Old Fashioned vs. Ultra-Processed-Based Current Diets: Possible Implication in the Increased Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease in Childhood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microbiota, Gut Health and Autoimmunity

2.1. Type 1 Diabetes

2.2. Celiac Disease

3. Newer Is Not Always Better

4. Dietary Components Shape Gut Microbiota

4.1. Complex Carbohydrates vs. Sugars

4.2. Unsaturated vs. Saturated Fats

4.3. Plant vs. Animal Protein

4.4. Food Additives

5. Are Old Fashioned Diets Better?

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017, 40 (Suppl. 1), S11–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettitt, D.J.; Talton, J.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Imperatore, G.; Lawrence, J.M.; Liese, A.D.; Linder, B.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Pihoker, C.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Rubio-Tapia, A.; van Dyke, C.T.; Melton, L.J.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Lahr, B.D.; Murray, J.A. Increasing incidence of celiac disease in a North American population. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namatovu, F.; Sandström, O.; Olsson, C.; Lindkvist, M.; Ivarsson, A. Celiac disease risk varies between birth cohorts, generating hypotheses about causality: Evidence from 36 years of population-based follow-up. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazeli Farsani, S.; Souverein, P.C.; van der Vorst, M.M.; Knibbe, C.A.; Herings, R.M.; de Boer, A.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K. Increasing trends in the incidence and prevalence rates of type 1 diabetes among children and adolescents in the Netherlands. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Wong, F.S.; Wen, L. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, environment in early life and type 1 diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 119, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdu, E.F.; Galipeau, H.J.; Jabri, B. Novel players in coeliac disease pathogenesis: Role of the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knip, M.; Siljander, H. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endesfelder, D.; Engel, M.; Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Ardissone, A.N.; Achenbach, P.; Hummel, S.; Winkler, C.; Atkinson, M.; Schatz, D.; Triplett, E.; et al. Towards a functional hypothesis relating anti-islet cell autoimmunity to the dietary impact on microbial communities and butyrate production. Microbiome 2016, 4, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Triplett, E.W. A model for the role of gut bacteria in the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Castro, I.R.; Cannon, G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Canella, D.S.; Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Cannon, G. Household availability of ultra-processed foods and obesity in nineteen European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-León, M.E.; Calderón de la Barca, A.M. Diet, Microbiota and Immune System in Type 1 Diabetes Development and Evolution. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9171–9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-León, M.E.; Petrosino, J.F.; Ajami, N.J.; Domínguez-Bello, M.G.; Calderón de la Barca, A.M. Fecal microbiota imbalance in Mexican children with type 1 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Covián, D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Margolles, A.; Gueimonde, M.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Salazar, N. Intestinal Short Chain Fatty Acids and their Link with Diet and Human Health. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaarala, O. Is the origin of type 1 diabetes in the gut? Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkanani, A.K.; Hara, N.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Ir, D.; Robertson, C.E.; Wagner, B.D.; Frank, D.N.; Zipris, D. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota Correlate With Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3510–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Goffau, M.C.; Luopajärvi, K.; Knip, M.; Ilonen, J.; Ruohtula, T.; Härkönen, T.; Orivuori, L.; Hakala, S.; Welling, G.W.; Harmsen, H.J.; et al. Fecal microbiota composition differs between children with β-cell autoimmunity and those without. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Ardissone, A.N.; Dias, R.; Simell, V.; Leonard, M.T.; Kemppainen, K.M.; Drew, J.C.; Schatz, D.; Atkinson, M.A.; Kolaczkowski, B.; et al. Bacteroides. dorei dominates gut microbiome prior to autoimmunity in Finnish children at high risk for type 1 diabetes. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehik, K.; Lynch, K.F.; Schatz, D.A.; Akolkar, B.; Hagopian, W.; Rewers, M.; She, J.X.; Simell, O.; Toppari, J.; Ziegler, A.G.; et al. Reversion of β-Cell Autoimmunity Changes Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viggiano, D.; Ianiro, G.; Vanella, G.; Bibbò, S.; Bruno, G.; Simeone, G.; Mele, G. Gut barrier in health and disease: Focus on childhood. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collado, M.C.; Donat, E.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Calabuig, M.; Sanz, Y. Specific duodenal and faecal bacterial groups associated with paediatric coeliac disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 62, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cagno, R.; De Angelis, M.; De Pasquale, I.; Ndagijimana, M.; Vernocchi, P.; Ricciuti, P.; Gagliardi, F.; Laghi, L.; Crecchio, C.; Guerzoni, M.E.; et al. Duodenal and faecal microbiota of celiac children: Molecular, phenotype and metabolome characterization. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, E.; Laparra, J.M.; Sanz, Y. Discerning the role of Bacteroides fragilis in celiac disease pathogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6507–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Argenio, V.; Casaburi, G.; Precone, V.; Pagliuca, C.; Colicchio, R.; Sarnataro, D.; Discepolo, V.; Kim, S.M.; Russo, I.; Del Vecchio Blanco, G.; et al. Metagenomics Reveals Dysbiosis and a Potentially Pathogenic N. flavescens Strain in Duodenum of Adult Celiac Patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez, V.; Ayala, J.; Vespa, C.; Araya, M. The gluten-free basic food basket: A problem of availability, cost and nutritional composition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzeo, T.; Cauzzi, S.; Brighenti, F.; Pellegrini, N. The development of a composition database of gluten-free products. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missbach, B.; Schwingshackl, L.; Billmann, A.; Mystek, A.; Hickelsberger, M.; Bauer, G.; König, J. Gluten-free food database: The nutritional quality and cost of packaged gluten-free foods. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moubarac, J.C.; Batal, M.; Martins, A.P.; Claro, R.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C. Processed and ultra-processed food products: Consumption trends in Canada from 1938 to 2011. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2014, 75, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djupegot, I.L.; Nenseth, C.B.; Bere, E.; Bjørnarå, H.B.T.; Helland, S.H.; Øverby, N.C.; Torstveit, M.K.; Stea, T.H. The association between time scarcity, sociodemographic correlates and consumption of ultra-processed foods among parents in Norway: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization; World Health Organization regional office for the Americas. Ultra-Processed Food and Drink Products in Latin America: Trends, Impact on Obesity, Policy Implications; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fardet, A. Minimally processed foods are more satiating and less hyperglycemic than ultra-processed foods: A preliminary study with 98 ready-to-eat foods. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moubarac, J.C.; Batal, M.; Louzada, M.L.; Martinez Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite 2017, 108, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.P.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Moubarac, J.C.; Monteiro, C.A. Increased contribution of ultra-processed food products in the Brazilian diet (1987–2009). Rev. Saude Publica 2013, 47, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, R.D.; Lopes, A.C.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017, 30, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, A.; Saldamando, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Ares, G. Package design and nutritional profile of foods targeted at children in supermarkets in Montevideo, Uruguay. Cad. Saude Publica 2017, 33, e00032116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnopp, E.V.; Vaz, J.D.; Schafer, A.A.; Muniz, L.C.; Souza, R.L.; Santos, I.D.; Gigante, D.P.; Assunção, M.C. Food consumption of children younger than 6 years according to the degree of food processing. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2017, 93, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, L.F.; Fonseca, S.C.; Garcia Rosa, M.L.; Yokoo, E.M. Relationship between ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in adolescents from a Brazilian Family Doctor Program. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, F.; Campagnolo, P.D.; Hoffman, D.J.; Vitolo, M.R. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children’s lipid profiles: A longitudinal study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkin, T.J. The convergence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in childhood: The accelerator hypothesis. Pediatr. Diabetes 2012, 13, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatsunenko, T.; Rey, F.E.; Manary, M.J.; Trehan, I.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Baldassano, R.N.; Anokhin, A.P.; et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14691–14696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Van de Wiele, T.; Gewirtz, A. Dietary Emulsifiers Directly Impact the Human Gut Microbiota Increasing Its Pro-inflammatory Potential and Ability to Induce Intestinal Inflammation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, S5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Roy, N.C.; Guo, Y.; Jia, H.; Ryan, L.; Samuelsson, L.; Thomas, A.; Plowman, J.; Clerens, S.; Day, L.; et al. Human Breast Milk and Infant Formulas Differentially Modify the Intestinal Microbiota in Human Infants and Host Physiology in Rats. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashtanova, D.A.; Popenko, A.S.; Tkacheva, O.N.; Tyakht, A.B.; Alexeev, D.G.; Boytsov, S.A. Association between the gut microbiota and diet: Fetal life, early childhood, and further life. Nutrition 2016, 32, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wopereis, H.; Oozeer, R.; Knipping, K.; Belzer, C.; Knol, J. The first thousand days—Intestinal microbiology of early life: Establishing a symbiosis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 25, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiminez, J.A.; Uwiera, T.C.; Abbott, D.W.; Uwiera, R.R.; Inglis, G.D. Impacts of resistant starch and wheat bran consumption on enteric inflammation in relation to colonic bacterial community structures and short-chain fatty acid concentrations in mice. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyaya, B.; McCormack, L.; Fardin-Kia, A.R.; Juenemann, R.; Nichenametla, S.; Clapper, J.; Specker, B.; Dey, M. Impact of dietary resistant starch type 4 on human gut microbiota and immunometabolic functions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald, S.; Schioldan, A.G.; Moore, M.E.; Dige, A.; Lærke, H.N.; Agnholt, J.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Hermansen, K.; Marco, M.L.; Gregersen, S.; et al. Effects of Arabinoxylan and Resistant Starch on Intestinal Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomised Crossover Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Baraldi, L.G.; Louzada, M.L.; Moubarac, J.C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, E.E.; Hsu, T.M.; Jones, R.B.; Fodor, A.A.; Goran, M.I.; Kanoski, S.E. Early-Life Sugar Consumption Affects the Rat Microbiome Independently of Obesity. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, J.; Yamamoto, A.; Palermo-Conde, L.A.; Higashi, K.; Sonomoto, K.; Tan, J.; Lee, Y.K. Impact of Westernized Diet on Gut Microbiota in Children on Leyte Island. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoen, S.; Jergens, S.; Barbaresko, J.; Nöthlings, U.; Kersting, M.; Remer, T.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Ziegler, A.G.; Hummel, S. Diet Quality during Infancy and Early Childhood in Children with and without Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A DEDIPAC Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.S.; Raab, J.; Haupt, F.; Aschemeier, B.; Wosch, A.; Ried, C.; Kordonouri, O.; Ziegler, A.G.; Winkler, C. Evaluating the diet of children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes: First results from the TEENDIAB study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, M.M.; Frederiksen, B.; Seifert, J.A.; Kroehl, M.; Rewers, M.; Norris, J.M. Sugar intake is associated with progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byerley, L.O.; Samuelson, D.; Blanchard, E.; Luo, M.; Lorenzen, B.N.; Banks, S.; Ponder, M.A.; Welsh, D.A.; Taylor, C.M. Changes in the gut microbial communities following addition of walnuts to the diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 48, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, R.C.; Seira Oriach, C.; Murphy, K.; Moloney, G.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids critically regulate behaviour and gut microbiota development in adolescence and adulthood. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 59, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noriega, B.S.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salyakina, D.; Coffman, J. Understanding the Impact of Omega-3 Rich Diet on the Gut Microbiota. Case Rep. Med. 2016, 2016, 3089303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Dai, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, A.Z. ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids ameliorate type 1 diabetes and autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1757–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamo, P.; Palmieri, G.; Cocca, E.; Ferrandino, I.; Gogliettino, M.; Monaco, A.; Maurano, F.; Rossi, M. Adaptive response activated by dietary cis9, trans11 conjugated linoleic acid prevents distinct signs of gliadin-induced enteropathy in mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, J.C.; Campbell, S.; Moreau, M.; Patel, F.; Brooks, A.I.; Zhou, Y.X.; Häggblom, M.M.; Storch, J. Bacterial communities in the small intestine respond differently to those in the caecum and colon in mice fed low- and high-fat diets. Microbiology 2017, 163, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agus, A.; Denizot, J.; Thévenot, J.; Martinez-Medina, M.; Massier, S.; Sauvanet, P.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Denis, S.; Hofman, P.; Bonnet, R.; et al. Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to Adherent-Invasive E. coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, V.; Gouda, M.; Moncivaiz, J.; Gordon, A.; Reo, N.V.; Hussein, L.; Paliy, O. Differences in Gut Metabolites and Microbial Composition and Functions between Egyptian and U.S. Children Are Consistent with Their Diets. mSystems 2017, 2, e00169-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarpia, L.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. Dietary protein content for an optimal diet: A clinical view. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhao, F.; Shi, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, G. Meat, dairy and plant proteins alter bacterial composition of rat gut bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, H.W.; Liu, J.F. Cow milk induced allergies (CMA) and asthma in new born. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knip, M.; Virtanen, S.M.; Seppä, K.; Ilonen, J.; Savilahti, E.; Vaarala, O.; Reunanen, A.; Teramo, K.; Hämäläinen, A.M.; Paronen, J.; et al. Dietary intervention in infancy and later signs of beta-cell autoimmunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaarala, O.; Knip, M.; Paronen, J.; Hämäläinen, A.M.; Muona, P.; Väätäinen, M.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; Akerblom, H.K. Cow’s milk formula feeding induces primary immunization to insulin in infants at genetic risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 1999, 48, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinchese, G.; Cavaliere, G.; Canani, R.B.; Matamoros, S.; Bergamo, P.; De Filippo, C.; Aceto, S.; Gaita, M.; Cerino, P.; Negri, R.; et al. Human, donkey and cow milk differently affects energy efficiency and inflammatory state by modulating mitochondrial function and gut microbiota. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón de la Barca, A.M.; Mejía-León, M.E. Are Gluten-Free Foods Just for Patients with a Gluten-Related Disease? In Celiac Disease and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity, 1st ed.; Rodrigo, L., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaben, A.S.; Turner, J.; Shirton, L.; Samuel, T.M.; Persad, R.; Mager, D. Assessing Nutritional Quality and Adherence to the Gluten-free Diet in Children and Adolescents with Celiac Disease. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anania, C.; Pacifico, L.; Olivero, F.; Perla, F.M.; Chiesa, C. Cardiometabolic risk factors in children with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, G.; Nadal, I.; Collado, M.C.; Sanz, Y. Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminero, A.; Nistal, E.; Arias, L.; Vivas, S.; Comino, I.; Real, A.; Sousa, C.; de Morales, J.M.; Ferrero, M.A.; Rodríguez-Aparicio, L.B.; et al. A gluten metabolism study in healthy individuals shows the presence of faecal glutenasic activity. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Nutrition. Global Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding. Fifty-fifth World Health Assembly. 2002. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA55/ea5515.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 13 October 2017).

