Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe)

Abstract

1. Introduction

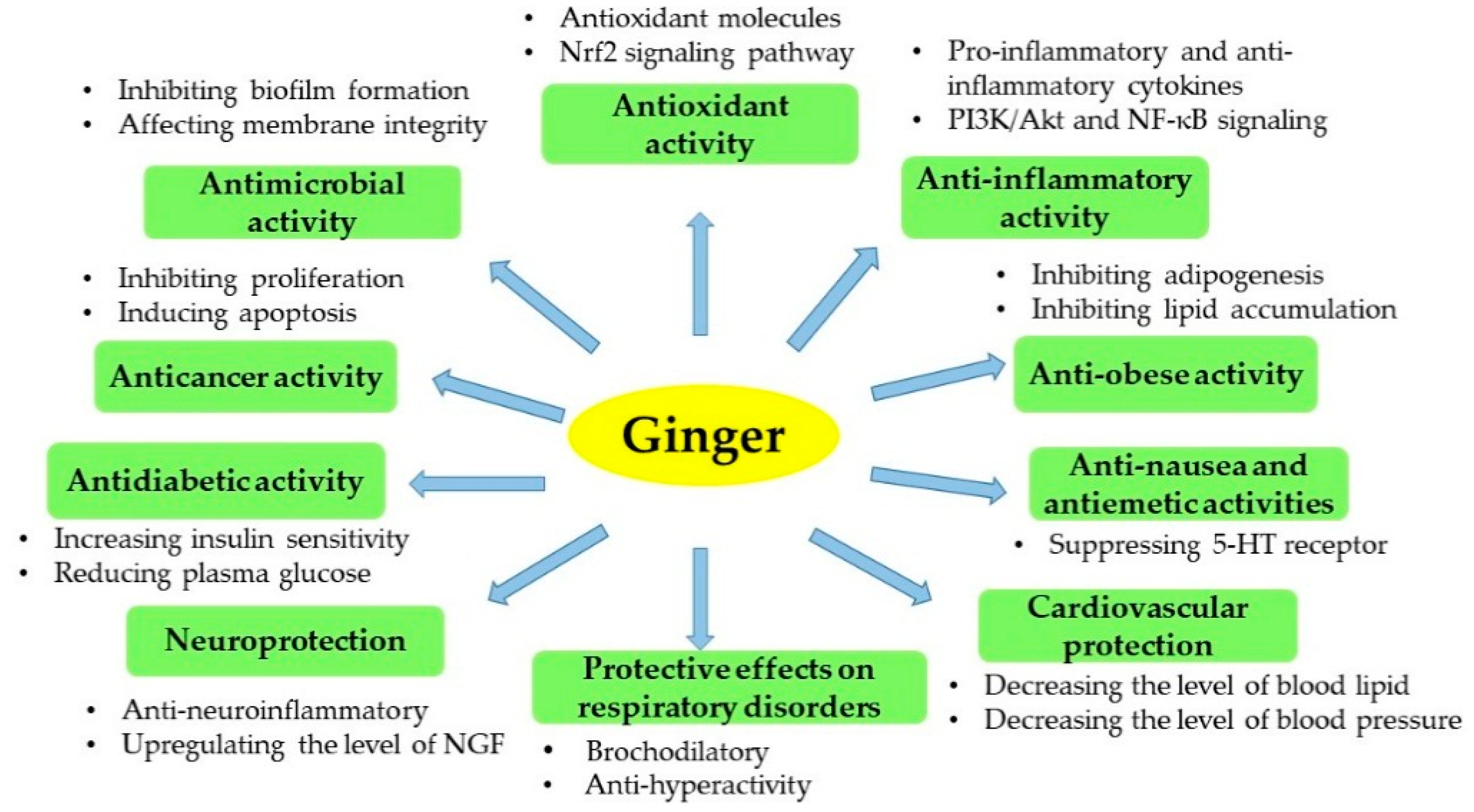

2. Bioactive Components and Bioactivities of Ginger

2.1. Bioactive Components

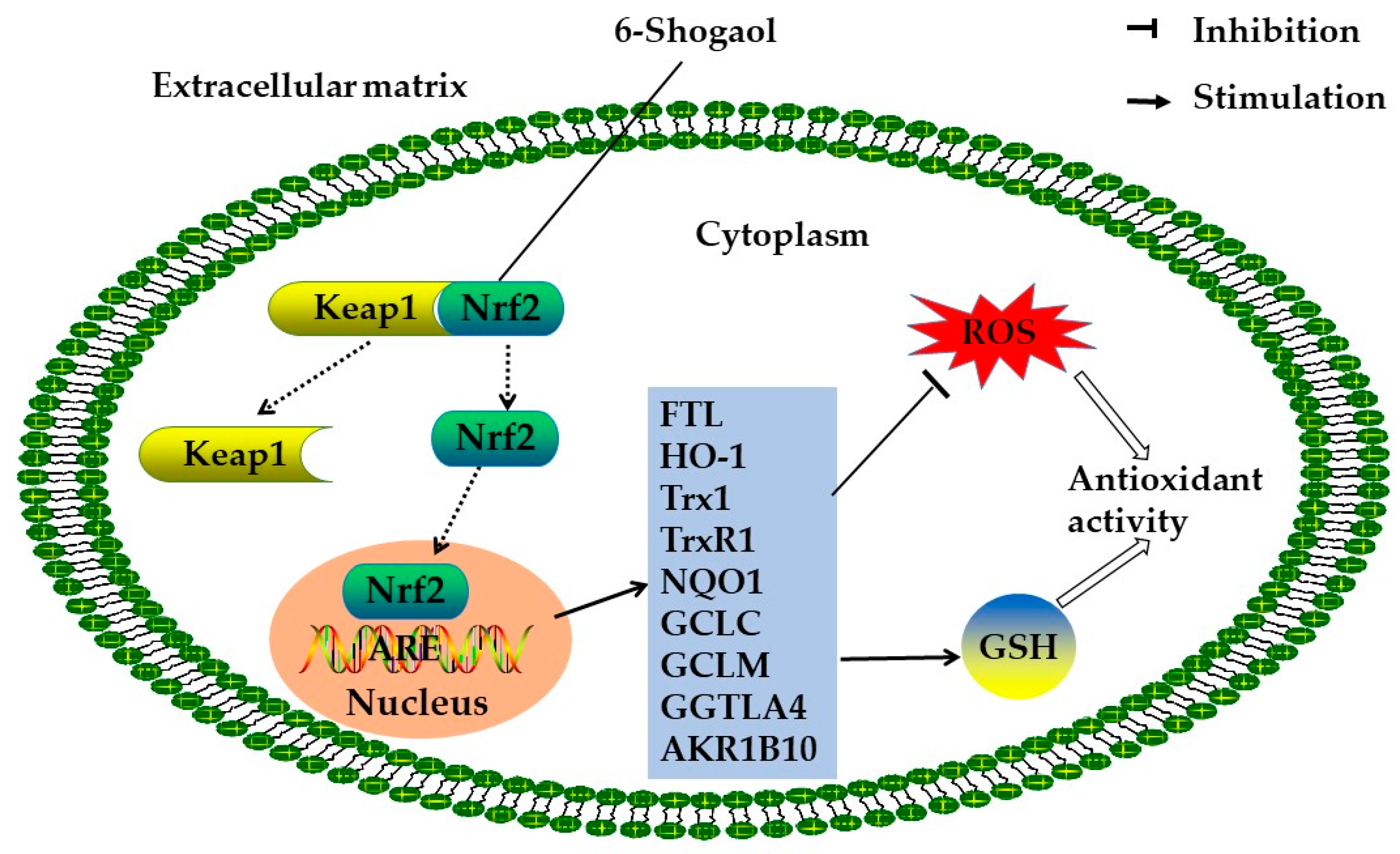

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

2.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

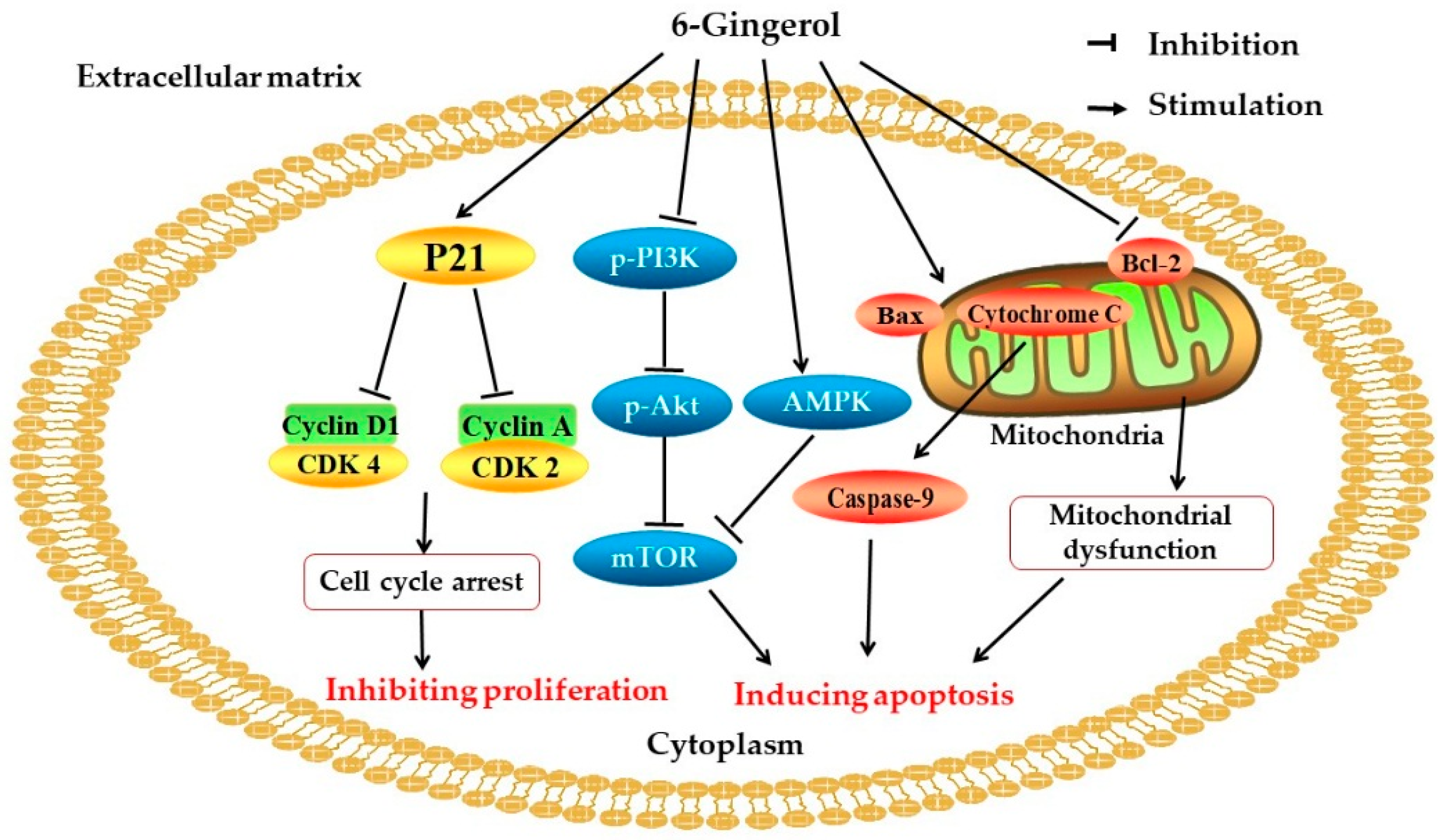

2.5. Cytotoxicity

2.6. Neuroprotection

2.7. Cardiovascular Protection

2.8. Antiobesity Activity

2.9. Antidiabetic Activity

2.10. Antinausea and Antiemetic Activities

2.11. Protective Effects against Respiratory Disorders

2.12. Other Bioactivities of Ginger

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, Y.A.; Song, C.W.; Koh, W.S.; Yon, G.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, K.H. Anti-inflammatory effects of the Zingiber officinale Roscoe constituent 12-dehydrogingerdione in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated raw 264.7 cells. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, G.D. Ginger: Is it ready for prime time? Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Park, S.W. Chromatographic analysis, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of ginger extracts and its reference compounds. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 70, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Viennois, E.; Prasad, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Han, M.K.; Xiao, B.; Xu, C.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. Edible ginger-derived nanoparticles: A novel therapeutic approach for the prevention and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated cancer. Biomaterials 2016, 101, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.V.; Murthy, P.S.; Manjunatha, J.R.; Bettadaiah, B.K. Synthesis and quorum sensing inhibitory activity of key phenolic compounds of ginger and their derivatives. Food Chem. 2014, 159, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citronberg, J.; Bostick, R.; Ahearn, T.; Turgeon, D.K.; Ruffin, M.T.; Djuric, Z.; Sen, A.; Brenner, D.E.; Zick, S.M. Effects of ginger supplementation on cell-cycle biomarkers in the normal-appearing colonic mucosa of patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer: Results from a pilot, randomized, and controlled trial. Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.; Chang, K.; Lin, C. Anti-neuroinflammatory capacity of fresh ginger is attributed mainly to 10-gingerol. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3183–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, A.J.; Thome, G.R.; Morsch, V.M.; Stefanello, N.; Goularte, J.F.; Bello-Klein, A.; Oboh, G.; Chitolina Schetinger, M.R. Effect of dietary supplementation of ginger and turmeric rhizomes on angiotensin-1 converting enzyme (ACE) and arginase activities in L-NAME induced hypertensive rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, S.; Kwon, G.T.; Lee, E.; Jang, W.J.; Yang, H.; Kim, J.H.; Thimmegowda, N.R.; Chung, M.; Kwon, J.Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Gingerenone A, a polyphenol present in ginger, suppresses obesity and adipose tissue inflammation in high-fat diet-fed mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Tsai, Y.; Korinek, M.; Hung, P.; El-Shazly, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hsieh, T.; Chang, F. 6-Paradol and 6-shogaol, the pungent compounds of ginger, promote glucose utilization in adipocytes and myotubes, and 6-paradol reduces blood glucose in high-fat diet-fed mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walstab, J.; Krueger, D.; Stark, T.; Hofmann, T.; Demir, I.E.; Ceyhan, G.O.; Feistel, B.; Schemann, M.; Niesler, B. Ginger and its pungent constituents non-competitively inhibit activation of human recombinant and native 5-HT3 receptors of enteric neurons. Neurogastroent. Motil. 2013, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.A.; Siviski, M.E.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Hoonjan, B.; Emala, C.W. Effects of ginger and its constituents on airway smooth muscle relaxation and calcium regulation. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. 2013, 48, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Ginger and its constituents: role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroent. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 142979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Fang, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Q.; Shi, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Du, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Ginger oleoresin alleviated gamma-ray irradiation-induced reactive oxygen species via the Nrf2 protective response in human mesenchymal stem cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1480294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadich, E.; Hlavac, J.; Volna, T.; Varanasi, L.; Hajduch, M.; Dzubak, P. Effects of ginger phenylpropanoids and quercetin on Nrf2-ARE pathway in human BJ fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2173275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.; Chuang, C.; Chen, H.; Wan, C.; Chen, T.; Lin, L. Bioactive components analysis of two various gingers (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and antioxidant effect of ginger extracts. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poprac, P.; Jomova, K.; Simunkova, M.; Kollar, V.