Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Fermented Dairy Products from the Croatian Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

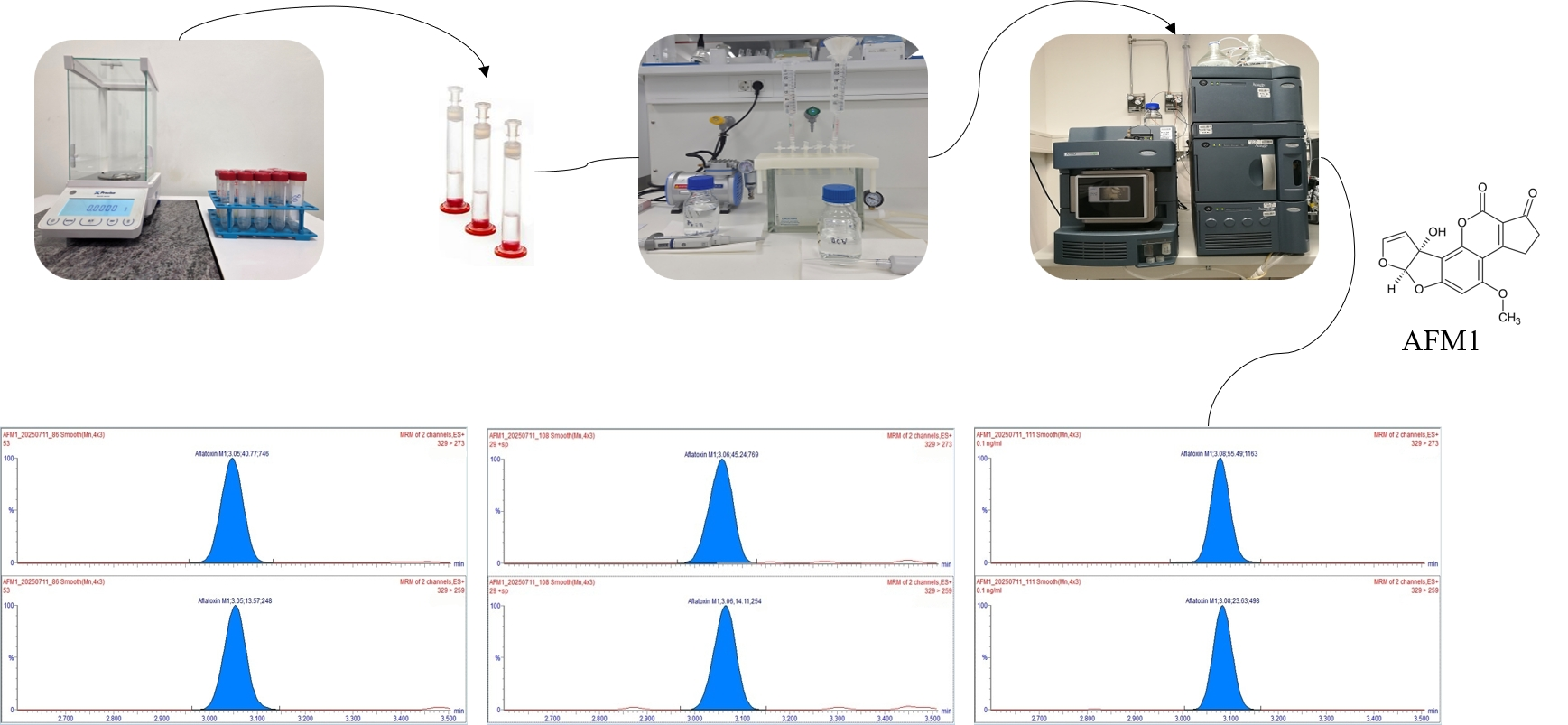

2.2. Chemicals, Equipment, and Analytical Determination

2.2.1. Chemicals, Equipment and Sample Preparation

