Influences of Fermentation Temperature on Volatile and Non-Volatile Compound Formation in Dark Tea: Mechanistic Insights Using Aspergillus niger as a Model Organism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Tea Samples

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

2.4. Determination of Major Quality Compounds

2.5. Determination of Catechins, Gallic Acid, Caffeine

2.6. Detection of the Volatile Compounds

2.7. Calculation of Odor Activity Value

2.8. Detection of the Non-Volatile Compounds

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inoculation with AN at 25–37 °C Contributes to Form the Sensory Quality of Dark Tea

3.2. Dynamic Change in Major Quality Compounds at Different Fermentation Temperatures

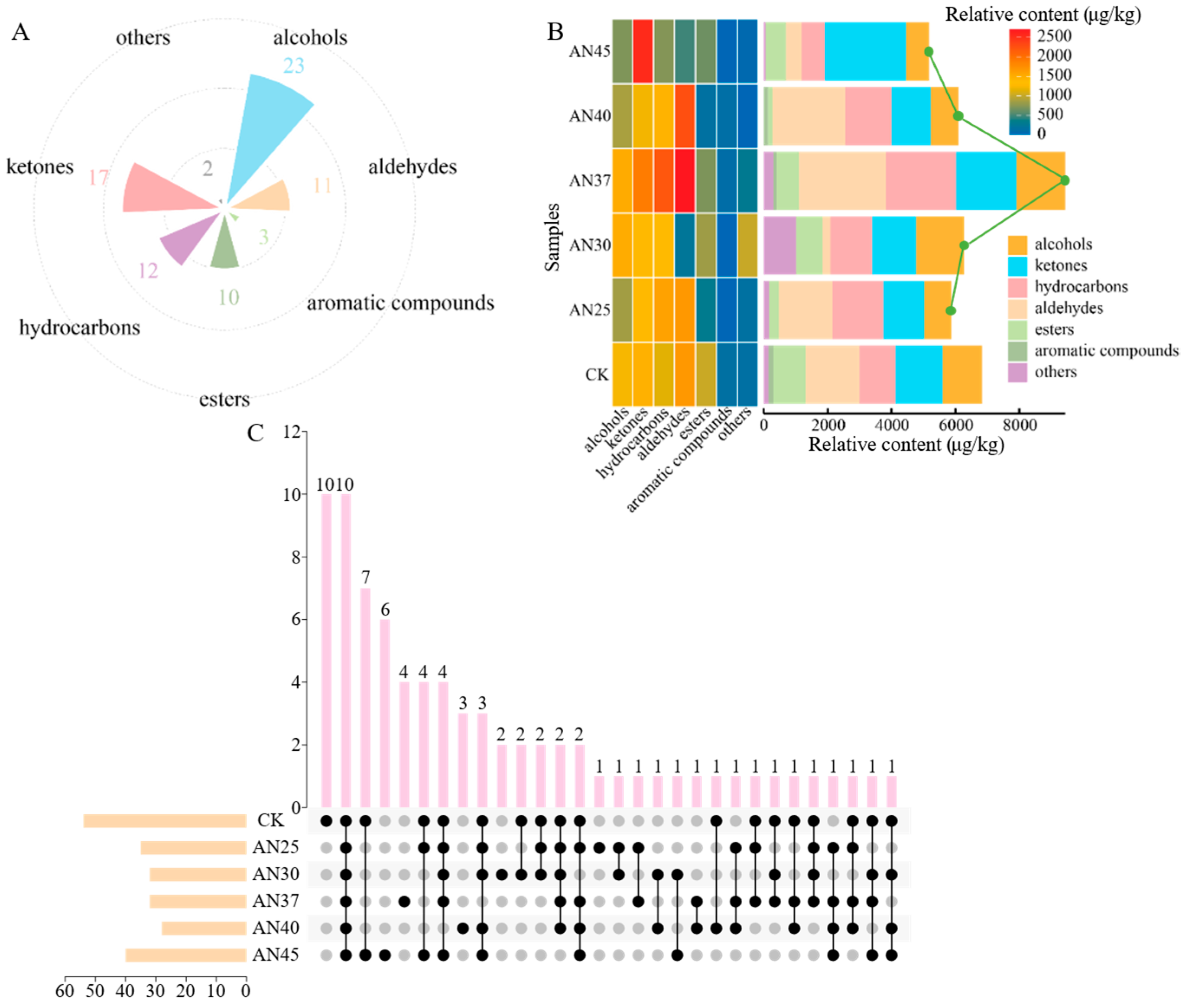

3.3. Inoculation with AN at Different Fermentation Temperatures Impacts the Composition of Volatile Compounds in Dark Tea

