Sentinel Equines in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals and Hematological Biomarkers as Indicators of Environmental Contamination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Samping Design

2.2. Sampling of Environmental and Biological Matrices

2.2.1. Mane and Tail Hair Sample Collection

2.2.2. Hoof Sample Collection

2.2.3. Serum Sample Collection

2.2.4. Synovial Fluid Sample Collection

2.2.5. Water Sample Collection

2.2.6. Green Grass and Dried Hay Sample Collection

2.2.7. Concentrate Sample Collection

2.2.8. Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Preparation, Digestion, and Analytical Determination of Metals

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

Mane and Tail Hair Samples

Hoof Samples

Serum Samples

Synovial Fluid Samples

Water Samples

Green Grass and Dried Hay Samples

Concentrate Feed Samples

Soil Samples

2.3.2. Sample Digestion

2.3.3. Analytical Determination of Metals

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Heavy Metal Profiles in Equine Mane and Tail Hair from Polluted and Control Areas

3.2. Heavy Metal Profiles in Equine Hooves from Polluted and Control Areas

3.3. Heavy Metal Profiles in Equine Serum from Polluted and Control Area

| Sample Codes/Heavy Metals | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | Ni | Co | As | Cr | Hg | Spearman’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone I encompass the areas of the former tailing’s ponds at Bozânta Mare, Săsar, and Nistru | |||||||||||

| HF-W-TMBTP-O1 | 7.43 ± 0.16 c | 131.93 ± 6.12 b | 4.70 ± 0.18 a | <LOD | 0.85 ± 0.10 e | 0.50 ± 0.02 h | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.90 | 0.037 |

| HF-S-TMBTP-O1 | 5.40 ± 0.10 d | 110.33 ± 3.25 b | 3.60 ± 0.20 a | <LOD | 0.98 ± 0.10 e | 0.41 ± 0.03 k | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.80 | 0.104 |

| HF-W-RS-O1 | 7.60 ± 0.20 c | 122.44 ± 3.51 b | 4.70 ± 0.23 a | <LOD | 1.07 ± 0.13 d | 0.53 ± 0.02 g | <LOD | 0.32 ± 0.06 c | <LOD | −0.90 | 0.0048 |

| HF-S-RS-O1 | 4.80 ± 0.90 e | 108.68 ± 6.05 b | 3.60 ± 0.23 a | <LOD | 1.13 ± 0.13 d | 0.46 ± 0.09 i | <LOD | 0.23 ± 0.02 d | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0039 |

| HF-W-TMN-O1 | 6.80 ± 0.66 d | 128.53 ± 6.66 b | 6.60 ± 0.49 a | <LOD | 1.53 ±0.20 c | 0.56 ± 0.02 f | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.90 | 0.037 |

| HF-S-TMN-O1 | 5.00 ± 1.21 d | 108.76 ± 6.57 b | 5.60 ± 0.36 a | <LOD | 1.60 ± 0.18 c | 0.46 ± 0.02 j | <LOD | 0.21 ± 0.01 e | <LOD | −0.83 | 0.0416 |

| Zone II includes the areas of the former mines: Herja, Ilba, Șuior, Nistru, and UP Central Flotation | |||||||||||

| HF-W-TMH-O1 | 9.10 ± 1.18 b | 157.65 ± 7.47 a | 6.50 ± 0.46 a | <LOD | 1.83 ± 0.25 b | 0.63 ± 0.03 d | <LOD | 0.61 ± 0.15 a | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0048 |

| HF-S-TMH-O1 | 7.60 ± 1.35 c | 144.79 ± 12.29 a | 5.70 ± 0.53 a | <LOD | 1.62 ± 0.23 c | 0.52 ± 0.03 g | <LOD | 0.52 ± 0.08 b | <LOD | −0.89 | 0.0188 |

| HF-W-TMH-O2 | 10.20 ± 1.91 a | 169.98 ± 3.99 a | 6.40 ± 0.48 a | <LOD | 1.95 ± 0.25 a | 0.68 ± 0.06 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0374 |

| HF-S-TMH-O2 | 8.10 ± 2.11 c | 157.82 ± 9.21 a | 5.80 ± 0.48 a | <LOD | 1.78 ± 0.23 b | 0.56 ± 0.03 f | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0365 |

| HF-W-CI-O1 | 8.60 ± 1.65 b | 167.62 ± 8.53 a | 6.30 ± 0.36 a | <LOD | 1.58 ± 0.20 c | 0.64 ± 0.01 d | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0372 |

| HF-S-CI-O1 | 7.10 ±1.61 c | 147.94 ± 10.73 a | 5.60 ± 0.56 a | <LOD | 1.73 ± 0.20 b | 0.57 ± 0.04 f | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.92 | 0.0341 |

| HF-W-CI-O2 | 11.00 ± 2.00 b | 171.11 ± 11.47 a | 6.20 ± 0.36 a | <LOD | 1.65 ± 0.08 b | 0.67 ± 0.03 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0064 |

| HF-S-CI-O2 | 6.70 ± 2.03 d | 146.38 ± 13.72 a | 5.70 ± 0.46 a | <LOD | 1.82 ± 0.19 b | 0.56 ± 0.03 f | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0376 |

| HF-W-CȘ-O1 | 8.80 ± 1.87 b | 176.77 ± 9.73 a | 6.50 ± 0.46 a | <LOD | 2.03 ± 0.34 a | 0.69 ± 0.07 b | <LOD | 0.19 ± 0.03 e | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0054 |

| HF-S-CȘ-O1 | 6.60 ± 1.87 d | 148.19 ± 13.19 a | 5.90 ± 0.04 a | <LOD | 2.18 ± 0.09 a | 0.58 ± 0.01 e | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0374 |

| HF-W-CȘ-O2 | 9.70 ± 2.33 b | 172.49 ± 14.91 la | 5.80 ± 0.43 a | <LOD | 2.10 ± 0.23 a | 0.72 ± 0.03 a | <LOD | 0.25 ± 0.06 d | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0048 |

| HF-S-CȘ-O2 | 7.93 ± 2.47 c | 144.10 ± 14.85 a | 5.80 ± 0.43 a | <LOD | 2.23 ± 0.25 a | 0.60 ± 0.10 d | <LOD | 0.19 ± 0.03 e | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0048 |

| HF-W-CȘ-O3 | 8.10 ± 1.87 c | 160.51 ± 17.57 a | 6.40 ± 0.46 a | <LOD | 2.17 ± 0.23 a | 0.74 ± 0.09 a | <LOD | 0.26 ± 0.08 d | <LOD | −0.98 | 0.0051 |

| HF-S-CȘ-O3 | 6.30 ± 1.92 d | 138.02 ± 17.92 b | 5.95 ± 0.38 a | <LOD | 2.28 ± 0.11 a | 0.60 ± 0.14 d | <LOD | 0.28 ± 0.14 d | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0365 |

| HF-W-TNN-O1 | 9.50 ± 1.95 b | 161.45 ± 17.76 a | 6.45 ± 0.21 a | <LOD | 1.93 ± 0.18 a | 0.58 ± 0.08 e | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.92 | 0.0341 |

| HF-S-TNN-O1 | 7.20 ± 2.33 c | 143.75 ± 17.36 a | 5.65 ± 0.58 a | <LOD | 2.07 ± 0.23 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 i | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.98 | 0.0051 |

| HF-W-UPCFBM-O1 | 10.40 ± 2.17 a | 164.81 ± 11.28 a | 6.25 ± 0.16 a | <LOD | 2.12 ± 0.07 a | 0.48 ± 0.08 h | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.94 | 0.0049 |