2.2.2. Analytical Determination

2.3. Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

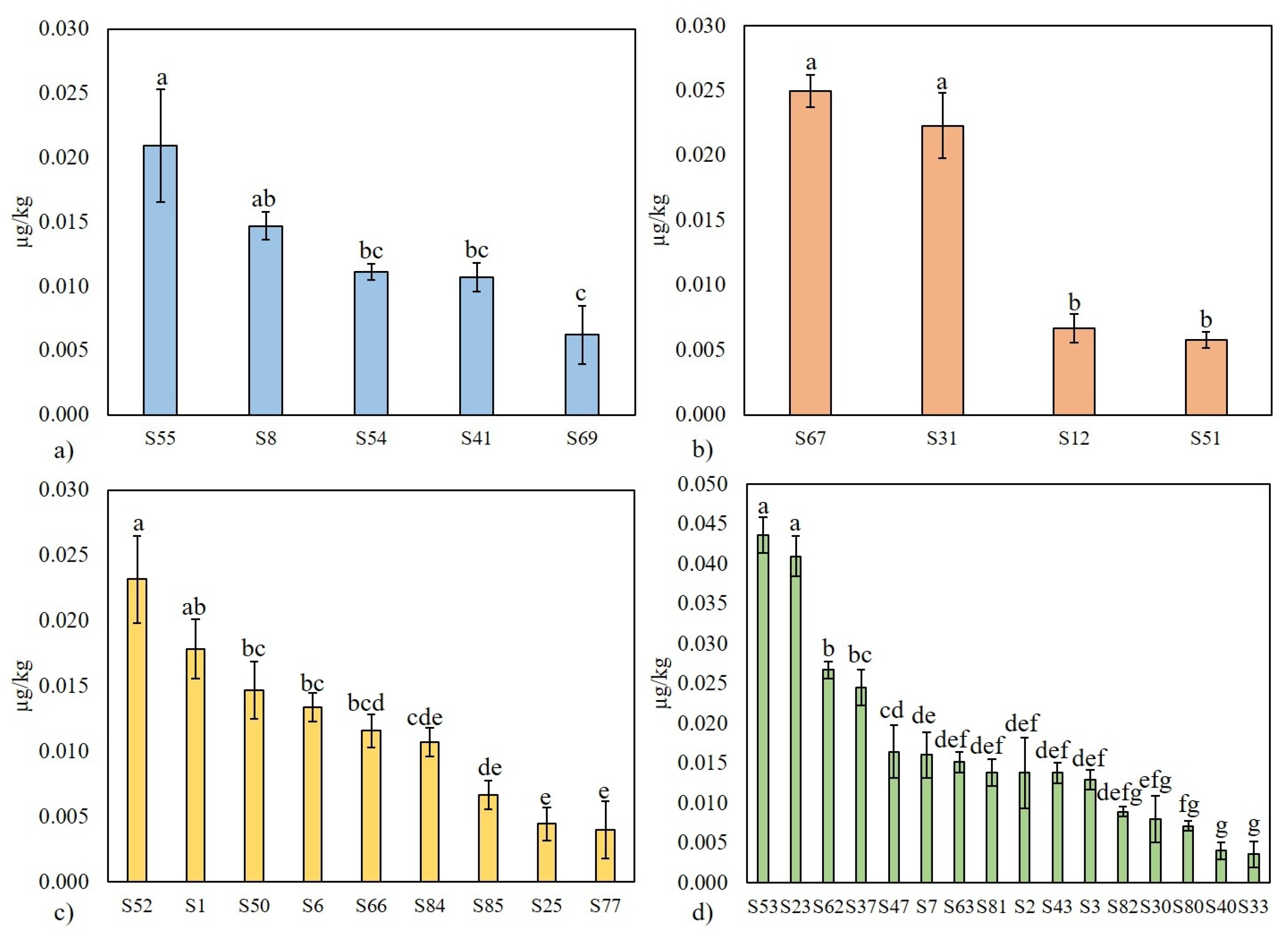

3.1. Occurrence of AFM1 in Fermented Dairy Products

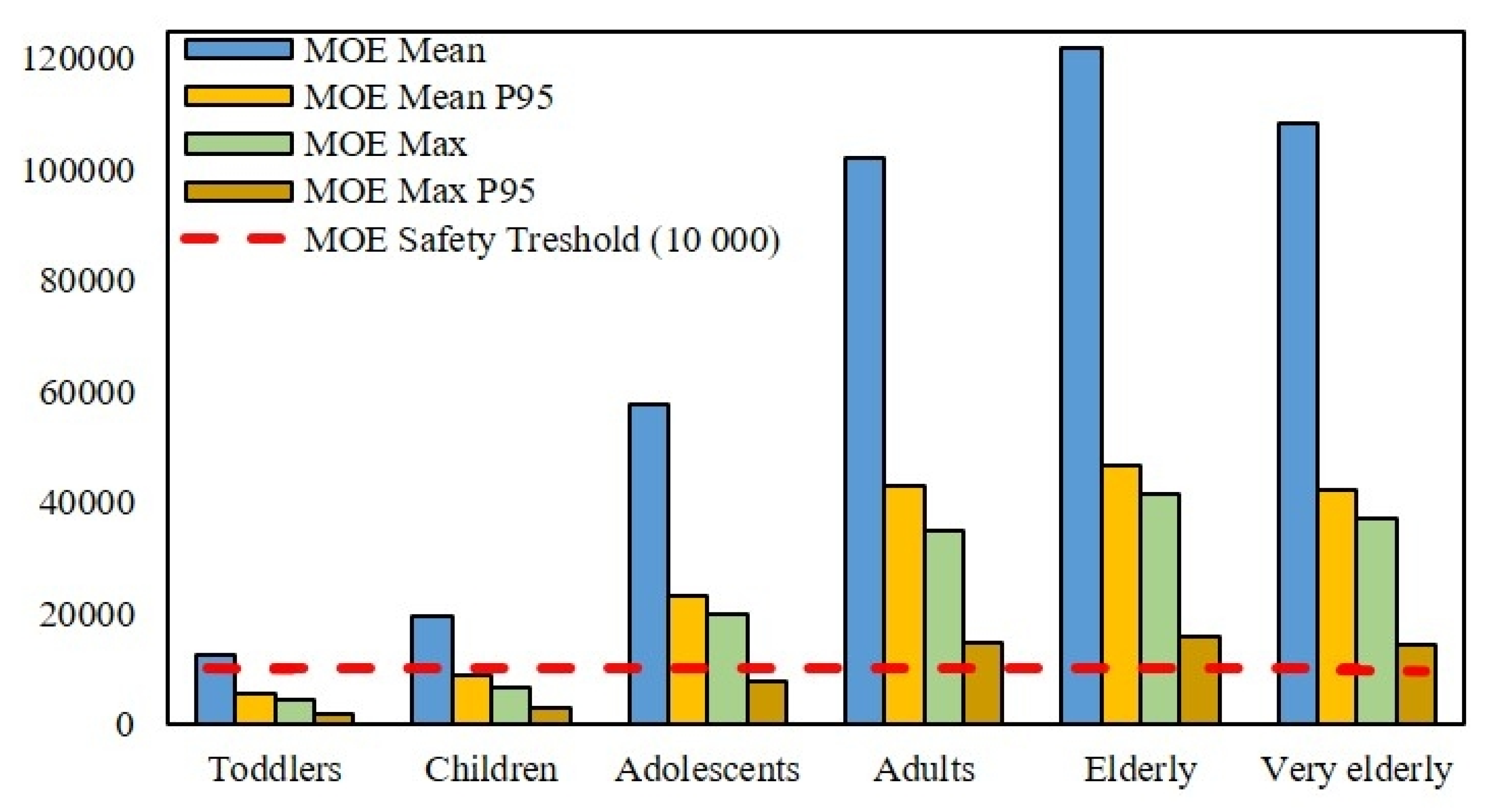

3.2. Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment for Different Age Groups

