A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection

Abstract

1. Introduction

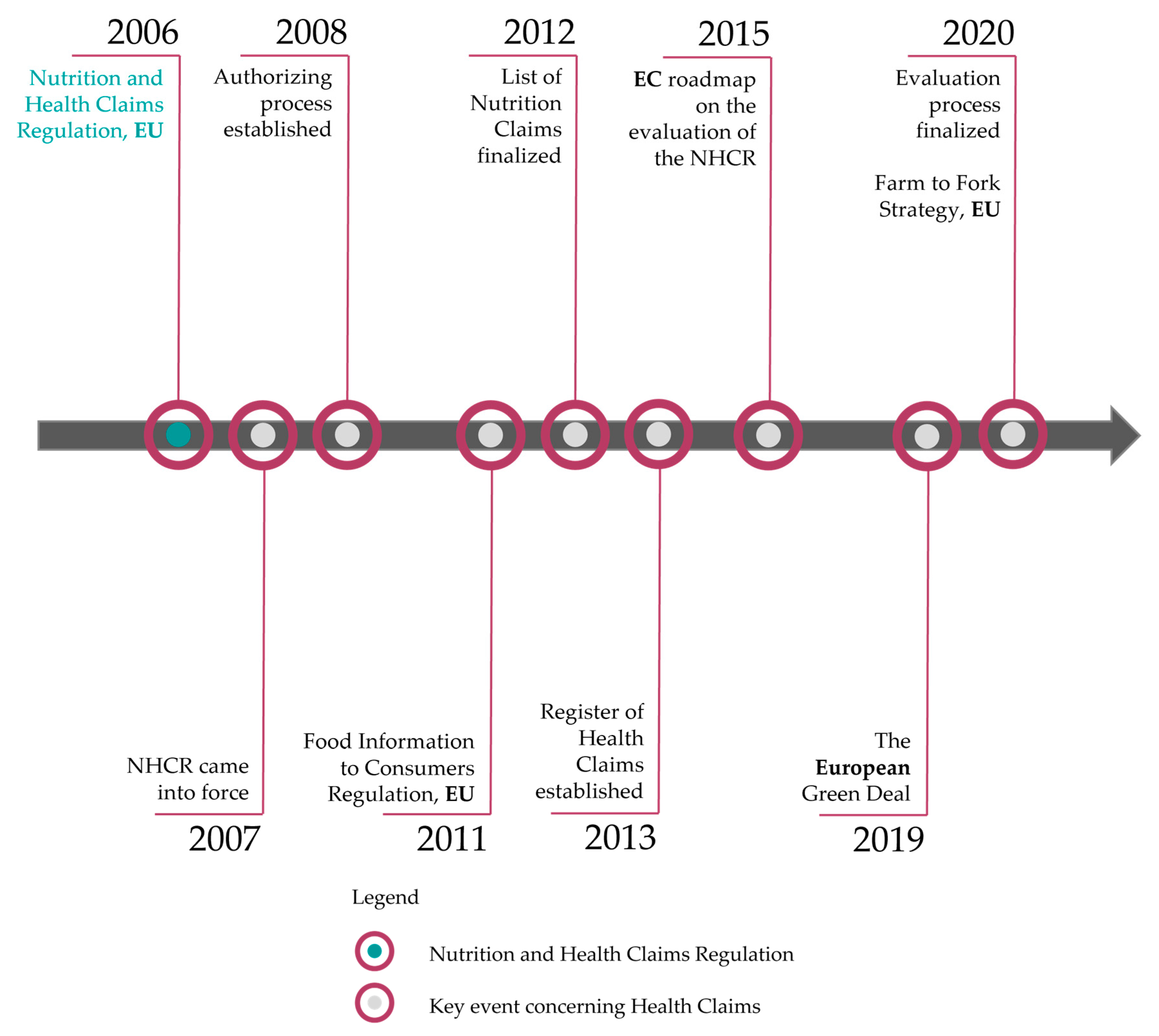

2. Historical Outline on the Development of Nutrition and Health Claims Since 2006

2.1. The Setting of Nutrient Profiles

- the quantities of certain nutrients and other substances contained in the food, such as fat, saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids, sugars and salt/sodium;

- the role and importance of the food (or of categories of foods) in the diet of the population in general or, as appropriate, of certain risk groups including children;

- the overall nutritional composition of the food and the presence of nutrients that have been scientifically recognized as having an effect on health.”

