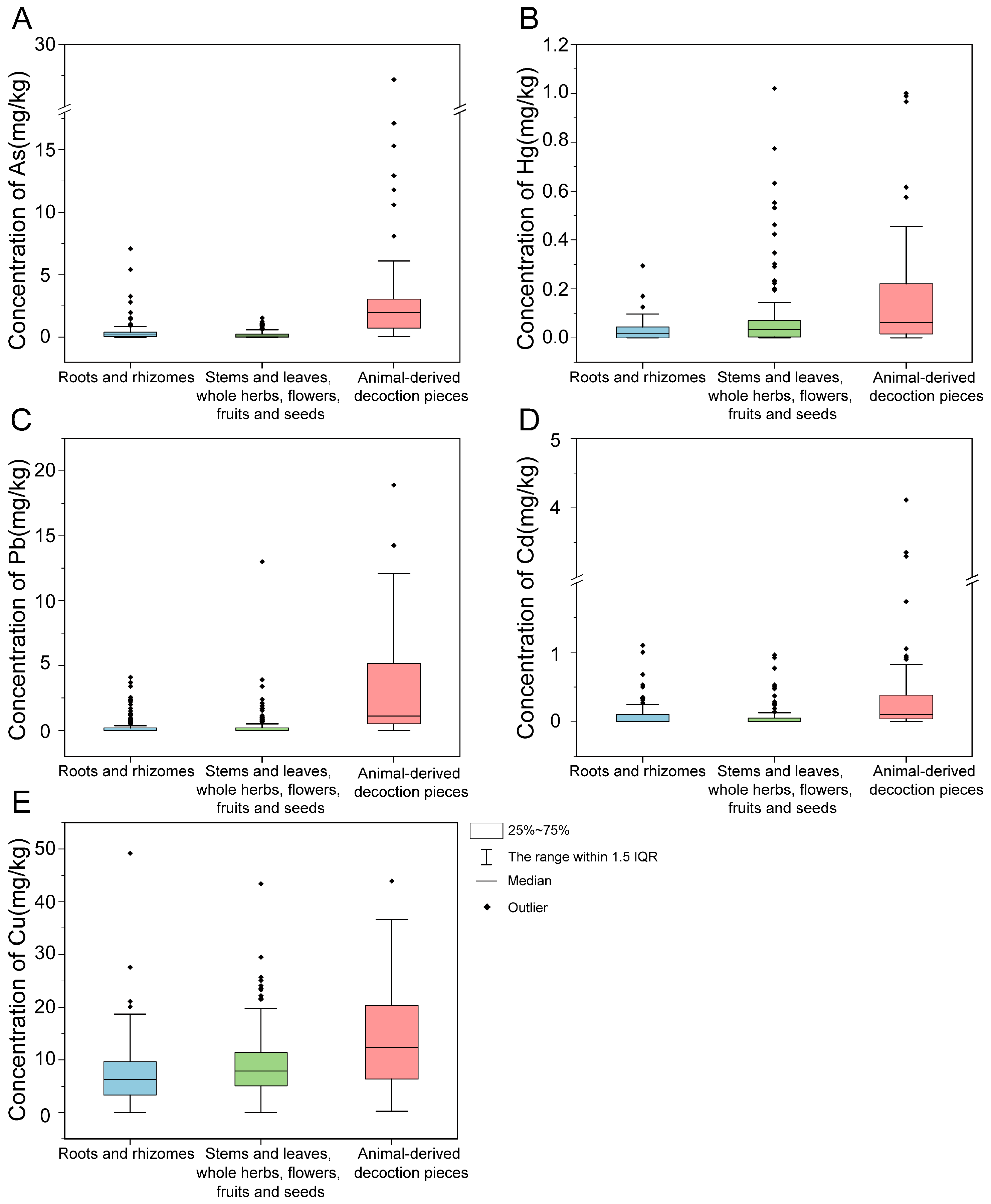

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of HM Concentrations in TCMMs

