Knowledge of Dietary Supplements and Attitudes Towards Complementary Medicine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Questionnaires

2.3.1. Assessment of Knowledge About Dietary Supplements

2.3.2. Assessment of Attitude Towards CAM

2.4. Hypotheses of the Study

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Knowledge About Dietary Supplements

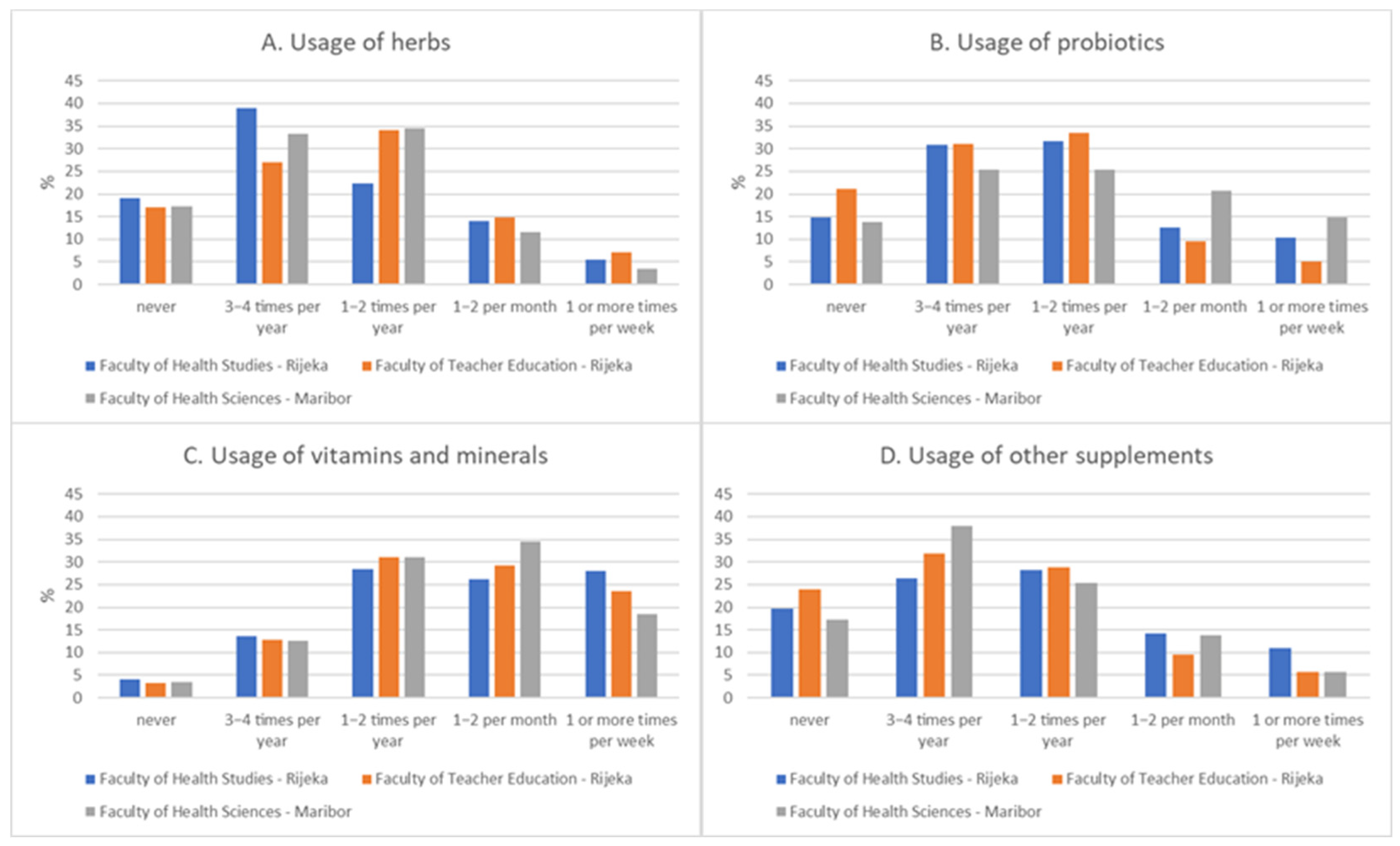

3.3. Usage of Herbs, Vitamins and Minerals, Probiotics, and Other Supplements

