Reasons Behind (Un)Healthy Eating Among School-Age Children in Southern Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Food Selection

2.2. Formal Procedure

2.2.1. Children

2.2.2. Children’s Procedure

2.2.3. Parents’ Procedure

2.2.4. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Parents

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Children Clusters

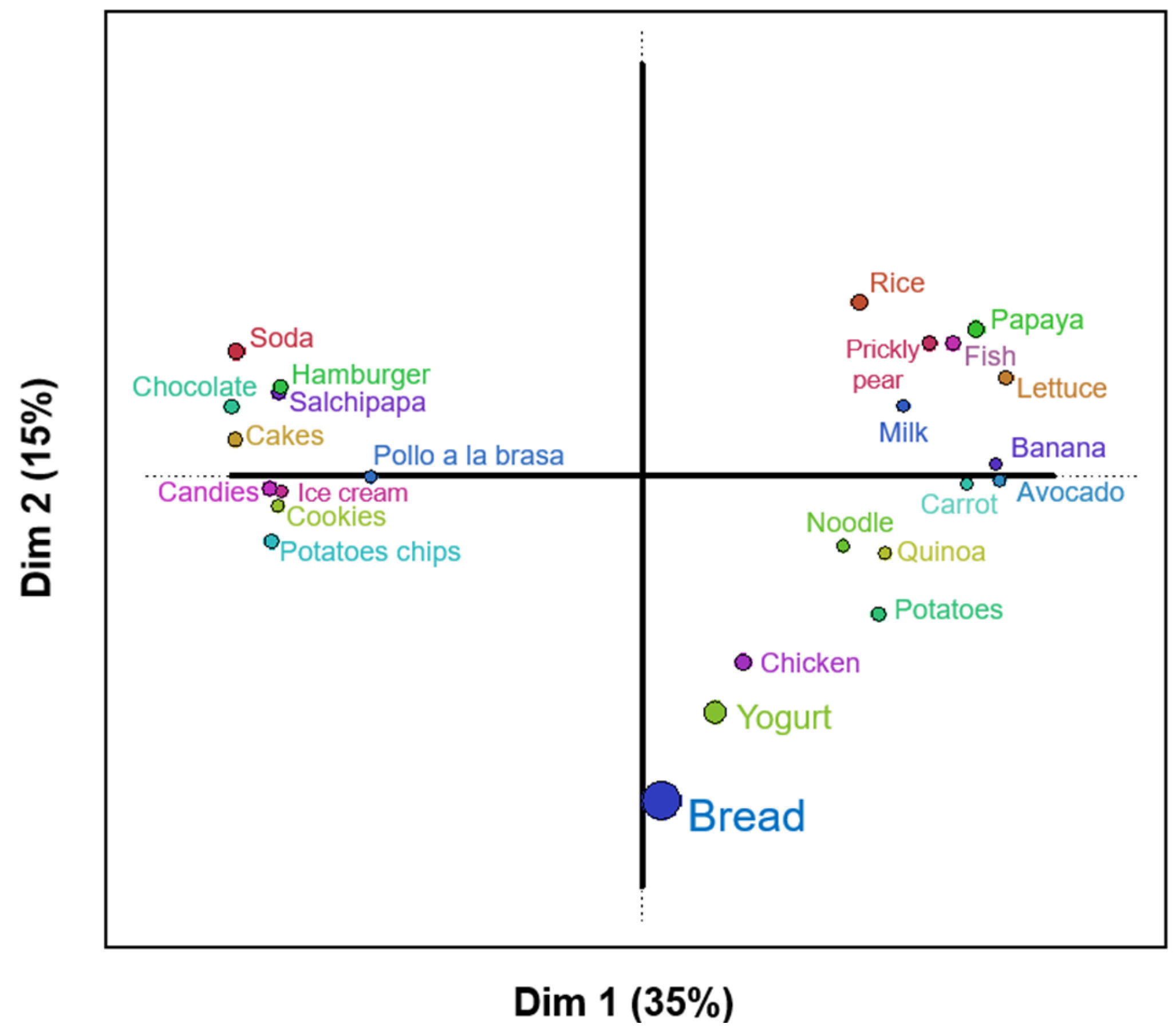

3.2. Classification of Foods

3.3. Free Listing of Parents

3.4. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Parents

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241510066 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Lobstein, T.; Baur, L.; Uauy, R. Obesity in children and young people: A crisis in public health. Obes. Rev. 2004, 5, 4–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebden, L.; Chey, T.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Lifestyle intervention for preventing weight gain in young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allman-Farinelli, M.A.; Chey, T.; Bauman, A.E.; Gill, T.; James, W.P.T. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian adults from 1990 to 2000. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Peng, W.; Xue, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Jia, P.; Wang, Y. Spatial–temporal trends in global childhood overweight and obesity from 1975 to 2030: A weight mean center and projection analysis of 191 countries. Glob. Health 2023, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INEI. Principales resultados Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F.; Chang, K.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Millett, C.; Vamos, E.P. Ultra-processed food consumption and type 2 diabetes incidence: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3608–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, F.; Chang, K.; Vamos, E.P.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Millett, C.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: A prospective cohort study of UK Biobank. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, K.; Aredo, V.; Rios-Mera, J.D.; Ambrosio, C.M.S.; Siche, R.; Saldaña, E. Chapter 13—Market needs and consumer’s preferences for healthier foods. In Strategies to Improve the Quality of Foods [Internet]; Lorenzo, J.M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biguzzi, C.; Schlich, P.; Lange, C. The impact of sugar and fat reduction on perception and liking of biscuits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 35, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, B.; Rios, Y.; Arranz, S.; Varela, P. Understanding children’s healthiness and hedonic perception of school meals via structured sorting. Appetite 2020, 144, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, R.K.; O’Brien, K.M.; Stacey, F.G.; Tzelepis, F.; Wyse, R.J.; Bartlem, K.M.; Sutherland, R.; James, E.L.; Barnes, C.; Wolfenden, L. Interventions for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in children aged five years and under. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD008552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeinstra, G.G.; Hoefnagels, F.A.; Meijboom, S.; Battjes-Fries, M.C.E. Implementation of four strategies in Dutch day-care centres to stimulate young children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite 2023, 181, 106378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez, A.L.; Vidal, L.; Antúnez, L.; Alcaire, F.; Varela, P.; Ares, G. Children’s reaction to sugar reduced dairy desserts in the context of the implementation of nutritional warning labels: An exploratory study. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S.; Issanchou, S. Children and food choice. In Understanding Consumers of Food Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, V.; Ting, C. Development of ideas about food and nutrition from preschool to university. Appetite 2010, 55, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faralla, V.; Savadori, L.; Mittone, L.; Novarese, M.; Ardizzone, A. Color and abundance: Influencing children’s food choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 109, 104918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, M.; Eum, W. Effects of Childhood Nutrition Education from School and Family on Eating Habits of Japanese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.S.N.; Chen, J.Y.; Ng, M.Y.C.; Yeung, M.H.Y.; Bedford, L.E.; Lam, C.L.K. How does the family influence adolescent eating habits in terms of knowledge, attitudes and practices? A global systematic review of qualitative studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatlow-Golden, M.; Hennessy, E.; Dean, M.; Hollywood, L. ‘Big, strong and healthy’. Young children’s identification of food and drink that contribute to healthy growth. Appetite 2013, 71, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.P. An apple a day keeps the doctor away: Children’s evaluative categories of food. Appetite 2007, 48, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Arrúa, A.; Antúnez, L.; Vidal, L.; Machín, L.; Martínez, J.; Curutchet, M.R.; Giménez, A. Influence of label design on children’s perception of two snack foods: Comparison of rating and choice-based conjoint analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, E.; Merlo, T.C.; Patinho, I.; Rios-Mera, J.D.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J.; Selani, M.M. Use of sensory science for the development of healthier processed meat products: A critical opinion. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E. New Developments in Sensory and Consumer Research with Children. In Methods in Consumer Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 321–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, T.C.; Saldaña, E.; Patinho, I.; Selani, M.M.