Ternary Interactions of Starch, Protein, and Polyphenols in Constructing Composite Thermoplastic Starch-Based Edible Packaging: Optimization of Preparation Techniques and Investigation of Film-Formation Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Preparation of Thermoplastic Starch Films

2.4. Effects of Corn Starch, Sorbitol, Whey Protein, and Gallic Acid on the Properties of Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

2.5. Optimization of Preparation Conditions for Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

2.6. Determination of Tensile Strength and Elongation at Break

2.7. In Situ Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.8. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

2.9. Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) Analysis

2.10. Molecular Docking Simulation

2.11. Statistical

3. Results and Discussion

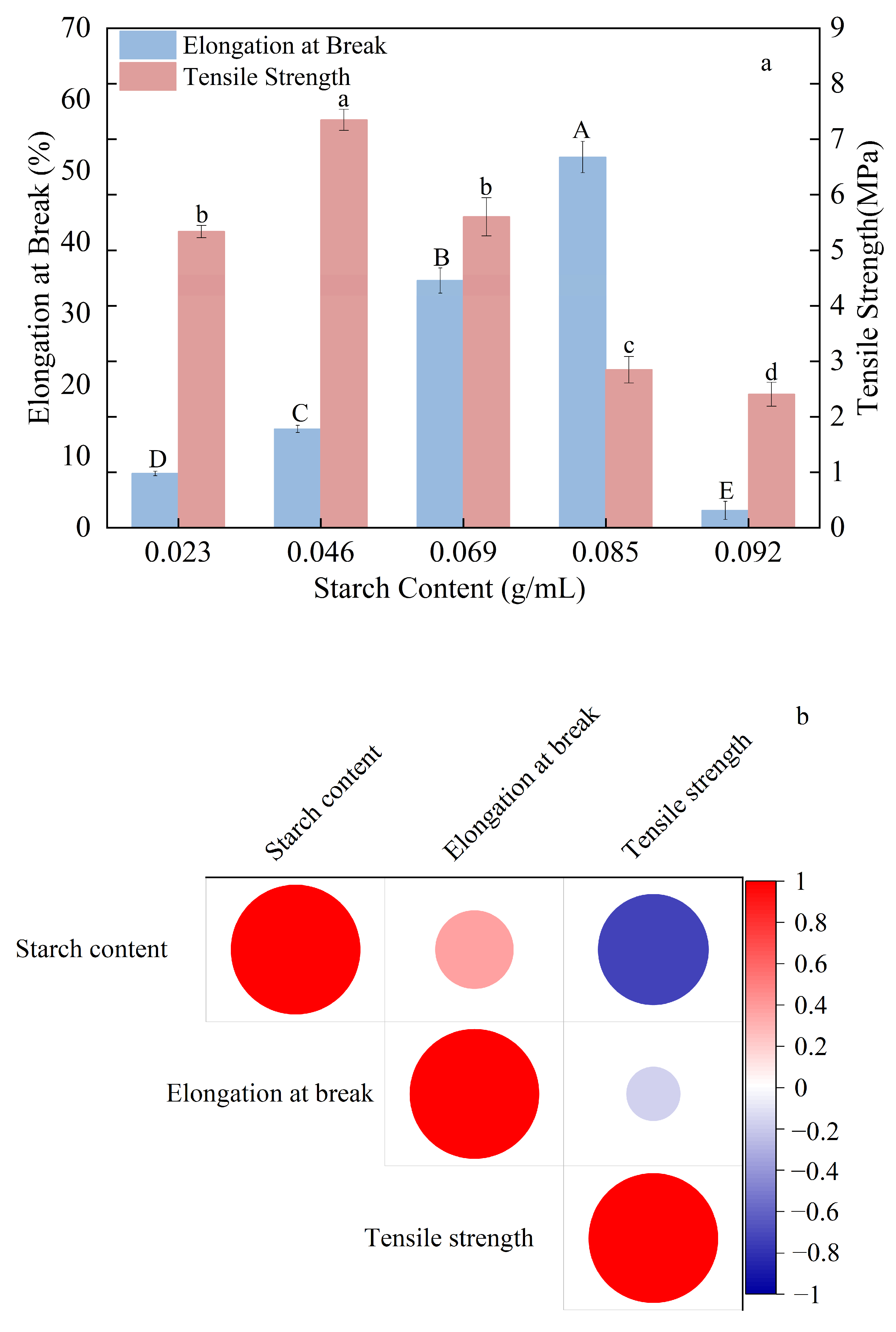

3.1. Effect of Starch Content on the Mechanical Properties of Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

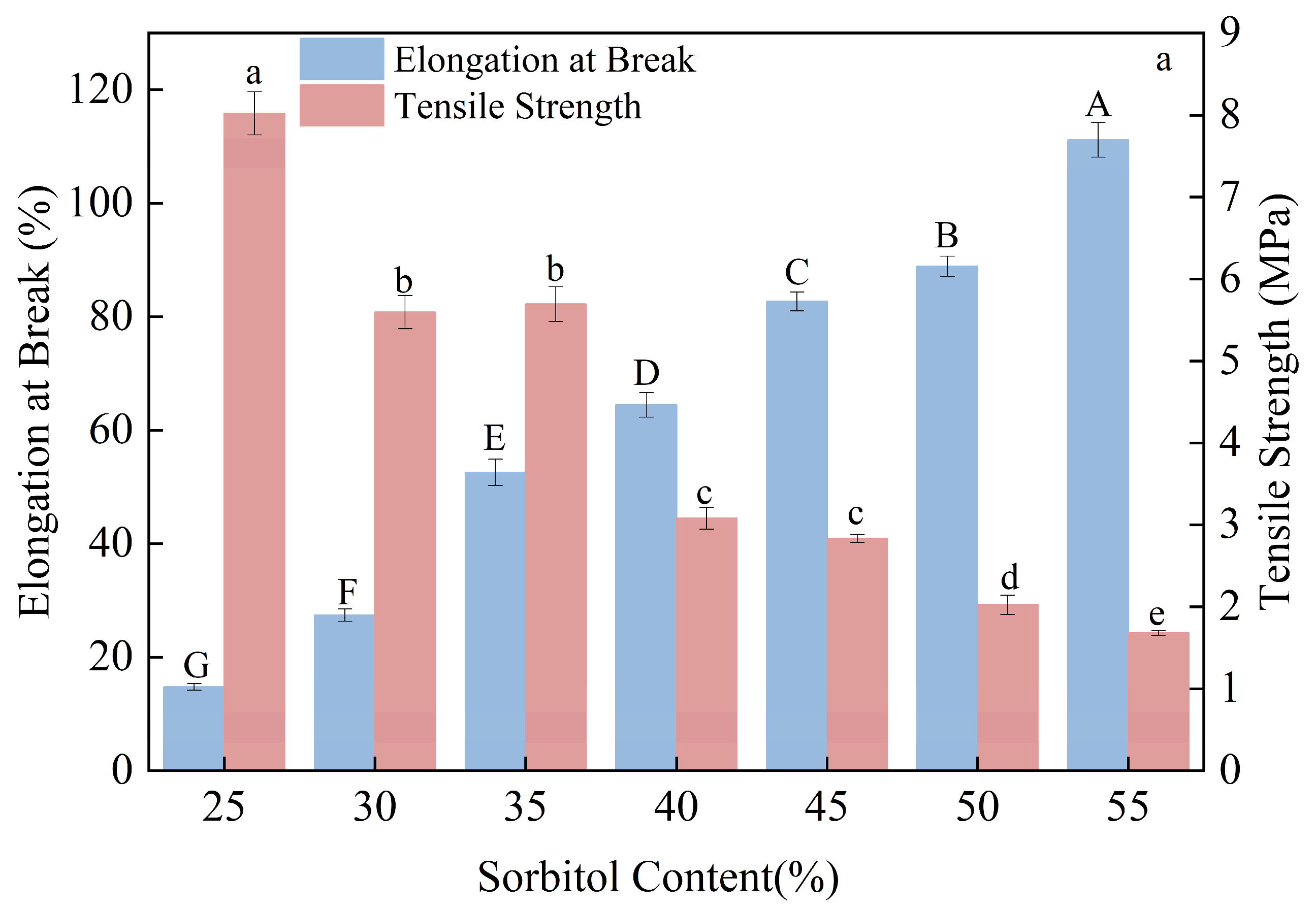

3.2. Effect of Sorbitol on the Formation Mechanism and Mechanical Behavior of Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