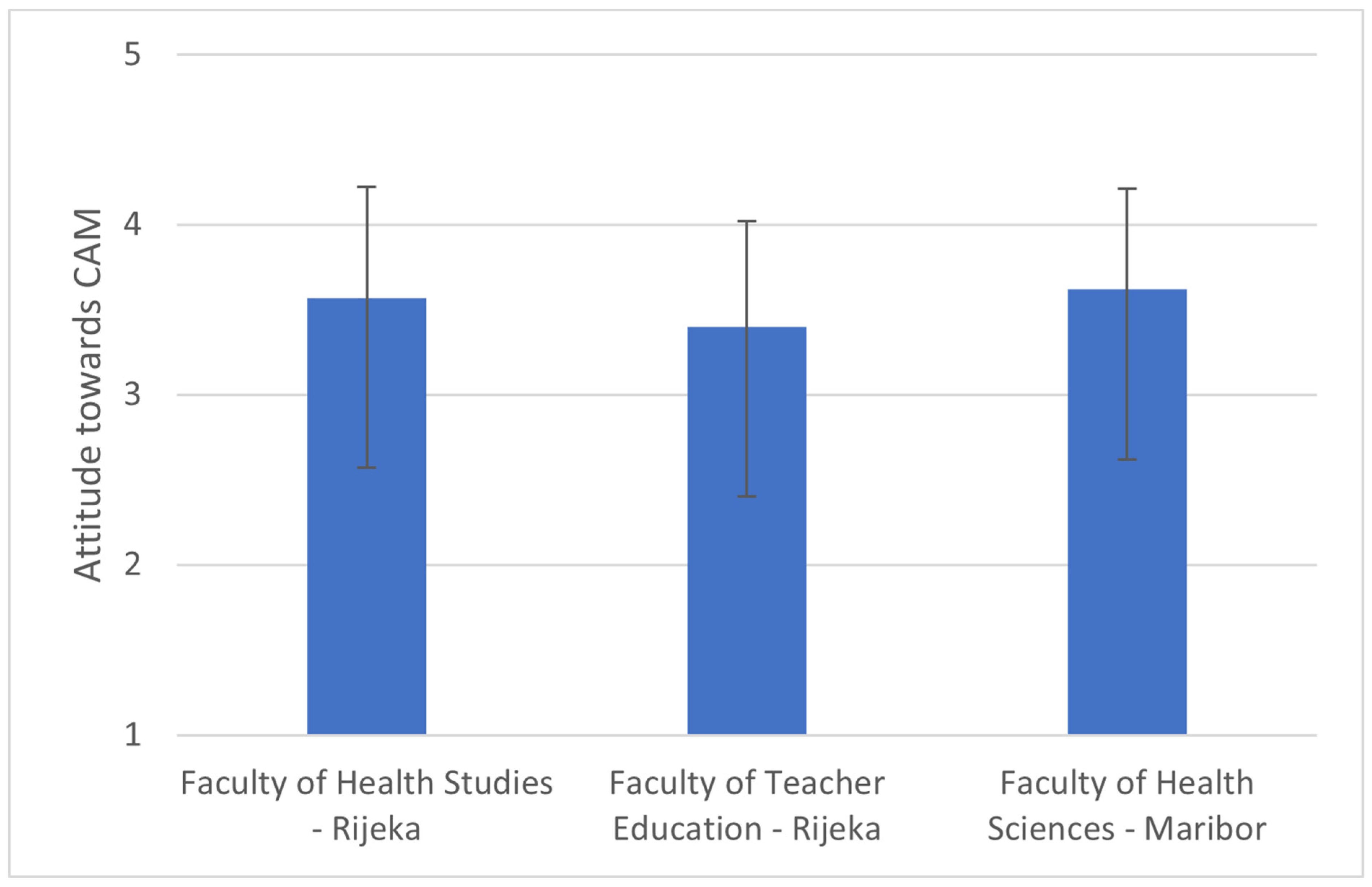

3.4. Attitude Towards CAM

3.5. Correlations of Test Results, Usage of Supplements, and Attitude Towards CAM

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge of Dietary Supplements

4.2. Usage Patterns of Dietary Supplements

4.3. Attitudes Toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine

4.4. Cross-Study Integration and Implications

4.5. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DS | dietary supplements |