- Lerner, A.; Matthias, T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015, 14, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csáki, K.F. Synthetic surfactant food additives can cause intestinal barrier dysfunction. Med. Hypotheses 2011, 76, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; Koren, O.; Goodrich, J.K.; Poole, A.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Ley, R.E.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2015, 519, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swidsinski, A.; Ung, V.; Sydora, B.C.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Doerffel, Y.; Verstraelen, H.; Fedorak, R.N. Bacterial overgrowth and inflammation of small intestine after carboxymethylcellulose ingestion in genetically susceptible mice. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Kolanos, R.; DiNovi, M.J.; Mattia, A.; Kaneko, K.J. Dietary exposures for the safety assessment of seven emulsifiers commonly added to foods in the United States and implications for safety. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2017, 34, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Nava, A.; Noriega, L.G.; Tovar, A.R.; Granados, O.; Perez-Cruz, C.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Torres, N. Food combination based on a pre-hispanic Mexican diet decreases metabolic and cognitive abnormalities and gut microbiota dysbiosis caused by a sucrose-enriched high-fat diet in rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1501023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Díaz, I.; Fernández-Navarro, T.; Sánchez, B.; Margolles, A.; González, S. Mediterranean diet and faecal microbiota: A transversal study. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2347–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick-Bauer, M.; Yeh, M.C. The health advantage of a vegan diet: Exploring the gut microbiota connection. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4822–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

