Improvement of Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice by Extrusion Combined with Solid-State Fermentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Black Rice Preparation and Subsequent Solid-State Fermentation

2.2.1. Preparation of Black Rice Samples

2.2.2. Solid-State Fermentation (SSF) of Black Rice Samples

2.3. In Vitro Simulated Oral-Gastric-Intestinal Phase Digestion

2.3.1. Preparation of Simulated Digestive Fluid

2.3.2. In Vitro Simulated Digestion

2.3.3. In Vitro Digestibility of Phenolic Compounds

2.4. In Vitro Simulated Large Bowel Fermentation and Metabolite Analyses

2.4.1. In Vitro Fecal Fermentation

2.4.2. Determination of Gas Production, pH, and SCFAs

2.4.3. The 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing of Gut Microbiota

2.4.4. Microbiome Bioinformatics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

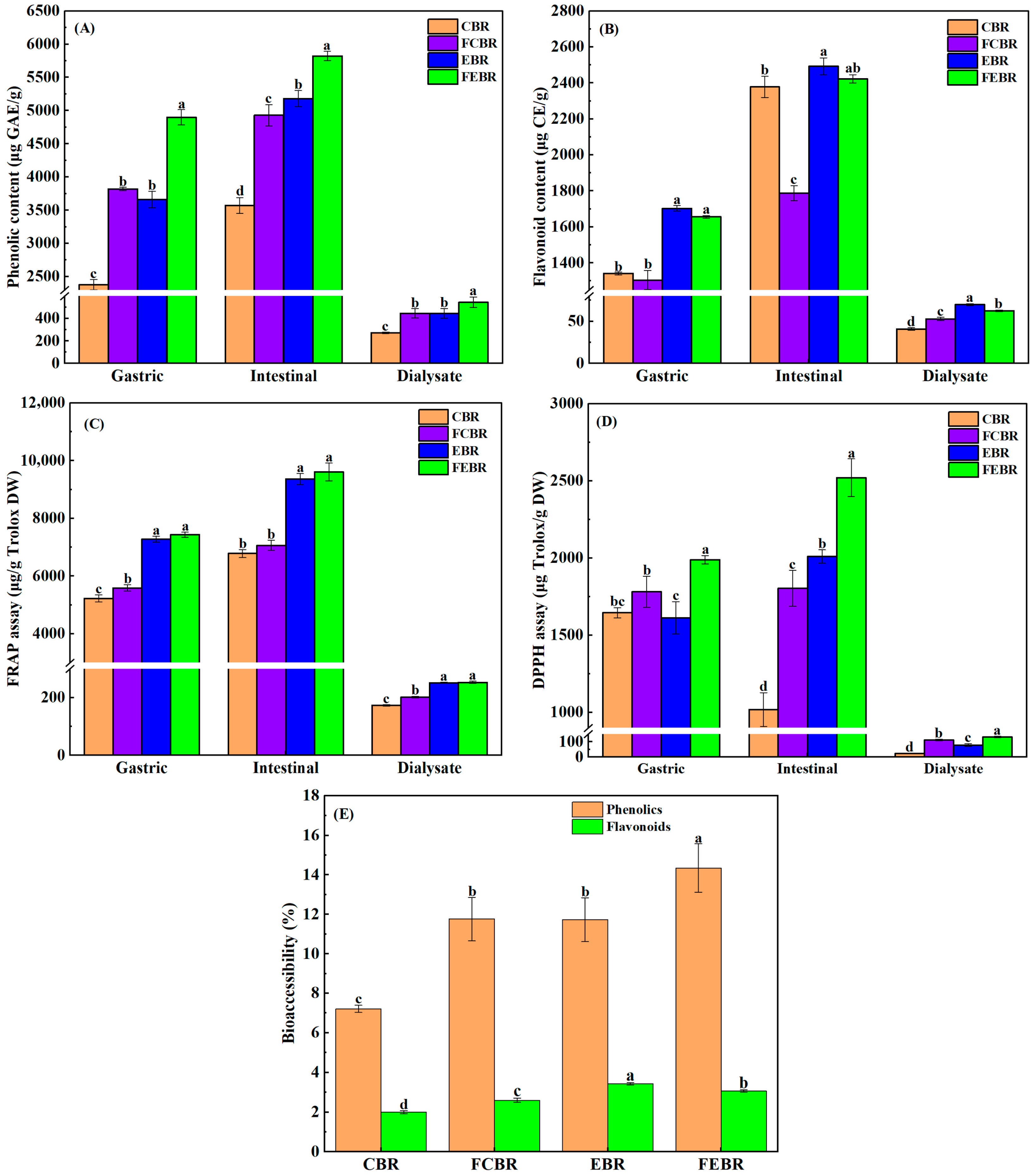

3.1. Phenolic Bioaccessibility of Black Rice During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

3.1.1. Variation of Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Activities