| CAM | complementary and alternative medicine |

References

- Lam, M.; Khoshkhat, P.; Chamani, M.; Shahsavari, S.; Dorkoosh, F.A.; Rajabi, A.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Nokhodchi, A. In-depth multidisciplinary review of the usage, manufacturing, regulations & market of dietary supplements. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, P.M.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; El-Sohemy, A.; Floyd, E.; Goldenberg, J.Z.; Shunney, A.G.; Holscher, H.D.; Nkrumah-Elie, Y.; Rai, D.; et al. The Evolution of Science and Regulation of Dietary Supplements: Past, Present, and Future. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Saklani, S.; Kumar, P.; Kim, B.; Coutinho, H.D.M. Nutraceuticals: Pharmacologically Active Potent Dietary Supplements. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2051017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002. Off J. Eur. Communities 2002, 51–57. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2002:183:0051:0057:EN:PDF (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Siddiqui, R.A.; Moghadasian, M.H. Nutraceuticals and Nutrition Supplements: Challenges and Opportunities. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.E. Dietary supplements—For whom? The current state of knowledge about the health effects of selected supplement use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministarstvo Zdravlja. Pravilnik o Dodacima Prehrani, NN 126/2013-2740. 2013. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2013_10_126_2740.html (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Nutrient Recommendations and Databases. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/nutrientrecommendations.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Stone, M.S.; Martyn, L.; Weaver, C.M. Potassium Intake, Bioavailability, Hypertension, and Glucose Control. Nutrients 2016, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, I.; Maywald, M.; Rink, L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gröber, U.; Schmidt, J.; Kisters, K. Magnesium in Prevention and Therapy. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8199–8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, J.J.; Steelman, R.A.; Hoedebecke, S.S.; Austin, K.G.; Farina, E.K.; Lieberman, H.R. Prevalence of Dietary Supplement Use by Athletes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasek, M.; Giebultowicz, J.; Sochacka, M.; Zawada, K.; Modzelewska, W.; Krzesniak, L.M.; Wroczynski, P. The measurement of antioxidant capacity and polyphenol content in selected food supplements. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2015, 72, 877–887. [Google Scholar]

- Kotha, R.R.; Luthria, D.L. Curcumin: Biological, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and analytical aspects. Molecules 2019, 24, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, M.; Ingmer, H. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of resveratrol. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Tan, H.-Y.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Guo, W.; Feng, Y. Supplementation of Micronutrient Selenium in Metabolic Diseases: Its Role as an Antioxidant. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 7478523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, S. Kurkumin—biološki učinci, bioraspoloživost i formulacije. Diploma Thesis, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bezak, S. Resveratrol—scientific evidence of its impact on health. World Health 2022, 5, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S.A.; Trewin, A.J.; Parker, L.; Wadley, G.D. Antioxidant supplements and endurance exercise: Current evidence and mechanistic insights. Redox Biol. 2020, 35, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, M.R.; Izadi, A.; Kaviani, M. Antioxidants and Exercise Performance: With a Focus on Vitamin E and C Supplementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnagöl, H.H.; Koşar, Ş.N.; Güzel, Y.; Aktitiz, S.; Atakan, M.M. Nutritional Considerations for Injury Prevention and Recovery in Combat Sports. Nutrients 2021, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.; Nahin, R.L.; Rogers, G.T.; Barnes, P.M.; Jacques, P.M.; Sempos, C.T.; Bailey, R. Prevalence and predictors of children’s dietary supplement use: The 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; Blatman, J.; El-Dash, N.; Franco, J.C. Consumer usage and reasons for using dietary supplements: Report of a series of surveys. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2014, 33, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Stierman, B.; Gahche, J.J.; Potischman, N. Dietary Supplement Use Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief 2021, 399, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, A.K.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Connelly, S.T.; Bellinato, F.; Gisondi, P.; et al. Main nutritional deficiencies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. S3), E93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C.M.; Alexander, D.D.; Boushey, C.J.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lappe, J.M.; LeBoff, M.S.; Liu, S.; Looker, A.C.; Wallace, T.C. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: An updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, T.S.; Pan, X.; Cheek, F.; Ing, S.W.; Jackson, R.D. A systematic review of omega-3 fatty acids and osteoporosis. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107 (Suppl. S2), S253–S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Muka, T.; Troup, J.; Hu, F.B. Folic Acid Supplementation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dietary Supplements: What You Need to Know. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/WYNTK-Consumer/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Alrowais, N.A.; Alyousefi, N.A. The prevalence extent of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use among Saudis. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2017, 25, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.L.; Richards, N.; Harrison, J.; Barnes, J. Prevalence of Use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the General Population: A Systematic Review of National Studies Published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangkiatkumjai, M.; Boardman, H.; Walker, D.-M. Potential factors that influence usage of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide: A systematic review. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-García, P.A.; Ramirez-Perez, S.; Miguel-González, J.J.; Guzmán-Silahua, S.; Castañeda-Moreno, J.A.; Komninou, S.; Rodríguez-Lara, S.Q. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Practices: A Narrative Review Elucidating the Impact on Healthcare Systems. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Sang, T.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, W.; Zhou, H. A Survey on Perceptions of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Undergraduates in China. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 9091051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.B.; Bah, A.J. Awareness, use, attitude and perceived need for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) education among undergraduate pharmacy students in Sierra Leone: A descriptive cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.E.; Cooper, K.L.; Relton, C.; Thomas, K.J. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doko, T.; Salaric, I.; Bazdaric, K. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Croatian Health Studies Students—A Single Center Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Med. Acad. 2020, 49, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaoudene, O.; Romano, A.; Bradai, Y.D.; Zebiri, F.; Ouchene, A.; Yousfi, Y.; Amrane-Abider, M.; Sahraoui-Remini, Y.; Madani, K. A Global Overview of Dietary Supplements: Regulation, Market Trends, Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Health Effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadwallader, A.B. Which Features of Dietary Supplement Industry, Product Trends, and Regulation Deserve Physicians’ Attention? AMA J. Ethics 2022, 24, 410–418. [Google Scholar]