- The Joint Research Centre released a report on food labeling, encompassing nutrient profiles and FOPNL [46].

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issued updated scientific advice on nutrient profiles and FOPNL [47].

- The European Parliament (EP) published a resolution on bolstering Europe’s efforts against cancer, emphasizing the crucial need to “encourage and help consumers make informed, healthy and sustainable choices about food products” [48].

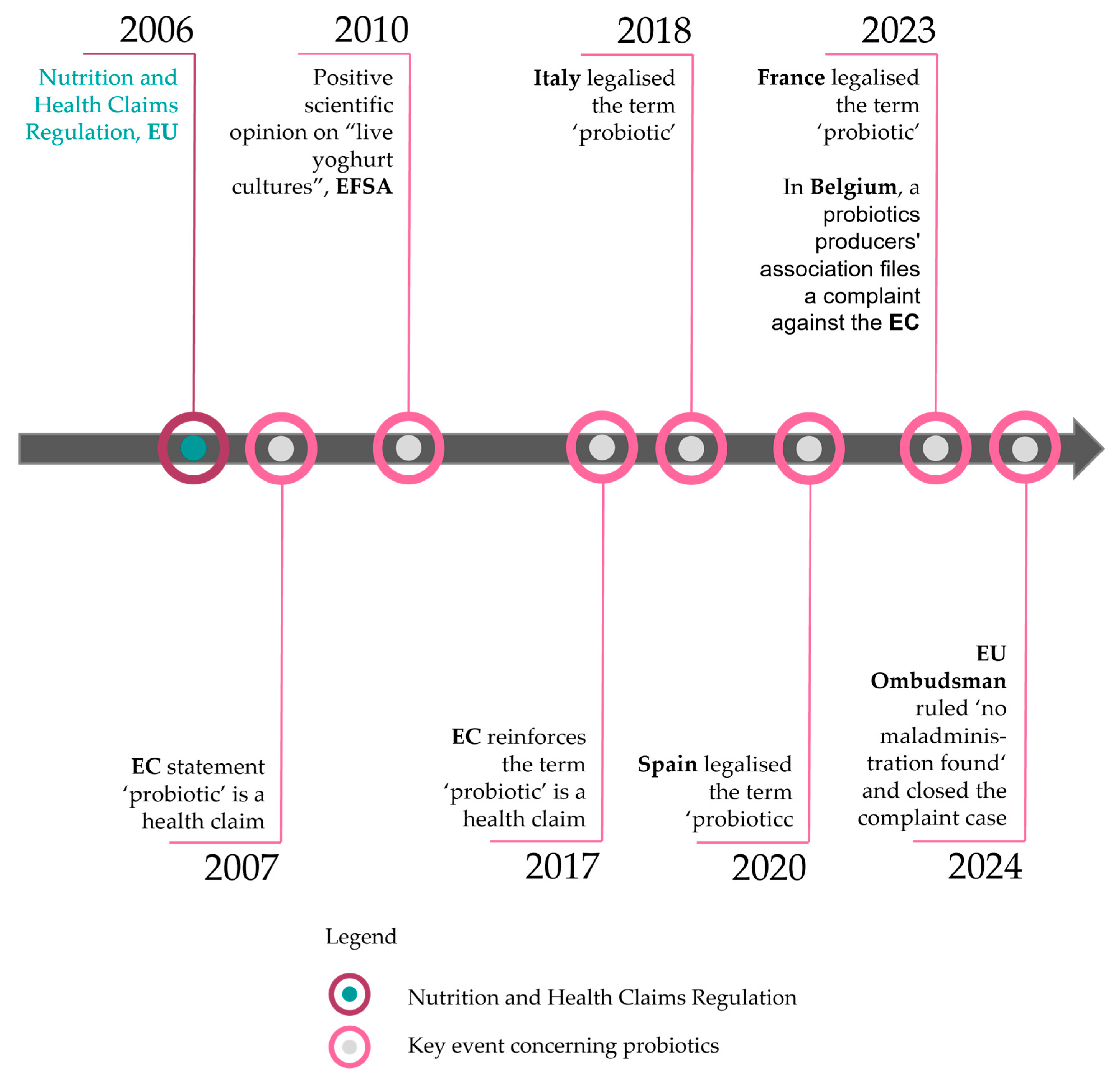

2.2. The Legal Fit for Probiotics

3. Discussion

3.1. Nutrient Profiles—Challenges and Opportunities to Achieve Consumer Protection

3.1.1. Nutrient Profiles: Challenges

- (a)

- EU institutions and authorities address different opinions

- (b)

- Misleading marketing information on food products

- (c)

- Consumers’ buying decisions are not exclusively driven by health

- (d)

- Various labels on the European market

- In Finland, the “Heart Symbol system” is utilized [85];

- Italy employs the “NutrInform Battery” scheme [87];

- The “Keyhole” symbol is used in EU Nordic member states such as Sweden or Denmark [75].

3.1.2. Nutrient Profiles: Opportunities

- (a)

- Nutrient profiles support healthy buying decisions

- (b)

- A European front-of-pack nutrition labeling scheme strengthens consumer trust

- (c)

- Specific nutrients can be considered to foster public heath

- (d)

- Nutrition policy should focus on consumers’ health

3.2. Probiotics—Challenges and Opportunities to Achieve Facilitation of Trade

3.2.1. Probiotics: Challenges

- (a)

- An unregulated start fosters errors in the beginning of regulating

- (b)

- Safety concerns in a rapidly evolving probiotics market

- (c)

- Impacts of a diverse landscape of probiotic regulation on the industry

3.2.2. Probiotics: Opportunities

- (a)

- Prioritize the advancement of consumer protection in political agendas

- (b)

- Clarification promotes harmonization

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEUC | The European Consumer Organization |

| EC | European Commission |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| EP | European Parliament |

| EU | European Union |

| FDA | US Food and Drug Administration |

| FICR | Food Information to Consumers Regulation |

| FOPNL | front-of-pack nutrition labeling |

| FOSHU | Food for Specified Health Uses |

| FUFOSE | Functional Food Science in Europe |

| NCDs | non-communicable diseases |

| NHCR | EU’s Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation |

| PASSCLAIM | Process for the assessment of scientific support for claims on foods |

