Abstract

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a well-established health hazard, yet population-level causal evidence on the long-term effects of its chemical constituents and their interactions with environmental and socioeconomic factors remains scarce. This study leveraged quasi-experimental variation in PM2.5 exposure across Guangdong province, China, during 2007–2018 to evaluate its causal impact on emergency department (ED) visits. We applied a Difference-in-Differences (DID) causal inference framework to obtain counterfactual estimates of long-term exposure effects and complemented this with generalized Weighted Quantile Sum (gWQS) regression to treat PM2.5 as a complex mixture, quantify joint effects, and identify toxic components. The results showed that each interquartile increase in long-term PM2.5 exposure was associated with a 10.2% rise in ED visits, with nitrate (weight = 0.299) and sulfate (0.294) contributing the most strongly, while organic matter exerted greater effects in less-developed regions. Temperature variation further modified these effects, with a 1 °C increase in average summer temperature associated with a 3.3% increase and a decrease in winter temperature linked to a 0.54% increase in constituent-related ED visits. Socioeconomic stratification revealed heterogeneous toxicity profiles across regions. These findings provide robust causal evidence on constituent-specific risks of PM2.5, highlight the utility of integrating causal and mixture methods for complex exposures, and support targeted emission control and climate-adaptive strategies to protect vulnerable populations.

1. Introduction

In 2019, air pollution was estimated to cause approximately 6.7 million premature deaths globally, of which fine particulate matter (PM2.5) accounted for 4.14 million [1]. Since 2019, PM2.5 concentrations in China have continued to decline due to strengthened clean air policies, yet the total health burden attributable to PM2.5 has not shown a consistent reduction because of population aging and the high sensitivity of those with cardiopulmonary diseases to chronic exposure [2,3]. PM2.5 exposure has been linked to various adverse health outcomes, including stroke [4], ischemic heart disease [5], asthma [6], adverse pregnancy outcomes [7], and chronic sinusitis [8], among others [9,10,11]. Despite its recognition as a dominant environmental hazard, several key challenges hinder effective public health interventions [12].

First, most studies emphasize short-term PM2.5 exposure, focusing on mortality or hospitalization risks [13,14]. However, long-term exposures often bear greater public health importance. Emergency department (ED) visits, as a more sensitive indicator of disease burden than hospitalizations or deaths, capture a broader spectrum of health impacts [15], particularly in low- and middle-income countries where emergency care strain remains high. Moreover, emergency department visits encompass a wide range of acute health events, providing a comprehensive reflection of the impact of air pollution on the health of different population groups [16,17]. Annual PM2.5 concentrations reflect year-to-year variations, such as those arising from policy interventions, and prior evidence suggests that even emergency or outpatient visits may be affected by long-term exposure, particularly among chronic or respiratory-sensitive populations [18,19]. Previous studies have also adopted longer temporal exposure windows to investigate the relationship between long-term PM2.5 exposure and emergency department visits [20,21]. In our study, we assume that years with higher annual PM2.5 concentrations are associated with correspondingly higher cumulative counts of emergency department visits, allowing us to examine the impact of long-term exposure at the population level.

Second, research typically treats PM2.5 as a homogeneous mixture, overshadowing compositional heterogeneity. PM2.5 comprises chemically distinct aerosols—including black carbon (BC), organic matter (OM), sulfates, ammonium, and nitrates [22]—which may exert divergent pathophysiological effects. For instance, nitrates can provoke inflammatory responses involving IL-6 [23]; black carbon facilitates pulmonary deposition of toxins and oxidative stress [24,25]; ammonium may modulate immune signaling via Th1/Th2/Th17 pathways [26]; and other components act via distinct mechanisms [27,28]. This underscores the need for regionally tailored interventions, yet current global policies remain largely based on total PM2.5 mass, potentially misallocating limited resources.

Finally, conventional epidemiological models frequently suffer from residual confounding and cannot establish causality, especially when components are intercorrelated [29,30,31]. Mixture analysis is essential to quantify individual and joint component effects in complex exposures.

To directly address these research gaps, this study aims to: (1) quantify the long-term effects of annual PM2.5 exposure on emergency department (ED) visit rates, a sensitive indicator of disease burden; (2) disentangle the heterogeneous health effects of major PM2.5 chemical components—black carbon, organic matter, sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium—within a mixture framework; and (3) examine whether socioeconomic disparities modify these associations. To address these research gaps, we employ a Difference-in-Differences (DID) causal inference framework with a generalized Weighted Quantile Sum (gWQS) regression model. The gWQS model effectively mitigates multicollinearity by combining quantile transformation with mixture dimensionality reduction and has become a widely adopted approach in environmental epidemiology for assessing multi-pollutant exposures [31,32]. This combined approach allows us to disentangle the contributions of individual PM2.5 chemical components and their combined mixture effects while also strengthening causal interpretation by accounting for time-invariant confounders and exposure correlations. Collectively, this framework provides a more robust and policy-relevant understanding of how long-term and compositional variations in PM2.5 influence population-level healthcare demand. We further examine the modifying influences of socioeconomic indicators (per capita GDP, healthcare personnel allocation, urbanization rate) and climatic factors (temperature), advancing epidemiological understanding, refining health risk assessments for susceptible populations, and providing evidence critical for targeted environmental health policy. By identifying the most harmful PM2.5 constituents and their context-specific impacts, our findings can inform regionally tailored emission control strategies, support the integration of climate adaptation into air quality management, and guide resource allocation to reduce health inequalities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings and the Outcome Data

We obtained city-level emergency department visit data from the Guangdong Department of Health [33]. Guangdong is a large and the most populated province in southern China, and it has a population exceeding 126 million as of 2020, accounting for 8.9% of the country’s total population while covering only 1.8% of its land area [34]. In recent decades, Guangdong has faced severe air pollution, accompanied by a rising rate of ED visits [33,35]. We defined the outcome as the annual number of emergency department visits for each city between 2007 and 2018.

