Manganese Exposure Is Associated with Reduced Grip Strength: Evidence from Humans and Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Epidemiological Study

2.1.1. Study Population

2.1.2. Urinary Mn Measurement

2.1.3. Hand Grip Strength

2.1.4. Covariates

2.2. Animal Study

2.2.1. Animals and Treatment

2.2.2. Forelimb Grip Strength

2.2.3. Triceps Isolation and Mn Determination

2.2.4. qRT-PCR Assay

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

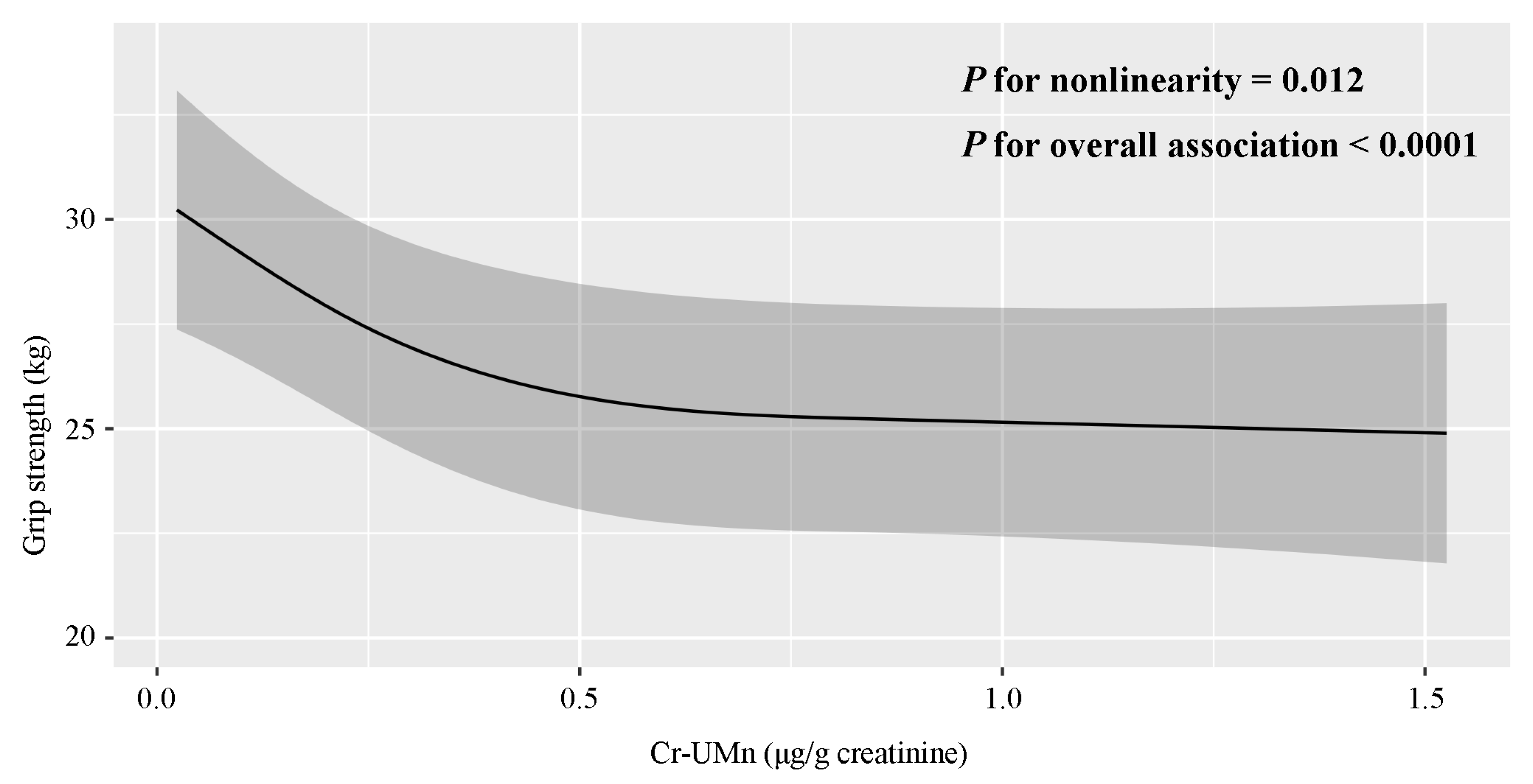

3.1. Epidemiological Study

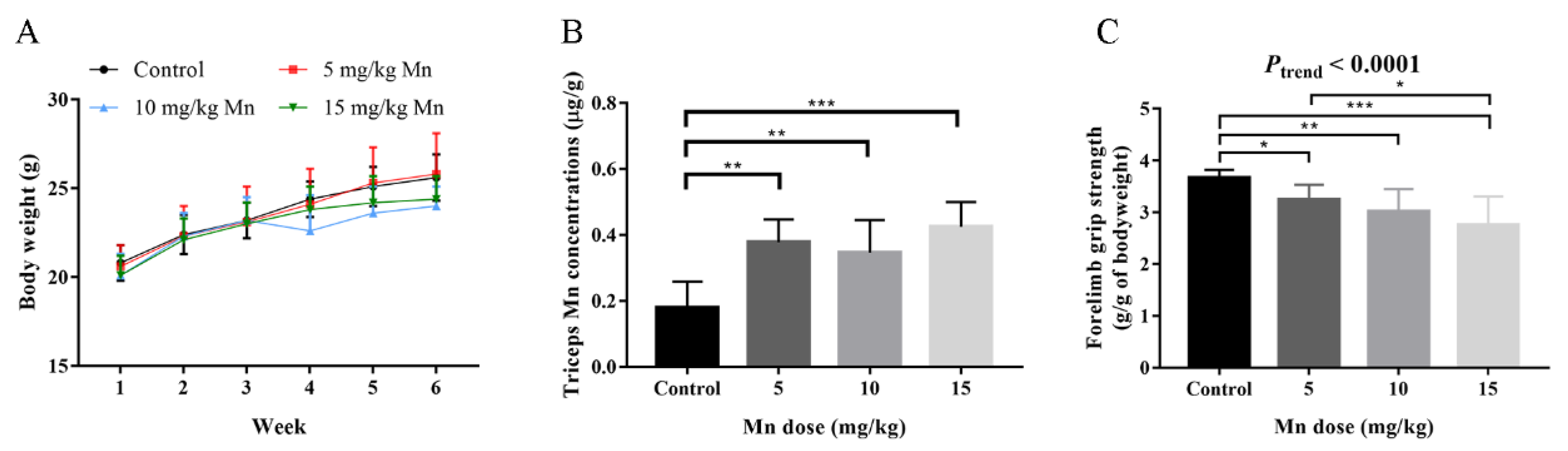

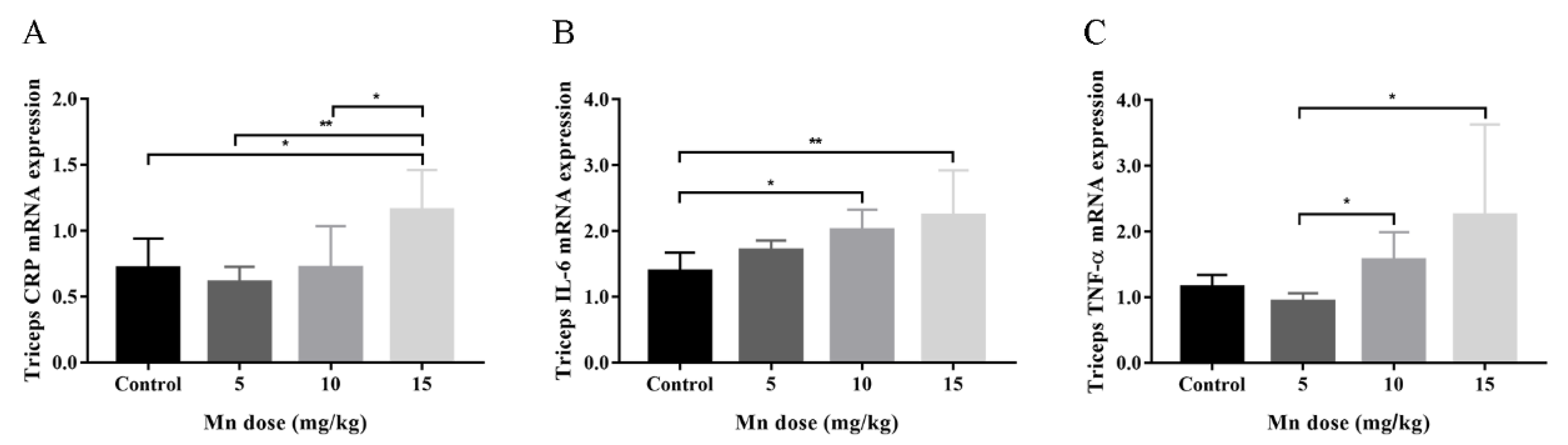

3.2. Animal Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-Olmo, I.; Mantecón, P.; Markiv, B.; Ruiz-Azcona, L.; Santibáñez, M. A Review on the Environmental Exposure to Airborne Manganese, Biomonitoring, and Neurological/Neuropsychological Outcomes. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 254, 85–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L. A review of pollution status and countermeasures of heavy metal pollution in Guangxi Manganese mining areas. Energy Environ. Prot. 2021, 35, 1–5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, L. Current Status and Technological Advances in Development and Utilization of Manganese Resources. China’s Manganese Ind. 2024, 42, 16–21+26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Agustín, R.; Rodríguez-Agudelo, Y.; Schilmann, A.; Solís-Vivanco, R.; Montes, S.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Cortez-Lugo, M.; Ríos, C. Effect of environmental manganese exposure on verbal learning and memory in Mexican children. Environ. Res. 2013, 121, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, M.F.; Sauvé, S.; Barbeau, B.; Legrand, M.; Brodeur, M.; Bouffard, T.; Limoges, E.; Bellinger, D.C.; Mergler, D. Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Filho, J.A.; Novaes Cde, O.; Moreira, J.C.; Sarcinelli, P.N.; Mergler, D. Elevated manganese and cognitive performance in school-aged children and their mothers. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, R.G.; Guazzetti, S.; Zoni, S.; Donna, F.; Peter, S.; Zacco, A.; Salmistraro, M.; Bontempi, E.; Zimmerman, N.J.; Smith, D.R. Tremor, olfactory and motor changes in Italian adolescents exposed to historical ferro-manganese emission. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergler, D.; Huel, G.; Bowler, R.; Iregren, A.; Bélanger, S.; Baldwin, M.; Tardif, R.; Smargiassi, A.; Martin, L. Nervous system dysfunction among workers with long-term exposure to manganese. Environ. Res. 1994, 64, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergler, D.; Baldwin, M. Early manifestations of manganese neurotoxicity in humans: An update. Environ. Res. 1997, 73, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Agudelo, Y.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Ríos, C.; Rosas, I.; Sabido Pedraza, E.; Miranda, J.; Siebe, C.; Texcalac, J.L.; Santos-Burgoa, C. Motor alterations associated with exposure to manganese in the environment in Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.J.; Rong, J.H.; Wang, X.X.; Cai, J.S.; Qin, L.D.; Liu, Q.M.; Tang, X.; Mo, X.T.; Wei, Y.F.; Lin, Y.X.; et al. Correlation between Combined Urinary Metal Exposure and Grip Strength under Three Statistical Models: A Cross-sectional Study in Rural Guangxi. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2024, 37, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbemavo, M.C.J.; Bouchard, M.F. Concentrations of Lead, Mercury, Selenium, and Manganese in Blood and Hand Grip Strength among Adults Living in the United States (NHANES 2011–2014). Toxics 2021, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Shu, Y.; Wang, Y. Exposure to mixture of heavy metals and muscle strength in children and adolescents: A population-based study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 60269–60277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, C.A.; Ward, D.L.; Klein, B.G. Basal Ganglia accumulation and motor assessment following manganese chloride exposure in the C57BL/6 mouse. Int. J. Toxicol. 2005, 24, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Dodd, C.A.; Hekmatyar, S.K.; Filipov, N.M. Brain deposition and neurotoxicity of manganese in adult mice exposed via the drinking water. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkpaa, K.W.; Nkpaa, B.B.; Amadi, B.A.; Ogbolosingha, A.J.; Wopara, I.; Belonwu, D.C.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Nwaichi, E.O.; Wegwu, M.O.; Orisakwe, O.E. Selenium abates manganese-induced striatal and hippocampal toxicity via abrogation of neurobehavioral deficits, biometal accumulation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and caspase-3 activation in rats. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Pirlich, M. Hand grip strength: Outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.A.; Kirkwood, T.B.L. Grip strength and mortality: A biomarker of ageing? Lancet 2015, 386, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.M.; Syddall, H.E.; Cooper, R.; Benzeval, M.; Deary, I.J.; Dennison, E.M.; Der, G.; Gale, C.R.; Inskip, H.M.; Jagger, C.; et al. Grip strength across the life course: Normative data from twelve British studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavasini, R.; Serenelli, M.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Gray, S.R.; Izawa, K.P.; Watanabe, S.; Colin-Ramirez, E.; Castillo-Martínez, L.; Izumiya, Y.; Hanatani, S.; et al. Grip strength predicts cardiac adverse events in patients with cardiac disorders: An individual patient pooled meta-analysis. Heart 2019, 105, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Piasecki, M.; Atherton, P.J. The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: Measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, R.; Robinson-Lane, S.G.; Cook, S.; Clark, B.C.; Herrmann, S.; O’Connor, M.L.; Hackney, K.J. Handgrip Strength Is Associated with Poorer Cognitive Functioning in Aging Americans. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 70, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taekema, D.G.; Gussekloo, J.; Maier, A.B.; Westendorp, R.G.; de Craen, A.J. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.A.; Welsh, P.; Lyall, D.M.; Steell, L.; Petermann, F.; Anderson, J.; Iliodromiti, S.; Sillars, A.; Graham, N.; Mackay, D.F.; et al. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer outcomes and all cause mortality: Prospective cohort study of half a million UK Biobank participants. BMJ 2018, 361, k1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, B.H.; Cooper, R.; Bergland, A.; Jørgensen, L.; Schirmer, H.; Skirbekk, V.; Emaus, N. The association of grip strength from midlife onwards with all-cause and cause-specific mortality over 17 years of follow-up in the Tromsø Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Guo, F.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Guan, T.; Yao, Y.; Lv, X.; Xue, T. Association Between Ambient Fine Particulate Matter and Physical Functioning in Middle-Aged and Older Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Lee, M.R.; Choi, Y.H.; Hwang, H.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, C.; Hong, Y.C. Association between phthalate exposure and lower handgrip strength in an elderly population: A repeated-measures study. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esquinas, E.; Carrasco-Rios, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Ortolá, R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Cadmium exposure is associated with reduced grip strength in US adults. Environ. Res. 2020, 180, 108819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-N.; Lee, M.-R.; Choi, Y.-H.; Lee, B.-E.; Hong, Y.-C. Associations of Blood Cadmium Levels With Depression and Lower Handgrip Strength in a Community-Dwelling Elderly Population: A Repeated-Measures Panel Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2016, 71, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, K.M.; Aschner, M. Manganese: Its Role in Disease and Health. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2019, 19, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Streifel, K.M.; Sullivan, K.A.; Legare, M.E.; Tjalkens, R.B. Developmental exposure to manganese increases adult susceptibility to inflammatory activation of glia and neuronal protein nitration. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 112, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkpaa, K.W.; Onyeso, G.I.; Kponee, K.Z. Rutin abrogates manganese-Induced striatal and hippocampal toxicity via inhibition of iron depletion, oxidative stress, inflammation and suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 53, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Song, J.; Zheng, Z.; Guan, H.; Nan, X.; Zhang, N. Effects of Excess Manganese on the Oxidative Status, and the Expression of Inflammatory Factors and Heat Shock Proteins in Cock Kidneys. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 197, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, C.S.L.; Thang, L.A.N.; Maier, A.B. Markers of inflammation and their association with muscle strength and mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; He, M.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; Lu, G.; et al. Relation between cadmium body burden and cognitive function in older men: A cross-sectional study in China. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Qin, J.; Wei, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y. Influence of manganese exposure on cognitive function, plasma APP and Aβ levels in older men. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 67, 126788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Caulfield, M. Hypertension. Lancet 2015, 386, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur Clark, J.A.; Sun, D. Guidelines for the ethical review of laboratory animal welfare People’s Republic of China National Standard GB/T 35892-2018 [Issued 6 February 2018 Effective from 1 September 2018]. Animal Model. Exp. Med. 2020, 3, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadrozniak, A.; Wojda, E.; Wlaź, A.; Łuszczki, J.J. Characterization of acute adverse-effect profiles of selected antiepileptic drugs in the grip-strength test in mice. Pharmacol. Rep. 2009, 61, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Morales, M.; Li, N.; Fritz, A.G.; Ruobing, R.; Blaeser, A.; Francois, E.; Lu, Q.L.; Nagaraju, K.; Spurney, C.F. Skeletal, cardiac, and respiratory muscle function and histopathology in the P448Lneo- mouse model of FKRP-deficient muscular dystrophy. Skelet. Muscle 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Woo, J.G.; Zhang, N. Association between urinary manganese and blood pressure: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2011–2014. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, C.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Y. Handgrip strength is positively related to blood pressure and hypertension risk: Results from the National Health and nutrition examination survey. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilnikova, N.; Karyakina, N.; Farhat, N.; Ramoju, S.; Cline, B.; Momoli, F.; Mattison, D.; Jensen, N.; Terrell, R.; Krewski, D. Biomarkers of environmental manganese exposure. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2022, 52, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Long, L.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Mo, X.; Lu, J.; Fu, X.; Li, W.; Liu, S.; et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and manganese concentrations in red blood cells of smelting workers: Search for biomarkers of manganese exposure. Neurotoxicology 2007, 28, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewski, M.; Piwko, K.; Ordak, M.; Muszynska, E.; Nasierowski, T.; Bujalska-Zadrozny, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Manganism: A Narrative Review and Laboratory Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratesi, A.; Vella, A.; Pasini, E.; Salvi, F.; Mascalchi, M. Parkinsonism in polycythaemia vera probably due to manganism. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2420–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Tan, R.; Zhong, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. The non-linear associations between blood manganese level and sarcopenia in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 84, 127465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschner, J.L.; Aschner, M. Nutritional aspects of manganese homeostasis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005, 26, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, K.J.; Caito, S.W.; Tipps, K.G.