| U. S. | United States |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Rivlin, R.S. Historical perspective on the use of garlic. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 951S–954S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F. TCM: Made in China. Nature 2011, 480, S82–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Tan, X.; Shi, H.; Xia, D. Nutrition and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): A system’s theoretical perspective. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaz, G.A. Chapter 19—An Overview on the History of Sports Nutrition Beverages. In Nutrition and Enhanced Sports Performance, 2nd.; Bagchi, D., Nair, S., Sen, C.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Diplock, A.T.; Aggett, P.J.; Ashwell, M.; Bornet, F.; Fern, E.B.; Roberfroid, M.B. Scientific Concepts of Functional Foods in Europe Consensus Document. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, C.; Gardiner, G.; Meehan, H.; Collins, K.; Fitzgerald, G.; Lynch, P.B.; Ross, R.P. Market potential for probiotics. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 476S–483S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.B. Looking into the future of foods and health. Innovation 2008, 10, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Health Risks and Issues—Diet. 2023. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/health-risks-issues/diet (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Eriksson, G.; Machin, D. Discourses of ‘Good Food’: The commercialization of healthy and ethical eating. Discourse Context Media 2020, 33, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatani, S.; Yamamoto, N. Functional food products in Japan: A review. Food Sci. Human Wellness 2019, 8, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T. Health Claims and Scientific Substantiation of Functional Foods—Japanese Regulatory System and the International Comparison. Eur. Food Feed Law. Rev. 2011, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, J.A. Functional foods: The US perspective. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1654S–1659S, discussion 1674S–1675S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA—U. S. Food & Drug Administration. Use of the Term Healthy on Food Labeling. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/use-term-healthy-food-labeling (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2006, 404, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Neal, B.; Dixon, H.; Hughes, C.; Kelly, B.; Miller, C. Consumers’ responses to health claims in the context of other on-pack nutrition information: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA—U. S. Food & Drug Administration. Authorized Health Claims That Meet the Significant Scientific Agreement (SSA) Standard. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/authorized-health-claims-meet-significant-scientific-agreement-ssa-standard (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- FDA—U. S. Food & Drug Administration. Questions and Answers on Health Claims in Food Labeling. 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/questions-and-answers-health-claims-food-labeling (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- European Commission. Evaluation of the Regulation on Nutrition and Health Claims. 2023. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/labelling-and-nutrition/nutrition-and-health-claims/evaluation-regulation-nutrition-and-health-claims_en#staff-working-document---key-findings (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. Nutrient Profile Model: WHO Regional Office for Europe; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J.; Loh, W.M.L.; Ooi, Y.B.H.; Khor, B. Characteristics and nutrient profiles of foods and beverages on online food delivery systems. Nutr. Bull. 2025. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, G.W.; Detzel, P.; Grunert, K.G.; Robert, M.-C.; Stancu, V. Towards effective labelling of foods. An international perspective on safety and nutrition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Rito, A.I.; Matias, F.N.; Assunção, R.; Castanheira, I.; Loureiro, I. Nutrient profile models a useful tool to facilitate healthier food choices: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonté, M.; Poon, T.; Gladanac, B.; Ahmed, M.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Rayner, M.; L’Abbé, M.R. Nutrient Profile Models with Applications in Government-Led Nutrition Policies Aimed at Health Promotion and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 741–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. European market developments in prebiotic- and probiotic-containing foodstuffs. Br. J. Nutr. 1998, 80, S231–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila-Sandholm, T.; Myllärinen, P.; Crittenden, R.; Mogensen, G.; Fondén, R.; Saarela, M. Technological challenges for future probiotic foods. Int. Dairy. J. 2002, 12, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Estimated Value of Probiotics Market Worldwide from 2022 to 2027. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/821259/global-probioticsl-market-value/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Statista. Market Share of Probiotic Products Worldwide 2021, by Selected Category. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/911817/global-probiotic-products-market-share-by-category/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Danone GmbH. Bereits Seit 30 Jahren Hilft Actimel Bei der Unterstützung des Immunsystems. 2025. Available online: https://www.actimel.de/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Euromonitor. Probiotics No Longer Differentiating in Dairy Products. 2021. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/video/probiotics-no-longer-differentiating-in-dairy-products (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- European Commission. Nutrition Claims. 