Bioprotective Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici L1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HG1-1 in Harbin Red Sausage Under Vacuum Packaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Preparation

2.2. Preparation of Harbin Red Sausages

2.3. Inoculation of Bacteria

2.4. Packaging and Storage

2.5. Bacterial Enumeration

2.6. Physicochemical Analysis

2.7. Electronic Nose

2.8. Electronic Tongue

2.9. Sensory Evaluation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

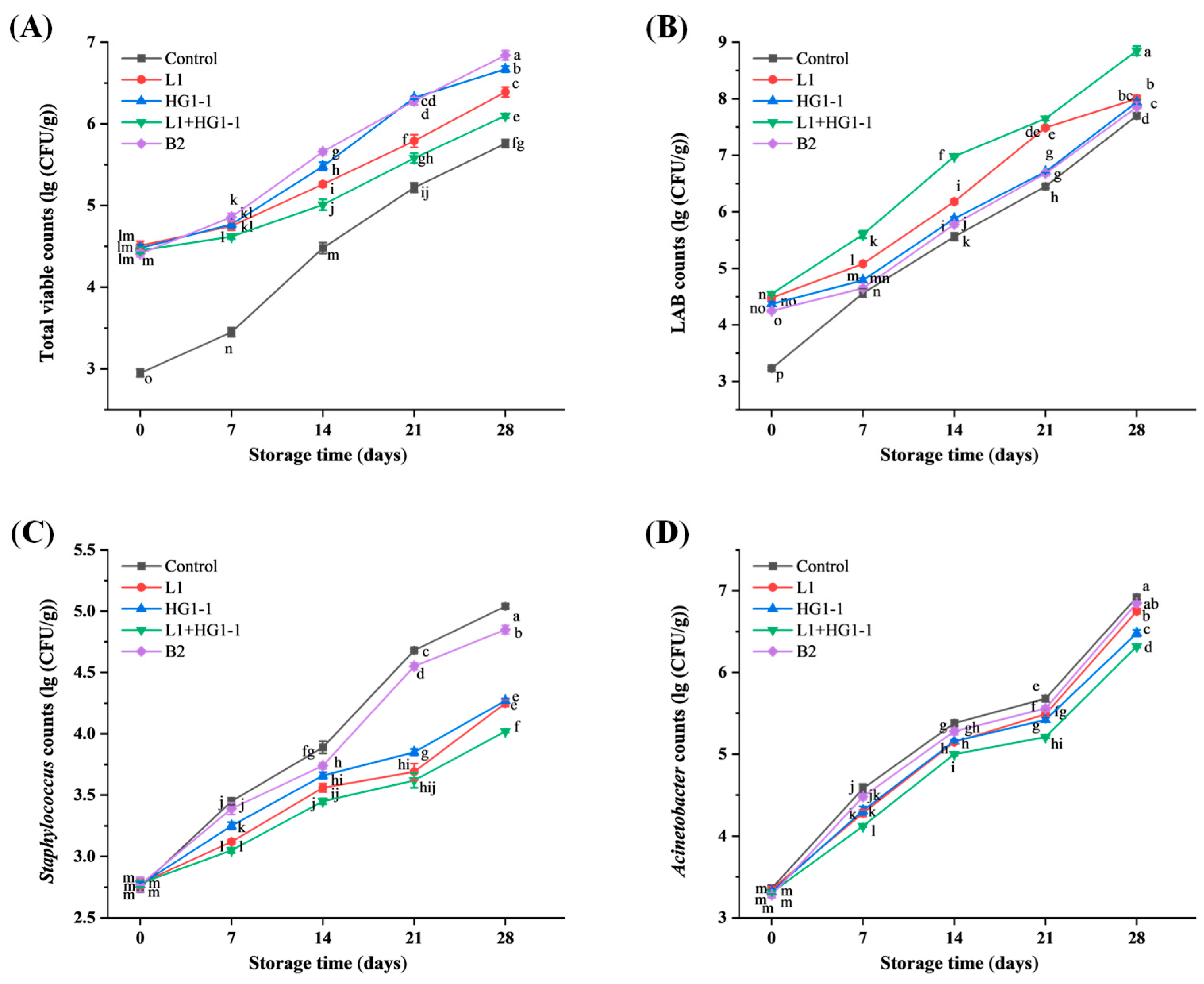

3.1. Bacterial Analysis

3.1.1. Total Viable Counts

3.1.2. Lactic Acid Bacteria Counts

3.1.3. Staphylococcus Counts

3.1.4. Acinetobacter Counts

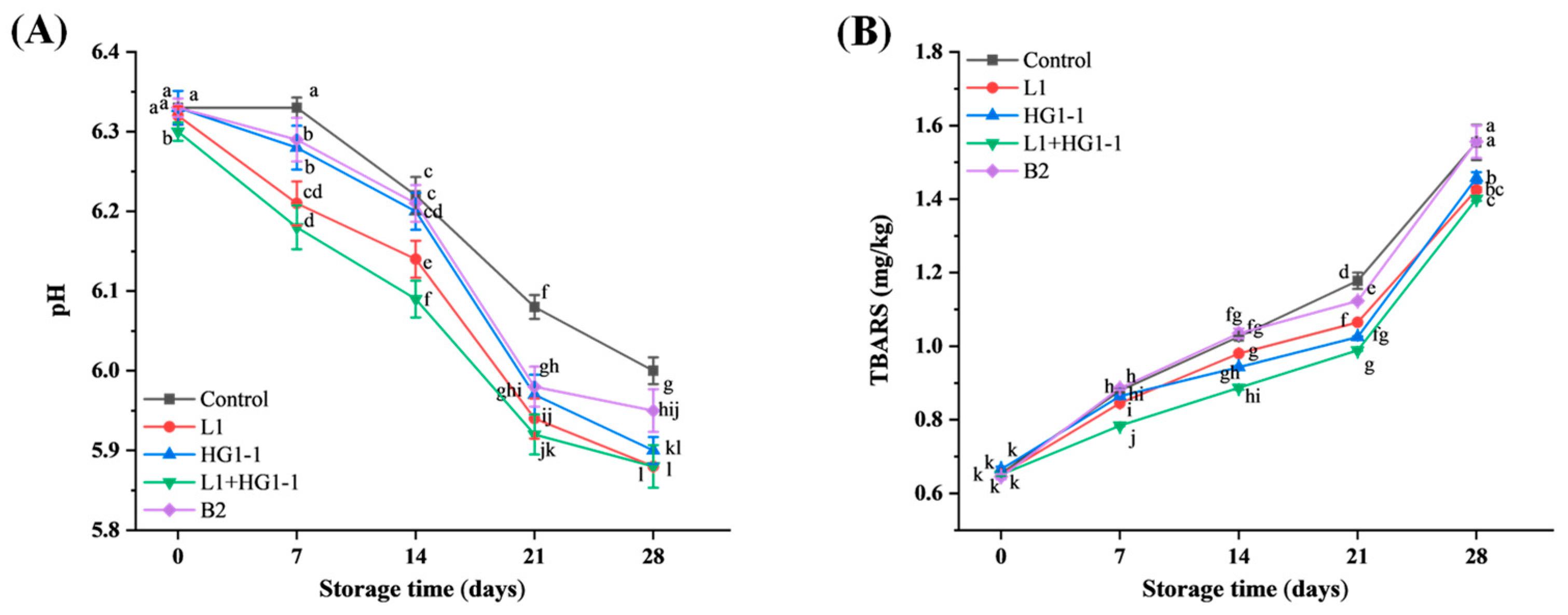

3.2. pH

3.3. Lipid Oxidation

3.4. Moisture Content and Water Activity

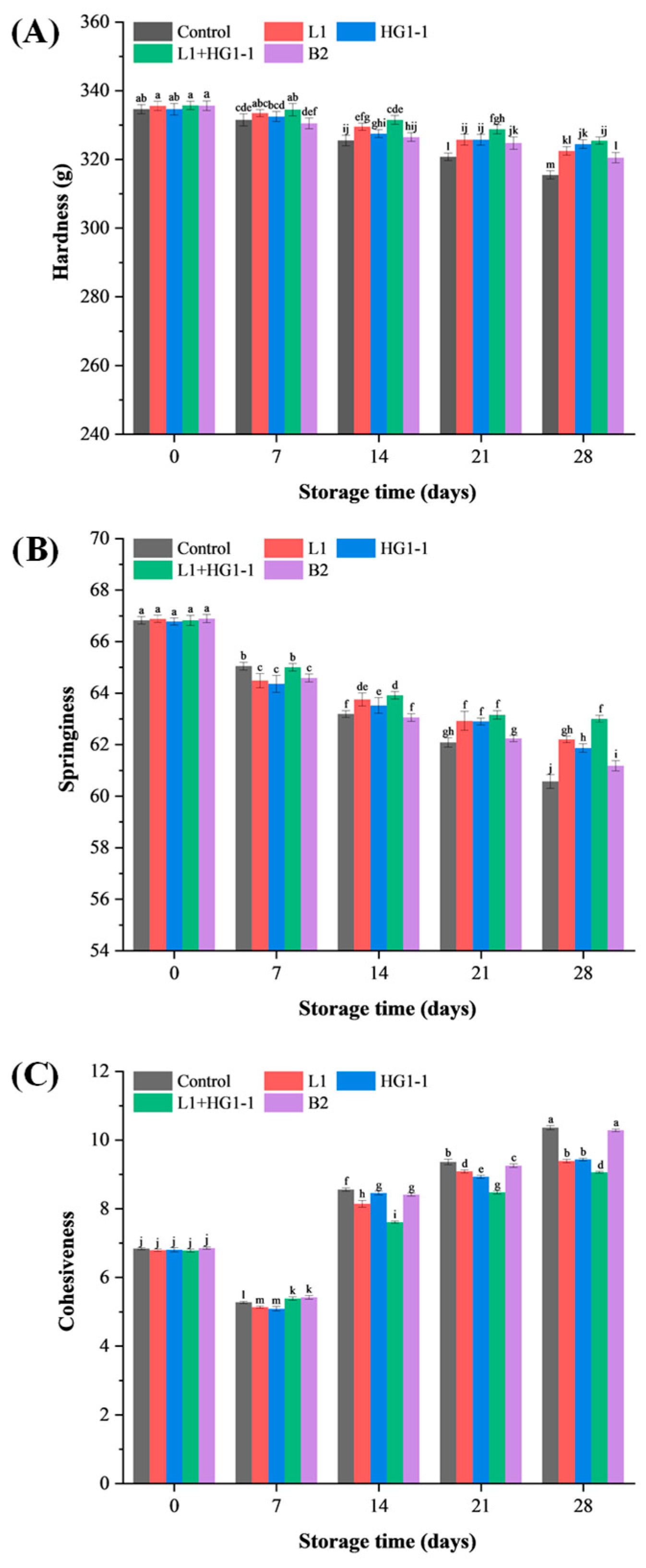

3.5. Textural Properties

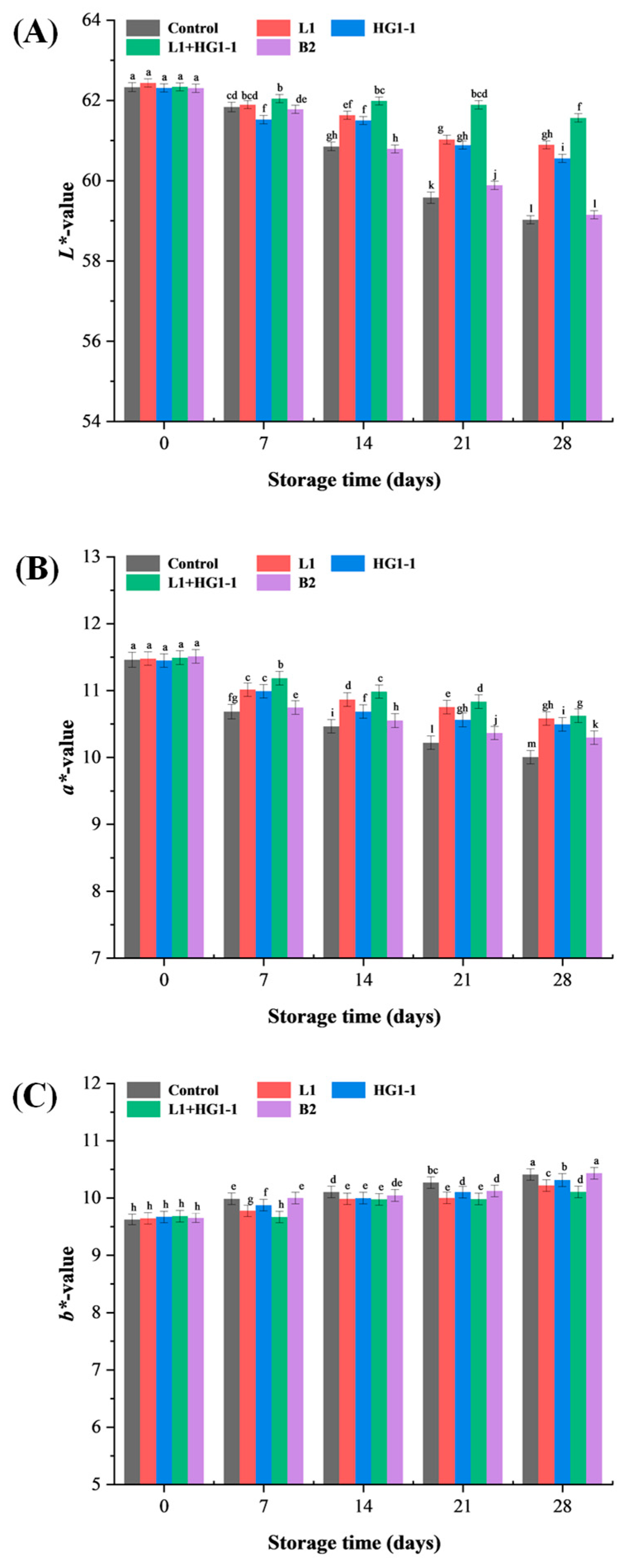

3.6. Color

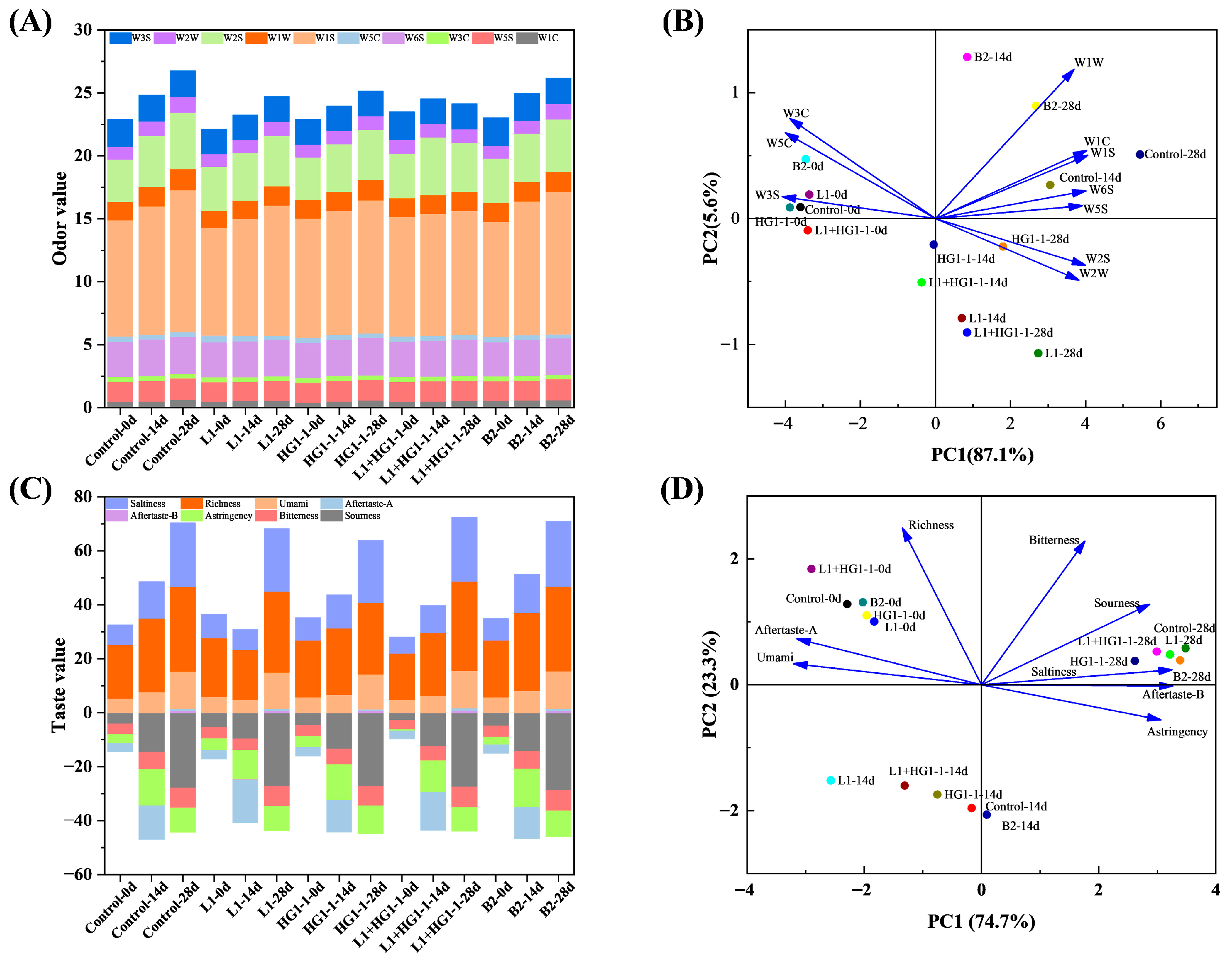

3.7. Electronic Nose

3.8. Electronic Tongue

3.9. Sensory Evaluation

3.10. General Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shao, L.; Bi, J.; Li, X.; Dai, R. Effects of vegetable oil and ethylcellulose on the oleogel properties and its application in Harbin red sausage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Pasquali, M.B.; Anjos, A.I.D.; Sarinho, A.M.; De Melo, E.D.; Andrade, R.; Batista, L.; Lima, J.; Diniz, Y.; Barros, A. Innovative and sustainable food preservation techniques: Enhancing food quality, safety, and environmental sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, A.