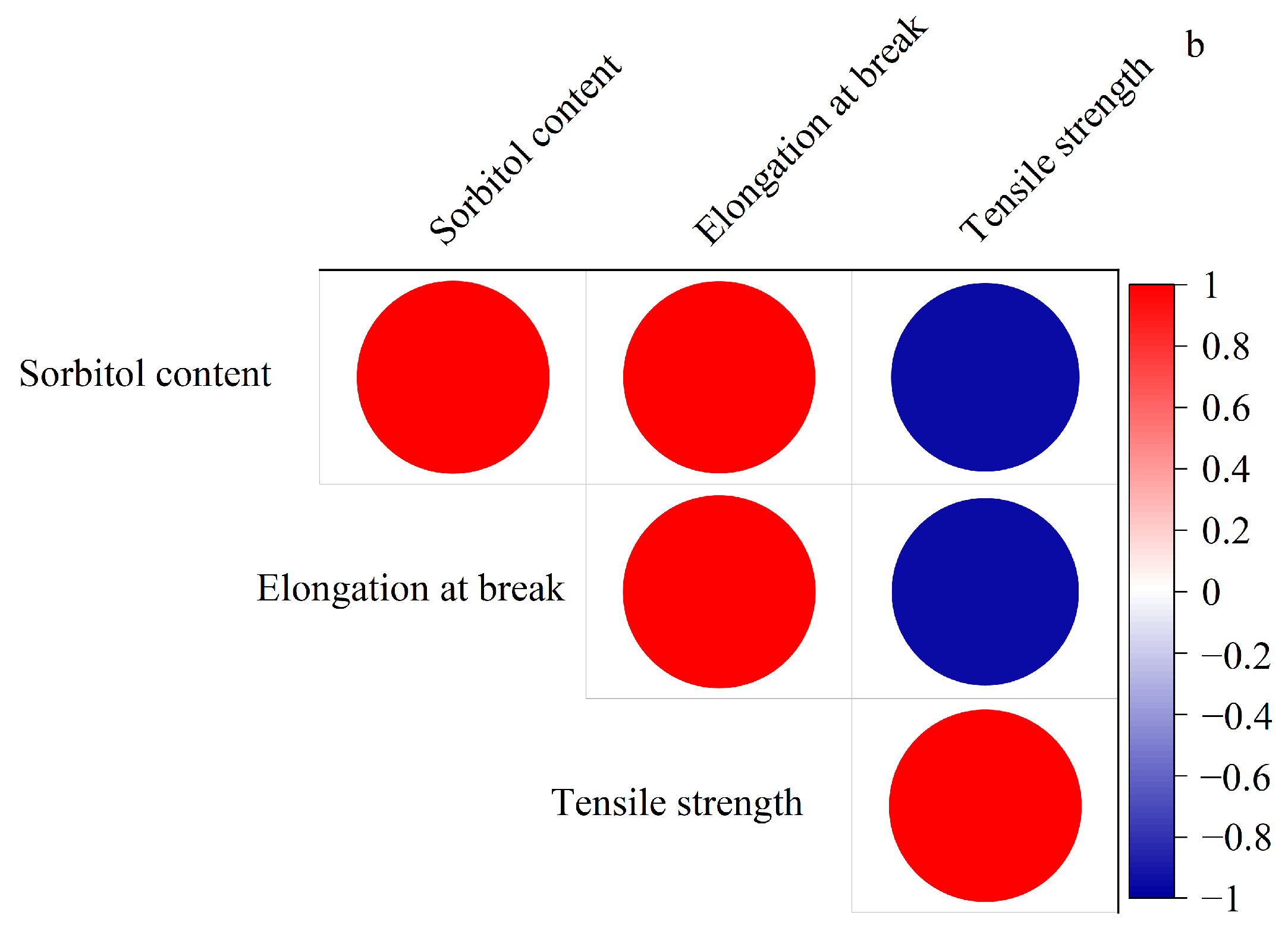

3.3. Effect of Whey Protein Isolate Content on the Mechanical Properties of Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