2025. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/labelling-and-nutrition/nutrition-and-health-claims/nutrition-claims_en#permitted-nutrition-claims (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1047/2012 of 8 November 2012 amending Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 with regard to the list of nutrition claims. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 55, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2008 of 18 April 2008 establishing implementing rules for applications for authorisation of health claims as provided for in Article 15 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 51, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) No 536/2013 of 11 June 2013 amending Regulation (EU) No 432/2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 56, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Register of Health Claims. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/food-feed-portal/screen/health-claims/eu-register (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document: Evaluation of the Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods with Regard to Nutrient Profiles and Health Claims Made on Plants and Their Preparations and of the General Regulatory Framework for Their Use in Foods: Part 2. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/labelling_nutrition-claims_swd_2020-95_part-2.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_6691 (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Farm to Fork Strategy: For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381 (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Commission. Eavluation and Fitness Check (FC) Roadmap. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/roadmaps/docs/2015_sante_595_evaluation_health_claims_en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- European Parliament. Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme European Parliament Resolution of 12 April 2016 on Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT): State of Play and Outlook. 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2016-0104_EN.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers: Amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, 54, 18–63. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Farm to Fork Strategy. European Parliament Resolution of 20 October 2021 on a Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0425_EN.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Regarding the Use of Additional Forms of Expression and Presentation of the Nutrition Declaration. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/labelling-nutrition_fop-report-2020-207_en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Commission. Facilitating Healthier Food Choices—Establishing Nutrient Profiles. Public Consultation. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12748-Facilitating-healthier-food-choices-establishing-nutrient-profiles_en (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Commission. Food Labelling—Revision of Rules on Information Provided to Consumers. Public Consultation. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12749-Food-labelling-revision-of-rules-on-information-provided-to-consumers/public-consultation_en (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Nohlen, H.; Bakogianni, I.; Grammatikaki, E.; Ciriolo, E.; Pantazi, M.; Dias, J.; Salesse, F.; Moz Christofoletti, M.; Wollgast, J.; Bruns, H.; et al. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Schemes: An update of the Evidence: Addendum to the JRC Science for Policy Report “Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Schemes: A Comprehensive Review”; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Volume 31153. [Google Scholar]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A. Scientific advice related to nutrient profiling for the development of harmonised mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labelling and the setting of nutrient profiles for restricting nutrition and health claims on foods. EFS2 2022, 20, e07259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Strengthening Europe in the Fight Against Cancer European Parliament Resolution of 16 February 2022 on Strengthening Europe in the Fight Against Cancer—Towards a Comprehensive and Coordinated Strategy. 2022. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0038_EN.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Parliament. Proposal for a Harmonised Mandatory Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling—In “A European Green Deal”. 2025. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/carriage/mandatory-front-of-pack-nutrition-labelling/report?sid=8901 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Commission. Guidance on the Implementation of Regulation N° 1924/2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Food—Conclusions of the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. 2007. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files_en?file=2016-10/labelling_nutrition_claim_reg-2006-124_guidance_en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- European Commission. Probiotic in Europe. 2023. Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/events/probiotics-europe-how-can-better-regulation-strengthen-knowledge-probiotics-consumer-health_en (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- FAO; WHO. Probiotics in Food: Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food, Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria: Cordoba, Argentina, 1–4 October 2001: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Working Group on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper, 0254-4725; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006; Volume 85. [Google Scholar]

