Seasonal Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions of PM2.5 in a County-Level City of Jing–Jin–Ji Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

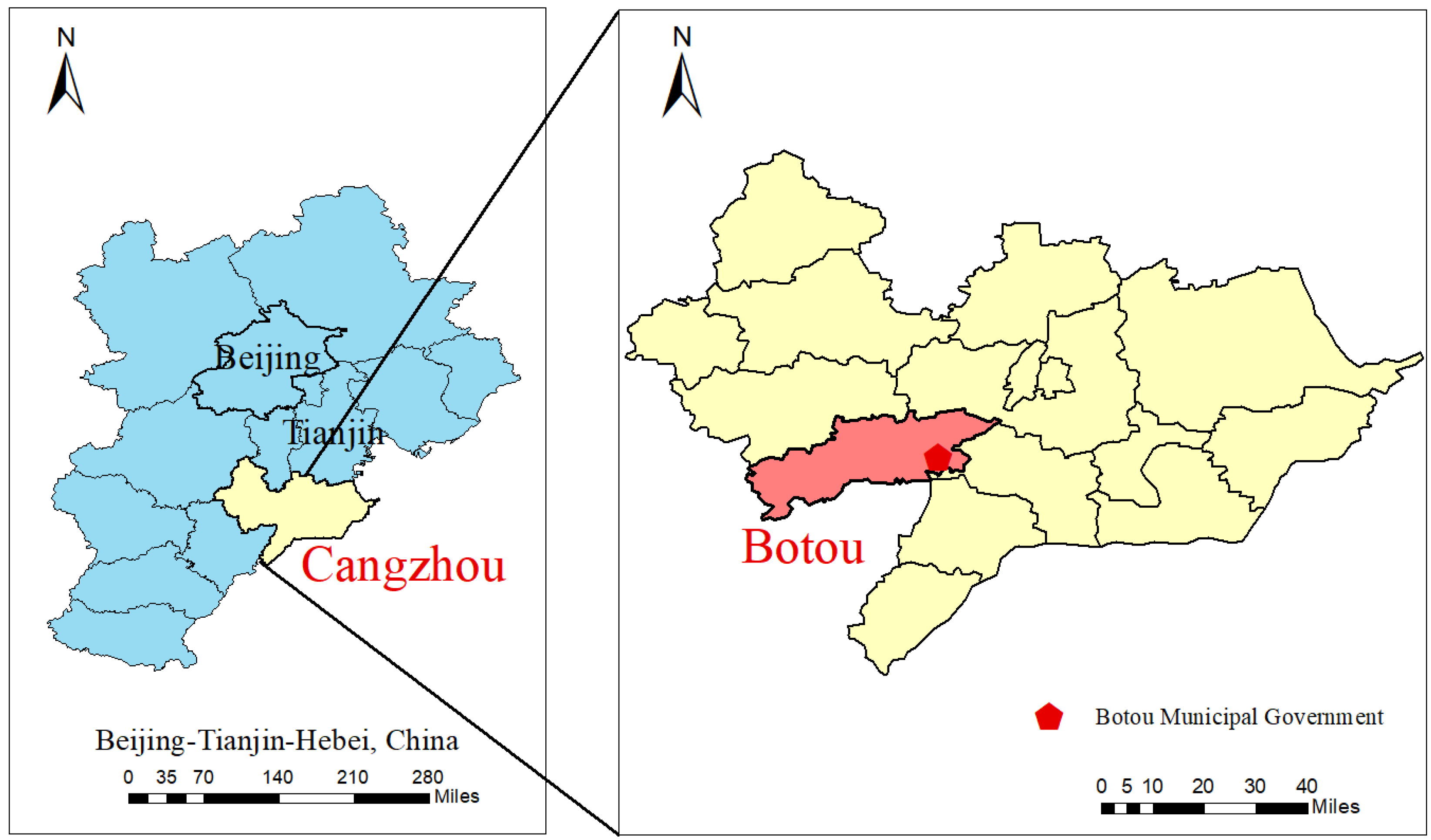

2.1. Research Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Sample Analysis