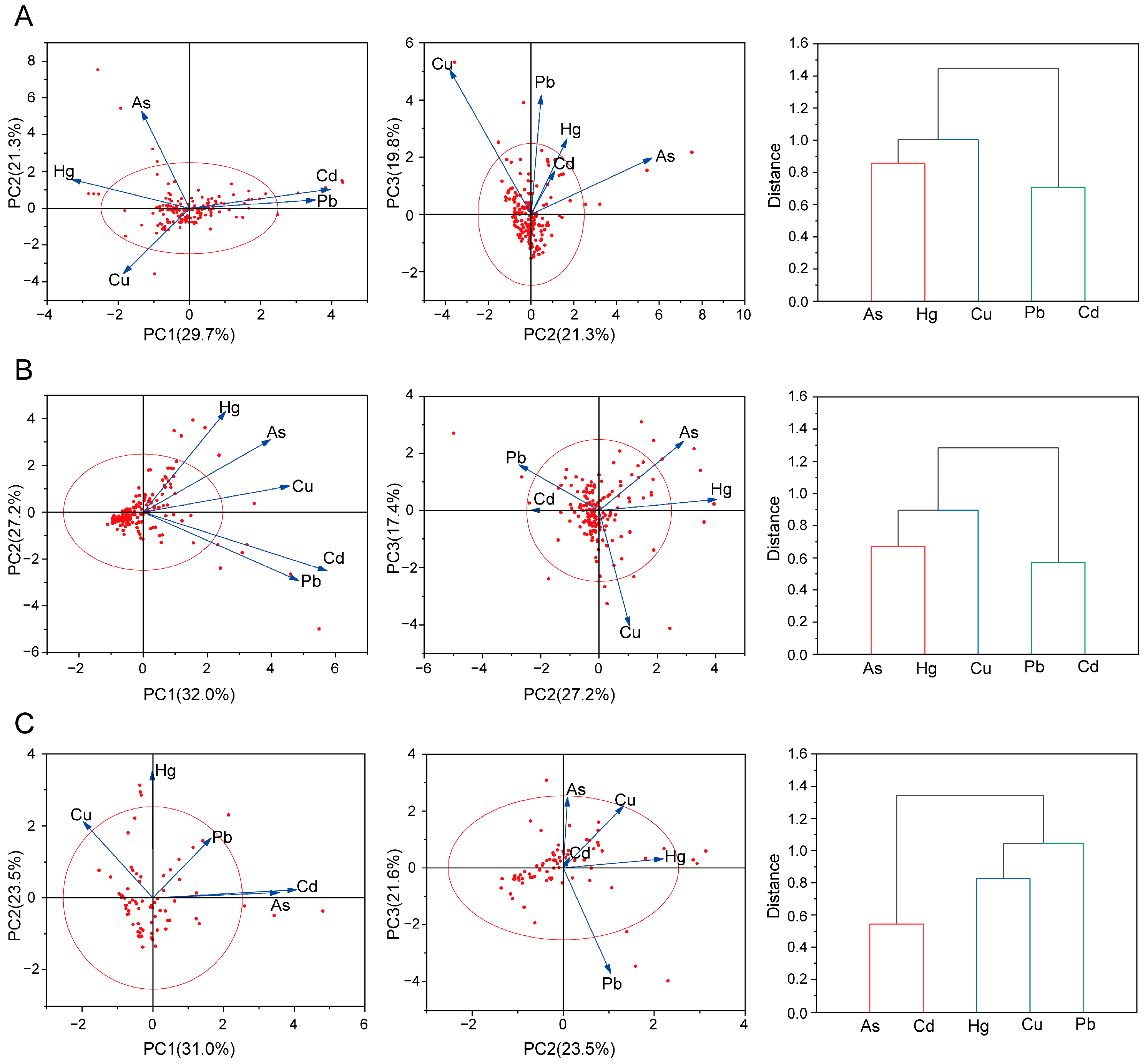

3.2. PCA and Cluster Analysis

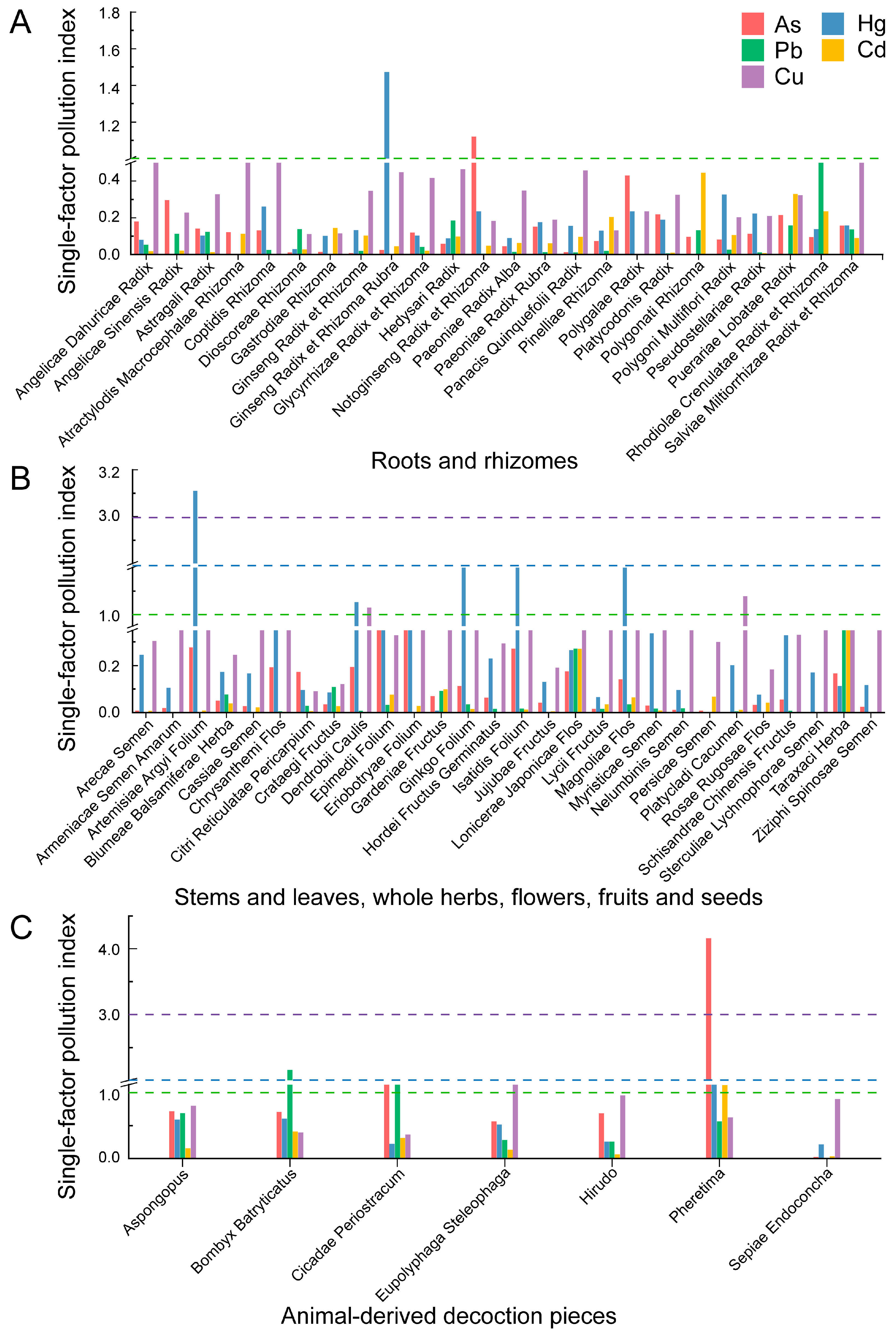

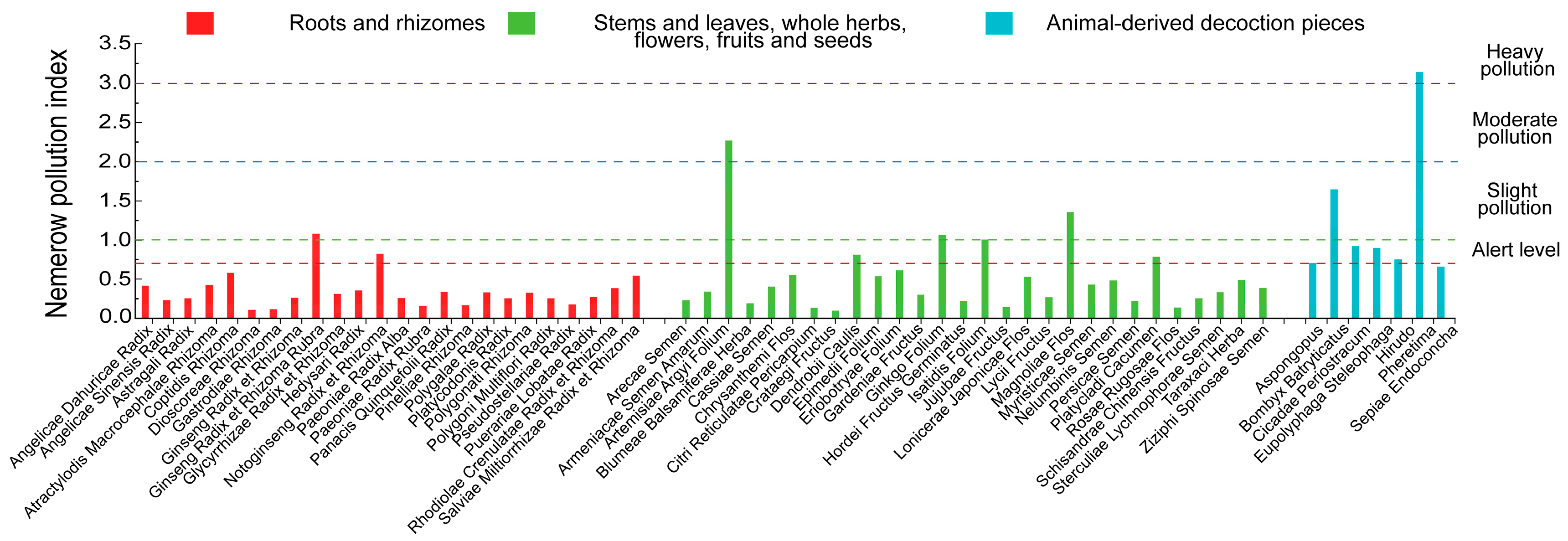

3.3. Results of Evaluation of PTEs Pollution Index

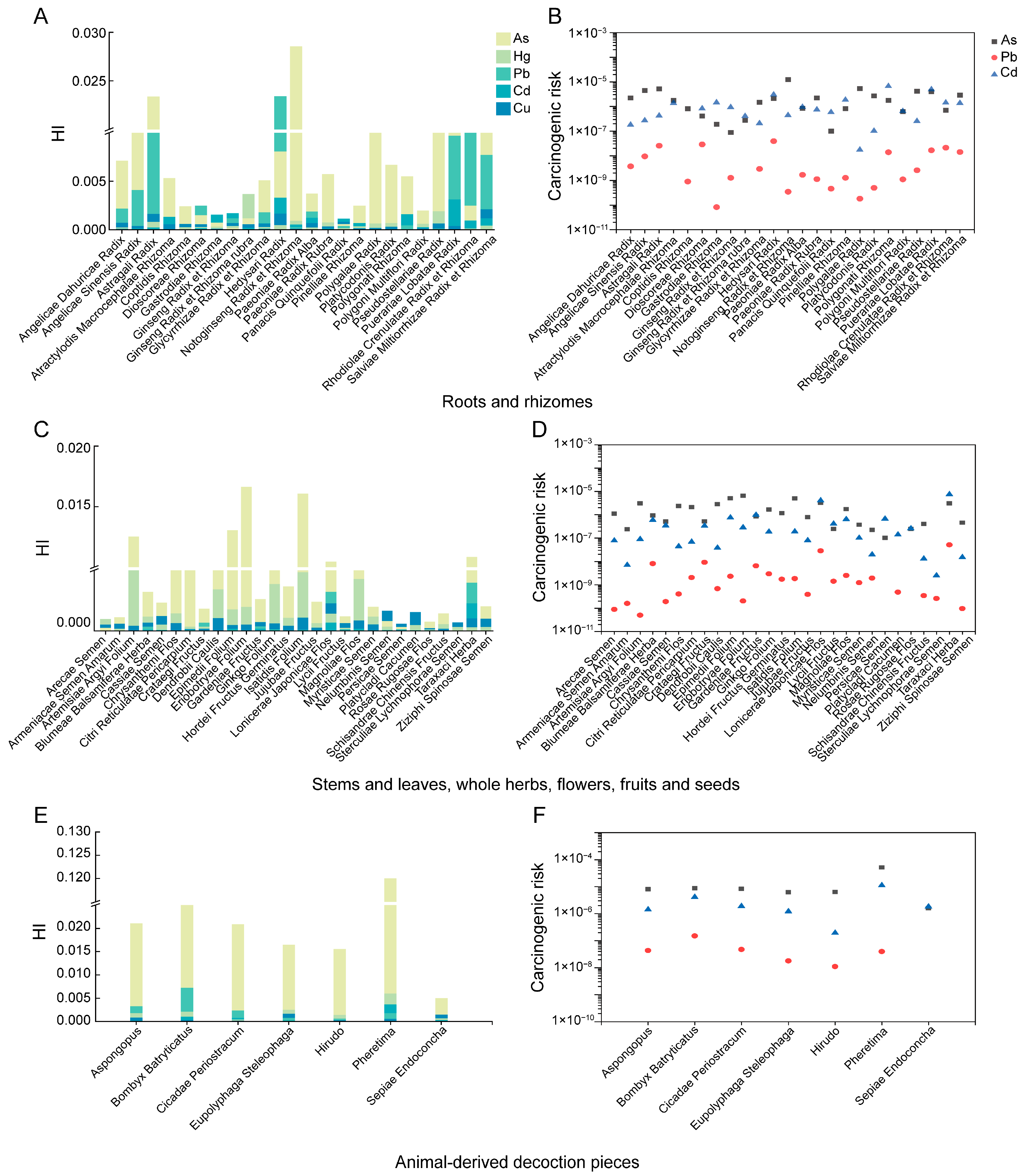

3.4. Health Risk Assessment

3.5. Health Risk Assessment Based on Monte Carlo Simulation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Contamination profiles differed by material type and medicinal part, with animal-derived decoction pieces showing notably higher metal loads. It is recommended that corresponding limit standards be established for all other single-ingredient animal-derived medicinal materials, excluding Sepiae Endoconcha and Hirudo.