| HF-S-UPCFBM-O1 | 7.80 ± 2.00 c | 147.68 ± 13.02 a | 5.85 ± 0.69 a | <LOD | 2.25 ± 0.31 a | 0.43 ± 0.02 j | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0372 |

| Zone III includes the control area | |||||||||||

| HF-W-T-O1-O10 | 2.67 ± 0.55 f | 75.06 ± 6.81 c | 1.41 ± 0.09 b | <LOD | 0.52 ± 0.08 f | 0.12 ± 0.02 k | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0374 |

| HF-S-T-O1-O10 | 2.83 ± 0.55 f | 50.63 ± 8.53 c | 1.12 ± 0.13 b | <LOD | 0.60 ± 0.10 f | 0.09 ± 0.01 k | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | −0.9 | 0.0375 |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Polluted Area vs. Control Area) | 5.34 0.020 | 15.21 0.0005 | 29.30 0.001 | – | 5.33 0.021 | 5.35 0.0207 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Sample Type (Wall vs. Sole) | 11.22 0.0008 | 4.75 0.0293 | 7.32 0.001 | – | 0.35 0.56 | 5.34 0.0208 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r1) p-value (p1) | 0.70 0.0001 | −0.17 0.4011 | 0.867 0.001 | – | 0.27 0.176 | −0.034 0.871 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r2) p-value (p2) | 0.46 0.017 | 0.25 0.2120 | 0.433 0.001 | – | 0.12 0.566 | 0.034 0.871 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r3) p-value (p3) | 0.462 0.017 | −0.44 0.0260 | 0.969 0.001 | – | 0.001 0.999 | 0.190 0.353 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Levels in Horse Hoof, Including Samples from Control Areas | |||||||||||

| Non-polluted area | |||||||||||

| Hoof wall specimens harvested from the external surface of the hoof capsule of horses | |||||||||||

| Tocci et al. 2017 [27] ppm | 5.7 | 131.5 | 2.7 | – | 5.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hoof sole specimens harvested from the solar surface of the hoof capsule of horses | |||||||||||

| Tocci et al. 2017 [27] ppm | 3.6 | 102.1 | 1.7 | – | 1.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hoof specimens harvested from the external surfaces of the hoof capsule of horses | |||||||||||

| Rueda-Carrillo et al. 2022 [20] µg/g | 1.80 | 79.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Aragona et al. 2024 [37] mg/kg | 0.058 | 1.077 | 0.002 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Stachurska et al. 2011 [46] mg/kg | 1.10 | – | 0.39 | 0.00 | – | – | – | 1.31 | – | – | – |

3.4. Heavy Metal Profiles in Equine Synovial Fluid from Polluted and Control Areas

3.5. Heavy Metal Profiles in Water Samples from Polluted and Control Areas

3.6. Heavy Metal Profiles in Vegetation (Grass and Hay) from Polluted and Control Areas

| Sample Codes/Heavy Metals | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | Ni | Co | As | Cr | Hg | Spearman’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone I encompass the areas of the former tailing’s ponds at Bozânta Mare, Săsar, and Nistru | |||||||||||

| SE-TMBTP-O1 | 7.54 ± 0.11 c | 751.61 ± 12.67 k | <LOD | <LOD | 1.53 ± 0.10 c | 0.22 ± 0.03 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-RS-O1 | 5.28 ± 0.16 c | 661.30 ± 11.11 l | <LOD | <LOD | 1.40 ± 0.09 d | 0.27 ± 0.06 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-TMN-O1 | 7.60 ± 0.10 c | 766.19 ± 7.16 j | <LOD | <LOD | 1.57 ± 0.07 c | 0.31 ± 0.03 b | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Zone II includes the areas of the former mines: Herja, Ilba, Șuior, Nistru, and UP Central Flotation | |||||||||||

| SE-TMH-O1 | 9.10 ± 0.15 a | 788.67 ± 6.91 b | <LOD | <LOD | 1.83 ± 0.12 a | 0.35 ± 0.15 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-TMH-O2 | 8.93 ± 0.13 b | 786.17 ± 11.67 c | <LOD | <LOD | 1.78 ± 0.11 a | 0.32 ± 0.04 b | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-CI-O1 | 10.23 ± 0.15 a | 801.48 ± 3.64 a | <LOD | <LOD | 1.57 ± 0.08 c | 0.29 ± 0.06 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-CI-O2 | 8.10 ± 0.10 b | 772.93 ± 7.90 g | <LOD | <LOD | 1.53 ± 0.07 c | 0.30 ± 0.01 c | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-CȘ-O1 | 8.57 ± 1.16 b | 778.22 ± 10.84 e | <LOD | <LOD | 1.63 ± 0.10 b | 0.37 ± 0.08 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-CȘ-O2 | 8.10 ± 0.10 b | 766.72 ± 4.06 i | <LOD | <LOD | 1.59 ± 0.10 c | 0.36 ± 0.04 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-CȘ-O3 | 8.20 ± 0.23 b | 776.00 ± 9.09 f | <LOD | <LOD | 1.61 ± 0.10 b | 0.34 ± 0.01 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-TNN-O1 | 7.76 ± 0.07 c | 771.29 ± 14.22 h | <LOD | <LOD | 1.64 ± 0.09 b | 0.32 ± 0.02 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SE-UPCFBM-O1 | 8.38 ± 0.08 b | 780.08 ± 4.28 d | <LOD | <LOD | 1.67 ± 0.16 b | 0.32 ± 0.04 a | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Zone III includes the control area | |||||||||||

| SE-T-O1-O10 | 2.68 ± 0.02 d | 599.99 ± 7.34 m | <LOD | <LOD | 0.17 ± 0.04 e | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Polluted Area vs. Control Area) | 2.58 0.108 | 2.84 0.124 | – | – | 17.28 0.001 | 17.29 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r1) p-value (p1) | 0.464 0.111 | 0.463 0.111 | – | – | 0.460 0.133 | 0.492 0.104 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r2) p-value (p2) | 0.472 0.103 | 0.472 0.109 | – | – | 0.907 0.001 | 0.907 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Levels in Horse Serum Samples, Including Samples from Control Areas | |||||||||||

| Non-polluted area | |||||||||||

| Oztas et al. (2025) [48] µg/mL | – | – | 1.29 | 0.27 | – | – | 0.26 | – | – | – | – |

| Brummer-Holder et al. (2022) [30] mg/L | – | – | BLD | BLD | BLD | – | BLD | – | – | – | – |

| Polluted area | |||||||||||

| Maia et al. (2006) [49] µg/mL | – | – | 0.021 | 0.010 | 0.003 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sample Codes/Heavy Metals | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | Ni | Co | As | Cr | Hg | Spearman’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone I encompass the areas of the former tailing’s ponds at Bozânta Mare, Săsar, and Nistru | |||||||||||

| SF-TMBTP-O1 | 8.25 ± 2.85 a | 336.03 ± 15.78 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-RS-O1 | 9.05 ± 3.22 a | 307.29 ± 12.16 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-TMN-O1 | 5.54 ± 0.97 b | 271.41 ± 21.86 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Zone II includes the areas of the former mines: Herja, Ilba, Șuior, Nistru, and UP Central Flotation | |||||||||||

| SF-TMH-O1 | 8.23 ± 1.08 a | 141.87 ± 14.97 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-TMH-O2 | 5.59 ± 1.05 b | 394.63 ± 7.40 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-CI-O1 | 4.42 ± 2.47 c | 222.78 ± 20.87 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-CI-O2 | 9.07 ± 1.71 a | 392.23 ± 24.07 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-CȘ-O1 | 4.57 ± 0.96 b | 108.87 ± 13.06 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-CȘ-O2 | 6.51 ± 2.00 b | 288.56 ± 33.51 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-CȘ-O3 | 3.37 ± 1.97 d | 296.30 ± 24.85 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-TNN-O1 | 4.70 ± 2.82 c | 217.92 ± 21.87 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| SF-UPCFBM-O1 | 3.49 ± 1.32 d | 238.76 ± 25.25 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Zone III includes the control area | |||||||||||

| SF-T-O1-O10 | 5.09 ± 1.36 b | 127.50 ± 25.25 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | – | – |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Polluted Area vs. Control Area) | 5.33 0.021 | 1.79 0.181 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r1) p-value (p1) | 0.460 0.133 | 0.386 0.193 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r2) p-value (p2) | 0.492 0.104 | −0.014 0.965 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

