Construction and Textural Properties of Plant-Based Fat Analogues Based on a Soy Protein Isolate/Sodium Alginate Complex Coacervation System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

2.3. Determination of Oil Loading Rate of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

2.4. Determination of Condensation Yield of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

2.5. Preparation of Fat Analogues

2.6. Steaming Loss of Fat Analogues

2.7. Mechanical Properties of Fat Analogues

2.7.1. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

2.7.2. Puncture Test

2.7.3. Shear Test

2.8. Microscopic Structure

2.9. Sensory Evaluation Profiles of Fat Analogues

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

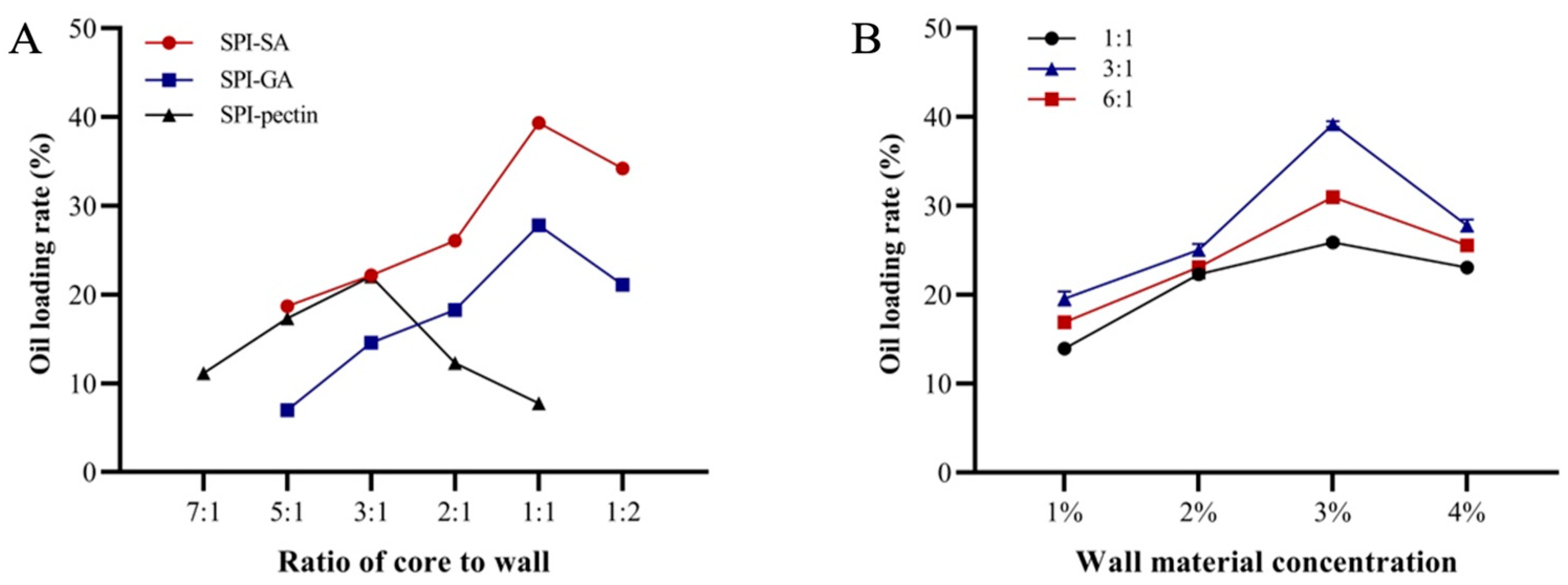

3.1.1. Effects of Wall Material Type, Proportion, Wall Material Concentration and Mass Ratio of Core to Wall on Oil Loading Rate of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