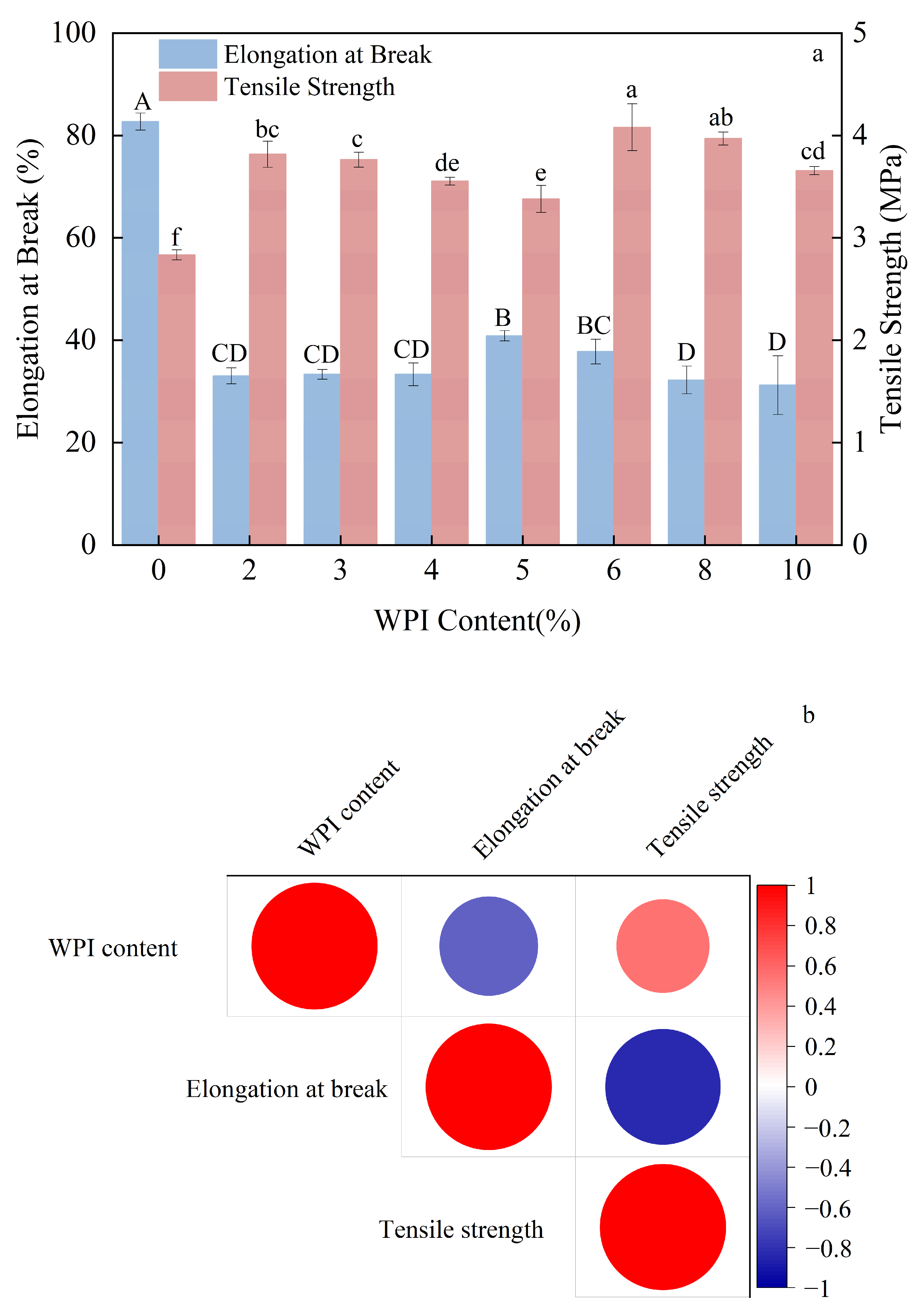

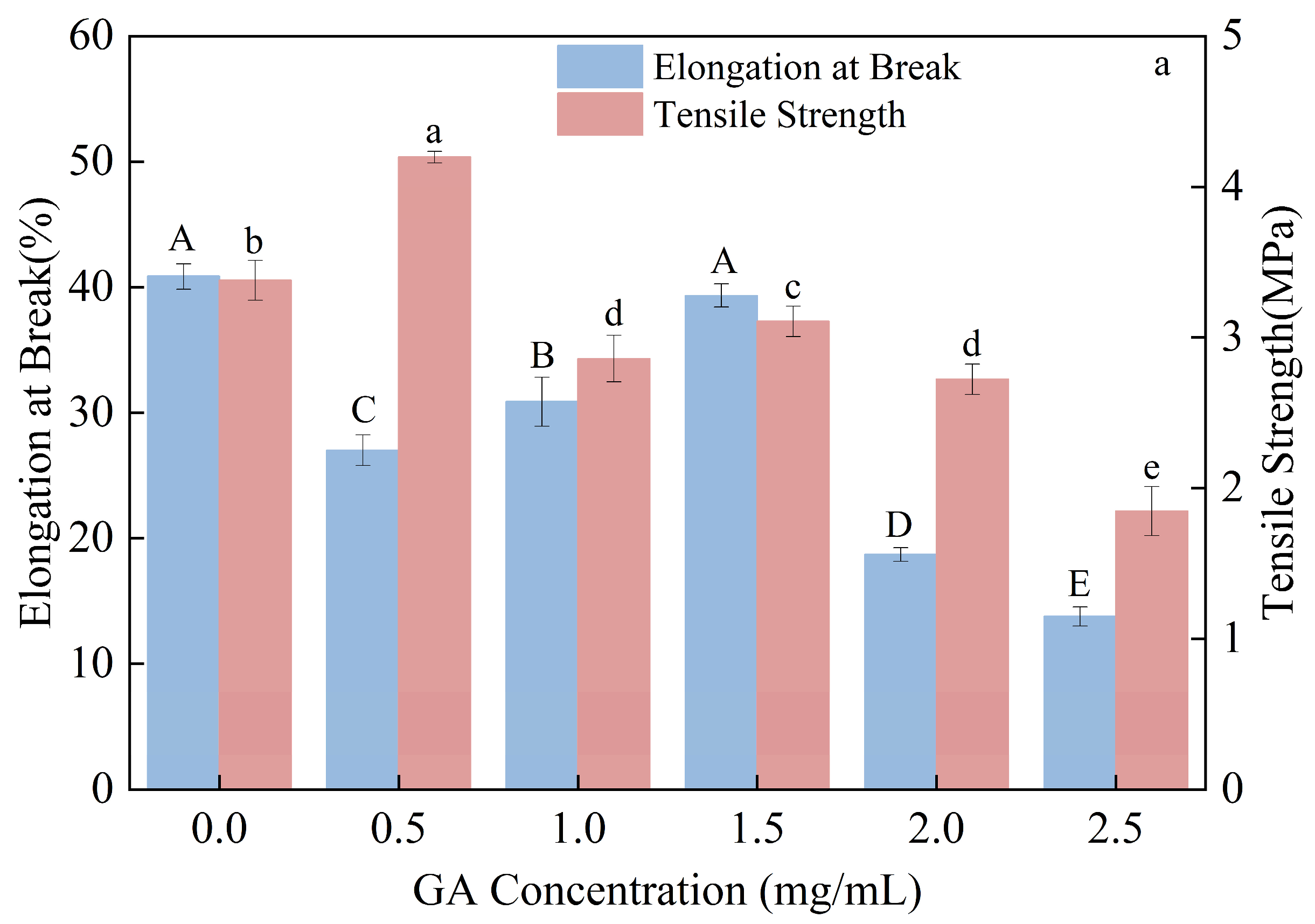

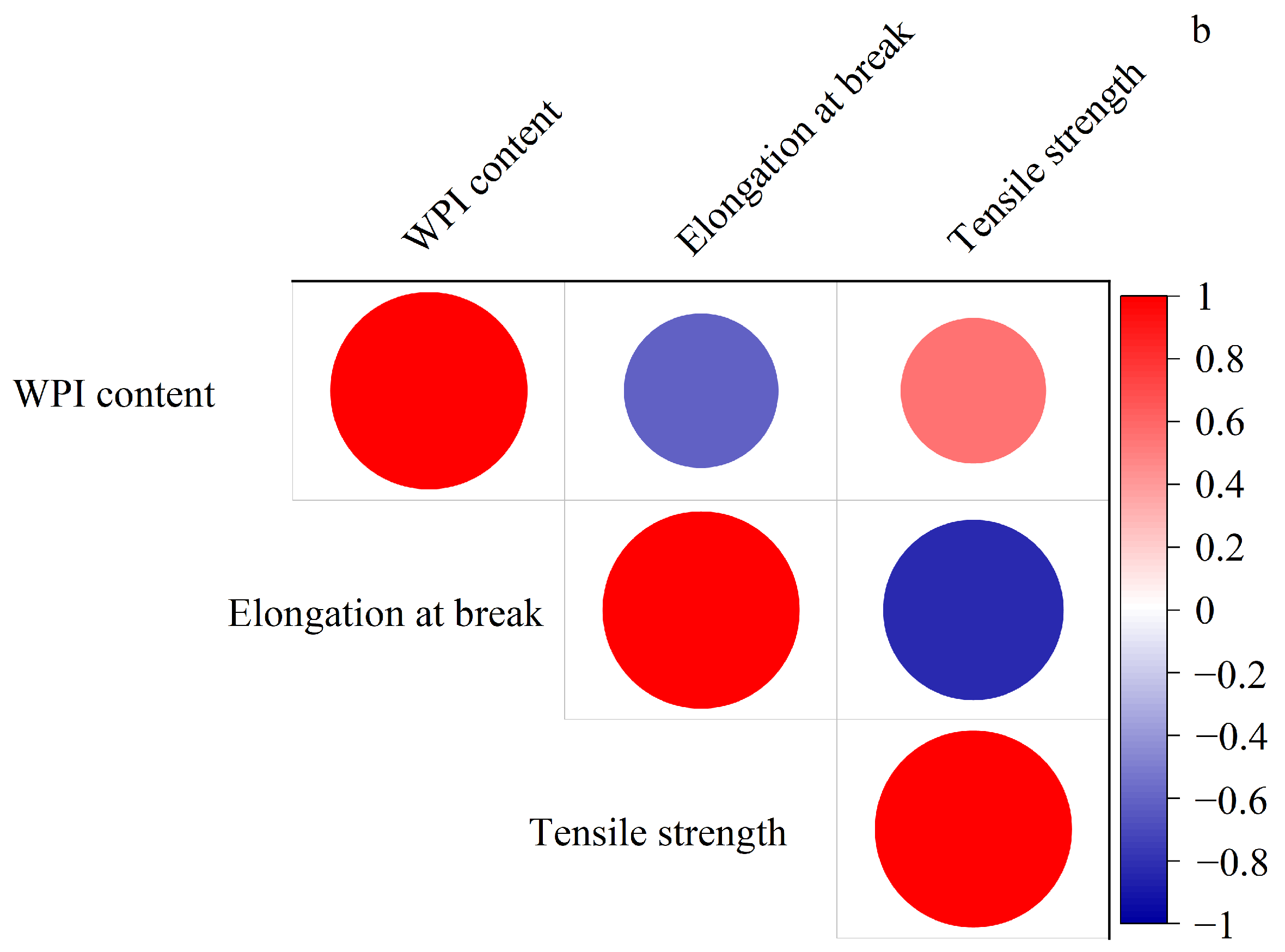

3.4. Effect of Gallic Acid Content on the Mechanical Properties of Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

3.5. Optimization and Analysis of Preparation Conditions for Composite Thermoplastic Starch Films

0.075BC + 0.0525BD + 0.175CD − 0.4229A2 − 0.5104B2 − 0.1092C2 − 0.3892D2

2.35BC + 5.25BD + 1.09CD − 4.70A2 − 4.25B2 − 4.93C2 − 4.27D2

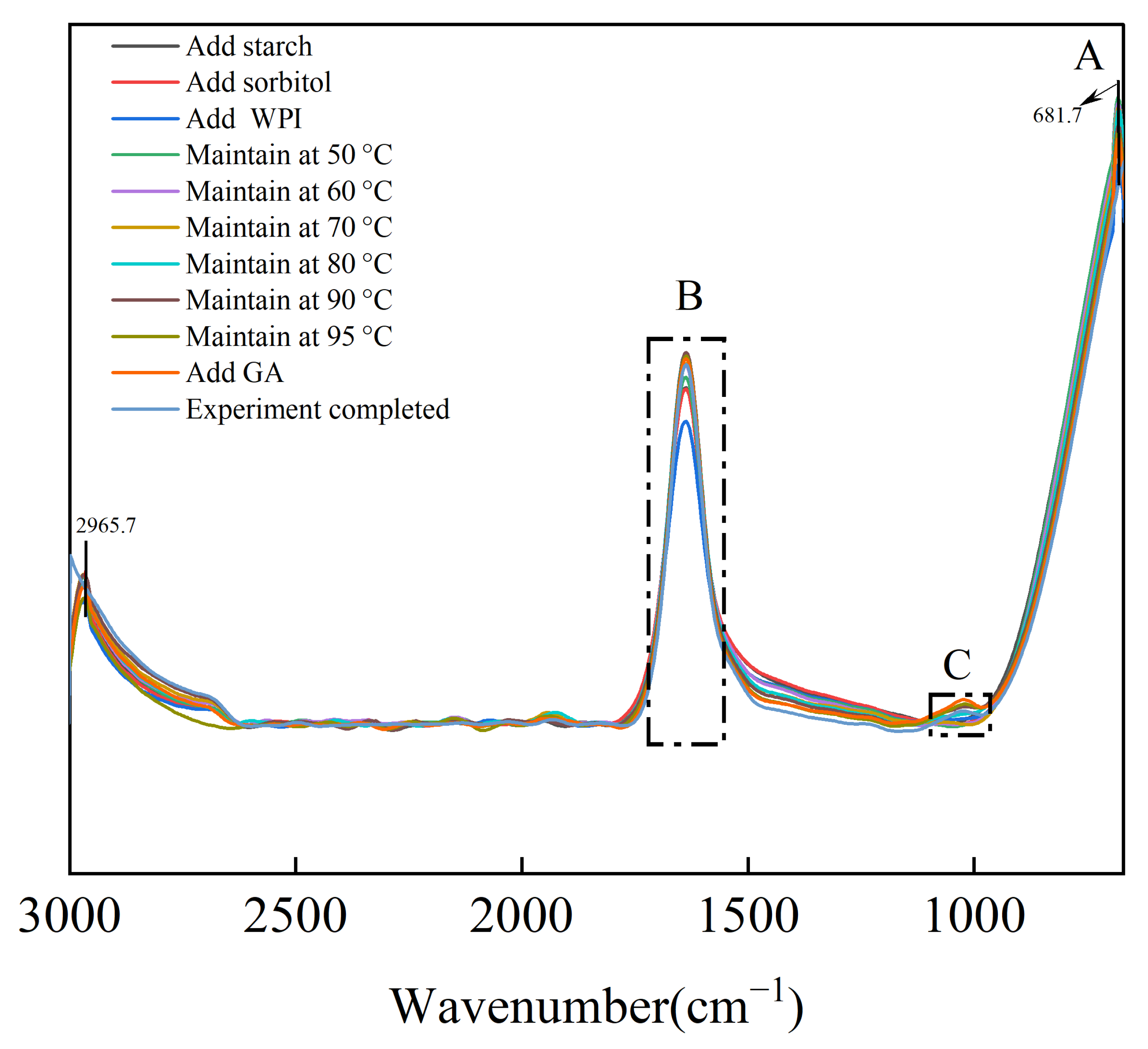

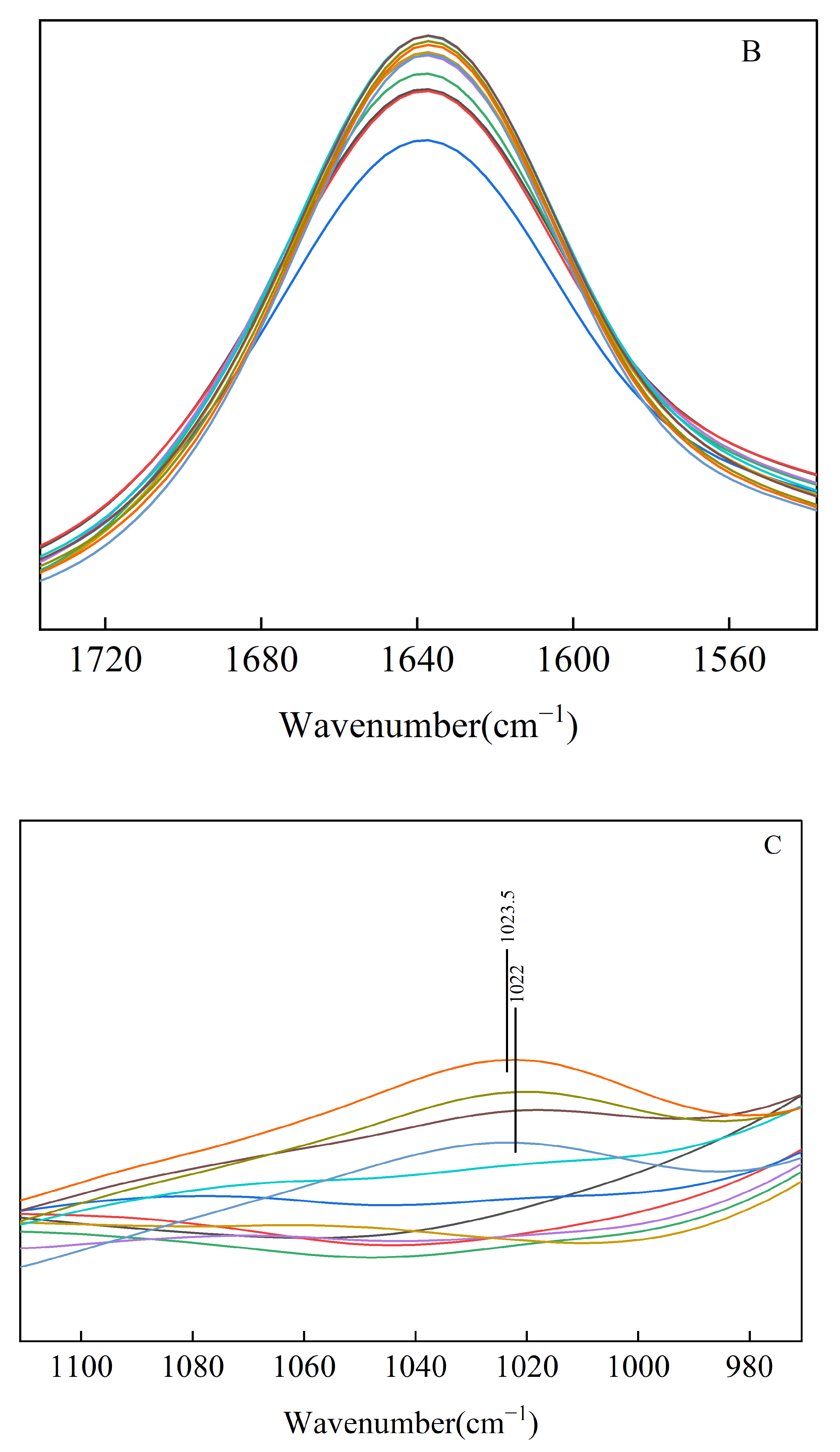

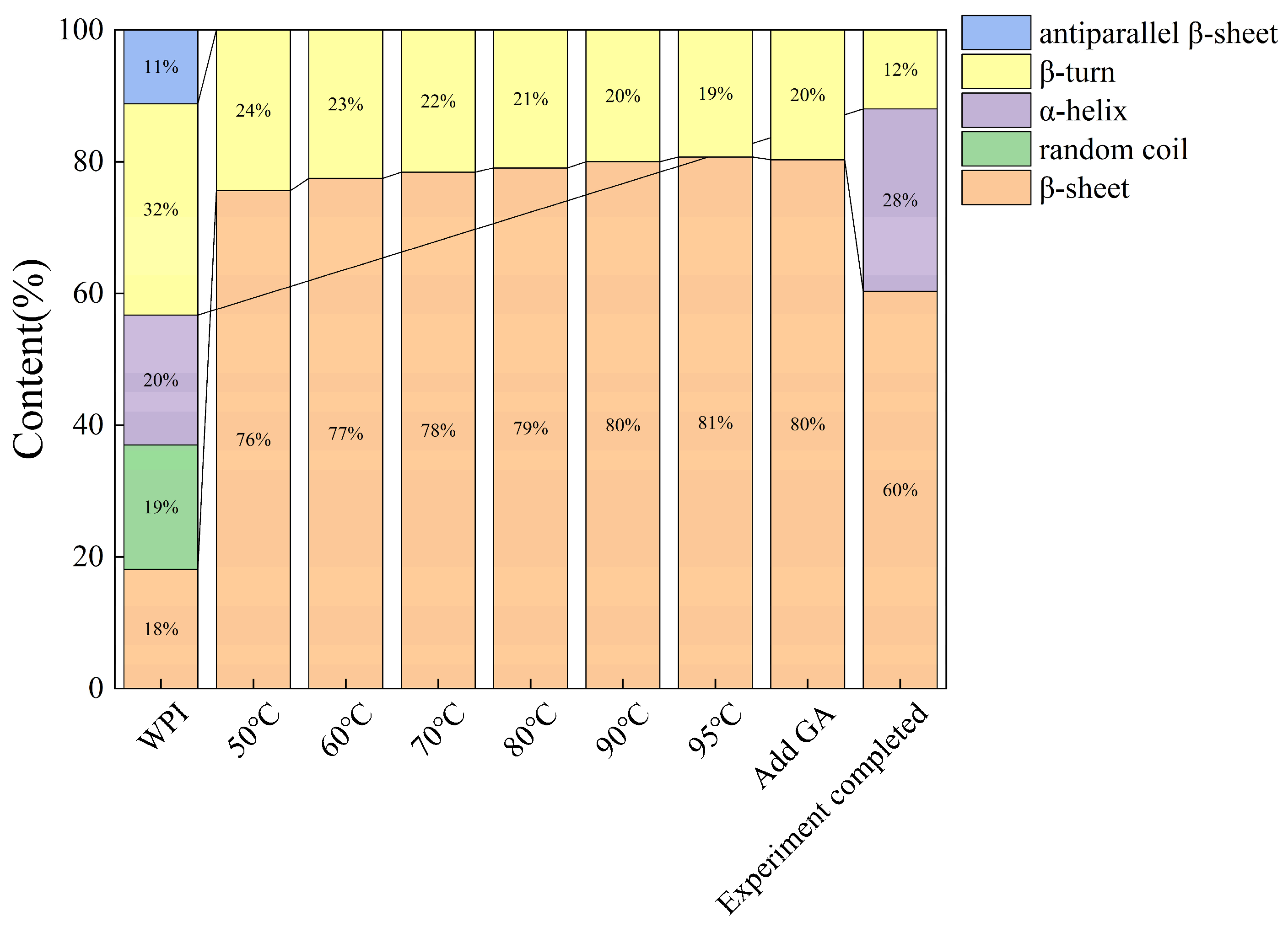

3.6. In Situ FTIR Analysis

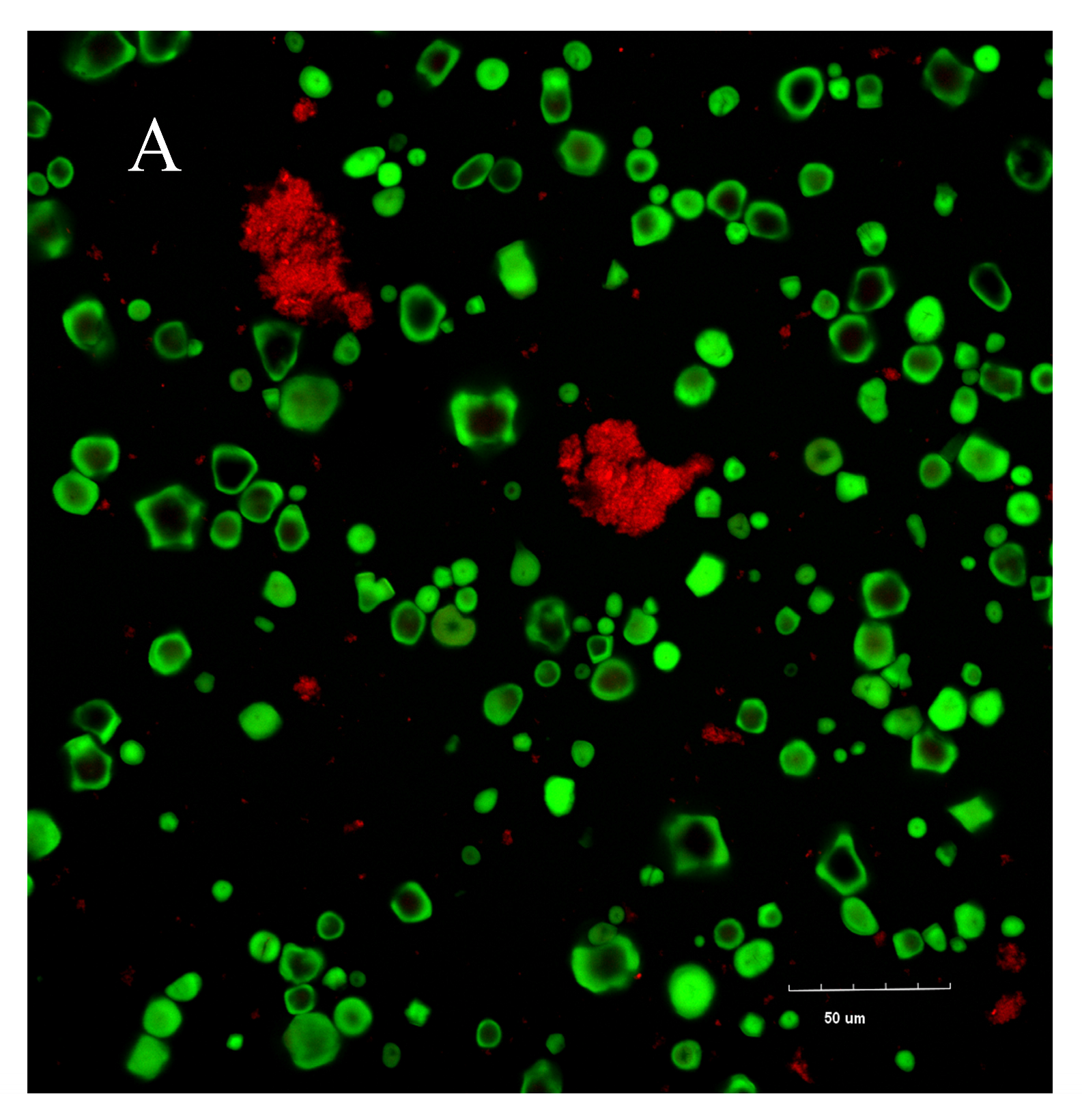

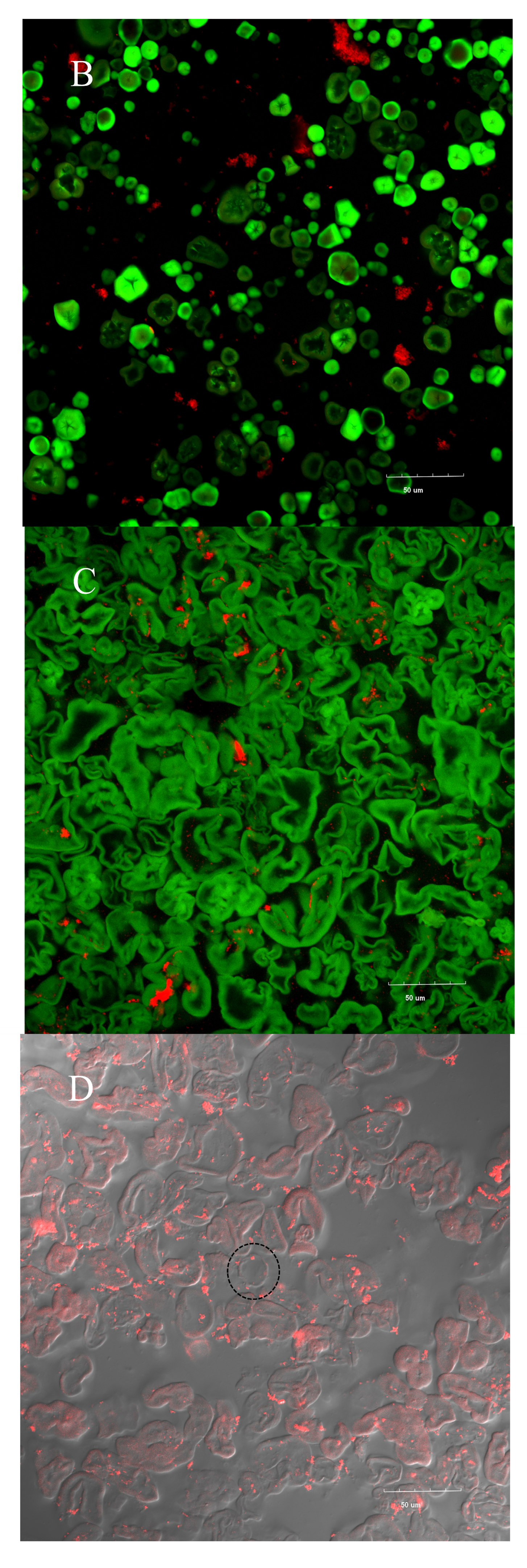

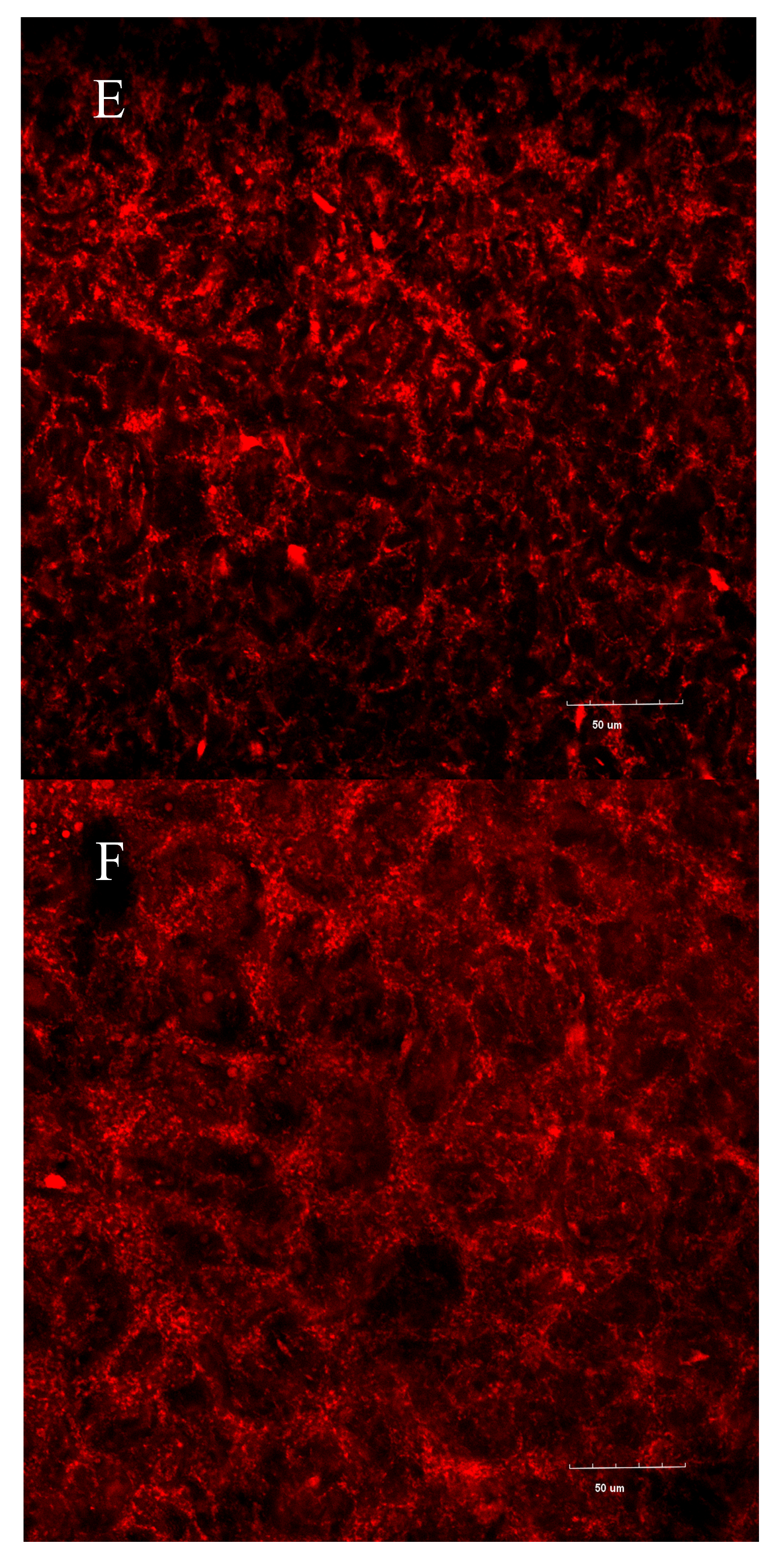

3.7. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

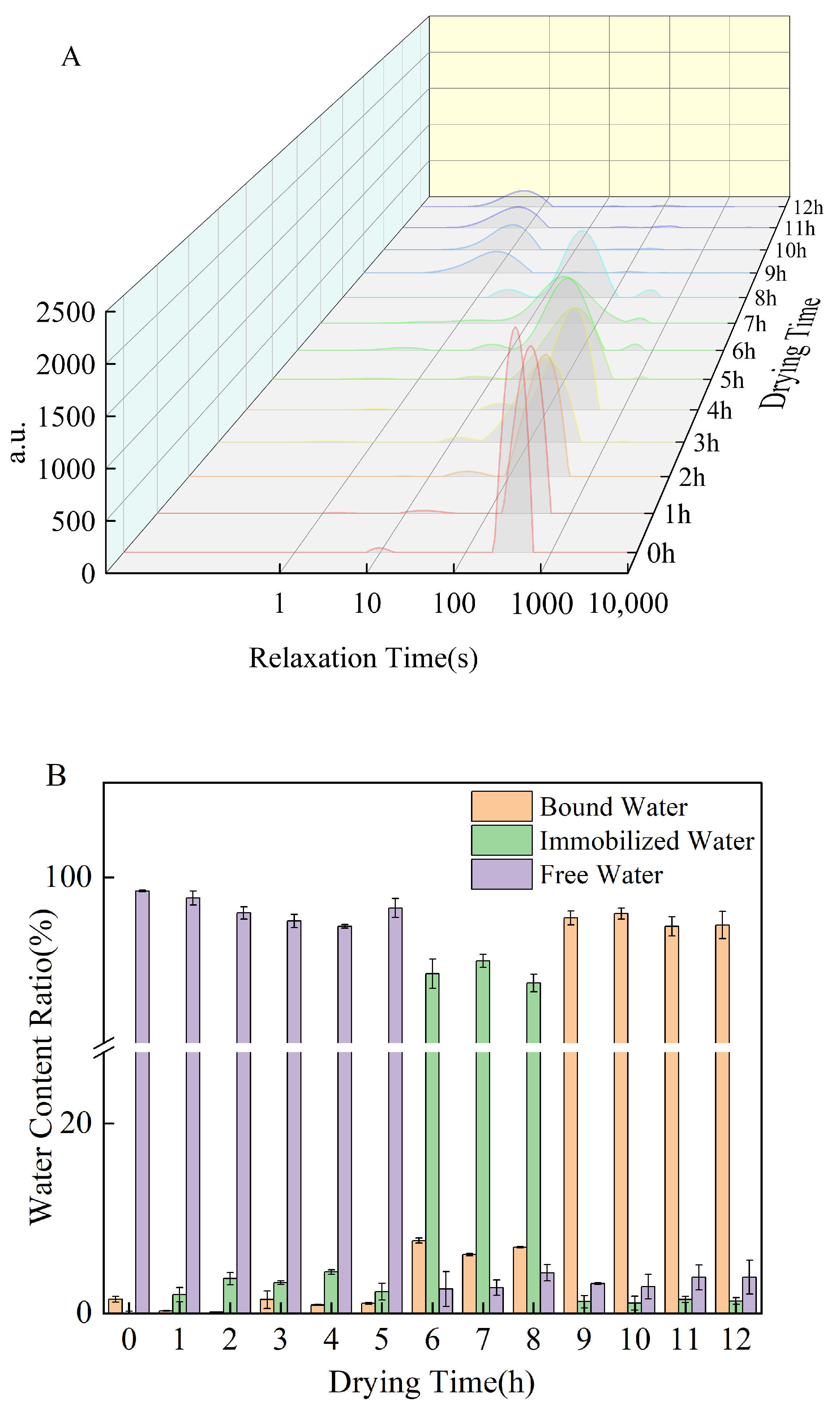

3.8. Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis

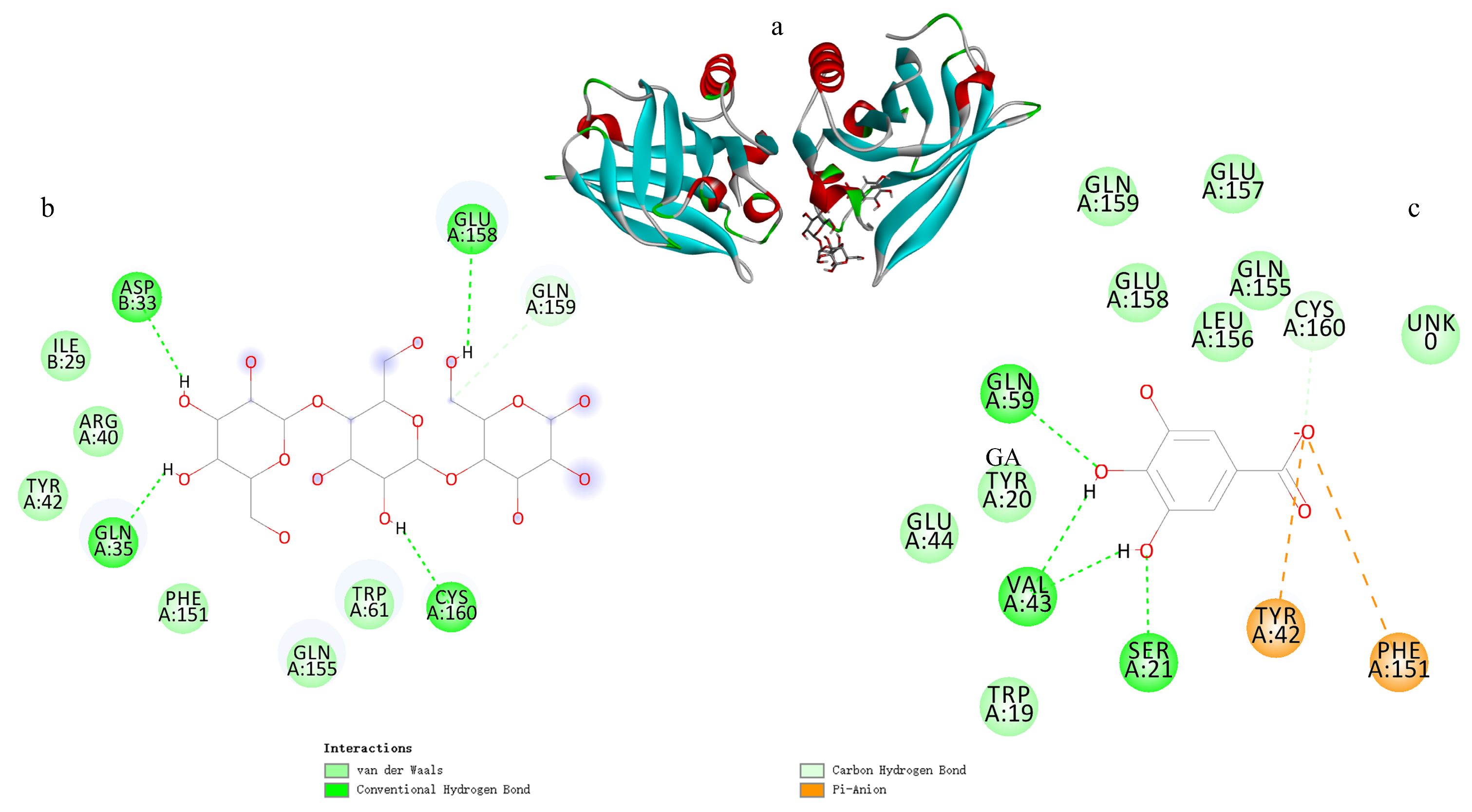

3.9. Analysis of Molecular Docking Simulation Results

3.10. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azimi, R.N.; Sonchaeng, U.; Leelaphiwat, P.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Bumbudsanpharoke, N. Comparative study of packaging performance: Thermoplastic starch blends and polyester blends for biodegradable personal care packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 145739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Ji, N.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Bioactive and intelligent starch-based films: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tânia, A.; Anna, K.; Bruno, F.A.V.; José, M.S.; Márcia, B.; Adelaide, A.; Carmen, S.R.F. Biobased ternary films of thermoplastic starch, bacterial nanocellulose and gallic acid for active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 118943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, C.C.B.; Nuno, H.C.S.S.; Lourdes, L.C.C.; Casimiro, C.M.S.; Enrique, E.J.M.; Carmen, S.R.F.; Carla, V. Biobased films of nanocellulose and mango leaf extract for active food packaging: Supercritical impregnation versus solvent casting. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 117, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Sun, Y.; Ji, N.; Dai, L.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Sun, K. Superhydrophobic chitosan films via SiO2/PDMS coating for reducing liquid food residue. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 236, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Based on surface roughness and hydrophobicity to reduce the bacterial adhesion to collagen films for the ability to enhance the shelf life of food. Food Packag. Shelf. Life 2025, 48, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxabide, A.; Carvalho, O.E.; Pereira, N.; Correia, D.; Guerrero, P.; Costa, C.M. Tuning the properties of gelatin films through crosslinking and addition of ionic liquids. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 216, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galus, S. Functional properties of soy protein isolate edible films as affected by rapeseed oil concentration. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 85, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M.K.; Smith, R.C. Recent advances in starch-based films toward food packaging applications: Physicochemical, mechanical, and functional properties. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3031–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Yan, X.; Li, F.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z. Fabrication high toughness poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/thermoplastic starch composites via melt compounding with ethylene-methyl acrylate-glycidyl methacrylate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C. Preparation of high-toughness thermoplastic starch films via enzymatic hydrolysis and cross-linking modification. Front. Environ. Res. 2025, 3, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mahardika, M.; Sudarjat, A.S.K.; Ilyas, R.A.; Mohamad, H.M.K. Revolutionizing thermoplastic starch: Advances in nanocellulose reinforced biocomposites: A review. Biomass Bioenrg 2026, 204, 108419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jia, L.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Yang, J. Study on the Mechanism of Thermoplastic Starch Using Amide Plasticize. Starch/Stärke 2025, 77, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christos-Konstantinos, M.; Vasileia, S.; Anthia, M.; Kali, K.; Costas, G.B.; Athina, L. Physicochemical properties of zein-based edible films and coatings for extending wheat bread shelf life. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107856. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, J.; Wang, C.; Shen, M.; Li, Y. Effect of aggregate size on water distribution and pore fractal characteristics during hydration of cement mortar based on low-field NMR technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 389, 131670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effects of different proportions of erythritol and mannitol on the physicochemical properties of corn starch films prepared via the flow elongation method. Food Chem. 2023, 437, 137899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P. Effect of plasticizer and antimicrobial agents on functional properties of bionanocomposite films based on corn starch-chitosan for food packaging applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, C.; Pinto, J.R.; Coelho, J.; Domingues, M.M.; Daina, S.; Sadocco, P.; Freire, S.C. Bioactive chitosan/ellagic acid films with UV-light protection for active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 73, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene-López, D.; García-Quesada, C.J.; Martin-Gullon, I.; Montalbán, M.G. Influence of Starch Composition and Molecular Weight on Physicochemical Properties of Biodegradable Film. Polymers 2019, 11, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, V.M.; Carvalho, R.A.; Borges, S.V.; Claro, P.I.C.; Hasegawa, F.K.; Yoshida, M.I.; Marconcini, J.M. Thermoplastic starch/whey protein isolate/rosemary essential oil nanocomposites obtained by extrusion process: Antioxidant polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fei, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Gong, D.