Effects of Palm Oil Nanoparticles in Diverse Physical States on the Properties of Starch Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of PO-Nanoemulsions with Different Melting Points

2.3. Preparation of Starch–PO Films

2.4. Rheology of Film-Forming Solutions

2.5. Color Parameters

2.6. Thickness, Moisture Content, Total Soluble Matter Content and WVP of Starch–PO Films

2.6.1. Thickness

2.6.2. Moisture Content and Total Soluble Matter Content

2.6.3. WVP

2.7. Mechanical Properties of Starch–PO Films

2.8. Structural Characteristics of Starch–PO Films

2.8.1. Microstructure Observation of Starch–PO Films

2.8.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) of Starch–PO Films

2.8.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) of PO and Starch–PO Films

2.9. Thermogravimetry (TG) Analysis of Starch–PO Films

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of PO with Different Melting Points

3.2. Nanoemulsions Properties

3.3. Rheological Properties of Film-Forming Solution

3.4. Optical Properties of Starch–PO Films

3.5. Structural Characteristics of Starch–PO Films

3.5.1. SEM of Starch–PO Films

3.5.2. CLSM of Starch–PO Films

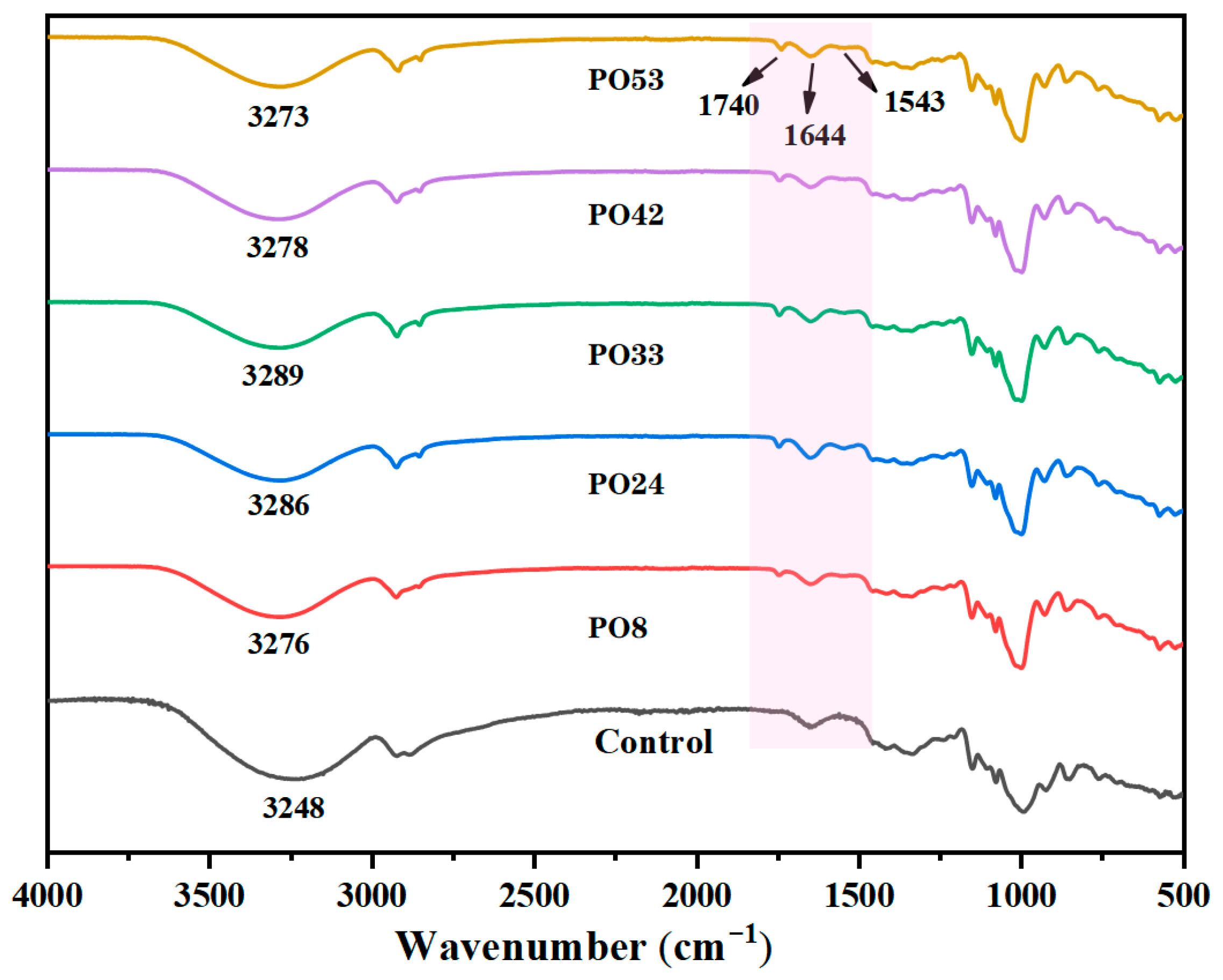

3.5.3. FTIR of Starch–PO Films

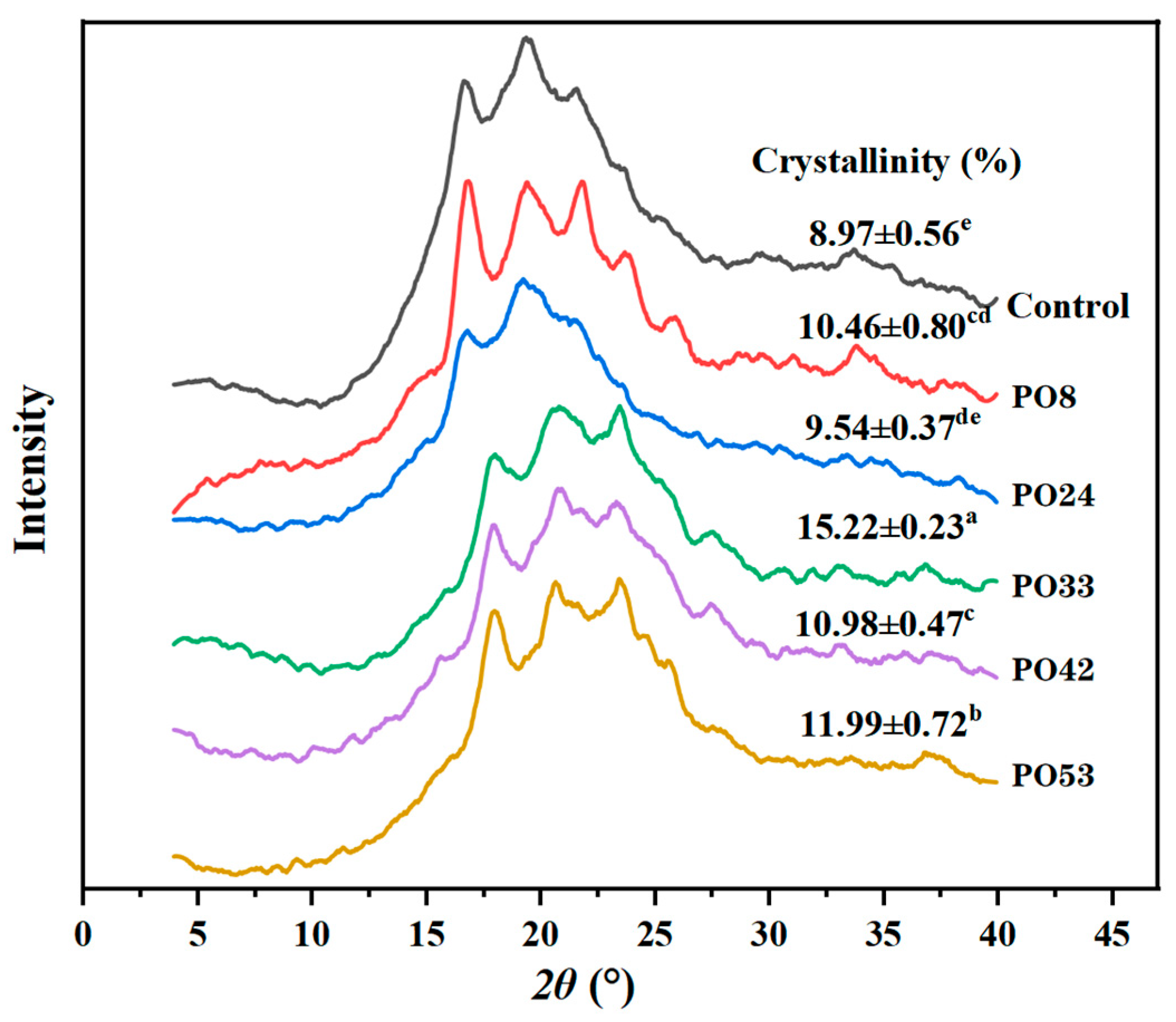

3.5.4. XRD of Starch–PO Films

3.6. Basic Properties of Starch–PO Films

3.6.1. Thickness

3.6.2. WVP

3.6.3. Moisture Content and Total Soluble Matter Content

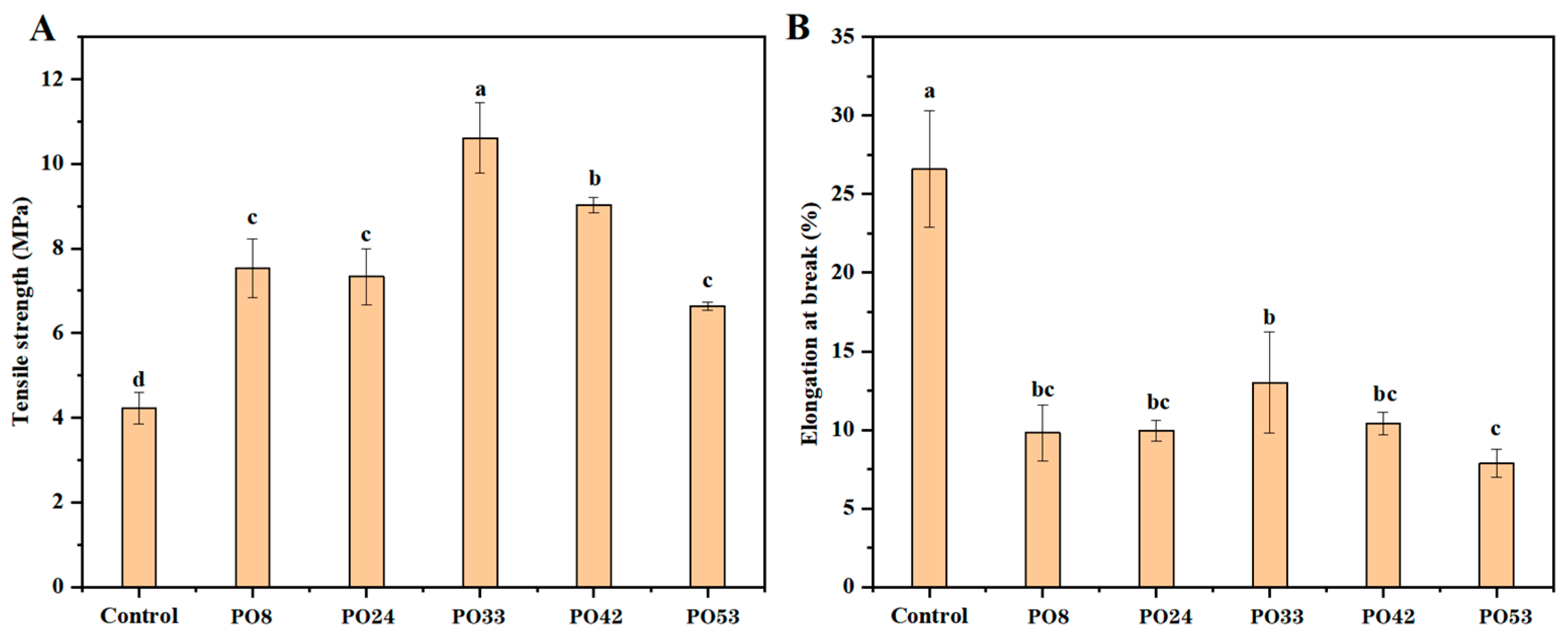

3.7. Mechanical Properties of Starch–PO Films

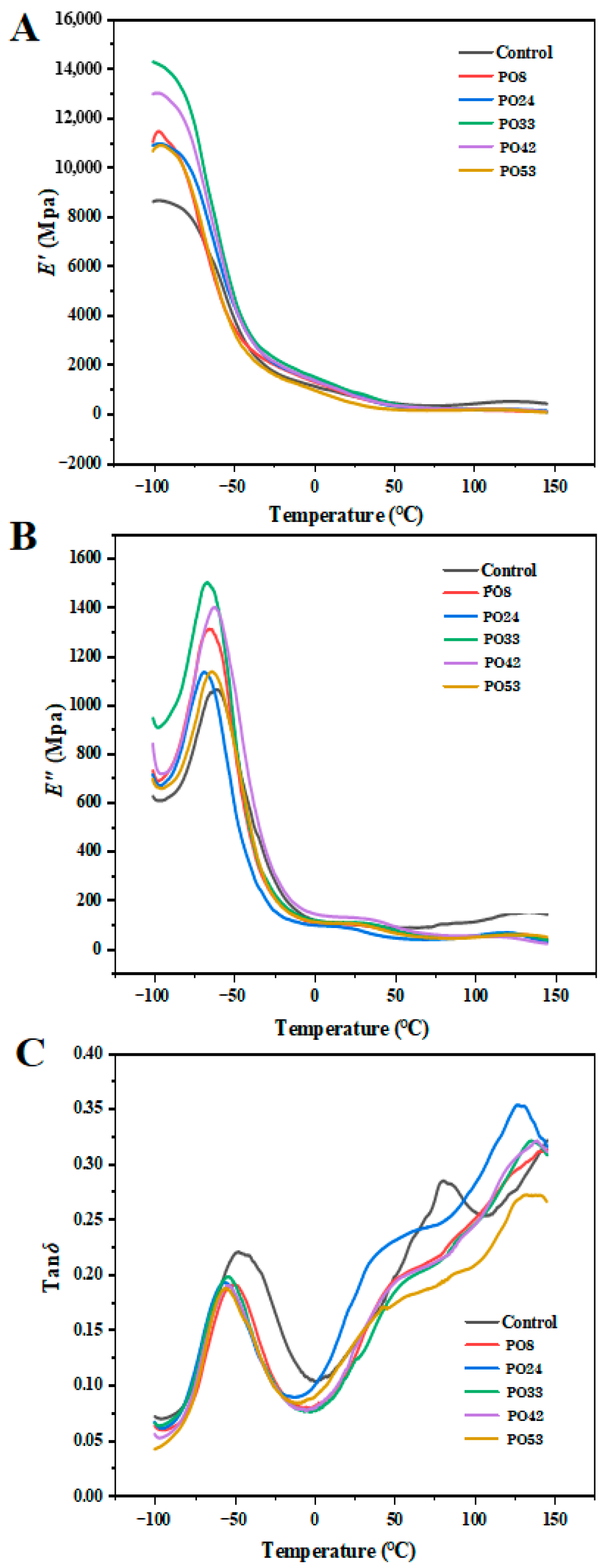

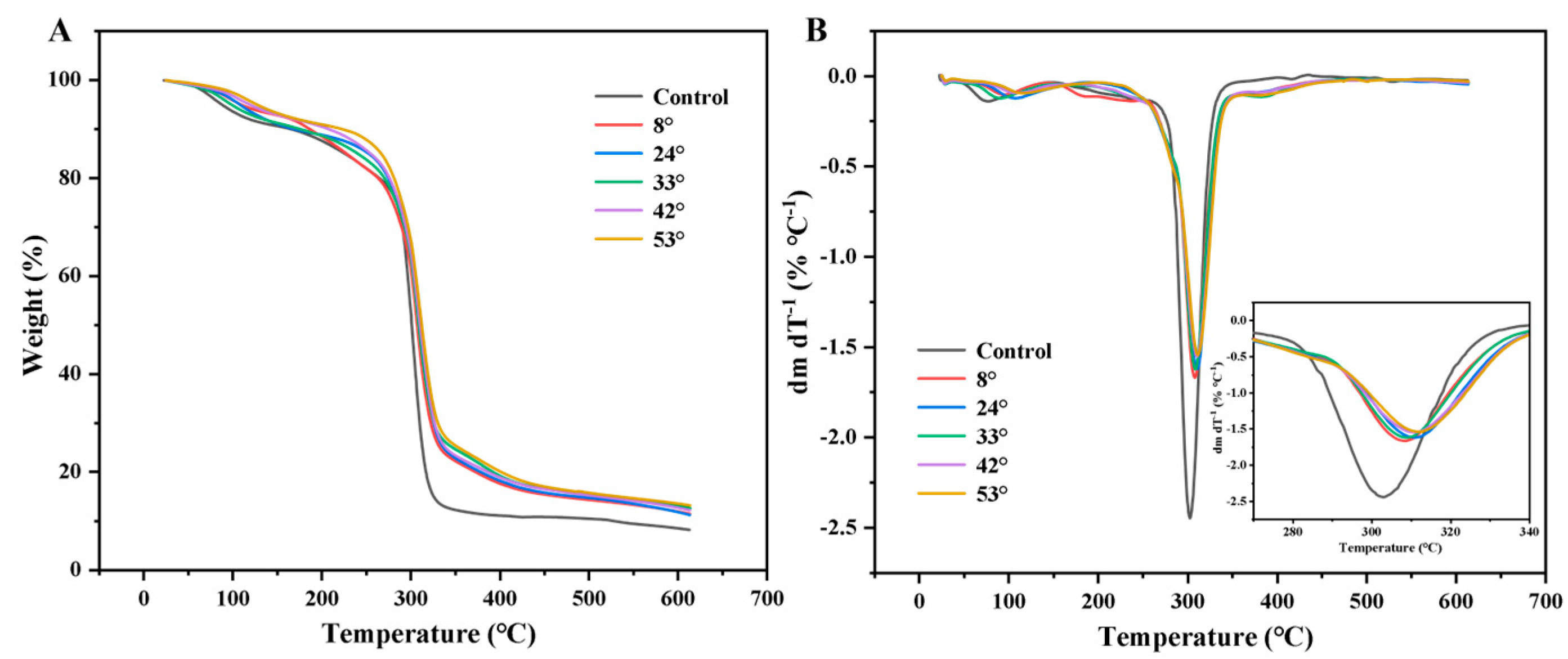

3.8. Thermal Properties of Films

