Microbiological Assessment and Production of Ochratoxin A by Fungi Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Physical Chemical Analyses

2.3. Microbiological Analyses

Isolation and Enumeration

2.4. Ochratoxin A (OTA) Quantification in Socol

2.5. In Vitro Evaluation of the OTA Production Potential by Fungi Isolated from Socol

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Chemical and Microbiological Analyses

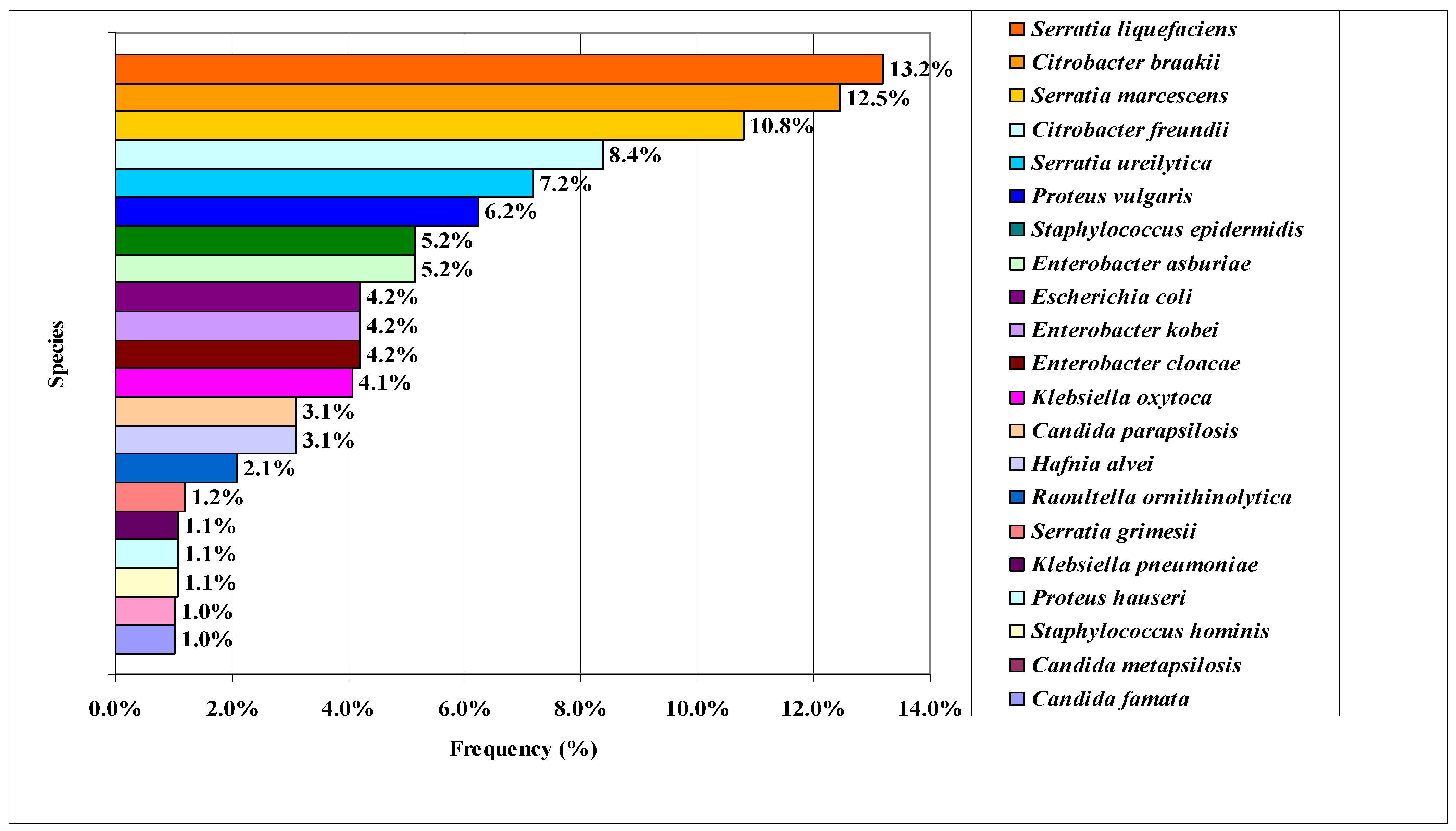

3.2. Proteomic Identification of Microorganisms Isolated from Socol

3.3. Enumeration and Identification of Fungi from Socol

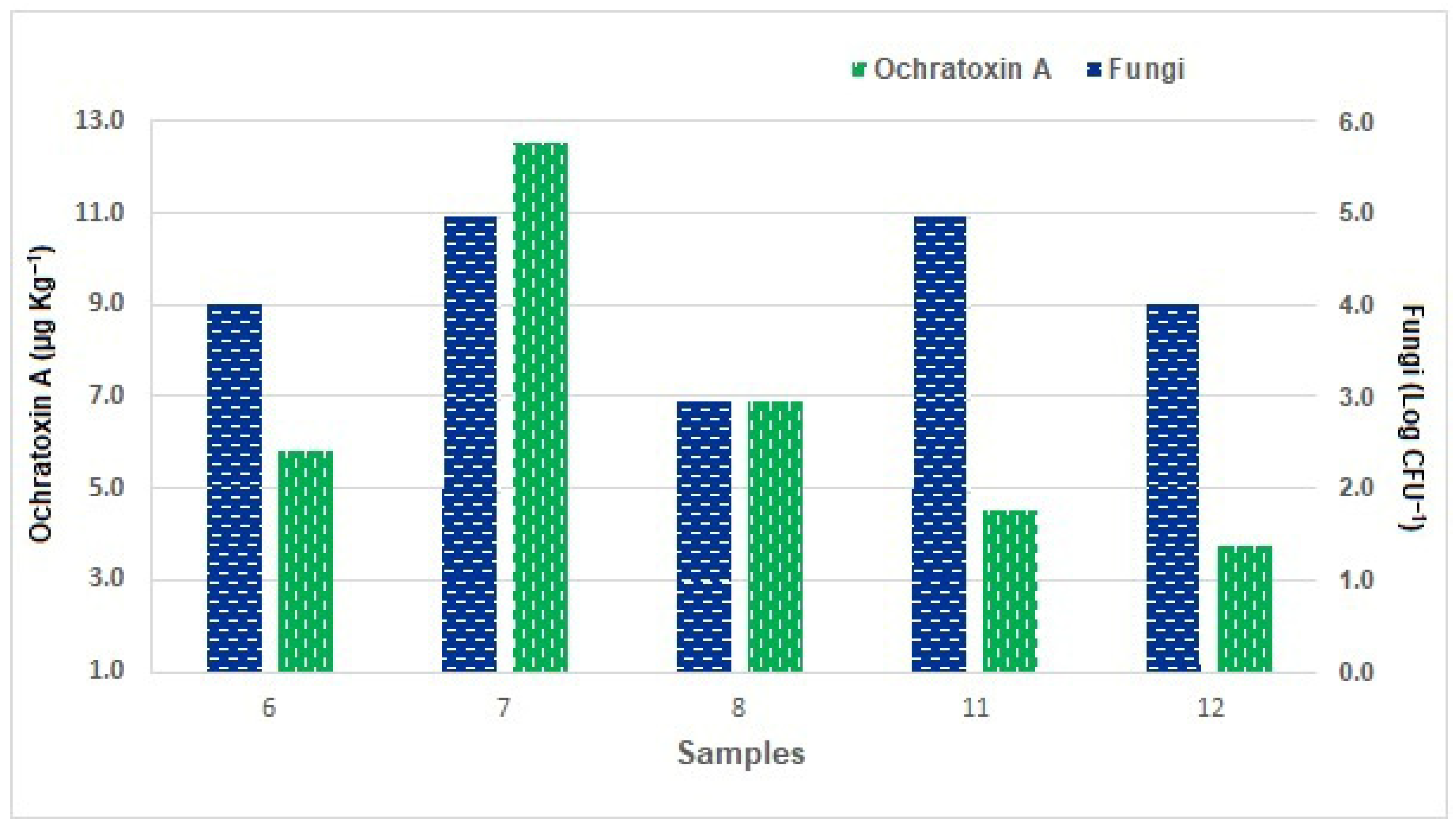

3.4. Ochratoxin A (OTA) in Socol

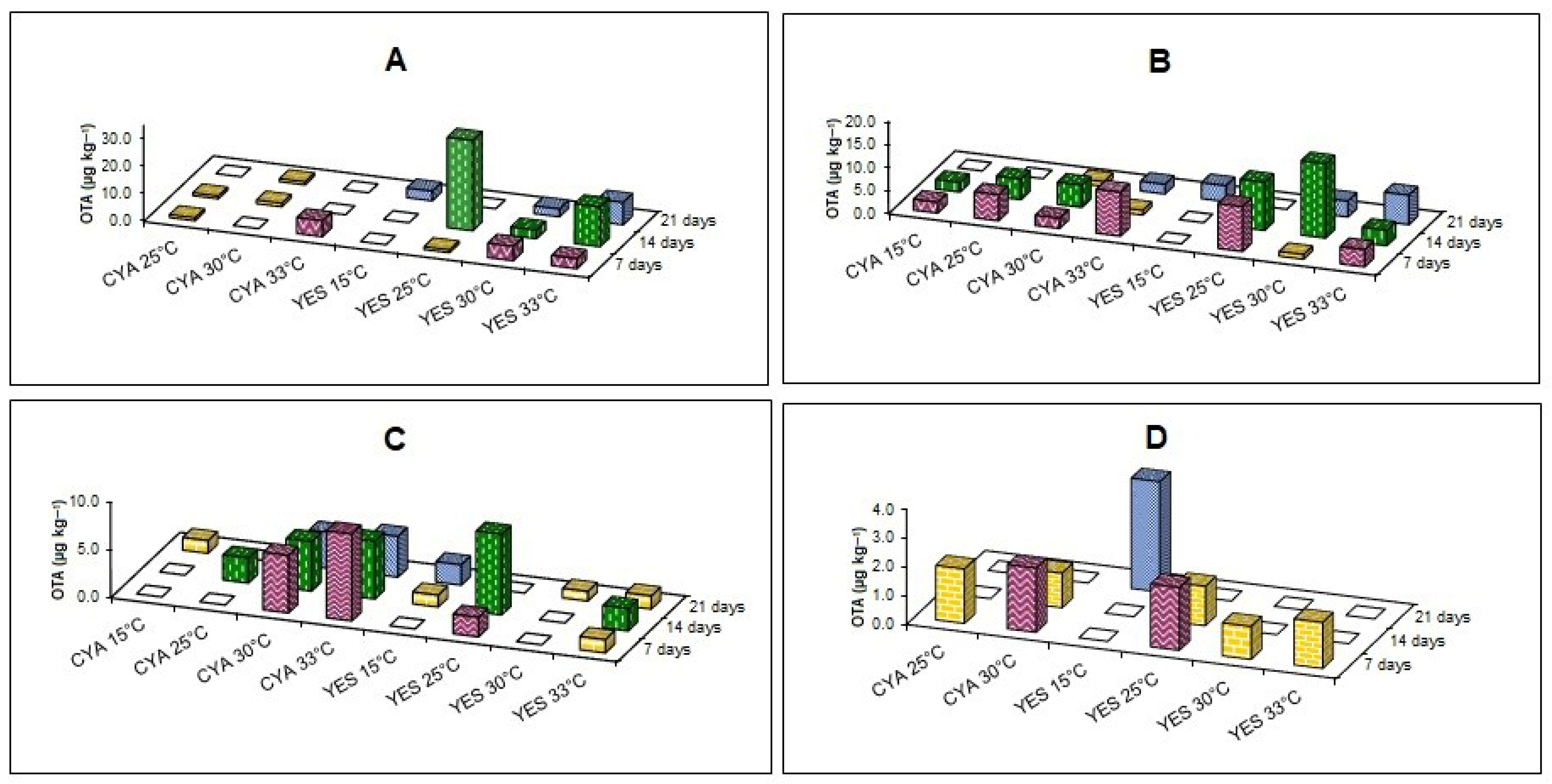

3.5. Production of Ochratoxin A (OTA) by Filamentous Fungi Isolated from Socol

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossi, F.; Tucci, P.; Del Matto, I.; Marino, L.; Amadoro, C.; Colavita, G. Autochthonous Cultures to Improve Safety and Standardize Quality of Traditional Dry Fermented Meats. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1306–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INPI (Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial). Revista da Propriedade Industrial; Indicações Geográficas; 2475, s. IV.; INPI: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, T.T.M.; Hosken, B.O.; Venturim, B.C.; Lopes, I.L.; Martin, J.G.P. Traditional Brazilian fermented foods: Cultural and technological aspects. J. Ethn. Foods 2022, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Scholliers, P.; Amillien, V. Elements of innovation and tradition in meat fermentation: Conflicts and synergies. Food. Sci. Tech. 2015, 31, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, M.V. Yeasts and molds in fermented food production: An ancient bioprocess. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 25, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Khalifa, I.; Mesak, M.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Farag, M.A. A comprehensive review of the role of microorganisms on texture change, flavor and biogenic amines formation in fermented meat with their action mechanisms and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 3538–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visagie, C.M.; Varga, J.; Houbraken, J.; Meijer, M.; Kocsubé, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Fotedar, R.; Seifert, K.A.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Ochratoxin production and taxonomy of the yellow aspergilli (Aspergillus section Circumdati). Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.P.; Teixeira, S.C.; Vieira, L.H.S.; Pereira, L.L. Caracterização da Associação de Produtores de Socol como Arranjo Produtivo Local: Uma contribuição para a valorização do agronegócio artesanal. Entrepreneurship 2019, 3, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association Of Official Analytical Chemists. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 19th, ed; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM); U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2001. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bacteriological-analytical-manual-bam (accessed on 21 January 2026).

