Bioaccumulation of Potential Harmful Elements in Fossorial Water Voles Inhabiting Non-Polluted Crops

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

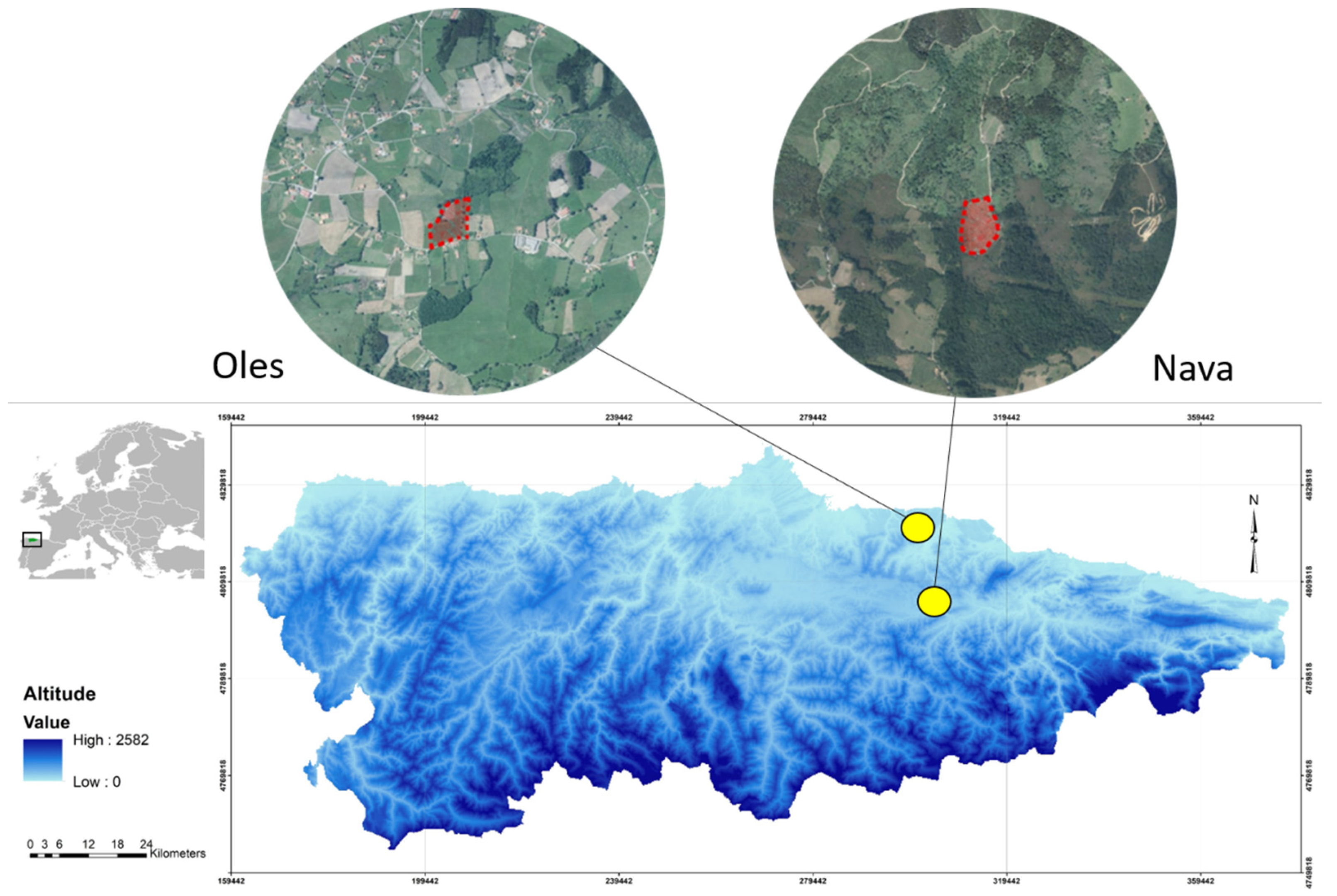

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Tissue Samples

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

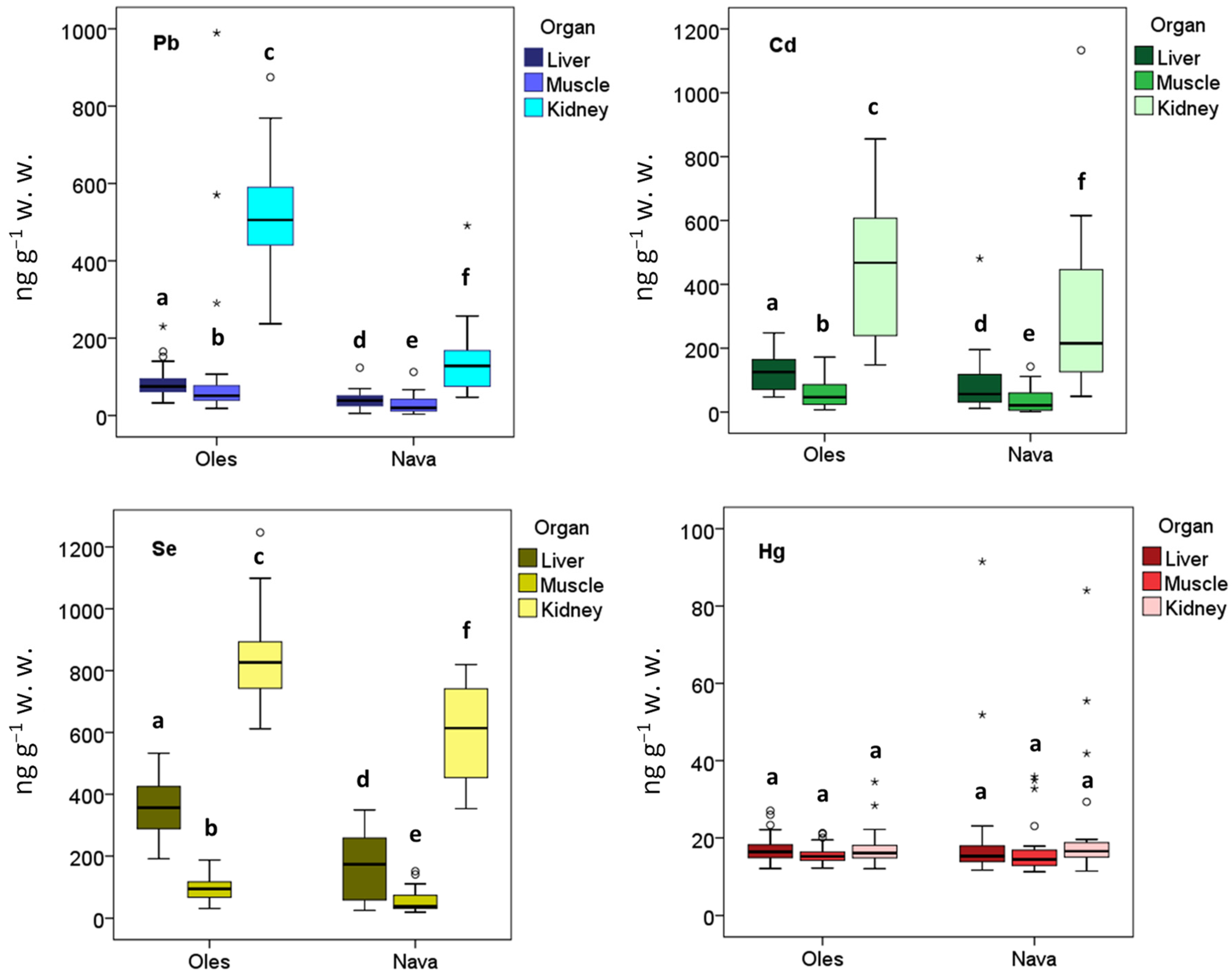

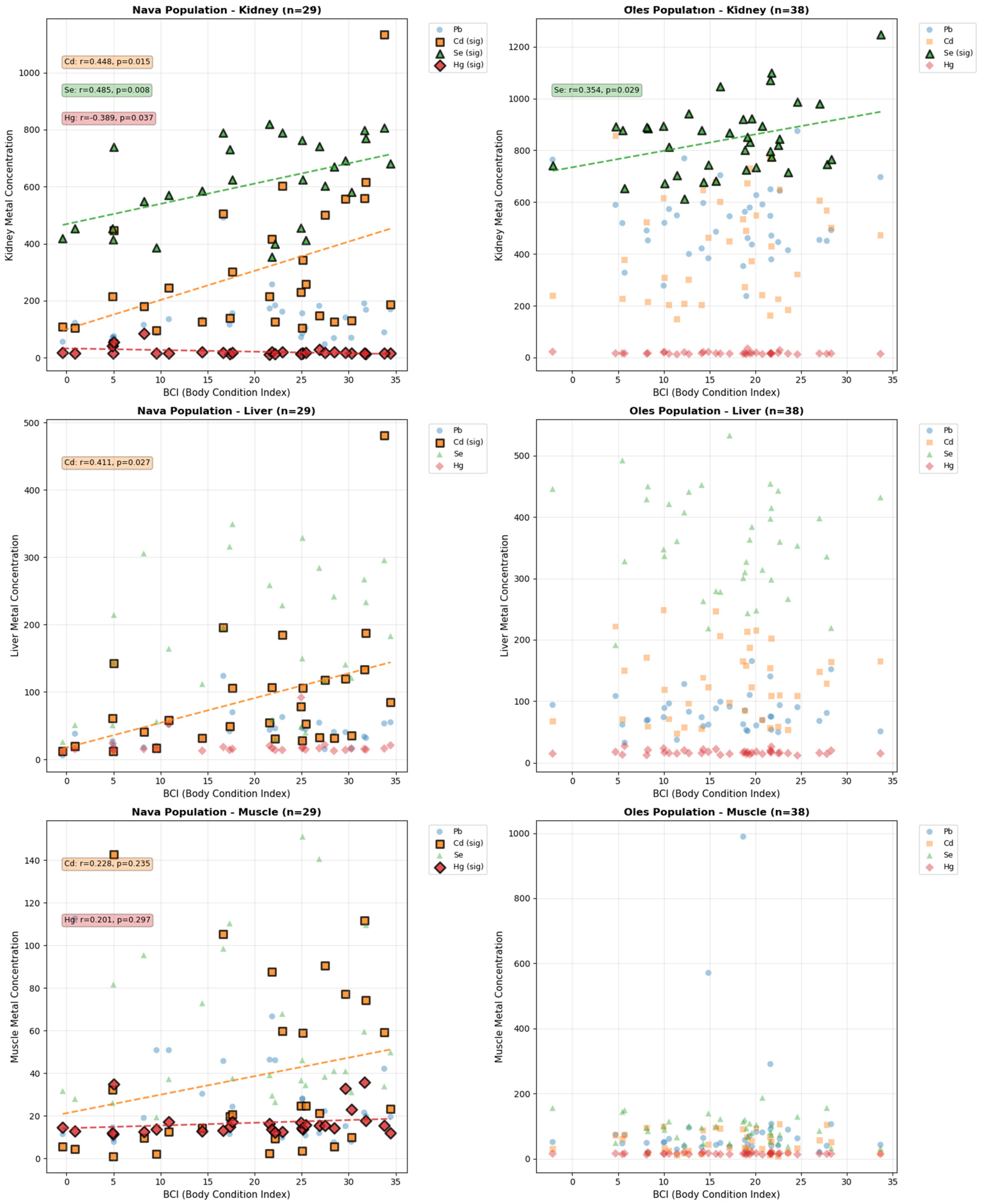

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gall, J.E.; Boyd, R.S.; Rajakaruna, N. Transfer of heavy metals through terrestrial food webs: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Yang, L. Heavy metal contamination in Chinese urban and agricultural soils: A review. Microchem. J. 2010, 94, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovšek, S.; Kopušar, N.; Kryštufek, B. Small mammals as biomonitors of metal pollution: A case study in Slovenia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 4261–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieime, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: Sources, chemistry, risks and remediation strategies. Int. Sch. Res. Notices 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman, K.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Hamers, T.; Wijnhoven, S.; Hendriks, A.J. Meta-analysis of cadmium accumulation in small mammals and bioaccumulation model validation. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Trophic transfer, bioaccumulation, and biomagnification of non-essential hazardous heavy metals and metalloids in food chains/webs—Concepts and implications for wildlife and human health. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2019, 25, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.E.; Yadav, R.R.; Dakshinkar, N.P.; Dhoot, V.M.; Bhojane, G.R.; Naik, M.K.; Shrivastava, P.; Naoghare, P.K.; Krishnamurthi, K. Influence of mercury from fly ash on cattle reared nearby thermal power plants. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 7365–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.; Lee, K.M.; Sawicka-Kapusta, K.; Damek, M.; Cooke, M. The heavy metal content of the teeth of the bank vole (Clethrionomys glareolus) as an exposure marker of environmental pollution in Poland. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 110, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tête, N.; Fritsch, C.; Afonso, E.; Coeurdassier, M.; Lambert, J.-C.; Giraudoux, P.; Scheifler, R. Can body condition and somatic indices assess metal-induced stress in small mammals? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quina, A.S.; Durão, A.F.; Muñoz-Muñoz, F.; Ventura, J.; Mathias, M.L. Population effects of heavy metal pollution in wild Algerian mice (Mus spretus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, C.D. Mammals as monitors of environmental metal levels. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1986, 6, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Chardi, A.; López-Fuster, M.; Nadal, J. Bioaccumulation of Pb, Hg, and Cd in Crocidura russula from the Ebro Delta: Sex and age-dependent variation. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 145, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggeman, S.; van den Brink, N.; Van Praet, N.; Blust, R.; Bervoets, L. Metal exposure and accumulation patterns in free-range cows (Bos taurus) in a contaminated natural area: Influence of spatial and social behavior. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 172, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alonso, M.; Rey-Crespo, F.; Herrero-Latorre, C.; Miranda, M. Identifying sources of metal exposure in dairy farming. Chemosphere 2017, 185, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.D.; Johnson, M.S. Dispersal of heavy metals from abandoned mine workings and their transference through terrestrial food chains. Environ. Pollut. 1978, 16, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.C. Effect of soil pollution with metallic lead pellets on lead bioaccumulation and organ/body weight alterations in small mammals. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1989, 18, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.; Luyssaert, S.; Verbeeren, S.; Vervaeke, P.; Lust, N. Cd and Zn Metal concentrations in small mammals and willow leaves on disposal facilities for dredged material. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 115, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.X.; Shen, L.F.; Liu, J.W.; Wang, Y.W.; Li, S.R. Uptake of toxic heavy metals by rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivated in agricultural soil near Zhengzhou City, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 79, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszkowski, L.; Goszczyński, J.; Truszkowski, J. Trophic relationships of the common vole in cultivated fields. Acta Theriol. 1973, 18, 125–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudoux, P.; Delattre, P.; Quéré, J.P.; Damange, J.P. Rodent population structure in regions of agricultural abandonment. Acta Oecologica 1994, 15, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Heavy metals in grassland food webs: Distribution, bioaccumulation, and transfer. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, N.; Lammertsma, D.; Dimmers, W.; Boerwinkel, M.C.; van der Hout, A. Effects of soil properties on food web accumulation of heavy metals to the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus). Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmori-de la Puente, A.; Ventura, J.; Miñarro, M.; Somoano, A.; Hey, J.; Castresana, J. Divergence time estimation using ddRAD data and an isolation-with-migration model applied to water vole populations of Arvicola. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airoldi, J.P.; Altrocchi, R.; Meylan, A. Le comportement fouisseur du campagnol terrestre, Arvicola terrestris scherman Shaw (Mammalia, Rodentia). Rev. Suisse Zool. 1976, 83, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, R. Food choices of fossorial water voles: Terrarium trials. EPPO Bull. 1988, 18, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, G.G.; Carleton, M.C. Arvicola Lacépède, 1799; Arvicola amphibius (Linnaeus, 1758); Arvicola scherman (Shaw, 1801). In Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; Wilson, D.E., Reeder, D.M., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; pp. 963–966. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudoux, P.; Delattre, P.; Habert, M.; Quéré, J.P.; Deblay, S.; Defaut, R.; Duhamel, R.; Moissenet, M.F.; Salvi, D.; Truchetet, D. Population dynamics of fossorial voles: Land use and landscape perspective. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1997, 66, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoano, A. The role of Arvicola scherman as a crop pest in NW Spain: Since when? Galemys 2020, 32, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoano, A.; Miñarro, M.; Ventura, J. Reproductive potential of a vole pest (Arvicola scherman) in Spanish apple orchards. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 14, e1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudoux, P.; Levret, A.; Afonso, E.; Coeurdassier, M.; Couval, G. Numerical response of predators to large variations of grassland vole abundance and long-term community changes. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 14221–14246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, C.; Cosson, R.P.; Cœurdassier, M.; Raoul, F.; Giraudoux, P.; Crini, N.; de Vaufleury, A.; Scheifler, R. Responses of wild small mammals to a pollution gradient: Host factors influence metal and metallothionein levels. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elturki, M. Assessing Metallothionein 1 Response and Heavy Metal Concentrations in Peromyscus leucopus at the Tar Creek Superfund Site, USA. J. Earth Environ. Sci. Res. 2025, 250, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremyachikh, V.A.; Kvasov, D.A.; Ivanova, E.S. Patterns of mercury accumulation in the organs of bank vole Myodes glareolus (Rodentia, Cricetidae). Biosyst. Divers. 2019, 27, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; Alkheraije, K.A. A review of important heavy metals toxicity with special emphasis on nephrotoxicity and its management in cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1149720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.Q.