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, C.; Ji, N.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Bioactive and intelligent starch-based films: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsakidou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Kiosseoglou, V. Preparation and characterization of composite sodium caseinate edible films incorporating naturally emulsified oil bodies. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Filho, J.G.d.; Bezerra, C.C.d.O.N.; Albiero, B.R.; Oldoni, F.C.A.; Miranda, M.; Egea, M.B.; Azeredo, H.M.C.d.; Ferreira, M.D. New approach in the development of edible films: The use of carnauba wax micro- or nanoemulsions in arrowroot starch-based films. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Ji, Y.; McClements, D.J.; Song, H.; Liu, R.; Gao, S.; Sun, C.; Hou, H.; Wang, W. Tailoring the hydrophobic structure of starch films: Selective distribution of beeswax via ultrasonication and homogenization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurul Syahida, S.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Ainun, Z.M.A.a.; Nur Hanani, Z.A. Effects of palm wax on the physical, mechanical and water barrier properties of fish gelatin films for food packaging application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Tang, C.-H.; Yin, S.-W.; Yang, X.-Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; Wei, Z.-H. Characterization of gelatin-based edible films incorporated with olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba, O.I.; Dumont, M.-J.; Ngadi, M. Palm oil: Processing, characterization and utilization in the food industry—A review. Food Biosci. 2015, 10, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T.; Nilsuwan, K. Emulsion film based on fish skin gelatin and palm oil: Physical, structural and thermal properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 48, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y. Impact of melting point of palm oil on mechanical and water barrier properties of gelatin-palm oil emulsion film. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 60, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Chai, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Nishinari, K.; Zhao, M.; Cui, B. Effect of emulsifiers on the properties of corn starch films incorporated with Zanthoxylum bungeanum essential oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Kong, F.; Xu, J.; Fernandes, F.; Evaristo, M.; Dong, S.; Cavaleiro, A.; Ju, H. Deciphering the mechanical strengthening mechanism: Soft metal doping in ceramic matrices—A case study of TiN-Ag films. Mater. Des. 2024, 248, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Sun, J. Investigating the effects of oil type, emulsifier type, and emulsion particle size on textured fibril soy protein emulsion-filled gels and soybean protein isolate emulsion-filled gels. J. Texture Stud. 2024, 55, e12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.; Sun, C.; Wang, W.; Hou, H. Effect of lipids with different physical state on the physicochemical properties of starch/gelatin edible films prepared by extrusion blowing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, C.; Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Nishinari, K.; Zhao, M.; Cui, B. Characterizations of corn starch edible films reinforced with whey protein isolate fibrils. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaee-Aliabadi, S.; Hosseini, H.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Mohammadi, A.; Ghasemlou, M.; Ojagh, S.M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Khaksar, R. Characterization of antioxidant-antimicrobial κ-carrageenan films containing Satureja hortensis essential oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 52, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sui, J.; Yu, B.; Yuan, C.; Guo, L.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Cui, B. Physicochemical properties and antibacterial activity of corn starch-based films incorporated with Zanthoxylum bungeanum essential oil. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Osés, J.; Ziani, K.; Maté, J.I. Combined effect of plasticizers and surfactants on the physical properties of starch based edible films. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Yu, D.; Mahdi, A.A.; Zhang, L.; Obadi, M.; Al-Ansi, W.; Xia, W. Influence of cellulose viscosity on the physical, mechanical, and barrier properties of the chitosan-based films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, T.C.; Marinho, C.O.; Marangoni Júnior, L.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Vieira, R.P. Essential oils as additives in active starch-based food packaging films: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Lei, Y.; Peng, L.; Chang, J.; Li, S.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Z. Effects of cinnamon essential oil-loaded Pickering emulsion on the structure, properties and application of chayote tuber starch-based composite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 240, 124444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; Pérez-Masiá, R.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Influence of the homogenization conditions and lipid self-association on properties of sodium caseinate based films containing oleic and stearic acids. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, R.; Qi, W.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Adjustable strength and toughness of dual cross-linked nanocellulose films via spherical cellulose as soft-phase. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 327, 121708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Dong, H.; Hou, H. Effects of hydrophobic agents on the physicochemical properties of edible agar/maltodextrin films. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 88, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.F.; Norcino, L.B.; Martins, H.H.A.; Manrich, A.; Otoni, C.G.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; Piccoli, R.H.; Oliveira, J.E.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Correlating emulsion characteristics with the properties of active starch films loaded with lemongrass essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 100, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, M.; Salami, M.; Momen, S.; Alavi, F.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. Enhancing the aqueous solubility of curcumin at acidic condition through the complexation with whey protein nanofibrils. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, T.; Peng, L.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Z. Development and characterization of antioxidant composite films based on starch and gelatin incorporating resveratrol fabricated by extrusion compression moulding. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; You, N.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, P. Effect of cellulose nanocrystals-loaded ginger essential oil emulsions on the physicochemical properties of mung bean starch composite film. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 116003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, J.; Yu, S.; Niu, R.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.; Ye, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, W. Active chitosan/gum Arabic-based emulsion films reinforced with thyme oil encapsulating blood orange anthocyanins: Improving multi-functionality. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 134, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, H.; Chong, E.W.N.