2.2. Exposure Data

We obtained daily concentrations of PM2.5 and its components at a 10 km × 10 km spatial resolution for 2007–2018 from the Tracking Air Pollution (TAP) dataset [36]. The TAP dataset integrated ground-based PM2.5 observations, land use data, population data, and other sources to comprehensively estimate the concentrations of PM2.5 and its components [36]. Specifically, TAP defined a high pollution index and employed the SMOTE oversampling technique to balance the sample sizes between high-pollution and normal regions. The SMOTE-oversampled data was then processed using a two-stage random forest model to simulate the concentrations of PM2.5 exposure data. The performance of the model was confirmed with a cross-validation R2 of 0.83 for overall PM2.5 concentrations. The R2 values for its components including BC, OM, nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium with R2 values of 0.64, 0.72, 0.70, 0.75, and 0.75, respectively [37]. The TAP database has been widely utilized in previous studies [38,39], and detailed information about the database has been published elsewhere [36,37]. We calculated the annual average concentrations of PM2.5 and its components for each city by averaging the original values across all grids within the city for each year.

2.3. Confounder Data

We obtained daily mean temperature data from 2007 to 2018 from the China Meteorological Forcing Dataset (CMFD), featuring a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° [40]. To determine the daily mean temperatures for each city, we averaged the temperature values from all grid points within a city. We then calculated the seasonal mean temperatures and their standard deviations (SDs) for summer (from June to August) and winter (from December to February).

We obtained socioeconomic data from the Guangdong Province Statistical Yearbook, which includes information on per capita GDP, urbanization level (proportion of people living in urban areas), and the number of healthcare professionals per thousand people.

2.4. Statistical Method

We employed a Difference-in-Differences (DID) method based on an extension of the Rubin Causal Model to handle confounders across multiple spatial and temporal contexts [41,42]. Confounders are classified into three categories: those associated solely with time, those associated solely with space, and those that vary with both time and space. This approach enhances the traditional DID method by addressing time- and space-specific confounders through comparisons of differences between adjacent years across different regions. Under this approach, the only confounders that need to be controlled are those that vary simultaneously with time and space, such as temperature and GDP per capita. The DID model was specified as:

Model 1

In this model, represents the count of visits to the ED in region s during year t. and are indicator variables for regions and years, respectively. refers to the components of PM2.5, such as sulfate or organic matter. , , , and represent the average temperature and standard deviation during summer and winter, in that order. indicates the GDP per capita of region s in year t. To validate the parallel trend assumption of the DID model [41,42], we observed a minimal correlation between changes in confounding factors and exposure rates following previous studies [42]. As for the link function of the DID model, we chose Poisson regression. The impact of exposure on outcomes was measured by the percentage increase in risk for each IQR increase in exposure level.

We applied the gWQSadd model to explore the combined effects of PM2.5 and its components on the outcome. We combined the gWQS regression with the DID model, using quantile weighting of the independent variables to construct a WQS index, which reduces dimensionality and avoids issues of multicollinearity that traditional methods face when handling exposure [43]. In calculating the WQS index, gWQSadd computes the weight of each variable, reflecting their relative contributions to the WQS index. The gWQSadd model in our study was specified as follows:

Model 2

In this model, represents the quantile of component i, and denotes the weight of the component i. Let b be the number of bootstrap resamples. The index is defined as . Based on previous research, all five components of PM2.5 were designated as risk factors [44]; thus, a positive weight constraint was applied when estimating the weight parameters via bootstrap resampling. In this study, components with values exceeding 0.2 were classified as key components [43].

We also explored the interaction between summer and winter temperature changes and PM2.5 by incorporating interaction terms between summer temperature and the WQS index, as well as between winter temperature and the WQS index, in the gWQSadd model [42].

We used the gWQSint model to investigate whether the effects of PM2.5 vary across different socioeconomic strata [45]. We classified annual GDP per capita, healthcare personnel allocation, and urbanization rate into high and low categories according to their comparison with the mean values. The gWQSint model is as follows:

Model 3

In this model, represents the interaction terms, where each economic indicator variable was separately added to the model. The index is defined as . Typically, the coefficients for the interaction terms between socioeconomic indicators and PM2.5 may not always be positive. Therefore, we use either higher or lower categories as references to fit the model, performing two directional fittings. We use specific-stratum weight (SSW) to represent the relative contribution of each component and reweight it as [31]. reflects the SSW of component i in group j, under a given socioeconomic indicator.

We performed a sensitivity analysis of the results. First, we replaced the main model with the annual moving average concentrations of pollutants for 0–1 and 0–2 years to calculate the lag effects of each component and combined exposure. Second, we used the quintile and decile methods instead of the quartile method used in the main analysis to assess the influence of different categorization strategies on the results. Third, we incorporated a spatial lag term, constructed from the Queen contiguity matrix, into Model 1 to re-estimate the effects of the five PM2.5 components and the WQSadd index, in order to evaluate the potential impact of spatial autocorrelation.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

From 2007 to 2018, a total of 61.536 million ED visits were reported in the study area. During this period, the average concentrations of exposure (PM2.5, nitrates, sulfates, ammonium salts, OM, and BC) were 7.365 (± 2.472) μg/m3, 34.685 (± 11.256) μg/m3, 5.438 (± 1.341) μg/m3, 4.500 (± 1.179) μg/m3, 9.471 (± 2.943) μg/m3, and 2.209 (± 0.786) μg/m3, respectively (Table 1). We observed high correlations among concentrations of the components, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.99 (p < 0.05) (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Analysis of Emergency Department Visits, PM2.5 and Its Components, Temperature, and Socioeconomic Data in Guangdong from 2007 to 2018.

3.2. Causal Associations of PM2.5 and Its Components with Emergency Department Visits

Our study identified a significant correlation between PM2.5 and its components and ED visit rates (p < 0.001). As displayed in Table 2, each IQR increase in PM2.5 concentration may result in a 10.198% (95% CI: 10.171%, 10.225%) increase in the rate of ED visits. Similarly, we observed increases in the rate of ED visits associated with each IQR increase in the concentrations of PM2.5 components: 10.729% (95% CI: 10.698%, 10.761%) for nitrate, 11.415% (95% CI: 11.388%, 11.443%) for sulfate, 10.921% (95% CI: 10.887%, 10.955%) for ammonium, 10.688% (95% CI: 10.661%, 10.716%) for OM, and 11.756% (95% CI: 11.726%, 11.787%) for BC.

