Mechanisms and Critical Thresholds of Cold Storage Duration-Modulated Postharvest Quality Deterioration in Litchi Fruit During Ambient Shelf Life

Abstract

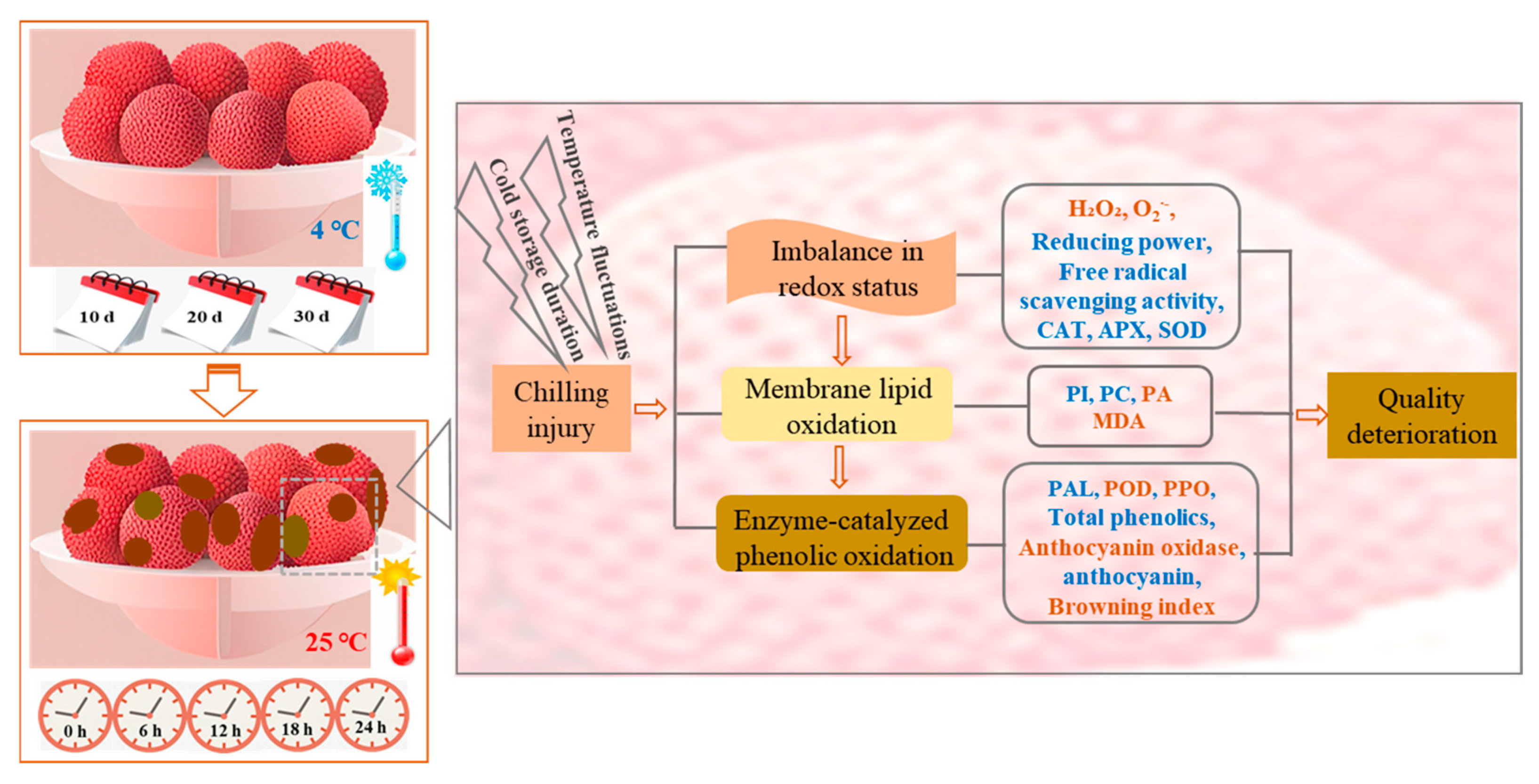

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. Assessment of Pericarp Browning Index and Moisture Content

2.3. Determinations of Content of Anthocyanins, Total Phenolics, Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2), and Malondialdehyde (MDA)

2.4. Determinations of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), and Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) Activities