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J. A combination of microwave treatment and covalent binding of gallic acid improves the solubility, emulsification and thermal stability of peanut protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2025, 206, 116105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juthathip, P.; Nathdanai, H. Oxygen absorbing food packaging made by extrusion compounding of thermoplastic cassava starch with gallic acid. Food Control 2022, 142, 109273. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sullca, C.; Vargas, M.; Atares, L.; Chiralt, A. Thermoplastic cassava starch-chitosan bilayer films containing essential oils. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Islam, S.; Kallem, P.; Patel, R.; Banat, F.; Patel, A. Potato starch-based bioplastics synthesized using glycerol–sorbitol blend as a plasticizer: Characterization and performance analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 20, 7843–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, H.; Mahdi, S.J.; Iman, K. Inorganic and metal nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity in food packaging applications. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, M.A.; El-Sayed, M.S. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: Concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 193, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaraj, V.M.; Rambabu, K.; Banat, F.; Mittal, V. Natural antioxidants-based edible active food packaging: An overview of current advancements. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lin, W.; Gao, J.; Gong, H.; Mao, X. Limited hydrolysis as a strategy to improve the non-covalent interaction of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) with whey protein isolate near the isoelectric point. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Ming, J. Interaction between wheat gliadin and quercetin under different pH conditions analyzed by multi-spectroscopy methods. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2020, 229, 117937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewelina, B.; Andrzej, L.; Frédéric, D. How Glycerol and Water Contents Affect the Structural and Functional Properties of Starch-Based Edible Films. Polymers 2018, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Jaramillo, C.; Ochoa-Yepes, O.; Bernal, C.; Famá, L. Active and smart biodegradable packaging based on starch and natural extracts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 176, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, B.S.; Scott, W.W.; Omodunbi, A.A.; Manoj, K. Recent advances in thermoplastic starches for food packaging: A review. Food Packag. Shelf. Life 2021, 30, 110743. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch-Vargas, P.R.; Aguilar-Palazuelos, E.; de Jesús Zazueta-Morales, J.; Vega-García, M.O.; Valdez-Morales, J.E.; Martínez-Bustos, F.; Jacobo-Valenzuela, N. Physicochemical and Microstructural Characterization of Corn Starch Edible Films Obtained by a Combination of Extrusion Technology and Casting Technique. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, E2224–E2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, L.; David, J.M.; Peng, X.; Xu, Z.; Jin, Z. Development of starch film to realize the value-added utilization of starch in food and biomedicine. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D882-12; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Sirbu, E.E.; Dinita, A.; Tănase, M.; Portoacă, A.I.; Bondarev, A.; Enascuta, C.E.; Calin, C. Influence of Plasticizers Concentration on Thermal, Mechanical, and Physicochemical Properties on Starch Films. Processes 2024, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranzadeh, N.; Najafi, M.; Ataeefard, M. Production of biodegradable packaging film based on PLA/starch: Optimization via response surface methodolog. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2024, 47, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jia, X.; Zhi, C.; Jin, Z.; Miao, M. Improving the properties of starch-based antimicrobial composite films using ZnO–chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 210, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Xie, M.; Wu, L. Spectroscopic and Molecular Docking Studies on the Influence of Inulin on the Interaction of Sophoricoside with Whey Protein Concentrate. Foods 2024, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, T.; Ding, W.; Xu, B. Maillard Reaction in Flour Product Processing: Mechanism, Impact on Quality, and Mitigation Strategies of Harmful Products. Foods 2025, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, H.; Ubbink, J. Reversible and irreversible changes in protein secondary structure in the heat- and shear-induced texturization of native pea protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Feng, R.; Wu, S.; Ji, Q.; Tao, H.; Xu, B.; Zhang, B. New insights into rice starch-gallic acid-whey protein isolate interactions: Effects of multiscale structural evolution and enzyme activity on starch digestibility. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 350, 123039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Eyituoyo, O.D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Meng, L.; Wei, W.; Yan, T. Impact of binding interaction modes between whey protein concentrate and quercetin on protein structural and functional characteristics. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 142, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.; Hao-Xiang, G.; Qiang, H.; Wei-Cai, Z. Potential application of phenolic compounds with different structural complexity in maize starch-based film. Food Struct. 2023, 36, 100318. [Google Scholar]

- Palomba, D.; Vazquez, E.G.; Díaz, F.M. Prediction of elongation at break for linear polymers. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2014, 139, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Cai, X.; Li, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Zeng, L. Studies on the interactions of theaflavin-3,3′-digallate with bovine serum albumin: Multi-spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, D.; Françoise, B. Thermogravimetric, Morphological and Infrared Analysis of Blends Involving Thermoplastic Starch and Poly (ethylene-co-methacrylic acid) and Its Ionomer Form. Molecule 2023, 28, 4519. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, X.