- ISO 6579-1:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Assis, G.B.N.; Pereira, F.L.; Zegarra, A.U.; Taveres, G.C.; Leal, C.A.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Use of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for the fast identification of Gram-Positive fish pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Kanaujia, P.K.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: An emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.A.; Hoekstra, E.S.; Frisvad, J.C. Introduction to Food- and Airborne Fungi, 7th ed.; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Klich, M.A. Identification of Common Aspergillus Species; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.I. A Laboratory Guide to Common Penicillium Species; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Division of Food Research: Canberra, Australia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Biscoto, G.L.; Salvato, L.A.; Alvarenga, E.R.; Dias, R.R.S.; Pinheiro, G.R.G.; Rodrigues, M.P.; Pinto, P.N.; Freitas, R.P.; Keller, K.M. Mycotoxins in Cattle Feed and Feed Ingredients in Brazil: A Five-Year Survey. Toxins 2022, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Frank, J.M.; Houbraken, J. New ochratoxin producing species of Aspergillus section Circumdati. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Geisen, R. Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Detection of Potential Aflatoxin and Sterigmatocystin Producing Fungi. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudamore, K.A.; MacDonald, S.J. A collaborative study of an HPLC method for determination of ochratoxin A in wheat using immunoaflinity column clean-up. Food Addit. Contam. 1998, 15, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; González-Mohino, A.; Rufo, M.; Paniagua, J.M.; Antequera, T.; Perez-Palacios, T. Dry-cured loin characterization by ultrasound physicochemical and sensory parameters. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 2603–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Eom, J.U.; Yang, H.S. Comparing Physicochemical Properties, Fatty Acid Profiles, Amino Acid Composition, and Volatile Compounds in Dry-Cured Loin: The Impact of Different Levels of Proteolysis and Lipid Oxidation. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, A.; Babu, L.; Ramlal, S.; Sripathy, M.H.; Batra, H. Selective and concurrent detection of viable Salmonella spp., E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli O157:H7, and Shigella spp., in low moisture food products by PMA-mPCR assay with internal amplification control. LWT 2017, 86, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscola, V.; Todorov, S.D.; Capuano, V.S.C.; Abriouel, H.; Gálvez, A.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Isolation and characterization of a nisin-like bacteriocin produced by a Lactococcus lactis strain isolated from charqui, a Brazilian fermented, salted and dried meat product. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B.; Yao, D.; Zeng, C.; Cao, J.; Li, L.; Huang, R. Characterization the microbial diversity and metabolites of four varieties of Dry-Cured ham in western Yunnan of China. Food Chem. 2024, 22, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi, A.; Pisacane, V.; Miragoli, F.; Polka, J.; Falaskoni, I.; Morelli, L.; Puglisi, E. High-throughput assessment of bacterial ecology in hog, cow and ovine casings used in sausages production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 212, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundog, D.A.; Ozkaya, Y.; Gungor, C. Pathogenic potential of meat-borne coagulase negative staphylococci strains from slaughterhouse to fork. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F.; Indio, V.; Giacometti, F.; Mekkonnen, Y.T.; De Cesare, A.; Prandini, L.; Marrone, R.; Seguino, A.; Di Paolo, M.; Vuoso, V.; et al. Microbiological safety of dry-aged meat: A critical review of data gaps and research needs to define process hygiene and safety criteria. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Luque, O.M.; Valero, A.; Tomasello, F.; Cabo, M.L.; Rodríguez-López, P.; Possas, A. Exploring microbial diversity during the artisanal Salchichón production: Food safety in the consumer spotlight. LWT 2024, 191, 115550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xia, Q.; Du, L.; He, J.; Sun, Y.; Dang, Y.; Geng, F.; Pan, D.; Cao, J.; Zhou, G. Recent developments in off-odor formation mechanism and the potential regulation by starter cultures in dry-cured ham. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8781–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losantos, A.; Sanabria, C.; Cornejo, I.; Carrascosa, A.V. Characterization of Enterobacteriaceae strains isolated from spoiled dry-cured hams. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, F.; Valero, A.; Possas, A.; Lucchi, A.; Crippa, C.; Gambi, L.; Manfreda, G.; De Cesare, A. Variability in Physicochemical Parameters and Its Impact on Microbiological Quality and Occurrence of Foodborne Pathogens in Artisanal Italian Organic Salami. Foods 2023, 12, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, M.M.F.; Maran, B.M.; Maran, E.M.; Miotto-Lindner, M.; Verruck, S. Assessment of microbial ecology in artisanal salami during maturation via metataxonomic analysis. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, e00147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Mi, R.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Q.; Xiong, S.; Qi, B.; Wang, S. Evaluation and selection of yeasts as potential aroma enhancers for the production of dry-cured ham. FSHW 2023, 12, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, L.M.; Padilla, B.; Carmela, B.V.; Vignolo, G.; De Las Rivas, B. Diversity and enzymatic profile of yeasts isolated from traditional llama meat sausages from north-western Andean region of Argentina. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoncini, N.; Rotelli, D.; Virgili, R.; Quintavalla, S. Dynamics and characterization of yeasts during ripening of typical Italian dry-cured ham. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Tang, N.; Huang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, B.C.; Li, P.J. Isolation, identification and tolerance characteristics of microorganisms from Weining Ham. Meat Res. 2019, 33, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Béjar, B.; Árevalo-Villena, M.; Briones, A. Characterization of yeast population from unstudied natural sources in La Mancha region. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, B.M.; Oh, M.H. Potential Correlation between Microbial Diversity and Volatile Flavor Compounds in Different Types of Korean Dry-Fermented Sausages. Foods. 2022, 11, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, J. Debaryomyces hansenii Strains from Traditional Chinese Dry-Cured Ham as Good Aroma Enhancers in Fermented Sausage. Fermentation 2024, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, Y.S.; Rosario, D.K.A.; Bernardo, Y.A.A.; Vieira, C.P.; Moreira, R.V.P.; Bernardes, P.C.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Unravelling the relation between natural microbiota and biogenic amines in Brazilian dry-cured loin: A chemometric approach. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, C.; Bassi, D.; López, C.; Pisacane, V.; Otero, M.C.; Puglisi, E.; Rebecchi, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Vignolo, G. Microbial ecology involved in the ripening of naturally fermented llama meat sausages. A focus on lactobacilli diversity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 236, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipotnik, Z.; Rodríguez, A.; Rodrigues, P. Aspergillus westerdijkiae as a major ochratoxin A risk in dry-cured ham based-media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, F.C.; Valente, G.L.C.; Santos, V.P.F.; Soares, C.F.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Cançado, S.d.V.; Figueiredo, T.C.; Souza, M.R. In Vitro Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol). Microorganisms. 2025, 13, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, B.; Humza, M.; Geng, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Gao, S.; Xing, F.; Liu, Y. A novel strain Lactobacillus brevis 8-2B inhibiting Aspergillus carbonarius growth and ochratoxin a production. LWT 2021, 136, 110308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia Ministero della Sanità. Circolare 09.06.1999. In Gazzetta Ufficiale Repubblica Italiana; Sanità, M.D., Ed.; Circolare. (v. 135); Ministero della Sanità: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1370 of 5 August 2022 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of ochratoxin A in certain foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L 206/11, 11–14.