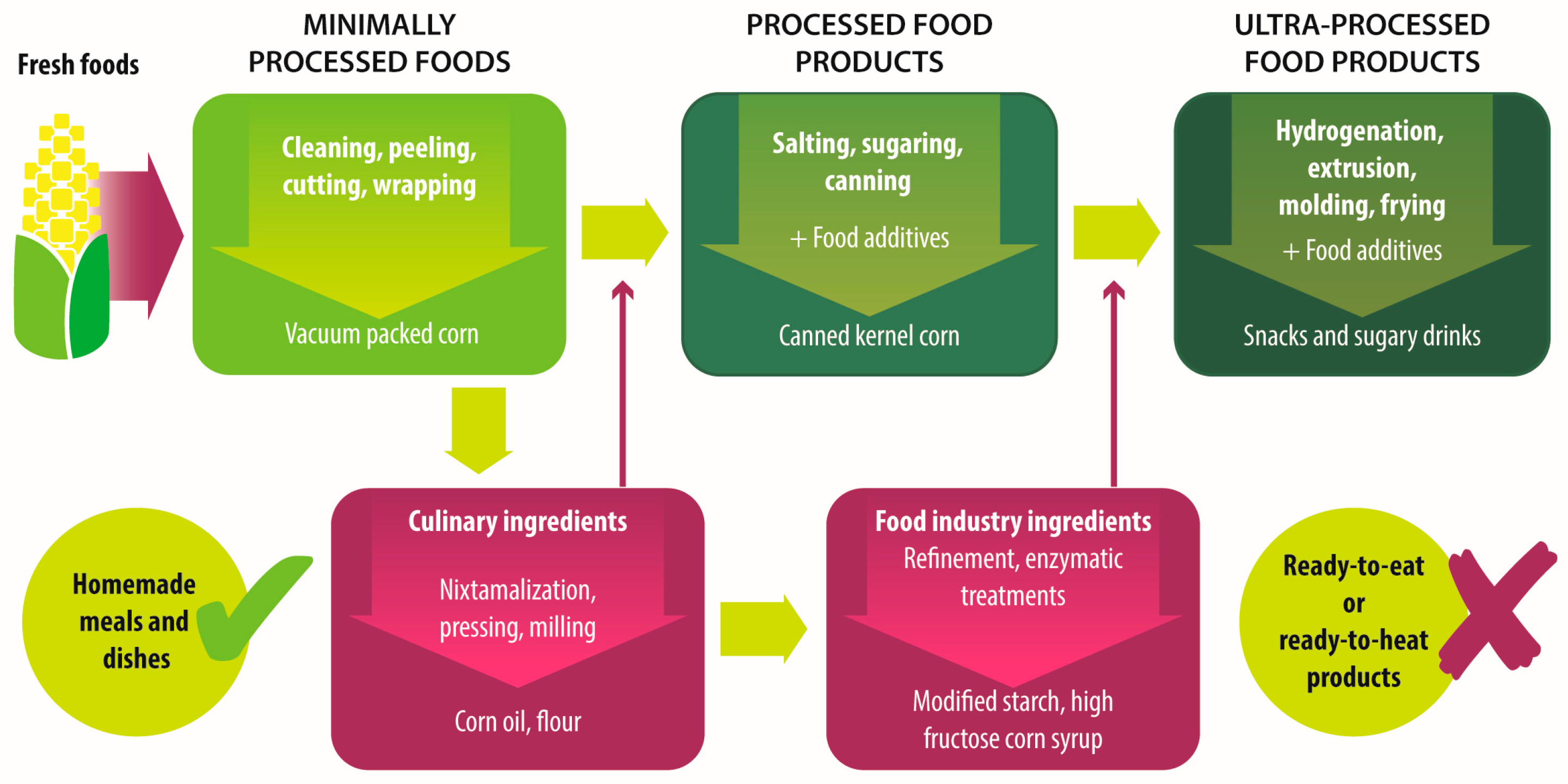

| Group | Definition | Processing | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unprocessed foods | Fresh foods directly obtained from plants or animals. | No industrial processing. | Fresh fruits, vegetables, meat, eggs, grains and legumes. |

| Minimally processed foods | Physical alteration of unprocessed foods. | Peeling, cutting, drying, pasteurization, refrigeration, freezing, vacuum packing, simple wrapping. | Chilled, frozen or dried fruits, vegetables, meat and poultry; pasteurized or powdered milk; vegetables or fruit juices without added sugar. |