Table 2.

The results of the single-component DID (Difference-in-Differences) model.

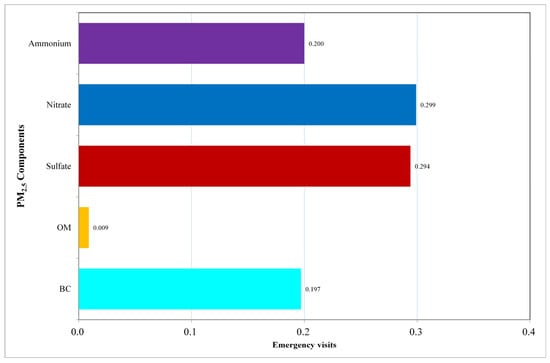

The outcomes of the gWQSadd model are presented in Figure 1. We found that every unit increment in the WQSadd index, which reflects the combined effect of the components mixture, was linked to a 7.56% (95% CI: 7.53%, 7.59%) rise in the rate of ED visits. Among these components, nitrates (weight: 0.299) and sulfates (weight: 0.294) are the most influential, followed by ammonium (weight: 0.2), BC (weight: 0.197), and organic matter (weight: 0.009).

Figure 1.

Contribution of Each Component to the WQSadd Index. This figure presents the contribution weights of the five PM2.5 components—Black Carbon, Organic Matter, Sulfate, Nitrate, and Ammonium—to the Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) Index.

3.3. The Interaction of Temperature and PM2.5 on Emergency Visits

An interaction effect was found between the average temperatures in winter and summer and the combined exposure to PM2.5 (Table 3). At the average winter and summer temperatures across all regions and years, each unit increase in the index corresponds to an IR% of 6.259% (95% CI: 5.918%, 6.601%) in the rate of ED visits. When the summer average temperature rises by 1 °C above the mean, every unit increment in the WQSadd index corresponds to a 3.298% higher IR% of ED visits, resulting in an updated IR% of 9.557% (Pinteraction < 0.001). When the average winter temperature decreases by 1 °C below the average, every unit increment in the WQSadd index may result in a 0.54% greater IR% of ED visits, with an updated IR% of 6.799% and Pinteraction of 0.028.

Table 3.

The mixture effect of PM2.5 components under specific summer and winter temperature conditions.

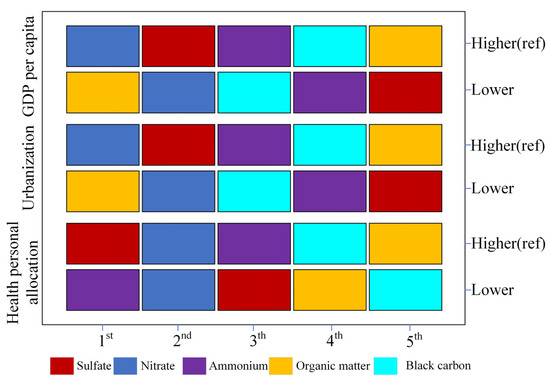

3.4. The Modifying Effects of Socioeconomic Factors

Figure 2 and Figure S2 illustrate the moderating effect of socioeconomic factors on PM2.5. The results across different socioeconomic strata are generally consistent with those observed for the entire population, with nitrates and sulfates playing critical roles in nearly all strata. Specifically, in regions with higher levels of socioeconomic status, nitrates (SSW range: 0.199 to 0.294) and sulfates (SSW range: 0.189 to 0.443) displayed stronger effects. However, in regions with lower GDP (SSW: 0.220) and urbanization rates (SSW: 0.202), organic matter tended to be the most influential among PM2.5 components (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Ranking of Specific Stratified Weights (SSWs) for PM2.5 Components. This figure illustrates the ranking of specific stratified weights (SSWs) for PM2.5 components under different socioeconomic levels (including health personal allocation, urbanization, and GDP per capita).

In sensitivity analysis, despite some variations in effect sizes (IR%) when using 1–2 year lagged data or applying quintiles and deciles instead of quartiles, or incorporating a spatial lag term constructed from the Queen contiguity matrix into Model 1 to account for potential spatial autocorrelation, our findings remain unchanged (Table S3).

4. Discussion

Our study revealed a significant positive association between PM2.5, its components, and emergency department visits, with a particular emphasis on the substantial contribution of sulfate. Additionally, our subgroup analysis revealed significant effects of nitrate and sulfate across nearly all strata, followed by ammonium. In regions with lower socioeconomic status, the correlations were more pronounced for organic matters than other components. This study also explored the interaction between temperature and the PM2.5 mixture, suggesting that both increases in average summer temperatures and decreases in average winter temperatures may exacerbate the impact of the PM2.5 mixture.

Because PM2.5 components were highly correlated (r = 0.86–0.99), the single-component DID models exhibited large variance inflation factors (VIF > 10), indicating potential multicollinearity and unstable estimates (Table S4). To address this issue, we employed DID-based gWQS regression in a complementary manner to single-component DID models. The gWQS approach transforms exposures into quartiles and applies bootstrap weighting to mitigate collinearity while simultaneously quantifying the overall mixture effect and the relative contribution of each component, thereby complementing the straightforward interpretation provided by single-component analyses.

