Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Fructan Polysaccharides from Two Varieties of Codonopsis pilosulae (C. pilosula Nannf. var. modesta and C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

2.2. Polysaccharide Extraction, Separation, and Purification

2.3. Structural Analysis of WCP and BCP

2.3.1. Determination of Molecular Weight (Mw)

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Full-Wavelength UV Spectroscopy

2.3.3. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

2.3.4. Methylation Assay

2.3.5. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.3.7. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

2.4. WCP and BCP Immunological Activity Studies

2.4.1. Experimental Animals

2.4.2. Maximum Tolerable Dose Determination

2.4.3. Establishment of the NVB-Induced Immunodeficiency Model and Drug Administration

2.4.4. Neutrophil and Macrophage Counts

2.4.5. Inflammatory Cytokine Content Assay

2.4.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

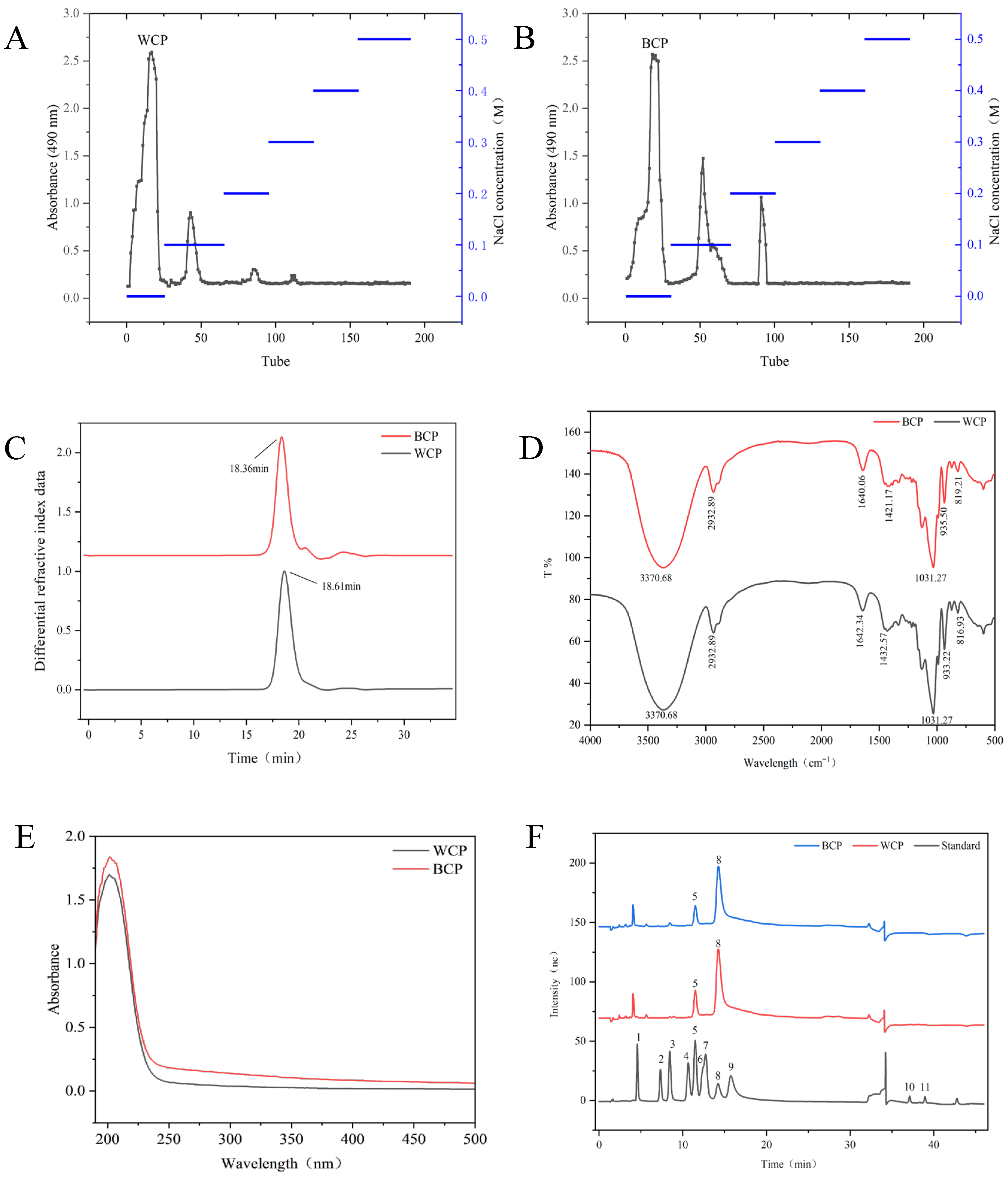

3.1. Extraction and Purification Analysis

3.2. Molecular Weight Analysis

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Ultraviolet Spectroscopy

3.4. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

3.5. Methylation Analysis

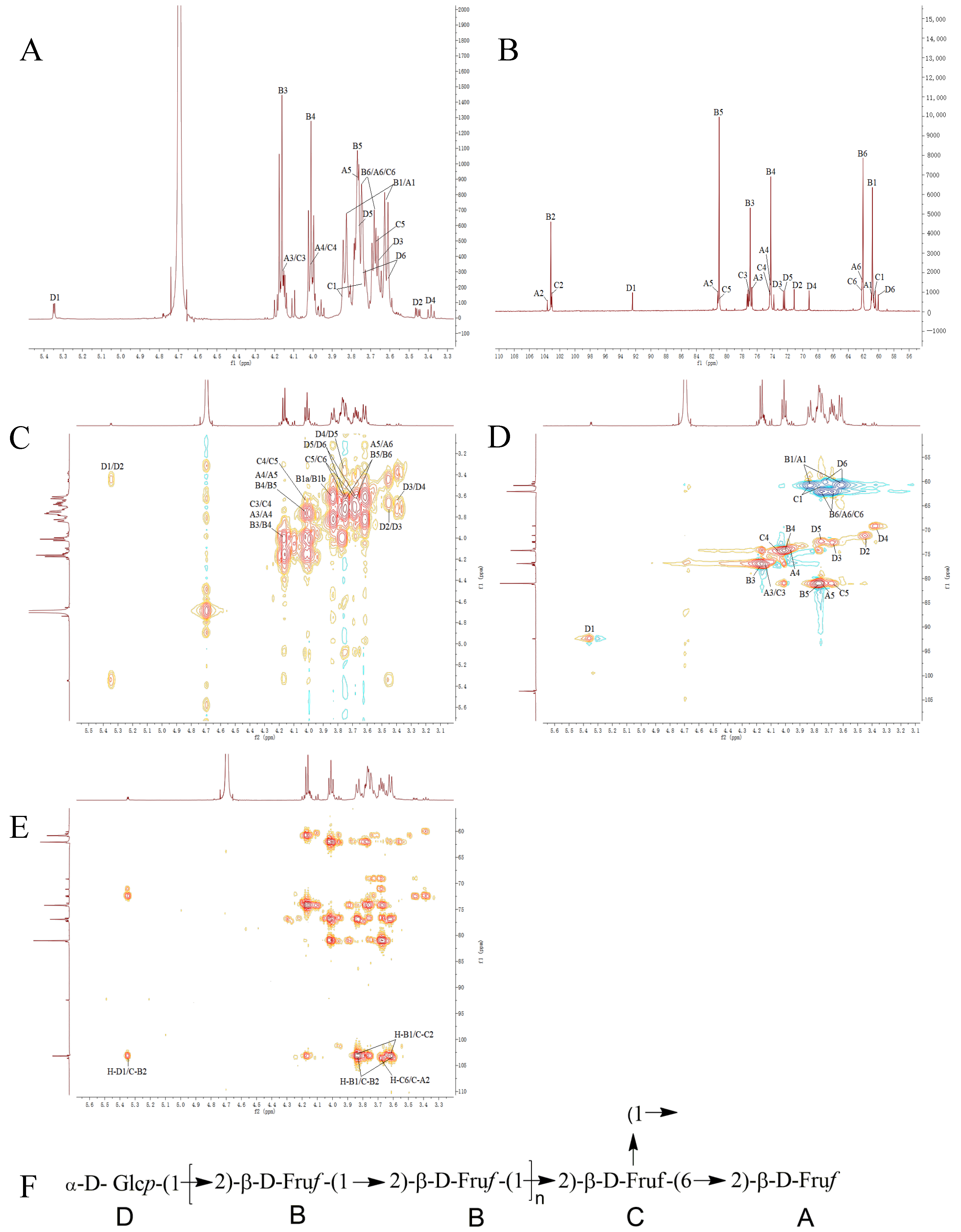

3.6. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis

3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.8. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.9. Immunological Activity Studies

3.9.1. Maximum Tolerated Concentration Determination

3.9.2. Effects of WCP and BCP on Neutrophil and Macrophage Counts

3.9.3. Inflammatory Cytokine Levels

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| CP | Codonopsis pilosula |

| WD | Codonopsis pilosula Nannf. var. modesta (Nannf.) L.T.Shen |

| BTD | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. |

| WCP | Codonopsis pilosula Nannf. var. modesta (Nannf.) L.T.Shen pure polysaccharides |

| BCP | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf pure polysaccharides |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| Mw | Molecular weight |

| Fuc | Fucose |

| Rha | Rhamnose |

| Ara | Arabinose |

| Gal | Galactose |

| Glc | Glucose |

| Man | Mannose |

| Xyl | Xylose |

| Fru | Fructose |

| Rib | Ribose |

| GalA | Galacturonic acid |

| GlcA | Gluconic acid |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| UV | Ultraviolet–Visible |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffractometer |

| NVB | Vinorelbine |

| LH | Levamisole hydrochloride |

References

- Yue, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, W. Insights into genus Codonopsis: From past Achievements to Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 3345–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; Ji, Y.; Peng, L.; Liu, Q.; Cao, H.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Zeng, N. Extraction, purification, structural characteristics and biological properties of the polysaccharides from Codonopsis pilosula: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.X.; Su, Y.J.; Wang, M.; Xi, J.Y.; Yang, F.; Li, F. Review of Codonopsis Radix biological activities: A plant of traditional Chinese tonic. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 332, 118334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.B.; Zhang, J.J.; Cao, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.X.; Yan, Q.; Li, X.; Li, C.N.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, F.D. Multi-element analysis of three Codonopsis Radix varieties in China and its correlation analysis with environmental factors. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 104, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.Y.; Hou, X.Y.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, Z.D.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Zhan, Z.L.; Nan, T.G.; Hao, Q.X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Discrimination of the species and origins of Codonopsis Radix by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS and UPLC-ELSD-based metabolomics combined with chemometrics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 139, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, S.X.; Hong, X.; Jin, H.; Huang, F.; Yang, Z.S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, G. Immunoenhancement effects of pentadecapeptide derived from Cyclina sinensis on immune-deficient mice induced by cyclophosphamide. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 60, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.C.; Yang, J.G.; Tang, Y.Q.; Xia, X.L.; Lin, J.X. Carboxymethyl polysaccharides from Poria cocos (Schw.) wolf: Structure, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, tumor cell proliferation inhibition and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 299, 140104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, R.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Kan, J.Q. Hovenia dulcis (Guaizao) polysaccharide ameliorates hyperglycemia through multiple signaling pathways in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 285, 138338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.J.; Song, M.K.; Wang, C.Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. Structural characterization of polysaccharide purified from Hericium erinaceus fermented mycelium and its pharmacological basis for application in Alzheimer’s disease: Oxidative stress related calcium homeostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, L.H.; Bai, R.B.; Zheng, X.P.; Ma, Y.L.; Gao, X.; Sun, B.L.; Hu, F.D. Structural characterization of a pectic polysaccharide from Codonopsis pilosula and its immunomodulatory activities in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, S.; Akyuz, S.; Ozel, A.E. Structural and vibrational investigations and molecular docking studies of a vinca alkoloid, vinorelbine. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 9666–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omar, A.; Asadi, M.; Mert, U.; Muftuoglu, C.; Karakus, H.S.; Goksel, T.; Caner, A. Effects of Vinorelbine on M2 Macrophages in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, S.A.; Loynes, C.A.; Trushell, D.M.; Elworthy, S.; Ingham, P.W.; Whyte, M.K. A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood 2006, 108, 3976–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellett, F.; Pase, L.; Hayman, J.W.; Andrianopoulos, A.; Lieschke, G.J. Mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood 2011, 117, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Paulsen, B.S.; Rise, F.; Chen, Z.L.; Jia, R.Y.; Li, L.X.; Song, X.; Feng, B.; Tang, H.Q.; et al. Structural features of pectic polysaccharides from stems of two species of Radix Codonopsis and their antioxidant activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, X.X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.R.; Li, J.; Chen, C.Y.; Liu, J.M.; Zheng, J.H.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.Z.; et al. Structural characteristics of Brassica rapa L. Polysaccharide and its bioactivity on alcoholic liver injury. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2025, 120, 107505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalasmeh, A.A.; Berhe, A.A.; Ghezzehei, T.A. A new method for rapid determination of carbohydrate and total carbon concentrations using UV spectrophotometry. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 97, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Yan, S.; Yang, L.; Song, H.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, H.; et al. Effect of microwave-assisted acid extraction on the physicochemical properties and structure of soy hull polysaccharides. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 6744–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.Q.; Ma, Y.L.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.Q. Structural characterization of cell-wall polysaccharides purified from chayote (Sechium edule) fruit. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Qu, H.; Shan, S.; Song, C.; Baranenko, D.; Li, Y.Z.; Lu, W.H. A novel polysaccharide isolated from Ulva Pertusa: Structure and physicochemical property. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 233, 115849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Wang, W.D.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.C.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Liu, B. Immune regulation mechanism of Saposhnikoviae Radix polysaccharide based on zebrafish model. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2022, 48, 1916–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.H.; Hawkins, C.L. Role of macrophage extracellular traps in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, I.; Motohashi, H.; Dallenga, T.; Schaible, U.E.; Benhar, M. Redox signaling in innate immunity and inflammation: Focus on macrophages and neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Fan, H.; Sun, M.; Li, J.