Integrated Metabolomics and Flavor Profiling Provide Insights into the Metabolic Basis of Flavor and Nutritional Composition Differences Between Sunflower Varieties SH363 and SH361

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. LC-MS Sample Preparation

2.2.2. GC-MS Sample Preparation

2.3. Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Conditions

2.3.1. UPLC–MS/MS Conditions

2.3.2. GC–MS Conditions

2.4. Nutritional Component Analysis

2.4.1. Total Sugars

2.4.2. Crude Fat

2.4.3. Crude Protein

2.4.4. Starch

2.4.5. Cellulose

2.5. Sensory Attribute Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Quality Control

3.2. Metabolite Profiling of Sunflower Seeds

3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Metabolites

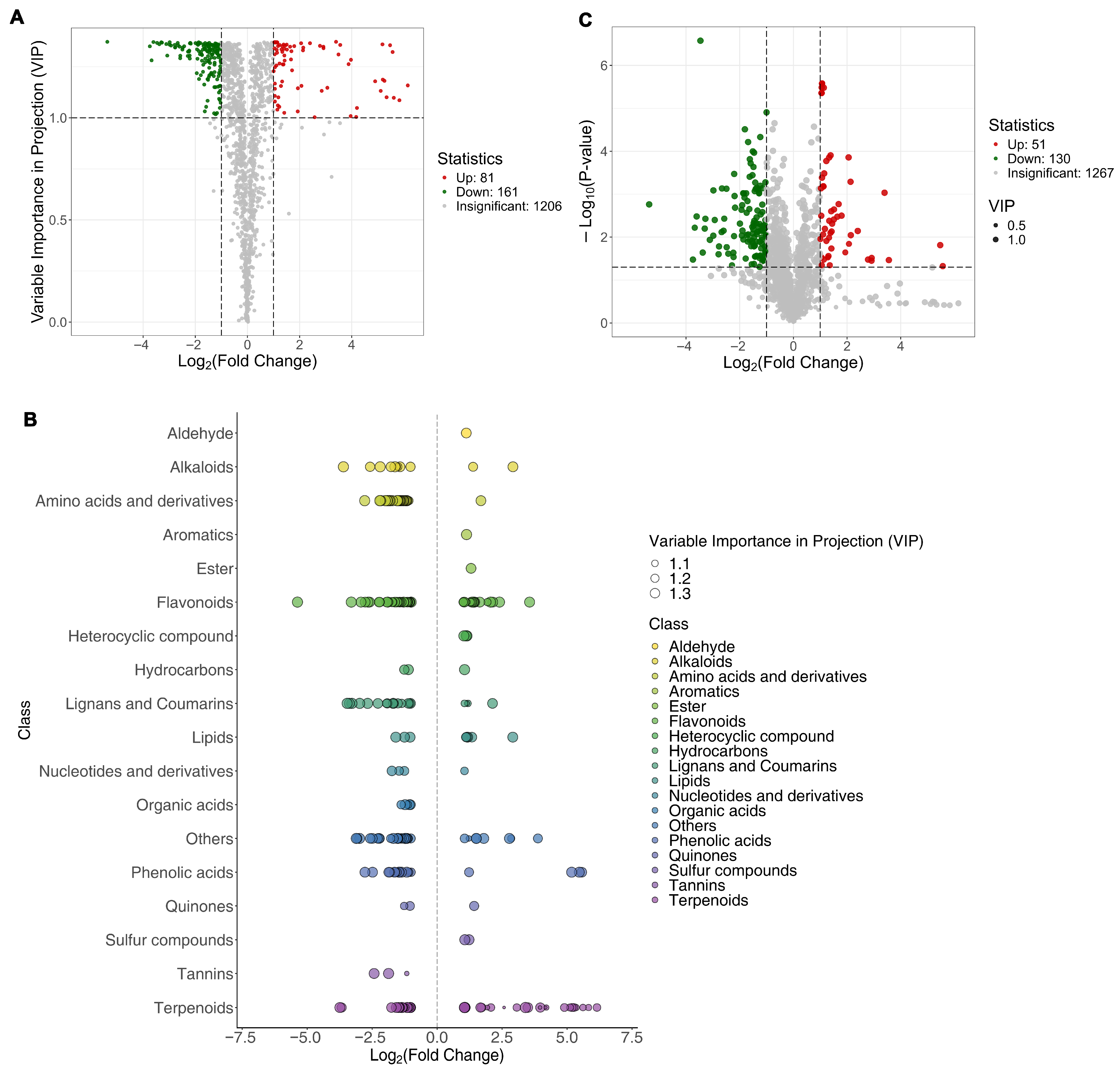

3.4. Differential Metabolites Between SH361 and SH363

3.5. Differential Metabolic Pathways Underlying Flavor Differences

3.6. Nutrient Composition Differences

3.7. Inferred Sensory Characteristics of Sunflower Seeds

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Metabolites Affecting Sunflower Quality