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Functionality of ultra-high barrier metal oxide-coated polymer films for in-package, thermally sterilized food products. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, S.; Hashemi, S.M.B.; Abedi, E.; Amiri, M.J.; Conte, F.L. Bio-Preservation of meat and fermented meat products by lactic acid bacteria strains and their antibacterial metabolites. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Kong, B.; Chen, Q. Bioprotective potential of Latilactobacillus sakei and Latilactobacillus curvatus in smoked chicken legs with modified atmosphere packaging. Food Control 2024, 164, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.M.; Kaur, M.; Pillidge, C.J.; Torley, P.J. Effect of protective cultures on spoilage bacteria and the quality of vacuum-packaged lamb meat. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Cavalari, C.M.; Imazaki, P.H.; Pirard, B.; Lebrun, S.; Vanleyssem, R.; Gemmi, C.; Antoine, C.; Crevecoeur, S.; Daube, G.; Clinquart, A.; et al. Carnobacterium maltaromaticum as bioprotective culture against spoilage bacteria in ground meat and cooked ham. Meat Sci. 2024, 211, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.J.; Luo, H.T.; Kong, B.H.; Liu, Q.; Chen, C.G. Formation of red myoglobin derivatives and inhibition of spoilage bacteria in raw meat batters by lactic acid bacteria and Staphylococcus xylosus. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B.H. Selection and bacteriostatic properties of cryotolerant lactic acid bacteria with bioprotective potential. Food Sci. 2025, 46, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Gao, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Impact of pork collagen superfine powder on rheological and texture properties of Harbin red sausage. J. Texture Stud. 2017, 49, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhong, H.; Shi, H.; Yao, X.; Wang, W.; Tomasevic, I.; Zheng, J.; Sun, W. Sodium substitutes synergizing with dietary fiber: Effect on the textural, sensory, digestive, and storage properties of emulsified sausages. Food Chem. 2025, 147414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Yin, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Kong, B. The prediction of specific spoilage organisms in Harbin red sausage stored at room temperature by multivariate statistical analysis. Food Control 2020, 123, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Asiri, S.A.; Al-Dalali, S. Analysis of changes in flavor characteristics of Lipu taro pork at different stages of cooking based on GC-IMS, electronic nose, and electronic tongue. Food Chem. X 2025, 500, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11037:2011 ; Sensory Analysis — Guidelines for Sensory Assessment of the Colour of products. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Bassey, A.P.; Liu, P.P.; Chen, J.H.; Bako, H.K.; Boateng, E.F.; Ibeogu, H.I.; Ye, K.P.; Li, C.B.; Zhou, G.H. Antibacterial efficacy of phenyllactic acid against Pseudomonas lundensis and Brochothrix thermosphacta and its synergistic application on modified atmosphere/air-packaged fresh pork loins. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 2726-2016; Hygienic Standard for Cooked Meat Products. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Ștefan, G.; Predescu, C.N. Using the bioprotection culture for dry fermented salami-the control measure of Listeria monocytogenes growth. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2024, 67, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Casaburi, A.; di Martino, V.; Ferranti, P.; Picariello, L.; Villani, F. Technological properties and bacteriocins production by Lactobacillus curvatus 54M16 and its use as starter culture for fermented sausage manufacture. Food Control 2016, 59, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, I.; Slima, S.B.; Ktari, N.; Triki, M.; Abdehedi, R.; Abaza, W.; Moussa, H.; Abdeslam, A.; Salah, R.B. Incorporation of probiotic strain in raw minced beef meat: Study of textural modification, lipid and protein oxidation and color parameters during refrigerated storage. Meat Sci. 2019, 154, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Slima, S.; Ktari, N.; Trabelsi, I.; Triki, M.; Feki-Tounsi, M.; Moussa, H.; Makni, I.; Herrero, A.; Jiménez-Colmenero, F.; Perez, C.R.; et al. Effect of partial replacement of nitrite with a novel probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum TN8 on color, physico-chemical, texture and microbiological properties of beef sausages. LWT 2017, 86, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, C.; Messias, V.; Morgano, M.; Hayakawa, F.; Pollonio, M. Textural, microstructural and sensory properties of reduced sodium frankfurter sausages containing mechanically deboned poultry meat and blends of chloride salts. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, F.; Li, P.; Gu, Q. Antioxidant properties and molecular mechanisms of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ZJ316: A potential probiotic resource. LWT 2023, 187, 115269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İncili, G.K.; Akgöl, M.; Karatepe, P.; Üner, S.; Tekin, A.; Kanmaz, H.; Kaya, B.; Çalicioğlu, M.; Hayaloğlu, A.A. Quantification of bioactive metabolites derived from cell-free supernatant of P. acidilactici and screening their protective properties in frankfurters. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Li, D.; Niu, C.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. Antioxidant activity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from traditional Chinese fermented foods. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1914–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikou, P.; Ambrosiadis, I.; Georgantelis, D.; Koidis, P.; Georgakis, S.A. Effect of Lactobacillus-protective cultures with bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances’ producing ability on microbiological, chemical and sensory changes during storage of refrigerated vacuum-packaged sliced beef. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. Food stability determination by macro–micro region concept in the state diagram and by defining a critical temperature. J. Food Eng. 2009, 99, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Li, L.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, C. Novel insight into the formation and improvement mechanism of physical property in fermented tilapia sausage by cooperative fermentation of newly isolated lactic acid bacteria based on microbial contribution. Food Res. Int. 2024, 187, 114456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, J.Y.; Zhu, L.X.; Luo, X.; Mao, Y.W.; Hopkins, D.L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Dong, P.C. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life and bacterial community of roast duck meat. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Mittal, A.; Benjakul, S. Undesirable discoloration in edible fish muscle: Impact of indigenous pigments, chemical reactions, processing, and its prevention. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensor Name | Representative Material Species | Representative Material |

|---|---|---|

| W1C | Aromatic compounds | Sensitive to aromatic constituents, benzene |

| W5S | Broad range | Sensitive to nitrogen oxides |

| W3C | Aromatic | Sensitive to aroma, ammonia |

| W6S | Hydrogen | Sensitive to hydrides |

| W5C | Arom-aliph | Sensitive to short-chain alkane aromatic component |

| W1S | Broad-methane | Sensitive to methyl |

| W1W | Sulphur-organic | Sensitive to sulfides |

| W2S | Broad-alcohol | Sensitive to alcohols, aldehydes and ketones |

| W2W | Sulph-chlor | Sensitive to organic sulfides |

| W3S | Methane-aliph | Sensitive to long-chain alkanes |

| Storage Time | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | L1 | HG1-1 | L1 + HG1-1 | B2 | ||