3.1.2. Effects of pH and Mixing Time on the Yield of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules

3.2. Preparation of Fat Analogues

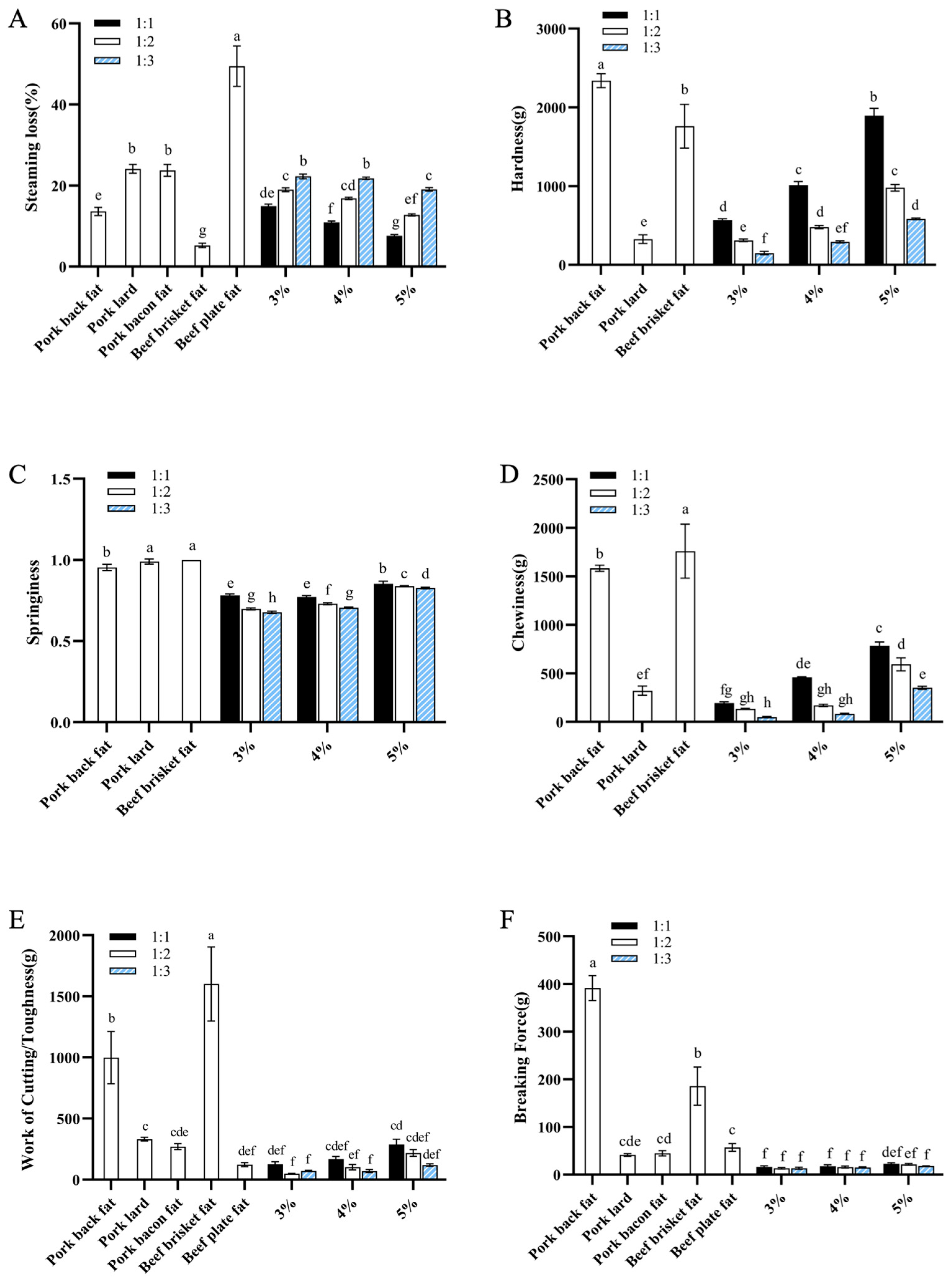

3.2.1. Effects of the Addition Amount of Oil-Loaded Microcapsules and Concentration of Curdlan on Steaming Loss and Mechanical Properties of Fat Analogues

