Valorization of Silicon-Rich Solid Waste into Highly Active Silicate Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Materials

2.2. Batch Adsorption Experiments

2.3. Desorption Experiments of Cd and Pb from Adsorbents

2.4. Material Characterization and Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

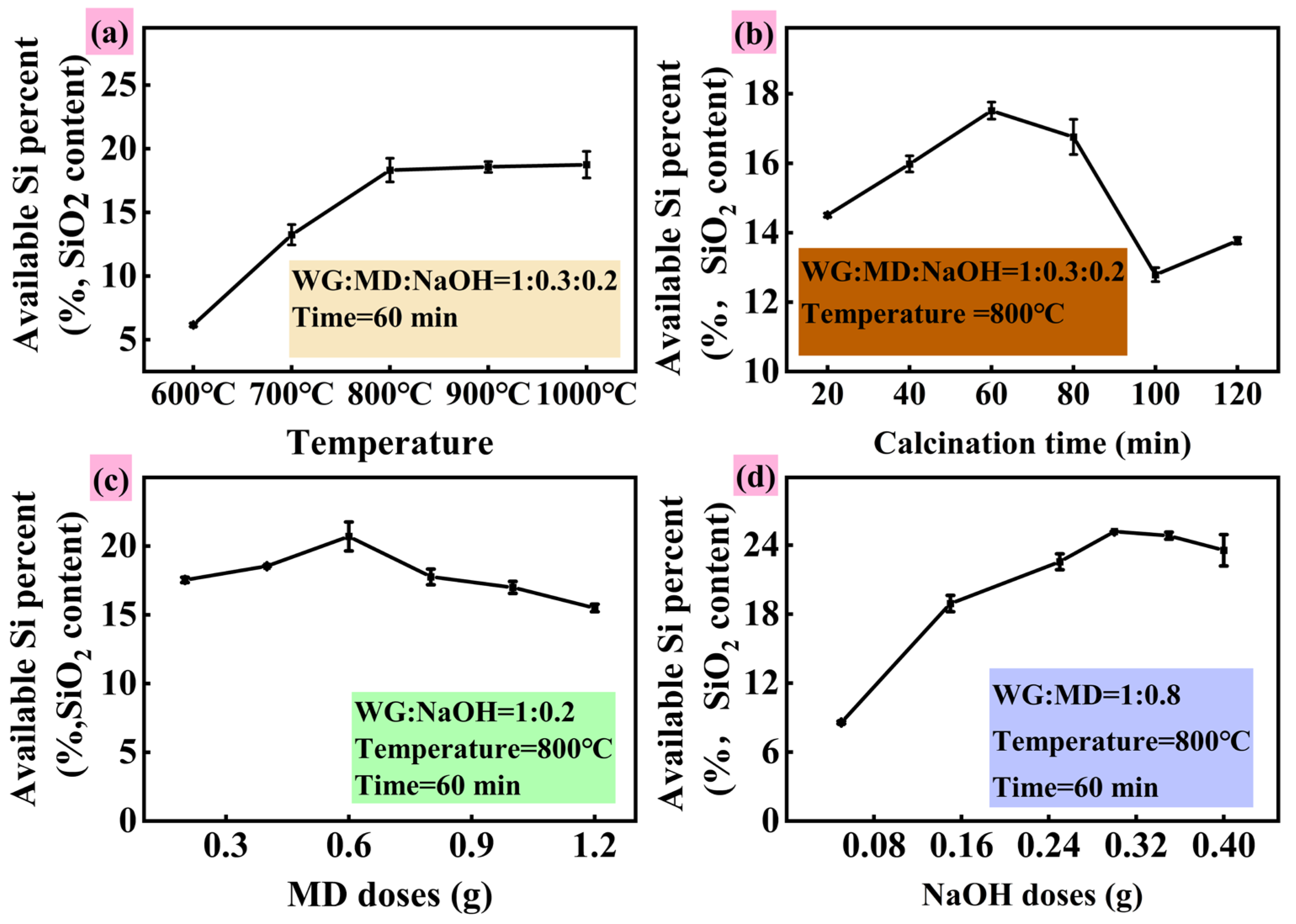

3.1. Preparation of Active Silicon-Based Materials and Conversion of Silicon

3.1.1. Active Silicon and Available Potassium in SSM

| Material | Ingredients | Preparation Parameter | Active Silicon Content (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talcum powder | CaCO3 | 1150 °C—2 h—1:2 | 19.1 | [26] |

| Shendong mining area coal gangue | CaCO3 | 600 °C—1:0.5 | 12.60 | [27] |

| Corn stalk powder | 600 °C—1:0.9 | 14.56 | ||

| CaCO3 + Corn stalk powder | 600 °C—1:0.3:0.9 | 22.97 | ||

| Quartz sand | NaOH | 600 °C—1 h—9:10 | 22.38 | [10] |

| Granite and marble | NaOH | 800 °C—1 h—5/4/1.5 | 26.04% | [1] |

| Leaching residue | Na2CO3 | 700 °C—1 h—0.6:1 | >20% | [15,16] |

| CaCO3 | 800 °C—1 h—0.8:1 | |||

| Recycling of iron ore tailings | KOH | 950 °C—2 h—4:0.4 | 20.77 | [28] |

| Polyaluminum chloride waste residue | - | 1250 °C—1.5 h | 21.0 | [29] |

| Fly ash | KOH | 200 °C—1 h | 34.56% | [13] |

| Biotite acid-leaching residues | K2CO3, Mg(OH)2 | 900 °C—2 h—90:29:69 | Qualified | [30] |

