Persistence and Effect of a Multistrain Starter Culture on Antioxidant and Rheological Properties of Novel Wheat Sourdoughs and Bread

Abstract

1. Introduction

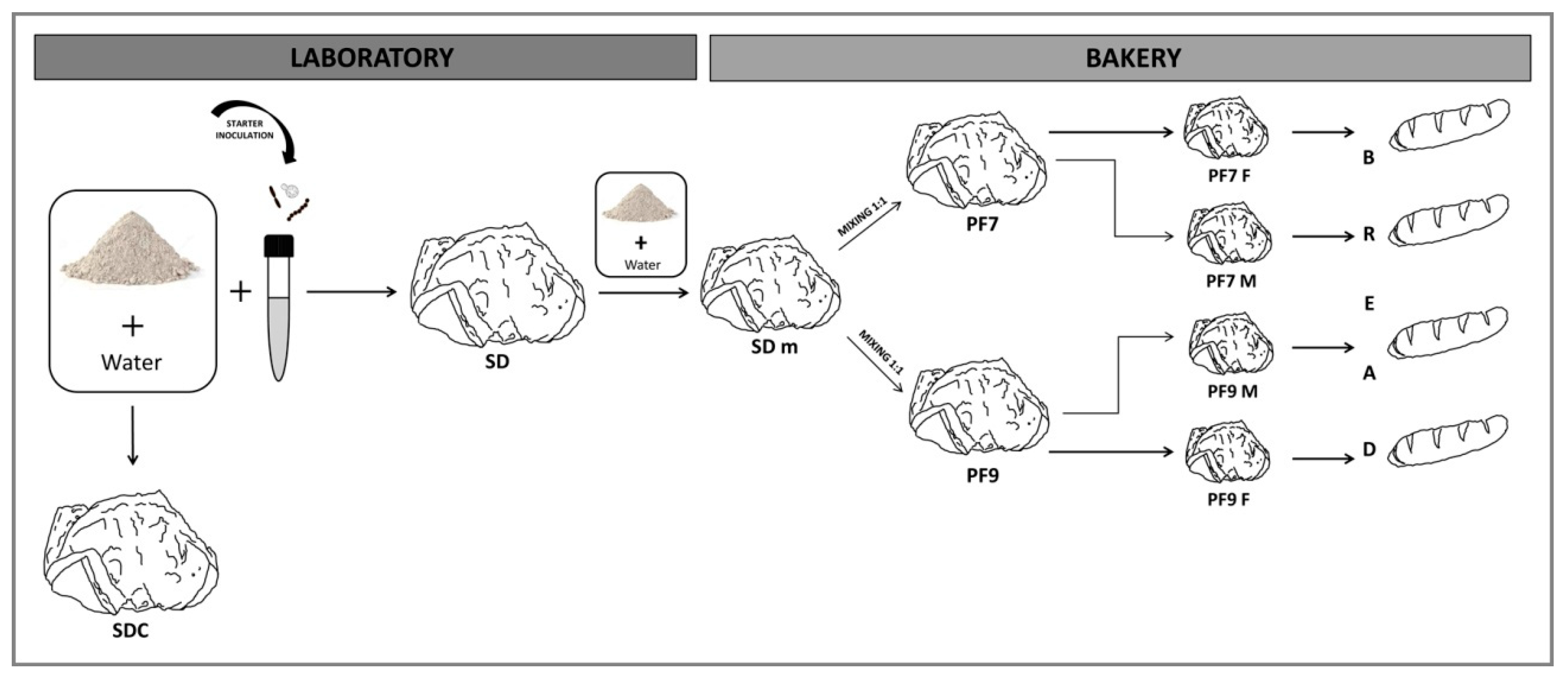

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

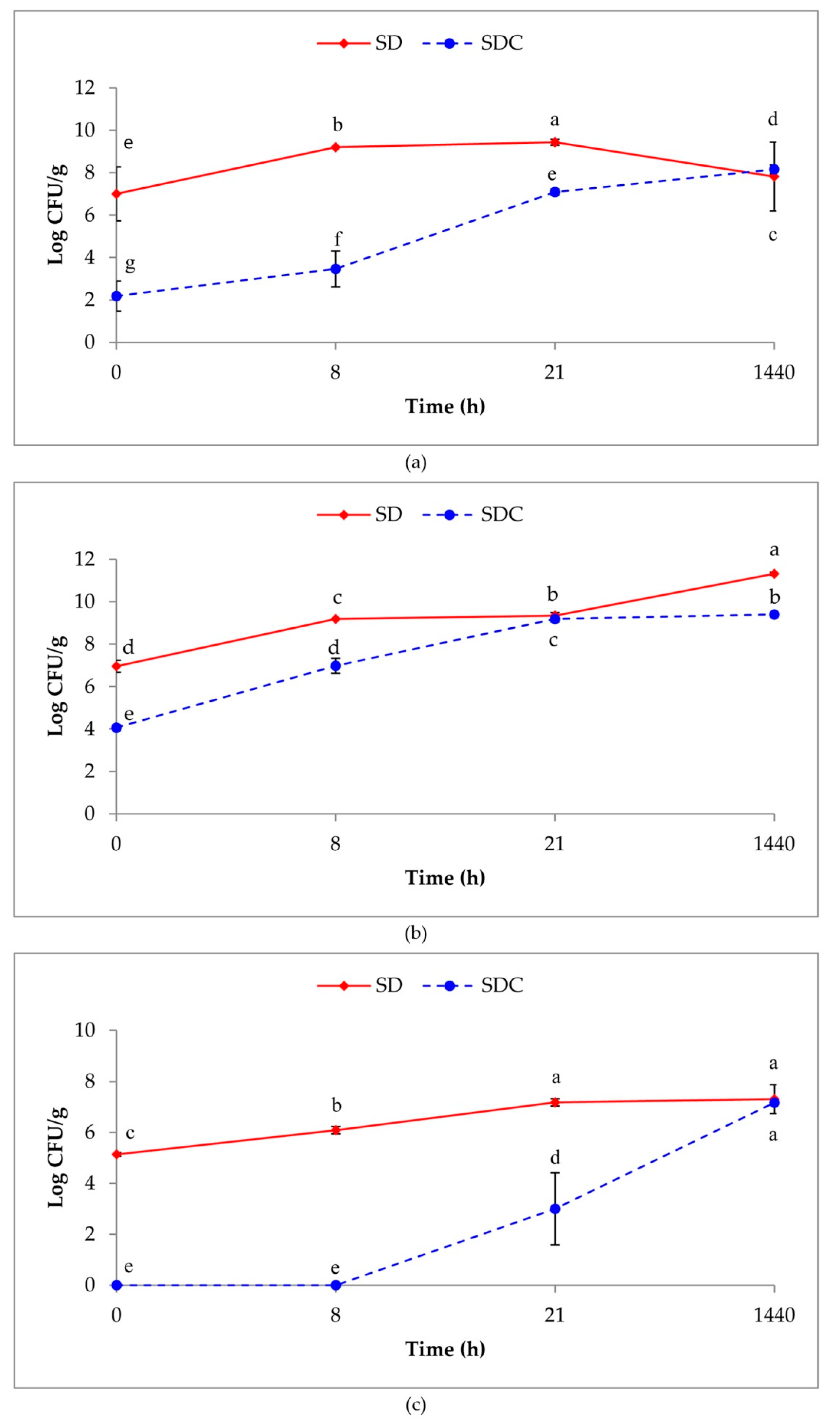

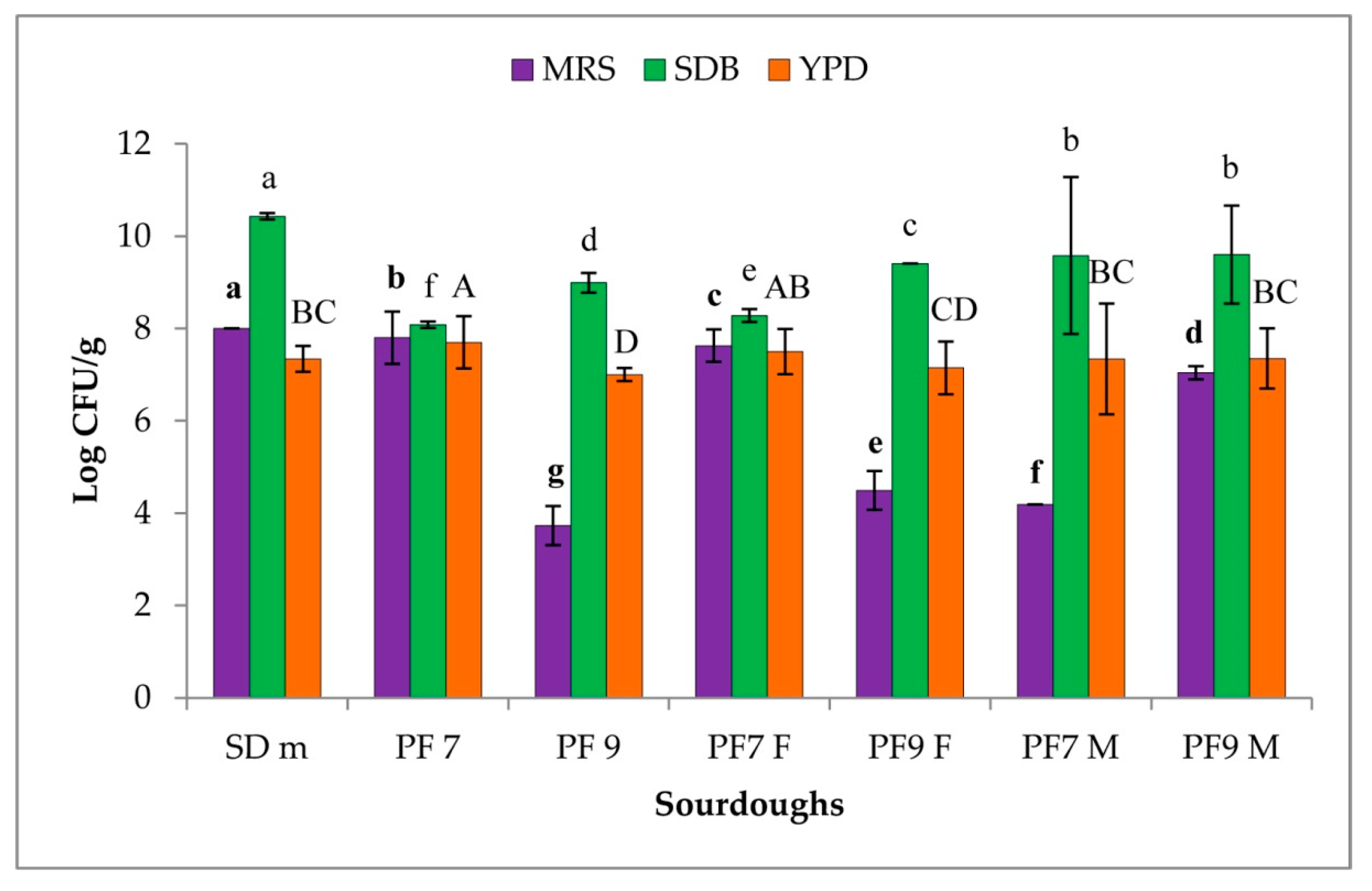

3.1. Microbial Count

3.2. Persistence of the MultiStrain Starter

3.3. Microbial Community Fingerprinting by PCR-DGGE

3.4. Chemical Characterization of Sourdoughs and Breads

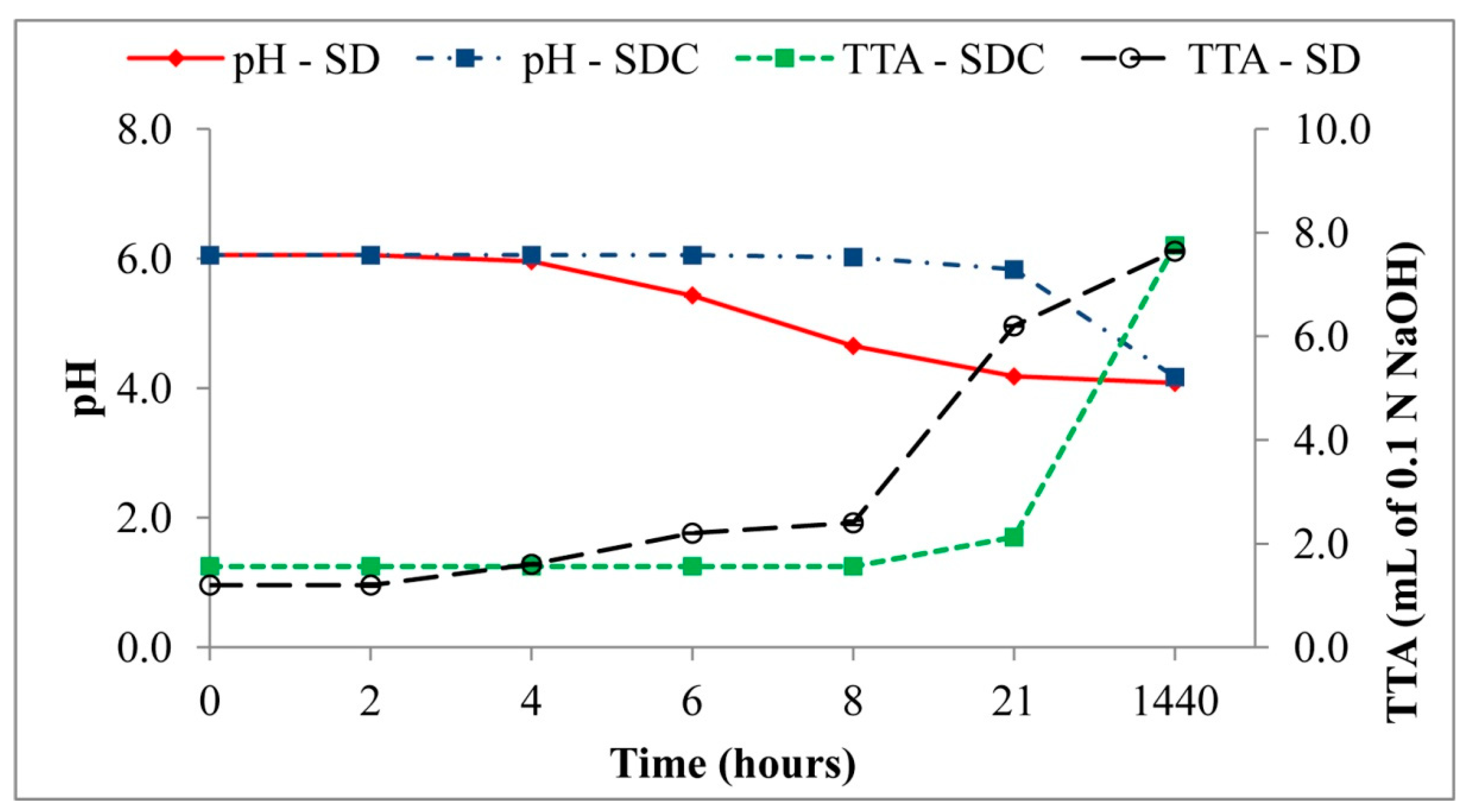

3.4.1. pH, TTA, and Organic Acids

3.4.2. Total Phenols and DPPH Assay

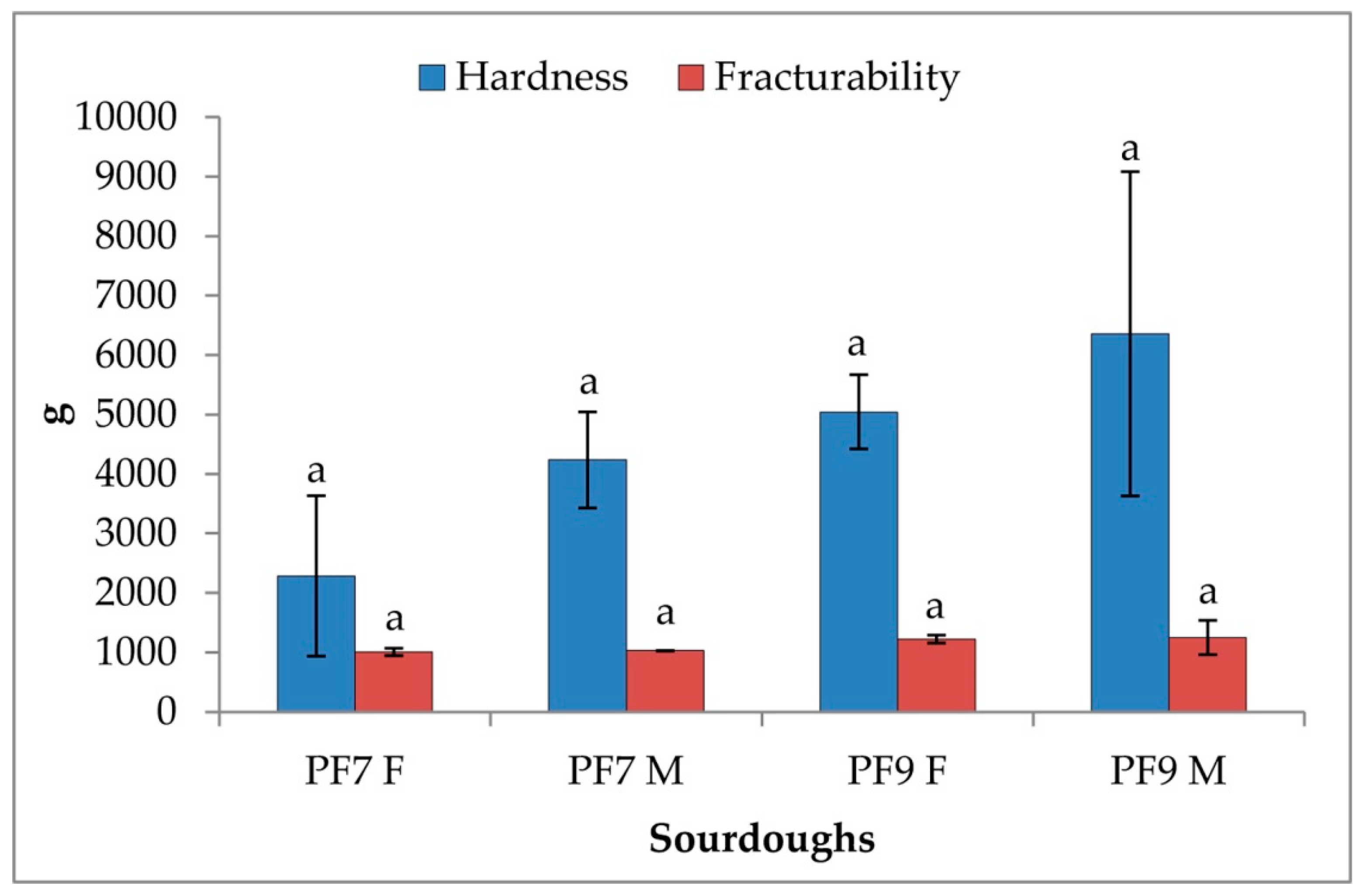

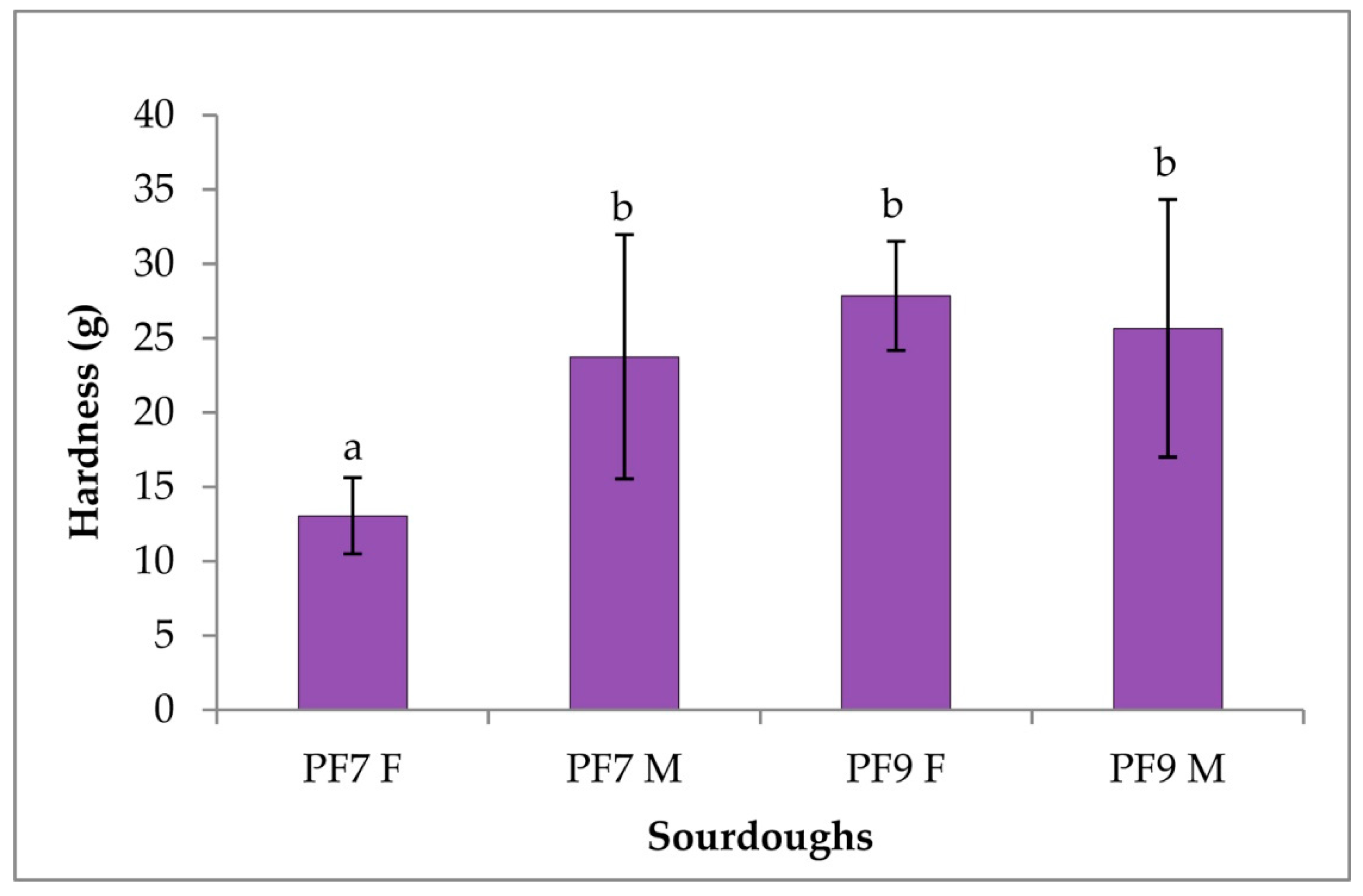

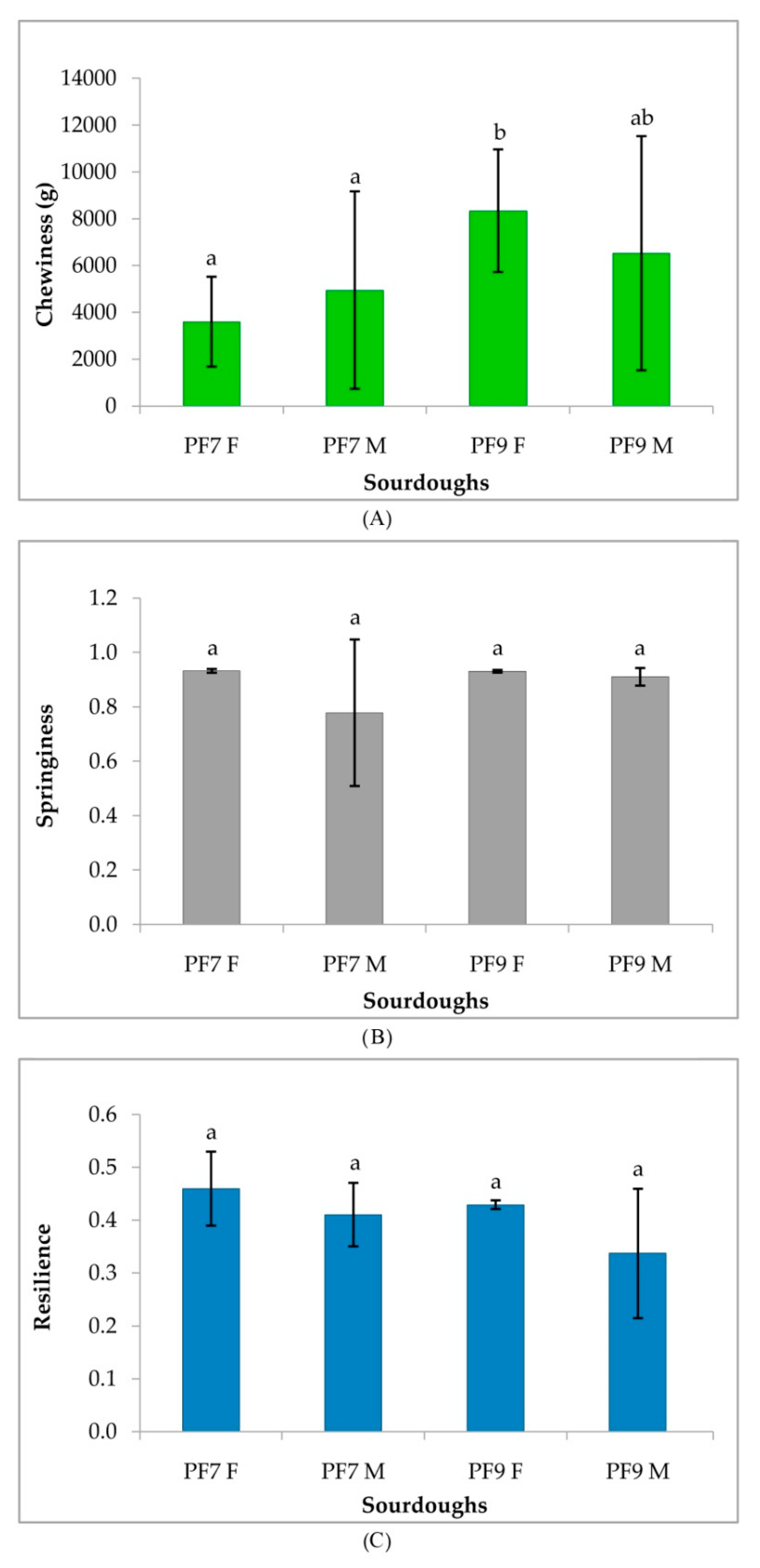

3.4.3. Rheological Characterization of Sourdoughs and Bread

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liukkonen, K.H.; Katina, K.; Wilhelmson, A.; Myllymäki, O.; Lampi, A.M.; Kariluoto, S.; Piironen, V.; Heinonen, S.M.; Nurmi, T.; Adlercreutz, H.; et al. Process-induced changes on bioactive compounds in whole grain rye. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, E.K.; Ryan, L.A.M.; Dal Bello, F. Impact of sourdough on the texture of bread. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Kaukovirta-Norja, A.; Adlercreutz, H.; Heinonen, S.M.; Lampi, A.-M.; Pihlava, J.M.; Poutanen, K. Fermentation-induced changes in the nutritional value of native or germinated rye. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutanen, K.; Flander, L.; Katina, K. Sourdough and cereal fermentation in a nutritional perspective. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridi, A.; Sidari, R. Safety and healthiness enhancement of red wines by selected microbial starters. In Red Wine and Health; O’Byrne, P., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrè, A.M. HPLC-DAD detection of changes in phenol content of red berry skins during grape ripening. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskou, D. Phenolic compounds in olives and olive oil. In Olive Oil: Minor Constituents and Health; Boskou, D., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Jacobs, D.; Marquart, L. Grain processing and nutrition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 40, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarter, N.; Liu, R. Health benefits of whole grain phytochemicals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilić, S. Phenolic compounds of wheat their content, antioxidant capacity and bioaccessibility. MOJ Food Process Technol. 2016, 2, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Hecker, K.D.; Bonanome, A.; Coval, S.M.; Binkoski, A.E.; Hilpert, K.F.; Griel, A.E.; Etherton, T.D. Bioactive compounds in foods: Their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 2002, 113, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.-Q.; Deng, G.-F.; Guo, Y.-J.; Li, H.-B. Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Yu, L.; Lu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Liu, L.; Costa, J.; Yu, L. Phytochemical compositions, and antioxidant properties, and antiproliferative activities of wheat flour. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridi, A.; Sidari, R.; Giuffrè, A.M.; Pellicanò, T.M.; Sicari, V.; Zappia, C.; Poiana, M. Test of four generations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae concerning their effect on antioxidant phenolic compounds in wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrè, A.M. The evolution of free acidity and oxidation related parameters in olive oil during olive ripening from cultivars grown in the region of Calabria, South Italy. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2018, 30, 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Tamang, J.P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W.H. Review: Diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidari, R.; Martorana, A.; De Bruno, A. Effect of brine composition on yeast biota associated with naturally fermented Nocellara messinese table olives. LWT 2019, 109, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Fazzino, F.; Sidari, R.; Zema, D.A. Optimization of orange peel waste ensiling for sustainable anaerobic digestion. Renew. Energy 2020, 154, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Fazzino, F.; Folino, Z.; Scibetta, S.; Sidari, R. Improvement of semicontinuous anaerobic digestion of pre-treated orange peel waste by the combined use of zero valent iron and granular activated carbon. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 129, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Arendt, E.; Liukkonen, K.H.; Autio, K.; Flander, L.; Poutanen, K. Potential of sourdough for healthier cereal products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ðorđević, T.M.; Šiler-Marinković, S.S.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.I. Effect of fermentation on antioxidant properties of some cereals and pseudo cereals. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Di Cagno, R.; De Angelis, M. How the sourdough may affect the functional features of leavened baked goods. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.I.; Schober, T.J.; Arendt, E.K. Effect of single strain and traditional mixed strain starter cultures on rheological properties of wheat dough and on bread quality. Cereal Chem. 2002, 79, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, C.; Benedito De Barber, C.; Martinez Anaya, M.A. Microbial sourdoughs influence acidification properties and breadmaking potential of wheat dough. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Corsetti, A.; Gobbetti, M.; De Marco, B.; Balestrieri, F.; Paoletti, L.; Rossi, J. Combined effect of sourdough lactic acid bacteria and additives on bread firmness and staling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3044–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Heiniö, R.-L.; Autio, K.; Poutanen, K. Optimization of sourdough process for improved sensory profile and texture of wheat bread. LWT 2006, 39, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flander, L.; Suortti, T.; Katina, K.; Poutanen, K. Effects of wheat sourdough process on the quality of mixed oat-wheat bread. LWT 2011, 44, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, A.; Holtekjølen, A.K.; Sahlstrøm, S.; Moldestad, A. Effect of barley and oat flour types and sourdoughs on dough rheology and bread quality of composite wheat bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 55, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, M.; Ertop, M.H. Evaluation of microtextural properties of sourdough wheat bread obtained from optimized formulation using scanning electron microscopy and image analysis during shelf life. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, E.; Garofalo, C.; Aquilanti, L.; Santarelli, S.; Silvestri, G.; Clementi, F. Microbiological and technological characterization of sourdoughs destined for bread-making with barley flour. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Park, S.H.; Ghafoor, K.; Hwang, S.Y.; Park, J. Quality and antioxidant properties of bread containing turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) cultivated in South Korea. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1577–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Coda, R.; Mazzacane, F.; Minervini, D.; Gobbetti, M. Micronized by-products from debranned durum wheat and sourdough fermentation enhanced the nutritional, textural and sensory features of bread. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikušová, L.; Gereková, P.; Kocková, M.; Šturdík, E.; Valachovičová, M.; Holubková, A.; Vajdák, M.; Mikuš, L. Nutritional, antioxidant, and glycaemic characteristics of new functional bread. Chem. Pap. 2013, 67, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontonio, E.; Nionelli, L.; Curiel, J.A.; Sadeghi, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Iranian wheat flours from rural and industrial mills: Exploitation of the chemical and technology features, and selection of autochthonous sourdough starters for making breads. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonzo, A.; Urso, V.; Corona, O.; Francesca, N.; Amato, G.; Settanni, L.; Di Miceli, G. Development of a method for the direct fermentation of semolina by selected sourdough lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 239, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Lorusso, A.; Russo, V.; Pinto, D.; Marzani, B.; Gobbetti, M. Improving the antioxidant properties of quinoa flour through fermentation with selected autochthonous lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaglio, R.; Alfonzo, A.; Barbera, M.; Franciosi, E.; Francesca, N.; Moschetti, G.; Settanni, L. Persistence of a mixed lactic acid bacterial starter culture during lysine fortification of sourdough breads by addition of pistachio powder. Food Microbiol. 