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Targeting free radicals in oxidative stress-related human diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Gan, R.; Song, F.; Kuang, L.; Li, H. Antioxidant capacities and total phenolic contents of infusions from 223 medicinal plants. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Lin, X.; Xu, X.; Gao, L.; Xie, J.; Li, H. Antioxidant capacities and total phenolic contents of 56 vegetables. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Xu, X.; Guo, Y.; Xia, E.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Chen, F.; Ling, W.; Li, H. Determination of antioxidant property and their lipophilic and hydrophilic phenolic contents in cereal grains. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.; Gan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Xia, E.; Li, H. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of herbal and tea infusions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, X.; Gan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, E.; Li, H. Antioxidant capacities and total phenolic contents of 62 fruits. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Deng, G.; Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Li, S.; Xia, E.; Li, F.; Chen, F.; Ling, W.; Li, H. Antioxidant capacities, phenolic compounds and polysaccharide contents of 49 edible macro-fungi. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Gan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Kuang, L.; Li, H. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of selected chinese medicinal plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2362–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolaji, A.O.; Ojo, M.; Afolabi, T.T.; Arowoogun, M.D.; Nwawolor, D.; Farombi, E.O. Protective properties of 6-gingerol-rich fraction from Zingiber officinale (ginger) on chlorpyrifos-induced oxidative damage and inflammation in the brain, ovary and uterus of rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 270, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hong, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, L. Chemical characterization and antioxidant activities comparison in fresh, dried, stir-frying and carbonized ginger. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1011, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakulnarmrat, K.; Srzednicki, G.; Konczak, I. Antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory and antiproliferative activity of polyphenolic-rich fraction of commercial dry ginger powder. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2015, 50, 2229–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, K.D.P.P.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Inhibition of human low-density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro by ginger extracts. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, A.J.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Oboh, G. Aqueous extracts of two varieties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) inhibit angiotensin I-converting enzyme, iron(II), and sodium nitroprusside-induced lipid peroxidation in the rat heart in vitro. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, A.; Juybari, K.B.; Fatemi, M.J.; Kamarul, T.; Bagheri, A.; Tekiyehmaroof, N.; Sharifi, A.M. Protective effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extract against oxidative stress and mitochondrial apoptosis induced by interleukin-1 beta in cultured chondrocytes. Cells Tissues Organs 2017, 204, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Forero, M.; Sequeda-Castaneda, L.G.; Grismaldo, A.; Iglesias, J.; Celis-Zambrano, C.A.; Schuler, I.; Morales, L. Effect of ginger extract on membrane potential changes and AKT activation on a peroxide-induced oxidative stress cell model. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2018, 30, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Duan, D.; Zhang, X.; Fang, J. Activation of Nrf2 target enzymes conferring protection against oxidative stress in PC12 cells by ginger principal constituent 6-shogaol. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fu, J.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Soroka, D.N.; Prigge, J.R.; Schmidt, E.E.; Yan, F.; Major, M.B.; Chen, X.; et al. Ginger compound [6]-shogaol and its cysteine-conjugated metabolite (M2) activate Nrf2 in colon epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiah, W.; Halzoune, H.; Djaziri, R.; Tabani, K.; Koceir, E.A.; Omari, N. Antioxidant and gastroprotective actions of butanol fraction of Zingiber officinale against diclofenac sodium-induced gastric damage in rats. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Nikzad, H.; Taghizadeh, M.; Taherian, A.; Azami-Tameh, A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Moravveji, A. Protective effect of Zingiber officinale extract on rat testis after cyclophosphamide treatment. Andrologia 2014, 46, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Nitteranon, V.; Chan, L.Y.; Parkin, K.L. Glutathione conjugation attenuates biological activities of 6-dehydroshogaol from ginger. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luettig, J.; Rosenthal, R.; Lee, I.M.; Krug, S.M.; Schulzke, J.D. The ginger component 6-shogaol prevents TNF-alpha-induced barrier loss via inhibition of PI3K/Akt and NF-kappa B signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2576–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, C.; Lo, H.