| Moisture content (%) | 0 | 58.56 ± 0.01 b | 58.55 ± 0.01 b | 58.55 ± 0.01 b | 58.52 ± 0.01 bc | 58.49 ± 0.48 c |

| 7 | 58.40 ± 0.01 d | 58.48 ± 0.47 c | 58.49 ± 0.01 c | 58.50 ± 0.01 c | 58.41 ± 0.01 d | |

| 14 | 58.89 ± 0.03 a | 57.98 ± 0.01 e | 57.97 ± 0.24 e | 57.99 ± 0.07 e | 57.88 ± 0.02 f | |

| 21 | 57.85 ± 0.01 f | 57.86 ± 0.01 f | 57.85 ± 0.02 f | 57.86 ± 0.01 f | 57.84 ± 0.02 fg | |

| 28 | 57.80 ± 0.02 g | 57.82 ± 0.01 fg | 57.81 ± 0.01 fg | 57.83 ± 0.01 fg | 57.81 ± 0.01 fg | |

| Water activity (aw) | 0 | 0.99 ± 0.01 a | 0.98 ± 0.01 a | 0.99 ± 0.01 a | 0.98 ± 0.01 a | 0.98 ± 0.01 a |

| 7 | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 0.98 ± 0.01 a | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | |

| 14 | 0.96 ± 0.01 ab | 0.96 ± 0.01 ab | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | |

| 21 | 0.95 ± 0.01 ab | 0.96 ± 0.02 ab | 0.96 ± 0.01 ab | 0.96 ± 0.01 ab | 0.96 ± 0.01 ab | |

| 28 | 0.94 ± 0.01 b | 0.95 ± 0.01 ab | 0.95 ± 0.01 ab | 0.95 ± 0.01 ab | 0.93 ± 0.02 b | |

| Storage Time (Days) | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | L1 | HG1-1 | L1 + HG1-1 | B2 | ||

| Browning index | 0 | 29.73 ± 0.07 j | 29.73 ± 0.03 j | 29.81 ± 0.11 ij | 29.87 ± 0.16 hi | 29.85 ± 0.15 hi |

| 7 | 29.80 ± 0.11 ij | 29.73 ± 0.09 j | 30.09 ± 0.08 g | 29.64 ± 0.07 k | 29.92 ± 0.11 ghi | |

| 14 | 30.28 ± 0.06 fg | 30.10 ± 0.13 g | 29.99 ± 0.02 ghi | 30.04 ± 0.08 gh | 30.30 ± 0.05 fg | |

| 21 | 31.01 ± 0.14 c | 30.32 ± 0.07 fg | 30.37 ± 0.04 f | 29.93 ± 0.07 ghi | 30.72 ± 0.09 de | |

| 28 | 31.35 ± 0.17 b | 30.62 ± 0.04 e | 30.89 ± 0.09 cd | 30.10 ± 0.12 g | 31.68 ± 0.14 a | |

| Chroma | 0 | 14.96 ± 0.09 a | 14.99 ± 0.08 a | 14.98 ± 0.11 a | 15.02 ± 0.07 a | 15.02 ± 0.10 a |

| 7 | 14.62 ± 0.17 cde | 14.72 ± 0.11 abc | 14.77 ± 0.16 ab | 14.78 ± 0.09 ab | 14.68 ± 0.08 bcd | |

| 14 | 14.54 ± 0.13 cde | 14.75 ± 0.08 abc | 14.63 ± 0.07 cde | 14.84 ± 0.16 ab | 14.57 ± 0.12 cde | |

| 21 | 14.48 ± 0.12 de | 14.68 ± 0.08 bcd | 14.61 ± 0.04 cde | 14.73 ± 0.13 abc | 14.49 ± 0.09 de | |

| 28 | 14.43 ± 0.08 e | 14.71 ± 0.15 bcd | 14.71 ± 0.15 bcd | 14.66 ± 0.06 bcd | 14.65 ± 0.13 bcd | |

| Total color change (ΔE) | 0 | - | 0.11 ± 0.03 l | 0.05 ± 0.03 l | 0.06 ± 0.02 l | 0.06 ± 0.03 l |

