Proanthocyanidins from Camellia kwangsiensis with Potent Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedure

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Materials

2.4. Extraction Procedures

2.5. HPLC and LC-MS Method

2.6. Quantitative Determination

2.7. Extraction and Isolation

2.8. Compound 1

2.9. Thiol Degradation

2.10. Antioxidant Assay

2.11. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Assay

2.12. Anti-Inflammatory Assay

2.13. Data Presentation

3. Results and Discussion

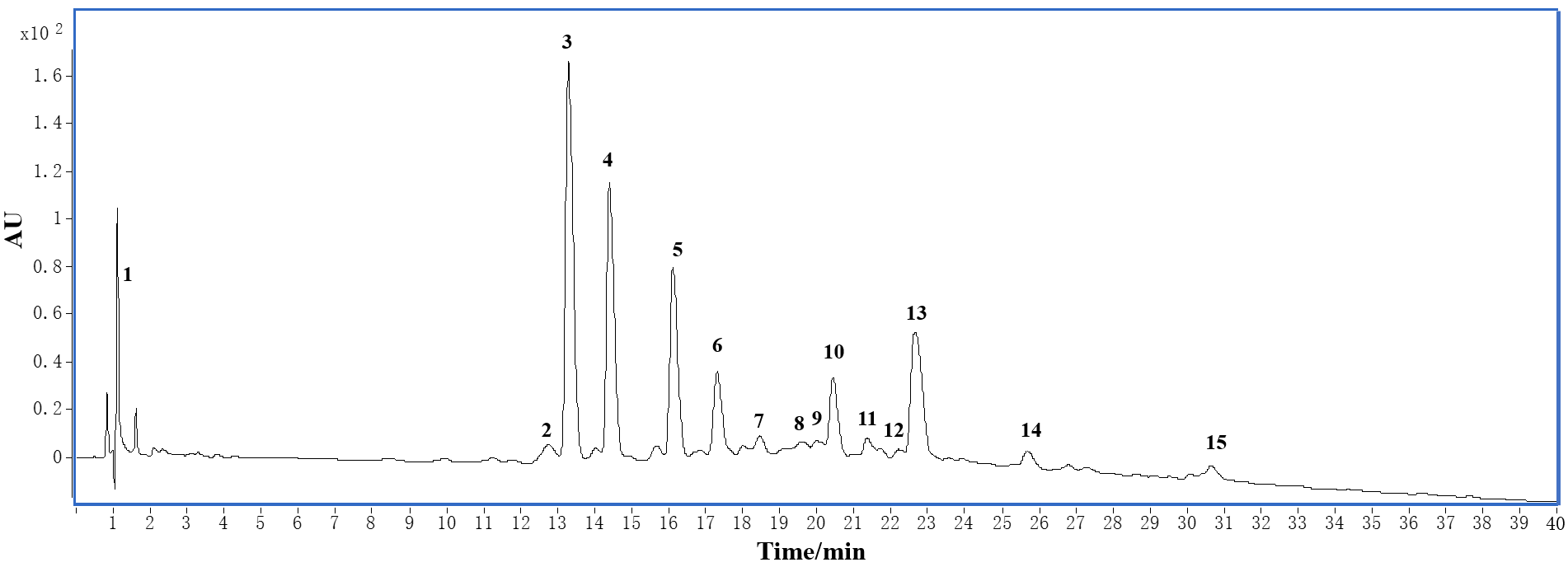

3.1. HPLC and LC-MS Analysis

3.2. Simultaneous Quantification of Five Main Compositions

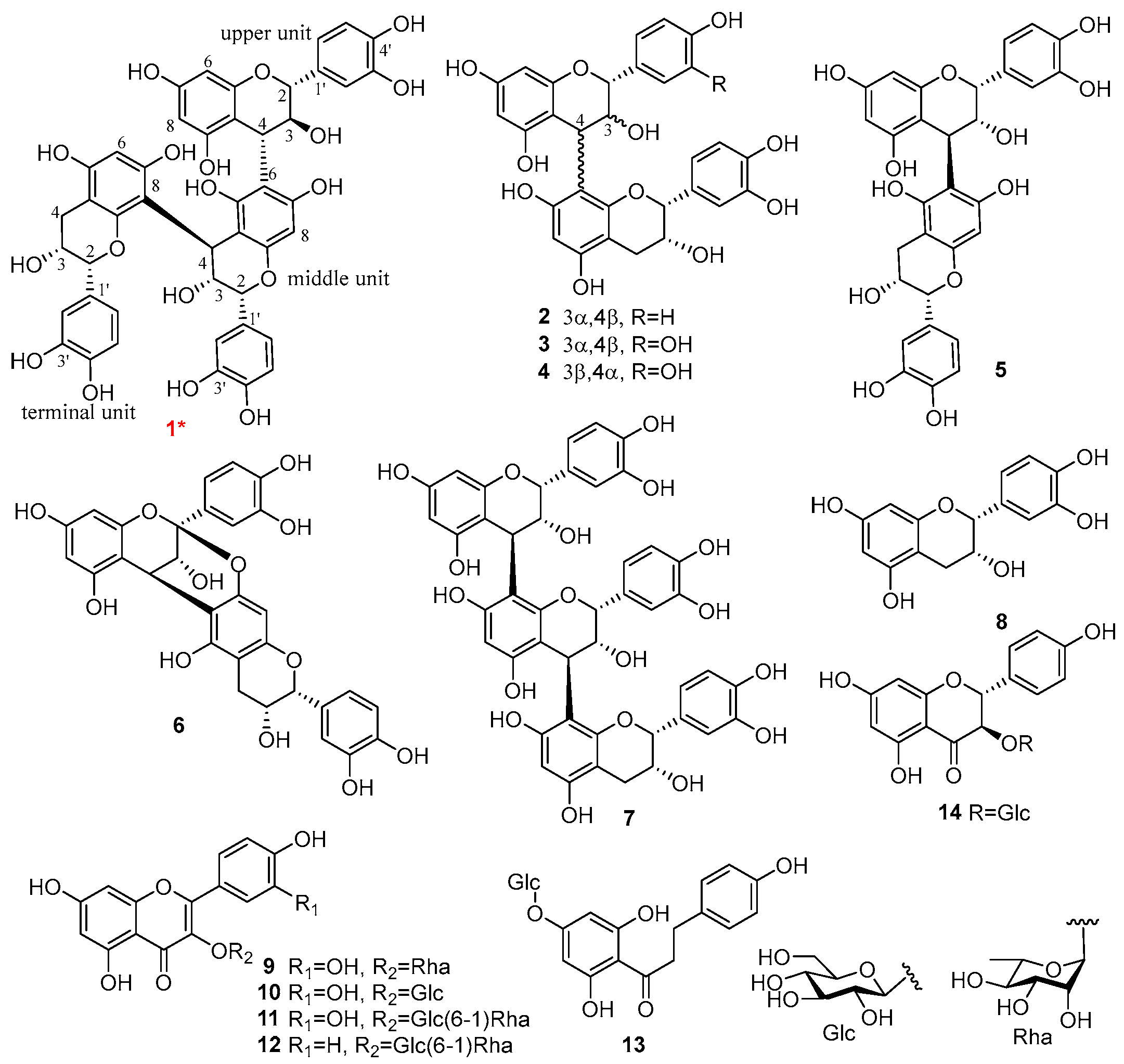

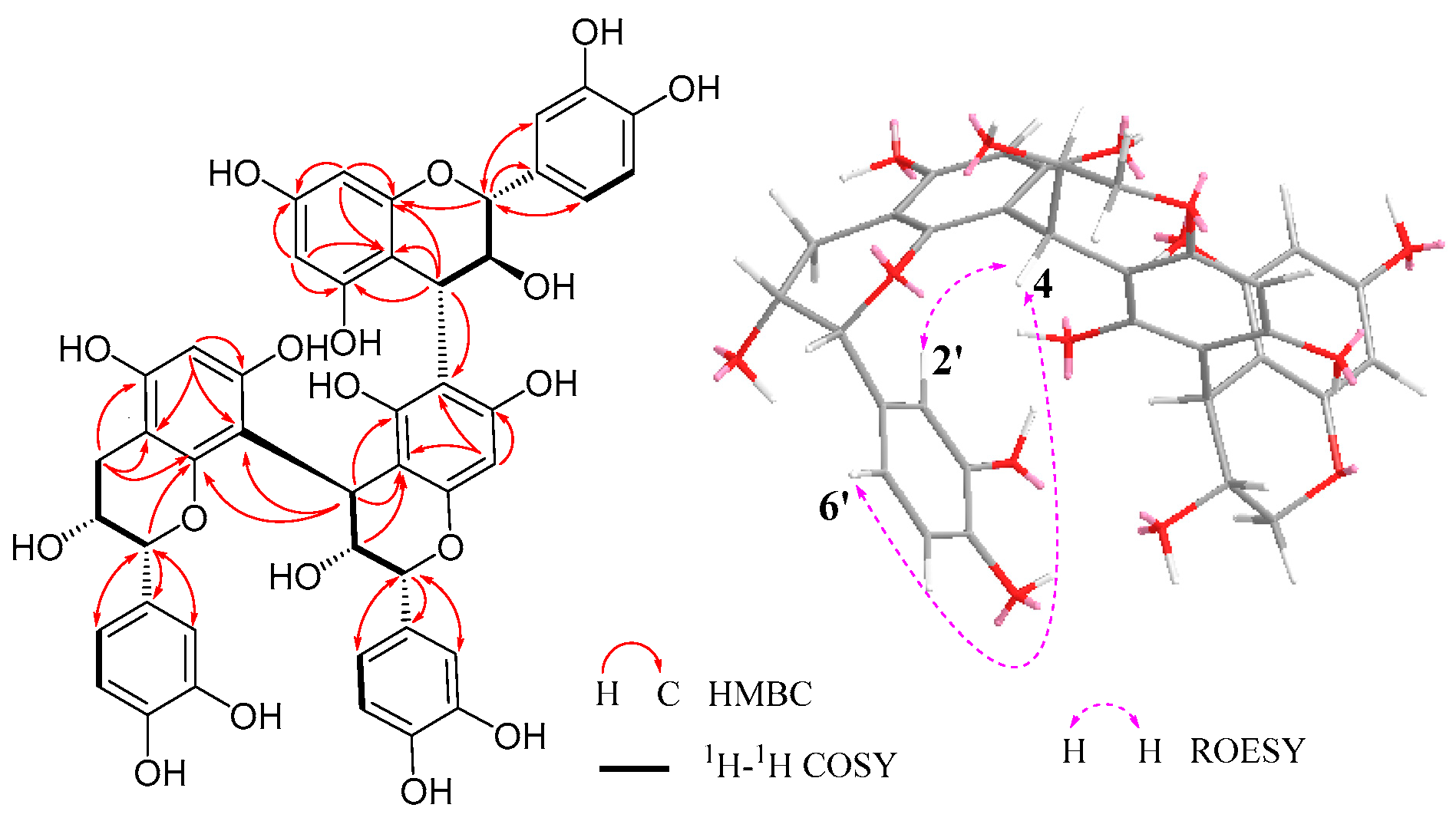

3.3. Identification of Compounds 1–19

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

3.6. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, X.H.; Li, N.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. Plant resources, chemical constituents, and bioactivities of tea plants from the genus Camellia section Thea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5318–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tao, W.; Li, L.; Wei, C.; Duan, J.; Chen, S.; Ye, X. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of proanthocyanidins from Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) leaves. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 27, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.A.; Pimentel, F.; Costa, A.S.G.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Cardioprotective properties of grape seed proanthocyanidins: An update. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Mukhtar, H. Tea Polyphenols in Promotion of Human Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlier, N.; Gokcen, B.B.; Altuğ, M. Tea consumption and disease correlations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellstrom, J.K.; Torronen, A.R.; Mattila, P.H. Proanthocyanidins in common food products of plant origin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7899–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Liu, H.M.; Ma, Y.X.; Wang, X.D. Chapter 9—Developments in extraction, purification, and structural elucidation of proanthocyanidins (2000–2019). In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 68, pp. 347–391. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt, U.H.; Lakenbrink, C.; Pokorny, O. Proanthocyanidins, bisflavanols, and hydrolyzable tannins in green and black teas. In Nutraceutical Beverages. Chemistry, Nutrition, and Health Effects; Shahidi, F., Weerasinghe, D.K., Eds.; ACS Symposium: Washingtong DC, USA, 2003; Volume 871, pp. 254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Deng, H.; Qu, H.; Zhang, B.; Lei, G.; Chen, J.; Feng, X.; Wu, D.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Z. Penicillium simplicissimum possessing high potential to develop decaffeinated Qingzhuan tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 165, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ku, K.M. Biomarkers-based classification between green teas and decaffeinated green teas using gas chromatography mass spectrometer coupled with in-tube extraction (ITEX). Food Chem. 2019, 271, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Ou, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ying, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Tan, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Scenting: An effective processing technology for enriching key flavor compounds and optimizing flavor quality of decaffeinated tea. Food Chem. 2025, 467, 142372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G. Scenting: Development of biomaterials based on plasticized polylactic acid and tea polyphenols for active-packaging application. Int. J. Biol. Marcromol. 2022, 217, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, S.; Dai, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Peng, X.; Xie, X.; Peng, C. Molecular mechanisms and applications of tea polyphenols: A narrative review. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, 13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shao, J.; Pang, Y.; Wen, C.; Wei, K.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X. Antidiabetic potential of tea and its active compounds: From molecular mechanism to clinical evidence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11837–11853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.F.; Xu, M.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, S.X.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. New flavan-3-ol dimer from green tea produced from Camellia taliensis in the Ai-Lao mountains of Southwest China. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 12170–12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. New flavoalkaloids with potent α-glucosidase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities from Yunnan black tea ‘Jin-Ya’. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7955–7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Kong, Q.H.; Kong, L.M.; Yan, B.C.; Yang, L.; Zhu, H.T.; Zhang, Y.J. Bio-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory compounds from Tilia tuan Szyszyl. flowers via in vitro and in silico study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, B. LC-MS identification of proanthocyanidins in bark and fruit of six Terminalia species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwada, Y.; Iizuka, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Chen, R.F.; Nonaka, G.I.; Nishioka, I. Tannins and related compounds. XCIII. Occurrence of enantiomeric proanthocyanidins in the Leguminosae plants, Cassia fistula L. and C. javanica L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990, 38, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Mutsuga, M.; Nakamura, T.; Kanda, T.; Akiyama, H.; Goda, Y. Isolation and structural elucidation of some procyanidins from apple by low-temperature nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3806–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, N.; Saito, A.; Tanaka, A.; Ubukata, M. Synthetic studies of proanthocyanidins. Part 4. The synthesis of procyanidin B1 and B4: TMSOTf-catalyzed cyclization of catechin and epicatechin condensation. Heterocycles 2003, 61, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, T.; Bareuther, S.; Hofmann, T. Sensory-guided decomposition of roasted cocoa nibs (Theobroma cacao) and structure determination of taste-active polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5407–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K.; Watanabe, C.; Endang, H.; Umar, M.; Satake, T. Studies on the constituents of bark of Parameria laevigata moldenke. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Liu, Y.Q.; Li, X.C.; Yang, C.R. Chemical constituents of “Ecological Tea” from Yunnan. Acta Bot. Yunnanica 1995, 17, 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; ElSohly, H.N.; Li, X.C.; Khan, S.I.; Broedel, S.E.; Raulli, R.E.; Cihlar, R.L.; Burandt, C.; Walker, L.A. Phenolic compounds from Nymphaea odorata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuma, K.; Noda, N.; Suzuki, M. Malonylated flavonol glycosides from the petals of Clitoria ternatea. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.D.; Liu, J.K. A new sweet dihydrochalcone-glucoside from leaves of Lithocarpus pachyphyllus (Kurz) Rehd. (Fagaceae). Z. Naturforsh. C 2003, 58, 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gödecke, T.; Kaloga, M.; Kolodziej, H. A phenol glucoside, uncommon coumarins and flavonoids from Pelargonium sidoides DC. J. Chem. Sci. 2005, 60, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.W.; Zhao, P.J.; Ma, Y.L.; Xiao, H.T.; Zuo, Y.Q.; He, H.P.; Li, L.; Hao, X.J. Mixed lignan-neolignans from Tarenna attenuata. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, M.L.; Robles, C.J.; Erra-Balsells, R. Photoisomerization of ionic liquid ammonium cinnamates: One-pot synthesis-isolation of Z-cinnamic acids. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4808–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, N.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Begum, S.; Ali, M.I.; Marasini, B.P.; Khan, A.; Choudhary, M.I. Bioassay-guided isolation of urease and α-chymotrypsin inhibitory constituents from the stems of Lawsonia alba Lam. (Henna). Fitoterapia 2013, 84, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzini, T.; Botta, G.; Delfino, M.; Onofri, S.; Saladino, R.; Amatore, D.; Sgarbanti, R.; Nencioni, L.; Palamara, A.T. Tyrosinase and Layer-by-Layer supported tyrosinases in the synthesis of lipophilic catechols with antiinfluenza activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 7699–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, T.; Suga, K.; Sato, K.; Sato, Y. A strained disilane-promoted carboxylation of organic halides with CO2 under transition-metal-free conditions. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5276–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esatbeyoglu, T.; Jaschok-Kentner, B.; Wray, V.; Winterhalter, P. Structure elucidation of procyanidin oligomers by low-temperature 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phansalkar, R.S.; Nam, J.W.; Leme-Kraus, A.A.; Gan, L.S.; Zhou, B.; Mcalpine, J.B.; Chen, S.N.; Bedran-Russo, A.K.; Paul, G.F. Proanthocyanidin dimers and trimers from Vitis vinifera provide diverse structural motifs for the evaluation of dentin biomodification. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Evans, F.J.; Roberts, M.F.; Phillipson, J.D.; Zenk, M.H.; Gleba, Y.Y. Polyphenolic compounds from Croton lechleri. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, R.; Kouno, I.; Nonaka, G.I. Chemical evidence for the de-astringency (insolubilization of tannins) of persimmon fruit. J. Chem. Sco.-Perkin Trans. 1994, 1, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.S.; Yu, S.J. Characterization of lipophilized monomeric and oligomeric grape seed flavan-3-ol derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8875–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, J.; Tian, J.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J. Inhibitory mechanism of novel allosteric inhibitor, Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) leaves proanthocyanidins against α-glucosidase. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, M.; Nieminen, R.; Vuorela, P.; Heinonen, M.; Moilanen, E. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids: Genistein, kaempferol, quercetin, and daidzein inhibit STAT-1 and NF-κB activations, whereas flavone, isorhamnetin, naringenin, and pelargonidin inhibit only NF-κB activation along with their inhibitory effect on iNOS expression and NO production in activated macrophages. Mediat. Inflamm. 2007, 2007, 45673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhol, N.K.; Bhanjadeo, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Dash, U.C.; Ojha, R.R.; Majhi, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Liu, C.; Fan, R.; Zhu, L.F.; Yang, S.X.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. Antioxidative flavan-3-ol dimer from the leaves of Camellia fangchengensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yang, C.R.; Xu, M. Phenolic antioxidants from green tea produced from Camellia crassicolumna var. multiplex. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zhu, H.T.; Yan, H.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. C-8 N-Ethyl-2-pyrrolidinone-substituted flavan-3-ols from the leaves of Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7150–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Position b | Upper Unit | Position b | Middle Unit | Position b | Terminal Unit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH (J, Hz) | δC | δH (J, Hz) | δC | δH (J, Hz) | |||

