Microbiological and Chemical Quality of Portuguese Lettuce—Results of a Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

2.3. Chemical Safety Analysis

2.3.1. Chemicals, Materials and Standards

2.3.2. Nitrate Concentration

2.3.3. Pesticides Determination

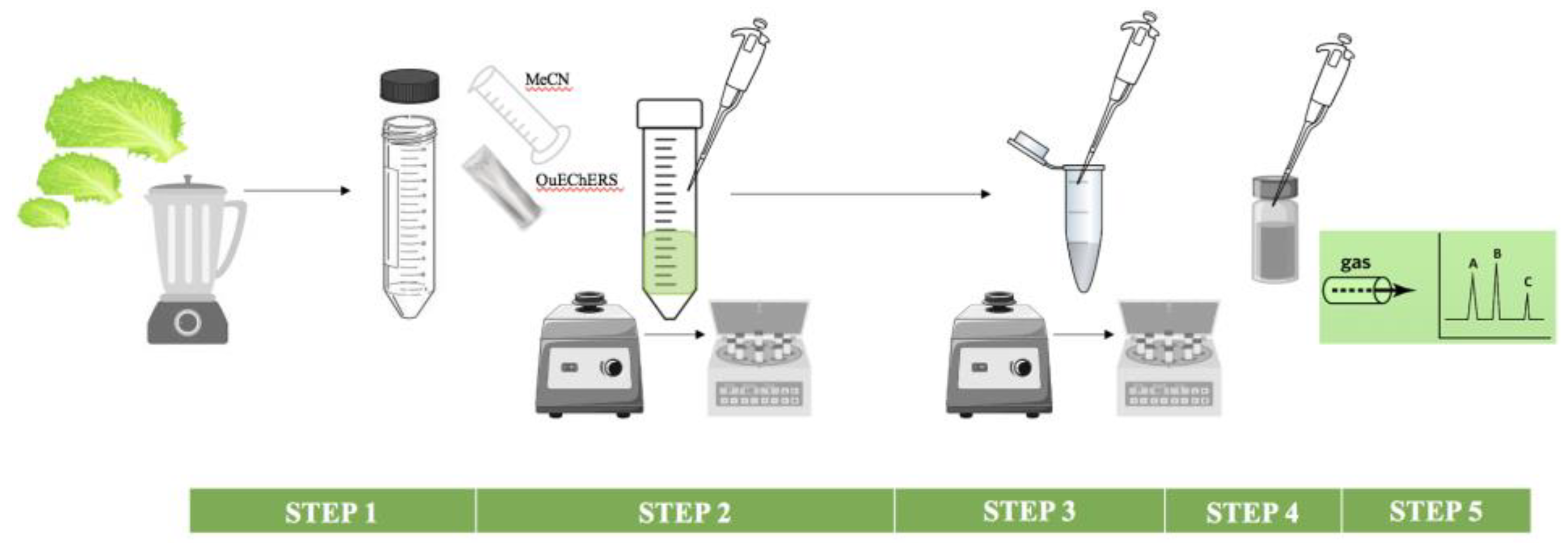

Sample Preparation

Method Validation

GC Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microbiological Analysis

3.2. Nitrate Concentration

3.3. Pesticide Analysis

3.3.1. Method Evaluation

3.3.2. Sample Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bars-Cortina, D.; Martínez-Bardají, A.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.-J.; Piñol-Felis, C. Consumption evaluation of one apple flesh a day in the initial phases prior to adenoma/adenocarcinoma in an azoxymethane rat colon carcinogenesis model. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 83, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, D.W.K.; Koh, E.S.; Kim, J.E. Incorporating healthy dietary changes in addition to an increase in fruit and vegetable intake further improves the status of cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review, meta-regression, and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 78, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstens, C.K.; Salazar, J.K.; Darkoh, C. Multistate outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States associated with fresh produce from 2010 to 2017. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Machado-Moreira, B.; Richards, K.; Brennan, F.; Abram, F.; Burgess, C.M. Microbial contamination of fresh produce: What, where, and how? Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1727–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, D. 2019’s Top 10 Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks by Number Of Illnesses. Food Safety News, 2019. Available online: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2019/12/2019s-top-10-multistate-foodborne-outbreaks-by-number-of-illnesses/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Thompson, L.A.; Darwish, W.S. Environmental chemical contaminants in food: Review of a global problem. J. Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nasreddine, L.; Rehaime, M.; Kassaify, Z.; Rechmany, R.; Jaber, F. Dietary exposure to pesticide residues from foods of plant origin and drinks in Lebanon. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stachniuk, A.; Szmagara, A.; Czeczko, R.; Fornal, E. LC-MS/MS determination of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2017, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EWG Science Team. Dirty Dozen: EWG’s 2020 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce. Available online: https://www.ewg.org/foodnews/full-list.php (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Medina-Pastor, P.; Triacchini, G. European Food Safety Authority The 2018 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Araújo, D.F.S.; Da Silva, A.M.R.B.; Lima, L.L.D.A.; Vasconcelos, M.A.D.S.; Andrade, S.A.C.; Sarubbo, L. The concentration of minerals and physicochemical contaminants in conventional and organic vegetables. Food Control 2014, 44, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Barreira, S.V.P.; Costa, A.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Organic versus conventional tomatoes: Influence on physicochemical parameters, bioactive compounds and sensorial attributes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 67, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Miranda, M.; Orjales, I.; Villamayor, M.J.G.; Al-Soufi, W.; López-Alonso, M. Consumers’ perception of and attitudes towards organic food in Galicia (Northern Spain). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimler, D.; Vignolini, P.; Arfaioli, P.; Isolani, L.; Romani, A. Conventional, organic and biodynamic farming: Differences in polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of Batavia lettuce. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 92, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia, J.M.; Teixeira, P. Organic versus conventional food: A comparison regarding food safety. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 33, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, D.T.; Antunes, A.E.C.; Da Rocha, J.G.; Dutra, T.G.; Manfrinato, C.V.; Oliveira, J.M.; Rostagno, M.A. Differences between organic and conventional leafy green vegetables perceived by university students. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1579–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No. 396/2005 of the European parliament and of the council of 23 February 2005 on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending council directive 91/414/EEC. J. Eur. Communities 2005, 70, 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority. The 2017 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konatu, F.R.B.; Breitkreitz, M.C.; Jardim, I.C.S.F. Revisiting quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe parameters for sample preparation in pesticide residue analysis of lettuce by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1482, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel-León, J.M.; Duy, S.V.; Munoz, G.; Verner, M.-A.; Hendawi, M.Y.; Moya, H.; Amyot, M.; Sauvé, S.; Rojas, H.E.M. Occurrence of pesticides in fruits and vegetables from organic and conventional agriculture by QuEChERS extraction liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Food Control 2019, 104, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wan, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Lew, H.; Yang, H. Analysis of organophosphorus and pyrethroid pesticides in organic and conventional vegetables using QuEChERS combined with dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction based on the solidification of floating organic droplet. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Usall, J.; Viñas, I.; Anguera, M.; Gatius, F.; Abadias, M. Microbiological quality of fresh lettuce from organic and conventional production. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.D.Q.; Loiko, M.R.; De Paula, C.M.D.; Hessel, C.T.; Jacxsens, L.; Uyttendaele, M.; Bender, R.J.; Tondo, E.C. Microbiological contamination linked to implementation of good agricultural practices in the production of organic lettuce in Southern Brazil. Food Control 2014, 42, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, C.-H.; Rukayadi, Y.; Ahmad, S.H.; Radzi, C.W.J.W.M.; Thung, T.Y.; Premarathne, J.M.K.J.K.; Chang, W.-S.; Loo, Y.-Y.; Tan, C.-W.; Ramzi, O.B.; et al. Comparison of the microbiological quality and safety between conventional and organic vegetables sold in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 15214: 1998. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Mesophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria—Colony-Count Technique at 30 °C; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 21528-2: 2017. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae—Part 2: Colony-Count Technique; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 16649-2: 2001. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Beta-Glucuronidase-Positive Escherichia coli—Part 2: Colony-Count Technique at 44 °C Using 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl Beta-D-Glucuronide; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 11290-1: 2017. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 1: Detection Method; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 21527-1: 2008. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Yeasts and Moulds—Part 1: Colony Count Technique in Products with Water Activity Greater Than 0.95; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 4833-2, 2013. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms—Part 2: Colony Count at 30 °C by the Surface Plating Technique; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 13720: 2010. Meat and Meat Products—Enumeration of Presumptive Pseudomonas spp.; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 11290-2: 2017. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 2: Enumeration Method; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 6579-1, 2017. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp.; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.L.F.C.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Souto, M.R.S. Flow injection determination of nitrate in vegetables using a tubular potentiometric detector. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Lehotay, S.J.; Geis-Asteggiante, L.; Kwon, H.; Mol, H.G.J.; Van Der Kamp, H.; Mateus, N.; Domingues, V.; Delerue-Matos, C. Analysis of pesticide residues in strawberries and soils by GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS and two-dimensional GC-time-of-flight MS comparing organic and integrated pest management farming. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noronha, L.; Castro, A.; Ferreira, V.; Magalhães, R.; Almeida, G.; Mena, C.; Silva, J.; Teixeira, P. Study of biological hazards present on the surfaces of selected fruits and vegetables. Am. J. Food Technol. 2016, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Gutierrez, A.; Burns, I.G.; Lee, A.; Edmondson, R.N. Screening lettuce cultivars for low nitrate content during summer and winter production. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Opinion of the scientific panel on contaminants in the food chain on a request from the European Commission to perform a scientific risk assessment on nitrate in vegetables. EFSA J. 2008, 689, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Laia, R.; Rebelo, A.; Serra, C.; Vasco, E. Teor de nitrato em produtos hortícolas e frutos consumidos ao longo do ano em Portugal. Bol. Epidemiólogico Obs. 2018, 5, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate General for Health and Food Safety. SANTE/11813/2017—Guidance Document on Analytical Quality Control and Method Validation Procedures for Pesticide Residues and Analysis in Food and Feed. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/plant/docs/pesticides_mrl_guidelines_wrkdoc_2017-11813.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Olisah, C.; Okoh, O.O.; Okoh, A.I. Occurrence of organochlorine pesticide residues in biological and environmental matrices in Africa: A two-decade review. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolani, L.; Mawussi, G.; Sanda, K. Assessment of organochlorine pesticide residues in vegetable samples from some agricultural areas in Togo. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2016, 7, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruzeiro, C.R.; Amaral, S.; Rocha, E.; Rocha, E. Determination of 54 pesticides in waters of the Iberian Douro River estuary and risk assessment of environmentally relevant mixtures using theoretical approaches and Artemia salina and Daphnia magna bioassays. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 145, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Tiritan, M.E. Occurrence of persistent organic pollutants in sediments and biota from Portugal versus European incidence: A critical overview. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2015, 51, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, V.; Domingues, V.; Mateus, N.; Delerue-Matos, C. Organochlorine pesticide residues in strawberries from integrated pest management and organic farming. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7582–7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, V.; Freitas, M.; Pacheco, J.P.G.; Oliveira, J.M.; Domingues, V.; Delerue-Matos, C. Magnetic dispersive micro solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography determination of organophosphorus pesticides in strawberries. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1566, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pestana, D.; Faria, G.; Sá, C.; Fernandes, V.; Teixeira, D.; Norberto, S.; Faria, A.; Meireles, M.; Marques, C.; Correia-Sá, L.; et al. Persistent organic pollutant levels in human visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese individuals—Depot differences and dysmetabolism implications. Environ. Res. 2014, 133, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| GC-ECD | GC-FPD | GC/MS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment | Shimadzu GC-2010 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | Shimadzu GC-2010 Plus gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) | Thermo Trace-Ultra GC from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) coupled to an ion trap mass detector Thermo Polaris |