| 7 | 0.99 ± 0.13 i | 0.65 ± 0.09 j | 0.97 ± 0.03 i | 0.40 ± 0.05 k | 0.98 ± 0.05 i | |

| 14 | 1.85 ± 0.05 f | 0.99 ± 0.10 i | 1.20 ± 0.07 h | 0.69 ± 0.07 j | 1.84 ± 0.09 f | |

| 21 | 3.09 ± 0.06 c | 1.54 ± 0.08 g | 1.77 ± 0.06 f | 0.85 ± 0.13 ij | 2.73 ± 0.13 d | |

| 28 | 3.70 ± 0.14 a | 1.79 ± 0.09 f | 2.14 ± 0.16 e | 1.23 ± 0.05 h | 3.49 ± 0.11 b | |

| Sensory Attribute | Storage Time (Days) | Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | L1 | HG1-1 | L1 + HG1-1 | B2 | ||

| Color | 0 | 6.43 ± 0.24 a | 6.41 ± 0.25 a | 6.40 ± 0.26 a | 6.44 ± 0.27 a | 6.41 ± 0.28 a |

| 14 | 3.80 ± 0.31 c | 3.90 ± 0.21 bc | 3.92 ± 0.23 bc | 4.08 ± 0.27 b | 3.82 ± 0.21 c | |

| 28 | 2.98 ± 0.32 f | 3.56 ± 0.28 de | 3.50 ± 0.31 de | 3.66 ± 0.28 d | 3.41 ± 0.31 e | |

| Hardness | 0 | 6.21 ± 0.21 a | 6.24 ± 0.32 a | 6.23 ± 0.24 a | 6.25 ± 0.28 a | 6.24 ± 0.24 a |

| 14 | 5.75 ± 0.31 cd | 5.92 ± 0.27 b | 5.95 ± 0.25 b | 5.92 ± 0.26 b | 5.81 ± 0.27 bc | |

| 28 | 4.95 ± 0.33 g | 5.58 ± 0.35 e | 5.56 ± 0.34 e | 5.68 ± 0.32 de | 5.27 ± 0.28 f | |

| Odor | 0 | 6.49 ± 0.22 a | 6.51 ± 0.21 a | 6.50 ± 0.29 a | 6.48 ± 0.25 a | 6.49 ± 0.25 a |

| 14 | 3.86 ± 0.27 c | 4.08 ± 0.21 b | 4.05 ± 0.28 bc | 4.10 ± 0.27 b | 3.90 ± 0.24 c | |

| 28 | 3.06 ± 0.22 f | 3.22 ± 0.31 de | 3.28 ± 0.21 de | 3.36 ± 0.25 d | 3.16 ± 0.24 ef | |

| Overall acceptability | 0 | 6.53 ± 0.29 a | 6.55 ± 0.27 a | 6.55 ± 0.26 a | 6.54 ± 0.25 a | 6.52 ± 0.31 a |

| 14 | 3.78 ± 0.31 de | 4.10 ± 0.21 bc | 4.02 ± 0.31 bcd | 4.20 ± 0.31 b | 4.06 ± 0.28 bc | |

| 28 | 3.02 ± 0.23 f | 3.86 ± 0.32 d | 3.80 ± 0.31 d | 3.95 ± 0.32 cd | 3.64 ± 0.34 e | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B. Bioprotective Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici L1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HG1-1 in Harbin Red Sausage Under Vacuum Packaging. Foods 2025, 14, 4293. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244293

Wang Q, Zhang K, Chen Q, Liu H, Zhang C, Liu Q, Kong B. Bioprotective Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici L1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HG1-1 in Harbin Red Sausage Under Vacuum Packaging. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4293. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244293

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiang, Kaida Zhang, Qian Chen, Haotian Liu, Chao Zhang, Qian Liu, and Baohua Kong. 2025. "Bioprotective Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici L1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HG1-1 in Harbin Red Sausage Under Vacuum Packaging" Foods 14, no. 24: 4293. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244293

APA StyleWang, Q., Zhang, K., Chen, Q., Liu, H., Zhang, C., Liu, Q., & Kong, B. (2025). Bioprotective Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici L1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HG1-1 in Harbin Red Sausage Under Vacuum Packaging. Foods, 14(24), 4293. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244293