- Pedicini, P. Use of the Term ‘Probiotic’ and Nutrition Claims: Question for Written Answer E-004201-17 to the Commission. 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2017-004201_EN.html (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- European Commission. Answer Given by Mr Andriukaitis on Behalf of the Commission: Parliamentary Question—E-004201/2017(ASW). 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2017-004201-ASW_EN.html (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Ministère de L’économie des Finances et de la Souveraineté Industrielle et Numérique. Allégations Nutritionnelles et de Santé: Ne Vous Faites pas Avoir! 2024. Available online: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/dgccrf/les-fiches-pratiques/allegations-nutritionnelles-et-de-sante-ne-vous-faites-pas-avoir (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Ministero Della Salute. Guidelines on Probiotics an Prebiotics. 2018. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1016_ulterioriallegati_ulterioreallegato_0_alleg.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- AESAN—Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Probióticos en los Alimentos. 2020. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/seguridad_alimentaria/subdetalle/probioticos.htm?idU=1&utm_source=newsletter_1712&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=importante-probioticos-etiquetado (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Statista. Number of DAIRY Companies for SELECTED Countries in Europe in 2016, by Country. 2016. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/630796/number-of-dairy-companies-in-european-union-eu/ (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Statista. Revenue of the Milk Substitutes Market in the European Union (EU-27) in 2021 (in Million U. S. Dollars), by Country. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1343401/eu-milk-substitute-market-revenue (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- European Central Bank. Exchange Rate US Dollar in Euros—Average 2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/euro_reference_exchange_rates/html/eurofxref-graph-usd.en.html (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Statista. Turnover of Dairy Product in Europe in 2019, by Leading Country. 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1236920/dairy-industry-turnover-by-leading-countries-europe/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Jost, S.; Birringer, M.; Herzig, C. Brokers, prestige and information exchange in the European Union’s functional food sector—A policy network analysis. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 99, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Probiotic Association (IPA) Europe. Probiotics in the EU: Different Approaches in European Countries. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipaeurope.org/legal-framework/european-legal-framework/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Ridley, D. France Becomes Latest EU Member to Allow ‘Probiotic’ Label for Dietary Supplements. 2023. Available online: https://hbw.pharmaintelligence.informa.com/RS153261/France-Becomes-Latest-EU-Member-To-Allow-Probiotic-Label-For-Dietary-Supplements (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Analyze & Realize. France Allows the Claim “Probiotic” on Food Supplements. 2023. Available online: https://www.a-r.com/france-allows-the-claim-probiotic-on-food-supplements/ (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- European Ombudsman. Decision on How the European Commission Deals with the Labelling of Foodstuff that Contain Probiotics as ‘Health Claims’ (Case 2273/2023/MIK). 2024. Available online: https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/197581 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- European Parliament. Parliament Vetoes Energy Drink “Alertness” Claims. 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20160701IPR34496/parliament-vetoes-energy-drink-alertness-claims (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/8 of 6 January 2015 refusing to authorise certain health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health. Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, 58, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband, e.V. Nahrungsergänzungsmittel Sicher Regulieren. 2023. Available online: https://www.verbraucherzentrale.de/sites/default/files/2023-08/23-08-10_positionspapier-vzbv-und-vzn-nem.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on the addition of vitamins and minerals and of certain other substances to foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 49, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, M.; Deforche, B.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Michels, N.; Geuens, M.; Van Lippevelde, W. Intervention strategies to promote healthy and sustainable food choices among parents with lower and higher socioeconomic status. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Food Marketing Exposure and Power and Their Associations with Food-Related Attitudes, Beliefs, and Behaviours: A Narrative Review. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041783 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Merz, B.; Temme, E.; Alexiou, H.