Isolation of a New Acetobacter pasteurianus Strain from Spontaneous Wine Fermentations and Evaluation of Its Bacterial Cellulose Production Capacity on Natural Agrifood Sidestreams

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Raw Materials

2.3. Isolation of AAB

2.4. Identification of AAB

2.4.1. DNA Extraction

2.4.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.4.3. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (AGE)

2.4.4. DNA Sequencing

2.5. Optimization of BC Production

2.6. Analytical Methods

2.6.1. Microbiological Analysis of the Isolated Strain

2.6.2. Determination of Sugars and Organic Acids

2.6.3. Determination of Vitamin C and Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.6.4. Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

2.6.5. Physicochemical Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity

2.6.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Isolated Strain

3.2. Molecular Identification of the New Strain

3.3. Optimization of BC Production and Model Validation

3.4. Composition of the Substrates and Wastewaters of BC Production

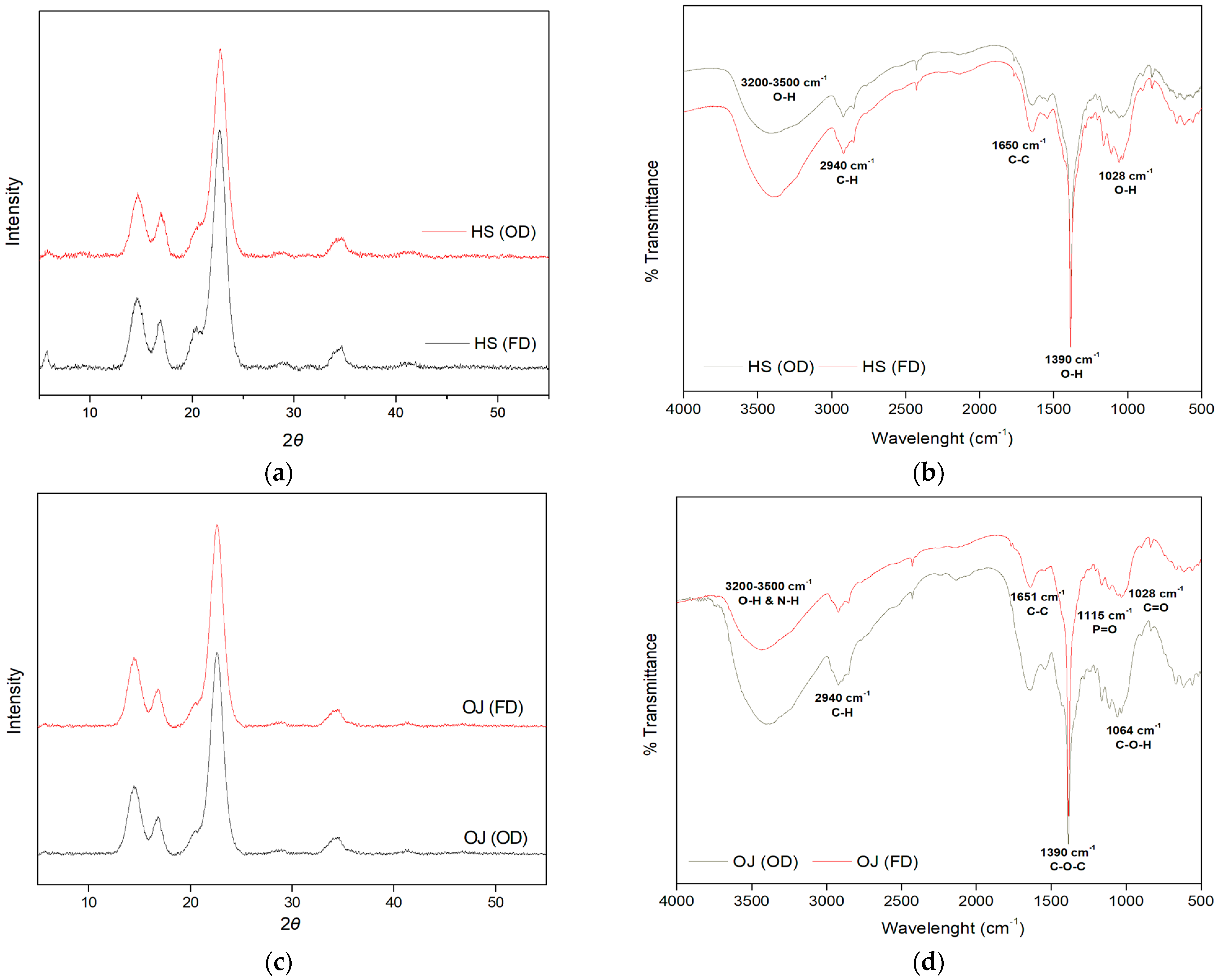

3.5. Physicochemical Characterization of BC

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Bacterial Cellulose |

| SRE | Substandard Raisin Extracts |

| OJ | Orange Juice |

| GTE | Green Tea Extract |

| HS | Hestrin–Schramm Medium |

| OD | Oven-Dried |

| FD | Freeze-Dried |

| AAB | Acetic Acid Bacteria |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| GY | Glucose–Yeast Extract Medium |

| GYC | GY–CaCO3 Medium |

| EYC | Ethanol–Yeast Extract–CaCO3 Medium |

| DHA | Dihydroxyacetone |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| AGE | Agarose Gel Electrophoresis |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| TAE | Tris-Acetate-EDTA |

| Etbr | Ethidium Bromide |

| TPC | Total Phenolic Content |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| FT-IR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| SA | Surface Area |