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Manganese Is Essential for Neuronal Health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2015, 35, 71–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Villalba, I.; Lacasaña, M.; Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Hernández, A.F.; Gonzalez-Alzaga, B.; Aguilar-Garduño, C.; Gil, F. Biomonitoring of arsenic, cadmium, lead, manganese and mercury in urine and hair of children living near mining and industrial areas. Chemosphere 2015, 124, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisse, C.; Tagne-Fotso, R.; Howsam, M.; Richeval, C.; Labat, L.; Leroyer, A. Blood and urinary levels of metals and metalloids in the general adult population of Northern France: The IMEPOGE study, 2008–2010. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yang, A.; Cheng, N.; Huang, W.; Huang, P.; Liu, N.; Bai, Y. Sex-specific associations of blood and urinary manganese levels with glucose levels, insulin resistance and kidney function in US adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2011–2016. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 126940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, K.; Wei, X.; Zhou, T.; Liu, D.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, L.; et al. Environmental exposure to metals and the risk of hypertension: A cross-sectional study in China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, W.L.; Wang, C.W.; Wu, D.W.; Chen, S.C.; Hung, C.H.; Kuo, C.H. Associations of Heavy Metals with Metabolic Syndrome and Anthropometric Indices. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ou, Y.L.; Liu, Y.Q.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Q.F.; Wu, Q.; Fan, T.Q.; Yan, L.L.; Wang, J.Y. Correlations of trace element levels in the diet, blood, urine, and feces in the Chinese male. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 145, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle-McFarland, D.; Liu, Y.; Mostafaei, F.; Zauber, S.E.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, Q.; Zheng, W.; Nie, L.H.; Wells, E.M. The association of bone and blood manganese with motor function in Chinese workers. Neurotoxicology 2022, 88, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.; Mergler, D.; Baldwin, M.E.; Panisset, M. Manganese cumulative exposure and symptoms: A follow-up study of alloy workers. Neurotoxicology 2008, 29, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblith, E.S.; Casey, S.L.; Lobdell, D.T.; Colledge, M.A.; Bowler, R.M. Environmental exposure to manganese in air: Tremor, motor and cognitive symptom profiles. Neurotoxicology 2018, 64, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Chu, N.S.; Lu, C.S.; Chen, R.S.; Calne, D.B. Long-term progression in chronic manganism: Ten years of follow-up. Neurology 1998, 50, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Li, D.; Wei, S.; Yang, J.; Tang, C.; Ma, X.; Zou, Y. Long noncoding RNA Sh2d3c promotes manganese-induced neuronal apoptosis through the mmu-miR-675-5p/Chmp4b/Bax axis. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 365, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Gan, D.; Yang, X.; Zou, Y. Manganese modifies Neurotrophin-3 (NT3) and its tropomyosin receptor kinase C (TrkC) in the cortex: Implications for manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 135, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1379–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belizário, J.E.; Fontes-Oliveira, C.C.; Borges, J.P.; Kashiabara, J.A.; Vannier, E. Skeletal