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Buyken, A.E.; Bohn, T.; Ducrot, P.; Falquet, M.-N.; Solano, M.G.; Haidar, H.; et al. Nutri-Score 2023 update. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassy, M.; van Dijk, R.; Eldridge, A.L.; Mak, T.N.; Drewnowski, A.; Feskens, E.J. Nutrient Profiling Models in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Considering Local Nutritional Challenges: A Systematic Review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2025, 9, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Food Research Program at UNC-Chapel Hill. Front-of-Package Labels Around the World. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalfoodresearchprogram.org/resource/front-of-package-label-maps/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Saviolidis, N.M.; Olafsdottir, G.; Nicolau, M.; Samoggia, A.; Huber, E.; Brimont, L.; Gorton, M.; von Berlepsch, D.; Sigurdardottir, H.; Del Prete, M.; et al. Stakeholder Perceptions of Policy Tools in Support of Sustainable Food Consumption in Europe: Policy Implications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønnesen, M.T.; Hansen, S.; Laasholdt, A.V.; Lähteenmäki, L. The impact of positive and reduction health claims on consumers’ food choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, C.; Grunert, K.; Christensen, R.N.; Boncinelli, F.; Scozzafava, G.; Casini, L. Does attitude moderate the effect of labelling information when choosing functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 106, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Grunert, K.G. The role of time constraints in consumer understanding of health claims. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, L. Claiming health in food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttinen, H.; Halmesvaara, O.; Fogelholm, M.; Saarijärvi, H.; Nevalainen, J.; Erkkola, M. Sociodemographic differences in motives for food selection: Results from the LoCard cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Bucher, T.; Egan, B.; Dean, M. Are the Claims to Blame? A Qualitative Study to Understand the Effects of Nutrition and Health Claims on Perceptions and Consumption of Food. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, G.W.; Grunert, K.G.; Lähteenmäki, L. Supporting consumers’ informed food choices: Sources, channels, and use of information. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 104, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzù, M.F.; Baccelloni, A.; Romani, S. Counteracting noncommunicable diseases with front-of-pack nutritional labels’ informativeness: An inquiry into the effects on food acceptance and portions selection. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantola, M.; Kara, A.; Lahti-Koski, M.; Luomala, H. The Effect of Nutrition Label Type and Consumer Characteristics on the Identification of Healthy Foods in Finland. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 37, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peonides, M.; Knoll, V.; Gerstner, N.; Heiss, R.; Frischhut, M.; Gokani, N. Food labeling in the European Union: A review of existing approaches. IJHG 2022, 27, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Galan, P.; Andreeva, V.A.; Vandevijvere, S.; Gombaud, M.; Dréano-Trécant, L.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Objective understanding of the Nutri-score front-of-pack label by European consumers and its effect on food choices: An online experimental study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, C.; Matzdorf, B.; Rommel, J.; Czajkowski, M.; García-Llorente, M.; Gutiérrez-Briceño, I.; Larsson, L.; Zagórska, K.; Zawadzki, W. Between farms and forks: Food industry perspectives on the future of EU food labelling. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 217, 108066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.F.; de Carvalho-Ferreira, J.P.; da Cunha, D.T.; De Rosso, V.V. Front-of-package nutrition labeling as a driver for healthier food choices: Lessons learned and future perspectives. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 535–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Russell, S.J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M. Front of pack nutritional labelling schemes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence relating to objectively measured consumption and purchasing. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklavec, K.; Pravst, I.; Raats, M.M.; Pohar, J. Front of package symbols as a tool to promote healthier food choices in Slovenia: Accompanying explanatory claim can considerably influence the consumer’s preferences. Food Res. Int. 2016, 90, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnal, N.; Machiels, C.J.; Orth, U.R.; Mai, R. Healthy by design, but only when in focus: Communicating non-verbal health cues through symbolic meaning in packaging. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastak, M.; Mitra, A.; Ringold, D.J. Do consumers view the nutrition facts panel when making healthfulness assessments of food products? Antecedents and consequences. J. Consum. Aff. 2020, 54, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Use of Nutrient Profile Models for Nutrition and Health Policies: Meeting Report on the Use of Nutrient Profile Models in the WHO European Region, September 2021, Copenhagen. 