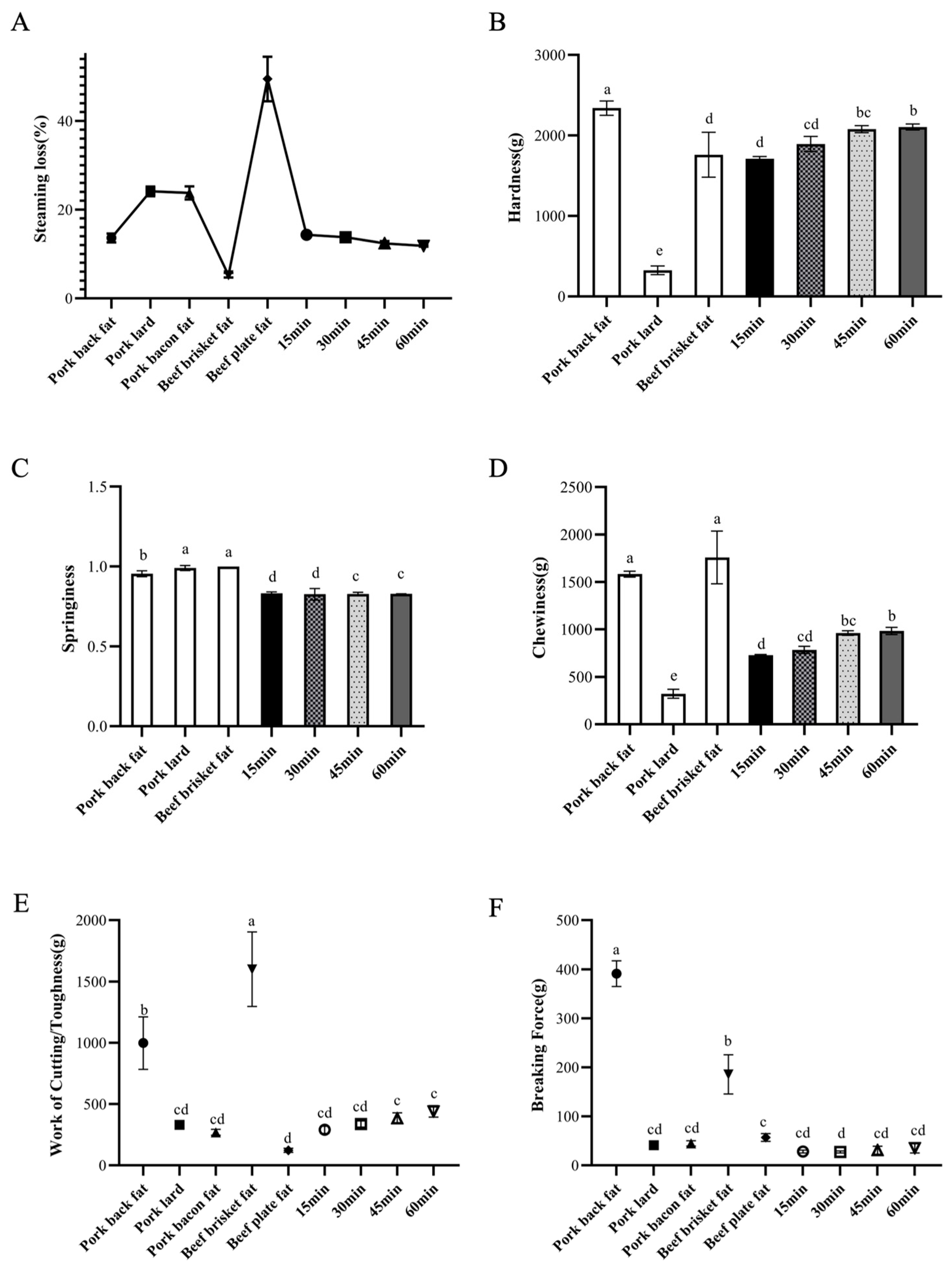

3.2.2. Effects of Different Heating Time on Steaming Loss and Mechanical Properties of Fat Analogues

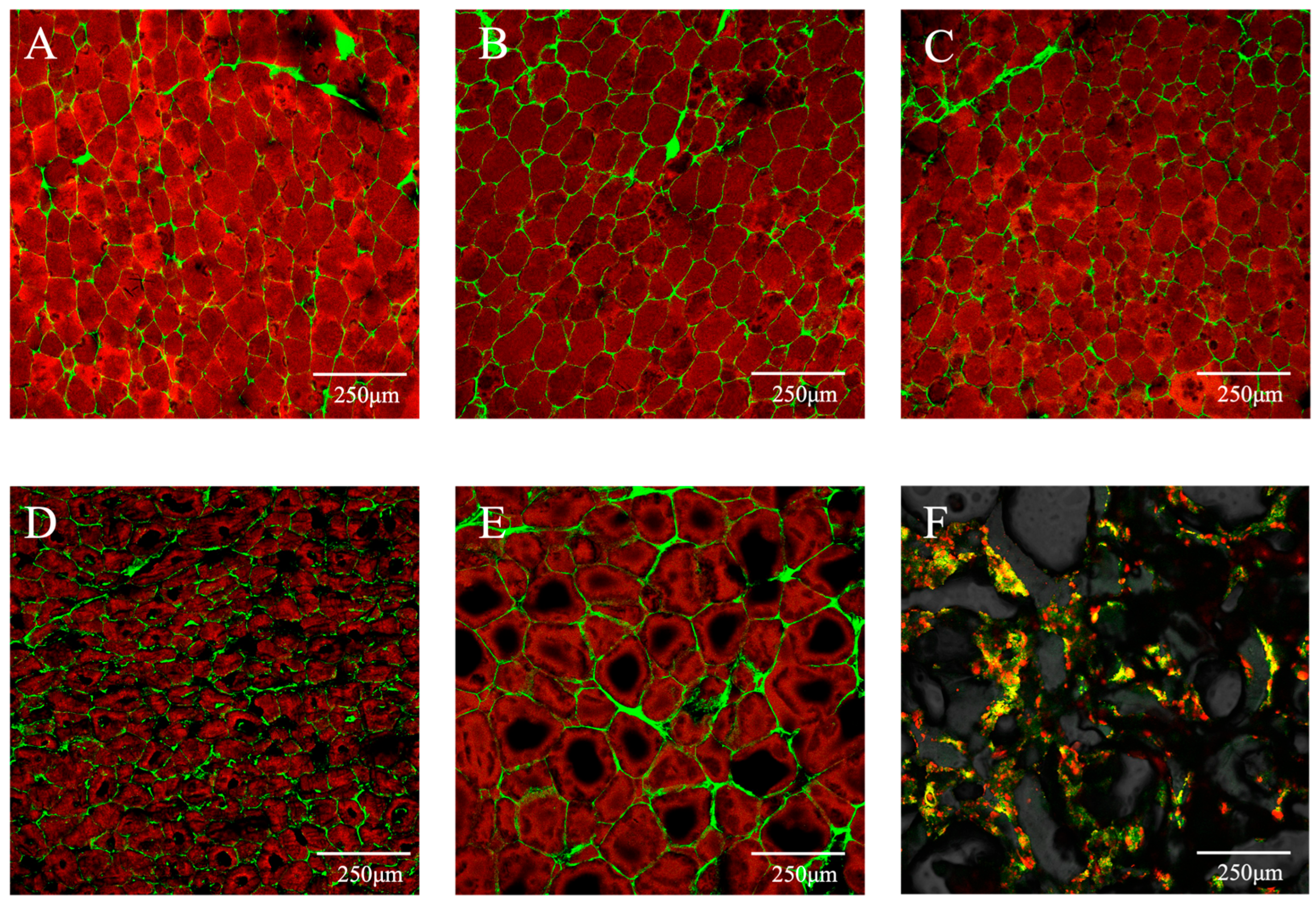

3.3. Microscopic Structure

3.4. Photographic Appearance and Sensory Evaluation Profiles of Fat Analogues

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBF | Protein-based fat Mimics |

| CBF | Carbohydrate-based fat Mimics |

| SPI | Soy protein isolates |

| SA | Sodium alginate |

| GA | Gum acacia |

| CUD | Curdlan |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscope |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