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Paridah, M.T.; Gopakumar, D.; Tajarudin, H.A.; Thomas, S.; Abdul Khalil, H.P.S. Enhancement in the Physico-Mechanical Functions of Seaweed Biopolymer Film via Embedding Fillers for Plasticulture Application—A Comparison with Conventional Biodegradable Mulch Film. Polymers 2019, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Rusman, R.; Khaldun, I.; Ardana, L.; Mudatsir, M.; Fansuri, H. Active edible sugar palm starch-chitosan films carrying extra virgin olive oil: Barrier, thermo-mechanical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilah, A.N.; Jamilah, B.; Noranizan, M.A.; Hanani, Z.A.N. Utilization of mango peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodpran, T.; Benjakul, S.; Artharn, A. Properties and microstructure of protein-based film from round scad (Decapterus maruadsi) muscle as affected by palm oil and chitosan incorporation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 41, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresas, G.A.; Szabó, T.; Marossy, K. A comparative study of carboxylic acids on the cross-linking potential of corn starch films. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1277, 134886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, L.-j.; Li, D.; Mao, Z.-h.; Adhikari, B. Effect of flaxseed meal on the dynamic mechanical properties of starch-based films. J. Food Eng. 2013, 118, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, J.; He, J. Effects of cinnamon essential oil on the physical, mechanical, structural and thermal properties of cassava starch-based edible films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 184, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Liu, R.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, J. Preparation of starch-palmitic acid complex nanoparticles and their effect on properties of the starch composite film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | 10.0 wt% CS (g) | Nanoemulsions (PO = 1.0%, CAS = 0.25%) (g) | Water (g) | Glycerol (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 25.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.7 |