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Wu, S.; Ho, T. Ginger extract and zingerone ameliorated trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in mice via modulation of nuclear factor-kappa B activity and interleukin-1 beta signalling pathway. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, N.; Hasebe, T.; Kaneko, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujiya, M.; Kohgo, Y.; Kono, T.; Wang, C.; Yuan, C.; Bissonnette, M.; et al. TU-100 (Daikenchuto) and ginger ameliorate anti-CD3 antibody induced T cell-mediated murine enteritis: microbe-independent effects involving Akt and Nf-kappa b suppression. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Liu, D.; Han, M.K.; Wang, L.; Merlin, D. Oral delivery of nanoparticles loaded with ginger active compound, 6-shogaol, attenuates ulcerative colitis and promotes wound healing in a murine model of ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis. 2018, 12, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; Lei, C.; Kumar, A.; Hutchins, E.; Mu, J.; Deng, Z.; Luo, C.; et al. Plant-derived exosomal micrornas shape the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehsaz, F.; Farhangi, N.; Mirheidari, L. The effect of Zingiber officinale R. rhizomes (ginger) on plasma pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in well-trained male endurance runners. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 39, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.A.; Ali, S.; Shahnawaz, A.M.; Shafique, I.; Zafar, A.; Khan, M.A.R.; Ghous, T.; Saleem, A.; Andleeb, S. Biological activities of Allium sativum and Zingiber officinale extracts on clinically important bacterial pathogens, their phytochemical and FT-IR spectroscopic analysis. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 30, 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, S. Inhibitory effects of three monoterpenes from ginger essential oil on growth and aflatoxin production of Aspergillus flavus and their gene regulation in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2018, 61, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassan, M.A.; Mohamed, E.H. Immunopathological and antimicrobial effect of black pepper, ginger and thyme extracts on experimental model of acute hematogenous pyelonephritis in albino rats. Int. J. Immunopath. Ph. 2014, 27, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakotiya, A.S.; Tanwar, A.; Narula, A.; Sharma, R.K. Zingiber officinale: Its antibacterial activity on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and mode of action evaluated by flow cytometry. Microb. Pathogenesis. 2017, 107, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, H. Ginger extract inhibits biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Danishuddin, M.; Khan, A.U. Inhibitory effect of Zingiber officinale towards Streptococcus mutans virulence and caries development: in vitro and in vivo studies. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampogu, S.; Baek, A.; Gajula, R.G.; Zeb, A.; Bavi, R.S.; Kumar, R.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, Y.J.; Lee, K.W. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) phytochemicals-gingerenone-A and shogaol inhibit SaHPPK: molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations and in vitro approaches. Ann. Clin. Microb. Anti. 2018, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerilo, S.B.; Rocha, G.H.O.; Tomoike, C.; Mossini, S.A.G.; Grespan, R.; Mikcha, J.M.G.; Machinski, M., Jr. Antifungal properties and inhibitory effects upon aflatoxin production by Zingiber officinale essential oil in Aspergillus flavus. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2016, 51, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Yamamoto-Ribeiro, M.M.; Grespan, R.; Kohiyama, C.Y.; Ferreira, F.D.; Galerani Mossini, S.A.; Silva, E.L.; de Abreu Filho, B.A.; Graton Mikcha, J.M.; Machinski Junior, M. Effect of Zingiber officinale essential oil on Fusarium verticillioides and fumonisin production. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3147–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.S.; Wang, K.C.; Yeh, C.F.; Shieh, D.E.; Chiang, L.C. Fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale) has anti-viral activity against human respiratory syncytial virus in human respiratory tract cell lines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.; Morsy, B.M.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Abo-Seif, M.A.; Zanaty, M.I. Beneficial therapeutic effects of Nigella sativa and/or Zingiber officinale in HCV patients in Egypt. Excli J. 2013, 12, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Deng, G.; Ling, W.; Wu, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, F. Antiproliferative activity of peels, pulps and seeds of 61 fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Deng, G.; Ling, W.; Xu, X. Antiproliferative activities of tea and herbal infusions. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Blando, J.; Silver, E.; Beltran, L.; Sessler, J.; DiGiovanni, J. 6-Shogaol from dried ginger inhibits growth of prostate cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo through inhibition of STAT3 and NF-kappa B signaling. Cancer Prev. Res. 2014, 7, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashmawy, N.E.; Khedr, N.F.; El-Bahrawy, H.A.; Mansour, H.E.A. Ginger extract adjuvant to doxorubicin in mammary carcinoma: study of some molecular mechanisms. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kao, C.; Tseng, Y.; Lo, Y.; Chen, C. Ginger phytochemicals inhibit cell growth and modulate drug resistance factors in docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell. Molecules 2017, 22, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.A.; Sani, N.F.A.; Murad, N.A.; Makpol, S.; Ngah, W.Z.W.; Yusof, Y.A.M. Combined ginger extract & Gelam honey modulate Ras/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathway genes in colon cancer HT29 cells. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Deol, P.K.; Kaur, I.P. Improving the therapeutic efficiency of ginger extract for treatment of colon cancer using a suitably designed multiparticulate system. J. Drug Target 2013, 21, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Turgeon, D.K.; Wright, B.D.; Sidahmed, E.; Ruffin, M.T.; Brenner, D.E.; Sen, A.; Zick, S.M. Effect of ginger root on cyclooxygenase-1 and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase expression in colonic mucosa of humans at normal and increased risk for colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 22, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmbhatt, M.; Gundala, S.R.; Asif, G.; Shamsi, S.A.; Aneja, R. Ginger phytochemicals exhibit synergy to inhibit prostate cancer cell proliferation. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundala, S.R.; Mukkavilli, R.; Yang, C.; Yadav, P.; Tandon, V.; Vangala, S.; Prakash, S.; Aneja, R. Enterohepatic recirculation of bioactive ginger phytochemicals is associated with enhanced tumor growth-inhibitory activity of ginger extract. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Prasad, C.; Wei, Z. Assessment of anti-cancerous potential of 6-gingerol (Tongling white ginger) and its synergy with drugs on human cervical adenocarcinoma cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, M.M.; McConnery, J.R.; Hoskin, D.W. [10]-Gingerol, a major phenolic constituent of ginger root, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2017, 102, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ou, C.; Huang, C.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, T.; Ho, L.; Wang, C.; Shih, C.; Zhou, H.; et al. Carbon dots prepared from ginger exhibiting efficient inhibition of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 4564–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, M.; Iizuka, M.; Kanematsu, R.; Yoshida, M.; Takenaga, K. Anticancer effect of ginger extract against pancreatic cancer cells mainly through reactive oxygen species-mediated autotic cell death. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Moon, M.; Oh, H.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, M.S. Ginger improves cognitive function via NGF-induced ERK/CREB activation in the hippocampus of the mouse. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Kim, H.G.; Ju, M.S.; Ha, S.K.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, M.S. 6-Shogaol, an active compound of ginger, protects dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease models via anti-neuroinflammation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, E.; Lim, S.; Kim, H.G.; Ha, S.K.; Park, H.; Huh, Y.; Oh, M.S. Ginger fermented with Schizosaccharomyces pombe alleviates memory impairment via protecting hippocampal neuronal cells in amyloid beta(1-42) plaque injected mice. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Ge, C.; Duan, D.; Zhang, B.; Cui, X.; Peng, S.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J. Activation of the phase II enzymes for neuroprotection by ginger active constituent 6-dehydrogingerdione in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5507–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, L.; Xiao, D.; Zong, S.; He, J. Protective effects of ginger root extract on Alzheimer disease-induced behavioral dysfunction in rats. Rejuv. Res. 2013, 16, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.G.; Oh, H.; Lee, P.K.J.; Ha, S.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, Y.; Huh, Y.; Oh, M.S. 6-Shogaol, an active constituent of ginger, attenuates neuroinflammation and cognitive deficits in animal models of dementia. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2014, 449, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, L.; Bennett, D.; Guo, Y.; Key, T.J.; Bian, Z.; Sherliker, P.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, M.; Azarbayjani, M.A.; Abolmaesoomi, M.; Yusof, A.; Abidin, N.Z.; Rahimi, E.; Feizolahi, F.; Akbari, M.; Seyedjalali, S.; Dehghan, F. Ginger extract and aerobic training reduces lipid profile in high-fat fed diet rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmaco. 2016, 20, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi, A.J.; Thome, G.R.; Morsch, V.M.; Bottari, N.B.; Baldissarelli, J.; de Oliveira, L.S.; Goularte, J.F.; Bello-Klein, A.; Oboh, G.; Chitolina Schetinger, M.R. Dietary supplementation of ginger and turmeric rhizomes modulates platelets ectonucleotidase and adenosine deaminase activities in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Las Heras, N.; Valero-Munoz, M.; Martin-Fernandez, B.; Ballesteros, S.; Lopez-Farre, A.; Ruiz-Roso, B.; Lahera, V. Molecular factors involved in the hypolipidemic-and insulin-sensitizing effects of a ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) extract in rats fed a high-fat diet. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Me. 2017, 42, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lee, M.; Jung, S.; Kim, S.; Park, H.; Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Jo, Y.; Kim, I.; et al. Ginger extract increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and serum HDL-cholesterol level in high-fat diet-fed rats. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 29, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Heiss, E.H.; Sider, N.; Schinkovitz, A.; Groblacher, B.; Guo, D.; Bucar, F.; Bauer, R.; Dirsch, V.M.; Atanasov, A.G. Identification and characterization of [6]-shogaol from ginger as inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Horng, C.; Tsai, S.; Lee, Y.; Hsu, S.; Tsai, Y.; Tsai, F.; Chiang, J.; Kuo, D.; Yang, J. Relaxant and vasoprotective effects of ginger extracts on porcine coronary arteries. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 2420–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Li, R.; Chu, D.; Ma, Y. Evaluation of daily ginger consumption for the prevention of chronic diseases in adults: A cross-sectional study. Nutrition 2017, 36, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, K.; Hashizume, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Minegishi, Y.; Hase, T.; Shimotoyodome, A. Ginger extract prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice via activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, R.H.; Elnour, W.A. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of ginger and orlistat on obesity management, pancreatic lipase and liver peroxisomal catalase enzyme in male albino rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmaco. 2013, 17, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Attari, V.E.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Mehralizadeh, S.; Mahluji, S. Changes of serum adipocytokines and body weight following Zingiber officinale supplementation in obese women: A RCT. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 2129–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Matsuzaki, K.; Katakura, M.; Hara, T.; Tanabe, Y.; Shido, O. Oral intake of encapsulated dried ginger root powder hardly affects human thermoregulatory function, but appears to facilitate fat utilization. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.; Ahmedna, M.; Sang, S. Bioactive ginger constituents alleviate protein glycation by trapping methylglyoxal. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015, 28, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, C.; Rashid, M.R.; Sang, S.; Ahmedna, M. Specific bioactive compounds in ginger and apple alleviate hyperglycemia in mice with high fat diet-induced obesity via Nrf2 mediated pathway. Food Chem. 2017, 226, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Samad, M.; Bin Mohsin, M.N.A.; Razu, B.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Mahzabeen, S.; Unnoor, N.; Muna, I.A.; Akhter, F.; Ul Kabir, A.; Hannan, J.M.A. [6]-Gingerol, from Zingiber officinale, potentiates GLP-1 mediated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway in pancreatic beta-cells and increases RAB8/RAB10-regulated membrane presentation of GLUT4 transporters in skeletal muscle to improve hyperglycemia in Lepr(db/db) type 2 diabetic mice. BMC Complem. Altern. M. 2017, 17, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Arablou, T.; Aryaeian, N.; Valizadeh, M.; Sharifi, F.; Hosseini, A.; Djalali, M. The effect of ginger consumption on glycemic status, lipid profile and some inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tran, V.H.; Kota, B.P.; Nammi, S.; Duke, C.C.; Roufogalis, B.D. Preventative effect of Zingiber officinale on insulin resistance in a high-fat high-carbohydrate diet-fed rat model and its mechanism of action. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 115, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongare, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Mathur, R.; Saxena, R.; Mathur, S.; Agarwal, R.; Nag, T.C.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, P. Zingiber officinale attenuates retinal microvascular changes in diabetic rats via anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic mechanisms. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- Mahluji, S.; Attari, V.E.; Mobasseri, M.; Payahoo, L.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Golzari, S.E.J. Effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on plasma glucose level, HbA1c and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; McCarthy, A.L.; Ried, K.; McKavanagh, D.; Vitetta, L.; Sali, A.; Lohning, A.; Isenring, E. The effect of a standardized ginger extract on chemotherapy-induced nausea-related quality of life in patients undergoing moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy: A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, P.; Cortinovis, D.; Fatigoni, S.; Rocca, M.C.; Fabi, A.; Seminara, P.; Ripamonti, C.; Alfieri, S.; Granata, R.; Bergamini, C.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of a ginger extract in the management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2547–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Hosseini, F.S. Investigating the effects of inhaling ginger essence on post-nephrectomy nausea and vomiting. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalava, A.; Darji, S.J.; Kalstein, A.; Yarmush, J.M.; SchianodiCola, J.; Weinberg, J. Efficacy of ginger on intraoperative and postoperative nausea and vomiting in elective cesarean section patients. Eur. J. Obstet. Gyn. R. B. 2013, 169, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.M.; Teleni, L.; McCarthy, A.L.; Vitetta, L.; McKavanagh, D.; Thomson, D.; Isenring, E. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic literature review. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Park, C.; Park, Y.S.; Jin, Y. Ginger and its pungent constituents non-competitively inhibit serotonin currents on visceral afferent neurons. Korean J. Physiol. Pha. 2014, 18, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabaghzadeh, F.; Khalili, H.; Dashti-Khavidaki, S.; Abbasian, L.; Moeinifard, A. Ginger for prevention of antiretroviral-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized clinical trial. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani, Z.; Shojaei, E.; Khalili, H. Ginger for prevention of antituberculosis-induced gastrointestinal adverse reactions including hepatotoxicity: A randomized pilot clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatty, P.L.; Haniadka, R.; Valder, B.; Arora, R.; Baliga, M.S. Ginger in the prevention of nausea and vomiting: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2013, 53, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.A.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Wakita, R.; Emala, C.W. Active components of ginger potentiate beta-agonist-induced relaxation of airway smooth muscle by modulating cytoskeletal regulatory proteins. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. 2014, 50, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mangprayool, T.; Kupittayanant, S.; Chudapongse, N. Participation of citral in the bronchodilatory effect of ginger oil and possible mechanism of action. Fitoterapia 2013, 89, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Shahzad, M.; Asim, M.B.R.; Imran, M.; Shabbir, A. Zingiber officinale ameliorates allergic asthma via suppression of Th2-mediated immune response. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, K.; Nosalova, G.; Sivova, V.; Ray, B. Structural elements and cough suppressing activity of polysaccharides from Zingiber officinale rhizome. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatpanahi, Z.V.; Mokhtari, M.; Taleban, F.A.; Alavi, F.; Surmaghi, M.H.S.; Mehrabi, Y.; Shahbazi, S. Effect of enteral feeding with ginger extract in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Crit. Care. 2013, 28, 217.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Nakahashi, E.; Obayashi, M.; Sugihara, K.; Qiao, S.; Iida, M.; Kumasaka, M.Y.; Yajima, I.; Goto, Y.; et al. Prevention of allergic rhinitis by ginger and the molecular basis of immunosuppression by 6-gingerol through T cell inactivation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 27, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Lee, W.; Lin, Y.; Ho, C.; Lu, K.; Lin, S.; Panyod, S.; Chu, Y.; Sheen, L. Ginger essential oil ameliorates hepatic injury and lipid accumulation in high fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.A.P.; Prata, M.M.G.; Oliveira, I.C.M.; Alves, N.T.Q.; Freitas, R.E.M.; Monteiro, H.S.A.; Silva, J.A.; Vieira, P.C.; Viana, D.A.; Liborio, A.B.; et al. Gingerol fraction from Zingiber officinale protects against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Ch. 2014, 58, 1872–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, H.; Keshavarzi, B.; Shirpoor, A.; Gharalari, F.H.; Rasmi, Y. Rescue effects of ginger extract on dose dependent radiation-induced histological and biochemical changes in the kidneys of male Wistar rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Raghu, R.; Lin, S.; Wang, S.; Kuo, C.; Tseng, Y.J.; Sheen, L. Metabolomics of ginger essential oil against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11231–11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashefi, F.; Khajehei, M.; Alavinia, M.; Golmakani, E.; Asili, J. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on heavy menstrual bleeding: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghbooli, M.; Golipour, F.; Esfandabadi, A.M.; Yousefi, M. Comparison between the efficacy of ginger and sumatriptan in the ablative treatment of the common migraine. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschke, R.; Xuan, T.D. Viewpoint: A contributory role of shell ginger (Alpinia zerumbet) for human longevity in Okinawa, Japan? Nutrients 2018, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Yu, X.; Xiao, M.; Sha, L.; Ren-You, G.; Ya, L.; Hua-Bin, L. Bioactivity, health benefits, and related molecular mechanisms of curcumin: Current progress, challenges, and perspectives. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1553. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L.; Huang, M.J.; Tan, D.Q.; Liao, Q.H.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, Y.S. Effects of soil moisture content on the growth and physiological status of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constituent | Study Type | Subjects | Dose | Potential Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-shogaol | In vivo | HCT-116 human colon cancer cells | 20 μM | Increasing the intracellular GSH/GSSG ratio; decreasing the level of ROS; upregulating the expression of AKR1B10, FTL, GGTLA4, HO-1, MT1, GCLC, and GCLM genes | [33] |