| APD | Average Pore Diameter |

| CPV | Cumulative Pore Volume |

| CI | Crystallinity Index |

| CS | Crystallite Size |

References

- Gorgieva, S.; Trček, J. Bacterial cellulose: Production, modification and perspectives in biomedical applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, L.; Corcuera, M.Á.; Gabilondo, N.; Eceiza, A.; Retegi, A. A review of bacterial cellulose: Sustainable production from agricultural waste and applications in various fields. Cellulose 2021, 28, 8229–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, V.; Bekatorou, A.; Brinias, V.; Michalopoulou, P.; Dimopoulos, C.; Zafeiropoulos, J.; Petsi, T.; Koutinas, A.A. Optimization of bacterial cellulose production by Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans in synthetic media and agrifood side streams supplemented with organic acids and vitamins. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 398, 130511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupașcu, R.E.; Ghica, M.V.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.; Popa, L.; Velescu, B.Ș.; Arsene, A.L. An overview regarding microbial aspects of production and applications of bacterial cellulose. Materials 2022, 15, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Liu, Z.; Shen, R.; Chen, S.; Yang, X. Bacterial cellulose in food industry: Current research and future prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekatorou, A.; Plioni, I.; Sparou, K.; Maroutsiou, R.; Tsafrakidou, P.; Petsi, T.; Kordouli, E. Bacterial cellulose production using the Corinthian currant finishing side-stream and cheese whey: Process optimization and textural characterization. Foods 2019, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsou, V.; De Melo, E.M.; Tsouko, E.; Ladakis, D.; Maragkoudaki, S.; Koutinas, A.A.; Matharu, A.S. Synthesis and characterization of bacterial cellulose from citrus-based sustainable resources. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10365–10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, I.D.; Maciel, G.M.; Oliveira, A.L.; Miorim, A.J.; Fontana, J.D.; Ribeiro, V.R.; Haminiuk, C.W. Hybrid bacterial cellulose-collagen membranes production in culture media enriched with antioxidant compounds from plant extracts. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.U.; Ullah, M.W.; Khan, S.; Shah, N.; Park, J.K. Strategies for cost-effective and enhanced production of bacterial cellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleenwerck, I.; De Vos, P. Polyphasic taxonomy of acetic acid bacteria: An overview of the currently applied methodology. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, X. Characterization of bacterial cellulose produced by Acetobacter pasteurianus MGC-N8819 utilizing lotus rhizome. LWT 2022, 165, 113763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozali, M.; Meliana, Y.; Chalid, M. Synthesis and characterization of bacterial cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum using liquid tapioca waste. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 2131–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.J.; Ida, E.I.; Spinosa, W.A. Nutritional supplementation with amino acids on bacterial cellulose production by Komagataeibacter intermedius: Effect analysis and application of response surface methodology. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 5017–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, V.; Salvanou, A.; Bekatorou, A.; Petsi, T.; Dima, A.; Giannakas, A.E.; Kanellaki, M. Production and in situ modification of bacterial cellulose gels in raisin side-stream extracts using nanostructures carrying thyme oil: Their physicochemical/textural characterization and use as antimicrobial cheese packaging. Gels 2023, 9, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis: OIV-MA-AS4-01 Microbiological Analysis of Wines and Musts—Detection, Differentiation and Counting of Micro-Organisms; OIV: Dijon, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oiv.int/node/2099/download/pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Aydin, Y.A.; Aksoy, N.D. Utilization of vinegar for isolation of cellulose producing acetic acid bacteria. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1247, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., KG. NucleoSpin® Tissue—Genomic DNA from Tissue: User Manual, Rev. 21, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany, 2024. Available online: https://www.mn-net.com/media/pdf/5b/d0/d9/Instruction-NucleoSpin-Tissue.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Ruiz, A.; Poblet, M.; Mas, A.; Guillamón, J.M. Identification of acetic acid bacteria by RFLP of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA and 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 1981–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Nucleotide BLAST: Search Nucleotide Databases Using a Nucleotide Query. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Guillamon, J.; Mas, A. Chapter 2: Acetic Acid Bacteria. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine; Konig, H., Unden, G., Frohlich, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Yukphan, P.; Lan Vu, H.T.; Muramatsu, Y.; Ochaikul, D.; Tanasupawat, S.; Nakagawa, Y. Description of Komagataeibacter gen. nov., with proposals of new combinations (Acetobacteraceae). J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plioni, I.; Bekatorou, A.; Mallouchos, A.; Kandylis, P.; Chiou, A.; Panagopoulou, E.A.; Dede, V.; Styliara, P. Corinthian currants finishing side-stream: Chemical characterization, volatilome, and valorisation through wine and baker’s yeast production-technoeconomic evaluation. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, R.J.; Borges, M.F.; Rosa, M.F.; Castro-Gómez, R.J.H.; Spinosa, W.A. Acetic acid bacteria in the food industry: Systematics, characteristics and applications. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesenberg-Smith, K.A.; Pessarakli, M.M.; Wolk, D.M. Assessment of DNA yield and purity: An overlooked detail of PCR troubleshooting. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2012, 34, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gullo, M.; Chen, F.; Giudici, P. Diversity of Acetobacter pasteurianus strains isolated from solid-state fermentation of cereal vinegars. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 60, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Jia, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L. Effect of organic acids on bacterial cellulose produced by Acetobacter xylinum. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 5, 1–6. Available online: https://www.rroij.com/open-access/effect-of-organic-acids-on-bacterial-cellulose-produced-byacetobacter-xylinum-.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Keshk, S.M. Vitamin C enhances bacterial cellulose production in Gluconacetobacter xylinus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 99, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozala, A.F.; de Lencastre-Novaes, L.C.; Lopes, A.M.; de Carvalho Santos-Ebinuma, V.; Mazzola, P.G.; Pessoa, A.; Grotto, D.; Gerenutti, M.; Chaud, M.V. Bacterial nanocellulose production and application: A 10-year overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ramírez, C.; Castro, M.; Osorio, M.; Torres-Taborda, M.; Gómez, B.; Zuluaga, R.; Gañán, P. Effect of different carbon sources on bacterial cellulose production and structure using Komagataeibacter medellinensis. Materials 2017, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, D.K.; Bansal, V.; Mehta, D.; Sangwan, R.S.; Yadav, S.K. Efficient and economic process for the pro-duction of bacterial cellulose from isolated strain of Acetobacter pasteurianus of RSV-4 bacterium. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 275, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Song, J.E.; Kim, Y.H. Utilization of plant-based waste substrates for bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter pasteurianus. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 185, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, D.K.; Sandhu, P.P.; Jadaun, J.; Sangwan, R.S.; Yadav, S.K. Sustainable process for the production of cellulose by an Acetobacter pasteurianus RSV-4 (MTCC 25117) on whey medium. Cellulose 2020, 28, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo-Tayo, B.; Akintunde, M.; Sanusi, J. Effect of different fruit juice media on bacterial cellulose production by Acinetobacter sp. BAN1 and Acetobacter pasteurianus PW1. J. Adv. Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.M.; Song, J.E.; Kim, H.R. Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose fabrics by nitrogen sources of tea and carbon sources of sugar. Process Biochem. 2017, 59, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, A.; Naveed, S.; Ramzan, N.; Rafique, M.S.; Imran, M. A green method for the synthesis of copper nanoparticles using L-ascorbic acid. Matéria 2014, 19, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Garza, M.; Guerrero-Medina, A.; González-Sánchez, R.; García-Gómez, C.; Guzmán-Velasco, A.; Báez-González, J.; Márquez-Reyes, J. Production of microbial cellulose films from green tea (Camellia sinensis) kombucha with various carbon sources. Coatings 2020, 10, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, M.S.; Goswami, N.; Sahai, A.; Jain, V.; Mathur, G.; Mathur, A. Effect of media components on cell growth and bacterial cellulose production from Acetobacter aceti MTCC 2623. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Buldum, G.; Mantalaris, A.; Bismarck, A. More than meets the eye in bacterial cellulose: Biosynthesis, bioprocessing, and applications in advanced fiber composites. Macromol. Biosci. 2014, 14, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasen, C.; Sultanova, B.; Wilhelms, T.; Heisig, P.; Kulicke, W.M. Effects of different drying processes on the material properties of bacterial cellulose membranes. Macromol. Symp. 2006, 244, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, M.; Vadivu, K.; Ramesh, S.; Periasamy, V. Corrosion protection of mild steel by a new phosphonate inhibitor system in aqueous solution. Egypt. J. Pet. 2014, 23, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ul-Islam, M.; Ullah, M.W.; Zhu, Y.; Narayanan, K.B.; Han, S.S.; Park, J.K. Fabrication strategies and biomedical applications of three-dimensional bacterial cellulose-based scaffolds: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbial Analysis | New Strain |