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, N. Characterizing the chemical features of lipid and protein in sweet potato and maize starches. Starch/Stärke 2014, 66, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Yu, M.; Yin, H.; Peng, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, S. Multiscale structures, physicochemical properties, and in vitro digestibility of oat starch complexes co-gelatinized with jicama non-starch polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Gao, X.; Hao, M.; Tang, L. Comparison of binding interaction between β-lactoglobulin and three common polyphenols using multi-spectroscopy and modeling methods. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Tang, H.; Yu, D.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L. Effect of anionic polysaccharides on conformational changes and antioxidant properties of protein-polyphenol binary covalently-linked complexes. Process Biochem. 2020, 89, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shen, Q.; Hu, L.; Hu, Y.; Ye, X. Physicochemical properties, structure and in vitro digestibility on complex of starch with lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) leaf flavonoids. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, M. Dynamics of water mobility and distribution in soybean antioxidant peptide powders monitored by LF-NMR. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pylaeva, S.; Brehm, M.; Sebastiani, D. Salt Bridge in Aqueous Solution Strong Structural Motifs but Weak Enthalpic Effect. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Yuan, C.; Wu, L. Application of spectroscopic techniques combined with molecular docking for the study of the interactions between bovine lactoferrin, 20-carbon unsaturated fatty acid, and rutin. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, vvaf001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch Content(A)/ g/mL | Sorbitol Content (w/w) (B)/ % | Whey Protein Isolate Content (w/w) (C)/ % | Gallic Acid Content (D)/ mg/mL | |

| −1 | 0.062 | 40 | 4 | 1.0 |

| 0 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 |

| 1 | 0.077 | 50 | 6 | 2.0 |

| Run No. | Starch Content (g/mL) | Sorbitol Content (w/w %) | WPI Content (w/w %) | GA Concentration (mg/mL) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.069 | 45 | 6 | 1.0 | 3.23 ± 0.02 fghi | 31.14 ± 0.17 ijkl |

| 2 | 0.077 | 45 | 6 | 1.5 | 3.71 ± 0.13 bcd | 37.22 ± 1.15 fg |

| 3 | 0.062 | 45 | 6 | 1.5 | 3.16 ± 0.07 ghij | 33.10 ± 1.33 hijkl |

| 4 | 0.069 | 45 | 4 | 1.0 | 3.57 ± 0.29 cde | 36.88 ± 1.64 fgh |

| 5 | 0.069 | 50 | 5 | 2.0 | 2.89 ± 0.01 jkl | 43.37 ± 2.11 bc |

| 6 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.97 ± 0.08 ab | 46.34 ± 3.08 ab |

| 7 | 0.069 | 50 | 5 | 1.5 | 2.84 ± 0.12 lm | 36.52 ± 1.54 fgh |

| 8 | 0.062 | 45 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.12 ± 0.07 hijk | 41.85 ± 0.98 cde |

| 9 | 0.069 | 45 | 4 | 2.0 | 3.01 ± 0.09 ijkl | 36.38 ± 1.65 fgh |

| 10 | 0.069 | 40 | 5 | 1.0 | 3.28 ± 0.38 fghi | 30.72 ± 0.18 jkl |

| 11 | 0.062 | 45 | 5 | 2.0 | 2.92 ± 0.02 jkl | 31.46 ± 2.92 ijkl |

| 12 | 0.069 | 50 | 4 | 1.5 | 2.96 ± 0.10 jkl | 33.01 ± 2.53 ijkl |

| 13 | 0.062 | 45 | 5 | 1.0 | 2.60 ± 0.15 m | 39.21 ± 1.69 def |

| 14 | 0.069 | 45 | 6 | 2.0 | 3.37 ± 0.03 efgh | 34.99 ± 3.48 ghi |

| 15 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 | 4.10 ± 0.19 a | 39.82 ± 3.78 cdef |

| 16 | 0.077 | 45 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.61 ± 0.09 cde | 29.48 ± 2.26 lm |