- Iacumim, L.; Chiesa, L.; Boscolo, D.; Manzano, M.; Cantoni, C.; Orlic, S.; Comi, G. Moulds and ochratoxin A on surfaces of artisanal and industrial dry sausages. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, T.; Gualla, A.; Morlacchini, M.; Pietri, A. Direct and indirect contamination with ochratoxin A of ripened pork products. Food Cont. 2013, 34, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleadin, J.; Staver, M.M.; Vahčić, N.; Kovačević, D.; Milone, S.A.; Saftić, L.; Scortichini, G. Survey of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A occurrence in traditional meat products coming from Croatian households and markets. Food Control. 2015, 52, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Serna, P.; García-Díaz, M.; González-Jaén, M.T.; Vázquez, C.; Patiño, B. Description of an orthologous cluster of ochratoxin A biosynthetic genes in Aspergillus and Penicillium species. A comparative analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 268, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA CONTAM Panel (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain). Scientific opinion on the risk assessment of ochratoxin A in food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoev, S.D. Balkan Endemic Nephropathy e Still continuing enigma, risk assessment and underestimated hazard of joint mycotoxin exposure of animals or humans. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2017, 261, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncero, E.; Andrade, M.J.; Álvarez, M.; Cebrián, E.; Rodríguez, M. Debaryomyces hansenii reduces ochratoxin A production by Penicillium nordicum on dry-cured ham agar through volatile compounds. LWT 2024, 213, 117030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analyses | Means | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 42.63 | 4.34 | 33.79 | 48.06 |

| Lipid content | 11.79 | 7.20 | 3.52 | 30.20 |

| Protein | 44.52 | 5.56 | 31.3 | 51.19 |

| Analyses | Means | S.D. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus spp. | 6.7 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 7.7 |

| Total coliforms | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 4.2 |

| Yeast and Molds | 4.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 7.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chow, F.C.; Valente, G.L.C.; Santos, V.P.F.; Rodrigues Wenzel, M.; Keller, K.M.; Soares, C.F.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Souza, M.R.; Cançado, S.d.V.; Figueiredo, T.C. Microbiological Assessment and Production of Ochratoxin A by Fungi Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol). Foods 2026, 15, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030433

Chow FC, Valente GLC, Santos VPF, Rodrigues Wenzel M, Keller KM, Soares CF, Figueiredo HCP, Souza MR, Cançado SdV, Figueiredo TC. Microbiological Assessment and Production of Ochratoxin A by Fungi Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol). Foods. 2026; 15(3):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030433

Chicago/Turabian StyleChow, Felipe Coser, Gustavo Lucas Costa Valente, Viviana Patrícia Fraga Santos, Mariana Rodrigues Wenzel, Kelly Moura Keller, Carla Ferreira Soares, Henrique César Pereira Figueiredo, Marcelo Resende Souza, Silvana de Vasconcelos Cançado, and Tadeu Chaves Figueiredo. 2026. "Microbiological Assessment and Production of Ochratoxin A by Fungi Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol)" Foods 15, no. 3: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030433

APA StyleChow, F. C., Valente, G. L. C., Santos, V. P. F., Rodrigues Wenzel, M., Keller, K. M., Soares, C. F., Figueiredo, H. C. P., Souza, M. R., Cançado, S. d. V., & Figueiredo, T. C. (2026). Microbiological Assessment and Production of Ochratoxin A by Fungi Isolated from Brazilian Dry-Cured Loin (Socol). Foods, 15(3), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030433