muscle wasting and renewal: A pivotal role of myokine IL-6. Springerplus 2016, 5, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.J.; Patel, B.M. TNF-α and cancer cachexia: Molecular insights and clinical implications. Life Sci. 2017, 170, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirakawa, T.; Rojasawasthien, T.; Inoue, A.; Matsubara, T.; Kawamoto, T.; Kokabu, S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha regulates myogenesis to inhibit differentiation and promote proliferation in satellite cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 580, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lin, S.; Chen, W.; Lian, G.; Wu, W.; Chen, A.; Sagor, M.I.H.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Xie, L. TNF-α contributes to sarcopenia through caspase-8/caspase-3/GSDME-mediated pyroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H. Regulation of C-reactive protein conformation in inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, W.; Xue, X.; Wang, Q.; Han, L.; Li, W.; Lv, S.; Liu, D.; Richards, J.; Shen, Z.; et al. Presence of multimeric isoforms of human C-reactive protein in tissues and blood. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 5461–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.Y.; Peng, J.C.; Xie, B.Y.; Qin, W.X.; Aschner, M.; Ou, S.Y.; Jiang, Y.M. Effects of combined exposure of manganese and iron on serum inflammatory factor levels among workers. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 9603271241293112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, N.Y.; Krakauer, J.C. Association of Body Shape Index (ABSI) with Hand Grip Strength. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Pang, Y.; Huo, W.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, R.; Wang, B. Association Between Chronic Exposure to Tobacco Smoke and Accumulation of Toxic Metals in Hair Among Pregnant Women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 185, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, S.; Al-Sayegh, N.; Nadar, M. Smoking impact on grip strength and fatigue resistance: Implications for exercise and hand therapy practice. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Jeong, J.Y.; Kim, D.H. The Relationship between Smoking, Socioeconomic Status and Grip Strength among Community-dwelling Elderly Men in Korea: Hallym Aging Study. Epidemiol. Health 2013, 35, e2013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Miyatake, N.; Sakano, N.; Oda, K.; Katayama, A.; Nishii, K.; Numata, T. Relationship between cigarette smoking and muscle strength in Japanese men. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2012, 45, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esquinas, E.; Téllez-Plaza, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Ortolá, R.; Olmedo, P.; Gil, F.; López-García, E.; Navas-Acien, A.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Blood cadmium and physical function limitations in older adults. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD or No. (%) | Mn (μg/g Creatinine) a | p-Value | Hand Grip Strength (kg) a | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 375 (100.00) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.42) | 28.1 (22.3, 33.6) | ||