| In vitro | Wild-type and Nrf2−/− C57BL/6J mice | 100 mg/kg | Upregulating the expression of MT1, HO-1, and GCLC | ||

| Ginger oleoresin | In vitro | Human mesenchymal stem cells | 100 μg/mL | Reducing ROS production; inducing the translocation of Nrf2 to the cell nucleus; activating HO-1 and NQO1 gene expression | [14] |

| Ginger phenylpropanoids | In vitro | BJ foreskin fibroblasts | 40 μg/mL | Increasing Nrf2 activity and the level of GSTP1 | [15] |

| 6-gingerol-rich fraction | In vivo | Female Wistar rats | 50 and 100 mg/kg | Reducing the levels of H2O2 and MDA; increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes and the level of GSH | [25] |

| Ginger extract | In vivo | Male Wistar albino rats | 100 mg/kg | Reducing the level of MDA; preventing the depletion of catalase activity and GSH content | [34] |

| In vitro | C28I2 human chondrocyte cells | 5 and 25 μg/mL | Increasing the gene expression of antioxidant enzymes; reducing the content of ROS and lipid peroxidation | [30] | |

| In vitro | HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells | 200 and 400 μg/mL | Reducing the generation of ROS | [31] | |

| In vitro | Rat heart homogenates | 78–313 μg/mL | Decreasing the level of MDA | [29] |