- Karbownik, M.S.; Paul, E.; Nowicka, M.; Nowicka, Z.; Kowalczyk, R.P.; Kowalczyk, E.; Pietras, T. Knowledge about dietary supplements and trust in advertising them: Development and validation of the questionnaires and preliminary results of the association between the constructs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doko, T. Spremnost Studenata Fakulteta Zdravstvenih Studija Sveučilišta u Rijeci za Korištenje Komplementarne i Alternativne Medicine. Diploma Thesis, University of Rijeka, Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. Available online: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:184:226542 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Mansoor, K.; Mallah, E.; Abuqatouseh, L.; Darwish, D.; Abdelmalek, S.; Yasin, M.; Abu-Itham, J.; Al-Khayat, A.; Matalka, K.; Qadan, F.; et al. Awareness and attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine among pharmacy- and non-pharmacy- undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102297. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877129725000188 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Homan, E.M. Dietary Supplements and College Students: Use, Knowledge, and Perception. Kent State University. 2018. Available online: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1532083809853366 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Bayır, T.; Çam, S.; Tuna, M.F. Does knowledge and concern regarding food supplement safety affect the behavioral intention of consumers? An experimental study on the theory of reasoned action. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1305964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almech, M.; Alissa, A.; Baghdadi, R.; Abujamai, J.; Hafiz, W.; Alwafi, H.; Shaikhomer, M.; Alshanberi, A.; Alshareef, M.; Alsanosi, S. Medical Students’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Herbal Medicine in Saudi Arabia: Should Medical Schools Take Immediate Action? Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2024, 15, 1243–1253. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2147/AMEP.S497642 (accessed on 11 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Odeh, M.M.; Abu Jadayil, S.; McGrattan, A.M.; Hammad, F.J.; Al-Maseimi, O.D.; Alzoubi, K.H. Prevalence of dietary supplement use and knowledge, attitudes, practice (KAP) and associated factors in student population: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, S.; Najibi, S.M.; Niknam, B.; Daneshfard, B.; Salehi-Marzijarani, M.; Azgomi, R.N.D.; Hashempur, M.H. Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Iranian Medical Students Toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Barriers Toward Using Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Medical and Nonmedical University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Saudi Arabia. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2024, 22, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaboun, S.; Salama, L.; Salama, R.; Abdrabba, F.; Shabon, F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Final-Year Pharmacy and Medical Students in Benghazi, Libya. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 15, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoro, A.; Hanif, S.; Khuwaja, T.; Zardari, M.; Zardari, A.A.; Soomro, M.N.; Razzaque, A. Knowledge, attitude and practices related to dietary supplements in undergraduate students. Insights-J. Life Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.A.; Alqahtani, S.; Aldajani, R.; Alsharabi, B.; Alzahrani, W.; Alguthami, G.; Khawagi, W.Y.; Arida, H. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Supplement Use in Western Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stayduhar, J.M.; Covvey, J.R.; Schreiber, J.B.; Witt-Enderby, P.A. Pharmacist and Student Knowledge and Perceptions of Herbal Supplements and Natural Products. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cearley, S.M. Georgia Southern Commons The Need for Complementary Alternative Medicine Knowledge among Health-Related Majors in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2014 GERA Conference, Kennesaw, GA, USA, 17–18 October 2014; Georgia Southern University: Statesboro, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Žeželj, S.P.; Tomljanović, A.; Jovanović, G.K.; Krešić, G.; Peloza, O.C.; Dragaš-Zubalj, N.; Prokurica, I.P. Prevalence, Knowledge and Attitudes Concerning Dietary Supplements among a Student Population in Croatia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Xu, D.; Xia, H.; Pan, D.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. Investigation and Comparison of Nutritional Supplement Use, Knowledge, and Attitudes in Medical and Non-Medical Students in China. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Kobayashi, E.; Okura, T.; Sekimoto, M.; Mizuno, H.; Saito, M.; Umegaki, K. An educational intervention improved knowledge of dietary supplements in college students. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawarneh, Y.; Rajab, L.; Alzeyoudi, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Alnaqbi, N.; Alkaabi, S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward complementary alternative medicine in the UAE: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2023, 64, 102310. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876382023000860 (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, M.; Dehghan, M.; Soltanmoradi, Y.; Monfared, S.; Kose, G.; Farahmandnia, H.; Hermis, A.H.; Xu, X.; Zakeri, M.A. Attitudes and use of complementary and alternative medicine: A cross-sectional comparison between medical and non-medical students. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1529079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aramesh, K.; Etemadi, A.; Sines, L.; Fry, A.; Coe, T.; Tucker, K. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and use of complementary and integrative medicine among health-major students in Western Pennsylvania and their implications on ethics education. Int. J. Ethics Educ. 2024, 9, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Rabiepoor, S.; Forough, A.S.; Jabbari, S.; Shahabi, S. A survey of medical students’ knowledge and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine in Urmia, Iran. J. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, F.; Alward, M.; Siddiqui, M.; Al-Khouri, M. Medical Students Knowledge and Perception Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine. J. Health Edu. Res. Dev. 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys, W.J.; Cudnik, M.L.; Krinsky, D.L.; Darvesh, A.S. Evolution of a Natural Products and Nutraceuticals Course in the Pharmacy Curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015, 79, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muhammed Taher, M.I.; Ibrahim, R.H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of university’s employees about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 37, 101184. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352914823000266 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Pavelić, K.; Kraljević Pavelić, S. Personalized Medicine: Challenges and a Look Forward. In Novel Perspectives in Economics of Personalized Medicine and Healthcare Systems; Družeta, R.P., Škare, M., Kraljević Pavelić, S., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sotoudeh, G.; Kabiri, S.; Yeganeh, H.S.; Koohdani, F.; Khajehnasiri, F.; Khosravi, S. Predictors of dietary supplement usage among medical interns of Tehran university of medical sciences. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Göktaş, Z.; Kalkuz, Ş. Knowledge and Attitudes of Health Professionals toward Dietary Supplements and Herbal Foods TT—Sağlık Profesyonellerinin Besin Destekleri ve Bitkisel Besinlere Yönelik Tutum ve Bilgi Düzeyleri. Ank. Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2023, 12, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phutrakool, P.; Pongpirul, K. Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: A 15-year systematic review and data synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameade, E.P.K.; Amalba, A.; Helegbe, G.K.; Mohammed, B.S. Medical students’ knowledge and attitude towards complementary and alternative medicine—A survey in Ghana. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2016, 6, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth-LaForce, C.; Scott, C.S.; Heitkemper, M.M.; Cornman, B.J.; Lan, M.-C.; Bond, E.F.; Swanson, K.M. Complementary and Alternative Medi-cine (CAM) Attitudes and Competencies of Nursing Students and Faculty: Results of Integrating CAM Into the Nursing Curriculum. J. Prof. Nurs. 2010, 26, 293–300. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S8755722310000372 (accessed on 11 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Baydoun, M.; Levin, G.; Balneaves, L.G.; Oberoi, D.; Sidhu, A.; Carlson, L.E. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Online Learning Intervention for Oncology Healthcare Providers: A Mixed-Methods Study. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 15347354221079280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Health-Focused Study—Faculty of Health Studies, Rijeka n = 480 | Non-Health-Focused Study—Faculty of Teacher Education, Rijeka n = 242 | Health-Focused Study—Faculty of Health Sciences, Maribor n = 87 | Total n = 809 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or M (SD) | ||||