| Column | Zebron-5MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm film | ||

| Carrier Gas | Helium at 1 mL min−1 | ||

| Injection | 2 µL splitless | ||

| Temperature: Injector Detector | 250 °C | 250 °C | 250 °C |

| 300 °C | 290 °C | Transfer line 250 °C/Ion source 270 °C | |

| Temperature program | Initial 40 °C, hold 1 min, then 20 °C/min to 120 °C, hold 1 min, next 10 °C/min to 150 °C, hold 1 min, next 10 °C/min to 180 °C, hold 1 min, next 20 °C/min to 200 °C, hold 1 min, next 10 °C/min to 290 °C and hold 2 min. | Initial 100 °C, hold 1 min, then 20 °C/min to 150 °C, hold 1 min, next 2 °C/min to 180 °C, hold 2 min, and 20 °C/min to 270 °C and hold for 1 min. | Same as ECD |

| Total running time | 27 min | 26 min | 27 min |

| Others: | SIM mode confirmation α-HCH | m/z 109, 181, 219 | ||

| Log (CFU/g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Mode | Sample | Enterobacteria | Total Counts | Lactic Acid Bacteria | Pseudomonas Spp. | Molds | Yeasts |

| Conventional | Conv1 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 4.3 | 6.0 |

| Conv2 | 4.3 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 7.4 | 4.6 | 7.2 | |

| Conv3 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 3.4 | 1 | 4.5 | 5.3 | |

| Conv4 | 4.9 | 8.0 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 5.6 | |

| Conv5 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 5.9 | |

| Conv6 | 7.0 | 8.9 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 5.1 | 5.5 | |

| Conv7 | 4.9 | 8.5 | * | 7.0 | 4.4 | 7.1 | |

| Conv8 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 4.2 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 6.4 | |

| Conv9 | 6.0 | 9.2 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 7.0 | |

| Conv10 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 1.0 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 5.8 | |

| Average ± SD | 5.9 ± 1.0 | b 8.4 ± 0.54 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 0.41 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | |

| Organic | Org1 | 4.7 | 7.8 | 3.4 | 7.6 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Org2 | <1 | 7.2 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 5.2 | |

| Org3 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 6.1 | |

| Org4 | 3.0 | 7.4 | 1.0 | 7.2 | 4.9 | 9.2 | |

| Org5 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 4.5 | |

| a Org6 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 3.3 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 6.3 | |

| a Org7 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 5.0 | 5.6 | |

| a Org8 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 5.3 | 6.3 | |

| Org9 | 6.1 | 8.0 | * | 7.4 | 4.5 | 6.7 | |

| Org10 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 1.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 6.4 | |

| Average ± SD | 5.2 ± 1.5 | b 7.6 ± 0.72 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 6.1 ± 1.4 | |

| Production Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Organic | ||

| Sample | Nitrate (mg/kg) | Sample | Nitrate (mg/kg) |

| Conv1 | 1290 | Org1 | 1550 |

| Conv2 | 1760 | Org2 | 1530 |

| Conv3 | 1650 | Org3 | 1720 |

| Conv4 | 1590 | Org4 | 1670 |

| Conv5 | 1630 | Org5 | 1410 |

| Conv6 | * | a Org6 | 1580 |

| Conv7 | * | a Org7 | 1610 |

| Conv8 | 1950 | a Org8 | * |

| Conv9 | 1370 | Org9 | 1480 |

| Conv10 | 1606 | Org10 | 1569 |

| Average ± SD | 1606 ± 207 | 1569 ± 93 | |

| Recoveries ± Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) (%) (n = 3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytes | MRL * µg/kg | Coefficient of Determination | LOQ µg/kg | 25 µg/kg | 50 µg/kg | 100 µg/kg | |