| Constituent | Study Type | Subjects | Dose | Potential Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-shogaol | In vitro | HT-29/B6 and Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells | 100 μM | Inhibiting the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways | [37] |

| 6-shogaol and 6-gingerol, 6-dehydroshogaol | In vitro | RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cells | 2.5, 5, and 10 μM | Inhibiting the production of NO and PGE2 | [36] |

| 6-gingerol-rich fraction | In vivo | Female Wistar rats | 50 and 100 mg/kg | Increasing the levels of myeloperoxidase, NO, and TNF-α | [25] |

| GDNPs 2 | In vivo | Female C57BL/6 FVB/NJ mice | 0.3 mg | Increasing the levels of IL-10 and IL-22; decreasing the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β | [4] |

| Ginger extract and zingerone | In vivo | Female BALB/c mice | 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 mg/kg | Inhibiting NF-κB activation and decreasing the level of IL-1β | [38] |

| Ginger extract | In vivo | C57BL6/J mice | 50 mg/mL | Inhibiting the production of TNF-α; Activating Akt and NF-κB | [39] |

| Constituent | Study Type | Subjects | Dose | Potential Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginger essential oil | In vitro | Fusarium verticillioides | 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, and 5000 μg/mL | Reducing ergosterol biosynthesis; affecting membrane integrity; decreasing the production of fumonisin B1 and fumonisin B2 | [51] |

| In vitro | Aspergillus flavus | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL | Reducing ergosterol biosynthesis; affecting membrane integrity; inhibiting the production of aflatoxin | [50] | |

| Gingerenone-A and shogaol | In vitro | Staphylococcus aureus | 25, 50, and 75 μg/mL | Inhibiting the activity of 6-hydroxymethyl-7, 8-dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase | [49] |

| Ginger extract | In vitro | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL | Affecting membrane integrity; inhibiting biofilm formation | [46] |

| In vitro | Streptococcus mutans | 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 μg/mL | Inhibiting biofilm formation, glucan synthesis, and adherence | [48] | |

| In vitro | HEp-2 human larynx epidermoid carcinoma cells and A549 human lung carcinoma cells with HRSV | 10, 30, 100, and 300 μg/mL | Blocking viral attachment and internalization | [52] |

| Constituent | Study Type | Subjects | Dose | Potential Mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-shogaol | In vitro | LNCaP, DU145, and PC-3 human prostate cancer cells | 10, 20, and 40 μM | Inducing apoptosis; inhibiting STAT3 and NF-κB signaling; downregulating the expression of cyclin D1, survivin, c-Myc, and Bcl2 | [57] |

| 6-gingerol | In vitro | HeLa human cervical adenocarcinoma cells | 60, 100, and 140 μM | Inducing cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1-phase; decreasing the levels of cyclin A, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1; increasing the expression of caspase; inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway | [65] |

| 10-gingerol | In vitro | Human and mouse breast carcinoma cells | 50, 100, and 200 μM | Inhibiting cell growth; reducing cell division; inducing S phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis | [66] |

| 6-gingerol, 10-gingerol, 6-shogaol, and 10-shogaol | In vitro | PC-3 human prostate cancer cells | 1,10, and 100 μM | Inhibiting prostate cancer cell proliferation; downregulating the expression of MRP1and GSTπ | [59] |

| GDNPs 2 | In vivo | Female C57BL/6 mice | 0.3 mg | Suppressing the expression of cyclin D1; inhibiting intestinal epithelial cell proliferation | [4] |

| Ginger extract | In vitro | HT29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells | 2–10 mg/mL | Promoting apoptosis; upregulating the caspase 9 gene; downregulating KRAS, ERK, Akt, and Bcl-xL | [60] |

| In vivo | Female Swiss albino mice | 100 mg/kg | Activating AMPK; decreasing the expression of cyclin D1 and the level of NF-κB; increasing the expression of p53 | [58] | |

| Ginger extract with alginate beads | In vivo | Male Wistar rats | 50 mg/kg | Increasing the activity of NADH dehydrogenase and succinate dehydrogenase | [61] |

| Ginger extract-based fluorescent carbon nanodots | In vitro | HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells | 1.11 mg/mL | Increasing the level of ROS; upregulating the expression of p53; promoting apoptosis | [67] |

| Items | Ginger | Shell Ginger | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific name | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Alpinia zerumbet (Pers.) B.L. Burtt & R.M. Sm. | [115,117] |

| Family and genus | Zingiberaceae family and Zingiber genus | Zingiberaceae family and Alpinia genus | [115,117] |

| Edible parts | Rhizomes | Leaves and rhizomes | [8,115] |

| Bioactive compounds | Gingerols, shogaols, paradols, and essential oils | Dihydro-5,6-dehydrokawain, 5,6-dehydrokawain, essential oils, and flavonoids | [2,44,115] |

| Biological activities | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, cardiovascular protective, antiobesity, antidiabetic, neuroprotective, respiratory protective, antinausea, and antiemetic activities | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, cardiovascular protective, antiobesity, antidiabetic activities, longevity | [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,115] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8060185

Mao Q-Q, Xu X-Y, Cao S-Y, Gan R-Y, Corke H, Beta T, Li H-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods. 2019; 8(6):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8060185

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Qian-Qian, Xiao-Yu Xu, Shi-Yu Cao, Ren-You Gan, Harold Corke, Trust Beta, and Hua-Bin Li. 2019. "Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe)" Foods 8, no. 6: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8060185

APA StyleMao, Q.-Q., Xu, X.-Y., Cao, S.-Y., Gan, R.-Y., Corke, H., Beta, T., & Li, H.-B. (2019). Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods, 8(6), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8060185