- (2)

- Multivariate analyses revealed distinct source patterns: underground and aboveground parts shared similar metal signatures, whereas animal-derived decoction pieces exhibited clearly different profiles.

- (3)

- Key pollutants varied across medicinal parts: As and Hg were more relevant for underground parts, Hg and Cu for aboveground parts, while all five elements required attention in animal-derived decoction pieces.

- (4)

- Health risk assessment indicated generally low risks: The HI values of underground parts, aboveground parts, and animal-derived decoction pieces fell within the ranges of (1.13 × 10−3~2.85 × 10−2), (5.86 × 10−4~1.66 × 10−2), (5.01 × 10−3~1.20 × 10−1), respectively, and all CR values were <1 × 10−4. Sensitivity analysis showed that metal concentrations and daily intake were the main contributors to uncertainty. These findings highlight the importance of controlling metal contamination in raw materials and standardizing dosage to further reduce potential health risks.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. Heavy metal pollution and potential health risks of commercially available Chinese herbal medicines. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.J.; Guan, X.; Chen, Y.J.; Zang, C.X.; Liu, G.H. Strenthening entry-exit supervision for protecting natural resources of traditional Chinese medicine. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2019, 44, 2411–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanahattakij, N.; Kwankhao, P.; Vathesatogkit, P.; Thongmung, N.; Gleebbua, Y.; Sritara, P.; Kitiyakara, C. Herbal or traditional medicine consumption in a Thai worker population: Pattern of use and therapeutic control in chronic diseases. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.J.; Liu, H.; Li, X.M.; Su, B.D.; Xu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.B. Research progress on residual status and risk assessment of exogenous hazardous substances in traditional Chinese medicine. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2023, 54, 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, M.; Kong, D.D.; Ding, S.M.; Yang, M.H. Health risk assessment of exogenous harmful pollutants in Chinese medicine: A review. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2021, 46, 5593–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, C.P. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; Chinese Medicines and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.Y.; Zhang, Q.F. Spatial characterization of dissolved trace elements and heavy metals in the upper Han River (China) using multivariate statistical techniques. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 176, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; You, S.; Zeng, G.; Tan, X.; Hu, X.; Hu, X.; Huang, L.; Li, F. Spatial distribution, health risk assessment and statistical source identification of the trace elements in surface water from the Xiangjiang River, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 9400–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Oleksak, P.; Chrienova, Z.; Wu, Q.; Nepovimova, E.; Zhang, X.; et al. Phytoremediation of heavy metal pollution: Hotspots and future prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 234, 113403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Ramond, A.; O’Keeffe, L.M.; Shahzad, S.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Muka, T.; Gregson, J.; Willeit, P.; Warnakula, S.; Khan, H.; et al. Environmental toxic metal contaminants and risk of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 362, k3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, A.; Luo, C.; Liu, B. Assessing heavy metal contamination in Amomum villosum Lour. fruits from plantations in Southern China: Soil-fungi-plant interactions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.T.; Jin, H.Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Nie, J.; Chen, B.L.; Fang, C.F.; Xue, J.; Bi, X.Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Innovative health risk assessment of heavy metals in Chinese herbal medicines based on extensive data. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaman, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Mise, N.; Sikder, M.T.; Ichihara, G.; Uddin, M.K.; Kurasaki, M.; Ichihara, S. Environmental arsenic exposure and its contribution to human diseases, toxicity mechanism and management. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Gan, C.; He, P.; Liang, Y.; Jin, T.; Zhu, G. Effects of lead and cadmium co-exposure on bone mineral density in a Chinese population. Bone 2014, 63, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zang, J.W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Du, Y.J.; Ban, J.; Wang, Q. Ecological and health risk assessment of cadmium in soil of ten provinces and cities, China. J. Environ. Hyg. 2023, 13, 680–685+695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Yang, L. Mercury-induced toxicity: Mechanisms, molecular pathways, and gene regulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 943, 173577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwan, S.; Ajay, S.K. Effects of heavy metals on soil plants human health and aquatic life. Int. J. Res. Chem. Environ. 2011, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, T.T.; Li, Y.L.; He, H.Z.; Jin, H.Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Gao, F.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.J.; Ma, S.C.; et al. Refined assessment of heavy metal-associated health risk due to the consumption of traditional animal medicines in humans. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Nie, L.X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, N.P.; Lin, R.C. Inorganic elements determination and quality investigation of eupolyphaga. Chin. Pharm. Aff. 2012, 26, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, G.H. Determination and analysis of heavy metals and harmful elements in Pheretima and Hirudo with microwave digestion by ICP-MS. Liaoning J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 45, 2152–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.X.; Kong, D.D.; Li, X.Y.; Fan, Z.W.; Yang, M.H. Pollution level and health risk assessment of heavy metals and hazardous elements in Bombyx Batryticatus. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2019, 44, 5051–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.T.; Jin, H.Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, K.Z.; Kang, S.; Pang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ma, S.C. Safety Evaluation of Heavy Metals and Harmful Elements in Earthworms. Chin. J. Pharmacovigil. 2021, 18, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djahed, B.; Taghavi, M.; Farzadkia, M.; Norzaee, S.; Miri, M. Stochastic exposure and health risk assessment of rice contamination to the heavy metals in the market of Iranshahr, Iran. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 115, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasic Misic, I.D.; Tosic, S.B.; Pavlovic, A.N.; Pecev-Marinkovic, E.T.; Mrmosanin, J.M.; Mitic, S.S.; Stojanovic, G.S. Trace element content in commercial complementary food formulated for infants and toddlers: Health risk assessment. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 132113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, N.; Abass, K.; Khaled, R.; Osaili, T.M.; Semerjian, L. Heavy metals in spices and herbs from worldwide markets: A systematic review and health risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, T.; Liu, C.; Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Deng, F.; An, J.; Feng, L.; Wu, B.; et al. Machine learning and network toxicology reveal arsenic as a key driver of non-carcinogenic health risks from heavy metal residues in Chinese medicinal plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 996, 180143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, K.; Leng, A.; Zhang, L.; Qu, J. Spotlight on the accumulation of heavy metals in Traditional Chinese medicines: A holistic view of pollution status, removal strategies and prospect. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabayati, F.; Hamidian, A.H. Heavy metal pollution in Iranian medicinal plants, a review of sources, distribution, and health implications. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2025, 46, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Xie, Y.M.; Tan, D.; Wang, A.M.; Lan, Y.Y. Determination and evaluation of heavy metals content in Bletilla striata from different sources. Chin. J. Health Lab. Technol. 2015, 25, 471–476. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, D.; Lu, Y.; Chen, P.C.; Xiong, K.; Lan, Y.Y. Analysis of Residues of Heavy Metals and Harmful Elements in Gastrodiae Rhizoma. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2016, 22, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Guan, Q.; Luo, H.; Lin, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, F.; Pan, N.; Yang, Y. Fuzzy synthetic evaluation and health risk assessment quantification of heavy metals in Zhangye agricultural soil from the perspective of sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Liao, X.; Zhou, G.; Huan, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, T. Impact of residential density on heavy metal mobilization in urban soils: Human activity patterns and eco-health risks in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Chen, T.; Zhu, P.; Sun, D.; Wang, W. Assessment of heavy metals contamination and human health risk assessment of the commonly consumed medicinal herbs in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 7345–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, H.; Jia, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, Z.; Fu, S.; Wang, Y. Assessment of Contents and Health Impacts of Four Metals in Chongming Asparagus-Geographical and Seasonal Aspects. Foods 2022, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cai, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. Investigation and probabilistic health risk assessment of trace elements in good sale lip cosmetics crawled by Python from Chinese e-commerce market. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.M.; Shen, M.R.; Jin, H.Y.; Ma, S.C. Exploration of the limit of heavy metals and harmful elements in Chinese medicinal materials and decoction pieces. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 40, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Heavy metal contaminations in herbal medicines: Determination, comprehensive risk assessments, and solutions. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 595335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.G.; He, X.L.; Huang, J.H.; Luo, R.; Ge, H.Z.; Wołowicz, A.; Wawrzkiewicz, M.; Gładysz-Płaska, A.; Li, B.; Yu, Q.X.; et al. Impacts of heavy metals and medicinal crops on ecological systems, environmental pollution, cultivation, and production processes in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 219, 112336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.T.; Zhu, J.; Gao, F.; Wang, J.S.; Song, Q.H.; Wang, H.Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, W.Q.; Kong, D.J.; Guo, Y.S.; et al. Innovative accumulative risk assessment strategy of co-exposure of As and Pb in medical earthworms based on in vivo-in vitro correlation. Environ. Int. 2023, 175, 107933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Wang, P.; Hao, Z.; Gao, Z.; Li, Q.