| Mineral phases and microstructure | - | 1250 °C | Potassium extraction ratio (83%) and silicon extraction ratio (96%) | [12] |

| Tobermorite | KOH | 230 °C—15 h (90 rpm), Ca/Si = 0.80 | 14.11% | [31] |

| Smelting slags | CaCO3 | 1000 °C—1 h | CaSiO3, Ca2SiO4 and Ca3SiO5 | [32] |

| Yellow Phosphorus Slag | CaO + MgO | 1450 °C—1 h—1:0.92 | Qualified | [33] |

| coal gangue (CG) | 70%Na2CO3 | 700 °C—2 h—8:2 | 22.63 | [4] |

| Granite and marble (SSM) | NaOH | 600 °C—1 h—1:0.3:0.2 | 24.30 | This study |

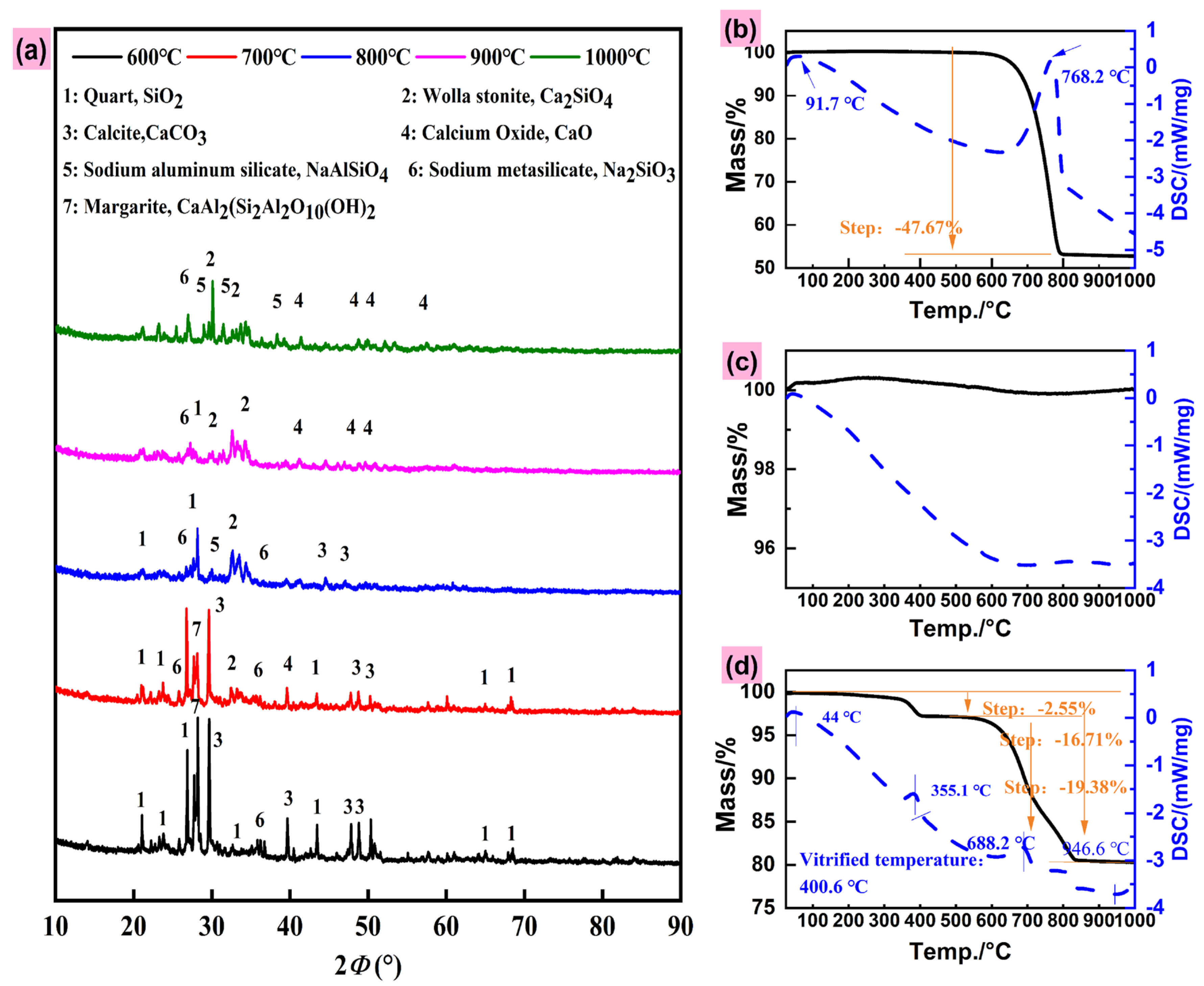

3.1.2. Reaction Behavior During SSM Preparation Process

- (1)

- XRD analysis

- (2)

- TG-DSC analysis

- (3)