3.1.2. Bioaccessibility of Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Phenolic Acids

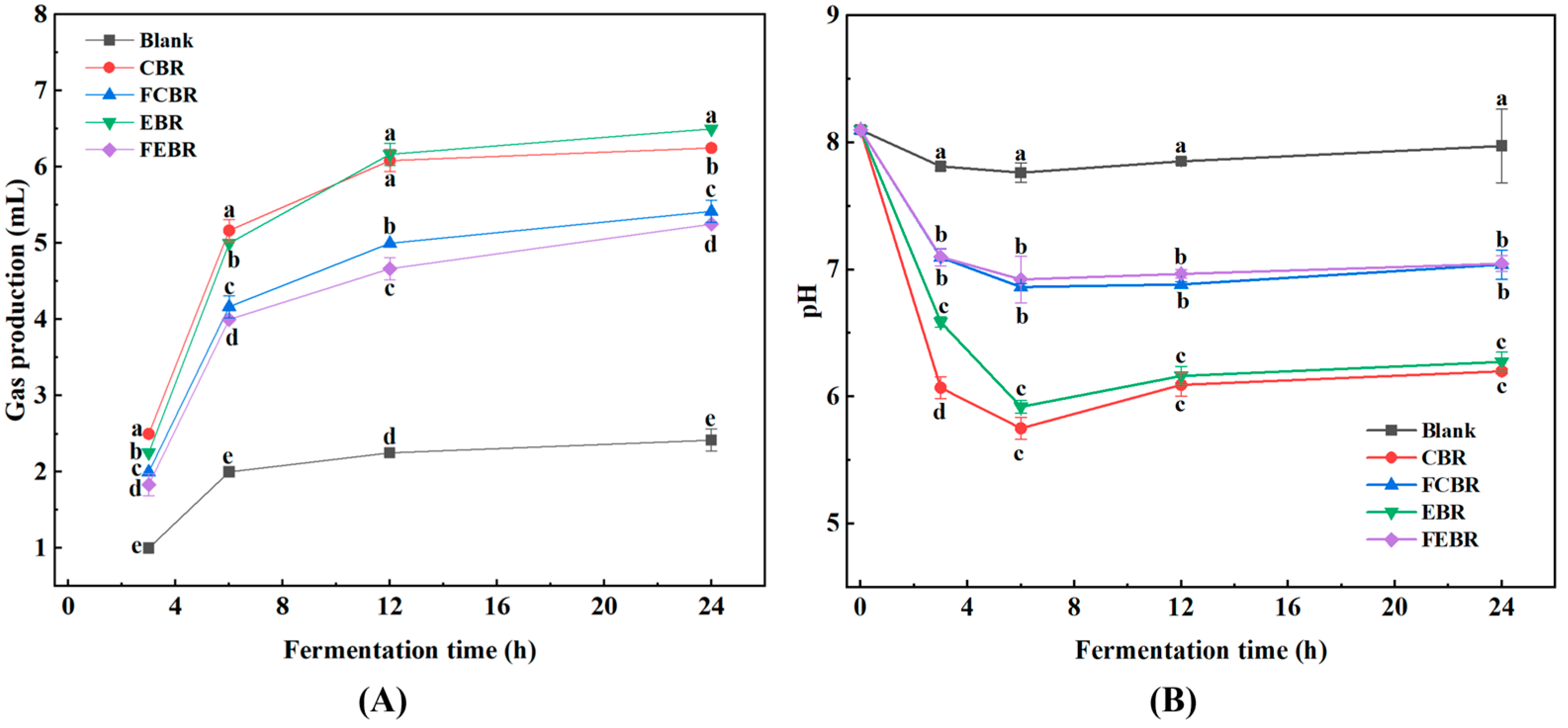

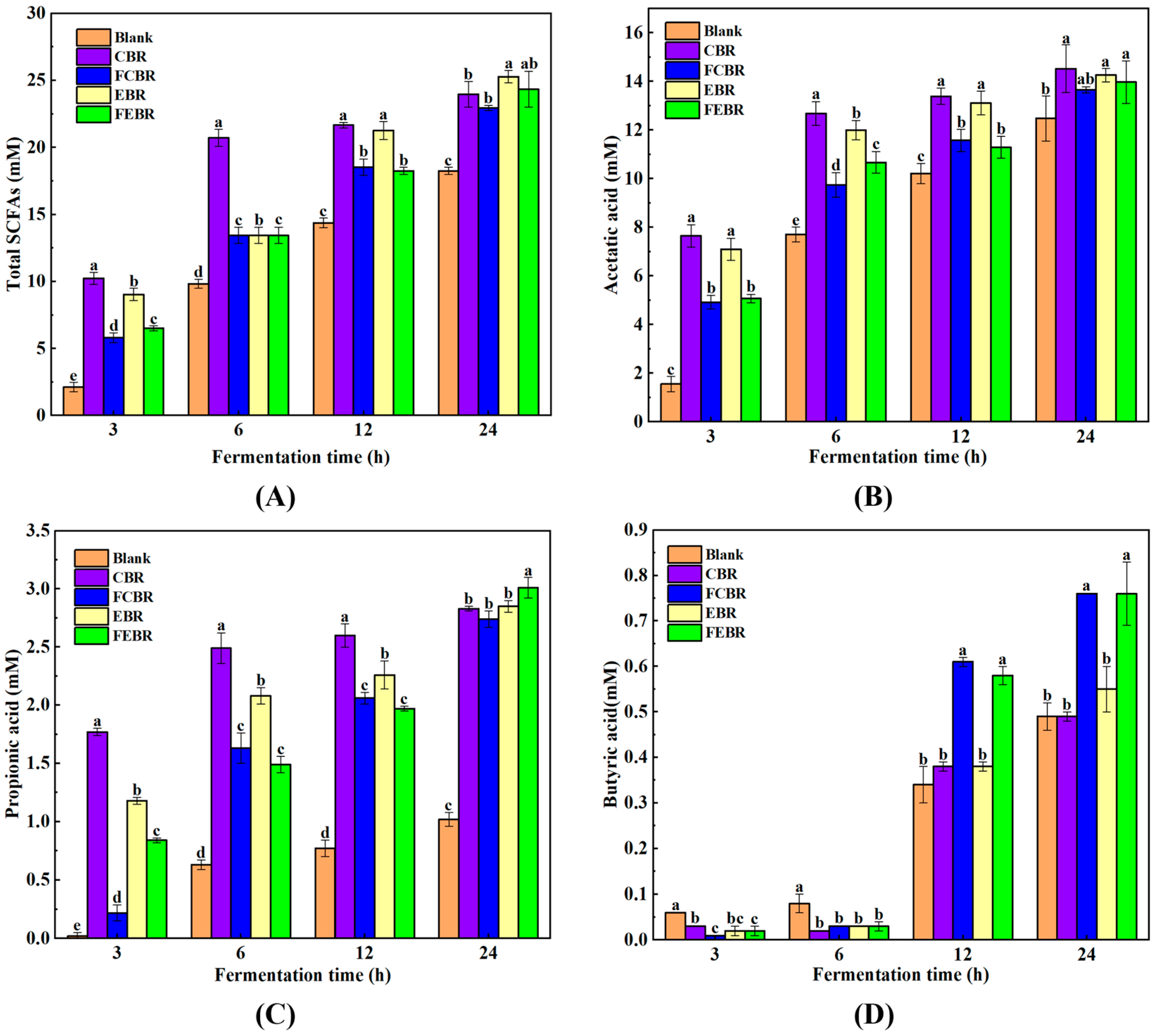

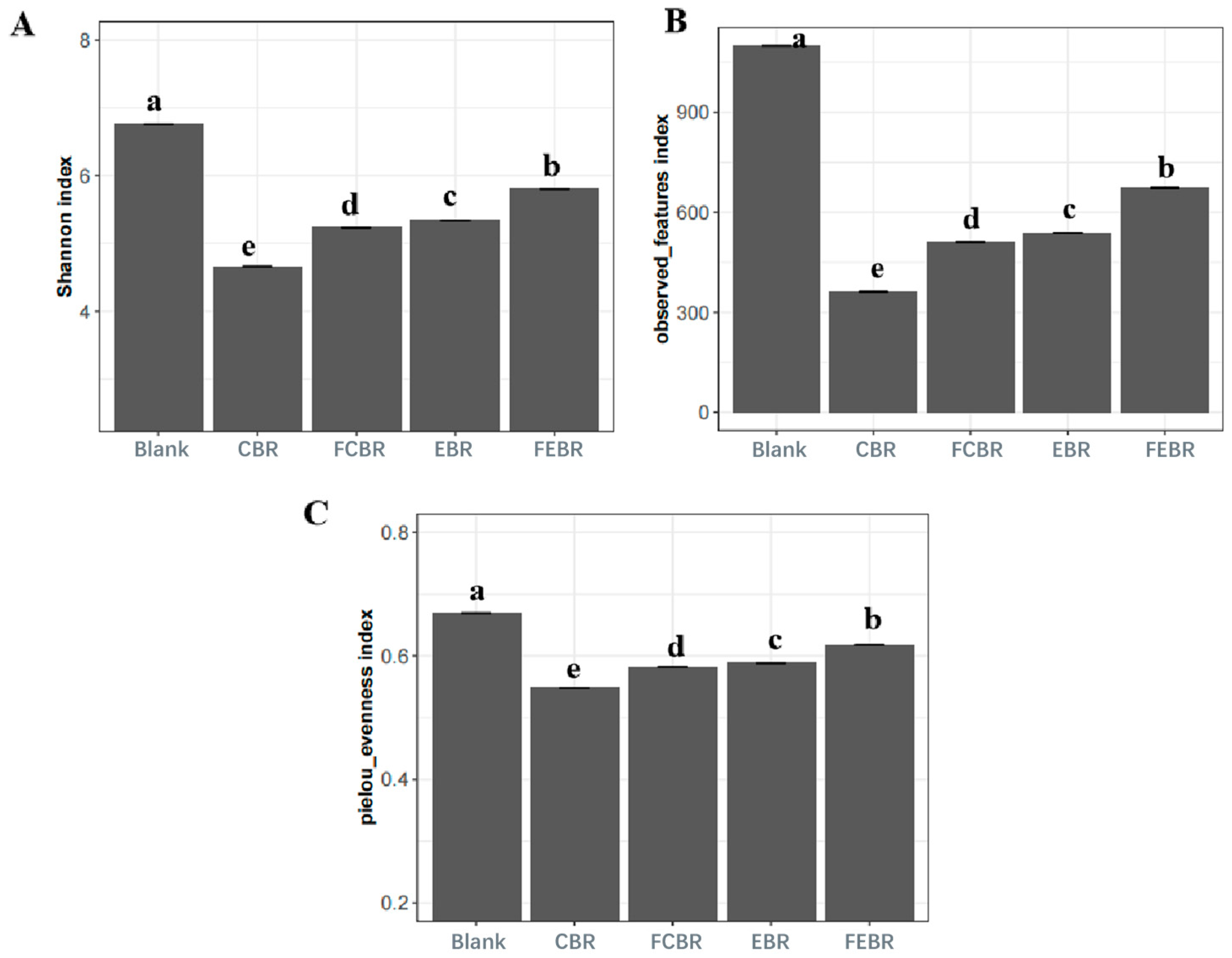

3.2. Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice During In Vitro Fecal Fermentation