4.2. Metabolic Pathways Associated with Quality Differences

4.3. Metabolite—Sensory Relationships

4.4. Macronutrient Composition and Flavor

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Xiang, F.; Huang, X.; Liang, M.; Ma, S.; Gafurov, K.; Gu, F.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Q. Properties and characterization of sunflower seeds from different varieties of edible and oil sunflower seeds. Foods 2024, 13, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilorgé, E. Sunflower in the global vegetable oil system: Situation, specificities and perspectives. OCL 2020, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttha, R.; Venkatachalam, K.; Hanpakdeesakul, S.; Wongsa, J.; Parametthanuwat, T.; Srean, P.; Pakeechai, K.; Charoenphun, N. Exploring the potential of sunflowers: Agronomy, applications, and opportunities within bio-circular-green economy. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De'Nobili, M.D.; Bernhardt, D.C.; Basanta, M.F.; Rojas, A.M. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) seed hull waste: Composition, antioxidant activity, and filler performance in pectin-based film composites. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 777214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Jan, C.C.; Seiler, G. Breeding, production, and supply chain of confection sunflower in China. OCL 2022, 29, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynli, L.; Walser, C.; Blumenthaler, L.; Vene, K.; Dawid, C. Toward a comprehensive understanding of flavor of sunflower products: A review of confirmed and prospective aroma- and taste-active compounds. Foods 2025, 14, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Sun, H.; Ma, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Pei, H.; Li, X.; Gao, L. Insights into flavor and key influencing factors of Maillard reaction products: A recent update. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 973677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ninomiya, K. Umami and food palatability. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 921S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraru, A.; Ursachi, F.; Amariei, S. Nutritional characteristics assessment of sunflower seeds, oil and cake. Perspective of using sunflower oilcakes as a functional ingredient. Plants 2021, 10, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, B.; Goyal, A. Oilseeds: Health Attributes and Food Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancalon, P. Chemical composition of sunflower seed hulls. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1971, 48, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonechna, K.; Ilko, V.; Beríková, M.; Vietoris, V.; Panovská, Z.; Doleal, M. Nutritional, utility, and sensory quality and safety of sunflower oil on the central european market. Agriculture 2024, 14, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Duan, J.; Bao, Z.X. Preparation of sunflower seed-derived umami protein hydrolysates and their synergistic effect with monosodium glutamate and disodium inosine-5′-monophosphate. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 3332–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pathak, R.K.; Gayen, A.; Gupta, S.; Singh, M.; Lata, C.; Sharma, H.; Roy, J.K.; Gupta, S.M. Systems biology of seeds: Decoding the secret of biochemical seed factories for nutritional security. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.Y.; Ge, Y.Y.; Geng, F.; He, X.Q.; Xia, Y.; Guo, B.L.; Gan, R.Y. Antioxidant capacity, phytochemical profiles, and phenolic metabolomics of selected edible seeds and their sprouts. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1067597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, R.; Gethings, L.; Rainville, P.; Isaac, G.; Trengove, R.; King, A.M.; Wilson, I. Advances in high throughput LC/MS based metabolomics: A review. TrAC Trend. Anal. Chem. 2023, 160, 116954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefale, H.; You, J.; Zhang, Y.; Getahun, S.; Berhe, M.; Abbas, A.A.; Ojiewo, C.O.; Wang, L. Metabolomic insights into the multiple stress responses of metabolites in major oilseed crops. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denise, D.C.L.; Dutra, A.S.; Pontes, F.M.; Coelho Bezerra, F.T. Storage of sunflower seeds. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 2014, 45, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Wang, P.; Yan, Y.; Jiao, Z.W.; Xie, S.H.; Li, Y.; Di, P. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis provide insight into the biosynthesis of flavonoids in Panax japonicus. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangyu, M.; Fritz, M.; Tan, J.P.; Ye, L.; Bolten, C.J.; Bogicevic, B.; Wittmann, C. Flavour by design: Food-grade lactic acid bacteria improve the volatile aroma spectrum of oat milk, sunflower seed milk, pea milk, and faba milk towards improved flavour and sensory perception. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei-Ye, L.; Hong-Bo, G.; Rui-Heng, Y.; Ai-Guo, X.; Jia-Chen, Z.; Zhao-Qian, Y.; Wen-Jun, H.; Xiao-Dan, Y. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS-based widely targeted metabolomics reveals differences in metabolite composition among four Ganoderma species. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1335538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zang, L.; Ya, H. Widely targeted metabolomics analysis of different parts of Salsola collina Pall. Molecules 2021, 26, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, A.A.; Laponogov, I.; Zhang, Z.; Doran, S.L.F.; Belluomo, I.; Veselkov, D.; Bittremieux, W.; Nothias, L.F.; Nothias-Esposito, M.; Maloney, K.N.; et al. Auto-deconvolution and molecular networking of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.6-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Fat in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China & State Administration for Market Regulation of the People's Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016. Available online: http://down.foodmate.net/standard/sort/3/50382.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Method 960.39; Fat (Crude) in Meat and Food. AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.aoac.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- GB 5009.5-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Protein in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China & State Administration for Market Regulation of the People's Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/standard/GB%205009.5-2016 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Method 978.04; Nitrogen (Total) in Food (Kjeldahl Method). AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.aoac.