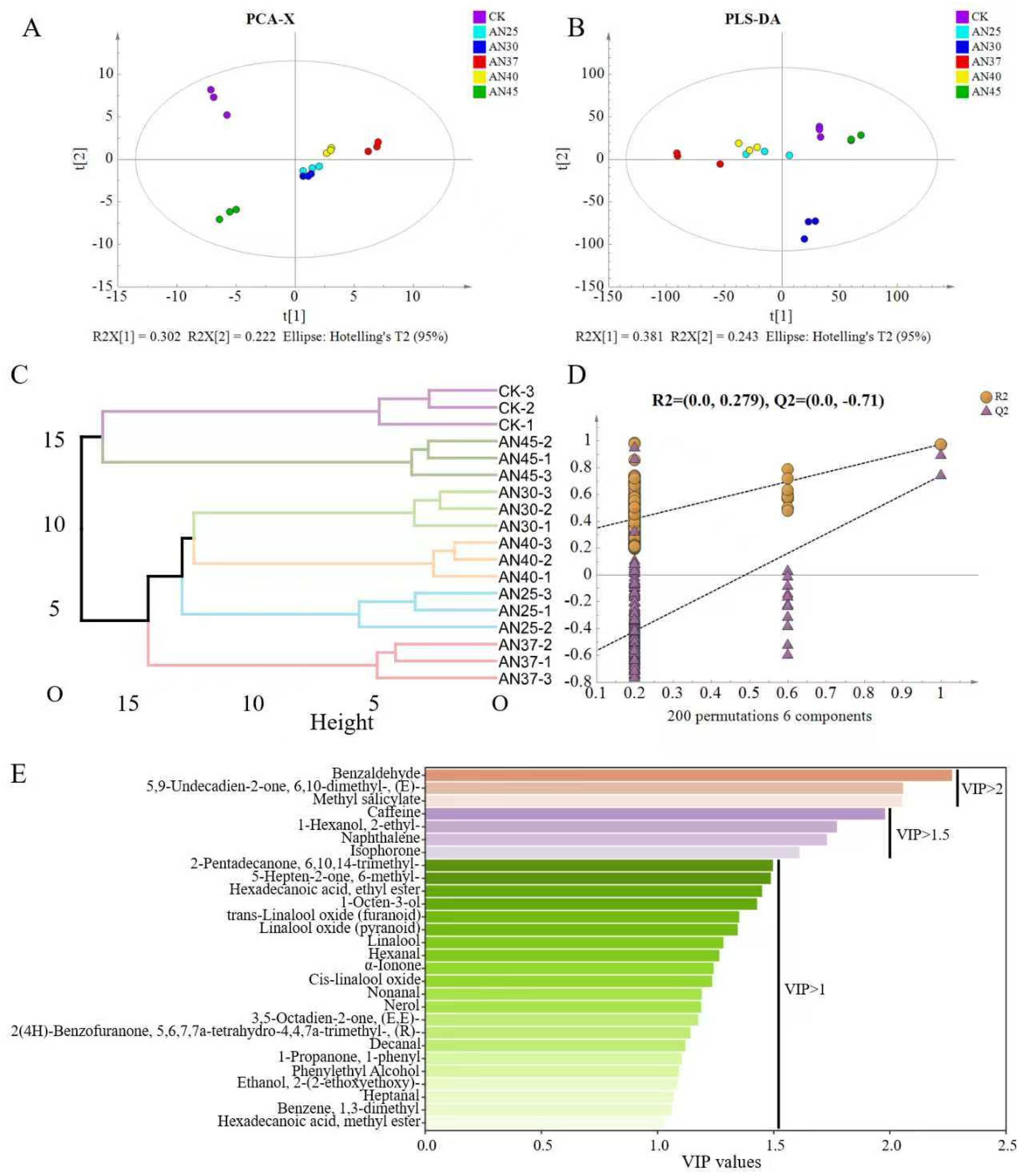

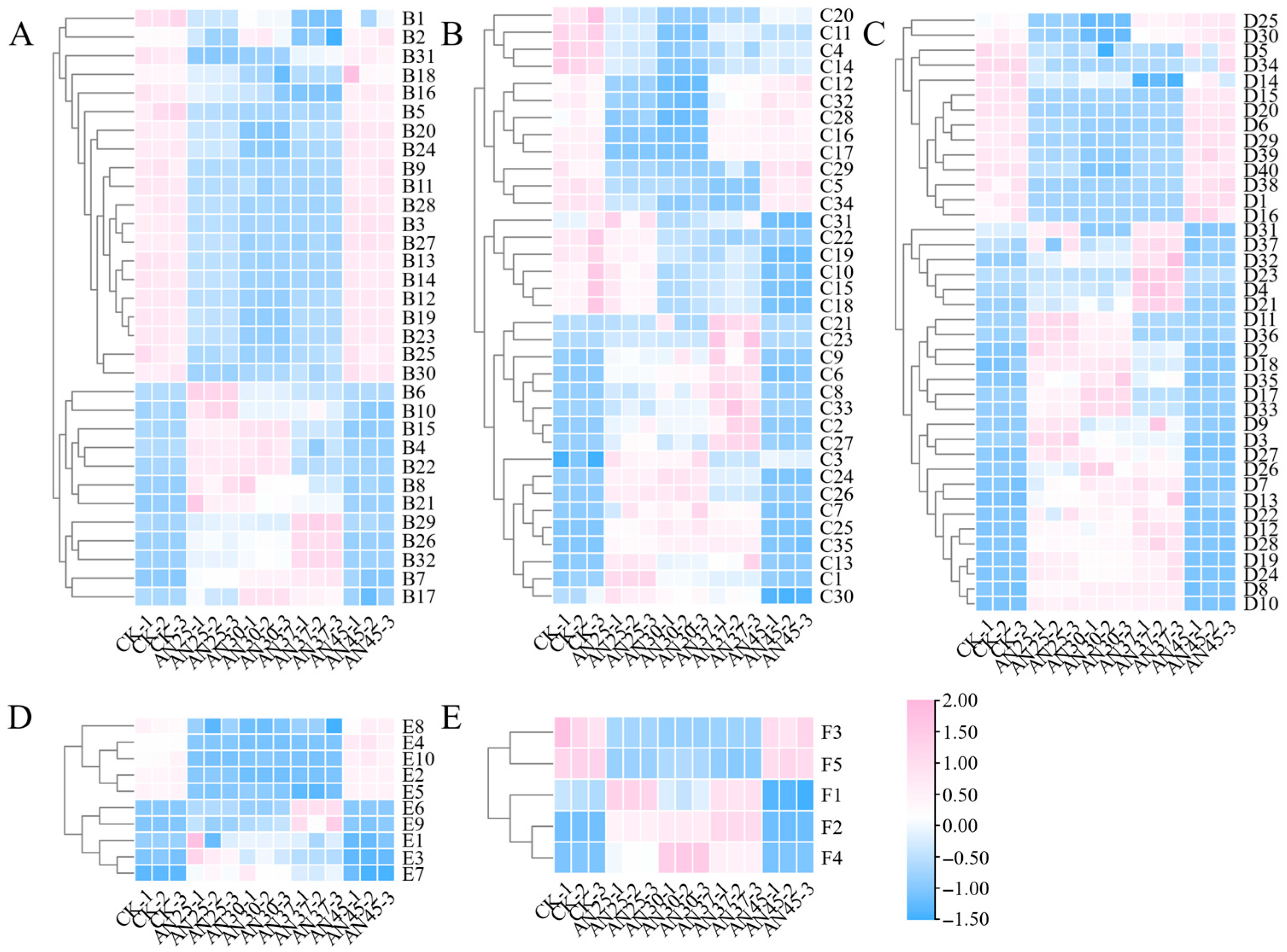

3.4. The Difference in Volatiles at Different Fermentation Temperatures