We observed that nitrate and sulfate are the components most closely associated with increased emergency department visits. Previous studies have also reached similar conclusions, which suggested significant associations of nitrate and sulfate with a variety of diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases [46], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [47], asthma [48], and others [49]. For instance, a study in California found that nitrate and sulfate in PM2.5 contributed to increased IR% of respiratory diseases such as asthma (IR%: 3.3%, 95% CI: 1.1%,5.5%) and bronchitis (IR%:3.0%, 95% CI: 0.4%,5.7%) [50]. Experimental studies suggested that nitrate and sulfate in PM2.5 particles could penetrate the pulmonary surfactant barrier and interfere with gene expression in lung cells [28], leading to neutrophil infiltration in the lungs which further impairs respiratory function [51]. Nitrate and sulfate could also penetrate the placenta barrier and result in various adverse pregnancy outcomes [52] which is also a significant part of emergency department visits. Compared with these findings from the gWQS model, the results from the DID model were different, which showed a significant health impact of black carbon (BC) rather than nitrate. This disparity was commonly reported in previous studies [53,54]. The use of the gWQS model, as a mixture analysis method, enables the investigation of the joint effects of PM2.5 component mixtures. This model addresses the limitations of single-component DID models, which can only consider one component at a time and cannot account for the high correlations among components. However, evidence regarding the mechanisms through which different components affect health remains scarce, necessitating further research to elucidate their underlying pathways.

was also identified as having significant health effects in the current research. Research has demonstrated that is linked to various diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (ILD) (HR per decile increase: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.36, 1.40), asthma (OR per standard deviation increase: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.41), and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (OR per standard deviation increase:1.21, 95% CI: 1.10,1.32) [48,53,54]. The potential mechanisms underlying the health impact of ammonium salts include inducing systemic inflammation, disrupting the balance between regulatory T cells and TH1 cells, activating the NF-κB pathway to trigger respiratory inflammation, and may activate mast cells and basophils, potentially playing a key role in asthma [26,55]. In the Pearl River Delta region, non-agricultural sources account for 63.74% of ammonium salts. The main contributors include biomass burning (12.71% ± 3.63%), coal combustion (14.70% ± 5.38%), vehicle emissions (14.24% ± 5.55%), and waste (22.09% ± 12.48%) [56]. Therefore, the existing environmental policies should be expanded to cover these sources to effectively reduce the disease burden.

Our study found that organic matter had the most significant health effects among the five components in regions with lower socioeconomic status. This result aligns with findings from previous studies. For instance, Cai et al. reported that organic matter had a particularly strong impact on stroke outcomes in regions with relatively lower economic development, with an interquartile range increase of 3.47 μg/m3 in organic matter associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.086 (95% CI: 1.069–1.104) for stroke fatality among 3,069,093 hospitalized patients [57]. This finding may be attributed to differences in multiple aspects such as pollution sources and medical services across regions [58,59,60]. In economically disadvantaged regions, a substantial proportion of households continue to rely on traditional solid fuels such as wood, coal, and crop residues like straw for cooking and heating [61,62]. The incomplete combustion of these organic materials not only produces elevated levels of particulate matter but also generates a complex mixture of organic pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and other toxic by-products, which can lead to significant health hazards [63,64,65,66]. Some studies suggest that the use of biomass fuels in low-income regions generates significant amounts of PM2.5 [62,67]. A study in Chicago found that low-income households had significantly higher indoor PM2.5 levels compared with high-income households (52.5 μg/m3 vs. 18.2 μg/m3), indicating that economically disadvantaged households are exposed to elevated indoor air pollution. This suggests that in lower-SES regions, indoor sources may amplify the health effects of PM2.5 organic matter and increase the risk of emergency department visits [68]. Due to the lack of effective management and residents’ tendency to spend more time indoors, exposure levels are higher, thereby increasing the risk of disease burden [69,70,71,72]. Insufficient sanitation facilities, lack of health awareness and medical services, and poor management of chronic diseases in these regions may also contribute to a higher rate of ED visits [73,74,75]. Socioeconomic position (SEP) not only influences overall health but may also play a role in disease and mortality related to air pollution. Low-income or disadvantaged populations are often exposed to higher levels of air pollution and may be more susceptible due to interactions with other harmful exposures or chronic health conditions [76,77]. Therefore, it is crucial to further investigate the impacts of PM2.5 on health across various socioeconomic levels. Though the mechanisms remain incompletely understood, controlling the combustion of organic matter and adopting cleaner energy sources, such as natural gas and clean coal, could improve the health of residents in economically challenged areas.

Our study shows that temperature affects the effects of PM2.5 on health, with an increase in summer average temperatures and a decrease in winter average temperatures both leading to higher emergency department visit rates. Research by Yitshak-Sade et al. found that fluctuations in temperature and the increase in extreme weather events could interact with air pollutants, posing risks to human health [78]. Studies on PM2.5 and asthma have shown that within a temperature range of 1.1–44.4 °F, each 1 μg/m3 rise in PM2.5 concentration was linked to a 7.9% increase in the incidence of asthma; in the 44.5–58.6 °F range, it was 6.9%; in the 58.7–70.1 °F range, 2.9%; and in the 70.2–80.5 °F range, 7.3% [79]. A study in Guangzhou found that under low- and high-temperature conditions, each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentration led to a 0.73% and 0.46% rise in non-accidental mortality rates, respectively [80]. Higher temperatures and humidity levels in the summer can make the population more sensitive to the health burden caused by PM2.5 [81,82], probably by exacerbating the oxidative stress and inflammatory responses induced by the particles [83]. Higher temperatures may also enhance atmospheric photochemical reactions, promoting the formation of secondary aerosols such as nitrates and sulfates, thereby increasing the health burden [84]. The decrease in winter temperature enhances the body’s response to air pollutants [85]. The low temperature further promotes the reaction between and OH radicals, leading to the formation of [86]. Additionally, the drop in winter temperatures can weaken immune function [87]. A large body of research has shown that PM2.5 exposure not only leads to increased arterial blood pressure but is also associated with elevated levels of C-reactive protein, which in turn exacerbates the disease burden [88,89]. Our findings align with numerous previous studies; however, the interactions between PM2.5 and temperature exhibit variability across different regions. The mechanisms underlying this interaction need further investigation. A study found that both heat waves and cold spells can modify the health effects of PM2.5 constituents on stroke mortality. Heat waves exhibited pronounced synergistic interactions with secondary inorganic aerosols (NO3−, SO42−, NH4+), substantially increasing the risk of stroke death, whereas the interactions during cold spells were weaker, with risk estimates ranging from 1.19 to 1.55 for heat waves and 1.03–1.11 for cold spells [90].

