Glyphosate as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant and Its Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

3. Results

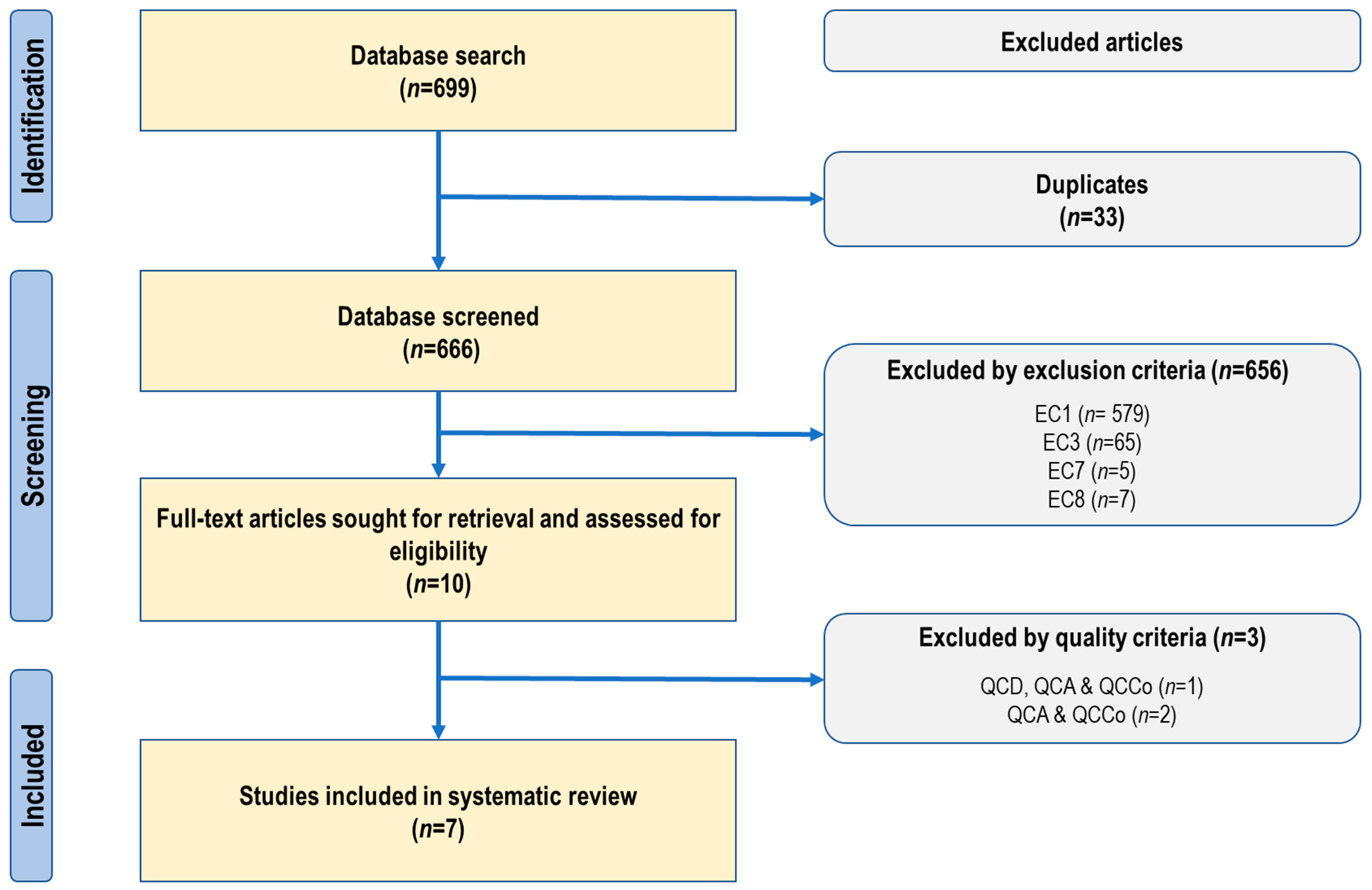

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