2.3. Sources of Gaseous Pollutants and Meteorological Data

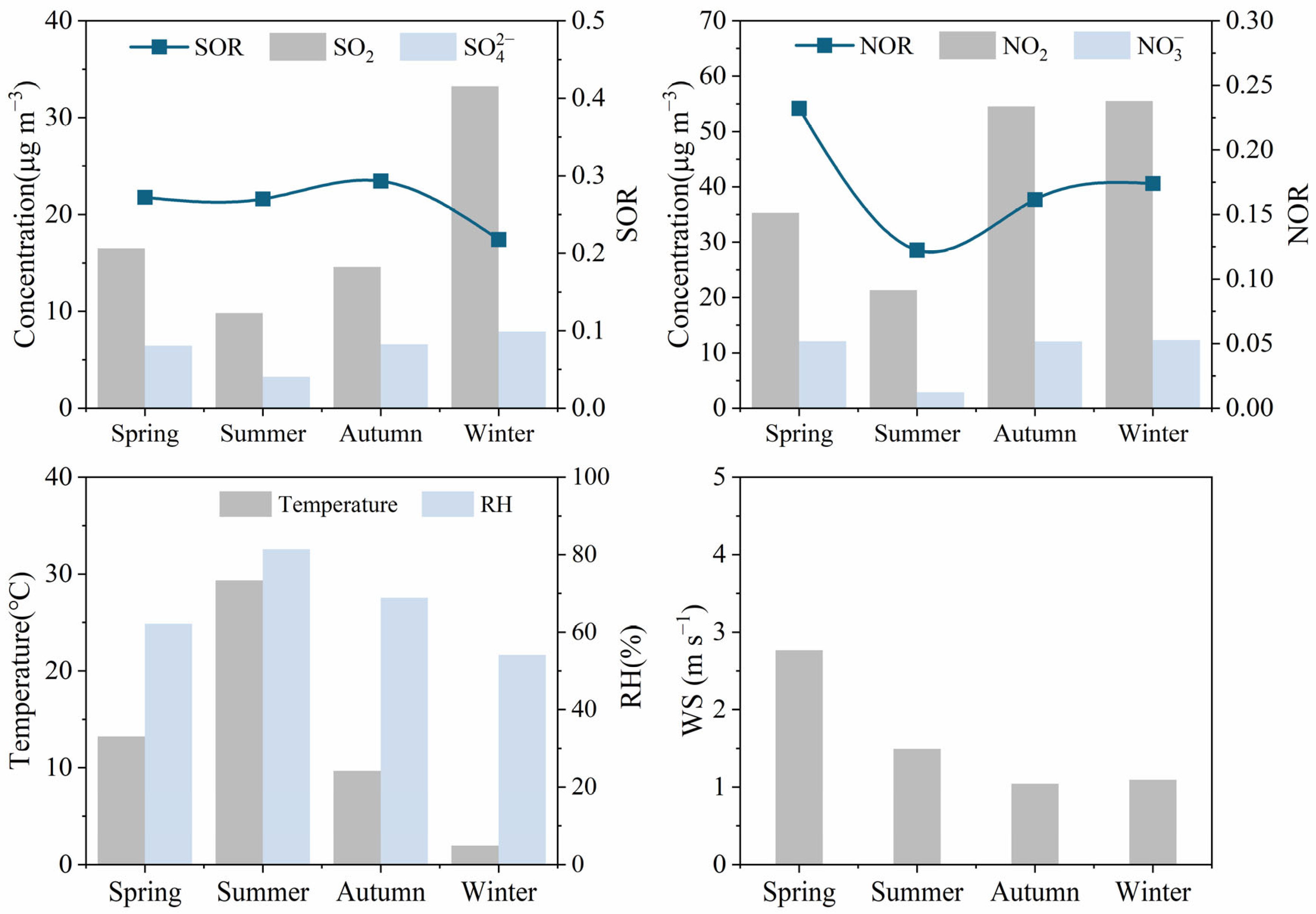

2.4. Sulfur Oxidation Ratio (SOR) and Nitrogen Oxidation Ratio (NOR)

2.5. Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF)