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J. Free sorting task method to optimize the development of smoked bacon: A case study. In Sensory Analysis for the Development of Meat Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, S.; Lelièvre, M.; Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Sort and beer: Everything you wanted to know about the sorting task but did not dare to ask. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marque, C.; Motta, C.; Richard, T.J.C. Free sorting task of chocolate proteins bars: Pilot study and comparison between trained and untrained panelists. J. Sens. Stud. 2022, 37, e12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Salvador, A. Structured sorting using pictures as a way to study nutritional and hedonic perception in children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 37, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A.F.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. A downturn or a window of opportunity? How Danish and French parents perceive changes in healthy eating in the transition to parenthood. Appetite 2020, 150, 104658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud. Tablas Peruanas de Composición de Alimentos 2017; Ministerio Nacional de Salud: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E6D744D714B1FF09D5BCA3E74D53A185 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.J.; Vural, Y.; Berridge-Burley, N.; Butcher, C.; Cawley, E.; Gao, Z.; Sutcliffe, A.; Tinker, L.; Zeng, X.; Flynn, A.N.; et al. Evidence that carbohydrate-to-fat ratio and taste, but not energy density or NOVA level of processing, are determinants of food liking and food reward. Appetite 2024, 193, 107124. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666323025862 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, G.; Ferraris, D. Free listing: A method to gain initial insight of a food category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D.; Chollet, S.; Chrea, C. Analyzing assessors and products in sorting tasks: DISTATIS, theory and applications. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 627–640. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950329306001236 (accessed on 20 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.; Chin Fatt, C.R.; Abdi, H. An ExPosition of multivariate analysis with the singular value decomposition in R. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2014, 72, 176–189. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167947313004441 (accessed on 20 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Olsson, K.; González-Padilla, E.; Janzi, S.; Stubbendorff, A.; Borné, Y.; Ramne, S.; Ericson, U.; Sonestedt, E. Clusters of carbohydrate-rich foods and associations with type 2 diabetes incidence: A prospective cohort study. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Grain and Feed Annual (Issue April 2023); USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, J.; Haycraft, E.; Lytle, L.; Nicklaus, S.; Kok, F.J.; Merdji, M.; Fisberg, M.; Moreno, L.A.; Goulet, O.; Hughes, S.O. Nurturing Children’s Healthy Eating: Position statement. Appetite 2019, 137, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, R.; Viallon, V.; Fontvieille, E.; Peruchet-Noray, L.; Jansana, A.; Wagner, K.-H.; Kyrø, C.; Tjønneland, A.; Katzke, V.; Bajracharya, R.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: A multinational cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health—Eur. 2023, 35, 100771. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666776223001904 (accessed on 11 February 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filgueiras, A.R.; de Almeida, V.B.P.; Nogueira, P.C.K.; Domene, S.M.A.; da Silva, C.E.; Sesso, R.; Sawaya, A.L. Exploring the consumption of ultra-processed foods and its association with food addiction in overweight children. Appetite 2019, 135, 137–145. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666318310985 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, C.; Cui, L.; Fenfen, E.; Shang, W.; Wang, Z.; Song, G.; Yang, K.; Li, X. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella study of meta-analyses. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137460. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814623020782 (accessed on 12 September 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, J.P.M.; Costa, S.A.; Brandão, T.R.S.; Rocha, A. Food Consumption Determinants and Barriers for Healthy Eating at the Workplace—A University Setting. Foods 2021, 10, 695. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/4/695 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, L.; Flores-Barrantes, P.; Moreno, L.A.; Manios, Y.; Gonzalez-Gil, E.M. The Influence of Parental Dietary Behaviors and Practices on Children’s Eating Habits. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1138. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/4/1138 (accessed on 12 September 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenjin, K.; Sekine, M.; Yamada, M.; Tatsuse, T. Relationship Between Parental Lifestyle and Dietary Habits of Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogre, V.; Sefogah, P.E.; Adetunji, A.W.; Olalekan, O.O.; Gaa, P.K.; Anie, H.N.A.; Tayo, B. A school-based food and nutrition education intervention increases nutrition-related knowledge and fruit consumption among primary school children in northern Ghana. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPE. Comparativo Regional Educación. INCORE Perú. Instituto Peruano de Economía. 