3.7. Heavy Metal Profiles in Equine Feed Concentrates (Corn) from Polluted and Control Areas

3.8. Heavy Metal Profiles in Soil Samples from Polluted and Control Areas

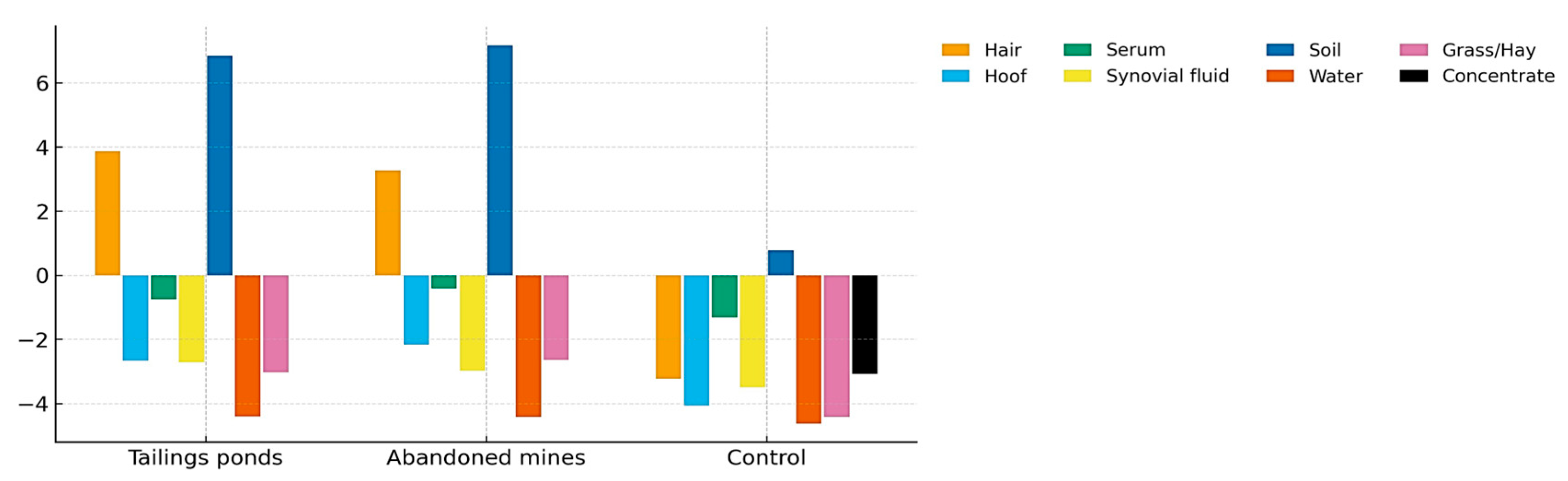

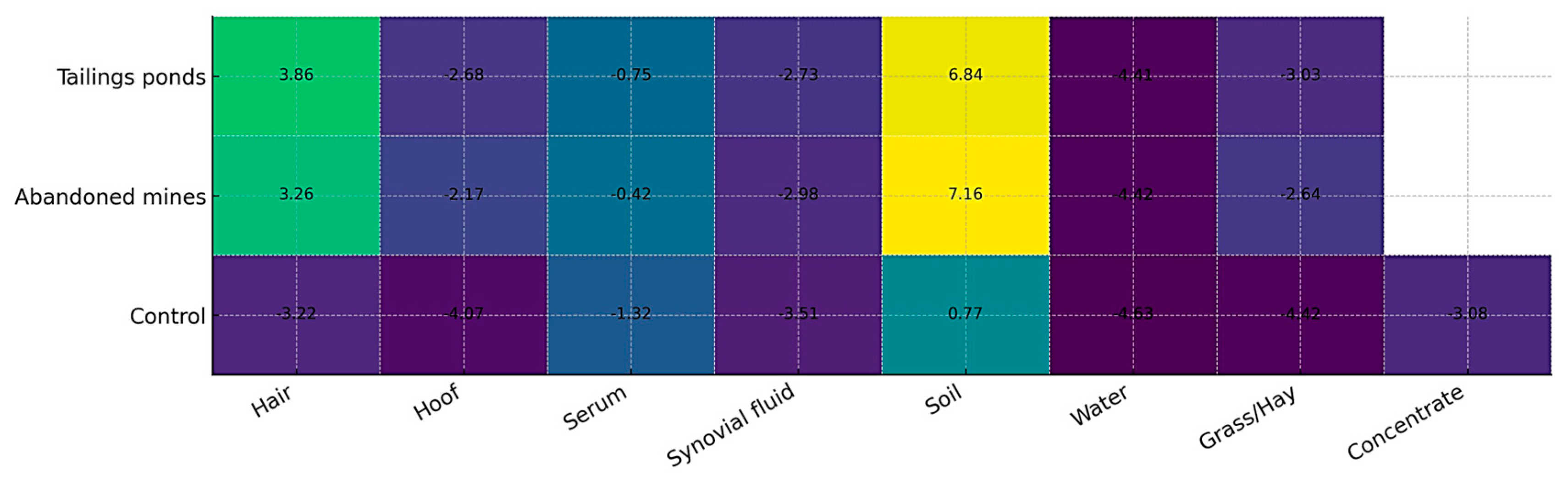

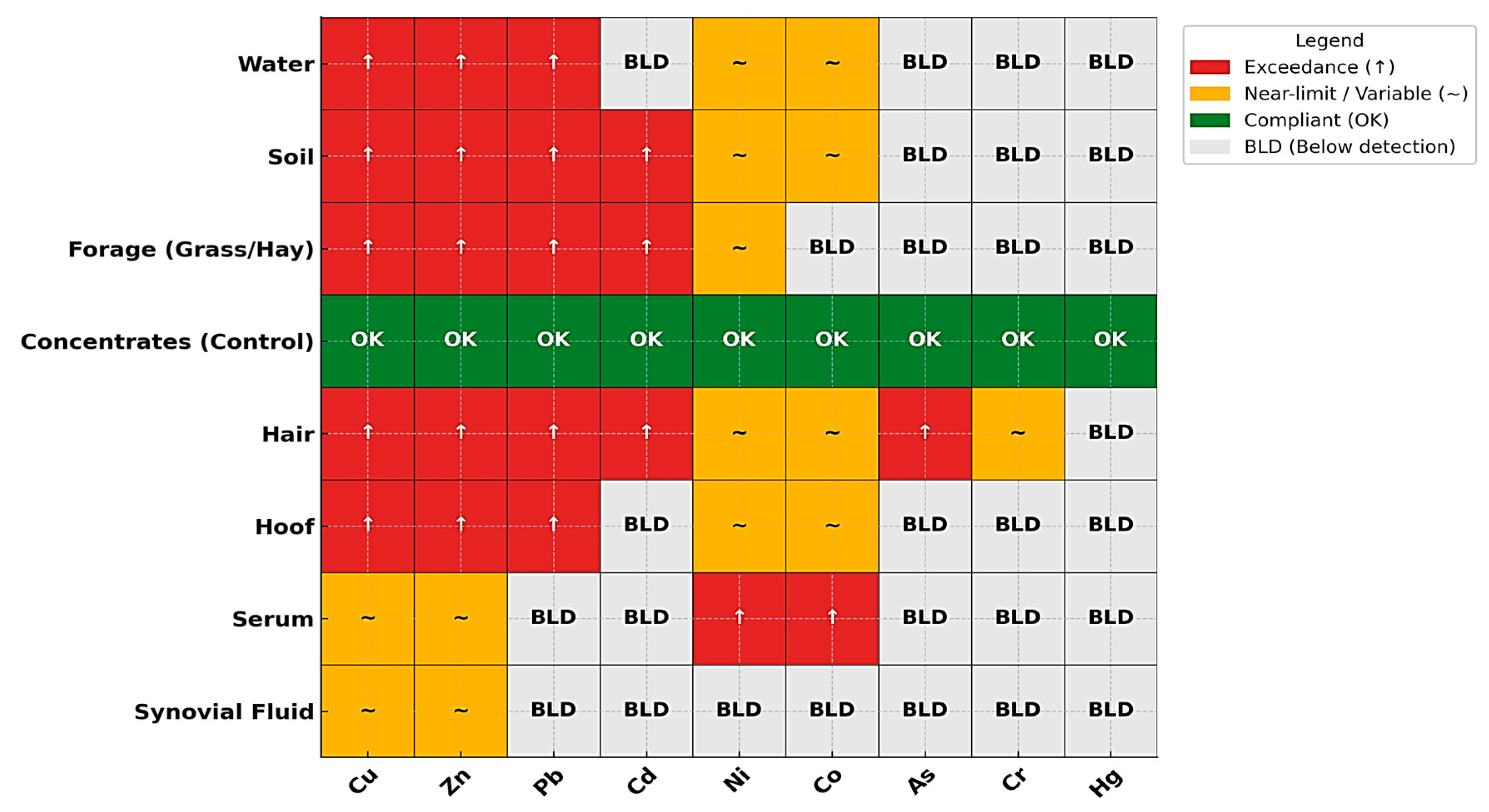

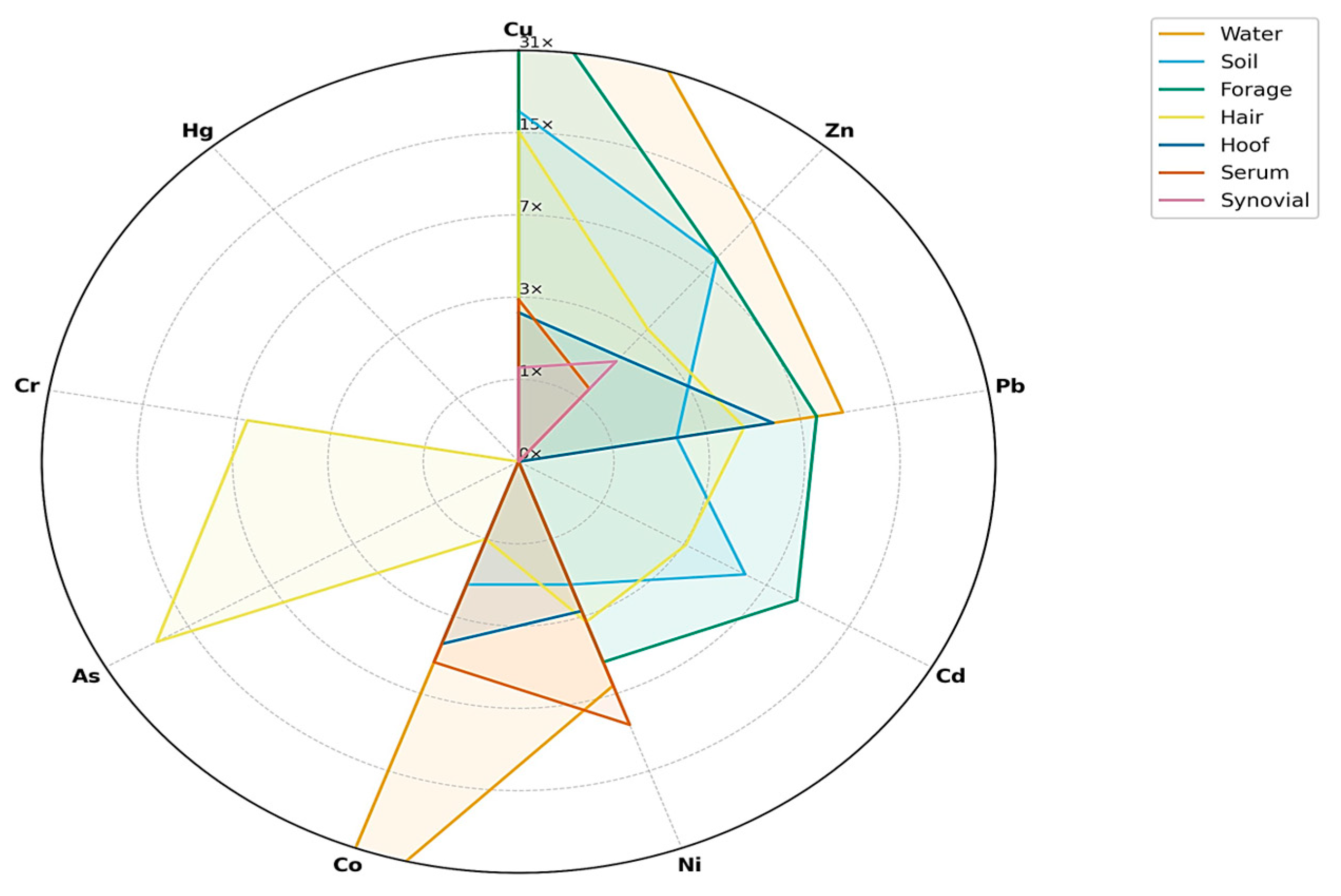

3.9. Cumulative Pollution Index (CPI) Across Environmental and Biological Matrices