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/363379/WHO-EURO-2022-6201-45966-66383-eng.pdf?sequence=4 (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- European Public Health Association. Feedback from: European Public Health Association (EUPHA) on Establishing Nutrient Profiles. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12748-Facilitating-healthier-food-choices-establishing-nutrient-profiles/F1577124_en (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- BEUC. From Influence to Responsibility—Time to Regulate Influencer Marketing. 2023. Available online: https://www.beuc.eu/position-papers/influence-responsibility-time-regulate-influencer-marketing (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Laaninen, T. Briefing: Nutrient Profiles. A ‘Farm to Fork’ Strategy Initiative Takes Shape. 2022. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/729388/EPRS_BRI(2022)729388_EN.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Dolgopolova, I.; Teuber, R. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Health Benefits in Food Products: A Meta-Analysis. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A.; Vecchio, R. Effectiveness of sustainability labels in guiding food choices: Analysis of visibility and understanding among young adults. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre. Evidence on Food Information—Empowering Consumers to Make Healthy and Sustainable Choices. 2022. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/evidence-food-information-empowering-consumers-make-healthy-and-sustainable-choices-2022-09-09_en (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- European Food Safety Authority. FAQs on EFSA’s Scientific Advice Related to Nutrient Profiling for Harmonised Front-of-Pack Labelling and Restriction of Claims on Foods. 2022. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/topic/faq-nutrient-profiling-mandate.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- European Commission. Timeline of Farm to Fork Actions. 2022. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-04/f2f_timeline-actions_en.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Cerk, K.; Aguilera-Gómez, M. Microbiota analysis for risk assessment: Evaluation of hazardous dietary substances and its potential role on the gut microbiome variability and dysbiosis. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e200404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Elinav, E. Probiotics in the next-generation sequencing era. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merenstein, D.; Pot, B.; Leyer, G.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Preidis, G.A.; Elkins, C.A.; Hill, C.; Lewis, Z.T.; Shane, A.L.; Zmora, N.; et al. Emerging issues in probiotic safety: 2023 perspectives. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2185034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority. EFSA Remit & Role: With Focus on Scientific Substantiation of Health Claims Made on Foods: EFSA Meeting with IPA Europe. 2019. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/event/190118-ax.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Binnendijk, K.H.; Rijkers, G.T. What is a health benefit? An evaluation of EFSA opinions on health benefits with reference to probiotics. Benef. Microbes 2013, 4, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburger, S.; Birringer, M. European Health Claims for Small and Medium-Sized Companies – Utopian Dream or Future Reality? FFHD 2015, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FoodDrinkEurope. Data & Trends 2024. EU Food and Drink Industry. 2025. Available online: https://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/FoodDrinkEurope-Data-Trends-2024.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Voigt, S. How (Not) to measure institutions. J. Institutional Econ. 2013, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, D. Definition: Was Ist “Institution”? 2018. Available online: https://wirtschaftslexikon.gabler.de/definition/institution-37388/version-260824 (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Denzau, A.T.; North, D.C. Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions. Kyklos 1994, 47, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Brandenburger, S.; Türpe, S.; Birringer, M. The Need for a Legal Distinction of Nutraceuticals. FNS 2014, 05, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, H.; Takagi, Y.; Tsuda, H.; Kato, Y. Applying Nudge to Public Health Policy: Practical Examples and Tips for Designing Nudge Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA—U. S. Food & Drug Administration. Proposed Rule Food Labeling: Nutrient Content Claims; Definition of Term “Healthy”. 2022. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/29/2022-20975/food-labeling-nutrient-content-claims-definition-of-term-healthy (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Statista. Consumer Trends 2023: Food and Drink Edition: A Statista Trend Report on Future Food and Drink Trends; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Healthier Diets for Our Planet: New WHO/Europe Data Tool to Drive Innovative Country Policies. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/06-11-2023-healthier-diets-for-our-planet--new-who-europe-data-tool-to-drive-innovative-country-policies (accessed on 23 February 2024).