3. Results and Discussion

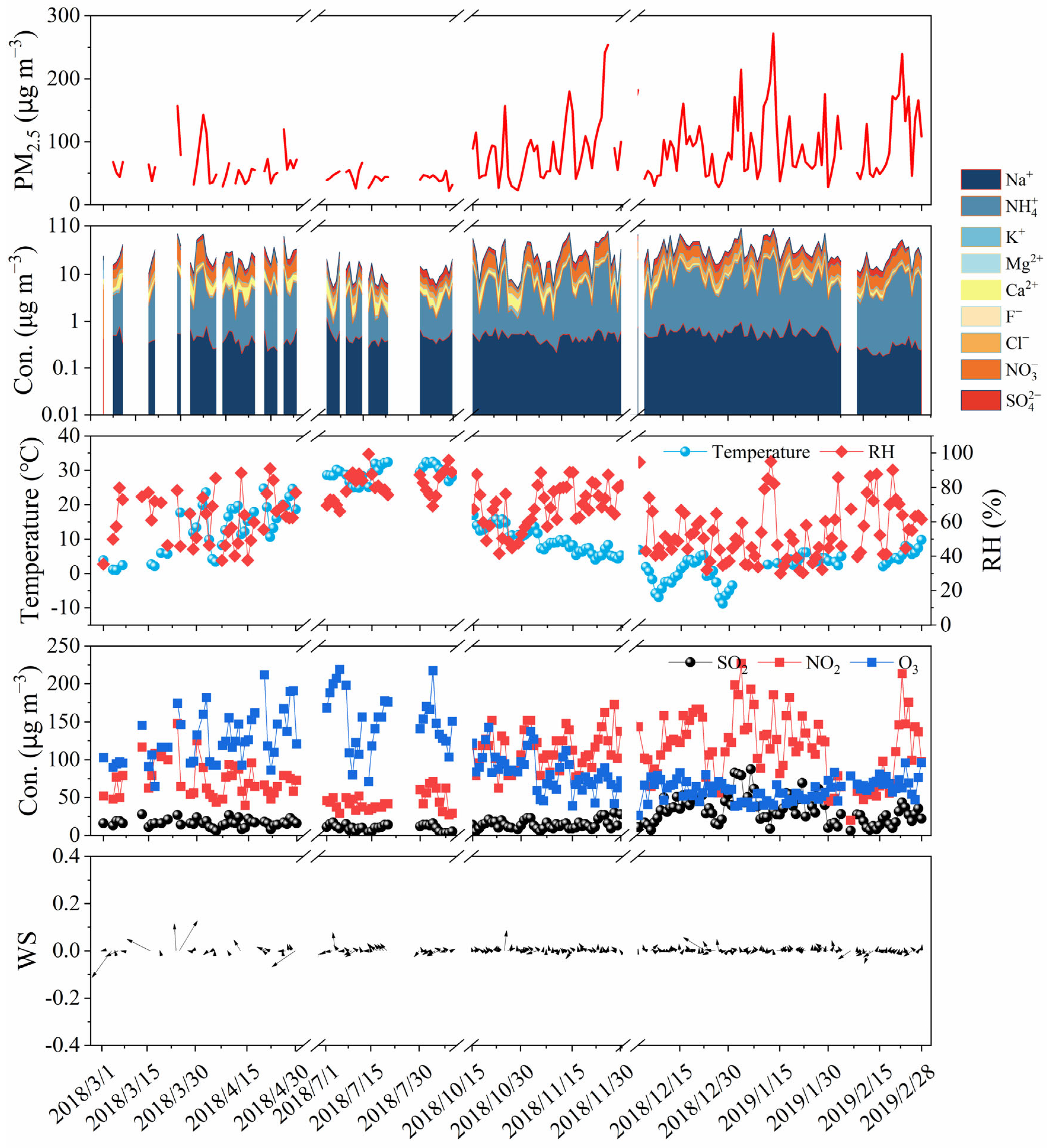

3.1. Seasonal Variation of PM2.5 Mass Concentration

3.2. Seasonal Variation of WSIIs

3.3. Existing Formation of SIA

3.4. Analysis of WSIIs Sources

3.4.1. NO3−/SO42− Ratio

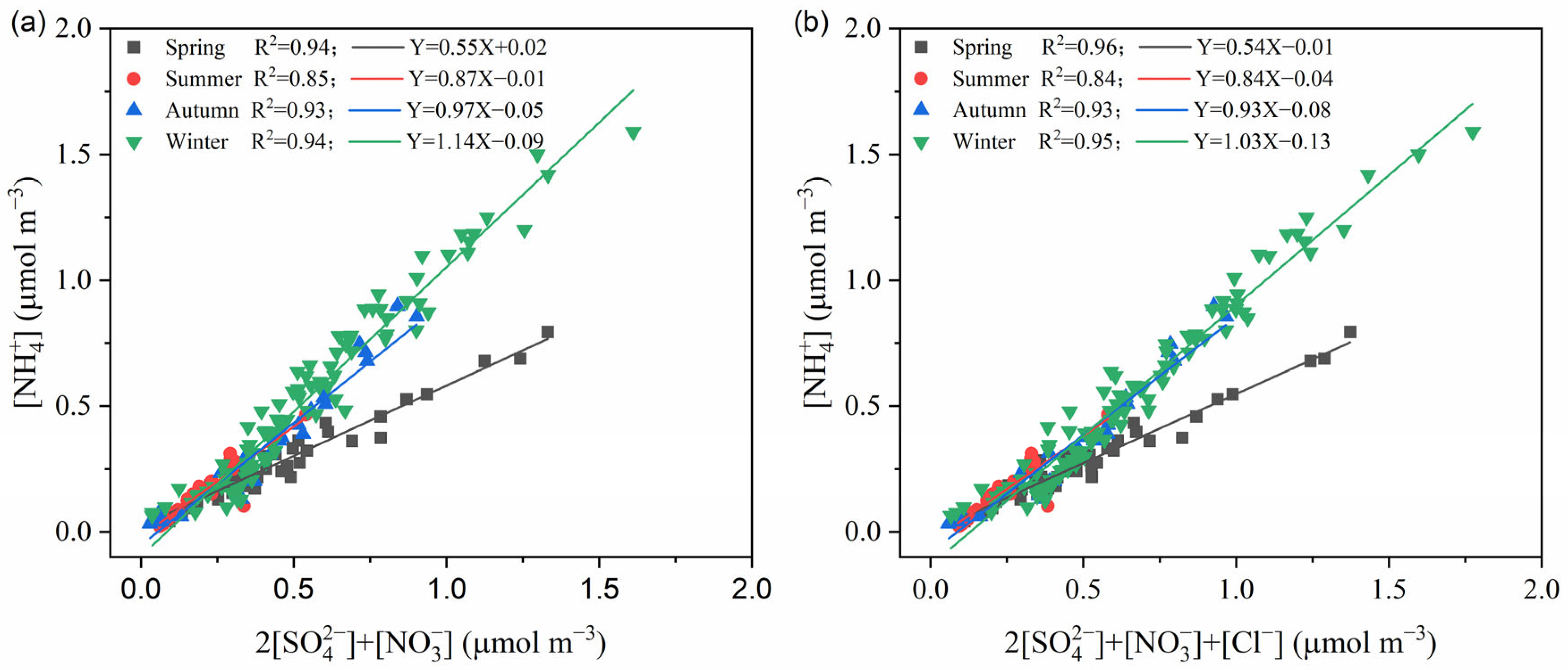

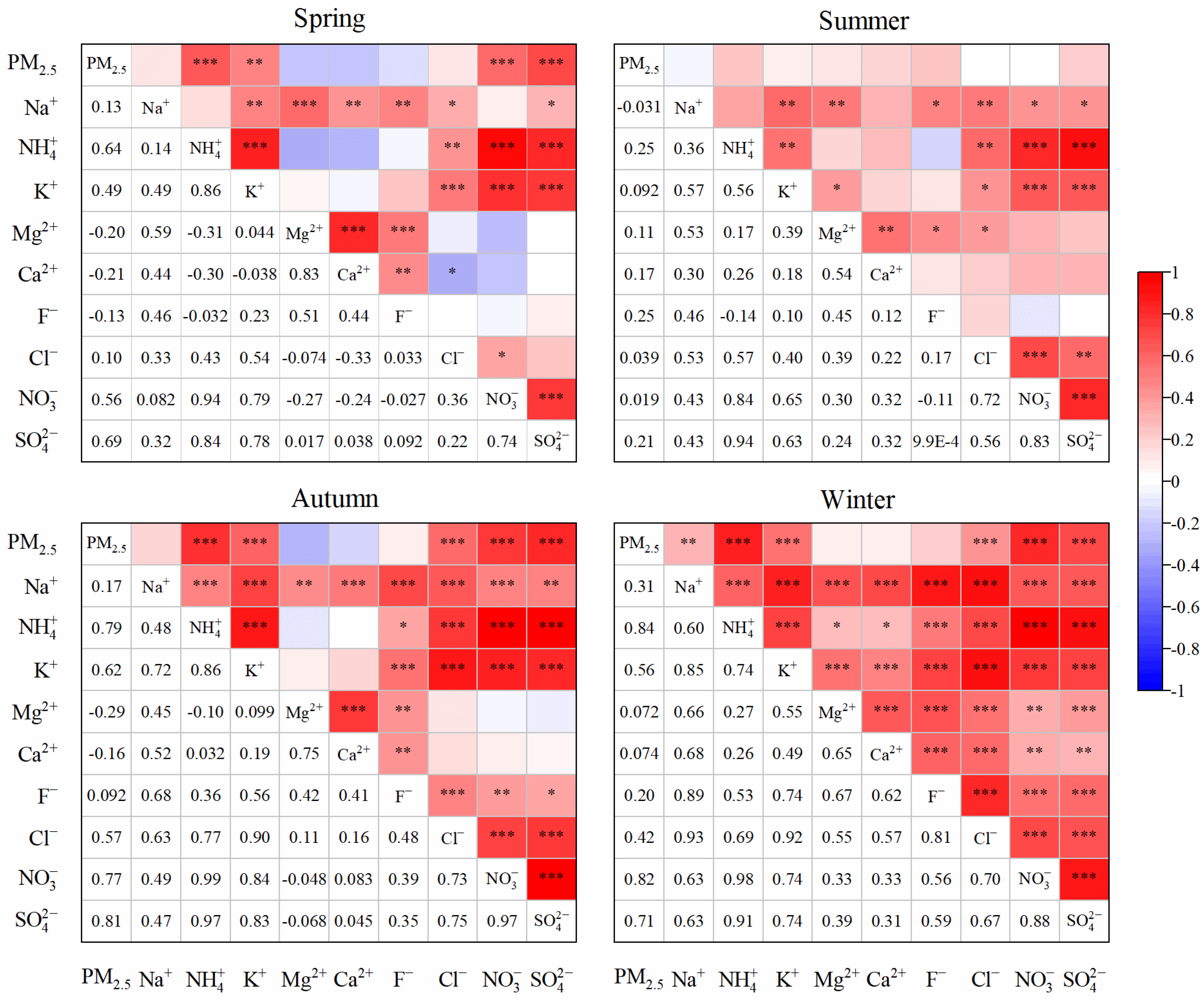

3.4.2. Ion Correlation Analysis

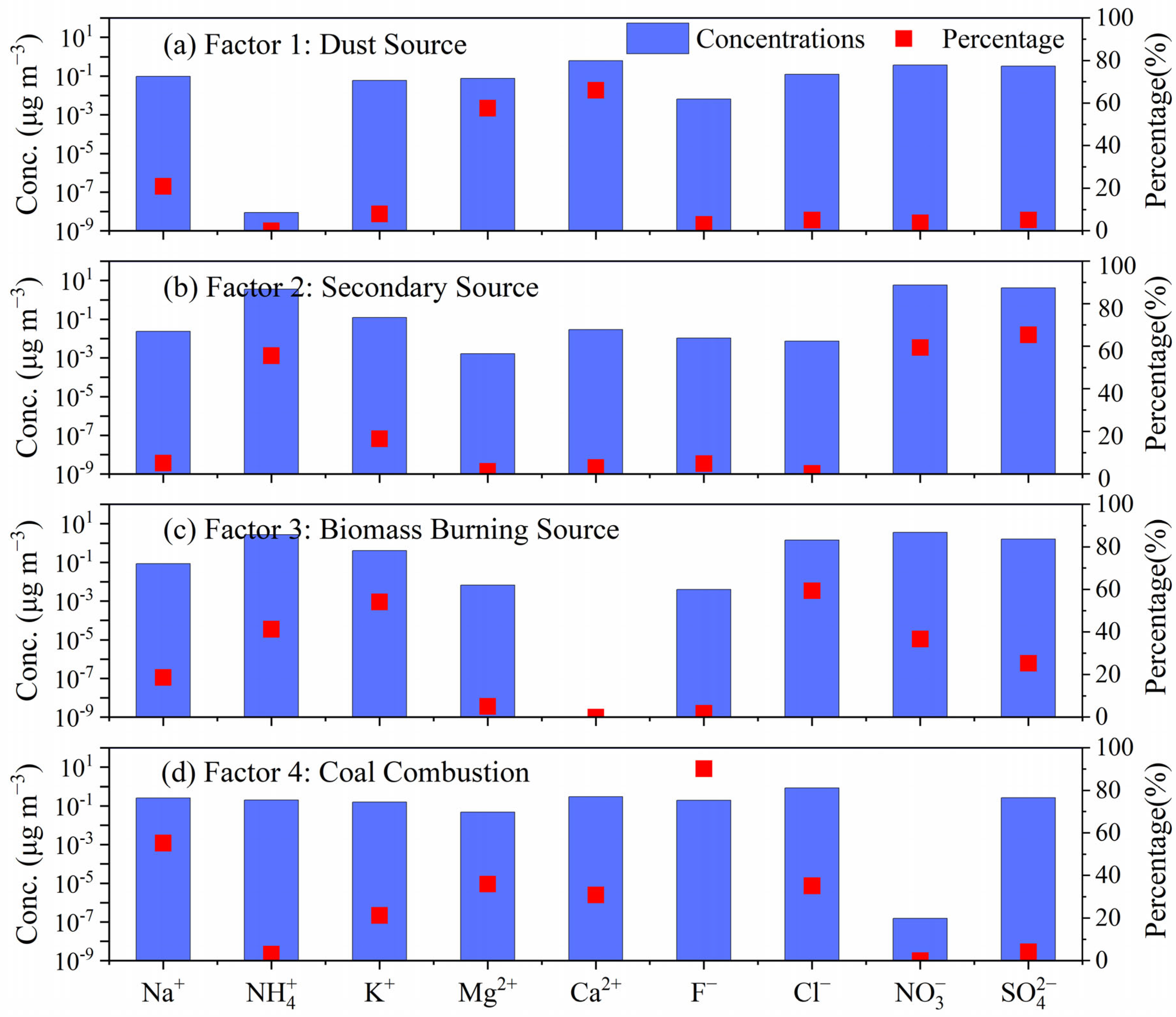

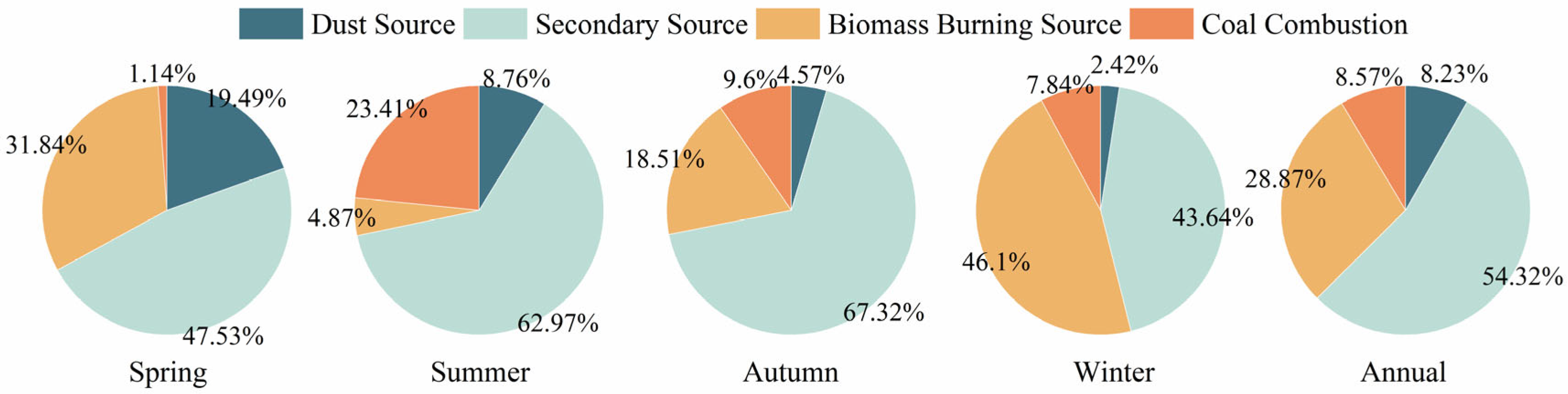

3.4.3. PMF Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WSIIs | water-soluble inorganic ions |

| PMF | Positive Matrix Factorization |

| BTH | Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei |

| SOR | Sulfur Oxidation Ratio |

| NOR | Nitrogen Oxidation Ratio |

| SIA | secondary inorganic aerosols |

References

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. 2022 China Ecological and Environmental Status Bulletin; Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- He, Q.; Yan, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Characterization and source analysis of water-soluble inorganic ionic species in PM2.5 in Taiyuan city, China. Atmos. Res. 2017, 184, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Hu, B.; Wen, T.; Xin, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Size-resolved aerosol water-soluble ions during the summer and winter seasons in Beijing: Formation mechanisms of secondary inorganic aerosols. Chemosphere 2017, 183, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carslaw, K.S.; Lee, L.A.; Reddington, C.L.; Pringle, K.J.; Rap, A.; Forster, P.M.; Mann, G.W.; Spracklen, D.V.; Woodhouse, M.T.; Regayre, L.A. Large contribution of natural aerosols to uncertainty in indirect forcing. Nature 2013, 503, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.S.; Dong, F.; He, D.; Zhao, X.J.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, W.Z.; Yao, Q.; Liu, H.Y. Characteristics of concentrations and chemical compositions for PM2.5 in the region of Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 4631–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Gao, E.; An, J.; Xu, Y. Different variations in PM2.5 sources and their specific health risks in different periods in a heavily polluted area of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. Atmos. Res. 2024, 308, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, I.; Ren, L.; Li, G.; Zhou, T.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Kim, T.; Cheong, Y.; Kim, S.; Chae, H.; et al. Effects of seasonal management programs on PM2.5 in Seoul and Beijing using DN-PMF: Collaborative efforts from the Korea-China joint research. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansuebsri, S.; Kraisitnitikul, P.; Wiriya, W.; Chantara, S. Fresh and aged PM2.5 and their ion composition in rural and urban atmospheres of Northern Thailand in relation to source identification. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wen, T.; Ji, D.; Wang, Y. Seasonal variation and secondary formation of size-segregated aerosol water-soluble inorganic ions during pollution episodes in Beijing. Atmos. Res. 2016, 168, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hao, Z.; Chen, Q. On the characteristics of solar radiative transfer and participating media in Harbin, China. J. Photonics Energy 2019, 10, 023504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yang, Z.; Tui, Y.; Wang, J. Fine particulate matter pollution characteristics and source apportionment of Changchun atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 12694–12705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, H.; Tong, L. The Interrelated Pollution Characteristics of Atmospheric Speciated Mercury and Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions in Ningbo, China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Xu, R.; Gao, C.X.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, K.; Yu, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Socioeconomic disparity in the association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality in 2640 Chinese counties. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, M.; Han, Q.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, A.; Mao, P.; Xiong, Q.; et al. Health risk assessment of PM2.5 heavy metals in county units of northern China based on Monte Carlo simulation and APCS-MLR. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843, 156777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Q.; Wu, G.; Gautam, A.; Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, W.; Guan, H. Spatio-Temporal Variation Characteristics of PM2.5 in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, China, from 2013 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Yu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Di, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, W. Size-resolved aerosol water-soluble ions at a regional background station of Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei, North China. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 55, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, Z.; Wang, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, M.; Cheng, Y.; Han, J.; Jin, T. Comparison of PM2.5 components and secondary formation during the heavily polluted period of two megacities in China. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; Peng, J.; Wu, L.; Mao, H. Characteristics, sources, and health risks of inorganic elements in PM2.5 and PM10 at Tianjin Binhai international airport. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 332, 121988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hui, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Chemical characteristics of size-fractioned particles at a suburban site in Shijiazhuang, North China: Implication of secondary particle formation. Atmos. Res. 2021, 259, 105680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.; Gao, J.