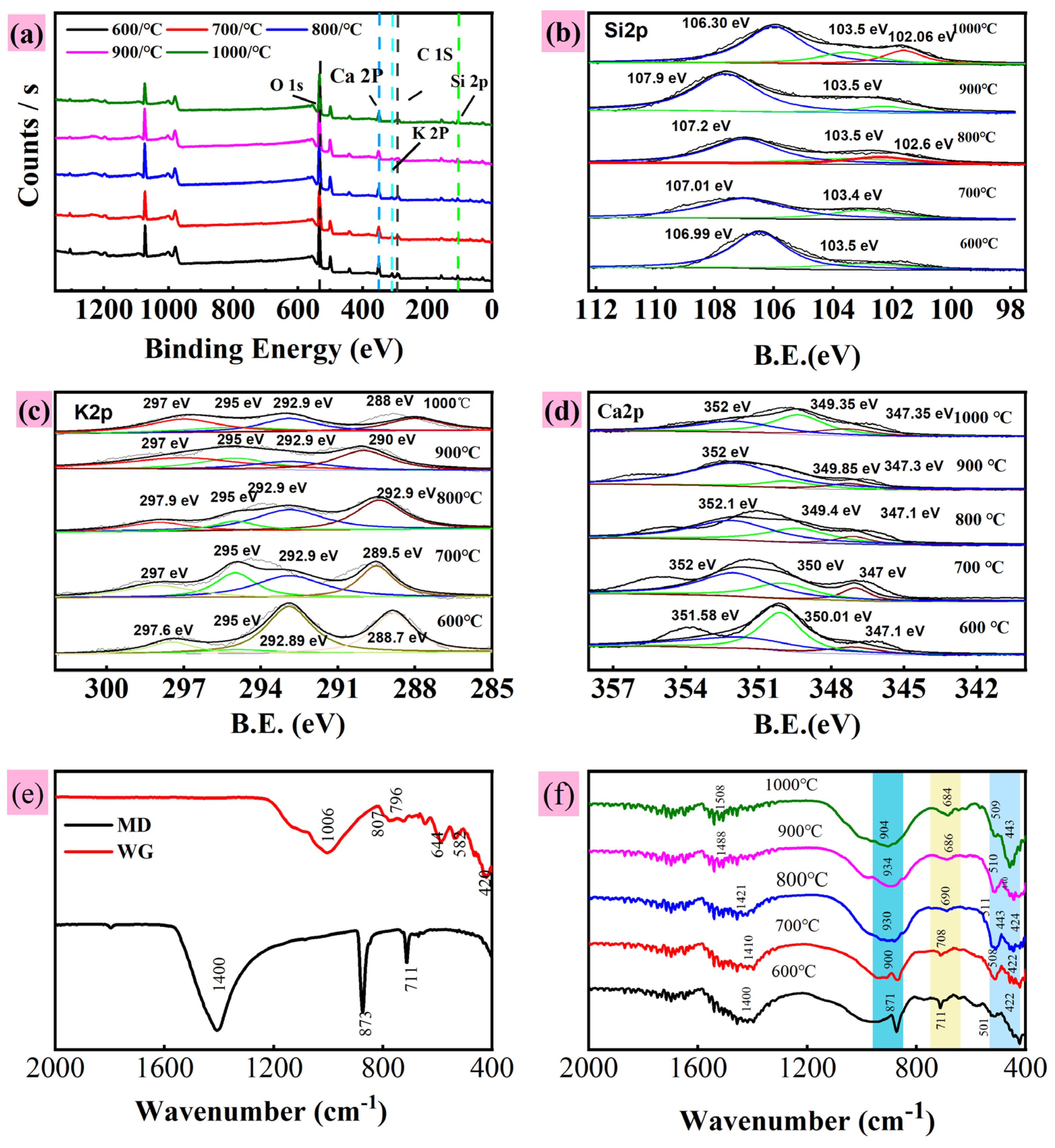

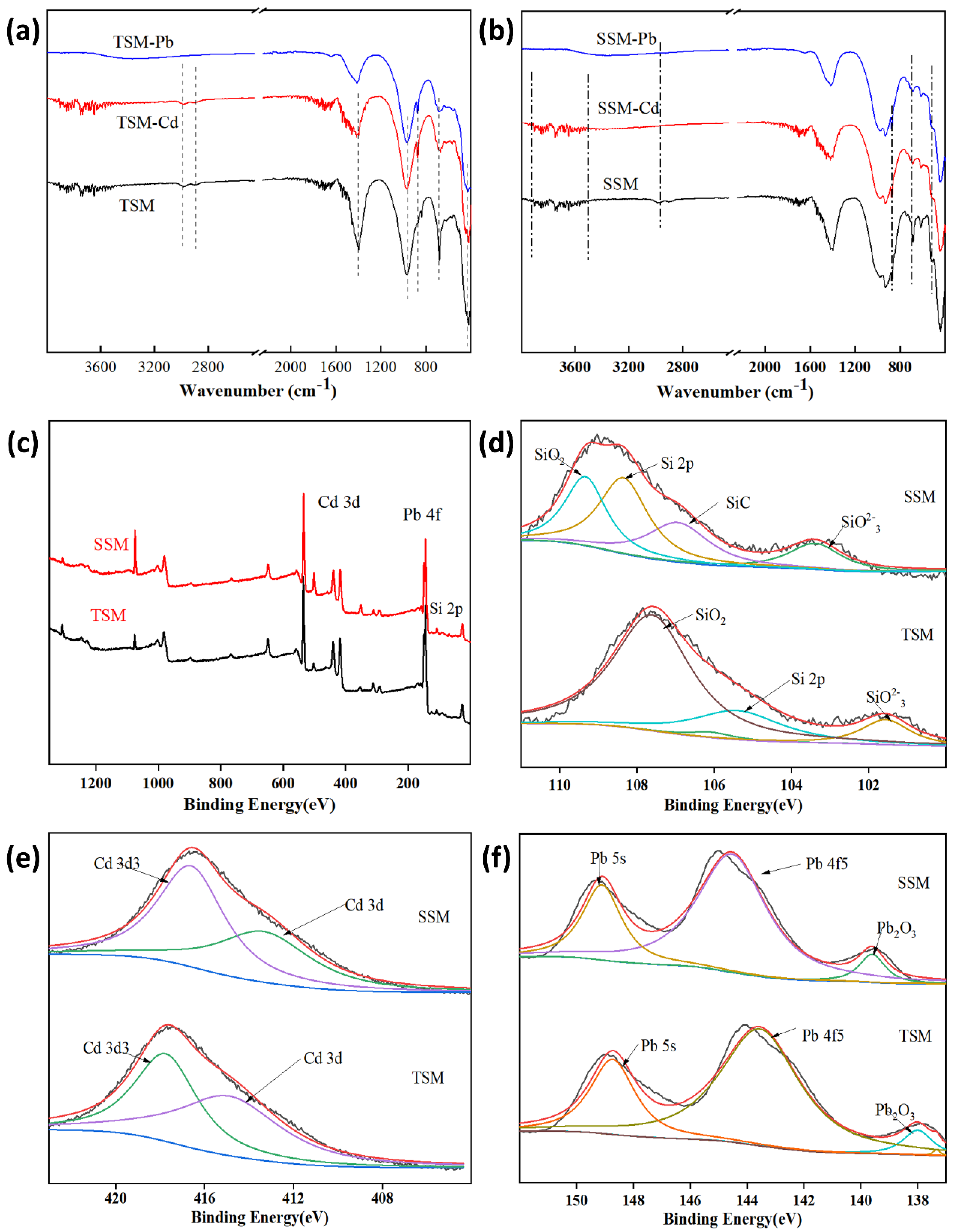

- XPS analysis

- (4)