2020, 86, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G.; Gentile, C.; Gaglio, R.; Perrone, A.; Guarcello, R.; Francesca, N.; Fretto, S.; Inglese, P.; Settanni, L. Effect of addition of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage on the biological leavening, physical, nutritional, antioxidant and sensory aspects of bread. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, F.; Di Cagno, R.; Lattanzi, A.; De Angelis, M.; Antonielli, L.; Cardinali, G.; Cappelle, S.; Gobbetti, M. Lactic acid bacterium and yeast microbiotas of 19 sourdoughs used for traditional/typical Italian breads: Interactions between ingredients and microbial species diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorana, A.; Giuffrè, A.M.; Capocasale, M.; Zappia, C.; Sidari, R. Sourdoughs as a source of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts with technological characteristics useful for improved bakery products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Maglaras, G.; Mamalis, S. Motivations and cognitive structures of consumers in their purchasing of functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, I.H. Motivation factors of consumers’ food choice. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 7, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkiene, E.; Steibliene, V.; Adomaitiene, V.; Juodeikiene, G.; Cernauskas, D.; Lele, L.; Klupsaite, D.; Zadeike, D.; Jarutiene, L.; Guiné, R.P.F. Factors affecting consumer food preferences: Food taste and depression-based evoked emotional expressions with the use of face reading technology. BioMed Res. Int. 2009, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, L.; Sugihara, T.F. Microorganisms of the San Francisco sour dough bread process. II. Isolation and characterization of undescribed bacterial species responsible for the souring activity. Appl. Microbiol. 1971, 21, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregersen, T. Rapid method for distinction of Gram-negative from Gram-positive bacteria. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1978, 5, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofalo, R.; Chaves-López, C.; Di Fabio, F.; Schirone, M.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S.; Paparella, A.; Suzzi, G. Molecular identification and osmotolerant profile of wine yeasts that ferment a high sugar grape must. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 130, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, V.; Torriani, S. Microbial population changes during sourdough fermentation monitored by DGGE analysis of 16S and 26S rRNA gene fragments. Ann. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSIBLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Viticut. 1997, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Haley, S.; Perret, J.; Harris, M.; Wilson, J.; Qian, M. Free radical scavenging properties of wheat extracts. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1619–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settanni, L.; Ventimiglia, G.; Alfonzo, A.; Corona, O.; Miceli, A.; Moschetti, G. An integrated technological approach to the selection of lactic acid bacteria of flour origin for sourdough production. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Z.; Hoseney, R.C. Development of an objective method for dough stickiness. LWT 1995, 28, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tock, C.; Gates, F.; Speirs, C.; Tucker, G.; Robbins, P.; Cox, P. A Method for measuring stickiness of bread dough. Annu. Trans. Nord. Rheol. Soc. 2013, 21, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Dobraszczyk, B.J.; Morgenstern, M.P. Rheology and breadmaking process. J. Cereal Sci. 2003, 38, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meullenet, J.F.; Lyon, B.G.; Carpenter, J.A.; Lyon, C.E. Relationship between sensory and instrumental texture profile attributes. J. Sens. Stud. 1998, 13, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speziale, M.; Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Mincione, A.; Carbonell-Barachina, A.A. Instrumental texture of torrone of Taurianova (Reggio Calabria, Southern Italy). Ital. J. Food Sci. 2010, 22, 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Nishinari, K.; Kohyama, K.; Kumagai, H.; Funami, T.; Bourne, M.C. Parameters of Texture Profile Analysis. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2013, 19, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, P.M.; Di Luccio, M.; Wüst Zibetti, A.; Zavair de Miranda, M.; de Francisco, A. Relationship between instrumental and sensory texture profile of bread loaves made with whole-wheat flour and fat replacer. J. Texture Stud. 2016, 47, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseney, R.C.; Smewing, J. Instrumental measurement of stickiness of doughs and other foods. J. Texture Stud. 1999, 30, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauvain, S.P. Breadmaking processes. In Technology of Breadmaking, 2nd ed.; Cauvain, S.P., Young, L.S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnewind, B.; Sliwinski, E.; Grolle, K.; Van Vliet, T. The Kieffer dough and gluten extensibility rig—An experimental evaluation. J. Texture Stud. 2003, 34, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesniak, A.S. Classification of textural characteristics. J. Food Sci. 1963, 28, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, M.J.; Hammes, W.P.; Gänzle, M.G. Effects of process parameters on growth and metabolism of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Candida humilis during rye sourdough fermentation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 218, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, I.; Aprodu, I. Studies concerning the use of Lactobacillus helveticus and Kluyveromyces marxianus for rye sourdough fermentation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 234, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicher, G. Baked goods. In Biotechnology; Rehm, H.J., Reed, G., Eds.; Verlag Chemie: Weinheim, Germany, 1983; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen, R.; Grosu-Tudor, S.; Mozzi, F.; Vaningelgem, F.; Zamfir, M.; de Valdez, G.F.; De Vuyst, L. Screening of lactic acid bacteria isolates from dairy and cereal products for exopolysaccharide production and genes involved. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 118, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siragusa, S.; Di Cagno, R.; Ercolini, D.; Minervini, F.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M. Taxonomic structure and monitoring of the dominant population of lactic acid bacteria during wheat flour sourdough type I propagation using Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis starters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbetti, M.; Corsetti, A. Lactobacillus sanfrancisco: A key sourdough lactic acid bacterium. Food Microbiol. 1997, 14, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, A.; Settanni, L. Lactobacilli in sourdough fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, M.L.L.; Scudeller Umeda, N.; Jackson, E.; Forsythe, S.J.; de Filippis, I. Isolation, molecular and phenotypic characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility of Cronobacter spp. from Brazilian retail foods. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.; Healy, B.; Negredo, C.; Anderson, W.; Fanning, S.; Iversen, C. Prevalence of Cronobacter species (Enterobacter sakazakii) in follow-on infant formulae and infant drinks. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 48, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhai, M.C.; Reij, M.W.; Gorris, L.G.M.; Guillaume-Gentil, O.; van Schothorst, M. Occurrence of Enterobacter sakazakii in food production environments and households. Lancet 2004, 363, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassem, M.A.A. Study of the micro-organisms associated with fermented bread (khamir) produced from sorghum in Gizan region, Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 86, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheirlinck, I.; Van der Meulen, R.; Van Schoor, A.; Vancanneyt, M.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P.; Huys, G. Taxonomic structure and stability of the bacterial community in Belgian sourdough ecosystems as assessed by culture and population fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kariluoto, S.; Aittamaa, M.; Korhola, M.; Salovaara, H.; Vahteristo, L.; Piironen, V. Effects of yeasts and bacteria on the levels of folates in rye sourdoughs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragaee, S.; Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M.; Noaman, M. Antioxidant activity and nutrient composition of selected cereals for food use. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E.; Rémésy, C. Is the in vitro antioxidant potential of whole-grain cereals and cereal products well reflected in vivo? J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-M.; Koh, B.-K. Antioxidant activity of hard wheat flour, dough and bread prepared using various processes with the addition of different phenolic acids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaee, S.; Guzar, I.; Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M.; Seetharaman, K. Bioactive components and antioxidant capacity of Ontario hard and soft wheat varieties. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthria, D.L.; Lu, Y.; John, K.M.M. Bioactive phytochemicals in wheat: Extraction, analysis, processing, and functional properties. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, F.; Dinelli, G.; Spisni, E.; Simonetti, E.; Trebbi, G.; Bosi, S.; Marotti, I. Phenolic acids of modern and ancient grains: Effect on in vitro cell model. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4075–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, K.K.; Sorrells, M.E.; Liu, R.H. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activity of wheat varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7825–7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, N.; Dahiya, S.; Kumar, S. Changes in polyphenol content of newly released varieties of wheat during different processing methods. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, P.; McKinnon, C.M. Effect of wheat variety, farming site, and bread-baking on total phenolics. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 41, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarter, N.; Liu, C.-S.; Sorrells, M.E.; Liu, R.H. Phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of six diverse varieties of whole wheat. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merike, V.; Matso, K.; Levandi, T.; Helmja, K.; Kaljurand, M. Phenolic compounds and the antioxidant activity of the bran, flour and whole grain of different wheat varieties. Procedia Chem. 2010, 2, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Nanguet, A.-L.; Beta, T. Comparison of antioxidant properties of refined and whole wheat flour and bread. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leváková, L.; Lacko-Bartošová, M. Phenolic acids and antioxidant activity of wheat species: A review. Agriculture 2017, 63, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Barros, L.; Fernandes, Â.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Callejo, M.J.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Morales, P.; Carrillo, J.M. Potential health claims of durum and bread wheat flours as functional ingredients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddomada, B.; Caretto, S.; Mita, G. Wheat bran phenolic acids: Bioavailability and stability in whole wheat-based foods. Molecules 2015, 20, 15666–15685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.S.; Joong-Ho, K.; Faqir, M.A.; Muhammad, S.; Farhan, S.; Muhammad, I.; Zaid, A.; Muhammad, N.; Shahzad, H. Wheat antioxidants, their role in bakery industry, and health perspective. In Wheat Improvement, Management and Utilization; Wanyera, R., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Zhou, J.; Wadhwa, S.S. Drinking yoghurts with berry polyphenols added before and after fermentation. Food Control 2013, 32, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nionelli, L.; Curri, N.; Curiel, J.A.; Di Cagno, R.; Pontonio, E.; Cavoski, I.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Exploitation of Albanian wheat cultivars: Characterization of the flours and lactic acid bacteria microbiota, and selection of starters for sourdough fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2014, 44, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripo, K.; Phianmongkhol, A.; Wirjantoro, T.I. Effect of inoculum levels and final pH values on the antioxidant properties of black glutinous rice solution fermented by Lactobacillus bulgaricus. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 2207–2213. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.-F.; Wise, M.L.; Gulvady, A.A.; Chang, T.; Kendra, D.F.; van Klinken, B.J.-W.; Shi, Y.; O’Shea, M. In vitro antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory activity of seven common oats. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruma, Z.; Tomsone, L.; Galoburda, R.; Straumite, E.; Kronberga, A.; Åssveen, M. Total phenols and antioxidant capacity of hull-less barley and hull-less oats. Agron. Res. 2016, 14, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Konopka, I.; Tańska, M.; Faron, A.; Czaplicki, S. Release of free ferulic acid and changes in antioxidant properties during the wheat and rye bread making process. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 23, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, V.; Bai, Y.; Gänzle, M.G. Metabolism of phenolic acids in whole wheat and rye malt sourdoughs. Food Microbiol. 2019, 77, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Nionelli, L.; Coda, R.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Use of sourdough fermented wheat germ for enhancing the nutritional, texture and sensory characteristics of the white bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 230, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhauer, M.G.; Haase, N.U.; Neumann, H.; Jansen, M. Antioxidant capacity of bread as a function of recipe and baking. Getreidetechnologie 2009, 63, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Karrar, E.M.A. A review on: Antioxidant and its impact during the bread making process. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 3, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulajová, A.; Kohajdová, Z.; Németh, K.; Hybenová, E. Phenolic contents, antioxidant properties, and sensory profiles of wheat round rolls supplemented with whole grain cereals. Acta Aliment. 2015, 44, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Viggiani, I.; Terracone, C.; Romaniello, R.; Del Nobile, M.A. Physical and sensory properties of bread enriched with phenolic aqueous extracts from vegetable wastes. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Casale, G.; Melini, V.; Maiani, G.; Acquistucci, R. Total polyphenol content and antioxidant properties of Solina (Triticum aestivum L.) and derivatives thereof. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2016, 28, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Andrade, C.; Morales, F.J. Unraveling the contribution of melanoidins to the antioxidant activity of coffee brews. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoza, V. Five years of research on health risks and benefits of Maillard reaction products: An update. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horszwald, A.; Troszynska, A.; del Castillo, M.D.; Zielinski, H. Protein profile and sensorial properties of rye breads. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Pinto, D.; Gobbetti, M. Selected lactic acid bacteria synthesize antioxidant peptides during sourdough fermentation of cereal flours. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Wang, L.; Huber, G.M.; Pitts, N.L. Effect of baking on dietary fibre and phenolics of muffins incorporated with apple skin powder. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A.S.; Waterhouse, D.S.; Quek, S.; Perera, C.O. Properties of bread dough with added fiber polysaccharides and phenolic antioxidants: A review. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, M.D.; Silvan, J.; Olza, J.; Gil, A.; del Castillo, M.D. Antioxidant properties of soy protein-fructooligosaccharide glycation systems and its hydrolyzates. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Howes, T.; Bhandari, B.R.; Truong, V. Stickiness in foods: A review of mechanisms and test methods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2001, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armero, E.; Collar, C. Texture properties of formulated wheat doughs. Relationships with dough and bread technological quality. Z. Lebensm Unters Forsch A 1997, 204, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, A.; Álvarez, A.; González, L.; Fernández, D.; Marcos, J.L.; Tornadijo, M.E. Effect of fermentation on microbiological, physicochemical and physical characteristics of sourdough and impact of its use on bread quality. Czech J. Food Sci. 2017, 35, 496–506. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Jha, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Upadhyay, A. Enhancement of the functionality of bread by incorporation of Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 2038–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sourdoughs | pH | TTA |