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, J. Phytoremediation of Cd, Pb, and Zn by Medicago sativa L.: Temporal study. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2015, 47, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Halbrook, R.; Kirkpatrick, R.; Scanlon, P.; Vaughan, M.R.; Veit, H.P. Contaminant accumulation in muskrats from Virginia. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1993, 25, 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- Santolo, G.M. Small mammals collected from selenium-rich sites and three references. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 57, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoano, A.; Ventura, J.; Miñarro, M. Continuous breeding of fossorial water voles in northwestern Spain: Potential impact on apple orchards. J. Vertebr. Biol. 2017, 66, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoano, A.; Bastos-Silveira, C.; Ventura, J.; Miñarro, M.; Heckel, G. A Bocage landscape restricts the gene flow in pest vole populations. Life 2022, 12, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoano, A. Update on the distribution of the fossorial water vole, Arvicola scherman, in Asturias and León, NW Spain. Galemys 2024, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.; Fülling, O.; Malevez, J.; Pelz, H.J. How expensive is vole damage? In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Cultivation Technique and Phytopathological Problems in Organic Fruit-Growing, Weinsberg, Germany, 18–20 February 2008; pp. 330–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dapena, E.; Miñarro, M.; Blázquez, M.D. Organic cider-apple production in Asturias (NW Spain). IOBC/Wprs Bull. 2005, 28, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-López, E. Análisis Geoestadísticos de Niveles Geogénicos de Metales Pesados en Suelos de Asturias. Master’s Thesis, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Resolución de 20 de Marzo de 2014 Sobre Niveles Genéricos de Referencia para Metales Pesados en Suelos del Principado de Asturias; Boletín Oficial del Principado de Asturias: Oviedo, Spain, 2014.