Our findings indicate that the PM2.5 components most strongly associated with adverse health impacts—particularly nitrate and sulfate—are mainly linked to traffic and industrial emissions, while organic matter poses greater risks in less economically developed regions. These results underscore the need for source-oriented emission control strategies to reduce long-term exposure risks. Consistently, recent policy simulations in Guang-dong demonstrate that structural interventions—including industrial upgrading, strict-er vehicle emission standards, and cleaner energy transitions—are more effective in reducing harmful PM2.5 components than end-of-pipe controls alone [91]. To further mitigate exposure and its associated health burden, current environmental policies should be expanded to incorporate green infrastructure, such as urban street trees and vegetation barriers, which have been shown to reduce traffic-related pollution [92,93]. Moreover, policy evaluations in Guangdong highlight that socioeconomic and institutional conditions critically shape PM2.5 emission patterns. Increasing marketisation and advancing industrial transformation can curb pollution from traditional manufacturing, while globalization-driven clean technology adoption and stringent environmental regulation effectively reduce emissions from pollution-intensive industries [94]. Conversely, decentralization without adequate regulatory oversight may exacerbate industrial pollutant discharge, reinforcing the importance of coordinated cross-city governance to address spatial spillover effects within the Pearl River Delta [95]. Together, these insights support multi-dimensional strategies that integrate economic restructuring, regulatory enhancement, and green urban development to reduce harmful PM2.5 components and their health impacts. Our study found that organic matter in PM2.5 has the greatest impact on ED visits in less economically developed regions. This aligns with evidence from rural China, where household use of solid fuels such as wood and crop residues generates high levels of indoor organic particles, particularly in kitchens and bedrooms, posing greater health risks for residents who spend more time indoors, such as elderly women [96]. Therefore, in addition to controlling traffic and industrial emissions, promoting cleaner household energy and improving indoor air quality are crucial strategies to reduce the health burden of PM2.5 in economically disadvantaged areas.

Our study boasts several strengths, including the combination of the causal inference and the mixture analysis approaches, and being among the few studies elucidating the causal links between PM2.5 components mixture and the rate of emergency department visits. However, we still need to interpret our findings cautiously. Firstly, the absence of detailed individual-level data restricts the capacity to control for individual-level confounders. Secondly, due to the absence of high-resolution PM2.5 and component data, we relied on simulated TAP data at 10 × 10 km resolution, which may overlook within-city exposure differences. Due to the limited spatial resolution of TAP exposure data, some exposure misclassification is inevitable; however, this is expected to be non-differential across cities, likely biasing the results toward the null rather than generating spurious associations [97]. While these data have been rigorously validated against ground-based measurements, caution is still needed when interpreting the results. While our findings contribute important evidence from Guangdong, further studies conducted in regions with more diverse environmental and sociodemographic characteristics are needed to evaluate the generalizability and robustness of PM2.5 component–health associations. Finally, we used the DID model to explore causal effects, but the validity of this approach relies on the parallel trend assumption which could not be directly tested in this multi-year and multi-area design. Following the framework of previous studies, we assessed this assumption by examining low correlation of PM2.5 components with potential confounders (Table S1). Despite these limitations, we identified a significant correlation of PM2.5 and its components with ED visits.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that long-term PM2.5 exposure, particularly its nitrate and sulfate components, was strongly associated with increased emergency department visits. We also found that climatic and socioeconomic factors modified these associations, with higher risks under extreme temperatures and greater contributions of organic matter in less-developed regions. These findings provide causal evidence of constituent-specific health risks, highlight the vulnerability of disadvantaged populations, and underscore the need for targeted emission reductions in nitrate and sulfate, alongside clean energy promotion in rural and underdeveloped areas. Integrating air quality management with climate adaptation strategies will be critical to reducing the health burden of PM2.5.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/toxics13110973/s1, Table S1: Correlation Analysis Between the Relative Rate Differences of PM2.5 Components Concentrations and Those of the Confounders. Table S2: Specific Stratified Weights of PM2.5 Components Across Different Socioeconomic Status Levels. Table S3: Results of Sensitivity Analysis. Table S4: Variance inflation factor (VIF) for multi-exposure DID model. Figure S1: Mean concentration of PM2.5 and mean proportion of 5 PM2.5 constituents in Guangdong, China, 2007–2018. Figure S2: Pearson Correlation Coefficient Matrix Among the Five PM2.5 Components (including organic matter (OM), black carbon (BC), sulfate (SO42−), nitrate (NO3−), and ammonium (NH4+)). Figure S3: Ranking of Specific Stratified Weights (SSWs) for PM2.5 Components (direction 2).