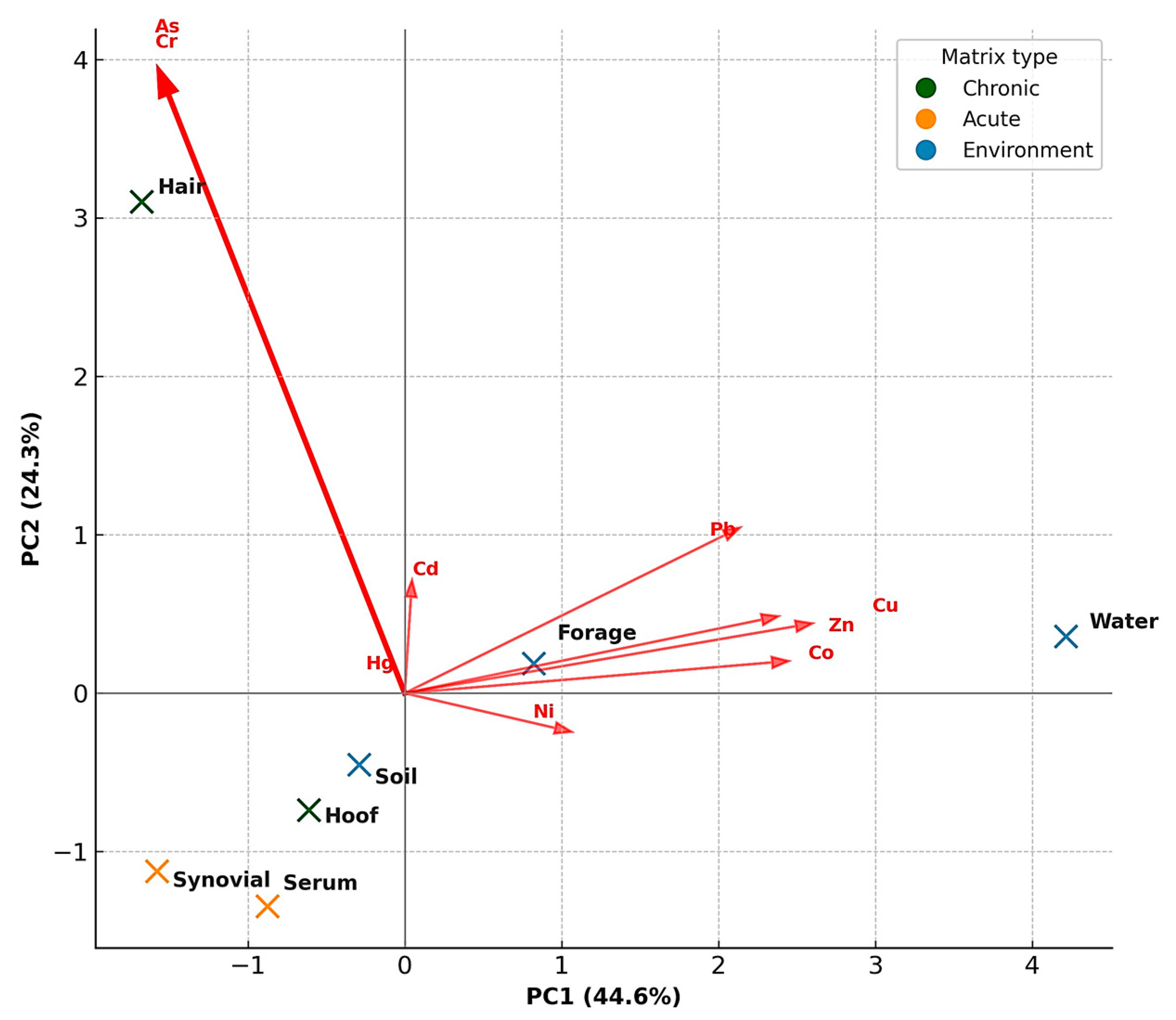

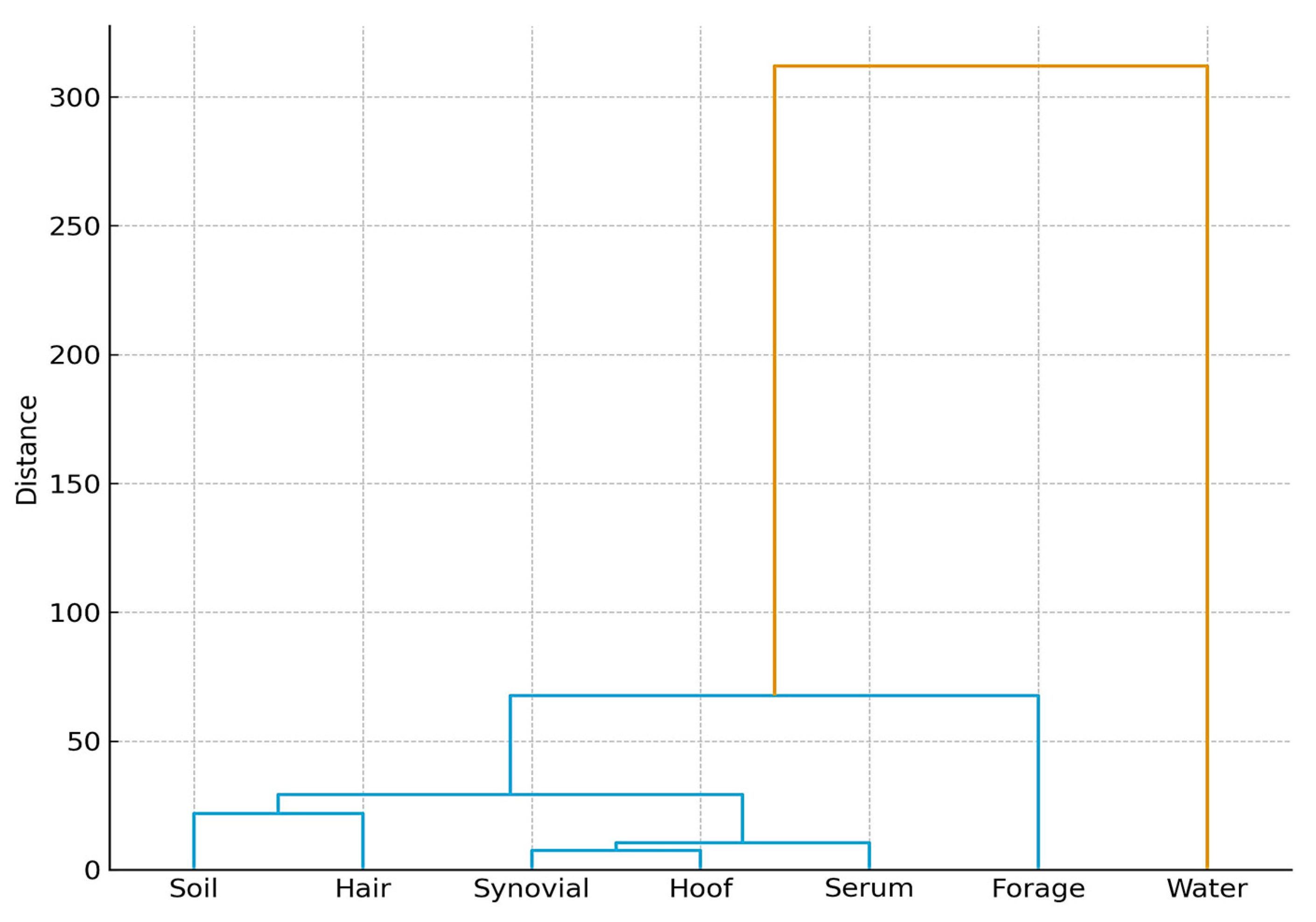

3.10. Integration of Environmental and Biological Matrices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| As | Arsenic |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Co | Cobalt |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| Hg | Mercury |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Pb | Lead |

| Zn | Zinc |

| ICP–MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry |

| SF | Synovial Fluid |

| SE | Serum |

| HA | Hair |

| HF | Hoof |

| W | Water |

| G | Grass |

| H | Hay |

| CF | Concentrate Feed |

| S | Soil |

| BLD | Below Detection Limit |

| LoQ | Limit of Quantification |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| CPI | Cumulative Pollution Index |