| Age (years) | 24.7 (7.8) | 22.9 (7.4) | 22.8 (3.5) | 23.9 (7.4) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 383 (47.3) | 231 (28.6) | 76 (9.4) | 690 (85.3) |

| Male | 93 (11.5) | 7 (0.9) | 11 (1.4) | 111 (13.7) |

| Did not want to declare | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Study | ||||

| Bachelor | 351 (43.4) | 219 (27.1) | 75 (9.3) | 645 (79.7) |

| Master | 129 (15.9) | 23 (2.8) | 12 (1.5) | 164 (20.3) |

| Type of study | ||||

| Part-time study | 211 (26.1) | 40 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 251 (31.0) |

| Full-time study | 269 (33.3) | 105 (13.0) | 87 (10.7) | 461 (57.0) |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0) | 97 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 97 (12.0) |

| Major (field of study) | ||||

| Nursing | 220 (27.2) | / | / | 220 (27.2) |

| Midwifery | 59 (7.3) | / | / | 59 (7.3) |

| Physiotherapy | 157 (19.4) | / | / | 157 (19.4) |

| Radiological technology | 44 (5.4) | / | / | 44 (5.4) |

| Early and Preschool Education | / | 242 (29.9) | / | 242 (29.9) |

| Faculty of Health Sciences (Nursing), Maribor | / | / | 87 (10.8) | 87 (10.8) |

| Variable | Usage Supplements | Attitude Towards CAM |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample | ||

| Test % | 0.076 | 0.12 ** |

| Usage supplements | - | 0.28 ** |

| Health-focused study (Faculty of Health Studies—Rijeka) | ||

| Test % | 0.10 * | 0.09 |

| Usage supplements | - | 0.25 ** |

| Non-health-focused study (Faculty of Teacher Education—Rijeka) | ||

| Test % | 0.05 | 0.13 * |

| Usage supplements | - | 0.28 ** |

| Health-focused study (Faculty of Health Sciences—Maribor) | ||

| Test % | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| Usage supplements | - | 0.38 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bezak, S.; Baždarić, K.; Huzjak Horvat, L.; Lončarić, D.; Brandić Mičetić, V.; Fijan, S.; Šikić Pogačar, M.; Pavelić, S.K. Knowledge of Dietary Supplements and Attitudes Towards Complementary Medicine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Foods 2026, 15, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010061

Bezak S, Baždarić K, Huzjak Horvat L, Lončarić D, Brandić Mičetić V, Fijan S, Šikić Pogačar M, Pavelić SK. Knowledge of Dietary Supplements and Attitudes Towards Complementary Medicine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Foods. 2026; 15(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezak, Sara, Ksenija Baždarić, Lea Huzjak Horvat, Darko Lončarić, Vanja Brandić Mičetić, Sabina Fijan, Maja Šikić Pogačar, and Sandra Kraljević Pavelić. 2026. "Knowledge of Dietary Supplements and Attitudes Towards Complementary Medicine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study" Foods 15, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010061

APA StyleBezak, S., Baždarić, K., Huzjak Horvat, L., Lončarić, D., Brandić Mičetić, V., Fijan, S., Šikić Pogačar, M., & Pavelić, S. K. (2026). Knowledge of Dietary Supplements and Attitudes Towards Complementary Medicine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Foods, 15(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010061