Assessment of Bacterial Communities in Raw Milk Cheeses from Central Poland Using Culture-Based Methods and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Culture-Based Methods

2.3. DNA Isolation

2.4. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Culture-Based Methods

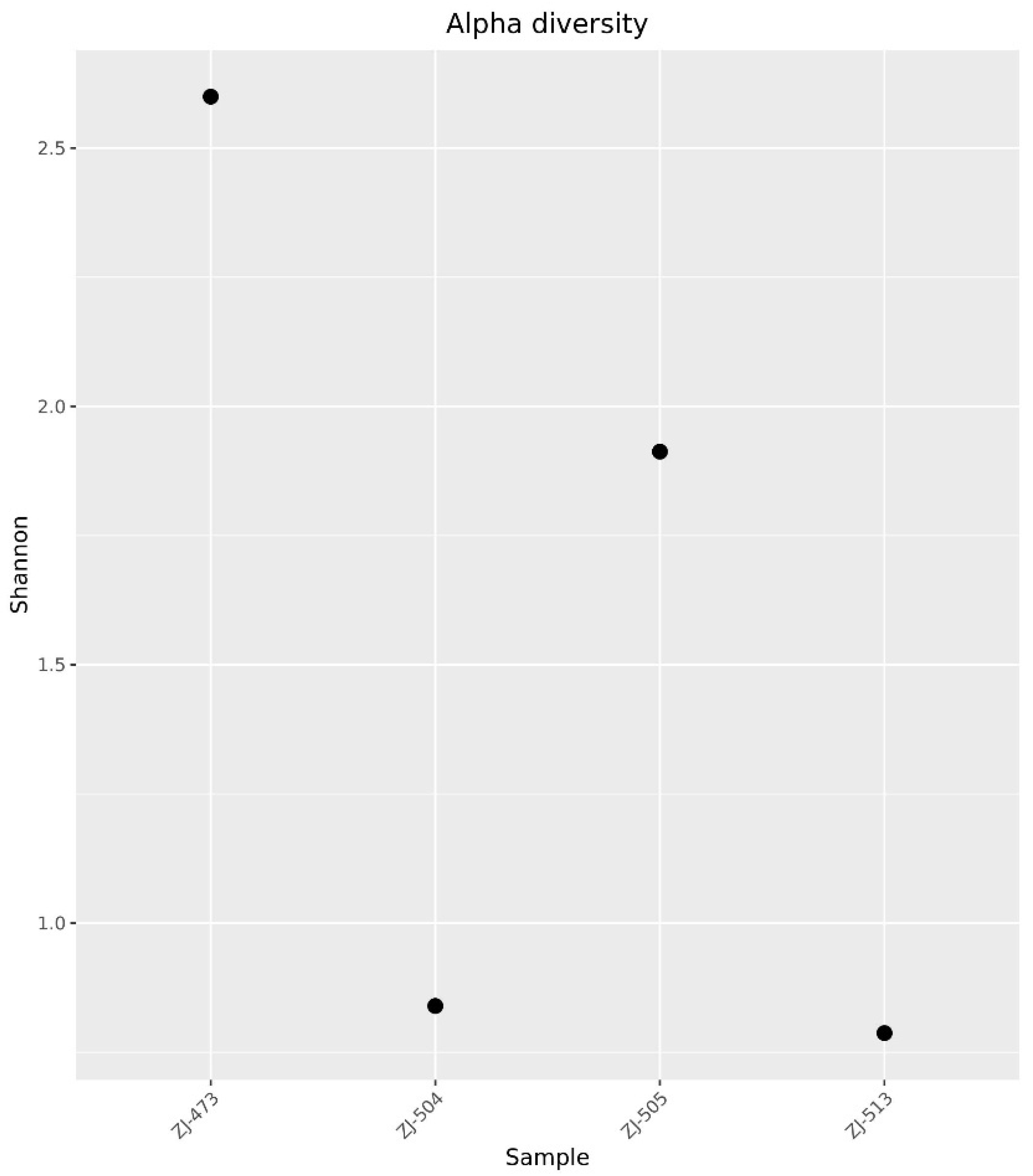

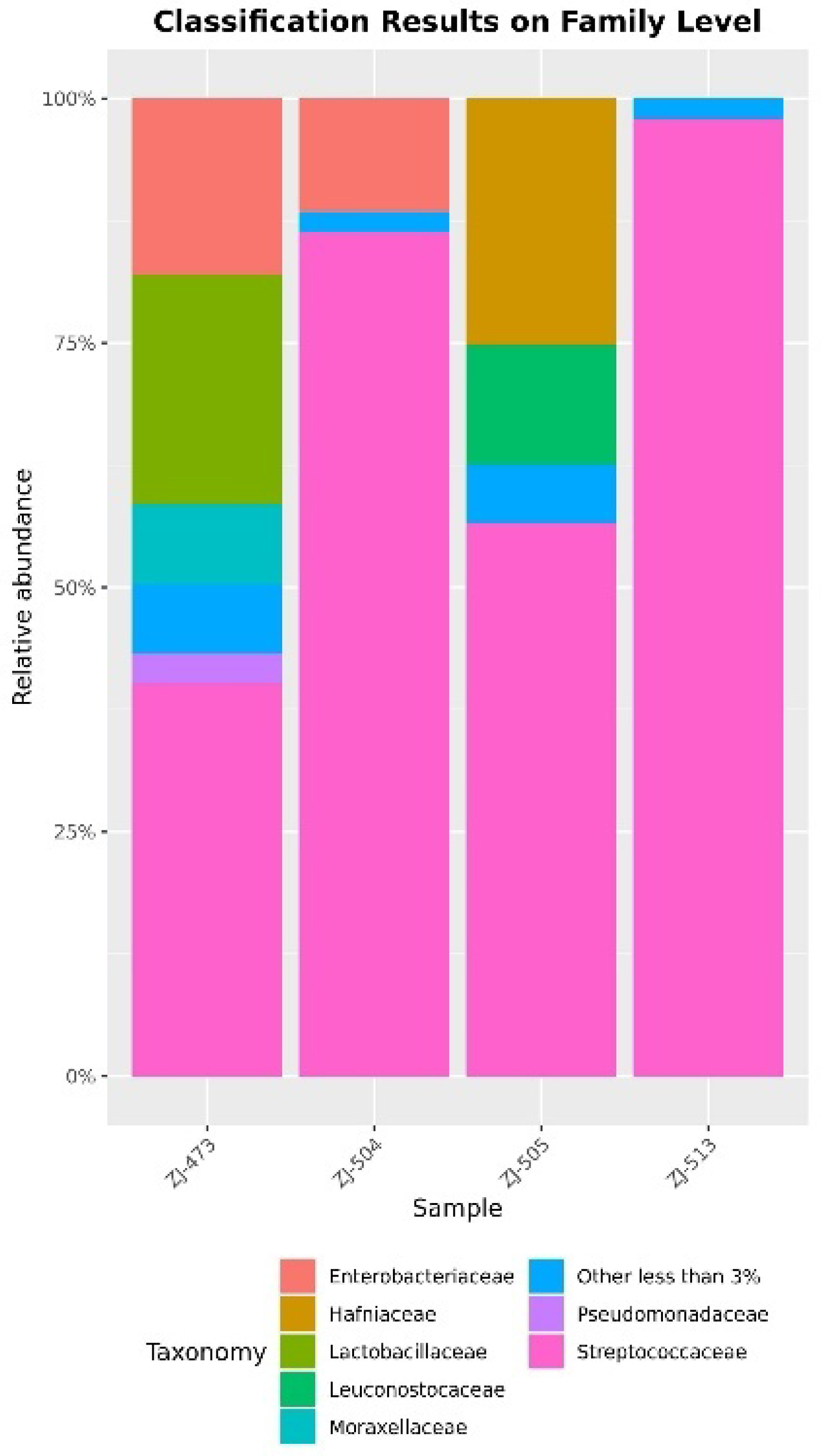

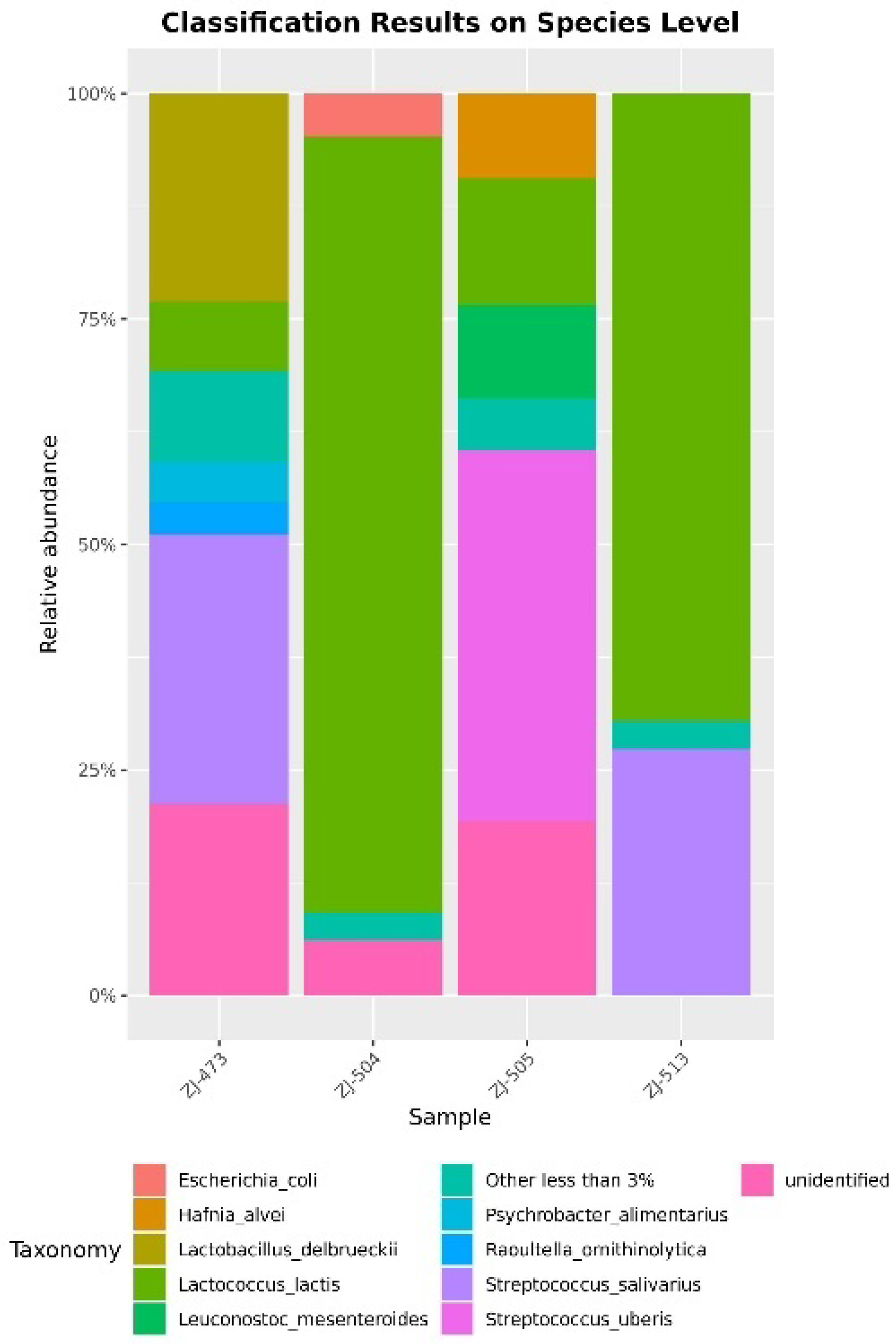

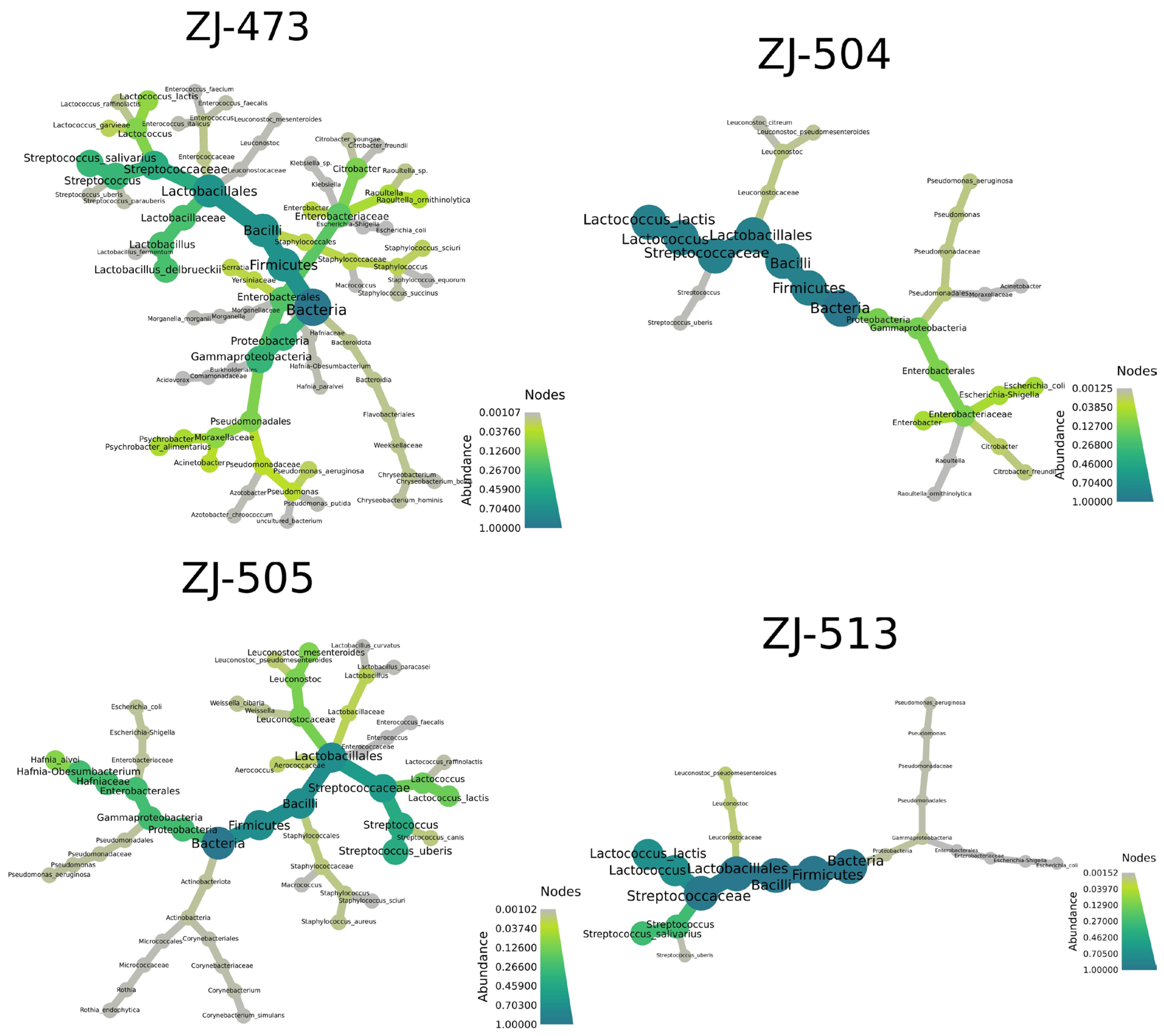

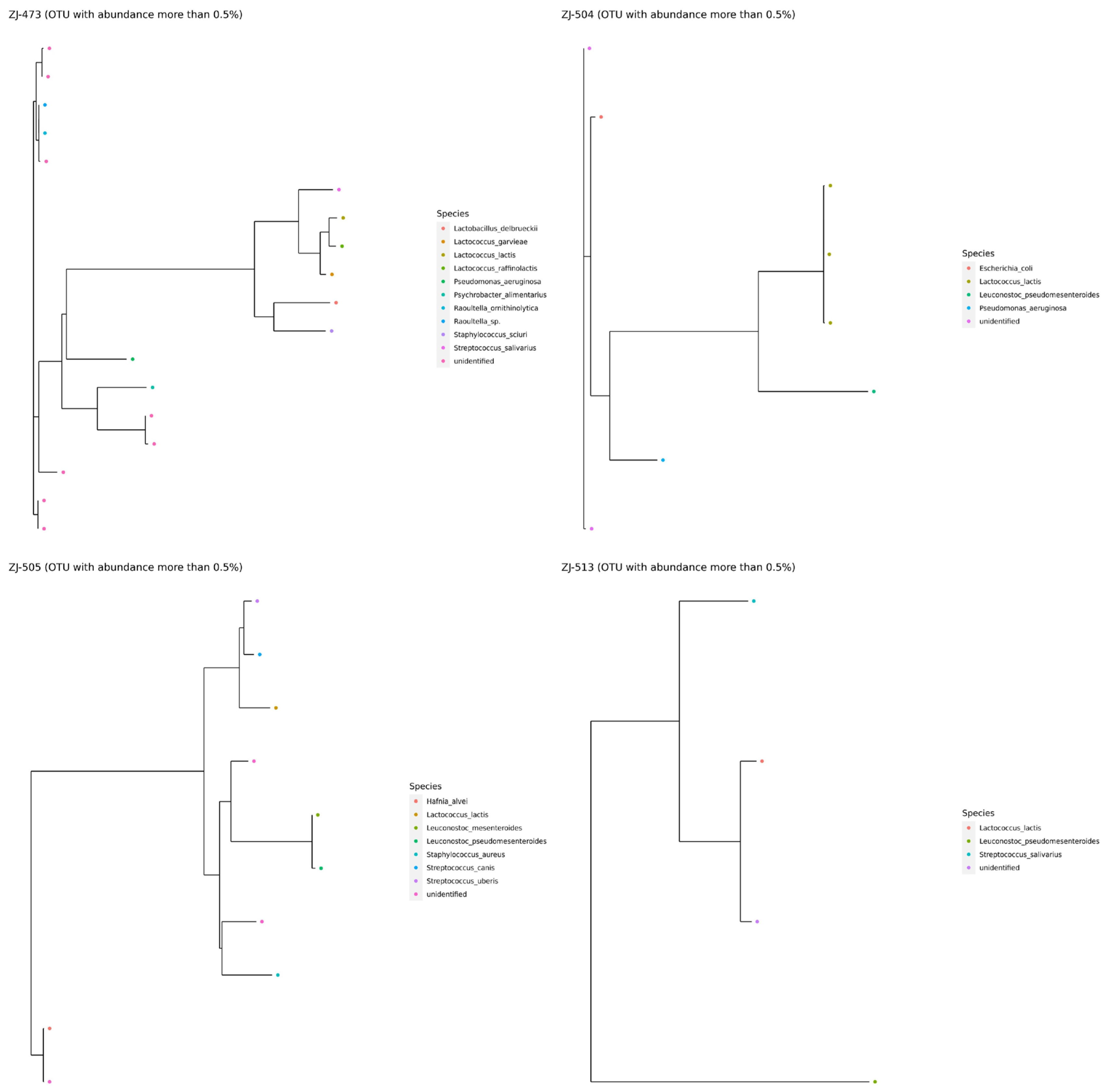

3.2. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Burgos, M.; Moreno-Fernández, J.; Alférez, M.J.M.; Díaz-Castro, J.; López-Aliaga, I. New Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health Relevance. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, T.; Nunes, F.; Veiga, J.; Mata, F.; Alexandraki, M.; Dimitriou, L.; Meleti, E.; Manouras, A.; Malissiova, E. Trends in Organic Food Choices and Consumption: Assessing the Purchasing Behaviour of Consumers in Greece. Foods 2025, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoszewska, A.; Maćkiw, E.; Kowalska, J.; Patoleta, M.; Ławrynowicz-Paciorek, M.; Postupolski, J. Microbiological Risks of Traditional Raw Cow’s Milk Cheese (Koryciński Cheeses). Foods 2024, 13, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, C.-R.; Bartodziejska, B.; Gajewska, M.; Szosland-Fałtyn, A. Microbiological Quality and Safety of Traditional Raw Milk Cheeses Manufactured on a Small Scale by Polish Dairy Farms. Foods 2022, 11, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2022 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Lee, S.; Choi, K.-H. Microbial Benefits and Risks of Raw Milk Cheese. Food Control 2016, 63, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Guide for Good Hygiene Practices in the Production of Artisanal Cheese and Dairy Products. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-12/biosafety_fh_guidance_artisanal-cheese-and-dairy-products_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Tavaria, F.K.; Dos Santos, M.T.P.G.; Alvarenga, N.; Pintado, M.M. A Review on Microbiological and Technological Aspects of Serpa PDO Cheese: An Ovine Raw Milk Cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 100, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Raw-Milk Cheeses: From Starter Cultures to Probiotic Functions. Foods 2022, 11, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros Carvalho, M.; De Fariña, L.O.; Strongin, D.; Ferreira, C.L.L.F.; Lindner, J.D.D. Traditional Colonial-Type Cheese from the South of Brazil: A Case to Support the New Brazilian Laws for Artisanal Cheese Production from Raw Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 9711–9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, H.; Alizadeh Behbahani, B.; Falah, F. Safety, Probiotic Properties, Antimicrobial Activity, and Technological Performance of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Iranian Raw Milk Cheeses. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4094–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshidian, N.; Khanniri, E.; Koushki, M.R.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Yousefi, M. An Overview of Antimicrobial Activity of Lysozyme and Its Functionality in Cheese. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 833618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandi, S.; Silvetti, T.; Miranda Lopez, J.M.; Brasca, M. Antimicrobial Activity, Antibiotic Resistance and the Safety of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Raw Milk Valtellina Casera Cheese. J. Food Saf. 2015, 35, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vataščinová, T.; Pipová, M.; Fraqueza, M.J.R.; Maľa, P.; Dudriková, E.; Drážovská, M.; Lauková, A. Short Communication: Antimicrobial Potential