Changes in the Physical Properties of Calcium Alginate Gel Beads under a Wide Range of Gelation Temperature Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

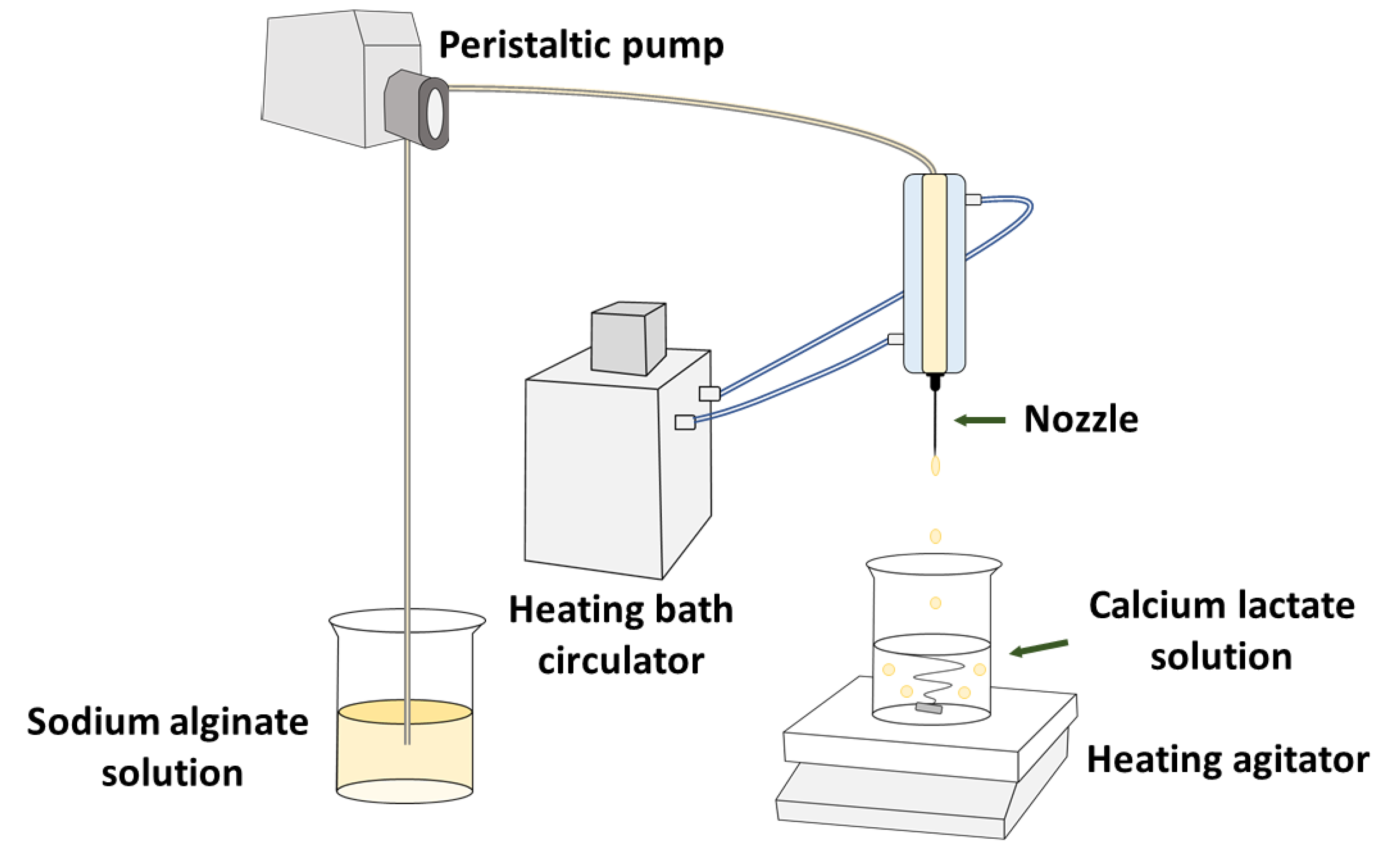

2.2. Calcium Alginate Gel (CAG) Bead Preparation Method

2.3. Diameter and Sphericity Measurement

2.4. Rupture Strength Measurement

2.5. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Moisture Content

2.7. Calcium and Sodium Ion Content

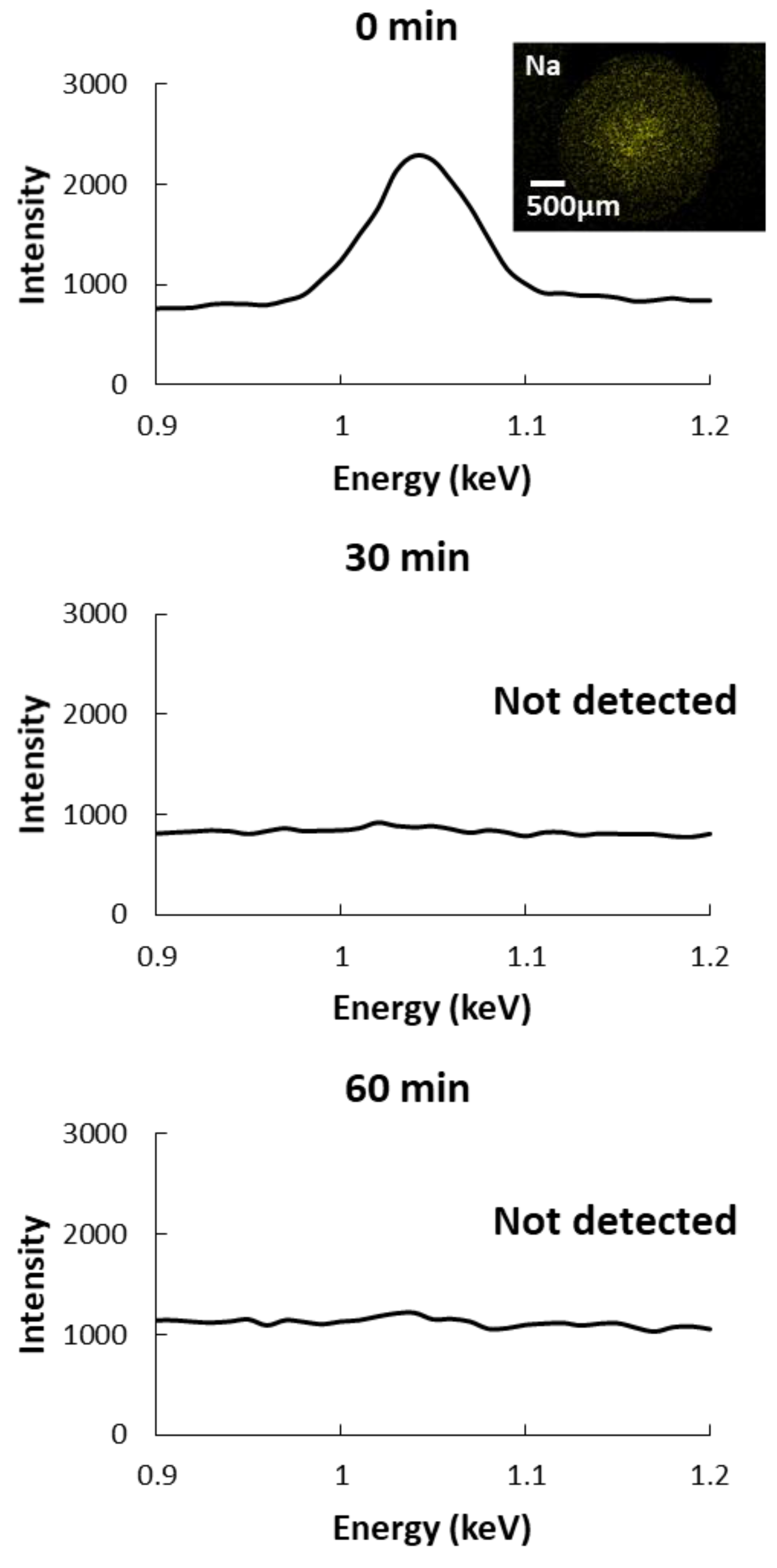

2.8. Sodium Ions Diffusion of CAG Beads

2.9. CAG Bead Microstructure

2.10. Density

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fitting the Models

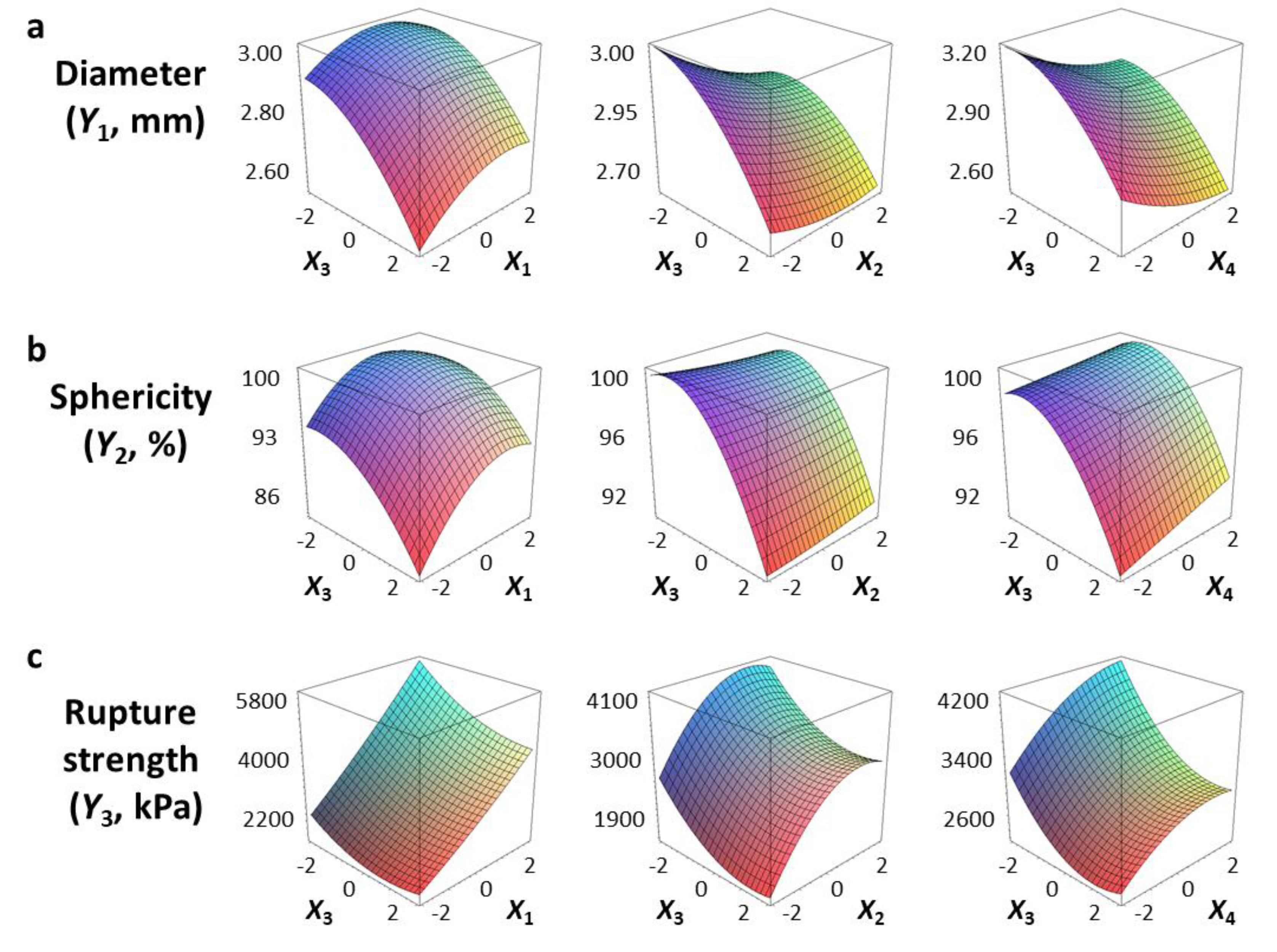

3.2. Diameter and Sphericity

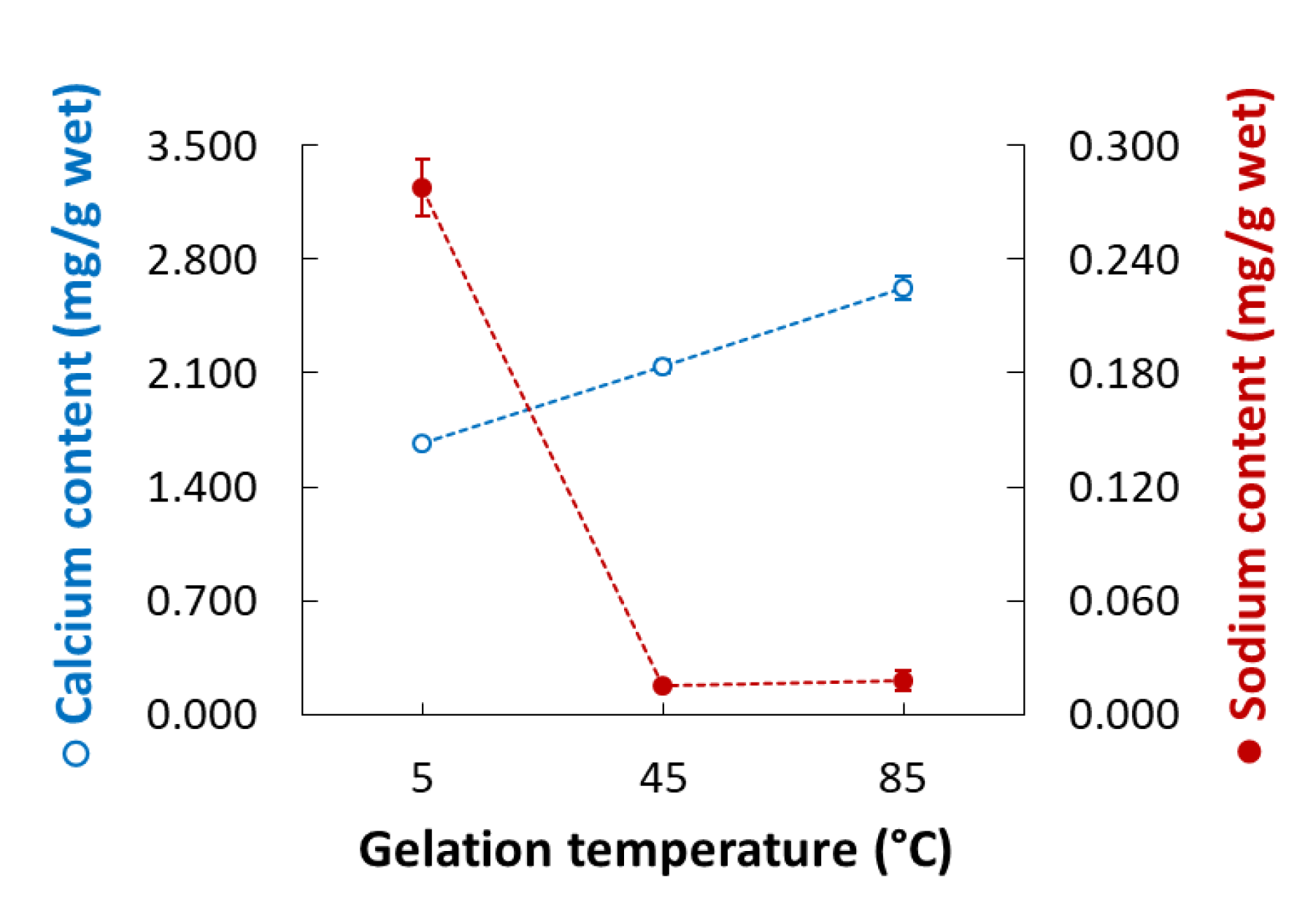

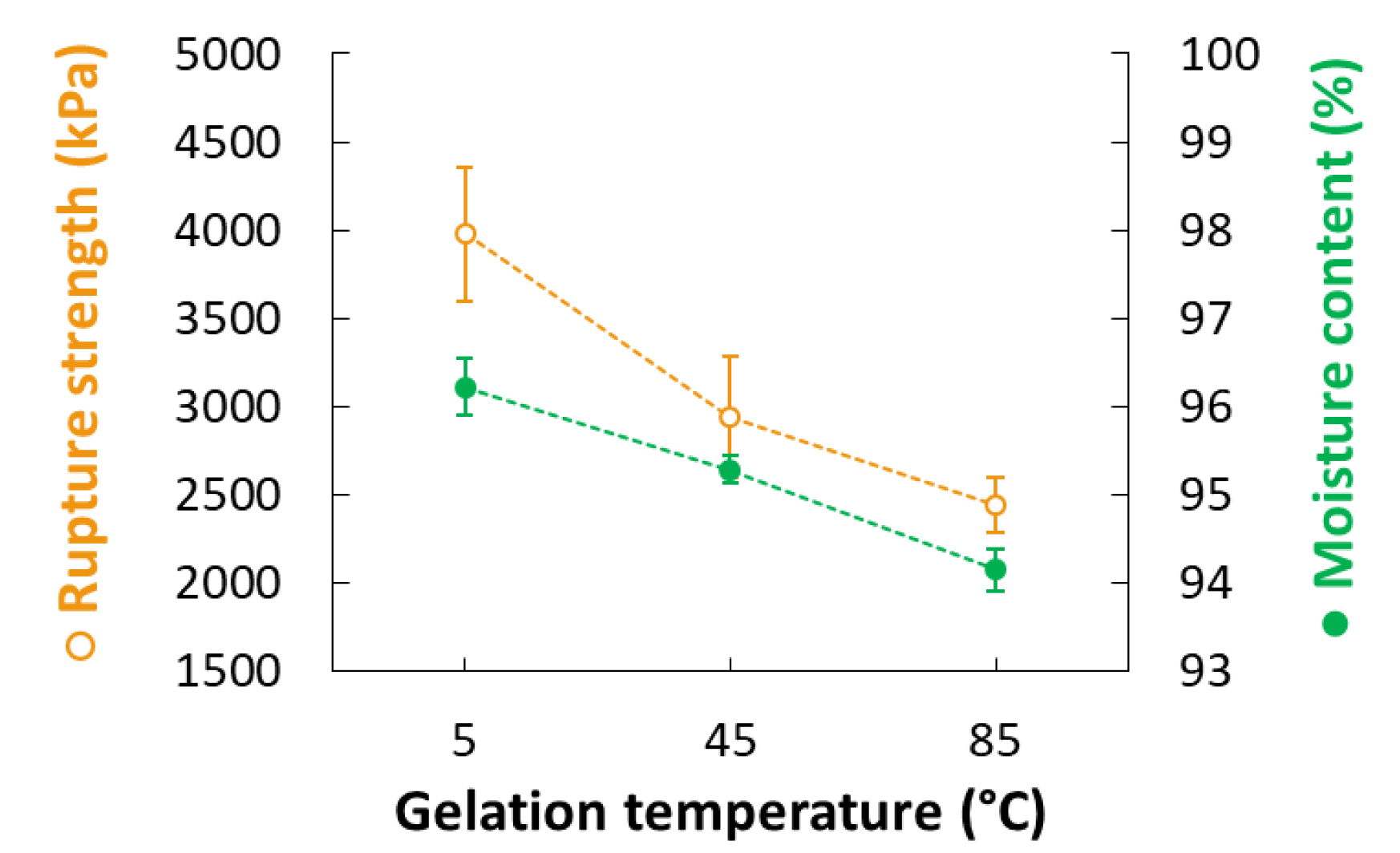

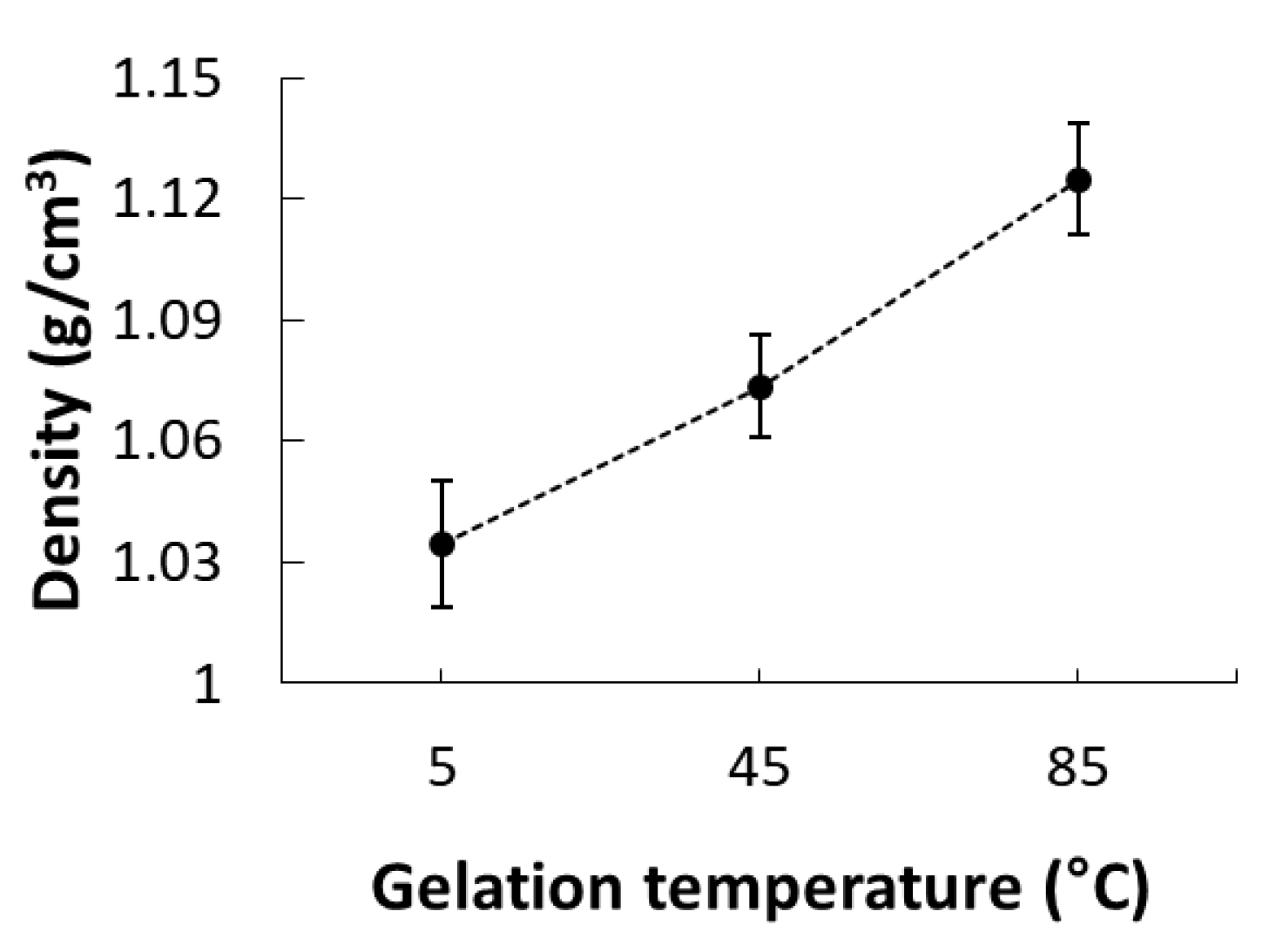

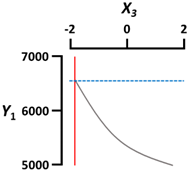

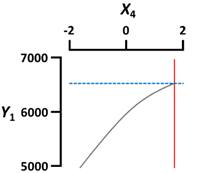

3.3. Rupture Strength

3.4. Microstructure

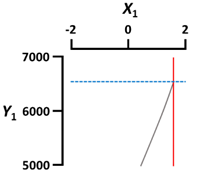

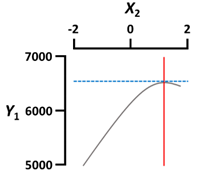

3.5. Optimal Conditions for Maximum Rupture Strength

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vargas, P.O.; Pereira, N.R.; Guimarães, A.O.; Waldman, W.R.; Pereira, V.R. Shrinkage and Deformation during Convective Drying of Calcium Alginate. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 97, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli-Kafrani, E.; Shekarchizadeh, H.; Masoudpour-Behabadi, M. Development of Edible Films and Coatings from Alginates and Carrageenans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 137, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Cocco, M.E.; Bianchetti, C.; Chiellini, F. 1H NMR Studies of Alginate Interactions with Amino Acids. Journal of bioactive and compatible polymers. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2003, 18, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasdalen, H.; Larsen, B.; Smidsrød, O. A pmr study of the composition and sequence of uronate residues in alginates. Carbohydr. Res. 1979, 68, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Park, H.J. Calcium-alginate beads loaded with gallic acid: Preparation and characterization. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemmer, M.; Patel, A.V. Review of encapsulation methods suitable for microbial biological control agents. Biol. Control 2013, 67, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, B.B.; Jo, E.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, S.B. Production Optimization of Flying Fish Roe Analogs Using Calcium Alginate Hydrogel Beads. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, M.; Du, Y.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Control of lipase digestibility of emulsified lipids by encapsulation within calcium alginate beads. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.B.; Ravindra, P.; Chan, E.S. Size and shape of calcium alginate beads produced by extrusion dripping. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2013, 36, 1627–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voo, W.P.; Ooi, C.W.; Islam, A.; Tey, B.T.; Chan, E.S. Calcium alginate hydrogel beads with high stiffness and extended dissolution behaviour. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Shen, N.; Yuan, C.; Hu, Y. Preparation and characterization of calcium alginate-chitosan complexes loaded with lysozyme. J. Food Eng. 2018, 233, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.J.; Marques, A.M.; Pastrana, L.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Sillankorva, S.M.; Cerqueira, M.A. Physicochemical properties of alginate-based films: Effect of ionic crosslinking and mannuronic and guluronic acid ratio. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, M.; Tagawa, Y.; Tominaga, M. The texture and preference of “mentsuyu (Japanese noodle soup base) caviar” prepared from sodium alginate and calcium lactate. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagiwa, K.; Kozawa, T.; Ohkawa, A. Effects of alginate composition and gelling conditions on diffusional and mechanical properties of calcium-alginate gel beads. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1995, 28, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Kennedy, J.F. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of polysaccharides production parameters from the roots of Codonopsis pilosula by a central composite design. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, C.; Cho, S.; Kim, S.B. Effects of Thermal Treatment on the Physical Properties of Edible Calcium Alginate Gel Beads: Response Surface Methodological Approach. Foods 2019, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadiyan, P.; Hemmateenejad, B. Multi-response optimization of factors affecting ultrasonic assisted extraction from Iranian basil using central composite design. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, A.; Sahan, T.; Cogenli, M.S.; Yurtcan, A.B.; Aktas, N.; Kivrak, H. A novel Central Composite Design based response surface methodology optimization study for the synthesis of Pd/CNT direct formic acid fuel cell anode catalyst. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 11002–11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.M.; Gu, Y.S.; Kim, S.B. Extracting Optimization and Physical Properties of Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares) Skin Gelatin Compared to Mammalian Gelatins. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, A.M.; May, A.T. Product excellence through design of experiments. Cereal Foods World 1987, 32, 857. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.N.; Nie, H.L.; Zhu, L.M.; Chen, T.X. Optimization of adsorption conditions of papain on dye affinity membrane using response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2336–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashtjin, A.M.; Abbasi, S. Nano-emulsification of orange peel essential oil using sonication and native gums. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Santelli, R.E.; Oliveira, E.P.; Villar, L.S.; Escaleira, L.A. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) as a Tool for Optimization in Analytical Chemistry. Talanta 2008, 76, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzir, M.H.; Abbasiliasi, S.; Ariff, A.B.; Yusoff, S.B.; Ng, H.S.; Tan, J.S. Partitioning behavior of recombinant lipase in Escherichia coli by ionic liquid-based aqueous two-phase systems. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 82571–82580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florián-Algarín, V.; Acevedo, A. Rheology and thermotropic gelation of aqueous sodium alginate solutions. J. Pharm. Innov. 2010, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klokk, T.I.; Melvik, J.E. Controlling the size of alginate gel beads by use of a high electrostatic potential. J. Microencapsul. 2002, 19, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Hou, L.D.; Li, Z.; Zheng, W.; Li, L. Study on shape optimization of calcium–alginate beads. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 648, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklamani, G.; Cheneler, D.; Grover, L.M.; Adams, M.J.; Bowen, J. Mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels manufactured using external gelation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 36, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, E.J.; De Piante Vicín, D.A.; Rubiolo, A.C. Evaluation of stress-strain for characterization of the rheological behavior of alginate and carrageenan gels. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2002, 19, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdhan, T.; Ching, S.H.; Prakash, S.; Bhandari, B. Time dependent gelling properties of cuboid alginate gels made by external gelation method: Effects of alginate-CaCl2 solution ratios and pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 90, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augst, A.D.; Kong, H.J.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 2006, 6, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, J.L.; Dennis, R.G.; Mooney, D.J. The tensile properties of alginate hydrogels. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3187–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.K.; Ma, P.X. Ionically crosslinked alginate hydrogels as scaffolds for tissue engineering: Part 1. Structure, gelation rate and mechanical properties. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.K.; Sharma, S. Investigation of swelling/degradation behaviour of alginate beads crosslinked with Ca2+ and Ba2+ ions. React. Funct. Polym. 2004, 59, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, A.; Skjåk-Bræk, G.; Smidsrød, O. Alginate as immobilization material: I. Correlation between chemical and physical properties of alginate gel beads. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989, 33, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayarza, J.; Coello, Y.; Nakamatsu, J. SEM–EDS study of ionically cross-linked alginate and alginic acid bead formation. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2017, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Henke, A.; Richtering, W.; Groll, J. Magnesium ions and alginate do form hydrogels: A rheological study. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 4877–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Yan, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, Y. Simulation and optimization of continuous laser transmission welding between PET and titanium through FEM, RSM, GA and experiments. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2013, 51, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent Variables | Symbol | Range and Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Sodium alginate concentration (%, w/v) | X1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Calcium lactate concentration (%, w/v) | X2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| Gelation temperature (°C) | X3 | 5 | 25 | 45 | 65 | 85 |