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Liu, B. Chemical structure and immunomodulatory activity of a polysaccharide from Saposhnikoviae Radix. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Sun, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.F.; Tu, G.Z.; Liu, K.C.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Liu, B. Structure characterization and immunomodulatory activity of a polysaccharide from Saposhnikoviae Radix. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.T.; Zhu, H.; Jia, S.S.; Ma, K.; Yi, X.; Liu, T.Y.; Fan, J.H.; Hu, D.J.; Lv, G.P.; Huang, H. Isolation, purification, and structural characterization of polysaccharides from Codonopsis pilosula and its therapeutic effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.C.; Zhou, X.Y.; Shu, Z.H.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, X.L.; Zhang, P.Y.; Huang, H.T.; Sheng, L.L.; Zhang, P.S.; Wang, Q.; et al. Regulation strategy, bioactivity, and physical property of plant and microbial polysaccharides based on molecular weight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijak, M.; Saluk, J.; Tsirigotis, M.M.; Komorowska, H.; Wachowicz, B.; Zaczyńska, E.; Czarny, A.; Czechowski, F.; Nowak, P.; Pawlaczyk, I. The influence of conjugates isolated from Matricaria chamomilla L. on platelets activity and cytotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 61, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.D.; Yang, D.J.; Tan, H.J.; Zhan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, G. Optimization extraction, structural features and antitumor activity of polysaccharides from Z. jujuba cv. Ruoqiangzao seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhi, X.Y.; Sun, J.M.; Li, Y.R.; Tao, L.; Xiong, B.Y.; Lan, W.F.; Yu, L.; Song, S.X.; Zhou, Y.H. Structural characterization of two polysaccharides from Gastrodia elata Blume and their neuroprotective effect on copper exposure-induced HT-22 cell damage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 144019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, S. Effects of separation and purification on structural characteristics of polysaccharide from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa willd). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 522, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhao, X.T.; Fang, L.L.; Yang, T.; Xie, J.B. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of Platycodon grandiflorum polysaccharides and evaluation of its structural, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activity. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2023, 100, 106635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, I.M.; Carnachan, S.M.; Bell, T.J.; Hinkley, S.F.R. Methylation analysis of polysaccharides: Technical advice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Chen, H.L.; Luo, L.; Zhou, Z.P.; Wang, Y.X.; Gao, T.Y.; Yang, L.; Peng, T.; Wu, M.Y. Structures of fructan and galactan from Polygonatum cyrtonema and their utilization by probiotic bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.L.; Zhu, L.X.; Li, Y.X.; Cui, Y.S.; Jiang, S.L.; Tao, N.; Chen, H.B.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, C.X. A novel inulin-type fructan from Asparagus cochinchinensis and its beneficial impact on human intestinal microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Xu, C.Y.; Xia, J.; Feng, Y.N.; Zhang, X.F.; Yan, Y.Y. Extraction of polysaccharides from Codonopsis pilosula by fermentation with response surface methodology. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 6660–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.S.; Xu, F.J.; Yao, L.; Gao, Z.F.; Liu, S.Y.; Wang, H.S.; Lu, S.Q.; He, D.; Wang, L.W.; Zhang, L.F.; et al. End-to-End crystal structure prediction from powder X-Ray diffraction. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2410722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabelsi, I.; Ben, S.S.; Ktari, N.; Bouaziz, M.; Salah, R.B. Structure analysis and antioxidant activity of a novel polysaccharide from Katan seeds. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6349019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Jiang, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Ping, W.X.; Ge, J.P. Characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by Weissella confusa XG-3 and their potential biotechnological applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 178, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosowski, E.E. Determining macrophage versus neutrophil contributions to innate immunity using larval zebrafish. Dis. Models Mech. 2020, 13, 041889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, G.L.; Foti, A.; Marsman, G.; Patel, D.F.; Zychlinsky, A. The Neutrophil. Immunity 2021, 54, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Liu, R.; Li, Q.; Xu, H.; Cai, M.; Guan, R.; Sun, P.; Yang, K. Dual-immunomodulatory effects on RAW264.7 macrophages and structural elucidation of a polysaccharide isolated from fermentation broth of Paecilomyces hepiali. J. Future Foods 2025, 5, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujal, A.M.; Owyong, M.; Santosa, E.K.; Sauter, J.C.; Grassmann, S.; Pedde, A.M.; Meiser, P. Splenic TNF-α signaling potentiates the innate-to-adaptive transition of antiviral NK cells. Immunity 2025, 58, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasgur, S.; Fan, R.; Zwick, D.B.; Fairchild, R.L.; Valujskikh, A. B cell-derived IL-1β and IL-6 drive T cell reconstitution following lymphoablation. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 2740–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Shu, Q. Modulating butyric acid-producing bacterial community abundance and structure in the intestine of immunocompromised mice with neutral polysaccharides extracted from Codonopsis pilosula. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Methylated Fragments | Major Fragment Mass | Glycosidic Bond Linkage Type | Mole Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCP | BCP | ||||