3.2.1. Gas Production and pH Variation

3.2.2. SCFA Production

3.2.3. Alpha Diversity of Gut Microbiota

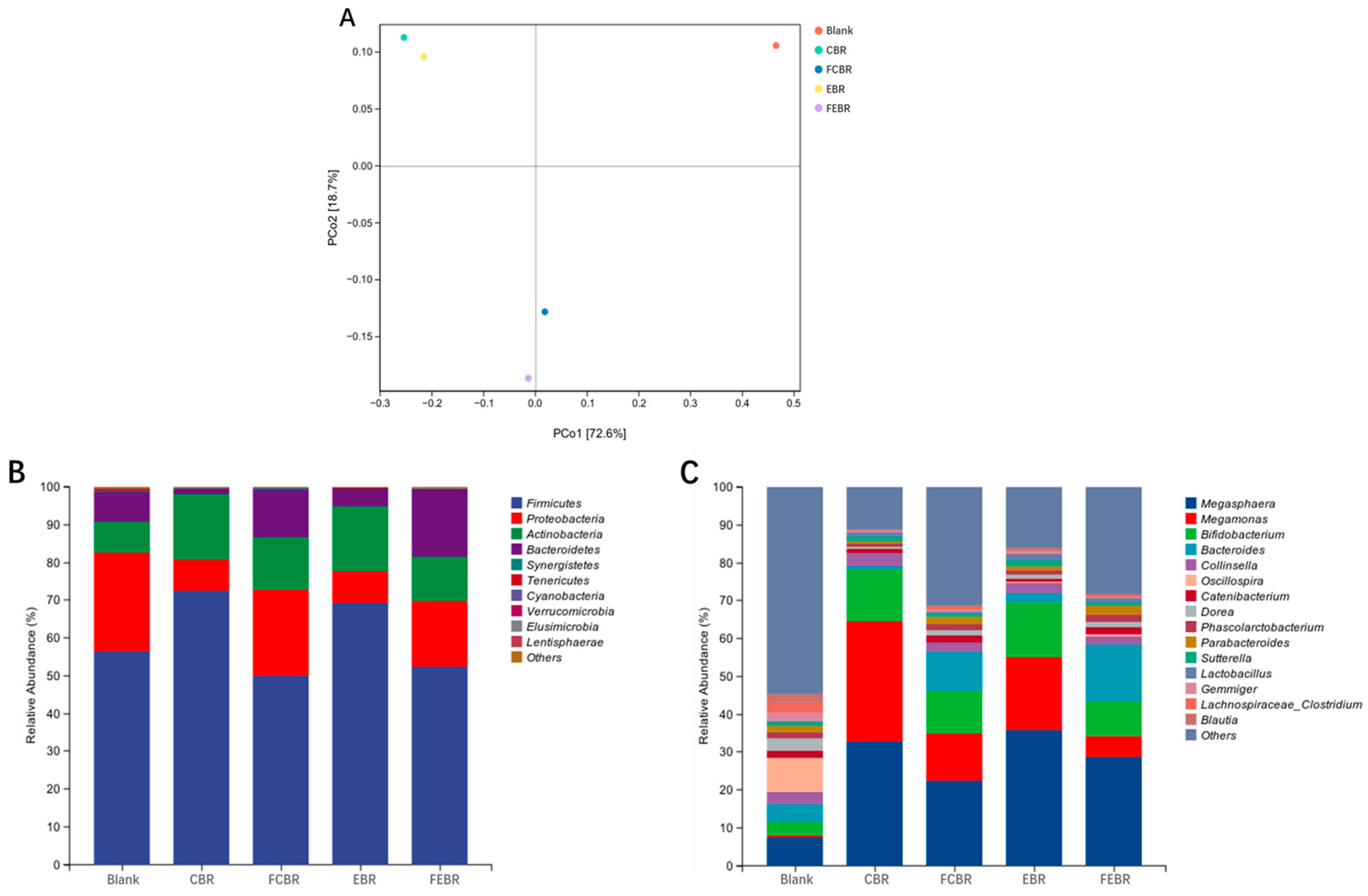

3.2.4. Composition Analysis of Gut Microbiota

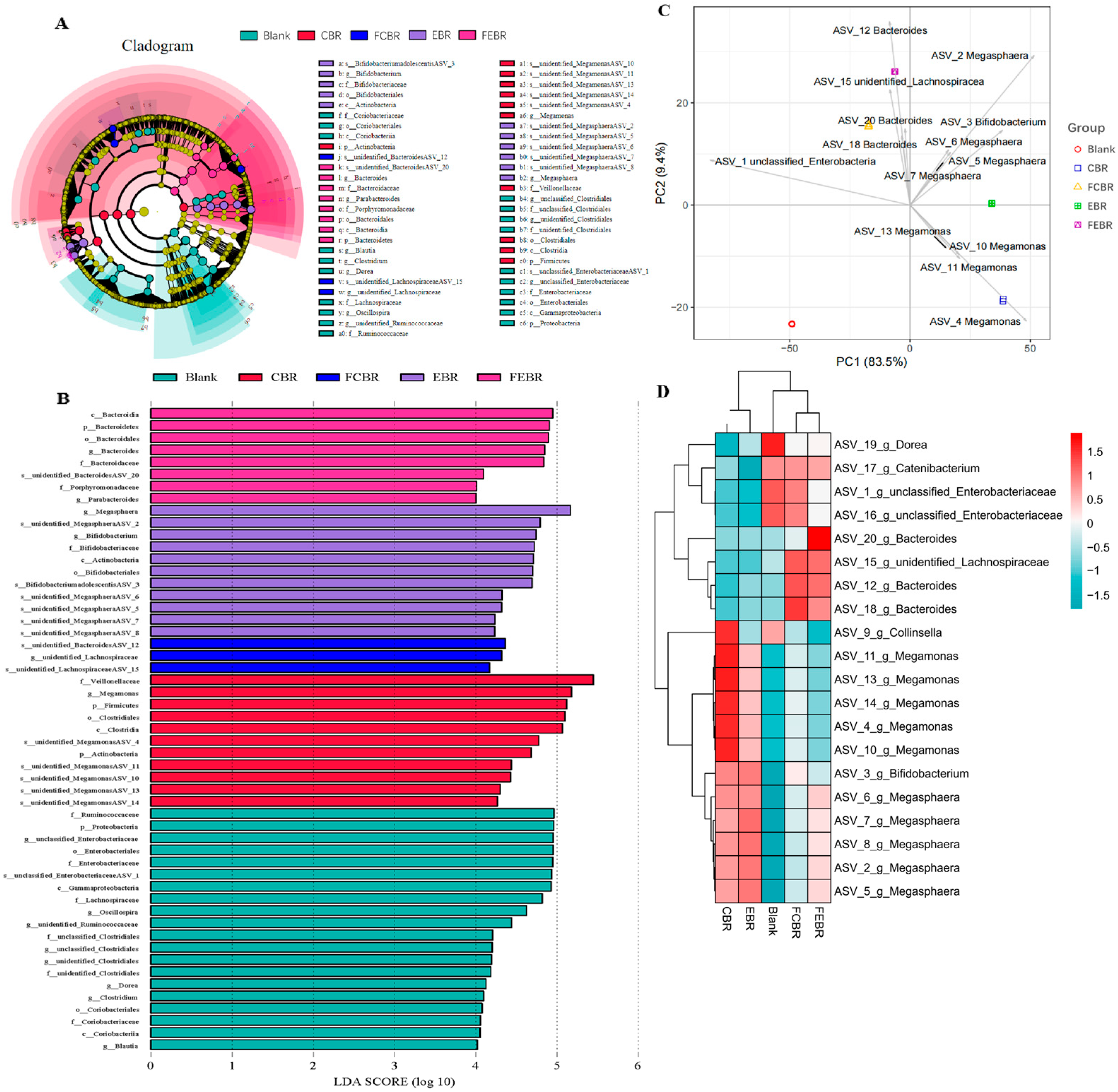

3.2.5. Differential Analysis of the Microbial Community

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ito, V.C.; Lacerda, L.G. Black rice (Oryza sativa L.): A review of its historical aspects, chemical composition, nutritional and functional properties, and applications and processing technologies. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.F.; Xie, Q.T.; Qin, D.D.; He, Y.; Yuan, H.Y.; Mao, Y.C.; Pan, Z.P.; Li, G.Y.; Xia, X.X. Germination-induced biofortification: Improving nutritional efficacy, physicochemical properties, and in vitro digestibility of black rice flour. Foods 2025, 14, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.L.; Long, Y.; Tan, B.; Li, Q.X.; Dong, Z.Y.; Wan, X.Y. Dietary fiber and polyphenols from whole grains: Effects on the gut and health improvements. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 4682–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.J.; Chen, L.; Zheng, Y.W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.X.; Zeng, Z.C. Improvement of overall quality of black rice by stabilization combined with solid-state fermentation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2025, 99, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.R.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Song, M.D.; Li, M.; Benjakul, S.; Li, Z.B.; Zhao, Q.C. Effects of the ratio of alaskan pollock surimi to wheat flour on the quality characteristics and protein interactions of innovative extruded surimi-flour blends. Foods 2025, 14, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandino, M.; Bresciani, A.; Loscalzo, M.; Vanara, F.; Marti, A. Extruded snacks from pigmented rice: Phenolic profile and physical properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 103, 103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Liang, H.X.; Hu, Z.Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.J.; Zhuang, K.; Ding, W.P.; Shen, Q. Evaluation of flavor properties in rice bran by solid-state fermentation with yeast. Food Chem. X 2025, 28, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, S.T. Solid-state fermentation of black rice bran with Aspergillus awamori and Aspergillus oryzae: Effects on phenolic acid composition and antioxidant activity of bran extracts. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Van Haute, M.J.; Rose, D.J. Processing has differential effects on microbiota-accessible carbohydrates in whole grains during in vitro fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2020, 86, e01705-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.T.; Xie, C.Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Tian, Z.Y.; Feng, J.N.; Shen, X.Y.; Li, H.Q.; Chang, S.M.; Zhao, C.H.; et al. Characterization and the cholesterol-lowering effect of dietary fiber from fermented black rice (Oryza sativa L.). Food Funct. 2023, 14, 6128–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraithong, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Suwanangul, S.; Sangsawad, R.; Theppawong, A.; Bunyameen, N. A comprehensive review of the impact of anthocyanins from purple/black Rice on starch and protein digestibility, gut microbiota modulation, and their applications in food products. Food Chem. 2025, 473, 143007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, M.; Wang, R.S.; Lin, S.Y.; Shi, Y.K.; Xu, X.H.; Qin, T.Y.; Xiao, J.H.; Li, D.M.; et al. Impact of enzymatic extruded brown rice flour on wheat-based dough properties and bread quality. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Liu, X.Z.; Liu, C.M.; Wu, J.Y.; Huang, H.X.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, Z.C. Structural characteristics of cooked black rice influenced by different stabilization treatments and their effect mechanism on the in vitro digestibility. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 16, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T.; Long, W.M.; Zhang, C.H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L.P.; Hamaker, B.R. Fiber-utilizing capacity varies in Prevotella-versus Bacteroides-dominated gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; He, Y.X.; Wang, H.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhong, Y.D.; Hu, X.T.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y.; Hu, J.L. Impact of eight extruded starchy whole grains on glycemic regulation and fecal microbiota modulation. Food Hydrocolloid 2025, 160, 110756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Hou, Y.Q.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.X.; Luo, S.J.; Liu, C.M.; Zhang, G.W.; Chen, T.T. Strategic alteration of arabinoxylan feruloylation enables selective shaping of the human gut microbiota. Food Hydrocolloid 2025, 160, 110818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.J.; Hou, Y.Q.; Xie, L.; Zhang, H.B.; Liu, C.M.; Chen, T.T. Effects of microwave on the potential microbiota modulating effects of agro-industrial by-product fibers among different individuals. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 178, 114621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.F.; Zhang, B.; Xia, Y.H.; Li, H.Y.; Shi, X.P.; Wang, J.W.; Deng, Z.Y. Bioaccessibility and transformation pathways of phenolic compounds in processed mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and faecal fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 60, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, H.Y.; Deng, Z.Y.; Tsao, R. A review on insoluble-bound phenolics in plant-based food matrix and their contribution to human health with future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.F.; Khan, S.A.; Chi, J.W.; Wei, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M.W. Different effects of extrusion on the phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity in milled fractions of brown rice. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 88, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.R.; Tian, X.F.; Bei, Q.; Wu, Z.Q. Enhancing three phenolic fractions of oats (Avena sativa L.) and their antioxidant activities by solid-state fermentation with Monascus anka and Bacillus subtilis. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 93, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Riar, C.S.; Jindal, N. Effect of extraction methods and simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on phenolic compound profile, bioaccessibility, and antioxidant activity of Meghalayan cherry (Prunus nepalensis) pomace extracts. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velazquez, O.A.; Mulero, M.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mondor, M.; Arcand, Y.; Hernández-Alvarez, A.J. In vitro gastrointestinal digestion impact on stability, bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of polyphenols from wild and commercial blackberries (Rubus spp.). Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7358–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Szymanowska, U.; Zlotek, U.; Zielinska, E. Digestion and bioavailability of bioactive phytochemicals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuholm, S.; Nielsen, D.S.; Iversen, K.N.; Suhr, J.; Westermann, P.; Krych, L.; Andersen, J.R.; Kristensen, M. Whole-grain rye and wheat affect some markers of gut health without altering the fecal microbiota in healthy overweight adults: A 6-week randomized trial. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Fu, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, G.; Li, C. Phytochemical profile, bioactivity and prebiotic potential of bound polyphenols released from Rosa roxburghii fruit pomace dietary fiber during in vitro digestion and fermentation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 8880–8891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.Q.; Luo, S.J.; Li, Z.X.; Zhang, H.B.; Chen, T.T.; Liu, C.M. Extrusion treatment of rice bran insoluble fiber generates specific niches favorable for Bacteroides during in vitro fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.S.; Zhang, J.N.; Chen, K.N.; Xiao, C.X.; Fan, L.N.; Zhang, B.Z.; Ren, J.L.; Fang, B.S. An in vitro fermentation study on the effects of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on human intestinal microbiota from fecal microbiota transplantation donors. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 53, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Wichienchot, S.; He, X.W.; Fu, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, B. In vitro colonic fermentation of dietary fibers: Fermentation rate, short-chain fatty acid production and changes in microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Q.; Hou, A.X.; Tang, J.J.; Zhong, A.A.; Li, K.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.J. Antioxidant activity of Vitis davidii foex seed and its effects on gut microbiota during colonic fermentation after in vitro simulated digestion. Foods 2022, 11, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, H.X.; Zhou, H.Z.; Shang, H.M. Ultrasonic enzyme-assisted extraction of comfrey (Symphytum officinale L.) polysaccharides and their digestion and fermentation behaviors in vitro. Process Biochem. 2022, 112, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Marcos, J.A.; Perez-Jimenez, F.; Camargo, A. The role of diet and intestinal microbiota in the development of metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 70, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.; He, Y.X.; Zhao, J.T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, C.H.; He, H.J.; Wu, Q.Y.; Hu, M.W.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y.; et al. Effects of boiling and steaming process on dietary fiber components and in vitro fermentation characteristics of 9 kinds of whole grains. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.B.; Yan, X.Y.; Yan, X.D.; Wu, Q.R.; Wu, J.Y.; Liu, C.M.; Xiong, B.S.; Chen, T.T.; Luo, S.J. Impact of flour particle size on digestibility and gut microbiota modulation in brown rice noodles: Balancing cell wall disruption and starch damage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stage | Phenolic Acid | Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBR | FCBR | EBR | FEBR | ||