|---|---|---|

| SD m | 3.74 ± 0.02 f | 9.60 ± 0.05 a |

| PF7 | 5.55 ± 0.01 a | 2.75 ± 0.03 e |

| PF9 | 3.90 ± 0.07 e | 7.80 ± 0.04 b |

| PF7 F | 5.64 ± 0.07 a | 1.55 ± 0.02 f |

| PF9 F | 4.52 ± 0.03 b | 4.80 ± 0.05 d |

| PF7 M | 4.19 ± 0.03 c | 6.22 ± 0.04 c |

| PF9 M | 4.04 ± 0.02 d | 7.89 ± 0.05 b |

| Statistical significance | *** | *** |

| Samples | Organic Acids | QF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid (mg/g) | Acetic Acid (mg/g) | |||

| Dough | SD | 4.71 ± 0.09 a | 0.99 ± 0.01 b | 3.18 |

| SDC | 3.20 ± 0.08 b | 2.08 ± 0.05 a | 1.02 | |

| PF7 F | 0.44 ± 0.10 e | 0.46 ± 0.01 c | 0.64 | |

| PF7 M | 1.96 ± 0.04 d | 0.35 ± 0.00 d | 3.77 | |

| PF9 F | 3.25 ± 0.10 b | 0.46 ± 0.02 c | 4.70 | |

| PF9 M | 2.28 ± 0.06 c | 0.34 ± 0.03 d | 4.50 | |

| Bread | SD | 3.78 ± 0.04 A | 1.75 ± 0.09 B | - |

| SDC | 3.15 ± 0.06 B | 1.99 ± 0.11 A | - | |

| PF7 F | 0.35 ± 0.02 F | 0.27 ± 0.02 C | - | |

| PF7 M | 0.66 ± 0.02 E | 0.20 ± 0.02 C | - | |

| PF9 F | 1.02 ± 0.07 D | 0.32 ± 0.02 C | - | |

| PF9 M | 1.19 ± 0.03 C | 0.22 ± 0.03 C | - | |

| Statistical significance | *** | *** | ||

| Samples | DPPH a | Total Phenols b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 8 h | 21 h | 2 months | 0 h | 8 h | 21 h | 2 months | ||