- FTIR analysis

3.1.3. Mechanism of Active Silicon Formation

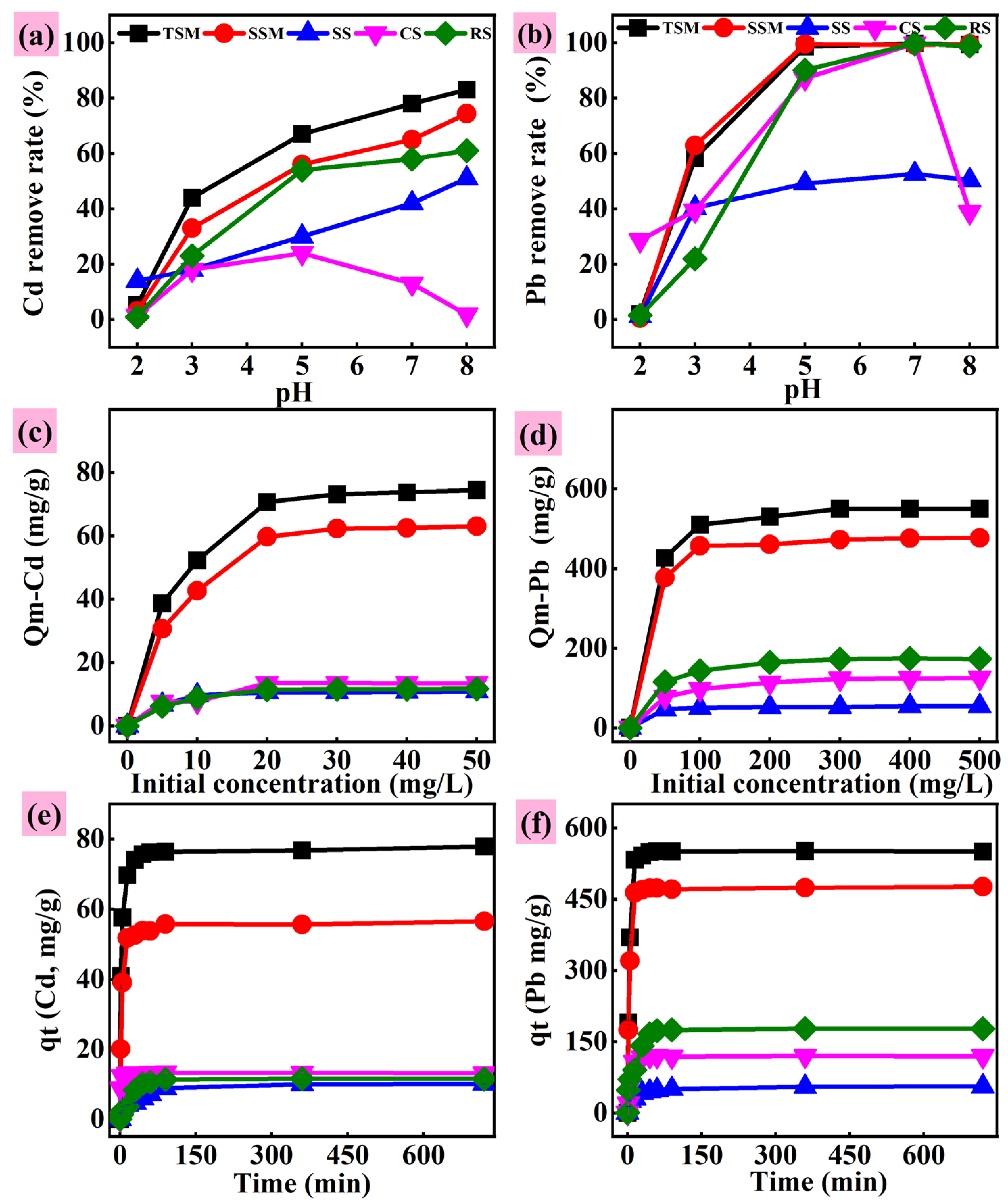

3.2. Adsorption Performance and Mechanism of Active Silicon-Based Materials for Cd and Pb

3.2.1. Effects of Different Factors on Adsorption

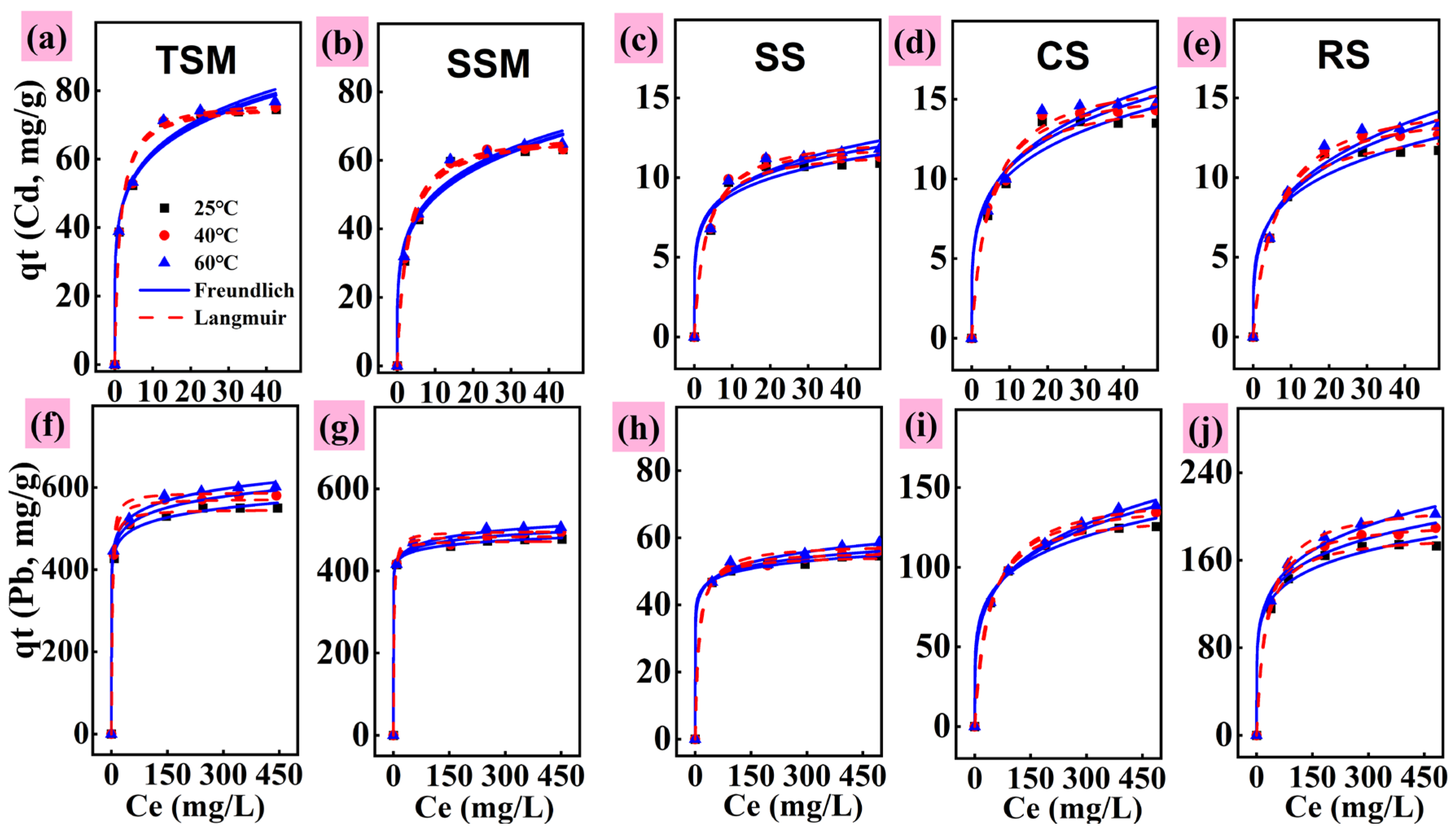

3.2.2. Kinetic and Equilibrium Tests

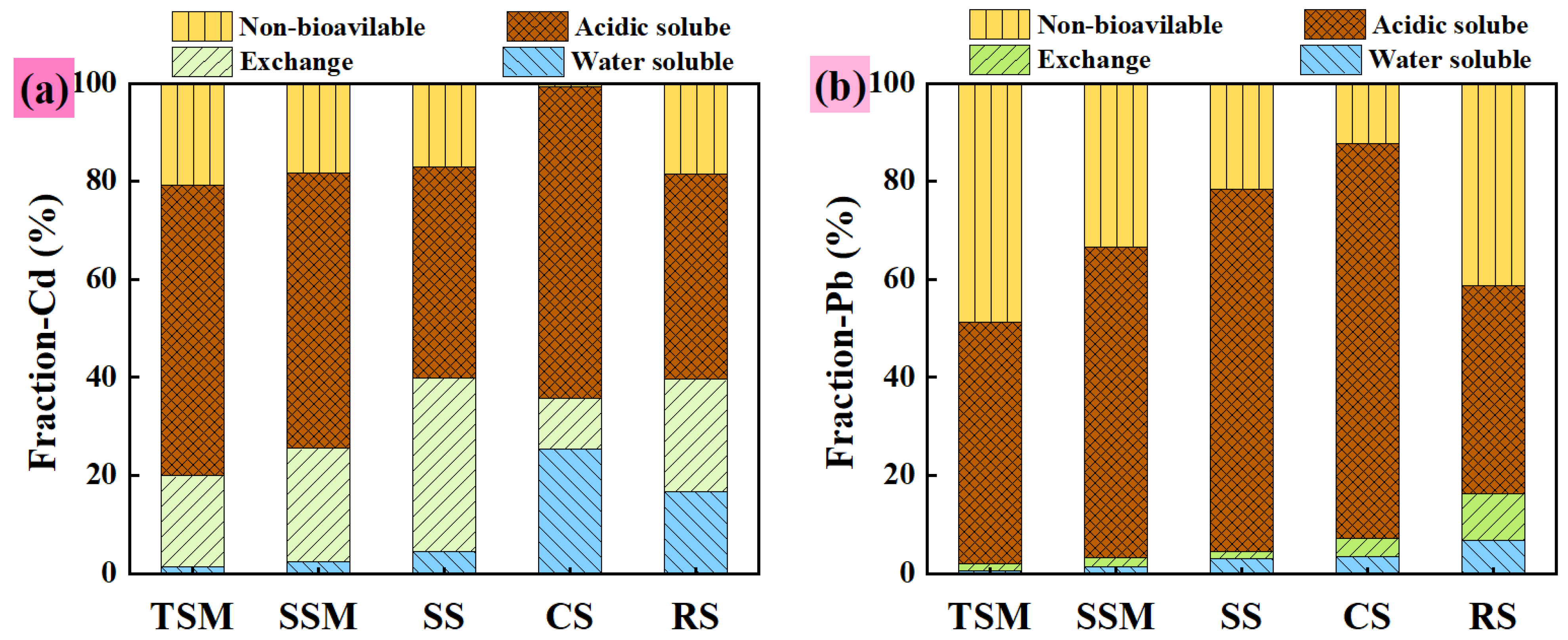

3.2.3. Continuous Desorption Test Analysis

3.2.4. Adsorption Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, T.; Duan, L.X.; Cheng, S.; Jiang, S.J.; Yan, B.B. The preparation of paddy soil amendment using granite and marble waste: Performance and mechanisms. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Yan, B.; Zhao, L.Z.; Chen, T.; Yang, X.F. Effects of active silicon amendment on Pb(II)/Cd(II) adsorption: Performance evaluation and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, P.; Kiventerä, J.; Illikainen, M. Influence of alkali source on properties of alkali activated silicate tailings. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 271, 124932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Jiang, X.L.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.M.; Li, T.G. Sustainable coal gangue—Based silicon fertilizer: Energy—Efficient preparation, performance optimization and conversion mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Chang, J. Adsorption behavior and solidification mechanism of Pb(II) on synthetic C-A-S-H gels with different Ca/Si and Al/Si ratios in high alkaline conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Luo, K.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Ren, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J. Leaching kinetics and dissolution model of steel slag in NaOH solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 434, 136743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.; Gao, L.; Dai, H.; Hong, Z.; Xie, H. An Efficient and Sustainable Approach for Preparing Silicon Fertilizer by Using Crystalline Silica from Ore. JOM J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 2019, 71, 3915–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Chang, N.; He, H.; Zeng, Y.; Qiu, T.; Fang, L. Silicon reduces toxicity and accumulation of arsenic and cadmium in cereal crops: A meta-analysis, mechanism, and perspective study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Choi, J.H. Comparison of interfaces, band alignments, and tunneling currents between crystalline and amorphous silica in Si/SiO2/Si structures. Mater. Res. Express 2022, 9, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, T.; Yan, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Xiao, X. A Functionalized Silicate Adsorbent and Exploration of Its Adsorption Mechanism. Molecules 2020, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Gao, X.; Ueda, S.; Kitamura, S.-Y. Design of a Novel Fertilizer Made from Steelmaking Slag Using the Glassy Phase of the CaO–SiO2–FeO System. Part II: Evaluation of the Novel Fertilizer in a Paddy Soil Environment. J. Sustain. Metall. 2021, 7, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y. Evolution of mineral phases and microstructure of high efficiency Si–Ca–K–Mg fertilizer prepared by water-insoluble K-feldspar. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 94, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, X.; Zhang, T.A.; Lv, G.Z.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Cheng, F.Q.; Guo, Y.X. Sustainable application of coal fly ash: One-step hydrothermal cleaner production of silicon-potassium mineral fertilizer synergistic alumina extraction. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139110. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, P.; Li, G.