| 17 | 0.077 | 45 | 5 | 1.0 | 3.43 ± 0.05 efg | 26.59 ± 2.86 m |

| 18 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.74 ± 0.16 bcd | 42.89 ± 2.55 bcd |

| 19 | 0.069 | 50 | 6 | 1.5 | 2.79 ± 0.05 lm | 38.87 ± 2.34 ef |

| 20 | 0.062 | 40 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.26 ± 0.07 fghi | 33.69 ± 0.97 ghijk |

| 21 | 0.069 | 50 | 5 | 1.0 | 2.60 ± 0.07 m | 37.58 ± 1.76 fg |

| 22 | 0.069 | 40 | 6 | 1.5 | 3.48 ± 0.12 def | 30.54 ± 1.45 jkl |

| 23 | 0.077 | 45 | 5 | 2.0 | 2.86 ± 0.06 klm | 40.04 ± 2.78 cdef |

| 24 | 0.069 | 40 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.35 ± 0.04 efgh | 34.07 ± 1.38 ghij |

| 25 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.76 ± 0.14 bc | 43.02 ± 0.67 bcd |

| 26 | 0.069 | 45 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.58 ± 0.40 cde | 48.55 ± 1.84 a |

| 27 | 0.069 | 40 | 5 | 2.0 | 3.36 ± 0.03 efgh | 34.41 ± 0.74 ghij |

| 28 | 0.077 | 40 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.14 ± 0.15 hij | 30.12 ± 2.49 klm |

| 29 | 0.062 | 50 | 5 | 1.5 | 2.20 ± 0.08 n | 40.07 ± 1.38 cdef |

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4.88 | 14 | 0.3484 | 11.31 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A—Starch Content | 0.4524 | 1 | 0.4524 | 14.68 | 0.0018 | ** |

| B—Plasticizer Content | 1.07 | 1 | 1.07 | 34.85 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C—WPI Content | 0.0012 | 1 | 0.0012 | 0.0389 | 0.8464 | |

| D—GA Concentration | 0.0075 | 1 | 0.0075 | 0.2434 | 0.6294 | |

| AB | 0.1444 | 1 | 0.1444 | 4.69 | 0.0482 | * |

| AC | 0.0009 | 1 | 0.0009 | 0.0292 | 0.8668 | |

| AD | 0.1980 | 1 | 0.1980 | 6.43 | 0.0238 | * |

| BC | 0.0225 | 1 | 0.0225 | 0.7301 | 0.4072 | |

| BD | 0.0110 | 1 | 0.0110 | 0.3578 | 0.5593 | |

| CD | 0.1225 | 1 | 0.1225 | 3.98 | 0.0660 | |

| A2 | 1.16 | 1 | 1.16 | 37.65 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 1.69 | 1 | 1.69 | 54.84 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C2 | 0.0773 | 1 | 0.0773 | 2.51 | 0.1356 | |

| D2 | 0.9824 | 1 | 0.9824 | 31.88 | <0.0001 | ** |

| Residual | 0.4314 | 14 | 0.0308 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.2634 | 10 | 0.0263 | 0.6272 | 0.7499 | |

| Pure Error | 0.1680 | 4 | 0.0420 | |||

| Total Variation | 5.31 | 28 |

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 721.29 | 14 | 51.52 | 8.38 | 0.0001 | ** |

| A—Starch Content | 31.40 | 1 | 31.40 | 5.11 | 0.0403 | * |

| B—Plasticizer Content | 107.22 | 1 | 107.22 | 17.45 | 0.0009 | ** |

| C—WPI Content | 2.81 | 1 | 2.81 | 0.4577 | 0.5097 | |

| D-GA Concentration | 28.61 | 1 | 28.61 | 4.66 | 0.0488 | * |

| AB | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.9968 | |

| AC | 67.98 | 1 | 67.98 | 11.06 | 0.0050 | ** |

| AD | 112.36 | 1 | 112.36 | 18.28 | 0.0008 | ** |

| BC | 22.04 | 1 | 22.04 | 3.59 | 0.0791 | |

| BD | 1.10 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.1794 | 0.6783 | |

| CD | 4.73 | 1 | 4.73 | 0.7697 | 0.3951 | |

| A2 | 143.15 | 1 | 143.15 | 23.29 | 0.0003 | ** |

| B2 | 116.91 | 1 | 116.91 | 19.02 | 0.0007 | ** |

| C2 | 157.36 | 1 | 157.36 | 25.60 | 0.0002 | ** |

| D2 | 118.29 | 1 | 118.29 | 19.25 | 0.0006 | ** |

| Residual | 86.05 | 14 | 6.15 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 40.28 | 10 | 4.03 | 0.3521 | 0.9177 | |

| Pure Error | 45.77 | 4 | 11.44 | |||

| Total Variation | 807.33 | 28 |

| Experimental Process | Short-Range Order (DO) of Starch (1047 cm−1/1022 cm−1) |

|---|---|

| Native Starch | 0.90 ± 0.00 h |

| Add WPI | 0.97 ± 0.00 c |

| 50 °C | 0.97 ± 0.00 c |

| 60 °C | 0.97 ± 0.00 b |

| 70 °C | 0.97 ± 0.00 a |

| 80 °C | 0.97 ± 0.00 d |

| 90 °C | 0.95 ± 0.00 e |

| 95 °C | 0.94 ± 0.00 g |

| Add GA | 0.95 ± 0.00 f |

| Experiment completed | 0.95 ± 0.01 f |

| Drying Time (h) | Peak Time (ms) | Peak Area (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T21 | T22 | T23 | A21 | A22 | A23 | |

| 0 | 9.42 ± 0.34 a | 0.12 ± 0.21 k | 384.47 ± 2.43 c | 1.43 ± 0.00 f | 0.00 ± 0.00 i | 97.07 ± 2.13 ab |

| 1 | 2.20 ± 1.02 de | 16.93 ± 0.14 g | 332.19 ± 1.33 d | 0.25 ± 0.01 h | 1.90 ± 0.38 fg | 97.85 ± 0.03 a |

| 2 | 4.45 ± 0.53 c | 29.04 ± 0.41 d | 290.55 ± 0.86 e | 0.14 ± 0.01 h | 3.57 ± 0.76 e | 96.29 ± 0.81 b |

| 3 | 0.98 ± 0.10 ef | 13.16 ± 0.58 h | 506.21 ± 1.34 a | 1.14 ± 0.37 fg | 3.20 ± 0.14 e | 95.67 ± 0.36 bc |

| 4 | 1.20 ± 0.91 ef | 23.51 ± 0.44 e | 218.98 ± 0.93 f | 0.86 ± 0.01 g | 4.43 ± 0.15 d | 94.72 ± 0.14 c |

| 5 | 6.70 ± 0.48 b | 1.90 ± 0.36 j | 134.64 ± 0.64 i | 1.03 ± 0.40 fg | 2.24 ± 0.07 f | 96.74 ± 0.05 ab |

| 6 | 1.14 ± 0.49 ef | 11.57 ± 0.67 i | 219.07 ± 0.81 f | 3.13 ± 0.45 e | 94.76 ± 0.56 a | 2.11 ± 0.61 e |

| 7 | 1.89 ± 0.86 ef | 33.93 ± 0.32 c | 409.23 ± 1.46 b | 6.13 ± 0.37 d | 91.01 ± 0.24 b | 2.86 ± 0.28 de |

| 8 | 3.21 ± 0.35 d | 36.15 ± 0.04 b | 384.62 ± 2.64 c | 7.01 ± 0.11 c | 89.15 ± 0.44 c | 3.84 ± 0.55 d |

| 9 | 1.63 ± 0.72 ef | 18.64 ± 0.85 f | 110.07 ± 0.53 j | 95.32 ± 0.57 b | 1.64 ± 0.63 fgh | 3.04 ± 0.06 de |

| 10 | 1.54 ± 0.70 ef | 50.53 ± 0.82 a | 145.49 ± 0.96 h | 96.35 ± 0.23 a | 1.12 ± 0.97 h | 2.54 ± 0.33 de |

| 11 | 0.97 ± 0.39 ef | 32.94 ± 1.07 c | 192.10 ± 1.33 g | 94.93 ± 0.14 b | 1.39 ± 0.53 gh | 3.69 ± 0.09 d |

| 12 | 0.57 ± 0.12 f | 15.95 ± 0.34 g | 103.35 ± 1.42 k | 95.11 ± 0.20 b | 1.30 ± 0.63 gh | 3.59 ± 0.26 de |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L. Ternary Interactions of Starch, Protein, and Polyphenols in Constructing Composite Thermoplastic Starch-Based Edible Packaging: Optimization of Preparation Techniques and Investigation of Film-Formation Mechanisms. Foods 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010036

Wang A, Zhang J, Wu L. Ternary Interactions of Starch, Protein, and Polyphenols in Constructing Composite Thermoplastic Starch-Based Edible Packaging: Optimization of Preparation Techniques and Investigation of Film-Formation Mechanisms. Foods. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Anna, Jingyuan Zhang, and Ligen Wu. 2026. "Ternary Interactions of Starch, Protein, and Polyphenols in Constructing Composite Thermoplastic Starch-Based Edible Packaging: Optimization of Preparation Techniques and Investigation of Film-Formation Mechanisms" Foods 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010036

APA StyleWang, A., Zhang, J., & Wu, L. (2026). Ternary Interactions of Starch, Protein, and Polyphenols in Constructing Composite Thermoplastic Starch-Based Edible Packaging: Optimization of Preparation Techniques and Investigation of Film-Formation Mechanisms. Foods, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010036