| Processed culinary ingredients | Substances extracted from unprocessed or minimally processed foods used to prepare dishes and meals. | Pressing, refining, grinding, milling. | Salt, sugar, flour, vegetable oil, starches, butter, etc. |

| Processed food industry ingredients | Substances extracted from unprocessed or minimally processed foods used in the formulation of ultra-processed foods. | Hydrogenation, hydrolysis, use of enzymes and additives. | High fructose corn syrup, lactose, milk and soy proteins. |

| Processed foods | Products made by adding sugar, salt, oil, fats or other culinary ingredients, to minimally processed foods. | Preservation or cooking methods, non-alcoholic fermentation. | Bread, cheese, canned vegetables and legumes, fruits in syrup, salted nuts and seeds, smoked and salted meat. |

| Ultra-processed foods | Industrial formulations manufactured mainly from processed food industry ingredients. | Frying, deep frying, curing, extrusion, molding, extensive use of additives, such as preservatives, colorants, flavorings, non-sugar sweeteners, emulsifiers, etc. | Ready-to-heat, ready-to-eat or ready-to-drink products like carbonated drinks, sweet or savory snacks, breakfast cereals, fruit yoghurt, sausages, hams, instant soups, pre-prepared meals and dishes, infant formulas, baby food. |

| Characteristic | Old Fashioned Diet (Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Food-Based Diet) | Ultra-Processed Products-Based Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber * | ↑ Dietary fiber from vegetables, whole grains and cereals. | ↓ Dietary fiber due to the refining process. |

| Fat * | Balance between saturated and unsaturated fats, depending on food selection. | ↑ Total fat and trans fat added or generated by the processes of baking and frying. |

| Carbohydrates * | ↑ Complexes carbohydrates and natural resistant starch from whole grains and cereals. | ↑ Added sugars in sweets, confectionary and soft drinks. |

| Protein * | ↑ Amount and quality of protein from fresh meat, eggs, fish and poultry. | ↓ Quantity of protein often accompanied by added fat. |

| Micronutrients * | ↑ Quantity of vitamins and minerals if all food groups are included in a balanced way. | ↓ Concentration of vitamins and minerals due to the refining process if not fortified. |

| Sodium * | Sodium intake depends mainly on the added salt to foods. | ↑ Amounts of sodium. |

| Additives * | Free of additives. | Extensive use of additives like emulsifiers, coloring, flavoring, and preservatives. |

| Effect on ç: | ||

| Gut microbiota ‡ | Eubiosis with high abundance of butyrate producer bacteria. | Dysbiosis marked by Bacteroides and gram-negative Proteobacteria. |

| Bacterial Metabolites γ | ↑ Production of butyrate | ↑ Production of acetate and other short chain fatty acids. |

| Immune response § | Anti-inflammatory response. | Pro-inflammatory response. |

| Epithelia integrity § | Thigh junction’s integrity due to the production of butyrate. | Altered intestinal permeability due to dysbiosis or emulsifiers’ effect. |

| Susceptibility to T1D or CD ¶ | Reduced susceptibility. | Increased susceptibility. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguayo-Patrón, S.V.; Calderón de la Barca, A.M. Old Fashioned vs. Ultra-Processed-Based Current Diets: Possible Implication in the Increased Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease in Childhood. Foods 2017, 6, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6110100

Aguayo-Patrón SV, Calderón de la Barca AM. Old Fashioned vs. Ultra-Processed-Based Current Diets: Possible Implication in the Increased Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease in Childhood. Foods. 2017; 6(11):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6110100

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguayo-Patrón, Sandra V., and Ana M. Calderón de la Barca. 2017. "Old Fashioned vs. Ultra-Processed-Based Current Diets: Possible Implication in the Increased Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease in Childhood" Foods 6, no. 11: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6110100

APA StyleAguayo-Patrón, S. V., & Calderón de la Barca, A. M. (2017). Old Fashioned vs. Ultra-Processed-Based Current Diets: Possible Implication in the Increased Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease in Childhood. Foods, 6(11), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6110100