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malissiova, E.; Tsinopoulou, G.; Gerovasileiou, E.S.; Meleti, E.; Soultani, G.; Koureas, M.; Maisoglou, I.; Manouras, A. A 20-Year Data Review on the Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products in Mediterranean Countries—Current Situation and Exposure Risks. Dairy 2024, 5, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunović, M.; Kovač Tomas, M.; Šarić, A.; Lučan, M.; Kovač, T. Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products—A Mini Review. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 14, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). Aflatoxins. Chemical Agents and Related Occupations. A Review of Human Carcinogens; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Lyon, France, 2012; Volume 100F, pp. 225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, J.; Radić, B.; Lešić, T.; Anić, M.; Jovanov, P.; Šarić, B.; Pleadin, J. Climate Change and Mycotoxins Trends in Serbia and Croatia: A 15-Year Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L135, 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bilandžić, N.; Varga, I.; Čalopek, B.; Solomun Kolanović, B.; Varenina, I.; Đokić, M.; Sedak, M.; Cvetnić, L.; Pavliček, D.; Končurat, A. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 over Three Years in Raw Milk from Croatia: Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization in Consumers of Different Ages and Genders. Foods 2025, 14, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilandžić, N.; Varga, I.; Varenina, I.; Solomun Kolanović, B.; Božić Luburić, Ð.; Ðokić, M.; Sedak, M.; Cvetnić, L.; Cvetnić, Ž. Seasonal Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk during a Five-Year Period in Croatia: Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Foods 2022, 11, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandžić, N.; Božić, Đ.; Đokić, M.; Sedak, M.; Solomun Kolanović, B.; Varenina, I.; Tanković, S.; Cvetnić, Ž. Seasonal Effect on Aflatoxin M1 Contamination in Raw and UHT Milk from Croatia. Food Control 2014, 40, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants (CONTAM); Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.C.; et al. Scientific Opinion—Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins in Food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; Maggiore, A.; Afonso, A.; Barrucci, F.; De Sanctis, G. Climate Change as a Driver of Emerging Risks for Food and Feed Safety, Plant, Animal Health and Nutritional Quality. EFSA Support. Publ. 2020, 17, 1881E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Climate Change: Unpacking the Burden on Food Safety; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač Tomas, M.; Jurčević Šangut, I. New Insights into Mycotoxin Contamination, Detection, and Mitigation in Food and Feed Systems. Toxins 2025, 17, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyedele, O.A.; Akinyemi, M.O.; Kovač, T.; Eze, U.A.; Ezekiel, C.N. Food Safety in the Face of Climate Change. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 12, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, J.; Anić, M.; Radić, B.; Zadravec, M.; Janić Hajnal, E.; Pleadin, J. Climate Change—A Global Threat Resulting in Increasing Mycotoxin Occurrence. Foods 2023, 12, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Rossi, V.; Giorni, P.; Pietri, A.; Gualla, A.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Booij, C.J.H.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.; Miglietta, F.; et al. Modelling, Predicting and Mapping the Emergence of Aflatoxins in Cereals in the EU Due to Climate Change. EFSA Support. Publ. 2012, 9, 223E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Toscano, P.; Van Der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Moretti, A.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Brera, C.; Rortais, A.; Goumperis, T.; Robinson, T. Aflatoxin B1 Contamination in Maize in Europe Increases Due to Climate Change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 401/2006 laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of the levels of mycotoxins in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L70, 12–34. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Decision of 14 August 2002 implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC concerning the performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2002, L221, 8–36. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Food Consumption Statistics for FoodEx2: Level 1. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/microstrategy/foodex2-level-1 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- de Souza, C.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Fernandes Oliveira, C.A. The Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Industrial and Traditional Fermented Milk: A Systematic Review Study. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2021, 33, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaris, A.; Roussi, V.; Koidis, P.A.; Botsoglou, N.A. Distribution and Stability of Aflatoxin M1 during Production and Storage of Yoghurt. Food Addit. Contam. 2002, 19, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barukčić, I.; Bilandžić, N.; Markov, K.; Jakopović, K.L.; Božanić, R. Reduction in Aflatoxin M1 Concentration during Production and Storage of Selected Fermented Milks. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2018, 71, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradkhani, F.; Sekhavatizadeh, S.S.; Marhamatizadeh, M.H.; Ghasemi, M. Biodetoxification of Aflatoxin M1 in Artificially Contaminated Fermented Milk, Fermented Dairy Drink and Yogurt Using Lactobacillus Strains and Its Effects on Physicochemical Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, 70175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahromi, A.S.; Jokar, M.; Abdous, A.; Rabiee, M.H.; Biglo, F.H.B.; Rahmanian, V. Prevalence and Concentration of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Int. Health 2025, 17, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golenja, J.; Mezga, I.; Milly, K.; Rot, T.; Kovač Tomas, M. Pojavnost Aflatoksina M1 u Mlijeku s Tržišta Republike Hrvatske (conference work). In Knjiga Sažetaka SANITAS 2023, Proceedings of the Studentski Kongres Zaštite Zdravlja, Rijeka, Croatia, 16–18 March 2023; Manin, L., Dobrić, D., Turkalj, R., Mudrovčić, K., Škorić, K., Eds.; Medicinski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Rijeci: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- DHMZ (Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service). Odabrana Poglavlja Osmog Nacionalnog Izvješća Republike Hrvatske prema Okvirnoj Konvenciji Ujedinjenih Naroda o Promjeni Klime; DHMZ: Zagreb, Croatia, 2023; Available online: https://klima.hr/razno/publikacije/8NIKP_DHMZ.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kovač, M.; Bulaić, M.; Nevistić, A.; Rot, T.; Babić, J.; Panjičko, M.; Kovač, T.; Šarkanj, B. Regulated Mycotoxin Occurrence and Co-Occurrence in Croatian Cereals. Toxins 2022, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleadin, J.; Zadravec, M.; Lešić, T.; Frece, J.; Markov, K.; Vasilj, V. Climate Change—A Potential Threat for Increasing Occurrences of Mycotoxins. Vet. Stanica 2020, 51, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, V.; Magan, N. Environmental Conditions Affecting Mycotoxins. In Fungal Growth in Stored Grains; Magan, N., Olsen, M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Soston, UK, 2004; pp. 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- DHMZ (Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service). Climate Reports; DHMZ: Zagreb, Croatia, 2025; Available online: https://meteo.hr/klima_e.php?section=klima_pracenje¶m=ocjena (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Udovicki, B.; Djekic, I.; Kalogianni, E.P.; Rajkovic, A. Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization of Aflatoxin M1 Intake through Consumption of Milk and Yoghurt by Student Population in Serbia and Greece. Toxins 2019, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, R.; Nejati, R.; Sayadi, M.; Loghmani, A.; Dehghan, A.; Nematollahi, A. Health Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 Exposure through Traditional Dairy Products in Fasa, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 197, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Bedi, J.S.; Dhaka, P.; Vijay, D.; Aulakh, R.S. Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization of Aflatoxin M1 through Consumption of Market Milk and Milk Products in Ludhiana, Punjab. Food Control 2021, 126, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebib, H.; Abate, D.; Woldegiorgis, A.Z. Exposure and Health Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk and Cottage Cheese in Adults in Ethiopia. Foods 2023, 12, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipoyan, D.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Beglaryan, M.; Mantovani, A. Risk Assessment of AFM1 in Raw Milk and Dairy Products Produced in Armenia, a Caucasus Region Country: A Pilot Study. Foods 2024, 13, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Ao, W.; Zhou, X.; Yang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, C.; Qiu, Y. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Three Types of Milk from Xinjiang, China, and the Risk of Exposure for Milk Consumers in Different Age-Sex Groups. Foods 2022, 11, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serraino, A.; Bonilauri, P.; Kerekes, K.; Farkas, Z.; Giacometti, F.; Canever, A.; Zambrini, A.V.; Ambrus, Á. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk Marketed in Italy: Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbial Culture | n * | Mean ± SD µg/kg | Occurrence % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesophilic bacteria | 10 | 0.013 ± 0.005 | 50.0 |