| 1 | 1,3,5,6-Me4-Manf/Glcf | 87, 101, 129, 145, 161 | Fruf-(2→ | 0.111 | 0.154 |

| 2 | 2,3,4,6-Me4-Glcp | 43, 71, 87, 101, 117, 129, 145, 161, 205 | Glcp-(1→ | 0.106 | 0.128 |

| 3 | 1,3,5-Me2-Manf/Glcf | 99, 129, 145, 161, 189 | →6)Fruf-(2→ | 0 | 0.009 |

| 4 | 3,5,6-Me3-Manf/Glcf | 43, 71, 87, 99, 101, 129, 145, 161, 189 | →1)-Fruf-(2→ | 0.777 | 0.696 |

| 5 | 3,5-Me2-Manf/Glcf | 43, 87, 99, 129, 159, 189, 233 | →1,6)Fruf-(2→ | 0.006 | 0.014 |

| Code | Glycosyl Residues | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.83, 3.62 | 4.16 | 4.00 | 3.76 | 3.73, 3.68 | |

| C | 60.97 | 103.63 | 76.70 | 74.31 | 81.80 | 62.19 | ||

| B | →1)-β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.83, 3.62 | 4.17 | 4.01 | 3.77 | 3.73, 3.68 | |

| C | 60.83 | 103.18 | 76.92 | 74.21 | 81.01 | 62.06 | ||

| C | →1,6)-β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.83, 3.75 | 4.16 | 4.00 | 3.68 | 3.73, 3.68 | |

| C | 60.65 | 103.08 | 77.22 | 74.35 | 80.02 | 62.22 | ||

| D | α-D- Glcp-(1→ | H | 5.35 | 3.45 | 3.65 | 3.38 | 3.73 | 3.72, 3.61 |

| C | 92.42 | 71.13 | 72.54 | 69.17 | 72.38 | 60.05 |

| Code | Glycosyl Residues | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.81, 3.61 | 4.15 | 4.02 | 3.75 | 3.73, 3.66 | |

| C | 60.43 | 103.63 | 76.70 | 74.22 | 81.20 | 62.08 | ||

| B | →1)-β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.81, 3.61 | 4.17 | 4.01 | 3.76 | 3.73, 3.66 | |

| C | 60.84 | 103.18 | 76.93 | 74.22 | 81.03 | 62.08 | ||

| C | →1,6)-β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.83, 3.71 | 4.15 | 4.02 | 3.67 | 3.73, 3.66 | |

| C | 60.07 | 103.09 | 76.93 | 73.81 | 81.20 | 62.08 | ||

| D | →6)-β-D-Fruf-(2→ | H | 3.81, 3.61 | 4.16 | 4.01 | 3.76 | 3.73, 3.66 | |

| C | 60.97 | 103.03 | 77.23 | 74.22 | 81.80 | 62.08 | ||

| E | α-D- Glcp-(1→ | H | 5.34 | 3.44 | 3.68 | 3.38 | 3.74 | 3.71, 3.60 |

| C | 92.43 | 71.14 | 72.39 | 69.17 | 72.17 | 60.07 |

| Concentration (mg/mL) | WCP Mortality (%) | BCP Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3.2 | 20 | 10 |

| 4.0 | 50 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; Bai, X.; Wu, Z.; Ma, X.; Jin, X.; Fan, B.; Wang, F.; Sun, J. Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Fructan Polysaccharides from Two Varieties of Codonopsis pilosulae (C. pilosula Nannf. var. modesta and C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf.). Foods 2026, 15, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030495

Dong J, Bai X, Wu Z, Ma X, Jin X, Fan B, Wang F, Sun J. Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Fructan Polysaccharides from Two Varieties of Codonopsis pilosulae (C. pilosula Nannf. var. modesta and C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf.). Foods. 2026; 15(3):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030495

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jingjing, Xue Bai, Ziyang Wu, Xinxin Ma, Xiaoping Jin, Bei Fan, Fengzhong Wang, and Jing Sun. 2026. "Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Fructan Polysaccharides from Two Varieties of Codonopsis pilosulae (C. pilosula Nannf. var. modesta and C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf.)" Foods 15, no. 3: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030495

APA StyleDong, J., Bai, X., Wu, Z., Ma, X., Jin, X., Fan, B., Wang, F., & Sun, J. (2026). Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Fructan Polysaccharides from Two Varieties of Codonopsis pilosulae (C. pilosula Nannf. var. modesta and C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf.). Foods, 15(3), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030495