References

- Wiedmann, T.; Lenzen, M.; Keyßer, L.T.; Steinberger, J.K. Scientists’ Warning on Affluence. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragona, F.; Giannetto, C.; Piccione, G.; Licata, P.; Deniz, Ö.; Fazio, F. Hair and Blood Trace Elements (Cadmium, Zinc, Chrome, Lead, Iron and Copper) Biomonitoring in the Athletic Horse: The Potential Role of Haematological Parameters as Biomarkers. Animals 2024, 14, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Mukherjee, A.B. Trace Elements from Soil to Human; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Yang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, L. Accumulation, Translocation, and Assessment of Heavy Metals in the Soil-Rice Systems near a Mine-Impacted Region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 32221–32230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Metals, Minerals and Microbes: Geomicrobiology and Bioremediation. Microbiology (Reading) 2010, 156, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.N.V.; Sajwan, K.S.; Naidu, R. Trace Elements in the Environment: Biogeochemistry, Biotechnology, and Bioremediation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780367391966. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B.J. Heavy Metals in Soils; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nriagu, J.O.; Pacyna, J.M. Quantitative Assessment of Worldwide Contamination of Air, Water and Soils by Trace Metals. Nature 1988, 333, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. Mol. Clin. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals—Concepts and Applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecié, M.; Jachimowicz, K.; Winiarska-Mieczan, A.; Cygan-Szczegielniak, D.; Stasiak, K. Concentration of Selected Essential and Toxic Trace Elements in Horse Hair as an Important Tool for the Monitoring of Animal Exposure and Health. Animals 2022, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boening, D.W. Ecological Effects, Transport, and Fate of Mercury: A General Review. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järup, L. Hazards of Heavy Metal Contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Welch, A.H.; Stollenwerk, K.G.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Bundschuh, J.; Panaullah, G. Arsenic in the Environment: Biology and Chemistry. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 379, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casteel, S.W. Metal Toxicosis in Horses. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2001, 17, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, M.V.; Fontes, M.P.F.; Fernandes, R.B.A. Heavy Metals in Equine Biological Components. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2014, 43, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Frio, A.; Jarman, T. Heavy Metal Contamination of Animal Feedstuffs—A New Survey. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 5, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, Mechanism and Health Effects of Some Heavy Metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava, V.; Licata, P.; Biondi, V.; Catone, G.; Gugliandolo, E.; Pugliese, M.; Passantino, A.; Crupi, R.; Aragona, F. Horse Whole Blood Trace Elements from Different Sicily Areas: Biomonitoring of Environmental Risk. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 3086–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Carrillo, G.; Rosiles-Martínez, R.; Hernández-García, A.I.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Trigo-Tavera, F.J. Preliminary Study on the Connection Between the Mineral Profile of Horse Hooves and Tensile Strength Based on Body Weight, Sex, Age, Sampling Location, and Riding Disciplines. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 763935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, R.L. Assessment of Trace Mineral Status of Ruminants: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggeman, S.; Van Den Brink, N.; Van Praet, N.; Blust, R.; Bervoets, L. Metal Exposure and Accumulation Patterns in Free-Range Cows (Bos taurus) in a Contaminated Natural Area: Influence of Spatial and Social Behavior. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 172, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Cicero, N.; Piccione, G.; Giannetto, C.; Licata, P. Blood Response to Mercury Exposure in Athletic Horse from Messina, Italy. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2020, 84, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elghany, S.M.; Mohammed, M.A.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Saud Saad, F.S.; Sallam, K.I. Health Risk Assessment of Exposure to Heavy Metals from Sheep Meat and Offal in Kuwait. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljohani, A.S.M. Heavy Metal Toxicity in Poultry: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1161354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Aragona, F.; Piccione, G.; Arfuso, F.; Giannetto, C. Lithium Concentration in Biological Samples and Gender Difference in Athletic Horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2022, 117, 104081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocci, R.; Sargentini, C.; Martini, A.; Andrenelli, L.; Pezzati, A.; Benvenuti, D.; Giorgetti, A. Hoof Quality of Anglo-Arabian and Haflinger Horses. J. Vet. Res. 2017, 61, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Górecka, H.; Górecki, H. The Effect of Age, Sex, Smoking Habit and Hair Color on the Composition of Hair. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 22, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.H.; Hoffman, R.S. Heavy Metal Chelation in Neurotoxic Exposures. Neurol. Clin. 2011, 29, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer-Holder, M.; Cassill, B.D.; Hayes, S.H. Interrelationships Between Age and Trace Element Concentration in Horse Mane Hair and Whole Blood. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2020, 87, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, D.K.; Goodrich, R.D.; Meiske, J.C. Mineral Concentrations in Hair as Indicators of Mineral Status: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 1982, 54, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunnett, M.; Lees, P. Trace Element, Toxin and Drug Elimination in Hair with Particular Reference to the Horse. Res. Vet. Sci. 2003, 75, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cygan-Szczegielniak, D.; Stanek, M.; Giernatowska, E.; Janicki, B. Impact of Breeding Region and Season on the Content of Some Trace Elements and Heavy Metals in the Hair of Cows. Folia Biol. 2014, 62, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, Z.; Aziz, F. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Dust and Workers’ Scalp Hair as a Bioindicator for Air Pollution from a Steel Factory. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Valko, M. Advances in Metal-Induced Oxidative Stress and Human Disease. Toxicology 2011, 283, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, E.; Fazio, F.; Aragona, F.; Nava, V.; De Caro, S.; Zumbo, A. Toxic Element (As, Cd, Pb and Hg) Biodistribution and Blood Biomarkers in Barbaresca Sheep Raised in Sicily: One Health Preliminary Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 43903–43912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragona, F.; Cicero, N.; Nava, V.; Piccione, G.; Giannetto, C.; Fazio, F. Blood and Hoof Biodistibution of Some Trace Element (Lithium, Copper, Zinc, Strontium and, Lead) in Horse from Two Different Areas of Sicily. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 82, 127378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetto, C.; Fazio, F.; Nava, V.; Arfuso, F.; Piccione, G.; Coelho, C.; Gugliandolo, E.; Licata, P. Data on Multiple Regression Analysis between Boron, Nickel, Arsenic, Antimony, and Biological Substrates in Horses: The Role of Hematological Biomarkers. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e22955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnik, L.T.; Baur, X. The Assessment of Environmental and Occupational Exposure to Hazardous Substances by Biomonitoring. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2009, 106, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetto, M.G.; Caricato, R.; Giordano, M.E. Pollution Biomarkers in Environmental and Human Biomonitoring. Open Biomark. J. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M.; Castaño, A. Non-Invasive Matrices in Human Biomonitoring: A Review. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, F.D.; Babeș, A.C.; Călugăr, A.; Jitea, M.I.; Hoble, A.; Filimon, R.V.; Bunea, A.; Nicolescu, A.; Bunea, C.I. Unravelling Heavy Metal Dynamics in Soil and Honey: A Case Study from Maramureș Region, Romania. Foods 2023, 12, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11464:1994; Soil Quality—Pretreatment of Samples for Physico-Chemical Analyses. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Wahl, L.; Vervuert, I. Commercial Hair Analysis in Horses: A Tool to Assess Mineral Intake? J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2022, 119, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkoong, S.; Hong, S.P.; Kim, M.H.; Park, B.C. Reliability on Intra-Laboratory and Inter-Laboratory Data of Hair Mineral Analysis Comparing with Blood Analysis. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachurska, A.; Walkuska, G.; Cebera, M.; Jaworski, Z.; Chalabis-Mazurek, A. Heavy Metal Status of Polish Konik Horses from Stable-Pasture and Outdoor Maintenance Systems in the Masurian Environment. J. Elem. 2011, 16, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HG 102/2022; Hotărârea Guvernului nr. 102/2022 Privind Calitatea apei potabile. Government of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2022; Directive (EU) 2020/2184; Directive (EU) 2020/2184 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Oztas, T.; Akar, M.; Virkanen, J.; Beier, C.; Goericke-Pesch, S.; Peltoniemi, O.; Kareskoski, M.; Björkman, S. Concentrations of Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) in Blood, Hair and Semen of Stallions in Finland. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2025, 89, 127633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, L.; de Souza, M.V.; Alves Fernandes, R.B.; Ferreira Fontes, M.P.; de Souza Vianna, M.W.; Luz, W.V. Heavy Metals in Horse Blood, Serum, and Feed in Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2006, 26, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Order 756/1997; Soil Quality Guidelines: Threshold Values for Heavy Metal Concentrations in Soil. Ministry of Environment: Bucharest, Romania, 1997.