| Thermophilic bacteria | 48 | 0.017 ± 0.012 | 33.3 |

| Probiotic bacteria | 10 | 0.015 ± 0.010 | 40.0 |

| Kefir grains | 13 | 0.012 ± 0.006 | 69.2 |

| Product Origin * | n | Mean ± SD µg/kg | Median µg/kg | Occurrence % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | 49 | 0.015 ± 0.010 | 0.014 | 55.1 a |

| Non-Croatia | 32 | 0.012 ± 0.007 | 0.012 | 21.9 b |

| Age Category | Data Type | Consumption g/kg bw/day | 0.015 ng/kg AFM1 a | 0.044 ng/kg AFM1 b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDI | HI | EDI | HI | |||

| Toddlers 1–3 | EFSA Mean c | 21.11 | 0.32 | 1.58 | 0.93 | 4.64 |

| EFSA P95 | 49.24 | 0.74 | 3.69 | 2.17 | 10.83 | |

| Calculated d | 8.33 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.83 | |

| Children 3–10 | EFSA Mean | 13.77 | 0.21 | 1.03 | 0.61 | 3.03 |

| EFSA P95 | 29.98 | 0.45 | 2.25 | 1.32 | 6.60 | |

| Calculated | 3.83 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.84 | |

| Adolescents 10–18 | EFSA Mean | 4.62 | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 1.02 |

| EFSA P95 | 11.56 | 0.17 | 0.87 | 0.51 | 2.54 | |

| Calculated | 1.90 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.42 | |

| Adults 18–65 | EFSA Mean | 2.61 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.57 |

| EFSA P95 | 6.22 | 0.09 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 1.37 | |

| Calculated | 1.43 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.31 | |

| Elderly 65–75 | EFSA Mean | 2.19 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| EFSA P95 | 5.72 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 1.26 | |

| Calculated | 1.43 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.31 | |

| Very elderly >75 | EFSA Mean | 2.46 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.54 |

| EFSA P95 | 6.29 | 0.09 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 1.38 | |

| Calculated | 1.43 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.31 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovač Tomas, M.; Rot, T.; Arnautović, L.; Lenardić Bedenik, M.; Jurčević Šangut, I. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Fermented Dairy Products from the Croatian Market. Foods 2025, 14, 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244354

Kovač Tomas M, Rot T, Arnautović L, Lenardić Bedenik M, Jurčević Šangut I. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Fermented Dairy Products from the Croatian Market. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244354

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovač Tomas, Marija, Tomislav Rot, Lara Arnautović, Mirjana Lenardić Bedenik, and Iva Jurčević Šangut. 2025. "Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Fermented Dairy Products from the Croatian Market" Foods 14, no. 24: 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244354

APA StyleKovač Tomas, M., Rot, T., Arnautović, L., Lenardić Bedenik, M., & Jurčević Šangut, I. (2025). Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Fermented Dairy Products from the Croatian Market. Foods, 14(24), 4354. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244354