- Real Decreto 9/2005, de 14 de enero, por el que se Establece la Relación de Actividades Potencialmente Contaminantes del Suelo y los Criterios y Estándares para la Declaración de Suelos Contaminados; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2005.

- Real Decreto 409/2008, de 28 de Marzo, por el que se Establece el Programa Nacional de Control de las Plagas del Topillo de Campo, «Microtus arvalis» (Pallas), y Otros Microtinos; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2008.

- Real Decreto 53/2013, de 1 de Febrero, por el que se Establecen las Normas Básicas Aplicables Para la Protección de los Animales Utilizados en Experimentación y Otros Fines Científicos, Incluyendo la Docencia; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2013.

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- Peig, J.; Green, A.J. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: The scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 2009, 118, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 1989, 43, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, D. Trace metal analysis in herbs and teas using PCA. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyuan, W.; Dengfeng, W.; Huiping, Z.; Zhiping, Q. Soil heavy metal pollution assessment via PCA and geoaccumulation index. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 10, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023.

- Forcada, S.; Menéndez-Miranda, M.; Boente, C.; Rodríguez Gallego, J.L.; Costa-Fernández, J.M.; Royo, L.J.; Soldado, A. Impact of potentially toxic compounds in cow milk: How industrial activities affect animal primary productions. Foods 2023, 12, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micó, C.; Recatalá, L.; Peris, M.; Sánchez, J. Assessing heavy metal sources in agricultural soils of an European Mediterranean area by multivariate analysis. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berny, P.; Vilagines, L.; Cugnasse, J.M.; Mastain, O.; Chollet, J.Y.; Joncour, G.; Razin, M. Vigilance Poison: Illegal poisoning and lead intoxication are the main factors affecting avian scavenger survival in the Pyrenees (France). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 118, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukal, J.; Pikula, J.; Bandouchova, H. Bats as bioindicators of heavy metal pollution: History and prospect. Mamm. Biol. 2015, 80, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imeri, R.; Kullaj, E.; Millaku, L. Heavy metal distribution in apples near industrial zones. J. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 20, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, C.; Stihi, C.; Barbes, L.; Chilian, A.; Chelarescu, D.E. Studies concerning heavy metals accumulation of Carduus nutans L. and Taraxacum officinale as potential soil bioindicator species. Revista de Chimie 2013, 64, 754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, A.; Hale, W.H.G.; Dixon, J.M. Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medic. as a biomonitor of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 226, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Montes, M.; De la Rosa, G.; Corral-Diaz, B. Bioaccumulation of Cd, Cr and Cu by Convolvulus arvensis: Effects on growth and nutrition. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 92, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, S.E.; Barnes, M.C.; George, H.S.; Joshee, L.; Jeon, B.; Scircle, A.; Black, O.; Cizdziel, J.; Smith, B.E.; Bridges, C.C. Exposure to mixtures of mercury, cadmium, lead, and arsenic alters the disposition of single metals in tissues of Wistar rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 2018, 81 Pt A, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellingen, R.M.; Myrmel, L.S.; Rasinger, J.D.; Lie, K.K.; Bernhard, A.; Madsen, L.; Nøstbakken, O.J. Dietary selenomethionine reduce mercury tissue levels and modulate methylmercury induced proteomic and transcriptomic alterations in hippocampi of adolescent BALB/c mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharaky, A.S.; Newairy, A.A.; Badreldeen, M.M.; Eweda, S.M.; Sheweita, S.A. Protective role of selenium against renal toxicity induced by cadmium in rats. Toxicology 2007, 235, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.A.; Domouky, A.M.; Akmal, F.; El-Wafaey, D.I. Possible role of selenium in ameliorating lead-induced neurotoxicity in the cerebrum of adult male rats: An experimental study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delattre, P.; Giraudoux, P. Le Campagnol Terrestre. Prévention et Contrôle des Populations; Éditions Quæ: Versailles Cedex, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, M.I.; Green, I.D.; Khan, F.A. Trace metal contamination: Transfer and fate in terrestrial invertebrate food chains. Food Webs 2019, 20, e00116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, R.P.; Ebbs, S.D. Cadmium accumulation in Panicum clandestinum and potential trophic transfer to rodents. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 148, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, S.; Bansal, M.P. Selenium status influences male mice reproduction via NFkB modulation. Biometals 2007, 20, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nava | Oles | Mann–Whitney U Results | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Metal | N | Mean | ± SD | Min | Max | N | Mean | ± SD | Min | Max | U | p Corrected |

| Liver | Pb | 30 | 39.29 | 22.26 | 5.66 | 123.57 | 40 | 85.02 | 37.26 | 32.54 | 230.10 | 108.00 | <0.0001 |

| Cd | 30 | 87.91 | 91.84 | 11.55 | 480.74 | 40 | 130.03 | 58.27 | 47.16 | 248.02 | 299.00 | <0.0001 | |

| Se | 30 | 172.82 | 100.94 | 25.35 | 349.11 | 40 | 353.83 | 85.43 | 191.40 | 532.63 | 110.00 | <0.0001 | |

| Hg | 30 | 19.51 | 15.34 | 11.66 | 91.50 | 40 | 17.18 | 3.39 | 12.06 | 27.05 | 486.00 | 0.1760 | |

| Kidney | Pb | 30 | 136.36 | 83.43 | 47.06 | 490.86 | 40 | 518.04 | 133.80 | 237.28 | 874.81 | 20.00 | <0.0001 |

| Cd | 30 | 297.58 | 234.57 | 49.40 | 1133.12 | 40 | 446.74 | 198.81 | 147.63 | 855.46 | 315.00 | 0.001 | |