| Organophosphorus pesticides | Diazinon | 10 | 0.9956 | 1.13 | 78 ± 15 | 81 ± 18 | 85 ± 17 |

| Chlorpyrifos-methyl | 10 | 0.9929 | 1.57 | 70 ± 12 | 84 ± 10 | 83 ± 13 | |

| Parathion-methyl | 10 | 0.9989 | 0.57 | 74 ± 17 | 95 ± 9 | 80 ± 15 | |

| Malathion | 500 | 0.9982 | 0.72 | 55 ± 20 | 60 ± 10 | 65 ± 14 | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 | 0.9963 | 1.03 | 79 ± 10 | 87 ± 17 | 90 ± 16 | |

| Chlorfenvinphos | 10 | 0.9956 | 1.13 | 71 ± 16 | 83 ± 10 | 79 ± 9 | |

| Organochlorine pesticides | α-HCH | 10 | 0.9980 | 0.77 | 85 ± 16 | 90 ± 8 | 87 ± 18 |

| HCB | 10 | 0.9927 | 1.46 | 90 ± 15 | 95 ± 15 | 90 ± 9 | |

| β-HCH | 10 | 0.9960 | 1.08 | 78 ± 11 | 84 ± 10 | 80 ± 12 | |

| lindane (γ-HCH) | 10 | 0.9944 | 1.11 | 89 ± 20 | 97 ± 11 | 90 ± 14 | |

| ζ-HCH | 10 | 0.9900 | 1.49 | 75 ± 8 | 82 ± 8 | 80 ± 1 | |

| Aldrin | 10 | 0.9976 | 0.73 | 79 ± 7 | 84 ± 7 | 79 ± 7 | |

| Endosulfan I | 50 | 0.9943 | 1.12 | 80 ± 2 | 89 ± 5 | 85 ± 4 | |

| p.p’-DDE | 50 | 0.9932 | 1.13 | 81 ± 2 | 92 ± 5 | 90 ± 1 | |

| Dieldrin | 10 | 0.9979 | 0.80 | 90 ± 5 | 94 ± 11 | 90 ± 9 | |

| Endrin | 10 | 0.9925 | 1.79 | 78 ± 5 | 86 ± 8 | 82 ± 4 | |

| DDT # | 50 | 0.9958 | 0.96 | 72 ± 6 | 81 ± 10 | 80 ± 5 | |

| p.p′-DDD | 50 | 0.9913 | 1.59 | 75 ± 19 | 82 ± 11 | 78 ± 11 | |

| Endosulfan II | 50 | 0.9956 | 0.79 | 82 ± 2 | 90 ± 9 | 86 ± 1 | |

| Methoxychlor | 0.9994 | 0.78 | 73 ± 2 | 80 ± 7 | 79 ± 3 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, C.; Lopes, F.; Costa, R.; Komora, N.; Ferreira, V.; Cruz Fernandes, V.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Teixeira, P. Microbiological and Chemical Quality of Portuguese Lettuce—Results of a Case Study. Foods 2020, 9, 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091274

Ferreira C, Lopes F, Costa R, Komora N, Ferreira V, Cruz Fernandes V, Delerue-Matos C, Teixeira P. Microbiological and Chemical Quality of Portuguese Lettuce—Results of a Case Study. Foods. 2020; 9(9):1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091274

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Catarina, Filipa Lopes, Reginaldo Costa, Norton Komora, Vânia Ferreira, Virgínia Cruz Fernandes, Cristina Delerue-Matos, and Paula Teixeira. 2020. "Microbiological and Chemical Quality of Portuguese Lettuce—Results of a Case Study" Foods 9, no. 9: 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091274