| 2 | 83.7 | 4.50 d (9.6) | 2 | 77.4 | 5.22 s | 2 | 79.9 | 5.00 s |

| 3 | 73.1 | 4.70 m | 3 | 73.3 | 3.94 br s | 3 | 67.0 | 4.31 br s |

| 4 | 39.2 | 4.75 d (8.2) | 4 | 37.3 | 4.73 d (1.6) | 4 | 29.8 | 2.97 dd (16.8, 4.6) 2.82 dd (16.8, 2.5) |

| 5 | 157.2 | 5 | 156.7 | 5 | 156.8 | |||

| 6 | 97.8 | 5.86 d (2.2) | 6 | 107.9 | 6 | 97.8 | 5.96, s | |

| 7 | 157.6 | 7 | 157.2 | 7 | 155.8 | |||

| 8 | 96.3 | 5.86 d (2.2) | 8 | 97.7 | 6.04, s | 8 | 107.6 | |

| 9 | 158.6 | 9 | 157.0 | 9 | 154.6 | |||

| 10 | 107.3 | 10 | 100.9 | 10 | 100.6 | |||

| 1′ | 132.2 | 1′ | 132.8 | 1′ | 132.2 | |||

| 2′ | 116.5 | 7.04 d (1.9) | 2′ | 115.1 | 7.00 d (1.7) | 2′ | 115.4 | 7.12 d (1.8) |

| 3′ | 146.6 | 3′ | 145.8 | 3′ | 146.0 | |||

| 4′ | 146.3 | 4′ | 145.5 | 4′ | 145.8 | |||

| 5′ | 116.3 | 6.83 d (8.0) | 5′ | 116.1 | 6.73 d (8.2) | 5′ | 116.1 | 6.77 d (8.0) |

| 6′ | 121.5 | 6.91 dd (8.0, 1.9) | 6′ | 118.8 | 6.65 dd (8.2, 1.7) | 6′ | 119.4 | 6.93 dd (8.0, 1.8) |

| Peak | tR/min | Positive MS | Positive MS2 | Negative MS | Negative MS2 | MW b | Compounds c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.38 | 215 [M + Na]+ | 191 [M − H]− 383 [2M − H]− | 192 | quinic acid | ||

| 2 | 12.83 | 601 [M + Na]+ | 409, 291, 289 | 577 [M − H]− | 425 [RDA]−, 407 [425 − H2O]−, 289 [C/EC]−, 287 | 578 | 4 |

| 3 | 13.36 | 601 [M + Na]+ | 409, 291, 289 | 577 [M − H]− | 425 [RDA]−, 407 [425 − H2O]−, 289 [C/EC]−, 287 | 578 | 3 |

| 4 | 14.51 | 291 [M + H]+ | 289 [M − H]− | 245 [M−H−COO]− | 290 | 8 | |

| 5 | 16.11 | 867 [M + H]+ | 741 [M−phloroglucinol]+, 715 [RDA]+, 579, 427 [RDA]+, 291 [C/EC]+, 289, 245 | 865 [M − H]− | 866 | 7 | |

| 6 | 17.22 | not identified | |||||

| 7 | 18.57 | 633 [M + Na]+ | 609 [M − H]− | 301 [quercetin]− | 610 | 11 | |

| 8 | 19.63 | 487 [M + Na]+ | 463 [M − H]− | 301 [quercetin]− | 464 | 10 | |

| 9 | 20.05 | 487 [M + Na]+ | 325 | 463 [M − H]− | 301 [quercetin]− | 464 | quercetin 3-O-β-D-galactoside |