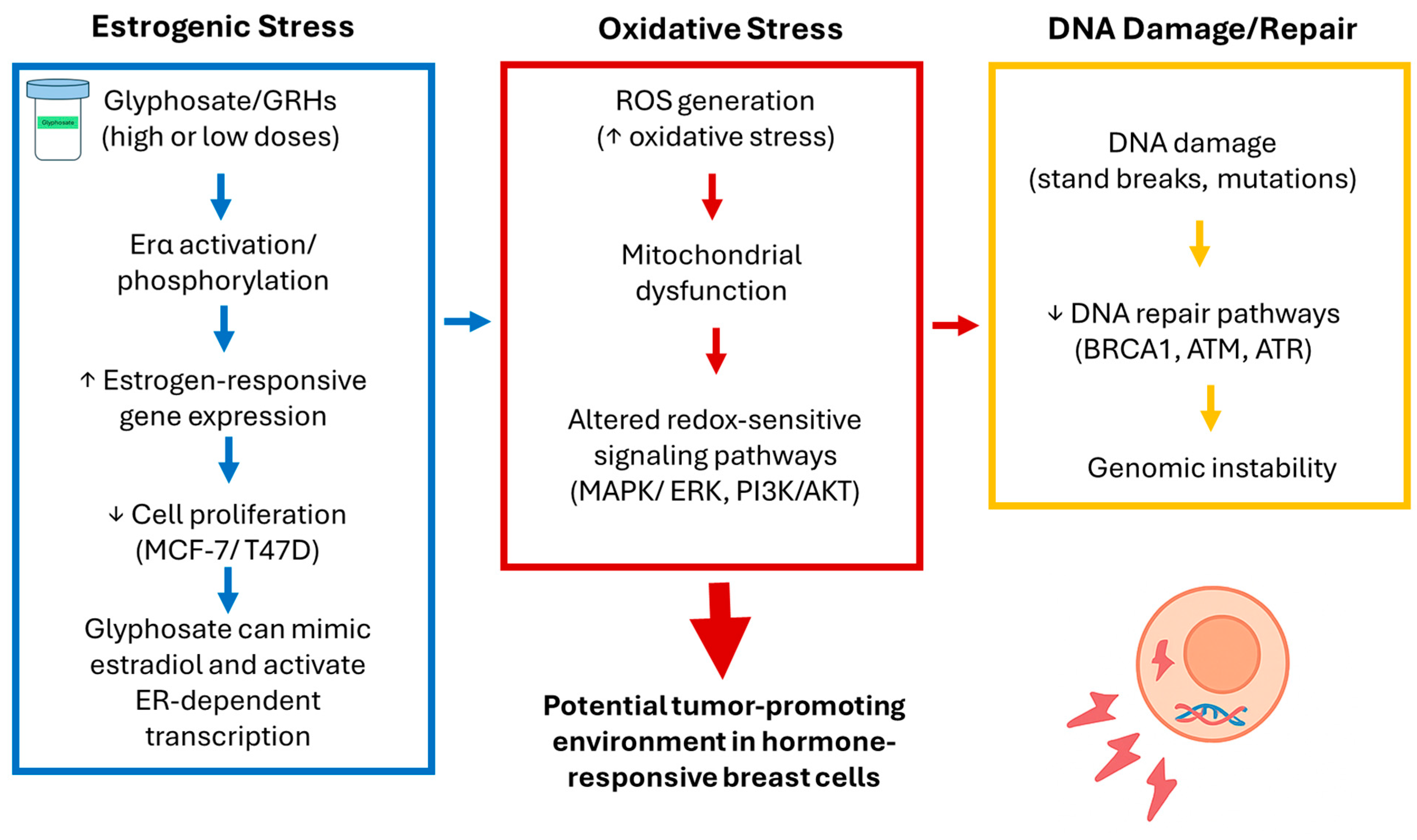

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBHs | Glyphosate-Based Herbicide Formulations |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register Of Systematic Reviews Only |