2024. Available online: https://incoreperu.pe/portal/index.php/ranking-regional (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Muñoz, A.; Fontalba-Navas, A.; Arrebola, J.P.; Larrea-Killinger, C. Trust and distrust in relation to food risks in Spain: An approach to the socio-cultural representations of pregnant and breastfeeding women through the technique of free listing. Appetite 2019, 142, 104365. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666319301217 (accessed on 21 December 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, B.; Nogueira, R.M.; Guimarães, K.R.L.S.L.d.Q.; Behrens, J.H. Sustainable diet from the urban Brazilian consumer perspective. Food Res. Int. 2019, 124, 206–212. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0963996918303831 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Neri, D.; Steele, E.M.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Zapata, M.E.; Rauber, F.; Marrón-Ponce, J.A.; Machado, P.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Andrade, G.C.; et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and dietary nutrient profiles associated with obesity: A multicountry study of children and adolescents. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13387. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/obr.13387 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirección General Parlamentaria. Carpeta Georeferencial: Región Moquegua Peru; Oficina de Gestión de la Información y Estadística: Lima, Peru, 2019; Available online: https://www.congreso.gob.pe/Docs/DGP/GestionInformacionEstadistica/files/carp_geo_2019/18_carpeta_georeferencial_moquegua_i.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Domínguez, P.R.; Gámiz, F.; Gil, M.; Moreno, H.; Zamora, R.M.; Gallo, M.; de Brugada, I. Providing choice increases children’s vegetable intake. Food Qual Prefer. 2013, 30, 108–113. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950329313000864 (accessed on 20 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L.A. Feeding Practices and Parenting: A Pathway to Child Health and Family Happiness. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74 (Suppl. S2), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales Santos, M.; Rosenthal, A.; Beatriz Araujo Martins, I.; de Alcantara, M.; Almeida Lima, M.; de Assis Carvalho, R.; Deliza, R. Exploring the role of the general interest in health on the perceptions of Healthy, Industrialized, and Ultra-processed foods among Brazilians. Food Res. Int. 2024, 181, 113992. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0963996924000620 (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Garg, R. The Impact of Packaged Food on Children’s Health: Strategies to Overcome. J. Client-Centered Nurs. Care. Iran Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S.M.; Alvarado, A.V.; Baker-Smith, C.M. Family Meals and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Young Children. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Ramsing, R.; Richardson, C.R.; Palmer, A. Barriers to healthy food access: Associations with household income and cooking behavior. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 298–305. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211335519300142 (accessed on 4 September 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puddephatt, J.-A.; Keenan, G.S.; Fielden, A.; Reaves, D.L.; Halford, J.C.; Hardman, C.A. ‘Eating to survive’: A qualitative analysis of factors influencing food choice and eating behaviour in a food-insecure population. Appetite. 2020, 147, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INEI. Principales Resultados Perú: Pobreza Monetaria; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y. Dietary Environment in Early Care and Education Settings and Young Children’s Eating Behavior: A Systematic Review of Literature. Am. J. Health Behav. 2022, 46, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varì, R.; Silenzi, A.; d’Amore, A.; Catena, A.; Masella, R.; Scazzocchio, B. MaestraNatura Reveals Its Effectiveness in Acquiring Nutritional Knowledge and Skills: Bridging the Gap between Girls and Boys from Primary School. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; O’Kane, C.; Issartel, J.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; McKernan, C.; Brooks, S.; O’Kane, N.; Crowe, W.; Murphy, B.; et al. Cook Like a Boss: An effective co-created multidisciplinary approach to improving children’s cooking competence. Appetite 2022, 168, 105727. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666321006346 (accessed on 12 December 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez, A.L.; Galler, M.; Vidal, L.; Varela, P.; Ares, G. Co-creation of a healthy dairy product with and for children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.L.; Sacco, S.J.; Fleming-Milici, F. TV exposure, attitudes about targeted food ads and brands, and unhealthy consumption by adolescents: Modeling a hierarchical relationship. Appetite 2022, 169, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Velázquez, A.L.; Vidal, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Varela, P. The role of food packaging on children’s diet: Insights for the design of comprehensive regulations to encourage healthier eating habits in childhood and beyond. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, S.J.; Ahern, S.M.; Remy, E.; Nicklaus, S.; Blundell, P.; Hetherington, M.M. Repetition counts: Repeated exposure increases intake of a novel vegetable in UK pre-school children compared to flavour–flavour and flavour–nutrient learning. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Healthy | Fairly Healthy | Unhealthy |