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Rao, M.; Jiang, T. Extraction and value-added utilization of alumina from coal fly ash via one-step hydrothermal process followed by carbonation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129174. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, B.D.L. Roasted modified lead-zinc tailings using alkali as activator and its mitigation of Cd contaminated: Characteristics and mechanisms. Chemosphere 2022, 297, 134029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Yan, B.; Chen, T.; Xiao, X.-M. Preparation and adsorption characteristics for heavy metals of active silicon adsorbent from leaching residue of lead-zinc tailings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 21233–21242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Song, S.X. Formation mechanism of silica solid solution during reduction roasting of kaolinite and ferric oxide. Chin. J. Nonferr. Met. 2021, 31, 756–764. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, G.; del Bosque, I.F.S.; Frías, M.; de Rojas, M.I.S.; Medina, C. Granite quarry waste as a future eco-efficient supplementary cementitious material (SCM): Scientific and technical considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, F.; McMillan, O.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Qualitative and quantitative characterisation of adsorption mechanisms of lead on four biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Biochar prepared from co-pyrolysis of municipal sewage sludge and tea waste for the adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamic and mechanism. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 220, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zheng, C.; Cui, W.; He, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.C.; He, C. Adsorption of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions on the CS2-modified alkaline lignin. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 319, 123581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nakano, T.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.-L.; He, Y.-J.; Wu, Y.-X.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Tian, W.; Zhou, M.-H.; Wang, S.-X. Studies on adsorption properties of magnetic composite prepared by one-pot method for Cd(II), Pb(II), Hg(II), and As(III): Mechanism and practical application in food. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.T.; Wu, X.P.; Liang, G.P.; Zheng, F.J.; Zhang, M.N.; Li, S.P. A global meta-analysis of the impacts of no-tillage on soil aggregation and aggregate-associated organic carbon. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 5292–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 797-2004; Agricultural Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Silicon Fertiliser. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Li, Q.; Zhong, H.; Cao, Y. Effects of the joint application of phosphate rock, ferric nitrate and plant ash on the immobility of As, Pb and Cd in soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 265, 110576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Chhuon, K.; Wei, Z.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X. Thermal Preparation and Application of a Novel Silicon Fertilizer Using Talc and Calcium Carbonate as Starting Materials. Molecules 2021, 26, 4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, W.X.; Fang, C.J.; Dong, B.B.; Zhang, B. Sustainable and clean utilization of coal gangue: Activation and preparation of silicon fertilizer. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.R.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.K.; Tong, W.S.; Luan, X.L.; Chu, P.K. Preparation and effectiveness of slow–release silicon fertilizer by sintering with iron ore tailings. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.L.; Zhao, F.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Hu, J.Z.; Gao, L.; Li, H.T. Experiment on Production of Silicon Fertilizer from PolyaluminumChloride Industrial Waste Residue, Multipurpose. Util. Miner. Resour. 2022, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Ma, H.G.; Yang, J. Sintering Preparation and Release Properties of K2MgSi3O8 Slow—Release Fertilizer Using Biotite Acid-Leaching Residues as Silicon Source. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 10926–10931. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.F.; Dong, X.S.; Fan, Y.P.; Deng, C.S.; Yang, D.; Chen, R.X.; Chai, W.J. Performance of coal slime-based silicon fertilizer in simulating lead-contaminated soil: Heavy metal solidification and multi-nutrient release characteristics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.Y.; Guo, T.; Liu, X.Y.; Li, R.H.; Du, J.; Zhang, Z.Q. Application of biochar derived from kiwi pruning branches for Cd2+ and Pb2+ adsorption in aqueous solutions. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2019, 38, 1982–1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, C.H.; Li, L.Y.; Hou, L.S.; Liu, B.B.; Gu, S.Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H.B. Sustainable and clean utilization of yellow phosphorus slag (YPS): Activation and preparation of granular rice fertilizer. Materials 2021, 14, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Chen, C.S.; Wang, X.X.; Li, A.M. Extraction of aluminum from coal fly ash by sintering-acid leaching process. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2021, 15, 2389–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Xu, F.; Jiang, H.; Chen, L. Hydroxyapatite modified sludge-based biochar for the adsorption of Cu2+ and Cd2+: Adsorption behavior and mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 321, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Ji, P. Potential of removing Cd(II) and Pb(II) from contaminated water using a newly modified fly ash. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Gao, L.Y.; Wu, R.R.; Wang, H.; Xiao, R.B. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of adsorption mechanisms for Cd (2+) by silicon-rich biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.J. Study on the Adsorption Characteristics and Mechanism of Cadmium in Water by Three Types of Plant-Based Biochar. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangdong, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, J. Preparation of modified palm fiber biochars and their adsorption of Pb2+ in solution. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Hu, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Gao, P.; Ji, P. Optimization of preparation technology for modified coal fly ash and its adsorption properties for Cd2+. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 392, 122461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, J.; Ray, S.K. Chitosan based nano composite adsorbent-Synthesis, characterization and application for adsorption of binary mixtures of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from water. Carbohydr. Polym. Sci. Technol. Asp. Ind. Important Polysacch. 2018, 182, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dian, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, M. Solidification/stabilization of soil heavy metals by alkaline industrial wastes: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 120094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Shah, K.J.; Shi, L.; Chiang, P.C. Removal of Cd(II) and Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions by synthetic mineral adsorbent: Performance and mechanisms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 409, 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, G.C., Jr.; Thatcher, W. Root, Introduction to Chemical Engineering Kinetics and Reactor Design, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, R.I.; El-Eswed, B.