2.5. Evaluations of Reducing Power and Free Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Determination of Activities of PPO, POD, PAL, and Anthocyanase

2.7. Determination of Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Phosphatidylinositol (PI), and Phosphatidic Acid (PA) Content

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pericarp Browning, MDA Content, H2O2 Content, O2·− Production Rate

3.2. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, Reducing Power, and Free Radical Scavenging Activity

3.3. Contents of PC, PI, and PA

3.4. Contents of Anthocyanins, Total Phenolics, and Activities of Anthocyanase, PPO, POD, and PAL

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| PPO | Polyphenol oxidase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| PAL | Phenylalanine ammonia lyase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PI | Phosphatidylinositol |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PA | Phosphatidic acid |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| IP3 | Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

References

- Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. Nutrient components, health benefits, and safety of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.): A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2139–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X.; Jiang, G. Phytosulfokine treatment delays browning of litchi pericarps during storage at room temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, L.; You, Y.; Li, Y.; Duan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Joyce, D.C.; Ashraf, M.; Lu, W. Cold storage duration affects litchi fruit quality, membrane permeability, enzyme activities and energy charge during shelf time at ambient temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 60, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Qu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, X.; Yang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, Y. Comparative transcriptome and metabolome provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms of accelerated senescence in litchi fruit after cold storage. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, R.R.; Caleb, O.J.; Ngcobo, M.E.K. Effects of packaging and duration on quality of minimally processed and unpitted litchi cv. ‘Mauritius’ under low storage temperature. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Eo, H.; Kim, C.; Stewart, J.; Lee, U.; Lee, J. Physiological disorders in cold-stored ‘Autumn Sense’ hardy kiwifruit depend on the storage temperature and the modulation of targeted metabolites. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, J. Delay of pericarp browning by chondroitin sulfate attributes of enhancing antioxidant activity and membrane integrity in litchi fruit after harvest. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 227, 113612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Lin, H.; Jiang, Y. Effect of pure oxygen atmosphere on antioxidant enzyme and antioxidant activity of harvested litchi fruit during storage. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, F.; Xie, L.; Dai, T.; Jiang, Y. Gallic acid reduces pericarp browning of litchi fruit during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shi, D.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, H.; Jiang, Y. Sodium para-aminosalicylate delays pericarp browning of litchi fruit by inhibiting ROS-mediated senescence during postharvest storage. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhou, C.; Fan, J.; Shanklin, J.; Xu, C. Mechanisms and functions of membrane lipid remodeling in plants. Plant J. 2021, 107, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, F. Identification and stability evaluation of polyphenol oxidase substrates of pineapple fruit. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy Choudhury, S.; Pandey, S. Phosphatidic acid binding inhibits RGS1 activity to affect specific signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2017, 90, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, Z.; Song, L.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Inhibition of postharvest soft rot in Chinese flowering cabbage by propyl gallate. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 231, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z. Trehalose delays postharvest browning of litchi fruit by regulating antioxidant capacity, anthocyanin synthesis and energy status. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Asaeda, T.; Fukahori, K.; Imamura, F.; Nohara, A.; Matsubayashi, M. Hydrogen peroxide measurement can be used to monitor plant oxidative stress rapidly using modified ferrous oxidation xylenol orange and titanium sulfate assay correlation. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2023, 14, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Shao, C.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. Combination of sodium nitroprusside and controlled atmosphere maintains postharvest quality of chestnuts through enhancement of antioxidant capacity. Foods 2024, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Gou, M.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, X.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yang, J. Application of Ferulic Acid to Alleviate Chilling Injury of Banana Fruit by Regulating Redox, Phenylpropanoid, and Energy Metabolism. Food Front. 2025, 6, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huber, D.J.; Hu, M.; Jiang, G.; Gao, Z.; Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Delay of postharvest browning in litchi fruit by melatonin via the enhancing of antioxidative processes and oxidation repair. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7475–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Xi, P.; Lin, Z.; Huang, J.; Lu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Qiao, F. Efficacy and potential mechanisms of benzothiadiazole inhibition on postharvest litchi downy blight. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pang, X.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, Y. Role of anthocyanin degradation in litchi pericarp browning. Food Chem. 2001, 75, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Shi, J.; Lin, Y. Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Pat.) Griff. & Maubl.-induced disease development and pericarp browning of harvested longan fruit in association with membrane lipids metabolism. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Zuo, M.; Zhu, W.-Y.; Zuo, J.-H.; Lü, E.-L.; Yang, X.-T. A comprehensive review of cold chain logistics for fresh agricultural products: Current status, challenges, and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 109, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xu, C.; Guo, C.; Zhang, X. Sub-zero temperature preservation of fruits and vegetables: A review. J. Food Eng. 2020, 275, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bao, Y.; Meng, L.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses provide new insights into the regulatory mechanisms of accelerated senescence of litchi fruit in response to strigolactones. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Marenkova, T.V.; Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M. Antioxidants of non-enzymatic nature: Their function in higher plant cells and the ways of boosting their biosynthesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Qu, H.; Duan, X.; Jiang, Y. Role of hydrogen peroxide receptors in endocarp browning of postharvest longan fruit. Food Front. 2024, 5, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, G.; Heinonen, M. LC–MS investigations on interactions between isolated β-lactoglobulin peptides and lipid oxidation product malondialdehyde. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, D.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Romero, R.; Prasad, R.; Singh, J. Antioxidant enzymes regulation in plants in reference to reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Plant Gene 2019, 19, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.; Song, C. Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Bi, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Reduction of Membrane Lipid Metabolism in Postharvest Hami Melon Fruits by n-Butanol to Mitigate Chilling Injury and the Cloning of Phospholipase D-β Gene. Foods 2023, 12, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bhatnagar, N.; Pandey, A.; Pandey, G.K. Plant phospholipase C family: Regulation and functional role in lipid signaling. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yücetepe, M.; Özaslan, Z.T.; Karakuş, M.Ş.; Akalan, M.; Karaaslan, A.; Karaaslan, M.; Başyiğit, B. Unveiling the multifaceted world of anthocyanins: Biosynthesis pathway, natural sources, extraction methods, copigmentation, encapsulation techniques, and future food applications. Food Res. Int. 2024, 187, 114437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yin, F.; Dek, M.S.P.; Liao, L.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cai, W.; Huang, L.; Shuai, L. Methyl jasmonate delays the browning of litchi pericarp by activating the phenylpropanoid metabolism during cold storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, V.; Gatica, M.; Uribe, E.; Román, J. In silico analysis of the mecular interaction between anthocyanase, peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase with anthocyanins found in cranberries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, M.; Gao, Z.; An, F.; Li, M.; Jiang, Y. Low-temperature conditioning induces chilling tolerance in stored mango fruit. Food Chem. 2017, 219, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.; Acıkalın, R.; Ozturk, B.; Aglar, E.; Kaiser, C. Combined effects of Aloe vera gel and modified atmosphere packaging treatments on fruit quality traits and bioactive compounds of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) fruit during cold storage and shelf life. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 187, 111855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ye, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, Z.; Su, M.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. 1-MCP regulates taste development in cold-stored peach fruit through modulation of sugar, organic acid, and polyphenolic metabolism. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 225, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Xiang, X. Cuticular wax metabolism responses to atmospheric water stress on the exocarp surface of litchi fruit after harvest. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Song, L.; Li, L.; Liao, Y.; Du, H.; Li, F. Mechanisms and Critical Thresholds of Cold Storage Duration-Modulated Postharvest Quality Deterioration in Litchi Fruit During Ambient Shelf Life. Foods 2026, 15, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010176

Liu H, Xu Z, Song L, Li L, Liao Y, Du H, Li F. Mechanisms and Critical Thresholds of Cold Storage Duration-Modulated Postharvest Quality Deterioration in Litchi Fruit During Ambient Shelf Life. Foods. 2026; 15(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Hai, Zhili Xu, Longlong Song, Lilang Li, Yan Liao, Hui Du, and Fengjun Li. 2026. "Mechanisms and Critical Thresholds of Cold Storage Duration-Modulated Postharvest Quality Deterioration in Litchi Fruit During Ambient Shelf Life" Foods 15, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010176

APA StyleLiu, H., Xu, Z., Song, L., Li, L., Liao, Y., Du, H., & Li, F. (2026). Mechanisms and Critical Thresholds of Cold Storage Duration-Modulated Postharvest Quality Deterioration in Litchi Fruit During Ambient Shelf Life. Foods, 15(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010176