of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Slovak Raw Sheep Milk Cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 6900–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisana, C.; Caccamo, M.; Barbera, M.; Marino, G.; Serio, G.; Franciosi, E.; Settanni, L.; Gaglio, R.; Caggia, C. Comprehensive Characterization of the Microbiological and Quality Attributes of Traditional Sicilian Canestrato Fresco Cheese. Foods 2025, 14, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neviani, E.; Gatti, M.; Gardini, F.; Levante, A. Microbiota of Cheese Ecosystems: A Perspective on Cheesemaking. Foods 2025, 14, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Albuquerque, T.M.N.C.; Campos, G.Z.; d’Ovidio, L.; Pinto, U.M.; Sobral, P.J.D.A.; Galvão, J.A. Unveiling Safety Concerns in Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses: A Call for Enhanced Ripening Protocols and Microbiological Assessments. Foods 2024, 13, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luziatelli, F.; Abou Jaoudé, R.; Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Ruzzi, M. Microbial Evolution in Artisanal Pecorino-Like Cheeses Produced from Two Farms Managing Two Different Breeds of Sheep (Comisana and Lacaune). Foods 2024, 13, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschard, J.S.; Schuppler, M. The Microbial Diversity on the Surface of Smear-Ripened Cheeses and Its Impact on Cheese Quality and Safety. Foods 2024, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4833-1:2013-12+A1:2022-06; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms Part 1: Colony Count at 30 °C by the Pour Plate Technique. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 15214:2002; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Mesophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria—Colony-Count Technique at 30 Degrees C. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ISO 7954:1999; Microbiology—General Guidance for Enumeration of Yeasts and Moulds—Colony Count Technique at 25 Degrees C. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- ISO 21528-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae Part 2: Colony-Count Technique. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 6888-2:2022-03; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species)—Part 2: Method Using Rabbit Plasma Fibrinogen Agar Medium. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 6579-1:2017/A1:2020-09; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 11290-1:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria Monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. Part 1: Detection Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuyama, J. phyloseqGraphTest: Graph-Based Permutation Tests for Microbiome Data 2018, 0.1.1. Available online: https://jfukuyama.r-universe.dev/phyloseqGraphTest (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2001, 2.7-2. Available online: https://vegandevs.r-universe.dev/vegan (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; Van Den Brand, T. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics 2007, 4.0.0. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Warnes, G.R.; Bolker, B.; Bonebakker, L.; Gentleman, R.; Huber, W.; Liaw, A.; Lumley, T.; Maechler, M.; Magnusson, A.; Moeller, S.; et al. Gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data 2005, 3.2.0. Available online: https://talgalili.r-universe.dev/gplots (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Sievert, C.; Parmer, C.; Hocking, T.; Chamberlain, S.; Ram, K.; Corvellec, M.; Despouy, P. Plotly: Create Interactive Web Graphics via “Plotly.Js” 2015, 4.11.0. Available online: https://plotly.r-universe.dev/plotly (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Galili, T.; O’Callaghan, A. Heatmaply: Interactive Cluster Heat Maps Using “plotly” and “Ggplot2” 2016, 1.6.0. Available online: https://talgalili.r-universe.dev/heatmaply (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Canales, R.A.; Wilson, A.M.; Pearce-Walker, J.I.; Verhougstraete, M.P.; Reynolds, K.A. Methods for Handling Left-Censored Data in Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01203-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Arcella, D.; Gómez Ruiz, J.A. Use of Cut-off Values on the Limits of Quantification Reported in Datasets Used to Estimate Dietary Exposure to Chemical Contaminants. EFSA J. 2018, 15, 1452E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.; Lee, S.C.; Park, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, H. Statistical Methods for Handling Nondetected Results in Food Chemical Monitoring Data to Improve Food Risk Assessments. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5223–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the “Tidyverse” 2016, 2.0.0. Available online: https://tidyverse.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Kassambara, A. Rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests 2019, 0.7.3. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/rstatix/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Mangiafico, S. Rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation 2016, 2.5.0. Available online: https://salvatoremangiafico.r-universe.dev/rcompanion (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Henry, L. Purrr: Functional Programming Tools 2015, 1.1.0. Available online: https://tidyverse.r-universe.dev/purrr (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Merchán, A.V.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Benito, M.J.; Vázquez Hernández, M.; Cabañas, C.M.; Román, Á.C. Metabarcoding Analysis Reveals a Differential Bacterial Community Profile Associated with ‘Torta Del Casar’ and ‘Queso de La Serena’ PDO Cheeses. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Bardelli, T.; Rossetti, L.; Nazzicari, N.; Carminati, D.; Galli, A.; Giraffa, G. Evaluation of Bacterial Communities of Grana Padano Cheese by DNA Metabarcoding and DNA Fingerprinting Analysis. Food Microbiol. 2021, 93, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation, (EC) Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance). 2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2005/2073/oj/eng (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Indio, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U.; Oliveri, C.; Lucchi, A.; Valero, A.; Achemchem, F.; Manfreda, G.; Savini, F.; Serraino, A.; De Cesare, A. Comparative Analysis of the Microbiome Composition of Artisanal Cheeses Produced in the Mediterranean Area. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 12818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saak, C.C.; Pierce, E.C.; Dinh, C.B.; Portik, D.; Hall, R.; Ashby, M.; Dutton, R.J. Longitudinal, Multi-Platform Metagenomics Yields a High-Quality Genomic Catalog and Guides an In Vitro Model for Cheese Communities. Msystems 2023, 8, e00701-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Valentino, V.; Yap, M.; Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Barcenilla, C.; Carlino, N.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Quijada, N.M.; Calvete-Torre, I.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; et al. Microbiome Mapping in Dairy Industry Reveals New Species and Genes for Probiotic and Bioprotective Activities. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, E.; Zotta, T.; Ricciardi, A. Microbial Association Networks in Cheese: A Meta-Analysis. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2021.2007. [Google Scholar]