3.5. Key Volatiles in Tea at Different Fermentation Temperatures

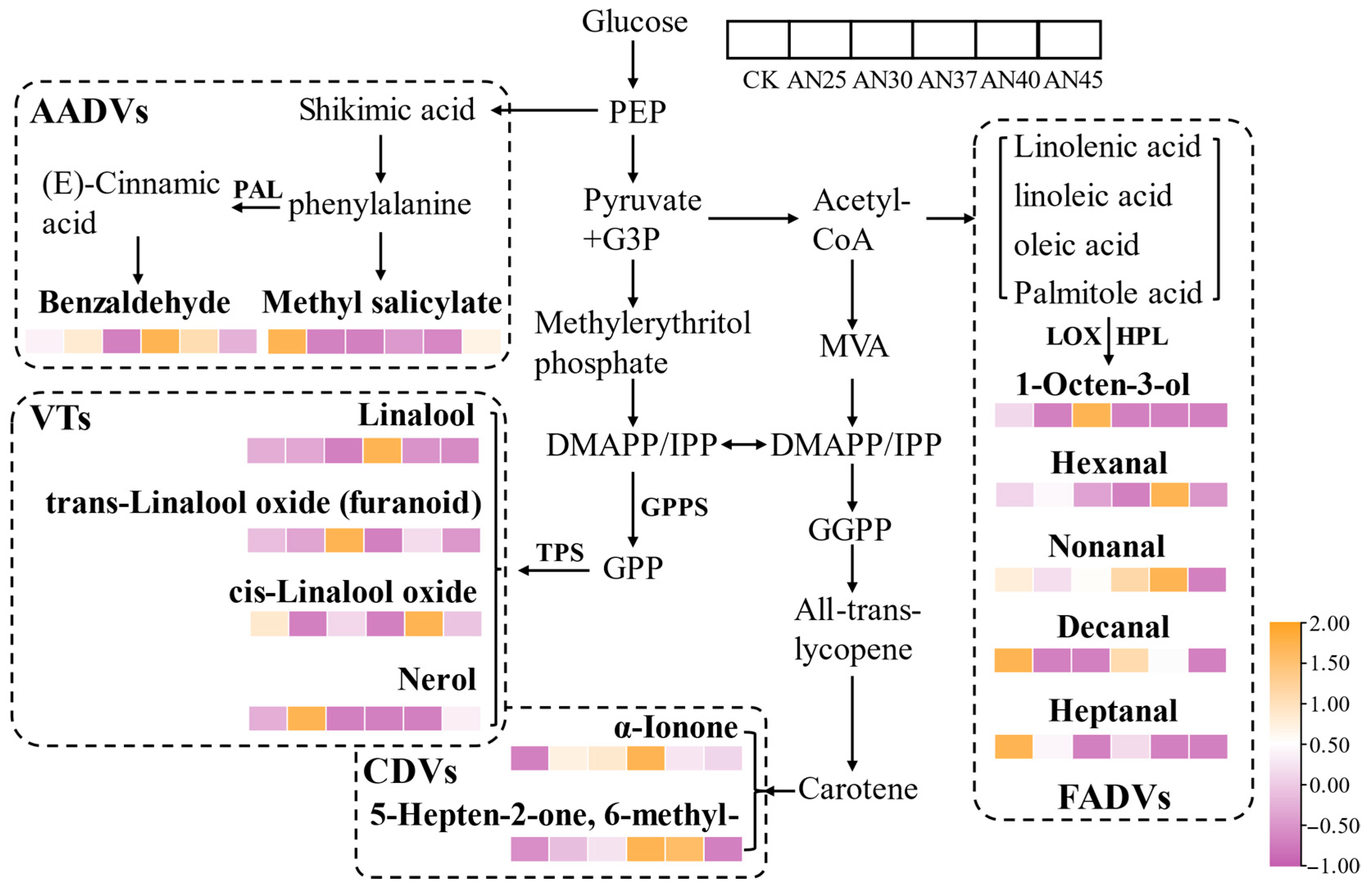

3.6. Formation Mechanism of Key Volatile Compounds