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Yemm, E.W.; Willis, A.J. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J. 1954, 57, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Wine, R.H. Use of detergents in the analysis of fibrous feeds, IV. Determination of plant cell-wall constituents. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1967, 50, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, R.; Baosong, W.; Yue, D.; Huanlu, S.; Ali, R.; Dongfeng, W. Comprehensive characterization of the odor-active compounds in different processed varieties of Yunnan white tea (Camellia sinensis) by GC×GC-O-MS and chemometrics. Foods 2025, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Yu, C.; Guoming, W. Dissecting organ-specific aroma-active volatile profiles in two endemic phoebe species by integrated GC-MS metabolomics. Metabolites 2025, 15, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, Y.; Yao, H.; Lin, C.; Xie, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, A. Small molecule metabolites: Discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Tar. 2023, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Almenara, X.; Guijas, C.; Billings, E.; Montenegro-Burke, J.R.; Uritboonthai, W.; Aisporna, A.E.; Chen, E.; Benton, H.P.; Siuzdak, G. The METLIN small molecule dataset for machine learning-based retention time prediction. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Shu, N.; Wen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W. Widely targeted metabolomics was used to reveal the differences between non-volatile compounds in different wines and their associations with sensory properties. Foods 2023, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Quan, C.; Xu, M.; Wei, F.; Tang, D. Widely targeted metabolomics reveals the phytoconstituent changes in Platostoma palustre leaves and stems at different growth stages. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1378881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Tzur, D.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Guo, A.C.; Young, N.; Cheng, D.; Jewell, K.; Arndt, D.; Sawhney, S.; et al. HMDB: The Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D521–D526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, H.; Wei, R.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Xie, T.; Guo, R.; Zhou, S. Widely targeted metabolomics profiling reveals the effect of powdery mildew on wine grape varieties with different levels of tolerance to the disease. Foods 2022, 11, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Lu, Y.; Salavati, R.; Basu, N.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalystR 4.0: A unified LC-MS workflow for global metabolomics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Feng, T.; Xiong, C.; Nie, Q. Metabolome comparison of Sichuan dried orange peels (Chenpi) aged for different years. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, I.; Kumar Pandey, V.; Shams, R.; Dar, A.H.; Dash, K.K.; Khan, S.A.; Bashir, I.; Jeevarathinam, G.; Rusu, A.V.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; et al. Promising bioactive properties of quercetin for potential food applications and health benefits: A review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 999752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Li, X.; Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Shen, B.; Li, X. Association of bitter metabolites and flavonoid synthesis pathway in jujube fruit. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 901756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, G.S.; Yin, J.F.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.Q. Effects of phenolic acids and quercetin-3-O-rutinoside on the bitterness and astringency of green tea infusion. NPJ Sci. Food 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyita, A.; Sari, R.M.; Astuti, A.D.; Yasir, B.; Rumata, N.R.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem.-X 2022, 13, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautela, A.; Yadav, I.; Gangwar, A.; Chatterjee, R.; Kumar, S. Photosynthetic production of alpha-farnesene by engineered Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973 from carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 396, 130432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, C.F.; Cutignano, A.; Speranza, G.; Abbamondi, G.R.; Rabuffetti, M.; Iodice, C.; De Prisco, R.; Tommonaro, G. Taste compounds and polyphenolic profile of tomato varieties cultivated with beneficial microorganisms: A chemical investigation on nutritional properties and sensory qualities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Du, J.; Zhu, D.; Li, X.; Li, X. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses of anthocyanin biosynthesis mechanisms in the color mutant Ziziphus jujuba cv. Tailihong. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 15186–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Mi, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Cao, X.; Wan, H.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Genome-wide identification of key enzyme-encoding genes and the catalytic roles of two 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in Cannabis sativa L. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, D.K.; Alerding, A.B.; Crosby, K.C.; Bandara, A.B.; Westwood, J.H.; Winkel, B.S. Functional analysis of a predicted flavonol synthase gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1046–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, H.; Qi, D.; Dong, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y. Integrated omics reveal the mechanisms underlying softening and aroma changes in pear during postharvest storage and the role of melatonin. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Dupas de Matos, A.; Oduro, A.F.; Hort, J. Sensory characteristics of plant-based milk alternatives: Product characterisation by consumers and drivers of liking. Food Res. Int. 2024, 180, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Xian, Y.; Peng, K.; Liu, K.; Jiang, B. Exploring the effect of different tea varieties on the quality of Sichuan Congou black tea based on metabolomic analysis and sensory science. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1587413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter (% Dry Weight) | SH361 (Mean ± SD) | SH363 (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total sugars | 31.96 ± 1.91 | 24.62 ± 2.65 |