Author Contributions

P.Z.: Writing—original draft, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization. C.X.: Visualization, Validation, Writing—original draft. S.W.: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. S.L. (Shao Lin): Supervision, Validation. G.D.: Supervision, Resources. J.L.: Data curation, Visualization. S.Y.: Data curation, Visualization. T.Z.: Visualization, Validation. X.Y.: Visualization, Validation. X.L.: Data curation, Visualization. S.L. (Sizhe Li): Data curation, Visualization. X.W.: Data curation, Visualization. J.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization. W.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82204162), Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by China Association for Science and Technology (2023QNRC001), Guangdong Provincial Pearl River Talents Program (0920220207), Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515010823), and Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (2023A04J2072, 2024A04J4485).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- HEI The Health Effects Institute. Health Impacts of PM2.5. Fine-Particle Outdoor Air Pollution Is the Largest Driver of Air Pollution’s Burden of Disease Worldwide. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/health/pm (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Xu, F.; Huang, Q.; Yue, H.; Feng, X.; Xu, H.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bryan, B.A. The Challenge of Population Aging for Mitigating Deaths from PM2.5 Air Pollution in China. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Brandt, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Ye, Z.; Chen, T.; Dong, S.; Geels, C.; Yuan, Y.; Nenes, A.; Im, U. The Recent and Future PM2.5-Related Health Burden in China Apportioned by Emission Source. npj Clean. Air 2025, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Q.; He, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Cai, L.; Cao, S. Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 and Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexeeff, S.E.; Liao, N.S.; Liu, X.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Sidney, S. Long-Term PM2.5 Exposure and Risks of Ischemic Heart Disease and Stroke Events: Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e016890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, C.; Yost, M.; Sampson, P.; Arias, G.; Torres, E.; Vasquez, V.B.; Bhatti, P.; Karr, C. Regional PM2.5 and Asthma Morbidity in an Agricultural Community: A Panel Study. Environ. Res. 2015, 136, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Fu, H.; Yu, S.; Zhou, M.; Guo, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, A.; Zhao, M.; et al. PM2.5 Leads to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes by Inducing Trophoblast Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Apoptosis via KLF9/CYP1A1 Transcriptional Axis. eLife 2023, 12, e85944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, L.J.; Schwarzbach, H.L.; Moore, J.A.; Boudreau, R.M.; Willson, T.J.; Lee, S.E. Air Pollutants May Be Environmental Risk Factors in Chronic Rhinosinusitis Disease Progression. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Chang, L.; Guo, C.; Lin, C.; Lau, A.K.H.; Tam, T.; Lao, X.Q. Reduced Ambient PM2.5, Better Lung Function, and Decreased Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Lin, F.C.-F.; Wu, M.-F.; Nfor, O.N.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Lung, C.-C.; Ho, C.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Liaw, Y.-P. Association between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and PM2.5 in Taiwanese Nonsmokers. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Mao, F. Short-Term Effects of Ambient PM1 and PM2.5 Air Pollution on Hospital Admission for Respiratory Diseases: Case-Crossover Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 224, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winquist, A.; Klein, M.; Tolbert, P.; Flanders, W.; Hess, J.; Sarnat, S. Comparison of Emergency Department and Hospital Admissions Data for Air Pollution Time-Series Studies. Environ. Health 2012, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, S.E.; Wyatt, L.H.; Wei, L.; Paul, N.; Serre, M.L.; West, J.J.; Henderson, S.B.; Rappold, A.G. Short-Term Exposure to Wildfire Smoke and PM2.5 and Cognitive Performance in a Brain-Training Game: A Longitudinal Study of U.S. Adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 067005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.S.V.; Lee, K.K.; McAllister, D.A.; Hunter, A.; Nair, H.; Whiteley, W.; Langrish, J.P.; Newby, D.E.; Mills, N.L. Short Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.J.; Wier, L.M.; Stocks, C.; Blanchard, J. Overview of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2011. In Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, A.; Bell, M.L.; Al-Aly, Z.; Ahn, S.; Kim, S.; Kwon, D.; Kang, C.; Oh, J.; Kim, H.; et al. PM2.5 and Hospitalizations through the Emergency Department in People with Disabilities: A Nationwide Case-Crossover Study in South Korea. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2024, 53, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyton, A.; Baer, R.J.; Benmarhnia, T.; Bandoli, G. Exposure to Air Pollution and Emergency Department Visits During the First Year of Life Among Preterm and Full-Term Infants. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, V.C.; Kazemiparkouhi, F.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Long-Term PM2.5 Exposure and Respiratory, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality in Older US Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexeeff, S.E.; Deosaransingh, K.; Van Den Eeden, S.; Schwartz, J.; Liao, N.S.; Sidney, S. Association of Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution With Cardiovascular Events in California. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Marcon, A.; Bertelsen, R.J.; Benediktsdottir, B.; Brandt, J.; Frohn, L.M.; Geels, C.; Gislason, T.; Heinrich, J.; Holm, M.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Greenness in Association with Respiratory Emergency Room Visits and Hospitalizations: The Life-GAP Project. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 120938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambliss, S.E.; Matsui, E.C.; Zárate, R.A.; Zigler, C.M. The Role of Neighborhood Air Pollution in Disparate Racial and Ethnic Asthma Acute Care Use. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateraki, S.; Asimakopoulos, D.N.; Maggos, T.; Assimakopoulos, V.D.; Bougiatioti, A.; Bairachtari, K.; Vasilakos, C.; Mihalopoulos, N. Chemical Characterization, Sources and Potential Health Risk of PM2.5 and PM1 Pollution across the Greater Athens Area. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-C.; Chuang, H.-C.; Ward, T.J.; Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.; Cao, J.; Hsiao, T.-C.; Ho, K.-F. Toxicological Effects of Personal Exposure to Fine Particles in Adult Residents of Hong Kong. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.C.; Arden Pope, I.I.I.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassee, F.R.; Héroux, M.-E.; Gerlofs-Nijland, M.E.; Kelly, F.J. Particulate Matter beyond Mass: Recent Health Evidence on the Role of Fractions, Chemical Constituents and Sources of Emission. Inhal. Toxicol. 2013, 25, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, M. Ammonia Induces Treg/Th1 Imbalance with Triggered NF-κB Pathway Leading to Chicken Respiratory Inflammation Response. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; da Silva, E.; Hou, L.; Denslow, N.D.; Xiang, P.; Ma, L.Q. Human Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Metabolomics Perspective. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ku, J.; Lee, S.-M.; Hwang, H.; Lee, N.; Kim, H.; Yoon, K.-J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.Q. Potential Toxicity of Inorganic Ions in Particulate Matter: Ion Permeation in Lung and Disruption of Cell Metabolism. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.L.; Dominici, F.; Ebisu, K.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M. Spatial and Temporal Variation in PM2.5 Chemical Composition in the United States for Health Effects Studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamra, G.B.; Buckley, J.P. Environmental Exposure Mixtures: Questions and Methods to Address Them. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2018, 5, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Du, Z.; Wu, W.; Ju, X.; Yimaer, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. The Causal Links between Long-Term Exposure to Major PM2.5 Components and the Burden of Tuberculosis in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wei, Y.; Amini, H.; Wang, C.; Weisskopf, M.; Koutrakis, P.; Schwartz, J. Fine Particle Components and Risk of Psychiatric Hospitalization in the U.S. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 849, 157934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCGP. Guangdong Health Statistical Yearbook; Health Commission of Guangdong Province: Guangzhou, China, 2022.

- SBGP. Guangdong Statistical Yearbook; Statistics Bureau of Guangdong Province: Guangzhou, China, 2022.

- Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Wu, G.; Du, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Hao, Y. Relationships between Long-Term Exposure to Major PM2.5 Constituents and Outpatient Visits and Hospitalizations in Guangdong, China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, G.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, T.; Tong, D.; Zheng, B.; Peng, Y.; et al. Tracking Air Pollution in China: Near Real-Time PM2.5 Retrievals from Multisource Data Fusion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12106–12115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, D.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; He, K. Chemical Composition of Ambient PM2.5 over China and Relationship to Precursor Emissions during 2005–2012. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 9187–9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Xing, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Ding, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Duan, L.; Hao, J. Progress of Air Pollution Control in China and Its Challenges and Opportunities in the Ecological Civilization Era. Engineering 2020, 6, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Hu, J.; Qin, M.; Guo, S.; Hu, M.; Wang, H.; Lou, S.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; et al. Modeling Particulate Nitrate in China: Current Findings and Future Directions. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; He, J.; Tang, W.; Lu, H.; Qin, J. China Meteorological Forcing Dataset (1979–2018); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Practical Implications of Modes of Statistical Inference for Causal Effects and the Critical Role of the Assignment Mechanism. Biometrics 1991, 47, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kloog, I.; Coull, B.A.; Kosheleva, A.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.D. Estimating Causal Effects of Long-Term PM2.5 Exposure on Mortality in New Jersey. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, C.; Gennings, C.; Wheeler, D.C.; Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of Weighted Quantile Sum Regression for Highly Correlated Data in a Risk Analysis Setting. JABES 2015, 20, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, T. A Component-Specific Exposure–Mortality Model for Ambient PM2.5 in China: Findings from Nationwide Epidemiology Based on Outputs from a Chemical Transport Model. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 226, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Rahbar, M.H.; Samms-Vaughan, M.; Bressler, J.; Bach, M.A.; Hessabi, M.; Grove, M.L.; Shakespeare-Pellington, S.; Coore Desai, C.; Reece, J.-A.; et al. A Generalized Weighted Quantile Sum Approach for Analyzing Correlated Data in the Presence of Interactions. Biom. J. 2019, 61, 934–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, V.C.; Yu, I.T.-S.; Qiu, H.; Ho, K.-F.; Sun, Z.; Louie, P.K.K.; Wong, T.W.; Tian, L. Short-Term Associations of Cause-Specific Emergency Hospitalizations and Particulate Matter Chemical Components in Hong Kong. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Qiao, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; et al. Fine Particulate Matter Constituents, Nitric Oxide Synthase DNA Methylation and Exhaled Nitric Oxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11859–11865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Cai, M.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Vaughn, M.G.; Aaron, H.E.; Wu, F.; et al. Constituents of Fine Particulate Matter and Asthma in 6 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 150, 214–222.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappazzo, K.M.; Daniels, J.L.; Messer, L.C.; Poole, C.; Lobdell, D.T. Exposure to Elemental Carbon, Organic Carbon, Nitrate, and Sulfate Fractions of Fine Particulate Matter and Risk of Preterm Birth in New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania (2000–2005). Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ostro, B.; Roth, L.; Malig, B.; Marty, M. The Effects of Fine Particle Components on Respiratory Hospital Admissions in Children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, C.; Shen, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. Chronic Exposure to PM2.5 Nitrate, Sulfate, and Ammonium Causes Respiratory System Impairments in Mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3081–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, S.; Shao, X.; Wang, C.; Chung, S.K.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, K. Exposure to Airborne PM2.5 Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions Induces a Wide Array of Reproductive Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4092–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, W.; Li, S.; He, C.; Dai, Y.; Feng, S.; Zeng, C.; Yang, T.; Meng, Q.; Meng, J.; et al. Ambient PM2.5 and Its Components Associated with 10-Year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Chinese Adults. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 263, 115371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Al-Aly, Z.; Zheng, B.; Donkelaar, A.v.; Martin, R.V.; Pineau, C.A.; Bernatsky, S. Fine Particulate Matter Components and Interstitial Lung Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, P.; Frossi, B.; Pala, G.; Negri, S.; Oman, H.; Perfetti, L.; Pucillo, C.; Imbriani, M.; Moscato, G. Oxidative Activity of Ammonium Persulfate Salt on Mast Cells and Basophils: Implication in Hairdressers’ Asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 160, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Lin, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, T.; Yuan, L.; Pan, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Source Apportionment of Ammonium in Atmospheric PM2.5 in the Pearl River Delta Based on Nitrogen Isotope. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 31, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Lin, H. Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Fine Particulate Matter Chemical Composition and in-Hospital Case Fatality among Patients with Stroke in China. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 32, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segersson, D.; Eneroth, K.; Gidhagen, L.; Johansson, C.; Omstedt, G.; Nylén, A.E.; Forsberg, B. Health Impact of PM10, PM2.5 and Black Carbon Exposure Due to Different Source Sectors in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Umea, Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wei, Y.; Schwartz, J.D. Long-Term Exposure to Ambient PM2.5 and Hospitalizations for Myocardial Infarction Among US Residents: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Escobar, G.; Schwalb, A.; Tello-Lizarraga, K.; Vega-Guerovich, P.; Ugarte-Gil, C. Spatio-Temporal Co-Occurrence of Hotspots of Tuberculosis, Poverty and Air Pollution in Lima, Peru. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.P.; Swanepoel, L.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G.; Egami, R.T. The Comparison of Source Contributions from Residential Coal and Low-Smoke Fuels, Using CMB Modeling, in South Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy 2002, 5, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution and Health. WHO Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Aunan, K.; Hansen, M.H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S. The Hidden Hazard of Household Air Pollution in Rural China. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, C.-E.; Gerde, P.; Hanberg, A.; Jernström, B.; Johansson, C.; Kyrklund, T.; Rannug, A.; Törnqvist, M.; Victorin, K.; Westerholm, R. Cancer Risk Assessment, Indicators, and Guidelines for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Ambient Air. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 451–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.O.; Han, Y.; Lam, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Bacon-Shone, J. Air Pollution and Environmental Injustice: Are the Socially Deprived Exposed to More PM2.5 Pollution in Hong Kong? Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 80, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, S. Global Atmospheric Emission Inventory of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) for 2004. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.G. An Overview of PM2.5 Sources and Control Strategies. Fuel Process. Technol. 2000, 65–66, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowka, W.I.; Luo, J.; Craver, A.; Pinto, J.M.; Ahsan, H.; Olopade, C.S.; Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B. Household Air Pollution Disparities between Socioeconomic Groups in Chicago. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 091002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajeri, N.; Hsu, S.-C.; Milner, J.; Taylor, J.; Kiesewetter, G.; Gudmundsson, A.; Kennard, H.; Hamilton, I.; Davies, M. Urban–Rural Disparity in Global Estimation of PM2.5 Household Air Pollution and Its Attributable Health Burden. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Wang, S.; Aunan, K.; Zhao, M.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Hansen, M.H. Personal Exposure to PM2.5 in Chinese Rural Households in the Yangtze River Delta. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Bruce, N.; Balakrishnan, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Balmes, J.; Chafe, Z.; Dherani, M.; Hosgood, H.D.; Mehta, S.; Pope, D.; et al. Millions Dead: How Do We Know and What Does It Mean? Methods Used in the Comparative Risk Assessment of Household Air Pollution. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Padilla, R.; Schilmann, A.; Riojas-Rodriguez, H. Respiratory Health Effects of Indoor Air Pollution. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2010, 14, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Prüss-Üstün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, D.M.; World Health Organization. Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-156519-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lueckmann, S.L.; Hoebel, J.; Roick, J.; Markert, J.; Spallek, J.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Richter, M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Primary-Care and Specialist Physician Visits: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, A.H.; Pollack, C.C.; Schultheiss, M.D.; Brownstein, J.S. Delayed Medical Care and Underlying Health in the United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.S.; Jerrett, M.; Kawachi, I.; Levy, J.I.; Cohen, A.J.; Gouveia, N.; Wilkinson, P.; Fletcher, T.; Cifuentes, L.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Health, Wealth, and Air Pollution: Advancing Theory and Methods. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zanobetti, A.; Wang, Y.; Koutrakis, P.; Choirat, C.; Dominici, F.; Schwartz, J.D. Air Pollution and Mortality in the Medicare Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitshak-Sade, M.; Bobb, J.F.; Schwartz, J.D.; Kloog, I.; Zanobetti, A. The Association between Short and Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 and Temperature and Hospital Admissions in New England and the Synergistic Effect of the Short-Term Exposures. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, M.C.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Flanders, W.D.; Qin, X.; Garbe, P. Outdoor PM2.5, Ambient Air Temperature, and Asthma Symptoms in the Past 14 Days among Adults with Active Asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1882–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Dong, H.; Li, M.; Huang, L.; Lin, G.; Liu, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, J. Interactive Effects Between Temperature and PM2.5 on Mortality: A Study of Varying Coefficient Distributed Lag Model—Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China, 2013–2020. China CDC Wkly. 2022, 4, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ye, D.; Li, N.; Bi, P.; Tong, S.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, X. High Temperatures and Emergency Department Visits in 18 Sites with Different Climatic Characteristics in China: Risk Assessment and Attributable Fraction Identification. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Bao, J.; Xiang, H.; Dear, K.; Liu, Q.; Lin, S.; Lawrence, W.R.; Lin, A.; et al. Humidity May Modify the Relationship between Temperature and Cardiovascular Mortality in Zhejiang Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Song, J.; Su, H. Impact of Diurnal Temperature Range on Human Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, S. Characteristics of Secondary PM2.5 Under Different Photochemical Reactivity Backgrounds in the Pearl River Delta Region. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 837158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zheng, C.; Shang, Y. Ambient Temperature Enhanced Acute Cardiovascular-Respiratory Mortality Effects of PM2.5 in Beijing, China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Kang, H.-J.; Kim, H.; Seo, Y.-K.; Shin, H.-J.; Ghim, Y.S.; Song, C.-K.; Choi, S.-D. Pollution Characteristics of PM2.5 during High Concentration Periods in Summer and Winter in Ulsan, the Largest Industrial City in South Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 292, 119418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Hugentobler, W.J.; Iwasaki, A. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020, 7, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, C.R.; Wellenius, G.A.; Diaz, E.A.; Lawrence, J.; Coull, B.A.; Akiyama, I.; Lee, L.M.; Okabe, K.; Verrier, R.L.; Godleski, J.J. Mechanisms of Inhaled Fine Particulate Air Pollution–Induced Arterial Blood Pressure Changes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R.A.; Camilli, M.; Russo, M.; Termite, C.; La Vecchia, G.; Iannaccone, G.; Rinaldi, R.; Gurgoglione, F.; Del Buono, M.G.; Sanna, T.; et al. Air Pollution and Coronary Plaque Vulnerability and Instability: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y. Short-Term Exposure to PM2.5 Constituents, Extreme Temperature Events and Stroke Mortality. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, W.; Liao, C.; Luo, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Strategies for PM2.5 in Guangdong Province to Achieve the WHO-II Air Quality Target from the Perspective of Synergistic CO2 Co-Benefit Control. Res. Environ. Sci. 2021, 34, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Popek, R.; Przybysz, A.; Roy, A.; Das, S.; Sarkar, A. Breathing Fresh Air in the City: Implementing Avenue Trees as a Sustainable Solution to Reduce Particulate Pollution in Urban Agglomerations. Plants 2023, 12, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniuszko, H.; Popek, R.; Nawrocki, A.; Stankiewicz-Kosyl, M.; Grylewicz, S.; Podoba, S.; Przybysz, A. Urban Meadow-a Recipe for Long-Lasting Anti-Smog Land Cover. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2024, 26, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, N.; Li, M.; Chang, S.; Tang, X.; Liang, S. Strategic studies on the adjustment of industrial structure in Guangdong Province to achieve PM2.5 air quality targets. Environ. Pollut. Control 2020, 42, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, S. Driving Force behind PM 2.5 Pollution in Guangdong Province Based on the Interaction Effect of Institutional Background and Socioeconomic Activities. Trop. Geogr. 2020, 40, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, G.L.; Fu, N.; Wang, P.S.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.Z.; Shen, G.F.; Lin, N.; Du, W. Assessing PM2.5 exposure of rural residents in Southwest China using real-time monitoring and movement trajectory analysis. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2025, 20, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, B.G. Effect of Measurement Error on Epidemiological Studies of Environmental and Occupational Exposures. Occup. Environ. Med. 1998, 55, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).