| 10 | 20.43 | 579 [M + H]+ | 409 [427 − H2O]+, 291, 289, 127 | 577 [M − H]− | 425 [RDA]−, 289 [C/EC]− | 578 | 5 |

| 11 | 21.53 | 595 [M + H]+ | 449 [M−rhamnosyl]+, 287 [kaempferol]+ | 593 [M − H]− | 415, 285 [kaempferol]−, 227, 185, 133 | 594 | 12 |

| 12 | 22.13 | 433 [M − H]− | 301 [quercetin]− | 434 | quercetin3-O-α-L-ara-binoside | ||

| 13 | 22.71 | 471 [M + Na]+ | 325, 87 | 447 [M − H]− | 301 [quercetin]−, 271, 244, 227, 197, 175, 145 | 448 | 9 |

| 14 | 25.74 | 455 [M + Na]+ | 431 [M − H]− | 285 [kaempferol]−, 227 | 432 | kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnoside | |

| 15 | 30.76 | 301 [M − H]− | 302 | quercetin |

| Sample | SC50 (μM) a | Sample | SC50 (μM) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH b | ABTS+ b | DPPH b | ABTS+ b | ||

| Ascorbic acid | 17.8 ± 0.3 | / | 7 | 10.4 ± 0.2 | 50.8 ± 5.1 |

| Trolox | / | 188.7 ± 0.1 | 8 | 30.1 ± 0.2 | 138.2 ± 4.8 |

| 1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 42.5 ± 3.2 | 9 | 28.2 ± 0.8 | 245.6 ± 5.1 |

| 2 | 16.8 ± 0.1 | 96.8 ± 2.6 | 10 | 26.7 ± 2.3 | 200.3 ± 5.3 |

| 3 | 11.3 ± 0.5 | 53.3 ± 2.8 | 11 | 38.5 ± 4.5 | 360.7 ± 4.2 |

| 4 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | 53.4 ± 1.9 | 12 | 45.7 ± 0.7 | 884.9 ± 3.5 |

| 5 | 11.0 ± 0.1 | 66.7 ± 0.3 | 13 | 32.4 ± 3.0 | 250.3 ± 3.2 |

| 6 | 14.9 ±0.1 | 122.6 ± 8.8 | 14 | 21.7 ± 1.4 | 135.1 ± 2.5 |

| Sample | IC50 (μM) b | Sample | Inhibition Ratio (%) c |

|---|---|---|---|

| quercetin f | 5.94 ± 0.2 | quercetin f | 63.5 ± 0.9 d |

| acarbose f | 223 ± 10 | acarbose f | 47.2 ± 1.2 e |

| 1 | 19.6 ± 0.4 | 3 | 20.9 ± 0.6 |

| 2 | 28.8 ± 0.8 | 8 | 53.0 ± 1.9 |

| 4 | 10.8 ± 0.3 | 9 | 41.4 ± 0.7 |

| 5 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 10 | 38.1 ± 1.0 |

| 6 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | 11 | 7.81 ± 0.50 |

| 7 | 20.1 ± 0.4 | 12 | 18.4 ± 0.6 |

| 13 | 34.0 ± 0.1 | ||

| 14 | 31.2 ± 3.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, N.; Ni, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.-T.; Zhang, M.; Tanaka, T.; Zhang, Y.-J. Proanthocyanidins from Camellia kwangsiensis with Potent Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Foods 2026, 15, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030442

Li N, Ni Q, Chen M, Zhu H-T, Zhang M, Tanaka T, Zhang Y-J. Proanthocyanidins from Camellia kwangsiensis with Potent Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Foods. 2026; 15(3):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030442

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Na, Qin Ni, Min Chen, Hong-Tao Zhu, Man Zhang, Takashi Tanaka, and Ying-Jun Zhang. 2026. "Proanthocyanidins from Camellia kwangsiensis with Potent Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity" Foods 15, no. 3: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030442

APA StyleLi, N., Ni, Q., Chen, M., Zhu, H.-T., Zhang, M., Tanaka, T., & Zhang, Y.-J. (2026). Proanthocyanidins from Camellia kwangsiensis with Potent Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Foods, 15(3), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030442