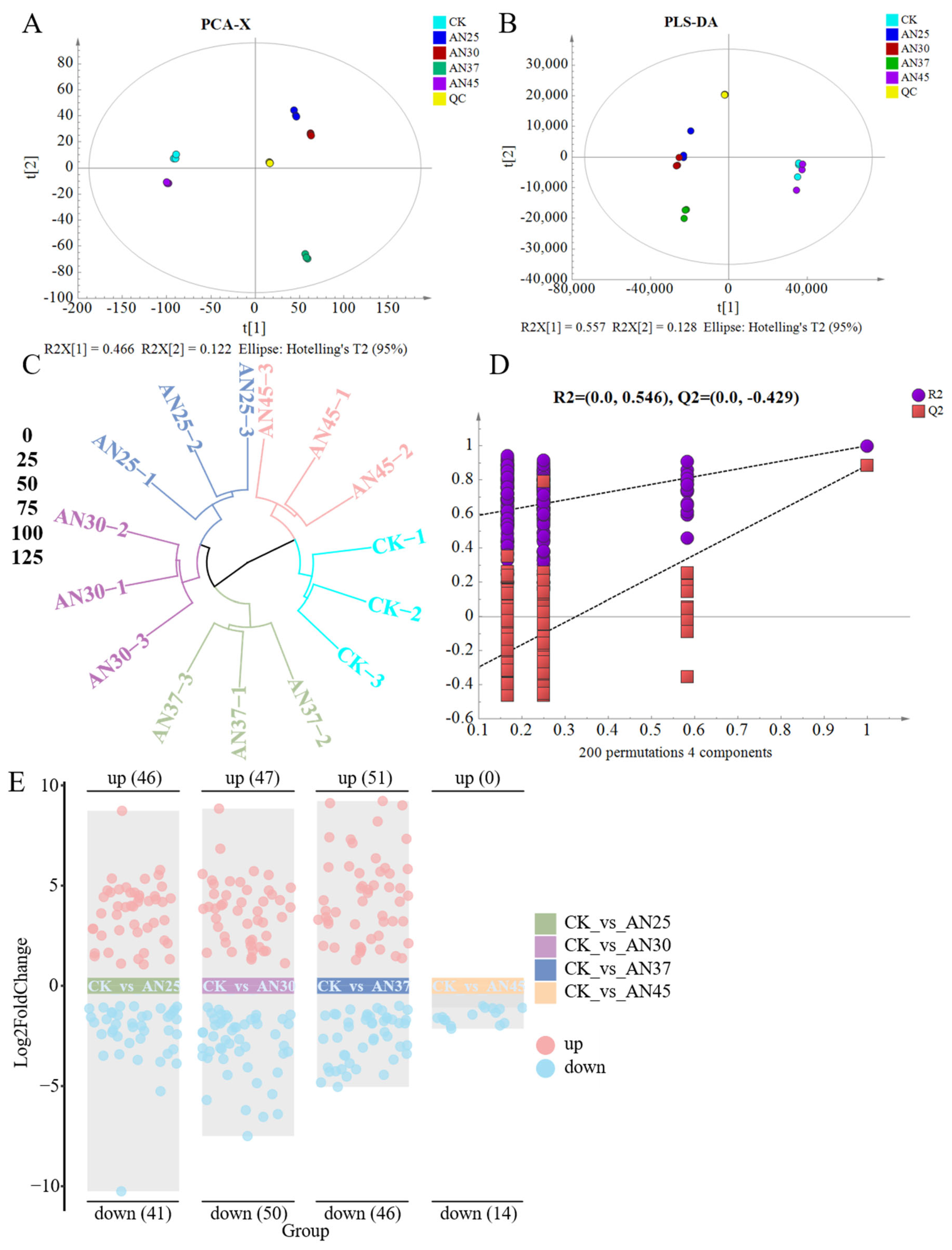

3.7. Inoculation with AN at Different Fermentation Temperatures Impacts the Composition of Non-Volatile Compounds in Dark Tea