| Intestinal | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 662.56 ± 22.64 a | 670.82 ± 15.16 a | 658.21 ± 16.61 a | 664.40 ± 23.01 a |

| vanillic acid | 115.71 ± 2.76 c | 126.77 ± 2.10 b | 123.38 ± 2.55 b | 144.79 ± 5.54 a | |

| caffeic acid | 75.17 ± 0.38 c | 83.37 ± 0.36 a | 76.72 ± 0.70 b | 71.76 ± 0.52 d | |

| syringic acid | 21.75 ± 0.99 b | 20.77 ± 0.09 c | 24.06 ± 0.32 a | 24.32 ± 0.12 a | |

| trans-p-coumaric acid | 2.10 ± 0.12 c | 2.09 ± 0.12 c | 4.95 ± 0.16 a | 4.05 ± 0.52 b | |

| trans-ferulic acid | 38.96 ± 0.13 c | 38.37 ± 0.28 c | 66.60 ± 0.63 a | 45.45 ± 0.65 b | |

| trans-sinapic acid | 39.05 ± 0.34 c | 46.23 ± 2.45 b | 39.81 ± 0.99 c | 49.22 ± 1.19 a | |

| total | 955.31 ± 22.40 b | 988.43 ± 15.87 ab | 993.72 ± 18.68 ab | 1003.99 ± 29.20 a | |

| Dialysate | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 27.79 ± 1.73 a | 29.12 ± 2.25 a | 28.82 ± 1.28 a | 30.83 ± 1.28 a |

| vanillic acid | 5.18 ± 0.27 a | 5.35 ± 0.08 a | 5.38 ± 0.44 a | 5.81 ± 0.66 a | |

| caffeic acid | 5.33 ± 0.12 c | 6.43 ± 0.08 b | 6.84 ± 0.26 a | 6.34 ± 0.25 b | |

| syringic acid | 1.00 ± 0.03 a | 0.78 ± 0.03 b | 0.75 ± 0.03 b | 0.98 ± 0.03 a | |

| trans-p-coumaric acid | 0.28 ± 0.01 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 c | 0.20 ± 0.03 b | 0.23 ± 0.01 b | |

| trans-ferulic acid | 1.85 ± 0.05 b | 1.41 ± 0.04 c | 1.36 ± 0.04 c | 3.01 ± 0.14 a | |

| trans-sinapic acid | 1.65 ± 0.01 b | 1.54 ± 0.02 c | 1.49 ± 0.02 c | 2.00 ± 0.05 a | |

| total | 43.07 ± 2.20 b | 44.78 ± 2.47 b | 44.85 ± 1.93 b | 49.20 ± 2.37 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bo, C.; Gong, E.; Zou, L.; Zhong, Y.; Chu, J.; Wu, J.; He, F.; Zeng, Z. Improvement of Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice by Extrusion Combined with Solid-State Fermentation. Foods 2026, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010032

Bo C, Gong E, Zou L, Zhong Y, Chu J, Wu J, He F, Zeng Z. Improvement of Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice by Extrusion Combined with Solid-State Fermentation. Foods. 2026; 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleBo, Chunyan, Ersheng Gong, Liqiang Zou, Yejun Zhong, Jinshen Chu, Jianyong Wu, Fangqing He, and Zicong Zeng. 2026. "Improvement of Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice by Extrusion Combined with Solid-State Fermentation" Foods 15, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010032

APA StyleBo, C., Gong, E., Zou, L., Zhong, Y., Chu, J., Wu, J., He, F., & Zeng, Z. (2026). Improvement of Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Gut Microbiota Modulation Potential of Black Rice by Extrusion Combined with Solid-State Fermentation. Foods, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010032