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Feng, F. Ecological and health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and Chinese herbal medicines. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Fan, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Hu, Q.; Cai, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, S. MRTCM: A comprehensive dataset for probabilistic risk assessment of metals and metalloids in traditional Chinese medicine. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. Source Apportionment and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Endemic Tree Species in Southern China: A Case Study of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 911447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.L.; Gwo, J.C.; Wang, G.S.; Chen, C.Y. Distribution of feminizing compounds in the aquatic environment and bioaccumulation in wild tilapia tissues. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 11349–11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Nie, L.X.; Shen, M.R.; Liu, L.N.; Yu, J.D.; Jin, H.Y.; Wei, F.; Ma, S.C. Technical guidelines for risk assessment of heavy metals in traditional Chinese medicines. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.M.; Chien, M.Y.; Chao, P.C.; Huang, C.M.; Chen, C.H. Investigation of toxic heavy metals content and estimation of potential health risks in Chinese herbal medicine. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.T.; Shen, M.R.; Zhang, L.; Jin, H.Y.; Ma, S.C. Formulation of limit standards for heavy metals and harmful elements in TCMs and related reflections. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 43, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiminicesei, D.M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Impact of Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment on the Metabolic Profile of Medicinal Plants and Their Therapeutic Potential. Plants 2024, 13, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Suo, Z.F.; Ma, Z.Y.; Ma, M.Q.; Li, J.X.; Zhu, M.L. Health risk of five common heavy metals exposure based on astragalus membranaceus ingestion. J. Mod. Med. Health 2018, 34, 3287–3289. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.P.; Wang, S.; Zhan, Z.W.; He, D. Heavy metal dynamics in riverine mangrove systems: A case study on content, migration, and enrichment in surface sediments, pore water, and plants in Zhanjiang, China. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 203, 106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, J.; Sun, H.; Qin, J.; Yang, J. Metals in Traditional Chinese medicinal materials (TCMM): A systematic review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.Q.; Xiao, L.; Wang, B.; Zhu, H.L.; Nie, J. Residue analysis and risk assessment of heavy metals and harmful elements in 37 plant medicinal materials. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 41, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.S.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, L.; Khan, A.; Mateen, A.; Jahan, S.; Ullah, U.; AlMasoud, N.; Alomar, T.S.; Rauf, A.; et al. Quantification of toxic heavy metals, trace elements and essential minerals contents in traditional herbal medicines commonly utilized in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.F.; Althbah, A.I.; Mohammed, A.H.; Alrasheed, M.A.; Ismail, M.; Allemailem, K.S.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Alkhalifah, A. Microbial and heavy metal contamination in herbal medicine: A prospective study in the central region of Saudi Arabia. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Lu, J.; Qin, Y.; Mo, Y.; Xiao, P.; Liu, Y. Identification of the heavy metal pollution sources in the rhizosphere soil of farmland irrigated by the Yellow River using PMF analysis combined with multiple analysis methods-using Zhongwei city, Ningxia, as an example. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 16203–16214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.Y.; Liang, X.X. Study on the excessive heavy metals in traditional Chinese Medicine. Guangxi J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 44, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Proshad, R.; Islam, M.S.; Kormoker, T.; Sayeed, A.; Khadka, S.; Idris, A.M. Potential toxic metals (PTMs) contamination in agricultural soils and foodstuffs with associated source identification and model uncertainty. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, E.; Yan, M.; Zheng, S.; Fan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J. Contamination and source apportionment of metals in urban road dust (Jinan, China) integrating the enrichment factor, receptor models (FA-NNC and PMF), local Moran’s index, Pb isotopes and source-oriented health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: Environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.X.; Huang, Q.Q.; Li, S.N.; Han, L.Y.; Li, H.F.; Su, D.C.; Qiao, Y.H. Analysis of copper source in farmland soil and threshold study for soil pollution control. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2014, 9, 774–784. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimzadeh, G.; Omer, A.K.; Naderi, M.; Sharafi, K. Human health risk assessment of potentially toxic and essential elements in medicinal plants consumed in Zabol, Iran, using the Monte Carlo simulation method. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.X.; Liu, W.J.; Qiu, R.L. Research Progress and Prospects of Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution in Farmland Soils of China. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar]