| PO8 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PO24 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PO33 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PO42 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PO53 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PO Nanoemulsions | Average Diameter (nm) | Polydispersity Index (Ð) |

|---|---|---|

| PO8 | 374.5 ± 27.3 c | 0.510 ± 0.040 b |

| PO24 | 447.8 ± 22.4 b | 0.508 ± 0.016 b |

| PO33 | 346.5 ± 17.2 c | 0.434 ± 0.063 b |

| PO42 | 524.0 ± 34.4 a | 0.771 ± 0.067 a |

| PO53 | 573.3 ± 39.1 a | 0.843 ± 0.052 a |

| Films | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 53.93 ± 0.25 b | 1.81 ± 0.40 ab | 2.24 ± 0.33 b | 0 |

| PO8 | 54.02 ± 0.54 b | 2.16 ± 0.10 ab | 2.34 ± 0.07 b | 0.56 ± 0.12 d |

| PO24 | 54.54 ± 0.37 ab | 1.49 ± 0.55 ab | 3.37 ± 0.28 a | 1.33 ± 0.05 b |

| PO33 | 52.84 ± 0.43 c | 2.29 ± 0.38 a | 3.54 ± 0.52 a | 1.74 ± 0.06 a |

| PO42 | 54.72 ± 0.38 a | 1.72 ± 0.68 ab | 2.68 ± 0.41 b | 0.92 ± 0.56 c |

| PO53 | 53.23 ± 0.12 c | 1.22 ± 0.59 b | 2.34 ± 0.39 b | 0.93 ± 0.13 c |

| Starch–PO Films | Thickness (mm) | Water Vapor Permeability (WVP) (1012 g·cm/cm2·s·Pa) | Moisture Content (%) | Total Soluble Matter Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 0.143 ± 0.002 e | 3.871 ± 0.04 a | 15.58 ± 0.58 a | 31.22 ± 0.21 a |

| PO8 | 0.190 ± 0.010 c | 3.403 ± 0.08 b | 14.64 ± 1.38 ab | 28.18 ± 0.14 b |

| PO24 | 0.201 ± 0.002 b | 3.070 ± 0.08 c | 13.03 ± 0.37 bc | 29.54 ± 1.60 ab |

| PO33 | 0.175 ± 0.003 d | 2.861 ± 0.07 d | 12.27 ± 0.28 c | 27.88 ± 0.29 b |

| PO42 | 0.193 ± 0.004 c | 3.206 ± 0.06 c | 13.02 ± 1.43 bc | 28.16 ± 0.39 b |

| PO53 | 0.225 ± 0.002 a | 3.708 ± 0.08 a | 14.52 ± 0.31 ab | 30.64 ± 1.40 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Chai, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, N.; Lu, L.; Zhao, M.; Cui, B. Effects of Palm Oil Nanoparticles in Diverse Physical States on the Properties of Starch Films. Foods 2026, 15, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010139

Zhang Y, Yang Q, Li Z, Chai Q, Zhang Z, Wang N, Lu L, Zhao M, Cui B. Effects of Palm Oil Nanoparticles in Diverse Physical States on the Properties of Starch Films. Foods. 2026; 15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yaqi, Qianwen Yang, Zhao Li, Qingqing Chai, Zheng Zhang, Na Wang, Lu Lu, Meng Zhao, and Bo Cui. 2026. "Effects of Palm Oil Nanoparticles in Diverse Physical States on the Properties of Starch Films" Foods 15, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010139

APA StyleZhang, Y., Yang, Q., Li, Z., Chai, Q., Zhang, Z., Wang, N., Lu, L., Zhao, M., & Cui, B. (2026). Effects of Palm Oil Nanoparticles in Diverse Physical States on the Properties of Starch Films. Foods, 15(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010139