| SRL | Systematic Literature Review |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| PECO | Population, Exposure, Comparator, and Outcomes |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| IC | Inclusion Criteria |

| EC | Exclusion Criteria |

| QCD | Quality Criteria Design |

| QCC | Quality Criteria Conduct |

| QCA | Quality Criteria Analysis |

| QCCo | Quality Criteria of Conclusion |

| MTT | Metil Thiazolyl Tetrazolium |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| ERE | Estrogen Response Element |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Benbrook, C.M. Trends in Glyphosate Herbicide Use in the United States and Globally. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2016, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlaeys, A.; Dubuisson, F.; Seralini, G.E.; Travert, C. Formulants of Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Have More Deleterious Impact than Glyphosate on TM4 Sertoli Cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2018, 52, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Montanarella, L.; Jones, A.; Fernández-Ugalde, O.; Mol, H.G.J.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Distribution of Glyphosate and Aminomethylphosphonic Acid (AMPA) in Agricultural Topsoils of the European Union. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curwin, B.D.; Hein, M.J.; Sanderson, W.T.; Nishioka, M.G.; Reynolds, S.J.; Ward, E.M.; Alavanja, M.C. Pesticide Contamination inside Farm and Nonfarm Homes. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2005, 2, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillezeau, C.; van Gerwen, M.; Shaffer, R.M.; Rana, I.; Zhang, L.; Sheppard, L.; Taioli, E. The Evidence of Human Exposure to Glyphosate: A Review. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2017.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowska, B.; Woźniak, E.; Sicińska, P.; Mokra, K.; Michałowicz, J. Glyphosate Disturbs Various Epigenetic Processes in vitro and in vivo—A Mini Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuryk, J.; Klepacka, K.; Kutner, W.; Sharma, P.S. Glyphosate: Hepatotoxicity, Nephrotoxicity, Hemotoxicity, Carcinogenicity, and Clinical Cases of Endocrine, Reproductive, Cardiovascular, and Pulmonary System Intoxication. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Deng, Q.; Hu, H.; Liu, M.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Lu, Z.; Young, K.H.; Ma, X.; et al. Glyphosate Induces Benign Monoclonal Gammopathy and Promotes Multiple Myeloma Progression in Mice. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Rana, I.; Shaffer, R.M.; Taioli, E.; Sheppard, L. Exposure to Glyphosate-Based Herbicides and Risk for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Meta-Analysis and Supporting Evidence. Mutat. Res. 2019, 781, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenburger, D.D. A Review and Update with Perspective of Evidence That the Herbicide Glyphosate (Roundup) Is a Cause of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021, 21, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, T.; Trinchese, G.; Leandri, R.; De Falco, M.; Mollica, M.P.; Scudiero, R.; Rosati, L. Glyphosate Exposure Induces Cytotoxicity, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Activation of ERα and ERβ Estrogen Receptors in Human Prostate PNT1A Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milesi, M.M.; Lorenz, V.; Durando, M.; Rossetti, M.F.; Varayoud, J. Glyphosate Herbicide: Reproductive Outcomes and Multigenerational Effects. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 672532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, H.M.; Bariami, H.; Park, H.L. Potential Role of Glyphosate, Glyphosate-Based Herbicides, and AMPA in Breast Cancer Development: A Review of Human and Human Cell-Based Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesnage, R.; Phedonos, A.; Biserni, M.; Arno, M.; Balu, S.; Corton, J.C.; Ugarte, R.; Antoniou, M.N. Evaluation of Estrogen Receptor Alpha Activation by Glyphosate-Based Herbicide Constituents. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. Comprehensive Risk-Benefit Assessment of Chemicals: A Case Study on Glyphosate. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 13, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makame, K.R.; Aljaber, Y.; Sherif, M.; Ádám, B.; Nagy, K. Genotoxic Activity of Glyphosate and Co-Formulants in Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Assessed by the Micronucleus Test in Human Mononuclear White Blood Cells. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprakaisang, S.; Thiantanawat, A.; Rangkadilok, N.; Suriyo, T.; Satayavivad, J. Glyphosate Induces Human Breast Cancer Cells Growth via Estrogen Receptors. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritana, N.; Suriyo, T.; Kanitwithayanun, J.; Songvasin, B.H.; Thiantanawat, A.; Satayavivad, J. Glyphosate Induces Growth of Estrogen Receptor Alpha Positive Cholangiocarcinoma Cells via Non-Genomic Estrogen Receptor/ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.P.; Araya-Osorio, R.; Mera-Adasme, R.; Calaf, G.M. Glyphosate Mimics 17β-Estradiol Effects Promoting Estrogen Receptor Alpha Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manservisi, F.; Lesseur, C.; Panzacchi, S.; Mandrioli, D.; Falcioni, L.; Bua, L.; Manservigi, M.; Spinaci, M.; Galeati, G.; Mantovani, A.; et al. The Ramazzini Institute 13-Week Pilot Study Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Administered at Human-Equivalent Dose to Sprague Dawley Rats: Effects on Development and Endocrine System. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A Framework for Formulating Good Questions to Explore the Association of Environmental and Other Exposures with Health Outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in The Lancet: Formatting Guidelines. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/pb-assets/Lancet/authors/metaguidelines-1753449032577.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Patino, C.M.; Ferreira, J.C. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Studies: Definitions and Why They Matter. J. Bras. De Pneumol. 2018, 44, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Pinnock, H.; Epiphaniou, E.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.L.; Schwappach, A.; Purushotham, N.; Jacob, S.; Griffiths, C.J.; Greenhalgh, T.; et al. Exclusion Criteria for Meta-Reviews. 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK263852/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Jap, J.; Saldanha, I.J.; Smith, B.T.; Lau, J.; Schmid, C.H.; Li, T. Features and Functioning of Data Abstraction Assistant, a Software Application for Data Abstraction during Systematic Reviews. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, M.; Stryhn, H.; Sanchez, J. Data Extraction and Comparison for Complex Systematic Reviews: A Step-by-Step Guideline and an Implementation Example Using Open-Source Software. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rosario Crespo Garrido, I.; Loureiro García, M.; Gutleber, J.; Crespo Garrido, I.R.; Loureiro García, M.; Gutleber, J. The Value of an Open Scientific Data and Documentation Platform in a Global Project: The Case of Zenodo. In The Economics of Big Science 2.0; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrye, T.; Mbada, C.; Hakimi, Z.; Fatoye, F. Validation of the Quality Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Real-World Studies. J. Evid. Based Med. 2025, 18, e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardener, P.; Lawton, R. Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS): An Appraisal Tool for Methodological and Reporting Quality in Systematic Reviews of Mixed- or Multi-Method Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Introduction to the GRADE Tool for Rating Certainty in Evidence and Recommendations. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panis, C.; de Paula Filho, A.R.P.; Smith, S.F.; Oviedo, J.; Amarante, M.K.; Concato, V.; Pavanelli, W.R.; Estevam, M.; Rabelo, R.S.; da Costa, O.M.M.M.; et al. Genome-Wide Gene Expression Changes in Breast Cancer Cells Following Very Low-Dose Exposure to Pesticides (Glyphosate and Atrazine) at Drinking Water Levels. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 119, 104802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Tait, S.; Fabbrizi, E.; Perugini, M.; Rocca, C. La Comparison of the Toxicological Effects of Pesticides in Non-Tumorigenic MCF-12A and Tumorigenic MCF-7 Human Breast Cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves Rebello Alves, L.; Merigueti, L.P.; Casotti, M.C.; Cancian de Araújo, B.; Silva dos Reis Trabach, R.; do Carmo Pimentel Batitucci, M.; Meira, D.D.; de Paula, F.; de Vargas Wolfgramm dos Santos, E.; Louro, I.D. Glyphosate-Based Herbicide as a Potential Risk Factor for Breast Cancer. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 200, 115404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stur, E.; Aristizabal-Pachon, A.F.; Peronni, K.C.; Agostini, L.P.; Waigel, S.; Chariker, J.; Miller, D.M.; Thomas, S.D.; Rezzoug, F.; Detogni, R.S.; et al. Glyphosate-Based Herbicides at Low Doses Affect Canonical Pathways in Estrogen Positive and Negative Breast Cancer Cell Lines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A.; Boscolo, A.; Zarantonello, F.; Pettenuzzo, T.; Sella, N.; Geraldini, F.; Munari, M.; Navalesi, P. Enhancing Study Quality Assessment: An in-Depth Review of Risk of Bias Tools for Meta-Analysis—A Comprehensive Guide for Anesthesiologists. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2023, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, T.E.; Lin, Z.; Mery, L.S. An Exploratory Analysis of the Effect of Pesticide Exposure on the Risk of Spontaneous Abortion in an Ontario Farm Population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, M.N.; Nicolas, A.; Mesnage, R.; Biserni, M.; Rao, F.V.; Martin, C.V. Glyphosate Does Not Substitute for Glycine in Proteins of Actively Dividing Mammalian Cells. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Diwan, M.; Lahimer, M.; Bach, V.; Gosselet, F.; Khorsi-Cauet, H.; Candela, P. Impact of Pesticide Residues on the Gut-Microbiota–Blood–Brain Barrier Axis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmanninger, A.; Brandmaier, V.; Spangl, B.; Gruber, E.; Takács, E.; Mörtl, M.; Klátyik, S.; Székács, A.; Zaller, J.G. Glyphosate-Based Herbicide Formulations and Their Relevant Active Ingredients Affect Soil Springtails Even Five Months after Application. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquavella, J. Epidemiologic Studies of Glyphosate and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Review with Consideration of Exposure Frequency, Systemic Dose, and Study Quality. Glob. Epidemiol. 2023, 5, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annett, R.; Habibi, H.R.; Hontela, A. Impact of Glyphosate and Glyphosate-Based Herbicides on the Freshwater Environment. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.S.; Mollari, M.; Tassinari, V.; Alimonti, C.; Ubaldi, A.; Cuva, C.; Marcoccia, D. Overview of Human Health Effects Related to Glyphosate Exposure. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1474792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopko, B.; Tejral, G.; Bitti, G.; Abate, M.; Medvedikova, M.; Hajduch, M.; Chloupek, J.; Fajmonova, J.; Skoric, M.; Amler, E.; et al. Glyphosate Interaction with EEF1α1 Indicates Altered Protein Synthesis: Evidence for Reduced Spermatogenesis and Cytostatic Effect. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 14848–14857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.P.K.; Sethi, N.; Mohan, A.; Datta, S.; Girdhar, M. Glyphosate Toxicity for Animals. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuselier, S.G.; Ireland, D.; Fu, N.; Rabeler, C.; Collins, E.M.S. Comparative Toxicity Assessment of Glyphosate and Two Commercial Formulations in the Planarian Dugesia Japonica. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1200881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Moya, C.; Silva, M.R.; Valdez Ramírez, C.; Gallardo, D.G.; León Sánchez, R.; Aguirre, A.C.; Velasco, A.F. Comparison of the in vivo and in vitro Genotoxicity of Glyphosate Isopropylamine Salt in Three Different Organisms. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2014, 37, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evalen, P.S.; Barnhardt, E.N.; Ryu, J.; Stahlschmidt, Z.R. Toxicity of Glyphosate to Animals: A Meta-Analytical Approach. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palberg, D.; Kaszecki, E.; Dhanjal, C.; Kisiała, A.; Morrison, E.N.; Stock, N.; Emery, R.J.N. Impact of Glyphosate and Glyphosate-Based Herbicides on Phyllospheric Methylobacterium. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klátyik, S.; Simon, G.; Takács, E.; Oláh, M.; Zaller, J.G.; Antoniou, M.N.; Benbrook, C.; Mesnage, R.; Székács, A. Toxicological Concerns Regarding Glyphosate, Its Formulations, and Co-Formulants as Environmental Pollutants: A Review of Published Studies from 2010 to 2025. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Liu, X.Q. Modeling Development of Breast Cancer: From Tumor Microenvironment to Preclinical Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1466017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housden, B.E.; Muhar, M.; Gemberling, M.; Gersbach, C.A.; Stainier, D.Y.R.; Seydoux, G.; Mohr, S.E.; Zuber, J.; Perrimon, N. Loss-of-Function Genetic Tools for Animal Models: Cross-Species and Cross-Platform Differences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 18, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Why Animal Model Studies Are Lost in Translation. J. Cardiovasc. Aging 2022, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, J.V.; Court-Marques, D.; Tiramani, M.; Reich, H.; Pfeil, R.; Istace, F.; Crivellente, F. Glyphosate Toxicity and Carcinogenicity: A Review of the Scientific Basis of the European Union Assessment and Its Differences with IARC. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2723–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraeyman, N. Glyphosate 2023–2033; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoren, M.J.; Schiestl, R.H. Glyphosate-Based Herbicides and Cancer Risk: A Post-IARC Decision Review of Potential Mechanisms, Policy and Avenues of Research. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klátyik, S.; Simon, G.; Oláh, M.; Mesnage, R.; Antoniou, M.N.; Zaller, J.G.; Székács, A. Terrestrial Ecotoxicity of Glyphosate, Its Formulations, and Co-Formulants: Evidence from 2010–2023. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, A.; Coggins, M.A.; Koch, H.M. Human Biomonitoring of Glyphosate Exposures: State-of-the-Art and Future Research Challenges. Toxics 2020, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, S.R.; Alves, M.G.; Oliveira, P.F.; Zamoner, A. Critical Review of Glyphosate-Induced Oxidative and Hormonal Testicular Disruption. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Tovar-Sánchez, E.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; Rosas-Ramírez, M.E.; Rodríguez, A.; Mussali-Galante, P. Glyphosate Pollution Treatment and Microbial Degradation Alternatives, a Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnajafi, K.; Iqbal, M.A. Mass-Spectrometry Based Metabolomics: An Overview of Workflows, Strategies, Data Analysis and Applications. Proteome Sci. 2025, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defarge, N.; Spiroux de Vendômois, J.; Séralini, G.E. Toxicity of Formulants and Heavy Metals in Glyphosate-Based Herbicides and Other Pesticides. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, H.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, W.; Tao, L. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Effects of Glyphosate Herbicides in Human Liver, Lung, and Nerve. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2019, 54, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defarge, N.; Takács, E.; Lozano, V.L.; Mesnage, R.; de Vendômois, J.S.; Séralini, G.E.; Székács, A. Co-Formulants in Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Disrupt Aromatase Activity in Human Cells below Toxic Levels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophides, T.; Karekla, M. Revisiting Ecological Fallacy: Are Single-Case Experimental Study Designs Even More Relevant in the Era of Precision Medicine? Precis. Clin. Med. 2024, 7, pbae025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, J.A.; Brueggemeier, R.W. Estrogen Receptor-Mediated Regulation of Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Breast Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Deng, Z. Oxidative Stress: Signaling Pathways, Biological Functions, and Disease. MedComm (Beijing) 2025, 6, e70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ming, H.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Huang, C. Redox Regulation: Mechanisms, Biology and Therapeutic Targets in Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Type of Study | Experimental Model | Glyphosate Concentration | Aim of the Study | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | in vitro | Human breast cell lines: MCF-7 (ER+ tumorigenic) and MCF-12A (non-tumorigenic) | 50–500 ppb | Evaluate the toxicological effects of glyphosate (and other pesticides) at environmentally relevant concentrations on a cancerous vs. a non-cancerous breast cell line, assessing multiple cellular endpoints | Glyphosate reduced viability, ATP levels, and ROS in breast cells, triggered apoptosis, and showed endocrine-disrupting effects by altering hormone receptor expression and estradiol secretion [34]. |