| Analysis | Cheese Symbol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZJ-473 | ZJ-504 | ZJ-505 | ZJ-513 | |

| TCM [log CFU g−1] | 7.08 [7.02–7.15] ab | 5.6 [5.56–5.61] a | 7.28 [7.16–7.33] ab | 8.58 [8.57–8.61] b |

| ENT [log CFU g−1] | 5.98 [5.97–6.03] a | 2.59 [2.50–2.64] b | 5.83 [5.77–5.86] ab | 5.08 [5.04–5.10] ab |

| CPS [log CFU g−1] | 0.50 [0.50–0.50] a | 3.08 [3.03–3.13] ab | 6.04 [6.01–6.14] b | 0.50 [0.50–0.50] a |

| LAB [log CFU g−1] | 6.23 [6.14–6.29] ab | 4.49 [4.47–4.54] a | 6.98 [6.97–7.05] ab | 8.82 [8.81–8.84] b |

| Y [log CFU g−1] | 5.43 [5.39–5.47] ab | 3.40 [3.33–3.42] ab | 6.81 [6.78–6.83] a | 2.32 [2.29–2.34] b |

| M [log CFU g−1] | 0.50 [0.50–0.50] a | 0.50 [0.50–0.50] a | 3.08 [3.03–3.52] b | 0.50 [0.50–0.50] a |

| SALM | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| LIST | nd | nd | nd | nd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maciejewska, N.; Szosland-Fałtyn, A.; Bartodziejska, B. Assessment of Bacterial Communities in Raw Milk Cheeses from Central Poland Using Culture-Based Methods and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Foods 2025, 14, 4288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244288

Maciejewska N, Szosland-Fałtyn A, Bartodziejska B. Assessment of Bacterial Communities in Raw Milk Cheeses from Central Poland Using Culture-Based Methods and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244288

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaciejewska, Nikola, Anna Szosland-Fałtyn, and Beata Bartodziejska. 2025. "Assessment of Bacterial Communities in Raw Milk Cheeses from Central Poland Using Culture-Based Methods and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing" Foods 14, no. 24: 4288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244288

APA StyleMaciejewska, N., Szosland-Fałtyn, A., & Bartodziejska, B. (2025). Assessment of Bacterial Communities in Raw Milk Cheeses from Central Poland Using Culture-Based Methods and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Foods, 14(24), 4288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244288