| Crude fat | 23.77 ± 0.06 | 51.01 ± 0.54 |

| Crude protein | 26.96 ± 0.32 | 26.08 ± 0.39 |

| Starch | 2.00 ± 1.4 | 2.00 ± 0.3 |

| Cellulose | 3.37 ± 3.97 | 3.57 ± 3.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Gong, H.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, J. Integrated Metabolomics and Flavor Profiling Provide Insights into the Metabolic Basis of Flavor and Nutritional Composition Differences Between Sunflower Varieties SH363 and SH361. Foods 2026, 15, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010106

Li Y, Gong H, Cui X, Wang X, Chen Y, Li H, Zhao J. Integrated Metabolomics and Flavor Profiling Provide Insights into the Metabolic Basis of Flavor and Nutritional Composition Differences Between Sunflower Varieties SH363 and SH361. Foods. 2026; 15(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yanli, Huihui Gong, Xinxiao Cui, Xin Wang, Ying Chen, Huiying Li, and Junsheng Zhao. 2026. "Integrated Metabolomics and Flavor Profiling Provide Insights into the Metabolic Basis of Flavor and Nutritional Composition Differences Between Sunflower Varieties SH363 and SH361" Foods 15, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010106

APA StyleLi, Y., Gong, H., Cui, X., Wang, X., Chen, Y., Li, H., & Zhao, J. (2026). Integrated Metabolomics and Flavor Profiling Provide Insights into the Metabolic Basis of Flavor and Nutritional Composition Differences Between Sunflower Varieties SH363 and SH361. Foods, 15(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010106