| 2a | in vitro | Human breast cancer cells (MCF-7, T47D, MDA-MB-231) | 1 × 10−8–1 × 10−3 M | Evaluate estrogenic effects in ER+ and ER– cells | Glyphosate induces weak ERα-mediated proliferation and gene expression [21] |

| 3a | in vitro | T47D-KBluc, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | 10−12–10−6 M | Assess ER-mediated transcription and proliferation | Glyphosate acts as weak ER agonist; GBHs less effective [16] |

| 4a | in vitro | T47D, T47D-KBluc, MDA-MB-231 | 10−12–10−6 M | Investigate ER-mediated effects and interaction with genistein | Low-dose glyphosate shows estrogenic effects; genistein enhances them [19] |

| 5a | in vitro | MCF-7 (tumorigenic) and MCF-12A (non-tumorigenic) | 230 pM–2.3 µM | Compare toxicological effects of pesticides at child-relevant concentrations | Glyphosate alters energy metabolism and shows endocrine-disrupting effects in both models [35] |

| 6b | in vitro | Non-tumorigenic human breast epithelial cells (MCF10A) and tumorigenic breast cancer cells (MCF7, ER+; MDA-MB-231, ER−) | GBHs at 0.000001–1% (v/v) (≈0.0048 µg/mL to 4.8 mg/mL glyphosate; ~0.03 µM–28 mM) | Verify the impact of a glyphosate-based herbicide on non-tumor and tumor breast cells by analyzing breast cancer gene expression and potential epigenetic changes linked to cancer risk | GBHs showed greater toxicity in non-tumor MCF10A cells than in cancer cells, reducing viability and suppressing BRCA genes. It altered DNA repair gene expression without estrogenic activity and induced complex, non-reversible epigenetic effects [36]. |

| 7b | in vitro | MCF-7 (ER+) and MDA-MB-468 (ER–) | 0.01–0.30% v/v (≈1.1 mM) | Identify gene expression and pathway changes after short-term exposure | Low-dose GBHs and AMPA affect cell cycle and DNA repair independently of ER status [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alcalá-Pérez, M.A.; Hernández-Fuentes, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Diaz-Llerenas, U.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Guzmán-Esquivel, J.; Rojas-Larios, F.; Ramos-Organillo, Á.A.; Pineda-Urbina, K.; Flores-Álvarez, J.M.; et al. Glyphosate as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant and Its Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Evidence. Toxics 2026, 14, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010026

Alcalá-Pérez MA, Hernández-Fuentes GA, Garza-Veloz I, Diaz-Llerenas U, Martinez-Fierro ML, Guzmán-Esquivel J, Rojas-Larios F, Ramos-Organillo ÁA, Pineda-Urbina K, Flores-Álvarez JM, et al. Glyphosate as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant and Its Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Evidence. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlcalá-Pérez, Mario A., Gustavo A. Hernández-Fuentes, Idalia Garza-Veloz, Uriel Diaz-Llerenas, Margarita L. Martinez-Fierro, José Guzmán-Esquivel, Fabian Rojas-Larios, Ángel A. Ramos-Organillo, Kayim Pineda-Urbina, José M. Flores-Álvarez, and et al. 2026. "Glyphosate as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant and Its Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Evidence" Toxics 14, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010026

APA StyleAlcalá-Pérez, M. A., Hernández-Fuentes, G. A., Garza-Veloz, I., Diaz-Llerenas, U., Martinez-Fierro, M. L., Guzmán-Esquivel, J., Rojas-Larios, F., Ramos-Organillo, Á. A., Pineda-Urbina, K., Flores-Álvarez, J. M., Mojica-Sánchez, J. P., Cárdenas-Magaña, J. A., Villa-Martínez, C. A., & Delgado-Enciso, I. (2026). Glyphosate as an Emerging Environmental Pollutant and Its Effects on Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Evidence. Toxics, 14(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010026