|---|---|

| Morphology | Rod |

| Gram strain | Gram-negative |

| Catalase | Positive |

| Oxidase | Negative |

| Acetic acid production | Positive |

| Acetic acid peroxidation | Positive |

| Bacterial cellulose production | Positive |

| Ethanol oxidation | Positive |

| Production of dihydroxyacetone | Negative |

| Strain | DNA Concentration (ng/L) | A260/A280 |

|---|---|---|

| New strain | 44.5 | 1.88 |

| Test | Independent Variables (Substrate Concentration) | Dependent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded Values | Actual Values | BC Yield (g/L) | ||||

| Χ1 (SRE) | Χ2 (GTE) | SRE (%v/v) | GTE (%v/v) | Experimental Value | Predicted Value | |

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 5.01 ± 0.05 | 6.34 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 20 | 0 | 8.91 ± 0.03 | 9.25 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 60 | 2.82 ± 0.01 | 2.32 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 60 | 1.08 ± 0.00 | 0.41 |

| 5 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 8.47 ± 0.04 | 7.64 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 30 | 6.58 ± 0.02 | 7.73 |

| 7 | 0 | −1 | 10 | 0 | 14.5 ± 0.16 | 12.73 |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 60 | 3.99 ± 0.04 | 5.98 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 14.81 ± 0.03 | 12.82 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 15.44 ± 0.02 | 12.82 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 13.88 ± 0.03 | 12.82 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 15.20 ± 0.03 | 12.82 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 14.57 ± 0.01 | 12.82 |