| Sourdoughs | SD | 13.09 ± 0.07 c | 17.28 ± 0.08 b | 20.07 ± 0.16 a | 12.46 ± 0.22 d | 120.51 ± 0.54 e | 128.64 ± 0.47 d | 168.96 ± 0.24 c | 178.58 ± 0.19 b |

| SDC | 10.38 ± 0.18 e | 9.65 ± 0.03 f | 12.28 ± 0.17 d | 10.50 ± 0.19 e | 100.90 ± 0.23 h | 102.75 ± 0.21 g | 103.86 ± 0.13 f | 183.02 ± 0.25 a | |

| Statistical significance | *** | *** | |||||||

| Breads | SD | 26.55 ± 0.23 A | 80.56 ± 0.00 A | ||||||

| SDC | 24.69 ± 0.24 B | 72.79 ± 0.00 B | |||||||

| Statistical significance | *** | *** | |||||||

| Analyses | Sourdoughs | Breads | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF7 F | PF9 F | PF7 M | PF9 M | PF7 F | PF9 F | PF7 M | PF9 M | |

| DPPH a | 12.49 ± 0.12 c | 17.68 ± 0.24 a | 13.53 ± 0.26 b | 11.71 ± 0.20 d | 31.98 ± 0.14 B | 30.91 ± 0.25 C | 32.69 ± 0.27 A | 24.04 ± 0.36 D |

| Statistical significance | *** | *** | ||||||

| Total phenols b | 19.53 ± 0.04 d | 30.63 ± 0.34 b | 52.82 ± 0.17 a | 26.19 ± 0.08 c | 18.05 ± 0.11 B | 15.09 ± 0.09 C | 25.82 ± 0.13 A | 11.76 ± 0.10 D |

| Statistical significance | *** | *** | ||||||

| Sourdough | Stickiness Test | Penetration Test | |||

| Stickiness (g) | Work of Adhesion (g·s) | Dough Strength/Cohesiveness (mm) | Hardness (g) | ||

| SD | 111.82 ± 3.92 a | 19.22 ± 0.50 a | 6.37 ± 0.04 a | 46.37 ± 3.87 a | |

| SDC | 114.40 ± 2.80 a | 16.82 ± 1.21 a | 6.31 ± 0.08 a | 42.06 ± 2.71 a | |

| (a) | |||||

| Sourdough | Warburtons Test | Kieffer Test | |||

| Firmness (kg) | Work of Compression (kg·s) | Adhesiveness Peak (kg) | Resistance to Extensibility (g) | Extensibility (mm) | |

| SD | 0.59 ± 0.14 a | 4.19 ± 0.62 a | 0.75 ± 0.14 a | 6.48 ± 0.43 a | 0.23 ± 0.30 a |

| SDC | 0.47 ± 0.06 a | 3.33 ± 0.56 a | 0.60 ± 0.05 a | 5.22 ± 0.39 b | 0.19 ± 0.28 a |

| (b) | |||||

| Sourdough | Stickiness Test | Penetration Test | |||

| Stickiness (g) | Work of Adhesion (g·s) | Dough Strength/Cohesiveness (mm) | Hardness (g) | ||

| Mother sourdough (PF7 + SD m) | 37.98 ± 1.87 b | 3.43 ± 0.54 a | 1.62 ± 0.33 a | 150.23 ± 26.25 a | |

| Mother sourdough (PF9 + SD m) | 79.58 ± 13.46 ab | 4.33 ± 1.44 a | 1.24 ± 0.48 a | 133.65 ± 14.44 ab | |

| PF7 F | 72.70 ± 10.64 ab | 5.94 ± 2.20 a | 1.87 ± 0.51 a | 62.73 ± 15.67 b | |

| PF9 F | 99.52 ± 14.26 a | 7.50 ± 1.85 a | 1.87 ± 0.39 a | 88.46 ± 14.86 ab | |

| PF7 M | 76.29 ± 16.82 ab | 5.31 ± 2.01 a | 1.70 ± 0.56 a | 96.00 ± 13.46 ab | |

| PF9 M | 105.49 ± 11.12 a | 9.22 ± 2.32 a | 2.34 ± 0.66 a | 75.79 ± 22.03 ab | |

| (a) | |||||

| Sourdough | Warburtons Test | Kieffer Test | |||

| Firmness (kg) | Work of Compression (kg·s) | Adhesiveness Peak (kg) | Resistance to Extensibility (g) | Extensibility (mm) | |

| Mother sourdough (PF7 + SDm) | 3.38 ± 0.38 a | 19.04 ± 4.99 a | −0.73 ± 0.11 a | 33.96 ± 7.49 a | 35.94 ± 1.72 ab |

| Mother sourdough (PF9 + SDm) | 1.38 ± 0.23 a | 11.13 ± 1.79 a | −1.62 ± 0.28 a | 7.94 ± 1.96 a | 24.70 ± 3.84 b |

| PF7 F | 2.98 ± 1.30 a | 10.86 ± 3.80 a | −1.08 ± 0.31 a | 39.95 ± 8.44 a | 40.06 ± 4.07 a |

| PF9 F | 3.34 ± 0.85 a | 14.16 ± 3.26 a | −1.13 ± 0.15 a | 28.49 ± 11.64 a | 37.73 ± 2.26 a |

| PF7 M | 4.38 ± 0.89 a | 16.46 ± 3.55 a | −0.92 ± 0.10 a | 30.20 ± 8.23 a | 36.23 ± 1.68 ab |

| PF9 M | 2.13 ± 1.56 a | 10.94 ± 8.65 a | −0.92 ± 0.65 a | 24.84 ± 5.89 a | 36.68 ± 3.45 ab |

| (b) | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sidari, R.; Martorana, A.; Zappia, C.; Mincione, A.; Giuffrè, A.M. Persistence and Effect of a Multistrain Starter Culture on Antioxidant and Rheological Properties of Novel Wheat Sourdoughs and Bread. Foods 2020, 9, 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091258

Sidari R, Martorana A, Zappia C, Mincione A, Giuffrè AM. Persistence and Effect of a Multistrain Starter Culture on Antioxidant and Rheological Properties of Novel Wheat Sourdoughs and Bread. Foods. 2020; 9(9):1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091258

Chicago/Turabian StyleSidari, Rossana, Alessandra Martorana, Clotilde Zappia, Antonio Mincione, and Angelo Maria Giuffrè. 2020. "Persistence and Effect of a Multistrain Starter Culture on Antioxidant and Rheological Properties of Novel Wheat Sourdoughs and Bread" Foods 9, no. 9: 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091258

APA StyleSidari, R., Martorana, A., Zappia, C., Mincione, A., & Giuffrè, A. M. (2020). Persistence and Effect of a Multistrain Starter Culture on Antioxidant and Rheological Properties of Novel Wheat Sourdoughs and Bread. Foods, 9(9), 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091258