3.7.1. Flavonoids

3.7.2. Amino Acid and Its Metabolites

3.7.3. Phenolic Acids and Organic Acid and Its Derivatives

3.7.4. Nucleotide and Its Metabolites

3.7.5. Carbohydrates and Its Metabolites

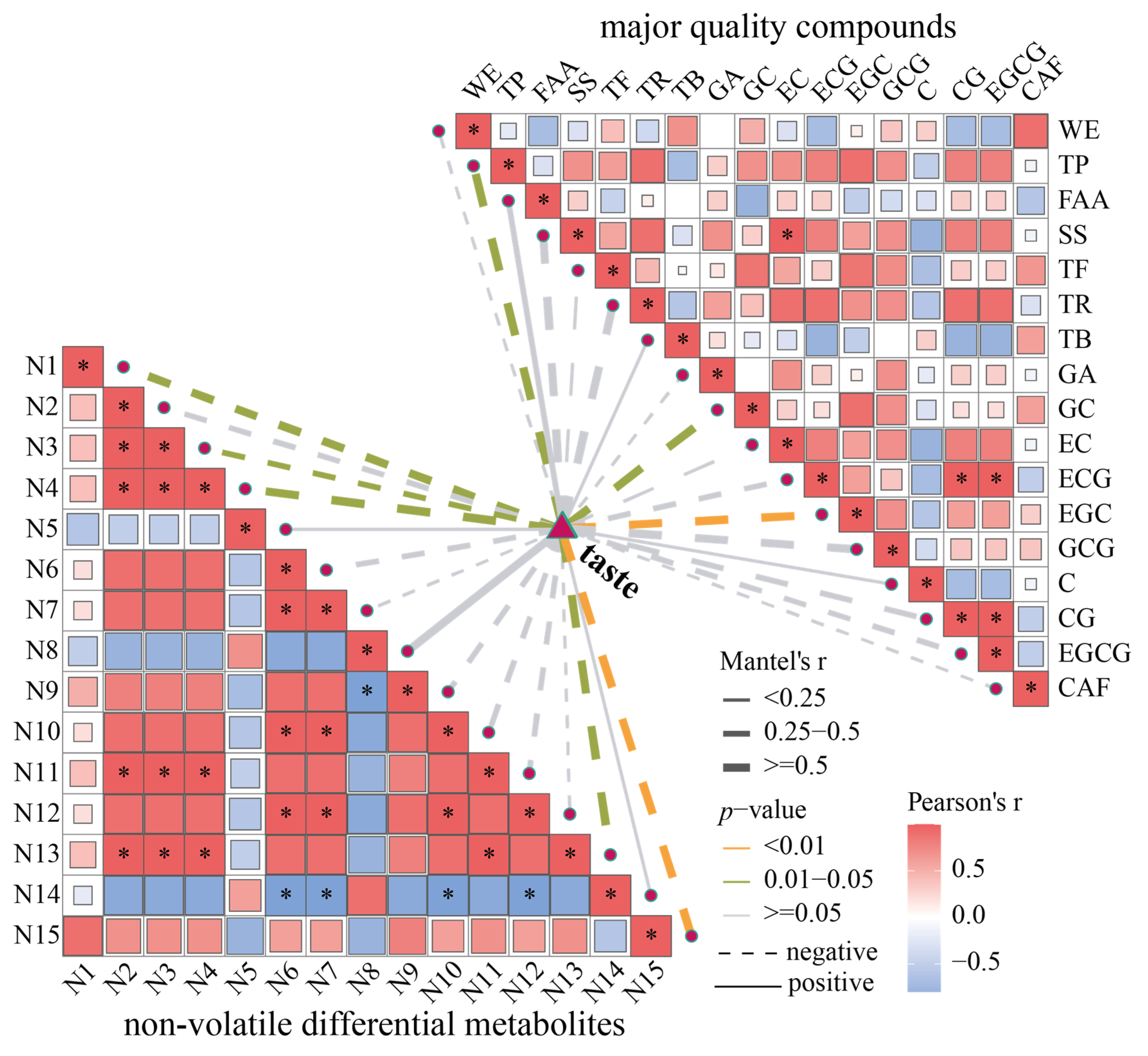

3.8. Correlation Between Key Volatile and Non-Volatile Compounds and Flavor Factors

3.9. Analysis of Industrial Scalability and Sustainability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weng, Y.; Chen, L.; Kun, J.; He, S.; Tong, H.; Chen, Y. The unique aroma of ripened Pu-erh tea, Liupao tea and Tietban tea: Associated post-fermentation condition and dominant microorganism with key aroma—Active compound. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Li, N.; Zhou, F.; Ouyang, J.; Lu, D.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, J.; et al. Microbial bioconversion of the chemical components in dark tea. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.Y.; Chen, M.F.; Hu, Y.C.; Kong, Y.S.; Ling, T.J. Microbial and chemical diversity analysis reveals greater heterogeneity of Liubao tea than ripen Pu-erh tea. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Gao, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Teng, J.; Ye, F.; Gui, A.; Xue, J.; et al. Microbial diversity and characteristic quality formation of Qingzhuan tea as revealed by metagenomic and metabolomic analysis during pile fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; Sui, M.; Jiang, G.; Xiao, J.; Ning, Y.; Ma, C.; et al. Microbial community succession in the fermentation of Qingzhuan tea at various temperatures and their correlations with the quality formation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 382, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Fan, R.; Fang, R.; Shen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, J.; Hou, R.; Sun, R.; Bao, S.; Chen, Q.; et al. Dynamics changes in metabolites and pancreatic lipase inhibitory ability of instant dark tea during liquid-state fermentation by Aspergillus niger. Food Chem. 2024, 448, 139136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 2761-2021; National Food Safety Standard—Maximum Levels of Mycotoxins in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China/National Medical Products Administration: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Yao, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Pan, X.; Zhu, W.; Huang, Y. Appropriately raising fermentation temperature beneficial to the increase of antioxidant activity and gallic acid content in Eurotium cristatum—Fermented loose tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Cao, Y.; Fang, R.; Li, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, S.; Fan, R.; Fu, J.; Zou, F.; Yue, P.; et al. Development of aroma attributes and volatile components during liquid-state fermentation of instant dark tea by Aspergillus niger. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 23776-2018; Methodology for Sensory Evaluation of Tea. State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China/Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 8305-2013; Tea—Determination of Water Extracts Content. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China/Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB/T 8313-2018; Determination of Total Polyphenols and Catechins Content in Tea. State Administration for Market Regulation of the People’s Republic of China/Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 8314-2013; Tea—Determination of Free Amino Acids Content. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China/Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Pu, Q.; Li, M.; Qu, A.; Liu, Y.; Qi, M.; Shen, T.; Sun, R.; Wu, S.; Qin, W.; Xiao, J.; et al. Dynamic evolution of volatile and non-volatile metabolic profiles in black tea during fermentation on an industrial scale. Food Chem. 2025, 485, 144582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Ma, C.; Huang, Y. GC–MS and LC-MS/MS metabolomics revealed dynamic changes of volatile and non-volatile compounds during withering process of black tea. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Y. Research progress of microorganisms during fermentation of dark tea. China Tea 2024, 46, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Bo, N.; Sha, G.; Lu, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, M. Effect of Inoculation with Debaryomyces hansenii on the Microbial Community and Quality of Pu-erh Tea during Fermentation. Food Sci. 2025, 46, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Belbahi, A.; Leguerinel, I.; Meot, J.M.; Loiseau, G.; Madani, K.; Bohuon, P. Modelling the effect of temperature, water activity and carbon dioxide on the growth of Aspergillus niger and Alternaria alternata isolated from fresh date fruit. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Pan, H.; Hu, C.; Le, M.; Long, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xie, Z.; Ling, T. Rolling forms the diversities of small molecular nonvolatile metabolite profile and consequently shapes the bacterial community structure for Keemun black tea. Food Res. Int. 2024, 181, 114094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Research on the Enzymological Characteristics of Polyphenol Oxidase from Tea and the Effect of Infrared on Its Activity and Conformation; Jiangnan University: Wuxi, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, P.; Li, P.; Chen, C.; et al. Study on the correlation between color and taste of beauty tea infusion and the pivotal contributing compounds based on UV–visible spectroscopy, taste equivalent quantification and metabolite analysis. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Effects of Different Temperatures on Fermentation Quality of Qingzhuan Tea. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, D.; Shi, Y.; Lu, M.; Ma, C.; Dong, C. Effect of withering/spreading on the physical and chemical properties of tea: A review. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Chen, M.; Song, H.; Ma, S.; Ou, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Pan, Y.; et al. A systemic review on Liubao tea: A time-honored dark tea with distinctive raw materials, process techniques, chemical profiles, and biological activities. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 5063–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Wang, L.; Xue, R.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Pu, Q.; Fang, X.; Liu, B.; Hu, X.; et al. The aroma formation from fresh tea leaves of Longjing 43 to finished Enshi Yulu tea at an industrial scale. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2025, 105, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Ding, F.; Chen, C.; Zhong, S.; Li, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yue, P.; Li, P.; et al. Comparative Metabolomic Analysis Reveals the Differences in Nonvolatile and Volatile Metabolites and Their Quality Characteristics in Beauty Tea with Different Extents of Punctured Leaves by Tea Green Leafhopper. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2023, 71, 16233–16247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; Ding, F.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Jia, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the quality formation mechanism during the processing of black tea. NPJ Sci. Food. 2025, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Pu-erh tea unique aroma: Volatile components, evaluation methods and metabolic mechanism of key odor-active compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xin, H.; Zheng, X.X.; Xu, Y.Q.; Lai, X.M.; Teng, C.Q.; Wu, W.L.; Huang, J.N.; Liu, Z.H. Characterization of key aroma compounds and core functional microorganisms in different aroma types of Liupao tea. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Shao, C.; Yan, H.; Lin, Z.; Lv, H. Insight into the volatile profiles of four types of dark teas obtained from the same dark raw tea material. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Zheng, X.; Li, S. Tea aroma formation. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2015, 4, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y.; Tu, Z.; Lin, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, P. Oxygen-enriched fermentation improves the taste of black tea by reducing the bitter and astringent metabolites. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, N.; Tu, P.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L. Change in Tea Polyphenol and Purine Alkaloid Composition during Solid-State Fungal Fermentation of Postfermented Tea. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2012, 60, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fang, T.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y. Widely targeted metabolomics using UPLC-QTRAP-MS/MS reveals chemical changes during the processing of black tea from the cultivar Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze cv. Huangjinya. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, O.P.; Qin, W.M.; Dhanjoon, J.; Ye, J.; Singh, A. Physiology and Biotechnology of Aspergillus. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Cui, Y.; Granato, D.; Wen, M.; Han, Z.; Zhang, L. Free, soluble conjugated and insoluble bonded phenolic acids in Keemun black tea: From UPLC-QQQ-MS/MS method development to chemical shifts monitoring during processing. Food Res. Int. 2022, 155, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Qiu, X.; Ye, N.; Qian, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, P.; Chen, M. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-orbitrap ultra high resolution mass spectrometry to quantitate nucleobases, nucleosides, and nucleotides during white tea withering process. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L.; Xia, N.; Teng, J.; Zhu, P. Exploring the microbial community, physicochemical properties, metabolic characteristics, and pathways during tank fermentation of Liupao tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 204, 116449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y. Characterization and evaluation of umami taste: A review. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Yao, F.; Sun, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Systemic characteristics of biomarkers and differential metabolites of raw and ripened pu-erh teas by chemical methods combined with a UPLC-QQQ-MS-based metabolomic approach. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 136, 110316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Feng, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, L.; Ye, L.; Fu, J.; Lv, H.; Mu, D.; Dong, C.; et al. Insights into major pigment accumulation and (non) enzymatic degradations and conjugations to characterized flavors during intelligent black tea processing. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wang, K.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Characterization of the key aroma compounds and microorganisms during the manufacturing process of Fu brick tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 127, 109355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, J.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H.; Ye, N.; Wang, F.; Jin, S. Analysis of pivotal compounds in NanLuShuiXian tea infusion that connect its color and taste. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Cui, L.; Geng, T.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Z. Targeted and nontargeted metabolomics analysis for determining the effect of different aging time on the metabolites and taste quality of green tea beverage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 187, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Infusion Color (Score) | Aroma (Score) | Taste (Score) | Residue Leaves (Score) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | green, yellow (84.00 ± 1.00 ab) | mellow (74.67 ± 1.53 c) | astringency (75.33 ± 0.58 d) | green, brown, and hard (70.00 ± 0.00 d) | 75.87 ± 0.88 d |