- Government of Romania. Decision No. 102/2022 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/250414 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32020L2184 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Ministry of Environment and Water Management, Romania. Order No. 161/2006 for the Approval of the Normative Regarding the Classification of Surface Water Quality. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/72005 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Romanian Parliament. Water Law No. 107/1996 (Republished and Amended). Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/g42dmnbq/legea-apelor-nr-107-1996 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2000/60/EC Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32000L0060 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Water Quality for Livestock. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/T0551E/T0551E05.htm (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME). Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for Agricultural Water Use: Livestock. Available online: https://ccme.ca/en/current-activities/canadian-environmental-quality-guidelines (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Horses, 6th Revised Edition. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11653/nutrient-requirements-of-horses-sixth-revised-edition (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Huzum, R.; Gabriel Iancu, O.; Buzgar, N. Geochemical distribution of selected trace elements in vineyard soils from the Husi area. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2012, 7, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, F.D.; Bunea, C.I.; Chira, R.; Bunea, A. Assessment of the Quality of Polluted Areas in Northwest Romania Based on the Content of Elements in Different Organs of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Molecules 2020, 25, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Man, T.; Paulette, L.; Deb, S.; Li, B.; Weindorf, D.C.; Frazier, M. Rapid Assessment of Smelter/Mining Soil Contamination via Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry and Indicator Kriging. Geoderma 2017, 306, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulette, L.; Man, T.; Weindorf, D.C.; Person, T. Rapid Assessment of Soil and Contaminant Variability via Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Copsa Mică, Romania. Geoderma 2015, 243–244, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihali, C.; Dippong, T.; Butean, C.; Goga, F. Heavy metals and as content in soil and in plants in the Baia Mare mining and metallurgical area (NW of Roumania). Rev. Roum. Chim. 2017, 62, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Albulescu, M.; Turuga, L.; Popovici, H.; Masu, S.; Uruioc, S.; Bulz, D. Study regarding the heavy metals content (iron, manganese, copper and zinc) in soil and Vitis vinifera from Caras, -Severin. Annals West Timis, oara. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2009, 18, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, F.D.; Bunea, C.I.; Rusu, T.; Pop, N. Vertical Distribution and Analysis of Micro-, Macroelements and Heavy Metals in the System Soil-Grapevine-Wine in Vineyard from North-West Romania. Chem. Cent. J. 2015, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fechete, F.I.; Popescu, M.; Mârza, S.M.; Olar, L.E.; Papuc, I.; Beteg, F.I.; Purdoiu, R.-C.; Codea, A.R.; Lăcătuș, C.-M.; Matei, I.-R.; et al. Spatial and Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in a Sheep-Based Food System: Implications for Human Health. Toxics 2024, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Codes/Heavy Metals | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | Ni | Co | As | Cr | Hg | Spearman’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone, I encompass the areas of the former tailing’s ponds at Bozânta Mare, Săsar, and Nistru | |||||||||||

| HA-M-TMBTP-O1 | 12.50 ± 1.32 c | 148.47 ± 2.50 e | 4.22 ± 0.14 e | 1.18 ± 0.29 b | 0.57 ± 0.12 b | 0.47 ± 0.03 c | 1.07 ± 0.14 e | 0.82 ± 0.02 bc | BLD | −0.42 | 0.24 |

| HA-T-TMBTP-O1 | 11.83 ± 1.30 c | 139.52 ± 0.90 f | 4.17 ± 0.09 e | 0.81 ± 0.25 d | 0.42 ± 0.10 d | 0.40 ± 0.02 d | 1.89 ± 0.02 a | 0.92 ± 0.01 a | BLD | −0.38 | 0.30 |

| HA-M-RS-O1 | 11.84 ± 3.62 c | 155.22 ± 2.80 e | 5.20 ± 0.09 d | 1.01 ± 0.41 c | 0.50 ± 0.16 c | 0.54 ± 0.02 c | 1.62 ± 0.02 b | 0.88 ± 0.01b | BLD | −0.35 | 0.33 |

| HA-T-RS-O1 | 10.18 ± 0.36 c | 152.25 ± 4.54 e | 5.08 ± 0.07 d | 1.07 ± 0.49 b | 0.53 ± 0.20 b | 0.48 ± 0.02 c | 1.37 ± 0.03 d | 0.96 ± 0.01 a | BLD | −0.37 | 0.31 |

| HA-M-TMN-O1 | 15.08 ± 0.16 b | 170.38 ± 2.05 c | 6.11 ± 0.07 b | 0.91 ± 0.37 d | 0.46 ± 0.15 d | 0.60 ± 0.04 b | 0.74 ± 0.01 g | 0.88 ± 0.01 b | BLD | −0.40 | 0.28 |

| HA-T-TMN-O1 | 13.09 ± 0.33 c | 161.45 ± 0.91 d | 5.92 ± 0.04 b | 0.83 ± 0.17 d | 0.44 ± 0.07 d | 0.60 ± 0.02 b | 0.73 ± 0.03 g | 0.96 ± 0.01 a | BLD | −0.39 | 0.29 |

| Zone, II includes the areas of the former mines: Herja, Ilba, Șuior, Nistru, and UP Central Flotation | |||||||||||

| HA-M-TMH-O1 | 18.91 ± 0.57 a | 186.60 ± 1.29 a | 7.40 ± 0.08 a | 0.94 ± 0.16 c | 0.48 ± 0.06 d | 0.52 ± 0.01 c | 0.60 ± 0.03 g | 0.61 ± 0.01 e | BLD | −0.45 | 0.22 |

| HA-T-TMH-O1 | 16.74 ± 0.42 a | 177.39 ± 0.97 b | 7.22 ± 0.03 a | 0.77 ± 0.12 d | 0.36 ± 0.05 d | 0.67 ± 0.02 a | 1.75 ± 0.04 b | 0.66 ± 0.01 e | BLD | −0.43 | 0.25 |

| HA-M-TMH-O2 | 17.45 ± 0.20 a | 183.65 ± 1.26 a | 7.58 ± 0.07 a | 0.98 ± 0.30 c | 0.49 ± 0.12 d | 0.58 ± 0.07 b | 1.43 ± 0.01 c | 0.56 ± 0.03 f | BLD | −0.41 | 0.27 |

| HA-T-TMH-O2 | 15.24 ± 0.46 b | 171.55 ± 1.01 c | 7.09 ± 0.05 a | 0.88 ± 0.29 d | 0.45 ± 0.12 d | 0.19 ± 0.07 f | 1.57 ± 0.02 c | 0.56 ± 0.01 f | BLD | −0.44 | 0.24 |

| HA-M-CI-O1 | 17.21 ± 1.42 a | 180.05 ± 1.52 a | 6.58 ± 0.07 b | 0.78 ± 0.29 d | 0.35 ± 0.02 e | 0.18 ± 0.05 f | 0.54 ± 0.04 h | 0.91 ± 0.01 a | BLD | −0.46 | 0.21 |

| HA-T-CI-O1 | 15.86 ± 0.13 b | 170.28 ± 0.88 c | 6.42 ± 0.03 b | 1.41 ± 0.09 a | 0.66 ± 0.03 a | 0.13 ± 0.02 g | 1.95 ± 0.02 a | 0.71 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.42 | 0.26 |

| HA-M-CI-O2 | 17.55 ± 0.19 a | 183.59 ± 1.40 a | 6.79 ± 0.03 a | 0.86 ± 0.29 d | 0.45 ± 0.12 d | 0.16 ± 0.05 f | 1.75 ± 0.05 b | 0.75 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.44 | 0.24 |

| HA-T-CI-O2 | 16.65 ± 0.20 b | 175.49 ± 1.20 b | 6.58 ± 0.03 b | 0.85 ± 0.20 d | 0.44 ± 0.08 d | 0.09 ± 0.07 g | 0.80 ± 0.02 f | 0.57 ± 0.01 f | BLD | −0.43 | 0.25 |