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chai, F. The impact of fireworks control on air quality in four Northern Chinese cities during the Spring Festival. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 800-2016; Ambient Air-Determination of the Water Soluble Cations (Li+, Na+, NH4+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) from Atmospheric Particles Ion Chromatography. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- HJ 799-2016; Ambient Air-Determination of the Water Soluble Anions (F−, Cl−, Br−, NO2−, NO3−, PO43−, SO32−, SO42−) from Atmospheric Particles-Ion Chromatography. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Pierson, W.R.; Brachaczek, W.W.; Mckee, D.E. Sulfate Emissions from Catalyst-Equipped Automobiles on the Highway. J. Air Pollut. Control. Assoc. 1979, 29, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K.; Dai, Q.; Li, L.; Feng, Y. Global review of recent source apportionments for airborne particulate matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3095-2012; Ambient Air Quality Standards. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Luo, L.; Bai, X.; Liu, S.; Wu, B.; Liu, W.; Lv, Y.; Guo, Z.; Lin, S.; Zhao, S.; Hao, Y. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5/PM1.0) in Beijing, China: Variations and chemical compositions as well as sources. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 121, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Cheng, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, S. PM2.5 Chemical Composition Analysis in Different Functional Subdivisions in Tangshan, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wen, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, N.; Fang, X.; Xiao, H. Characteristics of chemical composition and seasonal variations of PM2.5 in Shijiazhuang, China: Impact of primary emissions and secondary formation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 677, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, W.R.; Watson, J.G.; Robinson, N.F.; Steiner, W.; Sylte, W.W. The ammonium nitrate particle equivalent of NOX emissions for wintertime conditions in Central California’s San Joaquin Valley. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 4711–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Yin, S. Elevated particle acidity enhanced the sulfate formation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Zhengzhou, China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 296, 118716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Cai, T.; Fang, D.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y. Concentrations and chemical compositions of fine particles (PM2.5) during haze and non-haze days in Beijing. Atmos. Res. 2016, 174–175, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhu, C.; Hao, J.; Liu, H.; Hua, S.; Tian, H. Temporal-spatial characteristics and source apportionment of PM2.5 as well as its associated chemical species in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Chen, D.