References

- Jimenez-Cplmenero, F.; Cofrades, S.; Herrero, A.M. Konjac gel fat analogue for use in meat products: Compari-son with pork fats. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 26, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Sans, P.; JVan Loo, E. Challenges and prospects for consumer acceptance of cultured meat. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cao, T.; Tang, Q. Research progress on low-calorie fat mimetics based on carbohydrates. J. Chin. Cereals Oils Assoc. 2021, 36, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Eskandari, M.H.; Davoudi, Z. Application and functions of fat replacers in low-fat ice cream: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.T.; Zhi, H.; Shen, X.Y.; Liu, D.H.; Ye, X.Q. Research progress of fat substitutes in baking industry. Food Ferment. Ind. 2020, 46, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, J.; Blach, C.; Terjung, N.; Gibis, M.; Weiss, J. Influence of protein content on plant-based emulsified and crosslinked fat crystal networks to mimic animal fat tissue. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 106, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Emulsion gels: The structuring of soft solids with protein-stabilized oil droplets. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 28, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.X.; Cui, L.J.; Meng, Z. Oleogels/emulsion gels as novel saturated fat replacers in meat products: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, O.; Murray, B.; Sarkar, A. Emulsion microgel particles: Novel encapsulation strategy for lipophilic molecule. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Q.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.X. Application of emulsion gels as fat substitutes in meat products. Foods 2022, 11, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Co, E.D.; Marangoni, A.G. Organogels: An alternative edible oilstructuring method. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 749–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernetti, M.; Van Malssen, K.F.; Flöter, E.; Bot, A. Structuring of edible oils by alternatives to crystalline fat. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 12, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-colmenero, F.; Salcedo-sandoval, L.; Bou, R.; Cofrades, S.; Herrero, A.M.; Ruiz-Capillas, C. Novel applications of oil-structuring methods as a strategy to improve the fat content of meat products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 44, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Dewettinck, K. Edible oil structuring: An overview and recent updates. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.F.; Meng, Z. Protein-based oleogels: A comprehensive review of oleogelators, preparation, stabilization mechanisms, and applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 172, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehany, T.; Zannou, O.; Oussou, K.F.; Chabi, I.B.; Tahergorabi, R. Innovative oleogels: Developing sustainable bioactive delivery systems for healthier foods production. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.M.; Barbut, S.; Marangoni, A.G. Edible oleogels for the oral delivery of lipid soluble molecules: Composition and structural design considerations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, D.L.; Yu, K.F.; Chen, H. Transcriptome landscape of porcine intramuscular adipocytes during differentiation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6317–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, S.; Weigert, J.; Neumeier, M.; Wanninger, J.; Schaffler, A.; Luchner, A.; Schnitzbauer, A.A.; Aslanidis, C.; Buechler, C. Low-abundant adiponectin receptors in visceral adipose tissue of humans and rats are further reduced in diabetic animals. Arch. Med. Res. 2010, 41, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundquist, P.K.; Shivaiah, K.K.; Espinoza-Corral, R. Lipid droplets throughout the evolutionary tree. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020, 78, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Yang, H. Study on Encapsulation of Tea Tree Oil/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex by Complex Coacervation. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 48, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.H.; Liu, G.Z.; Hao, L.; Qin, L.Y.; Yang, Z.W. Optimization of Complex Coacervation Process for Preparation of Sophora Japonica Rutin Microcapsules. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 46, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.J. Study on the Preparation of Plant Essential Oil Microcapsules by Complex Coacervation and their Antibacterial Properties. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, F.; Haghighi Asl, A.; Rafe, A. Characterization of caseinate-pectin complex coacervates as a carrier for delivery and controlled-release of saffron extract. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B. Optimization of Preparation Process and Quality Analysis of Nitraria Seed Oil Microcapsules. Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 47, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheeder, M.R.L.; Casutt, M.M.; Roulin, M.; Escher, F.; Dufey, P.A.; Kreuzer, M. Fatty acid composition, cooking loss and texture of beef patties from meat of bulls fed different fats. Meat Sci. 2001, 58, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shan, J.; Han, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. Optimization of Fish Quality by Evaluation of Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen (TVB-N) and Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) by Near-Infrared (NIR) Hyperspectral Imaging. Anal. Lett. 2019, 52, 1845–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.R.; Rafe, A.; Yeganehzad, S. Textural, mechanical, and microstructural properties of restructured pimiento alginate-guar gels. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, J.; Verplanken, K.; Vercruysse, V.; Ampe, B.; Aluwe, M.; Vanhaecke, L. Sensory evaluation of boar meat products by trained experts. Food Chem. 2020, 237, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8586:2023; Sensory Analysis—Selection and Training of Sensory Assessors. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Czapalay, E.; Marangoni, A. Functional properties of oleogels and emulsion gels as adipose tissue mimetics. Trend Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.Y.; Hu, R.S.; Tang, Y.M.; Dong, W.J.; Zhang, Z.Z. Microencapsulation of green coffee oil by complex coacervation of soy protein isolate, sodium casinate and polysaccharides: Physicochemical properties, structural characterisation, and oxidation stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.R.; Zhang, Z.F.; Shao, J.S.; Wu, X.H.; Zhu, B.B.; He, X.Y.; Wang, H.W.; Zhang, Y.T. Sodium alginate-mediated interfacial structuring in soy protein-quercetin composite emulsions: A synergistic strategy for encapsulation and bioavailability enhancement of lipophilic bioactives. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, A.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovacs, B. Protein-polysaccharide complexes and conjugates: Structural modifications and interactions under diverse treatments. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.H.; Dong, J.L.; Liu, H. Improved viability of probiotics encapsulated in soybean protein isolate matrix microcapsules by coacervation and cross-linking modification. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 138, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, F.; Haghighi Asl, A.; Rafe, A. Phase separation and formation of sodium caseinate/pectin complex coacervates: Effects of pH on the complexation. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Mao, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Ye, S. Properties of soybean protein isolate/curdlan based emulsion gel for fat analogue: Comparison with pork backfat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Qin, X. Physicochemical properties and intermolecular interactions of a novel diacylglycerol oil oleogel made with ethyl cellulose as affected by γ-oryzanol. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 138, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Song, L.J.; Huang, X.Q.; Cui, W.M.; Wang, F. Application of texture analyzer in food analysis and testing. Agric. Prod. Process. 2017, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Zou, T.; Zheng, B.D.; Tan, B.K.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.L. Study on the mechanism of soy protein isolate and curdlan enhances quality of reduced salt myofibrillar protein gel: Insights into water distribution, gel characteristics, and sodium release. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 172, 111884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, H.; McClements, D.J. Utilization of emulsion technology to create plant-based adipose tissue analogs: Soy-based high internal phase emulsions. Food Struct. 2022, 33, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijarnprecha, K.; Gregson, C.; Sillick, M.; Fuhrmann, P.; Sonwai, S.; Rousseau, D. Temperature-dependent properties of fat in adipose tissue from pork, beef and lamb. Part 1: Microstructural, thermal, and spectroscopic characterisation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7112–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, N.D.; Acevedo, N.C.; Cho, K.; Zuber-McQuillen, E.A.; Carvajal, Y.B.; Tarté, R. Novel biphasic gels can mimic and replace animal fat in fully-cooked coarse-ground sausage. Meat Sci. 2022, 194, 108984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, C.; Campanella, O.H. A plant-based animal fat analog produced by an emulsion gel of alginate and pea protein. Gels 2023, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, Y.; Liang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, M.; He, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J. Construction and Textural Properties of Plant-Based Fat Analogues Based on a Soy Protein Isolate/Sodium Alginate Complex Coacervation System. Foods 2025, 14, 4355. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244355

Tu Y, Liang G, Wang Z, Zeng M, He Z, Chen Q, Chen J. Construction and Textural Properties of Plant-Based Fat Analogues Based on a Soy Protein Isolate/Sodium Alginate Complex Coacervation System. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4355. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244355

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Yilin, Guijiang Liang, Zhaojun Wang, Maomao Zeng, Zhiyong He, Qiuming Chen, and Jie Chen. 2025. "Construction and Textural Properties of Plant-Based Fat Analogues Based on a Soy Protein Isolate/Sodium Alginate Complex Coacervation System" Foods 14, no. 24: 4355. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244355

APA StyleTu, Y., Liang, G., Wang, Z., Zeng, M., He, Z., Chen, Q., & Chen, J. (2025). Construction and Textural Properties of Plant-Based Fat Analogues Based on a Soy Protein Isolate/Sodium Alginate Complex Coacervation System. Foods, 14(24), 4355. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244355