| Probiotic Nutrient Substance | Number of Claims |

|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | 157 |

| Bifidobacterium | 63 |

| Streptococcus | 12 |

| Combination of two or more probiotic bacteria strains | 86 |

| Others | 37 |

| Total probiotic claims | 355 |

| Country | Probiotics in Food | Probiotics in Food Supplement | Year of Specific Probiotic Statement |

|---|---|---|---|

| France [55] | considered as a “non-specific health claim” which is allowed if accompanied by a specific authorized claim related to the probiotic action | Allowed as a category name to characterize the nature of the substances used in the product | 2024 |

| Italy [56] | Requirements: 1. traditional use 2. safe 3. being active in the intestines in a specific quantity to multiply | Same as for food | 2018 |

| Spain [57] | Term ‘probiotic’ can be labeled on foods but not as a health claim until decided a uniform approach within the EU | Same as for food | 2020 |

| Country | Specific National Practice on Probiotics | Specific Provisions for Food Supplements |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | no response to the request | |

| Czech Republic | No | Not specified |

| Denmark | Yes, food supplements |

|

| Malta | no response to the request | |

| Netherlands | Yes, food supplements | Term ‘probiotic’ can be used as an indicator of a category in food supplements |

| Poland | Yes, food supplements |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jost, S.; Herzig, C.; Birringer, M. A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection. Foods 2025, 14, 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091651

Jost S, Herzig C, Birringer M. A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection. Foods. 2025; 14(9):1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091651

Chicago/Turabian StyleJost, Sonja, Christian Herzig, and Marc Birringer. 2025. "A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection" Foods 14, no. 9: 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091651

APA StyleJost, S., Herzig, C., & Birringer, M. (2025). A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection. Foods, 14(9), 1651. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091651