| Parameter | Substrate | Wastewater | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugars (%w/w) | OJ-SRE-GTE | OJ | OJ-SRE-GTE |

| Total | 8.42 ± 0.05 c | 3.14 ± 0.03 d | 1.94 ± 0.02 e |

| Glucose | 3.09 ± 0.04 b | 1.04 ± 0.03 c | 0.81 ± 0.01 d |

| Fructose | 2.62 ± 0.02 b | 1.12 ± 0.03 c | 0.92 ± 0.01 d |

| Sucrose | 2.72 ± 0.02 b | 0.97 ± 0.03 c | 0.22 ± 0.01 d |

| Organic acids (g/L) | |||

| Citric acid | 8.22 ± 0.01 c | 7.23 ± 0.05 d | 5.09 ± 0.06 e |

| Tartaric acid | 0.13 ± 0.02 b | nf | 0.11 ± 0.02 b |

| Mallic acid | 1.21 ± 0.02 b | 1.12 ± 0.02 c | 1.03 ± 0.03 d |

| Vitamin C (mg/100 mL) | 22.0 ± 0.4 c | 22.3 ± 0.9 c | 12.8 ± 0.04 d |

| TPC (mg GAE/L) | 365.0 ± 0.7 d | 232.0 ± 1.1 e | 258.8 ± 0.7 f |

| COD (g/L) | 1.8 ± 0.0 a | 1.8 ± 0.0 b | |

| Parameter | Substrate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | OJ-C | OJ-SRE-GTE | ||||

| OD | FD | OD | FD | OD | FD | |

| SA (m2/g) | 3.9 | 17.4 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 10.5 |

| APD (Å) | 135.2 | 204.7 | 182.5 | 182.5 | 148.8 | 186.9 |

| CPV (cm3/g) | 0.030 | 0.127 | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.066 | 0.088 |

| CI (%) | 68.3 | 67.1 | 65.8 | 64.9 | 63.0 | 63.0 |

| CS (Å) | 66.2 | 69.3 | 66.0 | 70.0 | 69.0 | 69.0 |

| AA (%) | 21.70 ± 0.09 a | 30.07 ± 0.07 b | 43.22 ± 0.25 c | 50.61 ± 0.25 d | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Adamopoulou, V.; Karakovouni, V.; Michalopoulou, P.; Kalligosfyri, P.M.; Dima, A.; Petsi, T.; Kalogianni, D.P.; Bekatorou, A. Isolation of a New Acetobacter pasteurianus Strain from Spontaneous Wine Fermentations and Evaluation of Its Bacterial Cellulose Production Capacity on Natural Agrifood Sidestreams. Foods 2026, 15, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010154

Adamopoulou V, Karakovouni V, Michalopoulou P, Kalligosfyri PM, Dima A, Petsi T, Kalogianni DP, Bekatorou A. Isolation of a New Acetobacter pasteurianus Strain from Spontaneous Wine Fermentations and Evaluation of Its Bacterial Cellulose Production Capacity on Natural Agrifood Sidestreams. Foods. 2026; 15(1):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010154

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamopoulou, Vasiliki, Vasiliki Karakovouni, Panagiota Michalopoulou, Panagiota M. Kalligosfyri, Agapi Dima, Theano Petsi, Despina P. Kalogianni, and Argyro Bekatorou. 2026. "Isolation of a New Acetobacter pasteurianus Strain from Spontaneous Wine Fermentations and Evaluation of Its Bacterial Cellulose Production Capacity on Natural Agrifood Sidestreams" Foods 15, no. 1: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010154

APA StyleAdamopoulou, V., Karakovouni, V., Michalopoulou, P., Kalligosfyri, P. M., Dima, A., Petsi, T., Kalogianni, D. P., & Bekatorou, A. (2026). Isolation of a New Acetobacter pasteurianus Strain from Spontaneous Wine Fermentations and Evaluation of Its Bacterial Cellulose Production Capacity on Natural Agrifood Sidestreams. Foods, 15(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010154