| Gelation time (min) | X4 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 |

| Run No. | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded Values | Uncoded Values | |||||||||||

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | ||

| Factorial | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 25 | 12 | 3.07 | 96.7 | 1993 |

| portions | 2 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 25 | 12 | 3.08 | 98.9 | 3473 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 25 | 12 | 3.00 | 96.2 | 2274 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 25 | 12 | 3.02 | 98.1 | 4005 | |

| 5 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 65 | 12 | 2.82 | 92.1 | 1901 | |

| 6 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 65 | 12 | 2.88 | 95.4 | 2629 | |

| 7 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 65 | 12 | 2.81 | 91.6 | 2195 | |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 65 | 12 | 2.87 | 95.7 | 3606 | |

| 9 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 25 | 24 | 2.93 | 97.8 | 2420 | |

| 10 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 25 | 24 | 2.99 | 99.2 | 3832 | |

| 11 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 25 | 24 | 2.91 | 98.3 | 2601 | |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 25 | 24 | 2.91 | 97.8 | 4500 | |

| 13 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 65 | 24 | 2.72 | 94.6 | 1959 | |

| 14 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 65 | 24 | 2.77 | 95.5 | 3575 | |

| 15 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 65 | 24 | 2.70 | 94.2 | 2087 | |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 65 | 24 | 2.77 | 95.4 | 3902 | |

| Axial | 17 | −2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.73 | 89.4 | 1436 |

| portions | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.99 | 98.5 | 4420 |

| 19 | 0 | −2 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 45 | 18 | 3.14 | 96.6 | 1044 | |

| 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.82 | 98.1 | 3414 | |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 5 | 18 | 3.04 | 98.1 | 3976 | |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 85 | 18 | 2.62 | 90.7 | 2440 | |

| 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 45 | 6 | 3.09 | 96.7 | 2065 | |

| 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 45 | 30 | 2.88 | 97.8 | 3111 | |

| Center | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.97 | 98.3 | 2788 |

| points | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.92 | 96.6 | 2942 |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 45 | 18 | 2.88 | 97.5 | 3110 | |

| Parameter | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | |

| Constant | 2.92333 | 0.001 | 97.4667 | 0.001 | 2946.67 | 0.001 |

| X1 | 0.03542 | 0.011 | 1.3625 | 0.001 | 752.50 | 0.001 |

| X2 | −0.03792 | 0.007 | 0.0042 | 0.986 | 338.67 | 0.001 |

| X3 | −0.10042 | 0.001 | −1.8042 | 0.001 | −263.17 | 0.003 |

| X4 | −0.05292 | 0.001 | 0.4292 | 0.088 | 203.83 | 0.013 |

| X1X1 | −0.01969 | 0.141 | −0.8198 | 0.006 | 28.04 | 0.713 |

| X2X2 | 0.01031 | 0.426 | 0.0302 | 0.904 | −146.71 | 0.072 |

| X3X3 | −0.02719 | 0.050 | −0.7073 | 0.014 | 98.04 | 0.212 |

| X4X4 | 0.01156 | 0.373 | 0.0052 | 0.983 | −56.96 | 0.459 |

| X1X2 | −0.00188 | 0.899 | −0.0688 | 0.812 | 101.25 | 0.262 |

| X1X3 | 0.00937 | 0.528 | 0.2813 | 0.340 | −59.50 | 0.502 |

| X1X4 | 0.00187 | 0.899 | −0.5313 | 0.085 | 87.00 | 0.331 |

| X2X3 | 0.01188 | 0.427 | 0.0938 | 0.746 | 4.00 | 0.964 |

| X2X4 | 0.00187 | 0.899 | 0.0063 | 0.983 | −48.75 | 0.581 |

| X3X4 | 0.00063 | 0.966 | 0.1063 | 0.714 | −26.00 | 0.767 |

| Quadratic Polynomial Model Equations | R2 | Adj R2 | S | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 = 2.92333 + 0.03542X1 − 0.03792X2 − 0.10042X3 − 0.05292X4 − 0.01969X12 + 0.01031X22 − 0.02719X32 + 0.01156X42 − 0.00188X1X2 + 0.00937X1X3 + 0.00187X1X4 + 0.01188X2X3 + 0.00187X2X4 + 0.00062X3X4 | 0.913 | 0.811 | 0.0577410 | 0.001 |