| AN25 | dark orange (81.33 ± 0.58 cd) | mold, mushroom (84.67 ± 1.15 a) | fungal taste (84.00 ± 0.00 b) | bluish brown, soft (84.00 ± 1.00 b) | 83.83 ± 0.58 a |

| AN30 | orange, brown (80.00 ± 0.00 d) | heavy, fungal smell (83.33 ± 0.58 a) | fungal taste, mellow (81.33 ± 1.15 c) | bluish brown, soft (82.00 ± 0.00 c) | 81.9 ± 0.59 b |

| AN37 | orange (83.00 ± 1.00 bc) | fungal smell (80.00 ± 0.00 b) | fungal taste (88.33 ± 0.58 a) | liver dark reddish, softer (87.33 ± 0.58 a) | 84.52 ± 0.43 a |

| AN40 | orange red (86.00 ± 0.00 a) | low, fungal smell (65.00 ± 1.00 d) | fungal taste (70.67 ± 1.15 e) | liver dark (85.33 ± 0.58 b) | 72.45 ± 0.84 e |

| AN45 | orange red (74.00 ± 1.00 e) | mellow (80.00 ± 0.00 b) | mellow astringency (80.00 ± 0.00 c) | soft, light brown, red (66.67 ± 1.15 e) | 77.77 ± 0.26 c |

| Components | CK | AN25 | AN30 | AN37 | AN40 | AN45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WE (mg/g) | 439.76 ± 4.90 a | 411.10 ± 3.99 b | 444.18 ± 1.48 a | 413.63 ± 9.55 b | 415.40 ± 4.44 b | 410.54 ± 2.35 b |