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H. Adsorption characteristics of natural zeolites as solid adsorbents for phenol removal from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, mechanism, and thermodynamics studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Song, X.; Tao, L.; Sarkar, B.; Sarmah, A.K.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Novel Fe-Mn binary oxide-biochar as an adsorbent for removing Cd(II) from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 389, 124465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Ahmad, S.; Li, X.; Ri, C.; Tang, J.; Ellam, R.M.; Song, Z. Silicon (Si) modification of biochars from different Si-bearing precursors improves cadmium remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, G.; Tan, X.; Huang, B.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Hua, Q.; Yan, Z. Competitive adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Cu(II) onto chitosan-pyromellitic dianhydride modified biochar. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 506, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Bing, S. Removal characteristics of Cd(II) from acidic aqueous solution by modified steel-making slag. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 246, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Ye, S.; Tian, Y.; Qi, W.; Chen, Y. Preparation of a new sorbent with hydrated lime and blast furnace slag for phosphorus removal from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 166, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Hu, Y. Removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by zeolite synthesized from fly ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 2778–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.K.; Matsuda, M.; Miyake, M. Sorption properties of the activated carbon-zeolite composite prepared from coal fly ash for Ni2+, Cu2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 160, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Kumar, R. Recycled chitosan nanofibril as an effective Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) ionic chelating agent: Adsorption and desorption performance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, B.; Mistry, C.; Shah, A. Seizure modeling of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution by chemically modified sugarcane bagasse fly ash: Isotherms, kinetics, and column study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2193–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Huang, R.; Liu, J.; Shu, Y. Fractionation and release of Cd, Cu, Pb, Mn, and Zn from historically contaminated river sediment in Southern China: Effect of time and pH. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sima, J.; Zhao, L.; Masek, O.; Cao, X. Indispensable role of biochar-inherent mineral constituents in its environmental applications: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhou, M. Adsorption characterization of Cu(II) from aqueous solution onto basic oxygen furnace slag. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 231, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liao, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y. Research progress on synergy technologies of carbon-based fertilizer and its application. Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 10. [Google Scholar]