|---|---|---|

| Milk | Chicken | Ice cream |

| Fish | Potato | Potato chips |

| Carrot | Rice | Cake |

| Lettuce | Bread | Salchipapas (Peruvian dish consists of french fries and fried sausages) |

| Banana | Noodles | Hamburger |

| Papaya | Yogurt | Soda |

| Prickly pear | Pollo a la brasa (Peruvian baked chicken) | |

| Avocado | Biscuits | |

| Quinoa | Candies | |

| Chocolate |

| Variable | Moquegua Parents | Juliaca Parents |

|---|---|---|

| Number of parents (n) | 60 | 40 |

| Average age (years) | 38.5 ± 6.36 | 40 ± 7.07 |

Educational level

| 3% 7% 18% 64% 8% | 10% 28% 38% 22% 2% |

| Average monthly income (USD) | 700 ± 424.26 | 475 ± 194.45 |

| Average number of children | 2 ± 1.41 | 4.5 ± 1.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eduardo, K.; Velásquez, J.C.; Mayta-Hancco, J.; Rios-Mera, J.D.; Lozada-Urbano, M.; Saldaña, E. Reasons Behind (Un)Healthy Eating Among School-Age Children in Southern Peru. Foods 2025, 14, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030348

Eduardo K, Velásquez JC, Mayta-Hancco J, Rios-Mera JD, Lozada-Urbano M, Saldaña E. Reasons Behind (Un)Healthy Eating Among School-Age Children in Southern Peru. Foods. 2025; 14(3):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030348

Chicago/Turabian StyleEduardo, Karina, José Carlos Velásquez, Jhony Mayta-Hancco, Juan D. Rios-Mera, Michelle Lozada-Urbano, and Erick Saldaña. 2025. "Reasons Behind (Un)Healthy Eating Among School-Age Children in Southern Peru" Foods 14, no. 3: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030348

APA StyleEduardo, K., Velásquez, J. C., Mayta-Hancco, J., Rios-Mera, J. D., Lozada-Urbano, M., & Saldaña, E. (2025). Reasons Behind (Un)Healthy Eating Among School-Age Children in Southern Peru. Foods, 14(3), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030348