| Y2 = 97.4667 + 1.3625X1 + 0.0042X2 − 1.8042X3 + 0.4292X4 − 0.8198X12 + 0.0302X22 − 0.7073X32 + 0.0052X42 − 0.0688X1X2 + 0.2813X1X3 − 0.5313X1X4 + 0.0938X2X3 + 0.0063X2X4 + 0.1063X3X4 | 0.912 | 0.809 | 1.13336 | 0.001 |

| Y3 = 2946.67 + 752.50X1 + 338.67X2 − 263.17X3 + 203.83X4 + 28.04X12 − 146.71X22 + 98.04X32 − 56.96X42 + 101.25X1X2 − 59.50X1X3 + 87.00X1X4 + 4.00X2X3 − 48.75X2X4 − 26.00X3X4 | 0.935 | 0.860 | 343.729 | 0.001 |

| Dependent Variables | Sources | DF | SS | MS | f-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 Diameter (mm) | Regression | |||||

| Linear | 4 | 0.373817 | 0.093454 | 28.03 | 0.001 | |

| Square | 4 | 0.040404 | 0.010101 | 3.03 | 0.061 | |

| Interaction | 6 | 0.003838 | 0.000640 | 0.19 | 0.973 | |

| Residual | ||||||

| Lack of fit | 10 | 0.035942 | 0.003594 | 1.77 | 0.415 | |

| Pure error | 2 | 0.004067 | 0.002033 | - | - | |

| Total | 26 | 0.458067 | - | - | - | |

| Y2 Sphericity (%) | Regression | |||||

| Linear | 4 | 127.095 | 31.7738 | 24.74 | 0.001 | |

| Square | 4 | 25.677 | 6.4193 | 5.00 | 0.013 | |

| Interaction | 6 | 6.179 | 1.0298 | 0.80 | 0.587 | |

| Residual | ||||||

| Lack of fit | 10 | 13.967 | 1.3967 | 1.93 | 0.389 | |

| Pure error | 2 | 1.447 | 0.7233 | - | - | |

| Total | 26 | 174.365 | - | - | - | |

| Y3 Rupture strength (kPa) | Regression | |||||

| Linear | 4 | 19,002,146 | 4,750,537 | 40.21 | 0.001 | |

| Square | 4 | 1,093,213 | 273,303 | 2.31 | 0.117 | |

| Interaction | 6 | 390,870 | 65,145 | 0.55 | 0.760 | |

| Residual | ||||||

| Lack of fit | 10 | 1,365,918 | 136,592 | 5.27 | 0.170 | |

| Pure error | 2 | 51,875 | 25,937 | - | - | |

| Total | 26 | 21,904,022 | - | - | - | |

| Immersion Time | 0 min | 30 min | 60 min |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rupture strength | 3910 ± 150 a | 3784 ± 119 a | 3187 ± 114 b |

| Optimal Conditions | Y3 Rupture Strength (kPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Value | Maximum | |||

| X1 Sodium alginate concentration (%, w/v) | Coded value | 2 |  | |

| Actual value | 3.6 | |||

| X2 Calcium lactate concentration (%, w/v) | Coded value | 1.5 |  | |

| Actual value | 4 | |||

| X3 Gelation temperature (°C) | Coded value | −2 |  | |

| Actual value | 4 | |||

| X4 Gelation time (min) | Coded value | 2 |  | |

| Actual value | 30 | |||

| Y1 Diameter (mm) | Y2 Sphericity (%) | Y3 Rupture Strength (kPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted values | 2.85 | 94.5 | 6676 |

| Experimental values | 2.88 ± 0.01 | 97.5 ± 0.9 | 6444 ± 692 |

| Error (%) | 1.05 | 3.17 | 3.48 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, C.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.; Cho, S.; Kim, S.-B. Changes in the Physical Properties of Calcium Alginate Gel Beads under a Wide Range of Gelation Temperature Conditions. Foods 2020, 9, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9020180

Jeong C, Kim S, Lee C, Cho S, Kim S-B. Changes in the Physical Properties of Calcium Alginate Gel Beads under a Wide Range of Gelation Temperature Conditions. Foods. 2020; 9(2):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9020180

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Chungeun, Seonghui Kim, Chanmin Lee, Suengmok Cho, and Seon-Bong Kim. 2020. "Changes in the Physical Properties of Calcium Alginate Gel Beads under a Wide Range of Gelation Temperature Conditions" Foods 9, no. 2: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9020180

APA StyleJeong, C., Kim, S., Lee, C., Cho, S., & Kim, S.-B. (2020). Changes in the Physical Properties of Calcium Alginate Gel Beads under a Wide Range of Gelation Temperature Conditions. Foods, 9(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9020180