| Active Silicon-Based Material | First-Order-Model | Second-Order-Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe (mg/g) | K (1/min) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | K (g/(mg·min)) | R2 | ||

| Cd | TSM | 74.5 | 0.3482 | 0.987 | 78.10 | 0.0072 | 0.999 |

| SSM | 54.6 | 0.239 | 0.996 | 57.40 | 0.0062 | 0.989 | |

| SS | 9.87 | 0.025 | 0.933 | 10.50 | 0.0037 | 0.956 | |

| CS | 13.1 | 0.542 | 0.999 | 13.40 | 0.0830 | 0.993 | |

| RS | 11.7 | 0.037 | 0.986 | 12.70 | 0.0042 | 0.959 | |

| Pb | TSM | 548 | 91 | 0.529 | 577 | 5.84 × 10−4 | 0.983 |

| SSM | 472 | 81 | 0.553 | 496 | 7.17 × 10−4 | 0.983 | |

| SS | 50.8 | 0.075 | 0.931 | 54.90 | 0.0021 | 0.980 | |

| CS | 99.9 | 19.21 | 0.463 | 128.10 | 0.0014 | 0.969 | |

| RS | 123 | 24.94 | 0.428 | 176.20 | 4.76 × 10−4 | 0.940 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Miao, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Valorization of Silicon-Rich Solid Waste into Highly Active Silicate Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal. Toxics 2025, 13, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121062

Jiang S, Huang X, Chen H, Miao J, Xiao X, Zhuo Y, Li X, Chen Y. Valorization of Silicon-Rich Solid Waste into Highly Active Silicate Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121062

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Shaojun, Xurong Huang, Huayi Chen, Jiahe Miao, Xinsheng Xiao, Yueying Zhuo, Xiang Li, and Yong Chen. 2025. "Valorization of Silicon-Rich Solid Waste into Highly Active Silicate Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121062

APA StyleJiang, S., Huang, X., Chen, H., Miao, J., Xiao, X., Zhuo, Y., Li, X., & Chen, Y. (2025). Valorization of Silicon-Rich Solid Waste into Highly Active Silicate Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal. Toxics, 13(12), 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121062