| TP (mg/g) | 136.01 ± 0.56 a | 113.24 ± 0.32 c | 103.49 ± 0.33 d | 100.80 ± 1.13 e | 92.96 ± 0.89 f | 128.73 ± 0.41 b |

| FAA (mg/g) | 7.35 ± 0.04 d | 7.56 ± 0.24 cd | 7.13 ± 0.02 e | 9.59 ± 0.04 b | 10.64 ± 0.04 a | 7.68 ± 0.07 c |

| SS (mg/g) | 82.11 ± 0.75 a | 58.15 ± 0.58 d | 50.91 ± 0.82 e | 58.41 ± 0.60 d | 64.19 ± 1.16 c | 67.35 ± 0.20 b |

| TF (mg/g) | 0.59 ± 0.05 a | 0.36 ± 0.06 b | 0.54 ± 0.04 a | 0.53 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.04 b | 0.54 ± 0.08 a |

| TR (mg/g) | 43.92 ± 0.33 a | 20.94 ± 1.33 c | 8.95 ± 0.55 f | 13.47 ± 0.58 d | 11.55 ± 0.40 e | 34.91 ± 0.49 b |

| TB (mg/g) | 43.09 ± 0.84 d | 42.41 ± 1.01 de | 48.69 ± 0.34 b | 50.44 ± 0.65 a | 46.66 ± 0.28 c | 40.81 ± 0.29 e |

| GA (mg/g) | 2.89 ± 0.03 a | 2.75 ± 0.06 a | 1.33 ± 0.10 c | 2.79 ± 0.22 a | 2.20 ± 0.12 b | 1.89 ± 0.06 b |

| GC (mg/g) | 8.18 ± 0.08 a | 6.54 ± 0.15 b | 8.11 ± 0.58 a | 5.41 ± 0.49 c | 5.07 ± 0.33 c | 7.63 ± 0.27 a |

| EC (mg/g) | 5.77 ± 0.01 a | 4.08 ± 0.10 b | 2.37 ± 0.20 c | 4.32 ± 0.35 b | 1.79 ± 0.13 d | 5.72 ± 0.22 a |

| ECG (mg/g) | 9.37 ± 0.07 a | 1.62 ± 0.03 b | 0.84 ± 0.06 c | 1.51 ± 0.12 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 c | 9.71 ± 0.38 a |

| EGC (mg/g) | 18.74 ± 0.45 a | 15.10 ± 0.34 b | 15.90 ± 0.78 b | 12.41 ± 1.13 c | 10.34 ± 0.66 d | 16.01 ± 0.73 b |

| GCG (mg/g) | 5.86 ± 0.10 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b |

| C (mg/g) | 3.05 ± 0.05 cd | 7.51 ± 0.17 a | 6.16 ± 0.49 b | 3.23 ± 0.22 c | 3.17 ± 0.22 c | 2.44 ± 0.07 d |

| CG (mg/g) | 2.77 ± 0.05 a | 2.08 ± 0.05 b | 0.48 ± 0.03 d | 1.35 ± 0.10 c | 0.48 ± 0.02 d | 2.88 ± 0.08 a |

| EGCG (mg/g) | 28.55 ± 0.27 a | 2.93 ± 0.07 b | 1.93 ± 0.16 c | 2.17 ± 0.08 bc | 1.87 ± 0.13 c | 29.23 ± 0.65 a |

| CAF (mg/g) | 13.24 ± 0.16 b | 9.04 ± 0.10 c | 18.64 ± 0.95 a | 12.98 ± 0.46 b | 19.69 ± 0.91 a | 12.72 ± 0.28 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niaz, R.; Li, M.; Pu, Q.; Qu, A.; Shen, T.; Qi, M.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y. Influences of Fermentation Temperature on Volatile and Non-Volatile Compound Formation in Dark Tea: Mechanistic Insights Using Aspergillus niger as a Model Organism. Foods 2026, 15, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030441

Niaz R, Li M, Pu Q, Qu A, Shen T, Qi M, Wang C, Chen L, Wu S, Huang Y. Influences of Fermentation Temperature on Volatile and Non-Volatile Compound Formation in Dark Tea: Mechanistic Insights Using Aspergillus niger as a Model Organism. Foods. 2026; 15(3):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030441

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiaz, Rida, Mingjin Li, Qian Pu, Anlan Qu, Tianci Shen, Minghui Qi, Chengtao Wang, Lixia Chen, Shuang Wu, and Youyi Huang. 2026. "Influences of Fermentation Temperature on Volatile and Non-Volatile Compound Formation in Dark Tea: Mechanistic Insights Using Aspergillus niger as a Model Organism" Foods 15, no. 3: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030441

APA StyleNiaz, R., Li, M., Pu, Q., Qu, A., Shen, T., Qi, M., Wang, C., Chen, L., Wu, S., & Huang, Y. (2026). Influences of Fermentation Temperature on Volatile and Non-Volatile Compound Formation in Dark Tea: Mechanistic Insights Using Aspergillus niger as a Model Organism. Foods, 15(3), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030441