| Age (years) | 66.03 ± 3.92 | 0.529 | <0.0001 | ||

| 60–64 | 156 (41.60) | 0.23 (0.13, 0.41) | 29.8 (24.7, 35.2) | ||

| 65–69 | 138 (36.80) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.40) | 28.2 (22.3, 32.3) | ||

| ≥70 | 81 (21.60) | 0.23 (0.16, 0.49) | 25.2 (20.5, 29.3) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.342 | 0.636 | |||

| Han | 28 (7.47) | 0.30 (0.14, 0.71) | 28.2 (24.8, 35.0) | ||

| Zhuang | 340 (90.67) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.39) | 28.2 (22.3, 33.6) | ||

| Other | 7 (1.87) | 0.24 (0.19, 0.38) | 23.0 (22.0, 33.3) | ||

| Marital status | 0.032 | 0.065 | |||

| Married | 331 (88.27) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.37) | 28.4 (22.5, 33.9) | ||

| Other | 44 (11.73) | 0.36 (0.14, 0.71) | 26.6 (20.6, 31.8) | ||

| Education level | 0.194 | <0.0001 | |||

| No formal education | 36 (9.60) | 0.27 (0.17, 0.36) | 27.6 (21.0, 30.2) | ||

| 1–6 years of education | 155 (41.33) | 0.22 (0.15, 0.43) | 26.5 (20.8, 31.6) | ||

| >6 years of education | 184 (49.07) | 0.21 (0.12, 0.40) | 29.8 (24.6, 35.0) | ||

| Occupation | 0.029 | 0.708 | |||

| Farmer | 316 (84.27) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.44) | 28.1 (22.5, 33.5) | ||

| Non-farmer | 59 (15.73) | 0.19 (0.09, 0.31) | 27.7 (21.6, 34.5) | ||

| Household income (RMB/year) | 0.604 | 0.391 | |||

| <10,000 | 147 (39.20) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.42) | 28.3 (22.5, 33.7) | ||

| 10,000–30,000 | 82 (21.87) | 0.24 (0.13, 0.49) | 27.5 (21.8, 31.9) | ||

| ≥30,000 | 146 (38.93) | 0.21 (0.14, 0.37) | 28.6 (22.4, 34.2) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.69 ± 2.86 | 0.098 | 0.010 | ||

| <18.5 | 44 (11.73) | 0.20 (0.13, 0.28) | 25.5 (20.0, 29.8) | ||

| 18.5–23.9 | 257 (68.53) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.48) | 28.0 (22.3, 33.4) | ||

| ≥24.0 | 74 (19.73) | 0.21 (0.13, 0.37) | 30.1 (24.6, 34.8) | ||

| Tobacco smoking | 0.902 | 0.635 | |||

| No | 199 (53.07) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.43) | 28.0 (22.3, 33.2) | ||

| Yes | 176 (46.93) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.39) | 28.2 (22.4, 33.9) | ||

| Alcohol drinking | 0.212 | 0.235 | |||

| No | 168 (44.80) | 0.21 (0.13, 0.39) | 28.8 (22.9, 33.7) | ||

| Yes | 207 (55.20) | 0.24 (0.14, 0.42) | 27.6 (21.9, 33.3) | ||

| Farm-work | 0.144 | 0.240 | |||

| No | 107 (28.53) | 0.21 (0.11, 0.37) | 27.9 (22.3, 32.0) | ||

| Yes | 268 (71.47) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.44) | 28.2 (22.3, 34.2) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.529 | 0.879 | |||

| No | 140 (37.33) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.39) | 28.0 (22.2, 33.7) | ||

| Yes | 235 (62.67) | 0.22 (0.13, 0.42) | 28.2 (22.4, 33.5) |

| Urinary Mn (μg/g Creatinine) | Model A a | Model B b | Model C c | Model D d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | |

| T1 (<0.17) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| T2 (0.17–0.33) | −3.60 (−5.71, −1.48) | −3.36 (−5.42, −1.30) | −3.41 (−5.46, −1.37) | −3.33 (−5.39, −1.27) |

| T3 (≥0.33) | −3.91 (−6.02, −1.79) | −3.58 (−5.65, −1.51) | −3.73 (−5.79, −1.67) | −3.57 (−5.68, −1.47) |

| p-trend | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, P.; Tang, C.; Wei, S.; Lu, W.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Liang, G.; Wang, J.; Peng, Y.; et al. Manganese Exposure Is Associated with Reduced Grip Strength: Evidence from Humans and Mice. Toxics 2026, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010031

Fang P, Tang C, Wei S, Lu W, Liu S, Ma X, Zhang L, Liang G, Wang J, Peng Y, et al. Manganese Exposure Is Associated with Reduced Grip Strength: Evidence from Humans and Mice. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Peiyu, Chuanqiao Tang, Shengtao Wei, Wenmin Lu, Shaohui Liu, Xiaoli Ma, Li’e Zhang, Guiqiang Liang, Jian Wang, Yang Peng, and et al. 2026. "Manganese Exposure Is Associated with Reduced Grip Strength: Evidence from Humans and Mice" Toxics 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010031

APA StyleFang, P., Tang, C., Wei, S., Lu, W., Liu, S., Ma, X., Zhang, L., Liang, G., Wang, J., Peng, Y., & Zou, Y. (2026). Manganese Exposure Is Associated with Reduced Grip Strength: Evidence from Humans and Mice. Toxics, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010031