| Se | 30 | 606.17 | 150.51 | 353.35 | 819.17 | 40 | 840.69 | 131.84 | 611.61 | 1246.61 | 142.00 | <0.0001 | |

| Hg | 30 | 21.03 | 14.84 | 11.42 | 84.01 | 40 | 17.05 | 4.25 | 12.02 | 34.50 | 544.00 | 0.5060 | |

| Muscle | Pb | 30 | 26.92 | 22.99 | 3.36 | 112.52 | 40 | 97.30 | 171.12 | 18.20 | 989.20 | 181.00 | <0.0001 |

| Cd | 30 | 37.24 | 39.38 | 0.98 | 142.56 | 40 | 53.06 | 36.79 | 7.03 | 172.40 | 395.00 | 0.015 | |

| Se | 30 | 55.95 | 35.53 | 19.29 | 150.99 | 40 | 93.39 | 38.91 | 31.72 | 186.89 | 254.00 | <0.0001 | |

| Hg | 30 | 16.58 | 6.53 | 11.24 | 35.84 | 40 | 15.49 | 2.22 | 12.17 | 21.26 | 523.00 | 0.3610 | |

| Metal reference values | Pb | 18,545.00 | 25,102.00 | 25,102.00 | 35,981.00 | ||||||||

| Cd | 296.34 | 418.14 | 296.34 | 700.12 | |||||||||

| Hg | 120.37 | 135.40 | 170.91 | 294.79 | |||||||||

| Tissue | PC | Eigenvalue | % Variation | Factor-Variable Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | Se | Hg | ||||

| Liver | PC1 | 1.824 | 45.59 | 0.391 | 0.215 | 0.338 | 0.056 |

| PC2 | 1.060 | 26.51 | 0.055 | 0.150 | 0.146 | 0.649 | |

| PC3 | 0.714 | 17.86 | 0.019 | 0.620 | 0.067 | 0.294 | |

| PC4 | 0.402 | 10.04 | 0.535 | 0.015 | 0.448 | 0.002 | |

| Kidney | PC1 | 2.177 | 54.43 | 0.342 | 0.288 | 0.350 | 0.020 |

| PC2 | 1.044 | 26.09 | 0.013 | 0.036 | 0.079 | 0.872 | |

| PC3 | 0.513 | 12.83 | 0.282 | 0.630 | 0.017 | 0.071 | |

| PC4 | 0.266 | 6.65 | 0.362 | 0.046 | 0.554 | 0.037 | |

| Muscle | PC1 | 1.401 | 35.02 | 0.188 | 0.439 | 0.109 | 0.264 |

| PC2 | 1.179 | 29.47 | 0.012 | 0.026 | 0.593 | 0.369 | |

| PC3 | 0.931 | 23.27 | 0.750 | 0.210 | 0.005 | 0.035 | |

| PC4 | 0.489 | 12.24 | 0.050 | 0.325 | 0.293 | 0.332 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Somoano, A.; Adalid, R.; Ventura, J.; Muñoz-Muñoz, F.; Fuentes, M.V.; Menéndez-Miranda, M.; Miñarro, M. Bioaccumulation of Potential Harmful Elements in Fossorial Water Voles Inhabiting Non-Polluted Crops. Toxics 2025, 13, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121083

Somoano A, Adalid R, Ventura J, Muñoz-Muñoz F, Fuentes MV, Menéndez-Miranda M, Miñarro M. Bioaccumulation of Potential Harmful Elements in Fossorial Water Voles Inhabiting Non-Polluted Crops. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121083

Chicago/Turabian StyleSomoano, Aitor, Roser Adalid, Jacint Ventura, Francesc Muñoz-Muñoz, Màrius Vicent Fuentes, Mario Menéndez-Miranda, and Marcos Miñarro. 2025. "Bioaccumulation of Potential Harmful Elements in Fossorial Water Voles Inhabiting Non-Polluted Crops" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121083

APA StyleSomoano, A., Adalid, R., Ventura, J., Muñoz-Muñoz, F., Fuentes, M. V., Menéndez-Miranda, M., & Miñarro, M. (2025). Bioaccumulation of Potential Harmful Elements in Fossorial Water Voles Inhabiting Non-Polluted Crops. Toxics, 13(12), 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121083