| HA-M-CȘ-O1 | 14.81 ± 0.14 b | 166.74 ± 1.63 c | 6.01 ± 0.04 b | 0.90 ± 0.46 c | 0.46 ± 0.18 d | 0.16 ± 0.02 f | 0.77 ± 0.03 g | 1.01 ± 0.01 a | BLD | −0.41 | 0.27 |

| HA-T-CȘ-O1 | 14.05 ± 0.10 b | 159.31 ± 0.91 d | 5.85 ± 0.04 b | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 0.50 ± 0.07 c | 0.13 ± 0.03 g | 0.79 ± 0.04 g | 0.85 ± 0.01 bc | BLD | −0.54 | 0.36 |

| HA-M-CȘ-O2 | 15.71 ± 0.31 b | 117.20 ± 1.28 c | 6.21 ± 0.07 b | 1.07 ± 0.40 b | 0.53 ± 0.16 b | BLD | 0.96 ± 0.03 f | 0.77 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.45 | 0.22 |

| HA-T-CȘ-O2 | 14.66 ± 0.12 b | 163.32 ± 1.03 d | 6.02 ± 0.04 b | 1.37 ± 0.08 b | 0.65 ± 0.03 a | BLD | 1.29 ± 0.04 d | 0.65 ± 0.01 e | BLD | −0.43 | 0.24 |

| HA-M-CȘ-O3 | 16.33 ± 0.09 b | 176.41 ± 0.76 b | 6.41 ± 0.04 b | 1.04 ± 0.42 a | 0.51 ± 0.17 c | 0.13 ± 0.03 g | 1.13 ± 0.01 f | 0.74 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.42 | 0.25 |

| HA-T-CȘ-O3 | 15.57 ± 0.17 b | 169.42 ± 1.05 c | 6.21 ± 0.04 b | 0.69 ± 0.14 d | 0.38 ± 0.06 e | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.01 f | 0.79 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.44 | 0.24 |

| HA-M-TNN-O1 | 15.28 ± 3.52 b | 181.83 ± 1.39 a | 7.19 ± 0.07 a | 0.83 ± 0.06 d | 0.50 ± 0.12 c | BLD | 1.39 ± 0.03 d | 0.82 ± 0.04 bc | BLD | −0.46 | 0.21 |

| HA-T-TNN-O1 | 12.38 ± 0.15 c | 171.57 ± 1.06 c | 6.97 ± 0.04 b | 0.89 ± 0.13 c | 0.46 ± 0.05 d | BLD | 0.62 ± 0.13 g | 0.59 ± 0.01 f | BLD | −0.40 | 0.28 |

| HA-M-UPCFBM-O1 | 14.64 ± 0.10 b | 167.40 ± 1.59 c | 5.85 ± 0.04 b | 0.84 ± 0.40 d | 0.44 ± 0.16 d | BLD | 0.96 ± 0.13 f | 0.63 ± 0.05 e | BLD | −0.41 | 0.27 |

| HA-T-UPCFBM-O1 | 14.25 ± 0.31 b | 158.62 ± 0.96 d | 5.69 ± 0.04 c | 1.15 ± 0.41 a | 0.56 ± 0.16 b | BLD | 1.03 ± 0.01 e | 0.70 ± 0.01 d | BLD | −0.39 | 0.29 |

| Zone III includes the control area | |||||||||||

| HA-M-T-O1-O10 | 1.12 ± 0.07 d | 51.36 ± 1.09 g | 1.49 ± 0.04 f | 0.35 ± 0.13 e | BLD f | 0.04 ±0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 i | 0.12 ± 0.01 g | BLD | −0.64 | 0.07 |

| HA-T-T-O1-O10 | 1.01 ± 0.06 d | 48.56 ± 1.40 g | 1.32 ± 0.04 f | 0.36 ± 0.12 e | 0.16 ± 0.01 f | BLD | 0.08 ± 0.01 i | 0.13 ± 0.01 g | BLD | −0.62 | 0.08 |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Polluted Area vs. Control Area) | 5.33 0.021 | 5.33 0.021 | 5.34 0.023 | 4.57 0.038 | 5.79 0.016 | 1.35 0.245 | 5.78 0.046 | 8.18 0.068 | – | – | – |

| Kruskal–Wallis H p-value (Sample Type (Mane vs. Tail) | 2.14 0.144 | 2.45 0.118 | 0.38 0.538 | 0.053 0.817 | 0.56 0.455 | 0.213 0.642 | 0.38 0.538 | 0.26 0.608 | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r1) p-value (p1) | 0.29 0.147 | −0.028 0.893 | −0.052 0.801 | −0.23 0.254 | −0.21 0.316 | 0.993 - | −0.378 0.057 | −0.103 0.618 | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r2) p-value (p2) | 0.46 0.018 | −0.028 0.893 | 0.206 0.335 | −0.46 0.017 | 0.12 0.562 | 0.996 - | −0.023 0.912 | −0.462 0.017 | – | – | – |

| Spearman’s r (r3) p-value (p3) | −0.09 0.652 | 0.462 0.018 | 0.25 0.650 | −0.046 0.823 | 0.45 0.176 | 0.982 - | −0.032 0.875 | −0.499 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Levels in Horse Mane and Tail Hair, Including Samples from Control Areas | |||||||||||

| Hair specimens harvested from the upper neck (mane) area of horses | |||||||||||

| Wahl et al., 2022 mg/kg FM [44] | 4.19–7.59 | 110–214 | – | – | – | 0.02–0.22 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Namkoong et al., 2013 µg/g [45] | – | – | 0.20–9.25 | 0.03–0.37 | – | – | 0.02–0.62 | – | 0.17–7.89 | – | – |

| Kwiecié et., 2022 mg/kg [11] | 6.10–11.99 | 153.56–185.79 | 0.578–0.813 | 0.011–0.015 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, M.; Tripon, M.A.; Lupșan, A.F.; Bungărdean, D.; Crecan, C.M.; Musteata, M.; Pașca, P.M.; Mârza, S.M.; Purdoiu, R.C.; Papuc, I.; et al. Sentinel Equines in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals and Hematological Biomarkers as Indicators of Environmental Contamination. Toxics 2025, 13, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121064

Popescu M, Tripon MA, Lupșan AF, Bungărdean D, Crecan CM, Musteata M, Pașca PM, Mârza SM, Purdoiu RC, Papuc I, et al. Sentinel Equines in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals and Hematological Biomarkers as Indicators of Environmental Contamination. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121064

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Maria, Mirela Alexandra Tripon, Alexandru Florin Lupșan, Denisa Bungărdean, Cristian Mihăiță Crecan, Mihai Musteata, Paula Maria Pașca, Sorin Marian Mârza, Rober Cristian Purdoiu, Ionel Papuc, and et al. 2025. "Sentinel Equines in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals and Hematological Biomarkers as Indicators of Environmental Contamination" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121064

APA StylePopescu, M., Tripon, M. A., Lupșan, A. F., Bungărdean, D., Crecan, C. M., Musteata, M., Pașca, P. M., Mârza, S. M., Purdoiu, R. C., Papuc, I., Lăcătuș, R., Lăcătuș, C. M., Panait, L. C., Patrichi, T. S., Matei, I.-R., Sisea, C.-R., Bunea, C. I., Călugăr, A., Petrescu-Mag, I. V., ... Bora, F.-D. (2025). Sentinel Equines in Anthropogenic Landscapes: Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals and Hematological Biomarkers as Indicators of Environmental Contamination. Toxics, 13(12), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121064