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, H. Policy-driven variations in oxidation potential and source apportionment of PM2.5 in Wuhan, central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, G.D.; Ito, K.; Lall, R. A source apportionment of U.S. fine particulate matter air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 3924–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Lu, H.; Yi, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, N.; Fang, X.; Xiao, H. Characterization and source analysis of water–soluble ions in PM2.5 at a background site in Central China. Atmos. Res. 2020, 239, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.-l.; Shi, C.-e.; Wu, B.-w.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Yu, C. Characteristics of the water-soluble components of aerosol particles in Hefei, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 42, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.C.; Wang, L.T.; Zhang, F.F.; Wei, Z.; Ma, S.M.; Ma, X.; Yang, J. Characteristics of concentrations and water-soluble inorganic ions in PM2.5 in Handan City, Hebei province, China. Atmos. Res. 2016, 171, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; McPherson Donahue, N.; Tang, R.; Dong, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Han, Y. The seasonal variation, characteristics and secondary generation of PM2.5 in Xi’an, China, especially during pollution events. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ren, J. Seasonal characteristics of PM2.5 and its chemical species in the northern rural China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Talifu, D.; Gao, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Abulizi, A.; Wang, X.; Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Temporal Distribution and Source Apportionment of Composition of Ambient PM2.5 in Urumqi, North-West China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Shi, M.; Liu, W.; Mao, Y.; Hu, J.; Tian, Q.; Chen, Z.; Hu, T.; Xing, X.; Qi, S. Characteristics and source apportionment of water-soluble inorganic ions in PM2.5 during a wintertime haze event in Huanggang, central China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdős, G.; Balogh, A. Statistical properties of mirror mode structures observed by Ulysses in the magnetosheath of Jupiter. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1996, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Chan, C.K.; Fang, M.; Cadle, S.; Chan, T.; Mulawa, P.; He, K.; Ye, B. The water-soluble ionic composition of PM2.5 in Shanghai and Beijing, China. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 4223–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, G.; Liu, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Deng, L.; Yu, J.; Peng, C. Seasonal characteristics, formation mechanisms and source origins of PM2.5 in two megacities in Sichuan Basin, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiol, M.; Hopke, P.K.; Felton, H.D.; Frank, B.P.; Rattigan, O.V.; Wurth, M.J.; LaDuke, G.H. Analysis of major air pollutants and submicron particles in New York City and Long Island. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 148, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zong, Z.; Tian, C.; Li, J.; Sun, R.; Ma, W.; Li, T.; Zhang, G. Reapportioning the sources of secondary components of PM2.5: A combined application of positive matrix factorization and isotopic evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xing, Z.; Deng, J.; Du, K. Characterizing and sourcing ambient PM2.5 over key emission regions in China I: Water-soluble ions and carbonaceous fractions. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 135, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, J.; Qu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Yao, R.; Cao, J. Characteristics and Source Analysis of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions in PM10 in a Typical Mining City, Central China. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Hu, B.; Wen, T.; Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, F.; Ji, D.; Wang, L. Chemical characterization and source identification of PM2.5 at multiple sites in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 12941–12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, S.; Cheng, K.; Yin, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W. Seasonal variation, formation mechanisms and potential sources of PM2.5 in two typical cities in the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, J.; Ohara, T. Long-term historical trends in air pollutant emissions in Asia: Regional Emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 3. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 12761–12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Song, N.; Dai, Q.; Mei, R.; Sui, B.; Bi, X.; Feng, Y. Chemical composition and source apportionment of ambient PM2.5 during the non-heating period in Taian, China. Atmos. Res. 2016, 170, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasoe, M.A.; Artaxo, P.; Miguel, A.H.; Allen, A.G. Chemical composition of aerosol particles from direct emissions of vegetation fires in the Amazon Basin: Water-soluble species and trace elements. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Mu, L.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Feng, C.; Zheng, L. Characteristics and source apportionment of water-soluble inorganic ions in atmospheric particles in Lvliang, China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 4203–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Annual | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 0.42 ± 0.14 | 0.47 ± 0.17 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.51 ± 0.21 |