- de Conti, A.; Madia, F.; Schubauer-Berigan, M.K.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L. Carcinogenicity of some metals evaluated by the IARC Monographs: A synopsis of the evaluations of arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, and antimony. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 504, 117506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, G.; Yan, Z. Status and environmental management of soil mercury pollution in China: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PTEs | Statistical Indicators | Overall | Roots and Rhizomes | Stems and Leaves, Whole Herbs, Flowers, Fruits and Seeds | Animal-Derived Decoction Pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | range (mg·kg−1) | 0–27.2 | 0–7.09 | 0–1.54 | 0.07–27.18 |

| mean ± sd | 0.78 ± 2.17 | 0.37 ± 0.77 ** | 0.21 ± 0.31 *** | 3.03 ± 4.35 | |

| detection rate (%) | 82.70% | 84.20% | 73.50% | 100.00% | |

| exceedance rate (%) | 8.30% | 2.30% | 0.00% | 41.30% | |

| Hg | range (mg·kg−1) | 0–1.02 | 0–0.29 | 0–1.02 | 0–1.00 |

| mean ± sd | 0.067 ± 0.136 | 0.03 ± 0.05 ** | 0.07 ± 0.14 | 0.15 ± 0.22 | |

| detection rate (%) | 72.00% | 57.60% | 76.50% | 96.00% | |

| exceedance rate (%) | 8.10% | 1.70% | 8.80% | 24.00% | |

| Pb | range (mg·kg−1) | 0–55.0 | 0–4.10 | 0–13.0 | 0–55.0 |

| mean ± sd | 1.06 ± 4.19 | 0.33 ± 0.71 | 0.33 ± 1.13 ** | 4.45 ± 9.03 | |

| detection rate (%) | 63.50% | 55.90% | 58.20% | 93.30% | |

| exceedance rate (%) | 4.70% | 0.00% | 0.60% | 25.30% | |

| Cd | range (mg·kg−1) | 0–4.11 | 0–1.10 | 0–0.96 | 0–4.11 |

| mean ± sd | 0.125 ± 0.360 | 0.08 ± 0.16 *** | 0.06 ± 0.15 # | 0.38 ± 0.74 | |

| detection rate (%) | 63.00% | 55.90% | 56.50% | 94.70% | |

| exceedance rate (%) | 1.40% | 1.70% | 0.00% | 6.70% | |

| Cu | range(mg·kg−1) | 0–49.20 | 0–49.20 | 0–43.4 | 0.23–43.9 |

| mean ± sd | 8.98 ± 7.20 | 7.06 ± 5.86 ** | 8.72 ± 6.49 | 14.1 ± 9.04 | |

| detection rate (%) | 90.50% | 84.80% | 92.40% | 100.00% | |

| exceedance rate (%) | 7.80% | 2.30% | 5.90% | 25.30% |

| Parameters | Roots and Rhizomes-HI Contribution % | Stems and Leaves, Whole Herbs, Flowers, Fruits and Seeds-HI Contribution % | Animal-Derived Decoction Pieces-HI Contribution % | Roots and Rhizomes-CR Contribution % | Stems and Leaves, Whole Herbs, Flowers, Fruits and Seeds-CR Contribution % | Animal-Derived Decoction Pieces-CR Contribution % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 61.0% | 69.4% | 60.7% | 48.2% | 72.3% | 51.8% |

| Hg | 2.5% | 10.4% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Pb | 1.2% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Cd | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 19.3% | 18.8% | 2.7% |

| Cu | 0.3% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| IR | 23.6% | 7.9% | 20.7% | 21.6% | 3.8% | 24.1% |

| EF | 9.5% | 8.5% | 15.4% | 9.3% | 4.2% | 18.1% |

| BW | 1.7% | 1.5% | 3.0% | 1.6% | 0.9% | 3.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, J.; Huang, D.; Ma, X.; Zhu, D.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. Potentially Toxic Elements Accumulation and Health Risk Evaluation in Different Parts of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials. Toxics 2026, 14, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010040

Pan J, Huang D, Ma X, Zhu D, Lu Y, Liu C, Zheng L, Li Y, Sun J. Potentially Toxic Elements Accumulation and Health Risk Evaluation in Different Parts of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010040

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Jie, Di Huang, Xue Ma, Di Zhu, Yuan Lu, Chunhua Liu, Lin Zheng, Yongjun Li, and Jia Sun. 2026. "Potentially Toxic Elements Accumulation and Health Risk Evaluation in Different Parts of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials" Toxics 14, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010040

APA StylePan, J., Huang, D., Ma, X., Zhu, D., Lu, Y., Liu, C., Zheng, L., Li, Y., & Sun, J. (2026). Potentially Toxic Elements Accumulation and Health Risk Evaluation in Different Parts of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials. Toxics, 14(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010040