| Cl− | 2.51 ± 1.79 | 1.83 ± 0.92 | 1.16 ± 0.16 | 1.91 ± 0.84 | 3.63 ± 2.13 |

| Ca2+ | 1.04 ± 0.82 | 1.85 ± 1.31 | 0.88 ± 0.63 | 1.00 ± 0.34 | 0.71 ± 0.35 |

| Mg2+ | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.04 |

| K+ | 0.78 ± 0.48 | 0.71 ± 0.32 | 0.27 ± 0.09 | 0.66 ± 0.31 | 1.05 ± 0.53 |

| NH4+ | 7.02 ± 5.69 | 5.08 ± 3.00 | 2.54 ± 1.92 | 7.36 ± 6.06 | 9.33 ± 6.11 |

| F− | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.09 |

| NO3− | 10.86 ± 8.72 | 12.08 ± 9.53 | 2.87 ± 1.88 | 12.07 ± 9.32 | 12.32 ± 7.87 |

| SO42− | 6.63 ± 4.07 | 6.46 ± 3.84 | 3.24 ± 2.04 | 6.59 ± 4.07 | 7.89 ± 4.01 |

| SIA/WSIIs (%) | 78 ± 11 | 78 ± 10 | 69 ± 11 | 78 ± 15 | 81 ± 7 |

| SIA/PM2.5 (%) | 35 ± 14 | 45 ± 15 | 25 ± 13 | 29 ± 14 | 38 ± 12 |

| WSIIs/PM2.5 (%) | 44 ± 16 | 57 ± 16 | 35 ± 15 | 35 ± 14 | 47 ± 14 |

| Sites | Sampling Time | PM2.5 | F− | Cl− | NO3− | SO42− | Na+ | NH4+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botou | 2018.3–2019.2 | 79.15 ± 48.44 | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 2.51 ± 1.79 | 10.86 ± 8.72 | 6.63 ± 4.07 | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 7.02 ± 5.69 | 0.78 ± 0.48 | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.82 |

| Hefei [36] | 2012.9–2013.8 | 86.29 | / | 1.21 | 15.14 | 15.56 | 0.48 | 7.82 | 0.96 | 0.30 | 5.24 |

| Handan [37] | 2013 | 139.4 | / | 4.4 | 20.6 | 25.2 | 0.7 | 13.0 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Handan [37] | 2014 | 116.0 | / | 4.5 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 0.6 | 14.4 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Xi’an [38] | 2018.3–2018.10 | 134.9 | 0.10 | 1.5 | 12.1 | 7.6 | 0.75 | 4.5 | 0.89 | 0.26 | 4.7 |

| Taiyuan [39] | 2017.8–2016.5 | 109.6 | / | 3.4 | 13.1 | 19.1 | 0.5 | 12.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| Urumqi [40] | 2017.9–2018.8 | 158.85 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 13.46 | 13.58 | 1.93 | 10.88 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 1.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Ren, L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Gao, S.; Ma, Q.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Y. Seasonal Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions of PM2.5 in a County-Level City of Jing–Jin–Ji Region. Toxics 2026, 14, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010017

Guo S, Ren L, Gao Y, Yang X, Li G, Gao S, Ma Q, Shen Y, Xu Y. Seasonal Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions of PM2.5 in a County-Level City of Jing–Jin–Ji Region. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Shuangyun, Lihong Ren, Yuanguan Gao, Xiaoyang Yang, Gang Li, Shuang Gao, Qingxia Ma, Yi Shen, and Yisheng Xu. 2026. "Seasonal Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions of PM2.5 in a County-Level City of Jing–Jin–Ji Region" Toxics 14, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010017

APA StyleGuo, S., Ren, L., Gao, Y., Yang, X., Li, G., Gao, S., Ma, Q., Shen, Y., & Xu, Y. (2026). Seasonal Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions of PM2.5 in a County-Level City of Jing–Jin–Ji Region. Toxics, 14(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010017